Father Le Loutre's War

| Father Le Loutre's War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

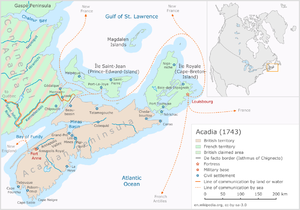

Map of Acadia, c. 1743. The conflict was primarily fought in Acadia. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Micmac War and the Anglo-Micmac War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia.[c] On one side of the conflict, the British and New England colonists were led by British Officer Charles Lawrence and New England Ranger John Gorham. On the other side, Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre led the Mi'kmaq and the Acadia militia in guerrilla warfare against settlers and British forces.[10] (At the outbreak of the war there were an estimated 2500 Mi'kmaq and 12,000 Acadians in the region.)[11]

While the British captured Port Royal in 1710, the Mi'kmaq and Acadians continued to contain the British in settlements at Port Royal and Canso. The rest of the colony was in the control of the Catholic Mi'kmaq and Acadians. About forty years later, the British made a concerted effort to settle Protestants in the region and to establish military control over all of Nova Scotia and present-day New Brunswick, igniting armed response from Acadians in Father Le Loutre's War. The British settled 3,229 people in Halifax during the first years. This exceeded the number of Mi'kmaq in the entire region and was seen as a threat to the traditional occupiers of the land.[d] The Mi'kmaq and some Acadians resisted the arrival of these Protestant settlers.

The war caused unprecedented upheaval in the area. Atlantic Canada witnessed more population movements, more fortification construction, and more troop allocations than ever before.[12] Twenty-four conflicts were recorded during the war (battles, raids, skirmishes), thirteen of which were Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on the capital region Halifax/Dartmouth. As typical of frontier warfare, many additional conflicts were unrecorded.

During Father Le Loutre's War, the British attempted to establish firm control of the major Acadian settlements in peninsular Nova Scotia and to extend their control to the disputed territory of present-day New Brunswick. The British also wanted to establish Protestant communities in Nova Scotia. During the war, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq left Nova Scotia for the French colonies of Ile St. Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Ile Royale (Cape Breton Island). The French also tried to maintain control of the disputed territory of present-day New Brunswick. (Father Le Loutre tried to prevent the New Englanders from moving into present-day New Brunswick just as a generation earlier, during Father Rale's War, Rale had tried to prevent New Englanders from taking over present-day Maine.) Throughout the war, the Mi’kmaq and Acadians attacked the British forts in Nova Scotia and the newly established Protestant settlements. They wanted to retard British settlement and buy time for France to implement its Acadian resettlement scheme.[13]

The war began with the British establishing Halifax, settling more British settlers within six months than there were Mi'kmaq. In response, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq orchestrated attacks at Chignecto, Grand Pré, Dartmouth, Canso, Halifax and Country Harbour. The French erected forts at present-day Fort Menagoueche, Fort Beauséjour and Fort Gaspareaux. The British responded by attacking the Mi'kmaq and Acadians at Mirligueche (later known as Lunenburg), Chignecto and St. Croix. The British unilaterally established communities in Lunenburg and Lawrencetown. Finally, the British erected forts in Acadian communities located at Windsor, Grand Pré and Chignecto. The war ended after six years with the defeat of the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and French in the Battle of Fort Beauséjour.

Background

Acadian resistance to British-rule in Acadia began after Queen Anne's War, with the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1713. The treaty saw the French cede portions of New France to the British, including the Hudson Bay region, Newfoundland, and peninsular Acadia. Acadians had previously supported the French in three conflicts known as the French and Indian Wars. Acadians joined French privateer Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste as crew members in his victories over many British vessels during King William's War. After the Siege of Pemaquid, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville led a force of 124 Canadians, Acadians, Mi'kmaq and Abenaki in the Avalon Peninsula Campaign. They destroyed almost every British settlement in Newfoundland, killed more than 100 British and captured many more. They deported almost 500 British colonists to England or France.[14]

During Queen Anne's War, Mi’kmaq and Acadians resisted during the Raid on Grand Pré, Pisiquit, and Chignecto in 1704. The Acadians assisted the French in protecting the capital in the First siege of Port Royal and the final second siege of Port Royal. However, with the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1713, peninsular Acadia was formally ceded to the British. Although peace was formally reestablished with France, the British still faced resistance from the French colonists in the Acadian peninsula. During Father Rale's War, the Maliseet raided numerous British vessels on the Bay of Fundy while the Mi'kmaq raided Canso in 1723. In the latter engagement, the Mi'kmaq were supported by the Acadians.[15]

During these conflicts, the French and Acadian settlers were aligned with the Mi’kmaq, fighting alongside them during the Battle of Bloody Creek[16] The Mi'kmaq, which formed a part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, had a long history of protecting their land by killing British soldiers and civilians along the New England/Acadia border in Maine. During the 17th and early-18th century, the Wabanaki fought in several campaigns, including in 1688, 1703, 1723, 1724, 1745, 1746, and in 1747.[17][e]

Hostilities between the British and French resumed during King George's War (1744–48). Supported by the French, Jean-Louis Le Loutre led a forces of French soldiers, and Acadians, and Mi’kmaq militiamen in efforts to recapture the capital, such as the Siege of Annapolis Royal.[16] During this siege, the French officer Marin had taken British prisoners and stopped with them further up the bay at Cobequid. While at Cobequid, an Acadian said that the French soldiers should have "left their [the British] carcasses behind and brought their skins."[18] Le Loutre was also joined by the prominent Acadian resistance leader Joseph Broussard (Beausoleil). Broussard and other Acadians supported the French soldiers in the Battle of Grand Pré. During King George's War, Le Loutre, Gorham and Lawrence rose to prominence in the region. During the war, however, Massachusetts Governor Shirley acknowledged that Nova Scotia was still "scarcely" British and urged London to fund building forts in the Acadian communities.[19] The signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 ended formal hostilities between British and French forces. With peace formally reestablished, the British began to consolidate its control over peninsular Acadia, leading further conflict with the Acadian and Mi'kmaq.

At the outset of Le Loutre's war, along with the New England Ranger units, there were three British regiments at Halifax, the 40th Regiment of Foot arrived from Annapolis, while the 29th Regiment of Foot (Peregrine Hopson's regiment) and 45th Regiment of Foot (Hugh Warburton's regiment) arrived from Louisbourg. The 47th Regiment (Peregrine Lascelles' regiment) arrived the following year (1750). At sea, Captain John Rous was the senior naval officer on the Nova Scotia station during the war.[f] The main officer under his command was Silvanus Cobb.[g] John Gorham also owned two armed schooners: the Anson and the Warren.[20][h]

Course of war

1749

British consolidation of Nova Scotia

The war began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.[22] The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (Citadel Hill in 1749), Bedford (Fort Sackville in 1749), Dartmouth (1750), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754).

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British attempted to take control of the Nova Scotia peninsula by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor (Fort Edward); Grand Pré (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). A British fort (Fort Anne) already existed at the other major Acadian centre of Annapolis Royal and Cobequid remained without a fort. Le Loutre is reported to have said that "the English might build as many Forts as they pleased but he wou'd take care that they shou'd not come out of them, for he was resolved to torment them with his Indians...."[23][j] In fact, Mi'kmaq resistance kept the British largely holed up in their forts until the fall of Louisbourg (1758).[24]

By June 1751, Cornwallis wrote to the Board of Trade that his adversaries had "done as much harm to as they could have done in open war."[26] Richard Bulkeley wrote that between 1749 and 1755, Nova Scotia "was kept in an uninterrupted state of war by the Acadians... and the reports of an officer commanding Fort Edward, [indicated he] could not be conveyed [to Halifax] with less an escort than an officer and thirty men."[25] (Along with Bulkeley, Cornwallis' other Aide-de-camp was Horatio Gates.)

The only land route between Louisbourg and Quebec went from Baie Verte through Chignecto, along the Bay of Fundy and up the Saint John River.[27] With the establishment of Halifax, the French recognized at once the threat it represented and that the Saint John River corridor might be used to attack Quebec City itself.[28] To protect this vital gateway, at the beginning of 1749, the French strategically constructed three forts within 18 months along the route: one at Baie Verte (Fort Gaspareaux), one at Chignecto (Fort Beausejour) and another at the mouth of the Saint John River (Fort Menagoueche).

In response to Gorham's raid on the Saint John River in 1748, the Governor of Canada threatened to support native raids along the northern New England border.[26] There were many previous raids from the Mi'kmaq militia and Maliseet Militias against British settlers on the border (1703, 1723, 1724, 1745, 1746, 1747). During the war, along the former border of Acadia, the Kennebec River, the British built Fort Halifax (Winslow), Fort Shirley (Dresden, formerly Frankfurt) and Fort Western (Augusta).[k]

Acadian Exodus

With demands for an unconditional oath, the British fortification of Nova Scotia, and the support of French policy, a significant number of Acadians made a stand against the British. On 18 September 1749, a document was delivered to Edward Cornwallis signed by a total of 1000 Acadians, with representatives from all the major centres. The document stated that they would leave the country before they would sign an unconditional oath.[31] Cornwallis continued to press for the unconditional oath rejecting their Christian Catholic Faith and accepting the Protestant Anglican Church with a deadline of 25 October. In response, hundreds of Acadians were deported by the British with the confiscation of their homes, their lands and their cattle. The deportation of the Acadians by the British involved almost half of the total Acadian population of Nova Scotia. The expulsion was brutal often separating children from their families. The leader of the Exodus was Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre, whom the British gave the code name "Moses".[32] Historian Micheline Johnson described Le Loutre as "the soul of the Acadian resistance."[2]

Conflict begins

The first Mi'kmaq breach of the Treaty of 1726 and 1748 was at Canso. On 19 August 1749, Lieutenant Joseph Gorham, younger brother of John Gorham (military officer), was under the command of William Clapham at Canso and his party was attacked by Mi'kmaq.[33][34] They seized his vessel and took twenty prisoners and carried them off to Louisbourg ten days later on the 29th. After Cornwallis complained to the Governor of Ile Royale, sixteen of the prisoners were released to Halifax and the other four sent off on their own vessel.[35] The year earlier the Mi'kmaq had seized Captain Ellingwood's vessel Success and he promised them 100 pounds and left his son hostage to have it released. Mikmaq reported they released the prisoners from Canso. because Captain Ebenezer Ellingwood had paid the money but had not returned for his son.[36][26][l]

At the Isthmus of Chignecto in August 1749, the Mi'kmaq attacked two British vessels thought to be preventing Acadians from joining the Acadian Exodus by leaving Beaubassin for Ile St. Jean.[38] On September 18, several Mi'kmaq and Maliseets ambushed and killed three British men at Chignecto. Seven natives were killed in the skirmish.[39]

On 24 September 1749, the Mi'kmaq formally wrote to Governor Cornwallis through French missionary Father Maillard, proclaiming their ownership of the land, and expressing their opposition to the British actions in settling at Halifax. Some historians have read this letter as declaration of hostility against the British.[40] Other historians have questioned that interpretation.[41]

On September 30, 1749, about forty Mi'kmaq attacked six men during the Raid on Dartmouth. The six men, under the command of Major Gilman, were in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia cutting trees near a saw mill. Four of them were killed on the spot, one was taken prisoner and one escaped.[42][m] Two of the men were scalped and the heads of the others were cut off. Major Ezekiel Gilman and others in his party escaped and gave the alarm. A detachment of rangers was sent after the raiding party and cut off the heads of two Mi'kmaq and scalped one.[43] This raid was the first of eight against Dartmouth during the war.

This raid was consistent with the Wabanaki Confederacy and New England's approach to warfare with each other since King William's War (1688).[n]

Cornwallis' proclamation

On October 1, 1749, Cornwallis convened a meeting of the Nova Scotia Council aboard HMS Beaufort. According to the minutes, in keeping with earlier treaties, the Council determined that they would treat the Mi'kmaq as rebellious British subjects rather than as war adversaries: "That, in their opinion to declare war formally against the Micmac Indians would be a manner to own them a free and independent people, whereas they ought to be treated as so many Banditti Ruffians, or Rebels, to His Majesty's Government."[44]

On October 2, 1749, the Nova Scotia Council issued the extirpation proclamation against the Mi’kmaq on peninsular Nova Scotia and those that assist them. The intent of the proclamation was to stop native raids on the British and to pressure the natives into "submission" to establish "peace and friendship." The proclamation outlined four strategies for people to pressure the natives: "annoy" them, "distress" them, kill them or take them prisoner. There was also a bounty of 10 guinea given for a native killed or taken prisoner. The proclamation reads:

"For, those cause we by and with the advice and consent of His Majesty's Council, do hereby authorize and command all Officers Civil and Military, and all His Majesty's Subjects or others to annoy, distress, take or destroy the Savage commonly called Micmac, wherever they are found, and all as such as aiding and assisting them, give further by and with the consent and advice of His Majesty's Council, do promise a reward of ten Guineas for every Indian Micmac taken or killed, to be paid upon producing such Savage taken or his scalp (as in the custom of America) if killed to the Officer Commanding."[44]

To carry out this task, two companies of rangers were raised, one led by Captain Francis Bartelo and the other by Captain William Clapham. These two companies served alongside that of John Gorham's company. The three companies scoured the land around Halifax looking for Mi'kmaq. Three days after the bounty was ordered, on October 5, Governor Cornwallis sent Commander White with troops in the 20-gun sloop Sphinx to Mirligueche (Lunenburg).[45]

After two consecutive attacks on June 18 and then June 20, 1750 Cornwallis deemed the initial proclamation ineffective and increased the bounty to 50 guinea on June 21, 1750. During Cornwallis' tenure there is evidence of one scalp being taken, no prisoners and three non-combatants being killed - three youth in 1752.[46]

Siege of Grand Pré

Two months later, on November 27, 1749, 300 Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Acadians attacked Fort Vieux Logis, recently established by the British in the Acadian community of Grand Pré. The fort was under the command of Captain Handfield. The Native and Acadian militia killed the sentries (guards) who were firing on them.[47] The Natives then captured Lieutenant John Hamilton and eighteen soldiers under his command, while surveying the fort's environs. After the British soldiers were captured, the native and Acadian militias made several attempts over the next week to lay siege to the fort before breaking off the engagement. Gorham's Rangers was sent to relieve the fort. When he arrived, the militia had already departed with the prisoners. The prisoners spent several years in captivity before being ransomed.[48] There was no fighting over the winter months, which was common in frontier warfare.

1750–1751

Battle at St. Croix

The following spring, on March 18, 1750, John Gorham and his Rangers left Fort Sackville (at present day Bedford, Nova Scotia), under orders from Governor Cornwallis, to march to Piziquid (present day Windsor, Nova Scotia). Gorham's mission was to establish a blockhouse at Pisiquid, which became Fort Edward, and to seize the property of Acadians who had participated in the siege of Grand Pré.

Arriving at about noon on March 20 at the Acadian village of Five Houses beside the St. Croix River, Gorham and his men found all the houses deserted. Seeing a group of Mi’kmaq hiding in the bushes on the opposite shore, the Rangers opened fire. The skirmish deteriorated into a siege, with Gorham's men taking refuge in a sawmill and two of the houses. During the fighting, the Rangers suffered three wounded, including Gorham, who sustained a bullet in the thigh. As the fighting intensified, a request was sent back to Fort Sackville for reinforcements.[49]

Responding to the call for assistance on March 22, Governor Cornwallis ordered Captain Clapham's and Captain St. Loe's Regiments, equipped with two field guns, to join Gorham at Piziquid. The additional troops and artillery turned the tide for Gorham and forced the Mi’kmaq to withdraw.[50]

Gorham proceeded to present-day Windsor and forced Acadians to dismantle their church – Notre Dame de l'Assomption – so that Fort Edward could be built in its place.

Battles at Chignecto

In May 1750, Lawrence was unsuccessful in establishing himself at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, thereby preventing Lawrence from using the supplies of the village to establish a fort. (According to historian Frank Patterson, the Acadians at Cobequid burned their homes as they retreated from the British to Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia in 1754.[51]) Lawrence retreated only to return in September 1750.

On September 3, 1750 New England Ranger John Gorham led over 700 men to the Isthmus of Chignecto. Mi’kmaq and Acadians opposed the landing and killed twenty British. Several Mi’kmaq were killed and they were eventually overwhelmed by the invading force and withdrew, burning their crops and houses as they retreated.[52] On 15 October (N.S.) a group of Micmacs disguised as French officers called a member of the Nova Scotia Council Edward How to a conference. This trap, organized by Chief Étienne Bâtard, gave him the opportunity to wound How seriously, and How died five or six days later, according to Captain La Vallière (probably Louis Leneuf de La Vallière), the only eyewitness.[53]

Le Loutre and Acadian militia leader Joseph Broussard resisted the British assault. The British troops defeated the resistance and began construction of Fort Lawrence near the site of the ruined Acadian village of Beaubassin.[54] The work on the fort proceeded rapidly and the facility was completed within weeks. To limit the British to peninsular Nova Scotia, the French began also to fortify the Chignecto and its approaches, constructing Fort Beausejour and two satellite forts – one at present-day Port Elgin, New Brunswick (Fort Gaspareaux) and the other at present-day Saint John, New Brunswick (Fort Menagoueche).[55]

During these months, 35 Mi'kmaq and Acadians ambushed Ranger Francis Bartelo, killing him and six of his men while taking seven others captive. The captives' bloodcurdling screams as the Mi'kmaq tortured them throughout the night had a chilling effect on the New Englanders.[52]

Raids on Halifax

There were four raids on Halifax during the war. The first raid happened in October 1750, while in the woods on peninsular Halifax, Mi'kmaq scalped two British people and took six prisoner: Cornwallis' gardener, his son, and Captain William Clapham's book keeper were tortured and scalped. The Mi'kmaq buried the son while the gardener's body was left behind and the other six persons were taken prisoner to Grand Pre for five months.[56][o] Shortly after this raid, Cornwallis learned that the Mi'kmaq had received payment from the French at Chignecto for five prisoners taken at Halifax as well as prisoners taken earlier at Dartmouth and Grand Pre.[57]

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouses surrounding Halifax. Mi'kmaq attacked the North Blockhouse (located at the north end of Joseph Howe Drive) and killed the men on guard. Mi'kmaq also attacked near the South Blockhouse (located at the south end of Joseph Howe Drive), at a saw-mill on a stream flowing out of Chocolate Lake into the Northwest Arm. They killed two men.[58]

Battle off Baie Verte

In August 1750, there was a naval battle off Baie Verte between British Captain Le Cras, of the Trial and the French sloop, London, of 70 tons. The London was seized to discover that it had been employed to carry stores of all kinds, arms, and ammunition, from Quebec to Le Loutre and the Mi'kmaq fighters. François Bigot, the intendant of New France had given instructions to the French captain to follow the orders of Le Loutre or La Corne, the bills of lading endorsed by Le Loutre, and other papers and letters, were found on board of her, with four deserters from Cornwallis' regiment, and a family of Acadians. The prize and her papers were sent to Halifax.[59]

Port Joli

About 1750, the Mi'kmaq captured a New England fishing schooner off of Port Joli and tortured the crew members. To the west of St. Catherines River, the Mi'kmaq heated "Durham Rock" and forced each crew member to burn on the rock or jump to their death into the ocean.[60]

Battle off Port La Tour (1750)

In mid September 1750 French officer Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor (later the commander at Fort Beausejour)[61] was dispatched aboard the brigantine Saint-François to convoy the schooner Aimable Jeanne, which was carrying munitions and supplies from Quebec to the Saint John River for Boishebert at Fort Boishebert. Early on 16 October, about ten leagues west of Cape Sable (present-day Port La Tour, Nova Scotia and area), British Captain John Rous in HMS Albany overtook the French vessels.[62] Despite inferior armament, Vergor engaged the sloop, allowing Aimable Jeanne to reach Fort Boishebert. The action lasted the better part of the day, after which, with only seven men fit out of 50 and Saint-François unmasted and sinking, Vergor was obliged to yield.[63] Three of Rous' crew were killed. The French ship contained a large quantity of provision, uniforms and warlike supplies.[64] Cornwallis noted that this action was the second time he had caught the Governor of Canada sending a ship of military supplies to the Mi'kmaq to use against the British.[65] By the end of the year, Cornwallis estimated that there were no less than eight to ten French vessels which unloaded war supplies for the Mi'kmaq, French, and Acadians at Saint John River and Baye Vert.[66] In response to their defeat in the Battle off Port La Tour, the Governor of Canada ordered four British sloops to be seized at Louisbourg.[67]

Raids on Dartmouth

There were six raids on Dartmouth during this time period. In July 1750, the Mi'kmaq killed and scalped 7 men who were at work in Dartmouth.[68]

In August 1750, 353 people arrived on the Alderney and began the town of Dartmouth. The town was laid out in the autumn of that year.[69] The following month, on September 30, 1750, Dartmouth was attacked again by the Mi'kmaq and five more residents were killed.[52] In October 1750 a group of about eight men went out "to take their diversion; and as they were fowling, they were attacked by the Indians, who took the whole prisoners; scalped ... [one] with a large knife, which they wear for that purpose, and threw him into the sea ..."[56]

The following spring, on March 26, 1751, the Mi'kmaq attacked again, killing fifteen settlers and wounding seven, three of which would later die of their wounds. They took six captives, and the regulars who pursued the Mi'kmaq fell into an ambush in which they lost a sergeant killed.[70] Two days later, on March 28, 1751, Mi'kmaq abducted another three settlers.[70]

Two months later, on May 13, 1751, Broussard led sixty Mi'kmaq and Acadians to attack Dartmouth again, in what would be known as the "Dartmouth Massacre".[71] Broussard and the others killed twenty settlers – mutilating men, women, children and babies – and took more prisoners.[70][p] A sergeant was also killed and his body mutilated. They destroyed the buildings. The British returned to Halifax with the scalp of one Mi'kmaq warrior, however, they reported that they killed six Mi'kmaq warriors.[72] Captain William Clapham and sixty soldiers were on duty and fired from the blockhouse.[71] The British killed six Mi'kmaq warriors, but were only able to retrieve one scalp that they took to Halifax.[72] Those at a camp at Dartmouth Cove, led by John Wisdom, assisted the settlers. Upon returning to their camp the next day they found the Mi'kmaq had also raided their camp and taken a prisoner. All the settlers were scalped by the Mi'kmaq. The British took what remained of the bodies to Halifax for burial in the Old Burying Ground.[73][q]

Raid on Chignecto

The British retaliated for the raid on Dartmouth by sending several armed companies to Chignecto. A few French defenders were killed and the dikes were breached. Hundreds of acres of crops were ruined which was disastrous for the Acadians and the French troops.[74] In the summer of 1752 Father Le Loutre went to Quebec and then on to France to advocate for supplies to re-build the dikes. He returned in the spring of 1753.

1752–1753

In 1752, the Mi'kmaq attacks on the British along the coast, both east and west of Halifax, were frequent. Those who were engaged in the fisheries were compelled to stay on land because they were the primary targets.[75] In early July, New Englanders killed and scalped two Mi'kmaq girls and one boy off the coast of Cape Sable (Port La Tour, Nova Scotia).[76] In August, at St. Peter's, Nova Scotia, Mi'kmaq seized two schooners – the Friendship from Halifax and the Dolphin from New England – along with 21 prisoners who were captured and ransomed.[76]

By the summer of 1752, the war had not been going well for the British. The Acadian Exodus remained strong. The war had bankrupted the colony.[77] As well, two of the three ranger leaders had died. In August 1751, the main ranger leader John Gorham left for London and died there of disease in December. Ranger leader Captain Francis Bartelo had been killed in action at Chignecto, while the other ranger leader Captain William Clapham had been disgraced, failing to prevent the Dartmouth Massacre. John Gorham was succeeded by his younger brother Joseph Gorham. In 1752, to reduce the expense of the war, the companies raised in 1749 were disbanded, bringing down the strength of the unit to only one company.[77] This reduction led to the 22 March 1753 resolution for a militia that would be raised from the colonists to establish the security of the colony, in which all British subjects between the ages of 16 and 60 were compelled to serve.[78] On April 21, 1753, at Torbay, the Mi'kmaq fighters killed two British.[79] Throughout 1753, French authorities on Cape Breton Island were paying Mi'kmaq warriors for the scalps of the British.[80] In June 1753, the London Magazine reported that "the war with the Indians hath hitherto hindered the inhabitants going far into the woods."[81]

On 14 September 1752 Governor Peregrine Hopson and the Nova Scotia Council negotiated the Treaty of 1752 with Jean-Baptiste Cope. (The treaty was signed officially on November 22, 1752.) Cope was unsuccessful in getting support for the treaty from other Mi'kmaq leaders. Cope burned the treaty six months after he signed it.[82] Despite the collapse of peace on the eastern shore, the British did not formally renounce the Treaty of 1752 until 1756.[83]

Attack at Mocodome

On February 21, 1753, nine Mi'kmaq from Nartigouneche (present-day Antigonish, Nova Scotia) in canoes attacked a British vessel at Country Harbour. The vessel was from Canso and had a crew of four. The Mi'kmaq fired on them and drove them toward the shore. Other natives joined in and boarded the schooner, forcing them to run their vessel into an inlet. The Mi'kmaq killed and scalped two of the British and took two others captive. After seven weeks in captivity, on April 8, the two British prisoners – one of which was John Connor – killed six Mi'kmaq and managed to escape.[84][r] The Mi'kmaq account of this attack was that the two English died of natural causes and the other two killed seven of the Mi'kmaq for their scalps.

Attack at Jeddore

In response, on the night of April 21, under the leadership of Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope and the Mi'kmaq attacked another British schooner in a battle at sea off Jeddore, Nova Scotia. On board were nine British men and one Acadian (Casteel), who was the pilot. The Mi'kmaq killed and scalped the British and let the Acadian off at Port Toulouse, where the Mi'kmaq sank the schooner after looting it.[85] In August 1752, the Mi'kmaq at Saint Peter's seized the schooners Friendship of Halifax and Dolphin of New England and took 21 prisoners who they held for ransom.[76] In May 1753, natives scalped two British soldiers at Fort Lawrence.[86]

Raid on Halifax

In late September 1752, Mi’kmaq scalped a man they had caught outside the palisade of Fort Sackvillle.[87] In 1753, when Lawrence became governor, the Mi'kmaq attacked again upon the sawmills near the South Blockhouse on the Northwest Arm, where they killed three British. The Mi'kmaq made three attempts to retrieve the bodies for their scalps.[88] On the otherside of the harbour in Dartmouth, in 1753, there were reported only to be five families, all of whom refused to farm for fear of being attacked if they left the confines of the picketed fence around the village.[89] On 23 July 1753, Governor Hobson reported to the Board of Trade on the "continual war we have with the Indians."[26] Governor Hobson in his letter to the Board of Trade, dated 1 October 1753, says, "At Dartmouth there is a small town well picketed in, and a detachment of troops to protect it, but there are not above five families residing in it, as there is no trade or fishing to maintain any inhabitants, and they apprehend danger from the Indians in cultivating any land on the outer side of the pickets."[90]

The Lunenburg Rebellion

In the spring of 1753, it became public knowledge that the British were planning to unilaterally establish the settlement of Lunenburg, that is, without negotiating with the Mi'kmaq people. The British decision was a continuation of violations of an earlier treaty and undermined Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope's 1752 Peace Treaty.[91] As a result, Governor Peregrine Hopson received warnings from Fort Edward that as many as 300 natives nearby were prepared to oppose the settlement of Lunenburg and intended to attack upon the arrival of settlers.[92] The move was part of the British government campaign to establish Protestants in Nova Scotia against the power of Catholic Acadians. This also served the dual purpose of getting rid of Foreign Protestants from Halifax that had become problematic out of their frustration due to mistreatment by the British.[93]

In June 1753, 1400 German and French Protestant settlers, supervised by Lawrence and protected by the British Navy ships, a unit of Regular soldiers under Major Patrick Sutherland, and a unit of rangers under Joseph Gorham, established the village of Lunenberg.[94] The settlement was founded by two British army officers John Creighton and Patrick Sutherland and German-immigrant local official Dettlieb Christopher Jessen.

In August 1753, Le Loutre paid Mi'kmaq for 18 British scalps which they took from the English in different incursions that they had made on their establishments over the summer.[95]

In mid December 1753, within six months of their arrival at Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, the new settlers, who were mostly Foreign Protestants and weary from resettlement and poor conditions,[93] rebelled against the British. They were supported by Le Loutre.[s] The rebellion is often referred to as "The Hoffman Insurrection," because it was led by John Hoffman, one of the army captains who had established the settlers in the town. Hoffman led a mob that eventually locked up in one of the blockhouses the Justice of the Peace and some of Commander Patrick Sutherland's troops. The rebels then declared a republic. Commander Patrick Sutherland at Lunenburg asked for reinforcements from Halifax and Lawrence sent Colonel Robert Monckton with troops to restore order. Monckton arrested Hoffman and took him to Halifax. Hoffman was charged with planning to join the French and take a large number of settlers with him.[98] He was fined and imprisoned on Georges Island (Nova Scotia) for two years.[98] After the rebellion a number of the French and German-speaking Foreign Protestants left the village to join Le Loutre and the Acadians.[99] Lawrence and his deputy refused to send Acadians to the area for fear of their influence on the local population.[97]

Dyking on riviere Au Lac

Le Loutre and the Acadian refugees at Chignecto struggled to create dykes that would support the new communities that resulted from the Acadian Exodus. In the first winter (1749), the Acadians survived on rations waiting for the dykes to be built. Acadians from Minas were a constant support in providing provisions and labour on the dykes. In retaliation for the Acadian and Mi’kmaq Raid on Dartmouth (1751), the British raided Chignecto destroying the dykes and ruining hundreds of acres of crops.[100] Acadians began to defect from the exodus and made application to return to the British colony.[101] Le Loutre immediately sought help from Quebec and then France to support re-building dykes in the area. He returned with success in May 1753 and work began on the grand dyking project on riviere Au Lac (present day Aulac River, New Brunswick).[102] At this time, there were 2000 Acadians and about 300 Mi'kmaq encamped near-by.[95]

By the summer of 1754, Le Loutre's amazing engineering feats manifested themselves on the great sweeping marshlands of the isthmus; he now had in his workforce and within a forty-eight-hour marching radius about 1400 to 1500 Acadian men. Nearby at Baie Verte there was a summer encampment of about 400 natives that would have been one of the largest concentrations of Native people in the Atlantic region at the time. Altogether, he had a substantial fighting force capable of defending itself against anything the Nova Scotia Government might have mustered at the time.[103] Unfortunately, that year storm tides broke through the main cross-dike of the large-scale reclamation project, destroying nearly everything the Acadians had accomplished in several months of intense work. Again some Acadians tried to defect to the British.[104]

1754–1755

Raid on Lawrencetown

In 1754, the British established Lawrencetown. In late April 1754, Beausoleil and a large band of Mi'kmaq and Acadians left Chignecto for Lawrencetown.[105] They arrived in mid-May and in the night open fired on the village. Beausoleil killed and scalped four British settlers and two soldiers. By August, as the raids continued, the residents and soldiers were withdrawn to Halifax.[106] By June 1757, the settlers had to be withdrawn completely again from the settlement of Lawrencetown because the number of Native raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses.[107]

Prominent Halifax business person Michael Francklin was captured by a Mi'kmaq raiding party in 1754 and held captive for three months.[108] Another captivity narrative was written by Henry Grace was taken captive by the Mi'kmaq near Fort Cumberland in the early 1750s. The narrative was entitled, "The History of the Life and Sufferings of Henry Grace" (Boston, 1764).[109]

Port Joli

In 1754, late one evening, a canoe full of Mi'kmaq fighters attempted to destroy the rudder of a New England fishing vessel. The New England crew sank the canoe and all the Mi'kmaq drowned except Molly Pigtow who was captured and taken back to New England.[60]

Battle off Port La Tour (1755)

In April 1755, while searching for a wrecked vessel at Port La Tour, Cobb discovered the French schooner Marguerite (Margarett), taking war supplies to the Saint John River for Boishebert at Fort Menagoueche. Cobb returned to Halifax with the news and was ordered by Governor Charles Lawrence to blockade the harbour until Captain William Kensey arrived in the warship HMS Vulture, and then to assist Kensey in capturing the French prize and taking it to Halifax.[110][111]

In the action of 8 June 1755, a naval battle off Cape Race, Newfoundland, the British found on board the French ships Alcide and Lys 10,000 scalping knives for Acadians and Indians serving under Mi'kmaq Chief Cope and Acadian Beausoleil as they continued to fight Father Le Loutre's War.[112] The British also thwarted French supplies from reaching Acadians and Mi'kmaq resisting the British in the previous war, King George's War—see First Battle of Cape Finisterre (1747).[113]

Battle of Fort Beauséjour

On May 22, 1755, the British commanded a fleet of three warships and thirty-three transports carrying 2,100 soldiers from Boston, Massachusetts; they landed at Fort Lawrence on June 3, 1755. The following day the British forces attacked Fort Beausejour using the plan created by spy Thomas Pichon. After the Fort's capitulation the French forces evacuated on June 16, 1755 to Fort Gaspereaux en route to Louisbourg, arriving on June 24, 1755. Shortly after, Monckton dispatched Captain John Rous to take Fort Menagoueche at the mouth of the St. John River. Boishebert, seeing that resistance was futile, destroyed the fort and retreated upriver to Belleisle Bay. There he erected a camp volant and constructed a small battery as a rear guard for the Acadian settlements on the river.[114] which the French destroyed themselves to prevent it from falling into British hands. This battle proved to be one of the key victories for the British in the Seven Years' War, in which Great Britain gained control of nearly all of New France.[115][t]

Trade during the war

During Father Le Loutre's War, Minas Basin communities willingly responded to the call from Le Loutre for basic food stuffs. The bread basket of the region, they raised wheat and other grains, produced flour in no fewer than eleven mills, and sustained herds of several thousand head of cattle, sheep and hogs. Regular cattle droves made their way over a road from Cobequid to Tatamagouche for the supply of Beausejour, Louisbourg, and settlements on Ile St. Jean. Other exports went by sea from Minas Basin to Beaubassin or to the mouth of the St. John River, carried in Acadian vessels by Acadian middlemen.[116]

At the same time, Acadians began to refuse to trade with the British. By 1754, no Acadian produce was reaching the Halifax market. While the French pressured Acadians not to trade with Halifax, even when British merchants tried to buy directly from Acadians, they were refused. Acadians refused to supply Fort Edward with any firewood.[117] Lawrence passed a Corn Law, forbidding Acadian exports until Halifax market had been supplied.[117] The British devised a war plan for Nova Scotia that focused on cutting off the food supply to Fort Beauséjour and Louisbourg. This plan involved both siege tactics but also cutting of the source of the supply.[118]

Aftermath

Father Le Loutre's War had done much to create the condition of total war; British civilians had not been spared, and, as Lawrence saw it, Acadian civilians had provided intelligence, sanctuary, and logistical support while others actually fought in armed conflict.[119]

More than any other single factor – including the massive assault that eventually forced the surrender of Louisbourg – the supply problem spelled doom to French power in the region. To cut off the supply to the French, Lawrence realized he could do this, in part, by deporting the Acadians.[120]

With the fall of Beausejour, Le Loutre was imprisoned and the Acadian expulsion began. During the French and Indian War, the British forces rounded up French settlers starting with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). The British deported the Acadians and burned their villages at Chignecto to prevent their return.

The Acadian Exodus from Nova Scotia during the war spared most of those who joined it – particularly those who went to Ile St. Jean and Ile Royal – from the British expulsion of the Acadians in 1755. However, with the fall of Louisbourg in 1758, the Acadians who left for the French colonies were deported as well.

See also

- American Indian Wars

- Colonial American military history

- Franco-Indian alliance

- Military history of Canada

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of the Acadians

- Military history of the Mi’kmaq People

Notes

- ^ See Battle at St. Croix

- ^ Irish officer, 1749–50, later Major, 1775; Lieut. in Gorham's Rangers by 1754[9] and later he was in the 59th Regiment of Foot. Richard Bulkeley Senr. excepted, Moncrieffe was the only charter member of The Charitable Irish Society of Halifax also to have come to Nova Scotia with Governor Edward Cornwallis in 1749 (Nova Scotia Archives). In the 59th regiment he fought under Thomas Cage in Boston during the American Revolution. He later returned to Halifax.

- ^ John Grenier developed the "Father Le Loutre's War" frame on these series of conflicts in his books The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. 2008. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3. and The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607–1814. 2005. ISBN 978-1-139-44470-5..

- ^ 2576 settlers arrived with Cornwallis; the following year, 353 arrived on the Alderney; 300 Foreign Protestants also arrived. Akins (1895), pp. 5, 27

- ^ The focus of the raids were the towns on the Acadia/ New England border: A line drawn from Falmouth, now Portland, on Casco Bay, by the towns Scarborough, Saco, Wells, York, Amesbury, Haverhill, Andover, Dunstable, Chelmsford, Groton, Lancaster, and Worcester constituted the frontier of Massachusetts, which then included Maine.

- ^ Rous was first in command of the 14-gun HMS Albany and then in 1753 took over the 14-gun HMS Success.

- ^ Cobb captained the sloop York and then the 80-ton York and Halifax.

- ^ Anson, of 70 tons, John Beare, commander, and Daniel Dimmock, lieutenant, and the schooner Warren, of 70 tons, Jonathan Davis, captain, and Benjamin Myrick, lieutenant. Murdoch (1866), p. 122.

- ^ Horsemens Fort was named after Col. John Horseman of Warburton's Regiment (45th Regiment) who was a member of the Nova Scotia Council[21]

- ^ On September 4, 1751, Cornwallis acknowledged the difficulties of creating safety beyond the forts: "Farmers can't live within Forts and must go in security upon their business..." Akins (1869), p. 644

- ^ Attacks on these forts continued through Father Le Loutre's War.[29] Charles Morris had intelligence from Acadians that another Northeast Coast Campaign was planned for 1755.[30]

- ^ Ellinwood's son Ebenezer Jr. was age 4 and would later also become a sea captain.[37]

- ^ For the primary sources that document the Raids on Dartmouth see Salusbury (2011); Wilson (1751); and Landry (2007), " Part 5, Chapter 7: The Indian Threat (1749–58)"

- ^ By the time Cornwallis had arrived in Halifax, there was a long history of the Wabanaki Confederacy (which included the Mi'kmaq) killing British soldiers and civilians along the New England/ Acadia border in Maine (See the Northeast Coast Campaigns 1688, 1703, 1723, 1724, 1745, 1746, 1747).

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 334, puts the month of this raid in July and writes that there were six British attacked, two were scalped and four were taken prisoner and never seen again.

- ^ Cornwallis' official report mentioned that four settlers were killed and six soldiers taken prisoner. See Governor Cornwallis to Board of Trade, letter, June 24, 1751, referenced in Chapman (2001), p. 29. Wilson (1751) reported that fifteen people were killed immediately, seven were wounded, three of whom would die in hospital; six were carried away and never seen again".

- ^ Trider, Douglas William (1999). History of Halifax and Dartmouth Harbour: 1415–1800. Vol. Vol. I. Self Published. p. 69.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) list the 34 people who were buried in Halifax between May 13 – June 15, 1751, four of whom were soldiers. - ^ Patterson (1993), p. 43, reports the attack happened on the coast between Country Harbour and Tor Bay. Whitehead (1991), p. 137, reports the location was a little harbour to the westward of Torbay, "Martingo", "port of Mocodome"; Murdoch (1865), p. 410, identifies Mocodome as present-day "Country Harbour". The Mi'kmaq claimed the British schooner was accidentally shipwrecked and some of the crew drowned. They also indicated that two men died of illness while the other killed the six Mi'kmaq despite their hospitality. The French officials did not believe the Mi'kmaq account of events.

- ^ Le Loutre in his autobiography notes that his work extended to Lunenburg and Cape Sable, that is, Nova Scotia's South Shore.[96] Lawrence and his deputy also refused to send Acadians to the area for fear of their influence on the local population.[97]

- ^ On the isthmus, the British renamed Fort Beauséjour to Fort Cumberland and abandoned Fort Lawrence; they recognized the superior construction of Fort Beauséjour. They also renamed Fort Gaspareaux to Fort Moncton.

References

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1979). "Germain, Charles". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ a b Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Daudin, Henri". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1979). "Girard, Jacques". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Manach, Jean". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Sutherland, Maxwell (1979). "Brewse, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ https://www.oakislandcompendium.ca/blockhouse-blog/tracking-jeremiah-rogers-privateer-to-oak-island

- ^ George E. E. Nichols, "Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers", Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, March 15, 1904

- ^ Burke, Edmund (1786). "The Annual Register, Or, A View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year".

- ^ "Monthly Chronologer". The London Magazine. Vol. 23. 1754. p. 474.

- ^ Grenier (2008), p. 148.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 127.

- ^ Johnson, John (2005). "French attitudes toward the Acadians". In Ronnie Gilles LeBlanc (ed.). Du Grand Dérangement à la Déportation: nouvelles perspectives historiques. Université de Moncton. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-897214-02-2.

- ^ Grenier (2008), pp. 154–155; Patterson (1993), p. 47.

- ^ Reid, John G. (1994). "1686–1720: Imperial Intrusions". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR j.ctt15jjfrm.

- ^ Grenier (2008), pp. 46–73.

- ^ a b Faragher (2005), pp. 110–112.

- ^ Scott, Tod (2016). "Mi'kmaw Armed Resistance to British Expansion in Northern New England (1676–1781)". Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society Journal. 19: 1–18.

• Reid, John G.; Baker, Emerson W. (2008). "Amerindian Power in the Early Modern Northeast: A Reappraisal". Essays on Northeastern North America, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of Toronto Press. pp. 129–152. doi:10.3138/9781442688032. ISBN 978-0-8020-9137-6. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442688032.12.

• Grenier (2008) - ^ Pote, William (1895). The Journal of Captain William Pote, Jr: During His Captivity in the French and Indian War from May, 1745, to August, 1747. Dodd, Mead & Company. p. 34.

- ^ Baxter, James Phinney, ed. (1908). Documentary history of the state of Maine. Vol. Volume XI. Portland, Maine: Maine Historical Society.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

• Lincoln, Charles Henry, ed. (1912). "Massachusetts General Court: Report on French Encroachments, April 18, 1749". Correspondence of William Shirley: Governor of Massachusetts and Military Commander in America 1731–1760. Vol. Vol. I. p. 481.{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Bates, George (1954). "John Gorham 1709–1751: An outline of his activities in Nova Scotia". Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. XXX: 45.

- ^ Akins (1869), p. 572.

- ^ Grenier (2008); Akins (1895), p. 5.

- ^ Patterson (1993), p. 47.

- ^ West, Jerry (October 22, 2015). "Mi'kmaq resistance kept British holed up in their forts, historian finds". CBC News.

- ^ a b Nova Scotia Historical Society (1881), p. 151.

- ^ a b c d Akins (1869).

- ^ Campbell (2005), p. 25.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 131.

- ^ Collections and Proceedings of the Maine Historical Society. Vol. Second Series, Vol. X. Portland, Maine. 1899.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Baxter, James Phinney, ed. (1908). Documentary history of the state of Maine. Vol. Volume XII. Portland, Maine: Maine Historical Society. p. 266.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Griffiths (2005), p. 384; Faragher (2005), p. 254

- ^ Akins (1869), p. 230.

- ^ Salusbury (2011); Akins (1869)

- ^ Picheon, p. 278

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 18; Wicken (2002), p. 179

- ^ Urban, Sylvanius (1748). "List of Ships Taken". The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle. Vol. 18. Edw. Cave. p. 419.

- ^ Sinclair, Doug (2010). "Ebenezer Ellinwood". DougSinclair.com.

- ^ Wicken (2002), p. 179.

- ^ Grenier (2008), p. 149

• MacMechan, Archibald (1931). "The Indian Terror". Red Snow on Grand Pré. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 163. - ^ Griffiths (2005), p. 390.

- ^ Zemel, Joel (2016). "A Mi'kmaq Declaration of War?". halifaxexplosion.net. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Chapman (2001), p. 23; Grenier (2008), p. 150

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 18.

- ^ a b Paul, Daniel N. "British Scalp Proclamation 1749". DanielPaul.com. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ Grenier (2008), p. 152; Salusbury (2011)

- ^ "A Complete Abstract of the English and French Navies". The London Magazine. Vol. 20. 1751. p. 341.

- ^ Brebner, John Bartlet (1927). New England's Outpost: Acadia Before the Conquest of Canada. Columbia University Press. p. 174. ISBN 9780231921282.

- ^ Faragher (2005), p. 262; Griffiths (2005), p. 392; Murdoch (1866), pp. 166–167; Grenier (2008), p. 153

- ^ Grenier (2008), pp. 154–155.

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 174.

- ^ Patterson, Frank H. (1917). A History of Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia. Royal Print & Litho. p. 19.

- ^ a b c Grenier (2008), p. 159.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Batard, Etienne". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Hand, p. 20[full citation needed]

- ^ Hand, p. 25[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Wilson (1751).

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 183.

- ^ Piers, Harry (1947). The Evolution of the Halifax Fortress, 1749–1928. Public Archives of Nova Scotia. p. 6. As cited in Landry (2007), p. 370

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 188.

- ^ a b More, James F. (1873). The History of Queens County, N.S. Halifax: Nova Scotia Printing Company. p. 202.

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 197.

- ^ Pichon, p.280

- ^ board of trade minutes Jan. 1750

- ^ Pothier, Bernard (1979). "du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, Louis". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

• Marshall (2011), p. 93

• Murdoch (1866), p. 310 - ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 191.

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 194.

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 201.

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 334.

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 27.

- ^ a b c Grenier (2008), p. 160.

- ^ a b Akins (1895), pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b Chapman (2001), p. 30.

- ^ Wilson (1751); Chapman (2001), p. 29

- ^ Faragher (2005), p. 272.

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 34.

- ^ a b c Murdoch (1866), p. 209.

- ^ a b Grenier (2008), p. 162.

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 40.

- ^ Section 3. No names for deaths. Deaths, Burials and Probate of Nova Scotians 1749–1799

- ^ Plank, Geoffrey (1998). "The Changing country of Anthony Casteel: Language, Religion, Geography, Political Loyalty, and Nationality in Mid-Eighteenth Century Nova Scotia". Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture. 27: 56, 58. doi:10.1353/sec.2010.0277. S2CID 143577353.

- ^ "The Monthly Chronologer". The London Magazine. 1753.

- ^ Plank, 1996, p.33-34[full citation needed]

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 138.

- ^ Whitehead, Ruth Holmes (1991). The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Micmac History, 1500–1950. Nimbus. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-921054-83-2.

- ^ Whitehead (1991), p. 137; (Murdoch 1866, p. 222)

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 219; Akins (1869)

- ^ Halifax Gazette, September 30, 1752[full citation needed]

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 209.

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 224.

- ^ Akins (1895), p. 28.

- ^ Wicken (2002), p. 188.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 136.

- ^ a b Bumsted, J. M. (2009). The Peoples of Canada: A Pre-Confederation History. Oxford University Press. p. 121-125. ISBN 978-0-19-543101-8.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 136; Akins (1895), p. 37

- ^ a b Patterson (1994), p. 137.

- ^ Webster, John Clarence (1933). The Career of the Abbe Le Loutre in Nova Scotia: With a Translation of His Autobiography. Private Printing.

- ^ a b Akins (1869), p. 208.

- ^ a b Bell (1961), p. 483, note 27.

- ^ Charles Morris. 1762. British Library, Manuscripts, Kings 205: Report of the State of the American Colonies. pp: 329–330;

• Akins (1895), p. 43 - ^ Faragher (2005), p. 271.

- ^ Faragher (2005), pp. 275, 290.

- ^ Faragher (2005), p. 277.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 139.

- ^ Faragher (2005), p. 291.

- ^ Baxter, James Phinney, ed. (1908). Documentary history of the state of Maine. Vol. Volume XII. Portland, Maine: Maine Historical Society.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Marshall (2011), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Bell (1961), p. 508.

- ^ Fisher, L.R. (1979). "Francklin, Michael". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ https://archive.org/details/historyoflifesuf00grac

- ^ Blakeley, Phyllis R. (1974). "Cobb, Silvanus". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Murdoch (1866), p. 258.

- ^ Nova Scotia Historical Society (1881)[page needed]

• Raddall, Thomas H. (1993) [1948]. Halifax, Warden of the North. Nimbus. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-55109-060-3.

• Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. Volume XII. Halifax: Nova Scotia Historical Society. 1905.{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

• Collection de manuscrits contenant lettres, mémoires, et autres documents historiques relatifs à la Nouvelle-France: recueillis aux archives de la province de Québec, ou copiés à l'étranger [Collection of manuscripts containing letters, memoirs, and other historical documents relating to New France: collected from the archives of the province of Quebec, or copied abroad] (in French). Vol. Vol. III. Québec: A. Côté. 1884.{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Williamson, William Durkee (1832). The History of the State of Maine: From Its First Discovery, 1602, to the Separation, A. D. 1820, Inclusive. Vol. Vol. II. Glazier, Masters & Company.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Campbell (2005), p. 29.

- ^ Hand, p. 102[full citation needed]

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 141.

- ^ a b Patterson (1994), p. 142.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 142; Patterson (1993), pp. 51–52

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 146.

- ^ Patterson (1994), p. 152.

Primary sources

- Akins, Thomas B., ed. (1869). Selections from the Public Documents of the Province of Nova Scotia: Pub. Under a Resolution of the House of Assembly Passed March 15, 1865. Halifax: Charles Annand. specifically Parts I: Papers Relating to the Acadian French (1714–1755) and Part III: Papers related to the French encroachment on Nova Scotia (1749–1754), and the War in North America (1754–1761)

- Du Boscq de Beaumont, Gaston (1899). Les Derniers Jours de l'Acadie (1748–1758): Correspondances et Mémoires; Extraits du Portefeuille de M. Le Courois de Surlaville... Paris: E. Lechevalier.

- Jefferys, Thomas (1754). The Conduct of the French, With Regard to Nova Scotia: From Its First Settlement to the Present Time ... London: T. Jefferys.

- Johnstone, Chevalier de (1866). "Campaign against Louisbourg 1750 – '58". Manuscripts Relating to the Early History of Canada. Second series. Literary and Historical Society of Quebec. Quebec: Middleton and Dawson.

- Lawrence, Charles (1953). Journal and letters of Colonel Charles Lawrence: being a day by day account of the founding of Lunenburg. Halifax: Public Archives of Nova Scotia.

- Salusbury, John (2011) [1982]. Ronald Rompkey (ed.). Expeditions of Honour: The Journal of John Salusbury in Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1749–53. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-9089-2.

- Wilson, John (1751). A Genuine Narrative of the Transactions in Nova Scotia since the Settlement, June 1749, till August the 5th, 1751: in which the nature, soil, and produce of the country are related, with the particular attempts of the Indians to disturb the colony. London: A. Henderson.

- Winslow, Joshua (1936). The Journal of Joshua Winslow, Recording His Participation in the Events of the Year 1750, Memorable in the History of Nova Scotia.

- An Account of the Present State of Nova-Scotia: in Two Letters to a Noble Lord: ... London. 1756.

- "Extract of a Letter from Halifax in Nova Scotia dated March 20, 1749–50". The London Magazine. Vol. 19. 1750. pp. 196–197.

Secondary sources

- Akins, Thomas B. (1895). History of Halifax City. Halifax: Nova Scotia Historical Society.

- Barnes, Thomas Garden (1996). "'Twelve Apostles' or a Dozen Traitors?: Acadian Collaborators during King George's War, 1744–8". In F. Murray Greenwood; Barry Wright (eds.). Law, Politics, and Security Measures, 1608–1837. Canadian State Trials. Vol. Volume I. Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, University of Toronto Press. pp. 98–113. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt1vgw6d9.10.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Bell, Winthrop Pickard (1961). The Foreign Protestants and the Settlement of Nova Scotia: The History of a Piece of Arrested British Colonial Policy in the Eighteenth Century. University of Toronto Press.

- Campbell, William Edgar (2005). The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec. New Brunswick Military Heritage Project. Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 978-0-86492-426-1.

- Carroll, Brian D. (September 2012). "'Savages' in the Service of Empire: Native American Soldiers in Gorham's Rangers, 1744-1762". New England Quarterly. 85 (3): 383–429. doi:10.1162/TNEQ_a_00207. S2CID 57559449.

- Chapman, Harry (2001). In the Wake of the Alderney: Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, 1750-2000. Dartmouth Historical Association. ISBN 978-1-55109-374-1.

- Douglas, W.A.B. (March 1966). "The Sea Militia of Nova Scotia, 1749-1755: A Comment on Naval Policy". Canadian Historical Review. 47 (1): 22–37. doi:10.3138/CHR-047-01-02. S2CID 162250099.

- Edwards, Joseph Plimsoll (1913). "The Militia of Nova Scotia, 1749–1867". Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. Volume XVII. Halifax: Wm. Macnab & Son. pp. 63–110.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W.W Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- Landry, Peter (2007). The Lion and the Lily. Trafford. ISBN 978-1-4251-5450-9.

- Marshall, Dianne (2011). Heroes of the Acadian Resistance: The Story of Joseph Beausoleil Broussard and Pierre II Surette 1702-1765. Formac. ISBN 978-0-88780-978-1.

- Murdoch, Beamish (1865). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. Vol. I. Halifax: J. Barnes.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Murdoch, Beamish (1866). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. Vol. II. Halifax: J. Barnes.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Patterson, Stephen E. (Autumn 1993). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749–61: A Study in Political Interaction". Acadiensis. 23 (1): 23–59. JSTOR 30303469.

- Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 125–155. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm.

- Sauvageau, Robert (1987). Acadie: la guerre de cent ans des français d'Amérique aux Maritimes et en Louisiane, 1670-1769. Berger-Levrault. ISBN 978-2-7013-0720-6.

- Wicken, William (2002). Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7665-6.

- Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society for the Years 1879-1880. Vol. Volume II. Halifax: Nova Scotia Historical Society. 1881.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

External links

- 1740s conflicts

- 1750s conflicts

- 1740s in North America

- 1750s in North America

- Military history of Acadia

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of New England

- Military history of the Thirteen Colonies

- Military history of Canada

- Acadian history

- Conflicts in Nova Scotia

- Indigenous conflicts in Canada

- Conflicts in Canada

- Second Hundred Years' War

- Wars involving Great Britain

- Wars involving France

- Wars involving the indigenous peoples of North America

- Mi'kmaq

- Colonial American and Indian wars

- Wabanaki Confederacy

- History of Halifax, Nova Scotia

- 18th century in Nova Scotia