Chinese people in Germany

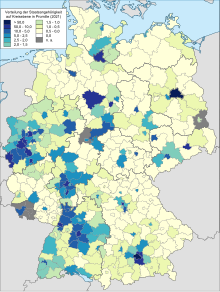

Distribution of Chinese citizens in Germany (2021) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 212,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Berlin,[2] Frankfurt am Main, Ruhr Area, Munich, Hamburg,Braunschweig,Nuremberg,Hanover,Leipzig | |

| Languages | |

| Numerous varieties of Chinese (predominantly Mandarin, Hokkien, Wu, and Cantonese), German;[2] English not widely spoken[3] | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism,[4] Christianity, Conscious Atheism, Non-adherence | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Overseas Chinese |

| Chinese German | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 德國華人 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 德国华人 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 德國華僑 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 德国华侨 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| German name | |||||||||||||

| German | Chinesen in Deutschland Deutsch-Chinesen chinesische Deutsche | ||||||||||||

Chinese people in Germany form one of the smaller groups of overseas Chinese in Europe, consisting mainly of Chinese expatriates living in Germany and German citizens of Chinese descent.[5] The German Chinese community is growing rapidly and, as of 2016, was estimated to be around 212,000 by the Federal Institute for Population Research.[1] In comparison to that, the Taiwanese OCAC had estimated there were 110,000 people of Chinese descent living in Germany in 2008.[6]

Migration history

[edit]19th century to World War I

[edit]Though not well known even to local Chinese communities which formed later, the earliest Chinese in Germany, Feng Yaxing and Feng Yaxue, both from Guangdong, first came to Berlin in 1822 by way of London.[7] Cantonese-speaking seafarers, employed on German steamships as stokers, coal trimmers, and lubricators, began showing up in ports such as Hamburg and Bremen around 1870.[5] Forty-three lived in Hamburg by 1890, 207 persons in 1910, mostly former seamen.[8][9] Hamburg boasted the only Chinatown in Germany (actually only one or two streets). In the 1890s, many shipping companies began to replace their white crews with much cheaper Chinese (also Indian and African) labour, esp. for the extremely tiresome work in the engine rooms (often at more than 40 °C temperature). Among the 47,780 registered members of the Seeberufsgenossenschaft (roughly Seamen's Insurance Society) around 1900, more than 3,000 were Chinese.[10] The labour unions and the Social Democratic Party strongly disapproved of their presence; their 1898 boycott of Chinese crews, motivated by racial concerns, resulted in the passage of a law by the Reichstag on 30 October 1898 stating that Chinese could not be employed on shipping routes to Australia, and could be employed on routes to China and Japan only in positions that whites would not take because they were detrimental to health. Mass layoffs of Chinese seafarers resulted.[11]

Since the 1880s, there were debates about employing Chinese "coolies" as farm workers in East Elbia, i.e. Prussia's extensive eastern provinces characterised by large agricultural estates. Usually Eastern Europeans, esp. Poles, provided the necessary labour there but German emigration from these areas, higher Polish fertility and an increasing political mobilisation of the Polish minority stoked anxieties about their "infiltration", esp. through mixing with the local Germans. Some observers saw a solution in introducing a totally alien ethnic element which would be easier to segregate (e.g. Friedrich Syrup, later director of the Reich Labour Bureau in late Weimar and Nazi times). The Chinese were seen as especially resistant to cultural assimilation, on the basis of experiences in Australia and North America. Estate owners therefore pushed for their immigration or at least a consideration of such proposals, e.g. in Pomerania in 1889. Public and administrative opinion was "almost totally negative", due to unfavorable opinions in the English-speaking world at the time (cf. Yellow Peril) and fears of racial miscegenation. Nevertheless, the Prussian Foreign Office made inquiries, e.g. about Chinese workers in the Netherlands East Indies. After receiving a comprehensive report from Beijing in 1895, the Office concluded on the grounds of transport and wage costs that such plans were not promising success. A new wave of proposals came in 1906/07 but failed similarly after a statement by German colonial authorities from Kiautschou, China.[12]

Aside from seafarers, students formed the other major group of Chinese living in Germany at the turn of the century. In 1904, at the time of Sun Yat-sen's visit to Germany and other Western European countries, more than twenty joined the anti-Qing Chinese United League he organised in Berlin.[13] There were also groups of travelling entertainers from Shandong, with a smaller proportion from Zhejiang, who came to Germany overland, travelling through Russia and Poland to reach Berlin.[14]

Chinese workers were also employed in the German overseas colonies, similar to British and French practices. Until 1894, about 1,000 "coolies" were recruited for German East Africa but corporal punishment and the tropical climate were so severe the British colonial authorities in Singapore and Hong Kong did not permit further emigration. Another focus of migration were the Pacific colonies where Chinese workers were deemed indispensable for the lucrative plantations. In 1914, there were 1,377 Chinese in German New Guinea (against 1,137 whites) and 2,184 Chinese on Samoa (against 373 Germans). Tensions with the Chinese government about the brutal treatment of workers never fully ceased. The Chinese were never given the same rights as whites, but were treated similar to the natives due to their supposedly "inferior level of culture". There were, however, also efforts to prevent mixing with the natives.[15]

Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany

[edit]Chinese formed the fourth largest group of foreign students in Germany by the mid-1920s. Many became involved with radical politics, especially in Berlin; they joined the Communist Party of Germany, and were responsible for setting up its Chinese-language section, the Zirkel für chinesische Sprache.[16] Chinese communists such as Zhu De and Liao Chengzhi remained active in the late 1920s and early 1930s; Liao succeeded in organising a strike among Chinese sailors in Hamburg to prevent the shipment of armaments to China.[17]

The Nazis, who came to power in 1933, did not classify the Chinese as racially inferior to the Japanese, but because so much of the Chinese community had ties to leftist movements, they fell under increased official scrutiny regardless, and many left the country, either heading to Spain to fight in the Civil War that was raging there, or returning to China.[18] As late as 1935, the Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission's statistics showed 1,800 Chinese still living in Germany; more than one thousand of these were students in Berlin, while another few hundred were seafarers based in Hamburg.[13] However, this number shrank to 1,138 by 1939.[19]

After the Chinese government declared war on Nazi Germany following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Gestapo launched mass arrests of Chinese Germans and Chinese nationals across Germany,[20] In 1942, the 323 who still lived in Berlin were all arrested and sent to the Langer Morgen work camp.[21] Many were tortured or worked to death by the Gestapo.[22] By the end of World War II, every Chinese restaurant in Hamburg had closed.[23]

Division and reunification of Germany

[edit]After the war, the Chinese government sent officials to organise repatriation for the few hundred Chinese who remained in Germany. Of the 148 from Hamburg, only one, a survivor of Langer Morgen, declined repatriation; he opened the Peace Restaurant, Hamburg's first post-war Chinese restaurant. However, those who departed were soon replaced by new immigrants. In 1947, there were 180 Chinese in Berlin's western sector, and another 67 in the eastern sector; a year later, those numbers had grown to 275 and 72, respectively. With the establishment of the People's Republic of China and its subsequent recognition by East Germany, many traders moved to East Berlin, expecting that there they would be better protected there by their homeland's new government.[24] West Germany did not formally recognise the Republic of China on Taiwan (ROC) and did not establish relations with the People's Republic of China PRC until 1972.[24]

Migration of ethnic Chinese to West Germany in the 1960s and 1970s was drawn primarily from the communities of British Chinese and Chinese in the Netherlands.[25] Other re-migrants came from Italy, Portugal, and Spain.[26] German authorities generally preferred not to issue residence permits to PRC nationals.[25] Regardless, numbers of PRC and ROC nationals in Germany continued to increase, with 477 from the former and 1,916 from the later by 1967.[27] In addition to individual migrants, both the PRC and the ROC provided workers with specific skills to Germany under bilateral agreements. The ROC sent a total of 300 nurses in the 1960s and 1970s.[24] In the case of the PRC, the agreement signed in 1986 for China to provide 90,000 industrial trainees to East Germany was barely implemented by the time the Berlin Wall fell; out of the 90,000 whom the Chinese agreed to send, barely 1,000 went, and all but 40 had gone back home by December 1990.[24] Immigration from the PRC to West Germany was much larger than that to East Germany; in 1983, the number of PRC nationals living there surpassed the number of ROC nationals, and by 1985 had grown to 6,178, versus only 3,993 ROC nationals. By just eight years later, their numbers had more than quintupled; 31,451 PRC nationals lived in Germany, as opposed to only 5,626 ROC nationals.[27] There were also tens of thousands of ethnic Chinese not included in either of the above categories, primarily Vietnamese people of Chinese descent and Hong Kong residents with British National (Overseas) passports.[28]

In East Germany, there were slightly fewer than 1,000 Chinese "contract workers" (Vertragsarbeiter) from the People's Republic in the late 1980s. The SED leadership signalled its support to the CCP's handling of the Tiananmen massacre in the summer of 1989. In return, when increasing emigration deepened the GDR's socio-economic crisis in autumn 1989, the PRC Minister of Housing Lin Hanxiong offered "to provide the GDR with the number and qualification of workers as desired." As this proposal came only days before the collapse of the East German regime however, it was quickly made obsolete by the rapid political changes.[29]

Socioeconomics

[edit]Employment

[edit]Food service has remained a dominant means of making a livelihood in the Chinese community. For example, in Tilburg, the restaurant industry employs roughly 60% of the Chinese population.[30] Even students in Germany who earned doctorates in the sciences have ended up starting restaurants or catering services, rather than engaging in any work related to their studies.[2]

In Berlin, many Chinese restaurants can be found in Walther Schreiber Platz, as well as along Albrechtstrasse and Grunewaldstrasse.[23] The travel agency business is another one in which intra-ethnic networks have proven valuable; Chinese travel agencies in Germany sell primarily to other Chinese making return trips to their country of origin. Estimates of the number of Chinese travel agencies in Germany range between thirty-five and a few hundred.[31] In contrast, marine-based industries no longer employ a very large proportion of the Chinese community; by 1986, Chinese formed no more than 2%, or 110 individuals, of the foreign workforce on German vessels.[2]

Education

[edit]Students also continue to form a large portion of Germany's Chinese population. In comments to German chancellor Helmut Kohl in 1987, Deng Xiaoping stressed his desire to diversify the destinations of Chinese students going overseas, aiming to send a larger proportion to Europe and a smaller proportion to the United States.[32] By 2000, Chinese formed the largest group of foreign students in German universities, with 10,000 in 2002 and 27,000 in 2007.[33][34] Schools aimed at the children of Germany's Chinese residents have been set up as well; as early as 1998, there were two Chinese schools in Berlin, one run by the city government, and the other privately established by a group of parents.[23] Stuttgart boasts one such school as well; however, Chinese graduate students who intend to return to China after graduation typically choose instead to home-school their children in accordance with China's national curriculum, to aid their re-integration into the public school system.[35]

Second-generation Chinese students were more likely to attend a Gymnasium (college preparatory school) than their ethnic German counterparts.[36]

Population

[edit]The German Chinese community has seen a rapid growth in recent years. In 2016, there were 201,000 nationals of the People's Republic of China living in Germany,[37] a 35% increase over 2013. The number of Taiwanese citizens living in the country stood at 5,885 (as of 2013).[38] In addition, there is a large number of Chinese people who naturalized as German citizens or who are natively born in the country. Between 2004 and 2007 alone, 4,213 PRC nationals naturalised as German citizens.[39] In addition to that, the Chinese community in Germany also consists of tens of thousands[2] of ethnic Chinese from countries such as Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia.

The growth of the Chinese community can be exemplified by the city of Duisburg. In 2010, there were 568 citizens of the PRC in Duisburg; in 2018, the population was approximately 1,136.[40] The number does not include naturalized German Chinese.

| Number of Chinese in larger cities | |||||||||

| # | City | People | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Berlin | 13,293 | |||||||

| 2. | Munich | 9,240 | |||||||

| 3. | Hamburg | 6,235 | |||||||

| 4. | Frankfurt | 4,632 | |||||||

| 5. | Düsseldorf | 4,175 | |||||||

| 6. | Stuttgart | 3,134 | |||||||

| 7. | Braunschweig | 3,100 | |||||||

| 8. | Essen | 3,047 | |||||||

| 9. | Aachen | 2,791 | |||||||

| 10. | Karlsruhe | 2,542 | |||||||

Illegal immigration

[edit]After 1989, the number of illegal mainland Chinese immigrants who arrived in Germany by way of Eastern Europe began to increase, only to decrease in the mid-1990s; on average, authorities caught 370 each year in the late 1990s, though they believe the actual extent of illegal migration to be much larger. Many illegal migrants work in restaurants, whose managers sponsor their migration costs and require them to pay them back.[41] Such costs usually amount between to RMB 60,000 and 120,000, paid to snakeheads (Chinese people smugglers). Due to network effects, illegal Chinese migrants to Germany largely come from the vicinity of Qingtian, Zhejiang; they are mostly men between twenty and forty years old.[42] Migrants may come as tourists and then overstay (either by applying for a tourist visa on their genuine PRC passport, or obtaining a forged passport from a country with a large Asian population whose nationals are granted visa-free travel to Germany), or they may be smuggled across the Czech-German border.[43]

Community relations and divisions

[edit]Germans generally perceive the Chinese as a monolithic group, owners of grocery stores, snack bars, and Chinese restaurants, and sometimes as criminals and triad members.[44] In actuality, the community is wracked by internal divisions, largely of political allegiances; pro-Taiwan (Republic of China) vs. pro-Mainland (People's Republic of China), supporters vs. opposers of the Chinese democracy movement, etc.[45] One rare example of the various strands of the community coming together in support of a common cause arose in April 1995, when Berlin daily Bild-Zeitung published a huge feature item alleging that Chinese restaurants in the city served dog meat; the story appears to have been sparked by an off-color quip by a German official during a press conference about a pot of mystery meat he had seen boiling in a Chinese restaurant kitchen. Chinese caterers and restaurants suffered huge declines in business, as well as personal vilification by their German neighbours.[46] The protests which the various Chinese associations organised in response carefully sidestepped the issue of German racism towards the Chinese, instead focusing mainly on the newspaper itself and the fact that it had published false statements which harmed people's businesses and livelihoods, in an effort to avoid alienating the mainstream community.[47] They eventually achieved what one scholar described as a "meagre victory": a retraction by Bild-Zeitung. However, the success of the protests laid some foundation for further professional cooperation among Chinese restaurateurs.[45]

Germany also boasts a small number of Uyghurs, a Turkic-speaking ethnic minority of China who live in the Xinjiang region in northwest China; they form one of the few obvious communities of Chinese national minorities in Europe.[48] Though they are Chinese citizens or formerly held Chinese citizenship, their ethnic and political identity is defined largely by opposition to China, and for the most part they do not consider themselves part of the Chinese community.[49] The initial Uyghur migrants to Germany came by way of Turkey, where they had settled after going into exile with the hope of one day achieving independence from China; they remigrated to Munich as a small part, numbering perhaps fifty individuals, out of the millions of gastarbeiter who came from Turkey to Germany beginning in the 1960s. Most worked in semi-skilled trades, with some privileged ones of a political bent achieving positions in the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Their numbers were later bolstered by post-Cold War migration directly from Xinjiang to Germany, also centred on Munich.[50]

In 2005, figures from Germany's Federal Statistical Office showed 71,639 People's Republic of China nationals living in Germany, making them the second-largest group of immigrants from East Asia in the country.[51] In 2005, only 3,142 Chinese, or 4.3%, were born in Germany; this was far below the average of 20% for all non-citizens.[52]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "BiB - Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung - Pressemitteilungen - Zuwanderung aus außereuropäischen Ländern fast verdoppelt". Archived from the original on 9 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Gütinger 1998, p. 206

- ^ Van Ziegert 2006, p. 162

- ^ "Chinese Buddhist centers in Germany", World Buddhist Directory, Buddha Dharma Education Association, 2006, retrieved 12 October 2008

- ^ a b Benton 2007, p. 30

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Gütinger 2004, p. 63

- ^ Gütinger 2004, p. 60

- ^ Conrad, Sebastian (2003). ""Kulis" nach Preußen? Mobilität, chinesische Arbeiter und das Deutsche Kaiserreich 1890-1914". Comparativ. 13 (4): 89 f.

- ^ Conrad, Sebastian (2003). ""Kulis" nach Preußen? Mobilität, chinesische Arbeiter und das Deutsche Kaiserreich 1890-1914". Comparativ. 13 (4): 89 f.

- ^ Gütinger 1998, p. 197

- ^ Conrad, Sebastian (2003). ""Kulis" nach Preußen? Mobilität, chinesische Arbeiter und das Deutsche Kaiserreich 1890-1914". Comparativ. 13 (4): 81–86.

- ^ a b Benton 2007, p. 31

- ^ Gütinger 2004, p. 59

- ^ Conrad, Sebastian (2003). ""Kulis" nach Preußen? Mobilität, chinesische Arbeiter und das Deutsche Kaiserreich 1890-1914". Comparativ. 13 (4): 90–93.

- ^ Benton 2007, pp. 31–32

- ^ Gütinger 1998, p. 201

- ^ Benton 2007, p. 33

- ^ Benton 2007, p. 35

- ^ Gütinger 1998.

- ^ Gütinger 1998, p. 202

- ^ "Gedenktafel Chinesenviertel Schmuckstraße". Wikimedia Commons. 17 March 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Gütinger 1998, p. 199

- ^ a b c d Gütinger 1998, p. 203

- ^ a b Christiansen 2003, p. 28

- ^ Leung 2003, p. 245

- ^ a b Gütinger 1998, p. 204

- ^ Gütinger 1998, p. 205

- ^ Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (19 December 2022). "So wollte China 1989 in letzter Minute die DDR retten". WELT (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Van Ziegert 2006, p. 153

- ^ Leung 2005, p. 324

- ^ Cheng 2002, pp. 162–163

- ^ Cheng 2002, p. 163

- ^ "China: Cultural relations", Bilateral relations, Germany: Federal Foreign Office, 2007, retrieved 21 October 2008

- ^ Cheng 2002, p. 165

- ^ Mai, Marina (7 October 2008). "Ostdeutsche Vietnamesen überflügeln ihre Mitschüler". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach ausgewählten Geburtsstaaten". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ publisher. "Publikation - Bevölkerung - Ausländische Bevölkerung - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis)". www.destatis.de.

- ^ "Naturalised persons, by selected countries of former citizenship", Foreign Population - Naturalisations, Germany: Federal Statistical Office, 2008, retrieved 21 October 2008

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (1 August 2018). "Germany's 'China City': how Duisburg became Xi Jinping's gateway to Europe". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Giese 1999, pp. 199–200

- ^ Giese 1999, p. 202

- ^ Giese 1999, pp. 206–207

- ^ Leung 2003, pp. 245–246

- ^ a b Christiansen 2003, p. 164

- ^ Christiansen 2003, p. 162

- ^ Christiansen 2003, p. 163

- ^ Christiansen 2003, p. 34

- ^ Christiansen 2003, p. 36

- ^ Christiansen 2003, p. 35

- ^ Excluding the transcontinental countries Turkey and Russia; the FSO included those two countries in the Europe total rather than that for Asia

- ^ "Foreign population on 31 December 2004 by country of origin", Population, Germany: Federal Statistical Office, 2004, archived from the original on 10 May 2007, retrieved 22 October 2008

Sources

[edit]- Benton, Gregor (2007), "Germany", Chinese Migrants and Internationalism, Routledge, pp. 30–37, ISBN 978-0-415-41868-3

- Cheng, Xi (2002), "Non-Remaining and Non-Returning: The Mainland Chinese Students in Japan and Europe since the 1970s", in Nyíri, Pál; Savelev, Igor Rostislavovich (eds.), Globalizing Chinese Migration: Trends in Europe and Asia, Ashgate Publishing, pp. 158–172, ISBN 978-0-7546-1793-8

- Christiansen, Flemming (2003), Chinatown, Europe: An Exploration of Overseas Chinese Identity in the 1990s, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1072-0

- Giese, Karsten (1999), "Patterns of Migration from Zhejiang to Germany", in Pieke, Frank; Malle, Hein (eds.), Internal and International Migration: Chinese Perspectives, Surrey, United Kingdom: Curzon Press, pp. 199–214

- Gütinger, Erich (1998), "A Sketch of the Chinese Community in Germany: Past and Present", in Benton, Gregor; Pieke, Frank N. (eds.), The Chinese in Europe, Macmillan, pp. 199–210, ISBN 978-0-312-17526-9

- Gütinger, Erich (2004), Die Geschichte Der Chinesen in Deutschland: Ein Überblick über die ersten 100 Jahre ab 1822, Waxmann Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8309-1457-0

- Kirby, William C. (1984), Germany and republican China, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-1209-5

- Leung, Maggi W. H. (2003), "Notions of Home among Diaspora Chinese in Germany", in Ma, Laurence J. C.; Cartier, Carolyn L. (eds.), The Chinese Diaspora: Space, Place, Mobility, and Identity, Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 237–260, ISBN 978-0-7425-1756-1

- Leung, Maggi (2005), "The working of networking: Ethnic networks as social capital among Chinese migrant businesses in Germany", in Spaan, Ernst; Hillmann, Felicitas; van Naerssen, A. L. (eds.), Asian Migrants and European Labour Markets: Patterns and Processes of Immigrant Labour Market Insertion in Europe, Routledge, pp. 309–331, ISBN 978-0-415-36502-4

- Van Ziegert, Sylvia (2006), Global Spaces of Chinese Culture: Diasporic Chinese Communities in the United States and Germany, CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-415-97890-3

Further reading

[edit]- Giese, Karsten (2003), "New Chinese Migration to Germany: Historical Consistencies and New Patterns of Diversification within a Globalized Migration Regime", International Migration, 41 (3): 155–185, doi:10.1111/1468-2435.00245

- Leung, Maggi Wai-han (2004), Chinese Migration in Germany: Making Home in Transnational Space, Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation, ISBN 978-3-88939-712-6