Isabeau of Bavaria

| Isabeau of Bavaria | |

|---|---|

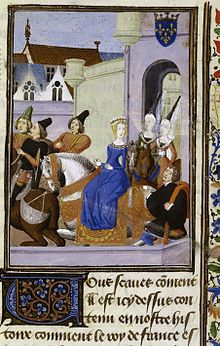

Queen Isabeau receiving Christine de Pizan's Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, c. 1410–1414. Illumination on parchment, British Library | |

| Queen consort of France | |

| Tenure | 17 July 1385 – 21 October 1422 |

| Coronation | 23 August 1389, Notre-Dame |

| Born | c. 1370 |

| Died | September 1435 Paris |

| Burial | October 1435[1] |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | House of Wittelsbach |

| Father | Stephen III, Duke of Bavaria |

| Mother | Taddea Visconti |

Isabeau of Bavaria (or Isabelle; also Elisabeth of Bavaria-Ingolstadt; c. 1370 – September 1435) was Queen of France as the wife of King Charles VI from 1385 to 1422. She was born into the House of Wittelsbach as the only daughter of Duke Stephen III of Bavaria-Ingolstadt and Taddea Visconti of Milan. At age 15 or 16, Isabeau was sent to France to marry the young Charles VI; the couple wed three days after their first meeting. Isabeau was honored in 1389 with a lavish coronation ceremony and entry into Paris.

In 1392, Charles suffered the first attack of what was to become a lifelong and progressive mental illness, resulting in periodic withdrawal from government. The episodes occurred with increasing frequency, leaving a court both divided by political factions and steeped in social extravagances. A 1393 masque for one of Isabeau's ladies-in-waiting—an event later known as Bal des Ardents—ended in disaster with Charles almost burning to death. Although the King demanded Isabeau's removal from his presence during his illness, he consistently allowed her to act on his behalf. In this way she became regent to the Dauphin of France (heir apparent), and sat on the regency council, allowing her far more power than was usual for a medieval queen.

Charles' illness created a power vacuum that eventually led to the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War between supporters of his brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans, and the royal dukes of Burgundy, Philip the Bold and John the Fearless. Isabeau shifted allegiances as she chose the most favorable paths for the heir to the throne. When she followed the Armagnacs, the Burgundians accused her of adultery with the Duke of Orléans; when she sided with the Burgundians, the Armagnacs removed her from Paris and she was imprisoned. In 1407, John the Fearless assassinated Orléans, sparking hostilities between the factions. The war ended soon after Isabeau's son Charles had John assassinated in 1419—an act that saw him disinherited. Isabeau attended the 1420 signing of the Treaty of Troyes, which decided that the English king should inherit the French crown after the death of her husband. She lived in English-occupied Paris until her death in 1435.

Isabeau was popularly seen as a spendthrift and irresponsible philanderess. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries historians re-examined the extensive chronicles of her lifetime, concluding that many unflattering elements of her reputation were unearned and stemmed from factionalism and propaganda.

Lineage and marriage

[edit]Isabeau's parents were Duke Stephen III of Bavaria-Ingolstadt and Taddea Visconti, the eldest child of Bernabò Visconti, Lord of Milan, who turned her over to Duke Stephen for a dowry of 100,000 ducats. During this period, Bavaria was counted among the most powerful German states, divided though it was at certain times among members of the House of Wittelsbach.[2] The Visconti family was anxious to cultivate political connections with the powerful Wittelsbachs, and three of Taddea's siblings also married members of various branches of the family. Isabeau was most likely born in Munich, where she was baptized as Elisabeth[note 1] at the Church of Our Lady.[2] Her notable Wittelsbach ancestors included her great-grandfather Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV.[3][note 2]

In 1383, Isabeau's uncle, Duke Frederick of Bavaria-Landshut, suggested that she be considered as a bride for King Charles VI of France. The match was proposed again at the lavish Burgundian double wedding in Cambrai in April 1385. At this event, John, Count of Nevers (who became known as John the Fearless after he succeeded his father Philip the Bold as duke of Burgundy in 1404) married Margaret of Bavaria, whereas John's sister, Margaret of Burgundy, married Duke William II of Bavaria-Straubing, one of the brothers of Margaret of Bavaria. Charles, then 17, rode in the tourneys at the wedding. He was an attractive, physically fit young man who enjoyed jousting and hunting and was anxious to be married.[4]

As part of his duties as a member of the regency council that governed France during the minority of Charles VI, the king's uncle, Philip the Bold, thought that the proposed marriage to Isabeau would be an ideal means to build an alliance with the Holy Roman Empire in opposition to the crown of England.[5] Isabeau's father reluctantly agreed to the plan and sent her to France with his brother Frederick on the pretext of taking a pilgrimage to Amiens, whose Cathedral housed a celebrated relic of the time (the reputed head of John the Baptist).[3] He was adamant that she was not to know that she was being sent to France to be examined as a prospective bride for Charles[5] and refused permission for her to be examined in the nude, as was customary at the time.[2] According to the contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart, Isabeau was 13 or 14 when the match was proposed and about 16 at the time of the marriage in 1385, suggesting a birth date of around 1370.[3]

Before her presentation to Charles, Isabeau visited Hainaut for about a month, staying with her granduncle Duke Albert I, Count of Holland, who also ruled part of the hereditary Wittelsbach territories of Bavaria-Straubing. Albert's wife, Margaret of Brieg, had Isabeau discard her Bavarian style of dress, which would have been deemed unsuitable as courtly attire in France, and taught her etiquette suitable for the French court. She learned quickly, suggestive of an intelligent and quick-witted character.[6] On 13 July 1385, she traveled to Amiens to be presented to Charles.[7]

Froissart writes of the meeting in his Chronicles, saying that Isabeau stood motionless while being inspected, exhibiting perfect behavior by the standards of her time. Arrangements were made for the two to be married in Arras, but on the first meeting, Charles felt "happiness and love enter his heart, for he saw that she was beautiful and young, and thus he greatly desired to gaze at her and possess her".[8] She did not yet speak French and may not have reflected the idealized beauty of the period, perhaps inheriting her mother's dark Italian features, which were considered unfashionable at the time. Nonetheless, Charles and Isabeau were married just three days later.[7] Froissart documented the royal wedding with jokes about the lascivious guests at the feast and the "hot young couple".[9]

Charles seemingly loved his young wife, and he lavished gifts on her. On the occasion of their first New Year in 1386, he gave her a red velvet palfrey saddle trimmed with copper and decorated with an intertwined K and E (for Karol and Elisabeth), and he continued to give her gifts of rings, tableware and clothing.[7] The king's uncles were apparently also pleased with the match, which contemporary chroniclers, notably Froissart and Michel Pintoin (the Monk of St. Denis), describe similarly as a match rooted in desire aroused by Isabeau's beauty. The day after the wedding, Charles departed for a military campaign against the English, whereas Isabeau traveled to Creil to live with his step-great-grandmother, Queen Dowager Blanche, who taught her courtly traditions. In September, she took up residence at the Château de Vincennes, where, in the early years of their marriage, Charles frequently joined her. It soon became her favorite home.[6]

Coronation

[edit]Isabeau's coronation was celebrated on 23 August 1389 with a lavish ceremonial entry into Paris. The noblewomen in the coronation procession were dressed in lavish costumes with thread-of-gold embroidery and rode in litters escorted by knights. Philip the Bold wore a doublet embroidered with 40 sheep and 40 swans, each decorated with a bell made of pearls.[10]

The procession lasted from morning to night. The streets were lined with tableaux vivants. More than a thousand burghers stood along the route; those on one side were dressed in green facing, those on the opposite in red. The procession began at the Porte de St. Denis and passed under a canopy of sky-blue cloth beneath which children dressed as angels sang, winding into the Rue Saint-Denis before arriving at the Notre Dame for the coronation ceremony.[10] As Tuchman describes the event, "So many wonders were to be seen and admired that it was evening before the procession crossed the bridge leading to Notre Dame and the climactic display."[11]

As Isabeau crossed the Grand Pont to Notre Dame, a person dressed as an angel descended from the church by mechanical means and "passed through an opening of the hangings of blue taffeta with golden fleurs-des-lis, which covered the bridge, and put a crown on her head." The angel was then pulled back up into the church.[12] An acrobat carrying two candles walked along a rope suspended from the spires of the cathedral to the tallest house in the city.[10]

After Isabeau's crowning, the procession made its way back from the cathedral along a route lit by 500 candles. They were greeted by a royal feast and a progression of narrative pageants, complete with a depiction of the Fall of Troy. Isabeau, then seven months pregnant, nearly fainted from heat on the first of the five days of festivities. To pay for the extravagant event, taxes were raised in Paris two months later.[10]

The illness of Charles VI

[edit]

In 1392, Charles suffered the first of what was to become a lifelong series of bouts of insanity when, on a hot August day outside Le Mans, he attacked his retinue, including his brother Orléans, killing four men.[13] After the attack he fell into a coma that lasted four days. Few believed he would recover. His uncles, the dukes of Burgundy and Berry, took advantage of his illness to seize power quickly by re-establishing themselves as regents and dissolving the so-called Marmouset council, a group of clerics and lesser nobles who had advised Charles V. The uncles of Charles VI ruled France as members of a regency council during his minority between 1380 and 1388. The Marmousets then returned as royal counselors until Charles VI became ill.[14]

The King's sudden onset of insanity was seen by some as a sign of divine anger and punishment and by others as the result of magic.[14] Modern historians speculate that he may have suffered from the onset of paranoid schizophrenia.[15] The comatose king was returned to Le Mans, where Guillaume de Harsigny—a venerable 92-year-old physician—was summoned to treat him. Charles regained consciousness and his fever subsided; he was gradually returned to Paris in September.[14]

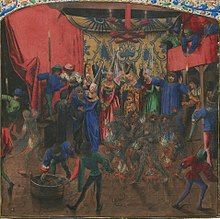

Harsigny recommended a program of amusements to assist the king's recovery. A member of the court suggested that Charles surprise Isabeau and the other ladies by joining a group of courtiers who would disguise themselves as wild men and invade the masquerade celebrating the remarriage of Isabeau's lady-in-waiting, Catherine de Fastaverin. This came to be known as the Bal des Ardents ("The Ball of the Burning Men"). Charles was almost killed and four of the dancers burned to death when a spark from a torch brought by the duke of Orléans (the king's brother) lit one of the dancer's costumes on fire. The disaster undermined confidence in king's capacity to rule. Parisians considered it proof of courtly decadence and threatened to rebel against the more powerful members of the nobility. The public's outrage forced the King and the duke of Orléans, whom a contemporary chronicler accused of attempted regicide and sorcery, into offering penance for the event.[16]

Charles suffered a second and more prolonged attack of insanity the following June; it removed him from his duties for about six months and set a pattern that would hold for the next three decades as his condition deteriorated.[17] Froissart described the bouts of illness as so severe that the King was "far out of the way; no medicine could help him",[18] although he had recovered from the first attack within months.[19] For the first 20 years of his illness, he experienced sustained periods of lucidity to the extent that he could continue to rule. Suggestions were made to replace him with a regent, although there was uncertainty and debate as to whether a regency could assume the full role of a living monarch.[19] When he was incapable of ruling, his brother, the duke of Orléans, and their cousin John the Fearless, duke of Burgundy, were chief among those who sought to take control of the government.[17]

When Charles became ill in the 1390s, Isabeau was 22; she had three children remaining to her after losing two infants (seven more would be born up to 1407, of whom only the last one failed to survive early childhood).[20] During the worst of his illness, Charles was unable to recognize her and caused her great distress by demanding her removal when she entered his chamber.[7] The Monk of St Denis wrote in his chronicle, "What distressed her above all was to see how on all occasions ... the king repulsed her, whispering to his people, 'Who is this woman obstructing my view? Find out what she wants and stop her from annoying and bothering me.'"[21] As his illness worsened at the turn of the century, she was accused of abandoning him, particularly when she moved her residence to the Hôtel Barbette. Historian Rachel Gibbons speculates that Isabeau wanted to distance herself from her husband and his illness, writing, "it would be unjust to blame her if she did not want to live with a madman."[22]

Since the King often did not recognize her during his psychotic episodes and was upset by her presence, it was eventually deemed advisable to provide him with a mistress, Odette de Champdivers, the daughter of a horse-dealer. According to Tuchman, Odette is said to have resembled Isabeau and was called "the little Queen".[23] She had probably assumed this role by 1405 with Isabeau's consent,[24] but during his remissions, the King still had sexual relations with his wife, whose last pregnancy occurred in 1407. Records show that Isabeau was in the King's chamber on 23 November 1407, the night of the assassination of the duke of Orléans, and again in 1408.[25]

The King's bouts of illness continued unabated until his death. He and Isabeau may have still felt mutual affection, and Isabeau exchanged gifts and letters with him during his periods of lucidity, but she distanced herself during the prolonged attacks of insanity. Historian Tracy Adams writes that Isabeau's attachment and loyalty is evident in the great efforts she made to retain the crown for his heirs in the ensuing decades.[26]

Court intrigues of the 1380s and 1390s

[edit]Isabeau's movements and political activities are well documented after the time of her marriage, partially because of the unusual positions of power she occupied as a result of her husband's recurring illnesses. Nevertheless, not much is known about her personal characteristics - historians even disagree about her appearance. She is variously described as "small and brunette" or "tall and blonde"; contemporaneous evidence is contradictory—chroniclers said of her either that she was "beautiful and hypnotic, or so obese through dropsy that she was crippled."[20][note 3] Despite her continuous residence in France from the time of her marriage as a teenager, she spoke with a heavy German accent that never diminished. Tuchman describes this as giving her an "alien" cast at the French court.[23] Tracy Adams describes Isabeau as a talented diplomat who navigated court politics with ease, grace and charisma.[27]

Charles VI attained sole control of the monarchy when was crowned King in 1387 at the age of 20. His first acts included the dismissal of his uncles who had been acting as regents and the reinstatement of the so-called Marmousets—a group of clerics and lesser nobles who had served as councilors to his father, Charles V. Additionally, he gave his brother, the duke of Orléans, more responsibility in affairs of state. Some years later, after the King's first attack of illness, tensions mounted between the duke of Orléans and the three royal uncles: Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy; John, Duke of Berry; and Louis II, Duke of Bourbon. Forced to assume a greater role in maintaining peace amidst the growing power struggle, which was to persist for many years, Isabeau succeeded in her role as peacekeeper among the various court factions.[27]

As early as the late 1380s and early 1390s, Isabeau demonstrated that she possessed diplomatic influence when the Florentine delegation requested her political intervention in the Gian Galeazzo Visconti affair.[note 4] The duke of Orléans, who was married to Gian Galeazzo's daughter Valentina, formed a pro-Visconti faction at court in alliance with the Duke of Burgundy. An anti-Visconti faction formed in opposition to them that included Isabeau, her brother Louis VII, Duke of Bavaria, and John III, Count of Armagnac. At that time, Isabeau lacked the political power to effect change. Some years later, however, at the 1396 wedding of her seven-year-old daughter Isabella to Richard II of England, Isabeau successfully negotiated an alliance between France and Florence with the Florentine ambassador Buonaccorso Pitti.[note 5][28]

In the 1390s, Jean Gerson, later the Chancellor of the University of Paris, formed a council to eliminate the Western Schism, and in recognition of her negotiating skills, he placed Isabeau on the council. The French wanted both the Avignon and Roman popes to abdicate in favor of a single papacy in Rome; Clement VII in Avignon welcomed Isabeau's presence given her record as an effective mediator. However, the effort faded when Clement VII died in 1394.[27]

During his short-lived recovery in the 1390s, Charles made arrangements for Isabeau to be "principal guardian of the Dauphin", their son, until he reached 13 years of age, giving her additional political power on the regency council.[20] Charles appointed Isabeau co-guardian of their children in 1393, a position shared with the royal dukes and her brother, Louis of Bavaria, while he gave Orléans full power of the regency.[29] In appointing Isabeau, Charles acted under laws enacted by his father, Charles V, which gave the Queen full power to protect and educate the heir to the throne.[30] These appointments separated power between Orléans and the royal uncles, increasing ill-will among the factions.[29] The following year, as Charles' bouts of illness became more severe and prolonged, Isabeau became the leader of the regency council, giving her power over the royal dukes and the Constable of France, while at the same time making her vulnerable to attack from various court factions.[20]

Political crises in France at the start of the 15th century

[edit]During Charles' illness, Orléans became financially powerful as the official tax collector,[31] and in the following decade Isabeau and Orléans agreed to raise the level of taxation.[25] In 1401, during one of the King's absences, Orléans installed his own men to collect royal revenues, angering Philip the Bold who in retaliation raised an army, threatening to enter Paris with 600 men-at-arms and 60 knights. At that time Isabeau intervened between Orléans and Burgundy, preventing bloodshed and the outbreak of civil war.[31]

Charles trusted Isabeau enough by 1402 to allow her to arbitrate the growing dispute between the Orléanists and Burgundians, and he turned control of the treasury over to her.[20][32] After Philip the Bold died in 1404 and his son John the Fearless became Duke of Burgundy, the new duke continued the political strife in an attempt to gain access to the royal treasury for Burgundian interests. Orléans and the royal dukes thought John was usurping power for his own interests and Isabeau, at that time, aligned herself with Orléans to protect the interests of the crown and her children. Furthermore, she distrusted John the Fearless who she thought overstepped himself in rank—he was cousin to the King, whereas Orléans was Charles' brother.[32]

Rumors that Isabeau and Orléans were lovers began to circulate, a relationship that was considered incestuous. Whether the two were intimate has been questioned by contemporary historians, including Gibbons who believes the rumor may have been planted as propaganda against Isabeau as retaliation against tax increases she and Orléans ordered in 1405.[7][25] An Augustinian friar, Jacques Legrand (writer), preached a long sermon to the court denouncing excess and depravity, in particular mentioning Isabeau and her habit of wearing clothing with exposed necks, shoulders and décolletage.[33] The monk presented his sermon as allegory so as not to offend Isabeau overtly, but he cast her and her ladies-in-waiting as "furious, vengeful characters". He said to Isabeau, "If you don't believe me, go out into the city disguised as a poor woman, and you will hear what everyone is saying." Thus he accused Isabeau as having lost touch with the commoners and the court with its subjects.[34] At about the same time, a satirical political pamphlet called Songe Veritable, now considered by historians to be pro-Burgundian propaganda, was released and widely distributed in Paris. The pamphlet hinted at the Queen's relations with Orléans.[33]

John the Fearless accused Isabeau and Orléans of fiscal mismanagement and again demanded money for himself, in recompense for the loss of royal revenues after his father's death;[35] an estimated half of Philip the Bold's revenues had come from the French treasury.[17] John raised a force of 1,000 knights and entered Paris in 1405. Orléans hastily retreated with Isabeau to the fortified castle of Melun, with her household and children a day or so behind. John immediately left in pursuit, intercepting the party of chaperones and royal children. He took possession of the Dauphin, and returned him to Paris under control of Burgundian forces; however, the boy's uncle, the duke of Berry, quickly took control of the child at the orders of the Royal Council. At that time, Charles was lucid for about a month and able to help with the crisis.[35] The incident, that came to be known as the enlèvement of the dauphin, almost caused full-scale war, but it was averted.[36] Orléans quickly raised an army while John encouraged Parisians to revolt. They refused, claiming loyalty to the King and his son; Berry was made captain general of Paris and the city's gates were locked. In October, Isabeau became active in mediating the dispute in response to a letter from Christine de Pizan and an ordinance from the Royal Council.[37]

The assassination of the Duke of Orléans and aftermath

[edit]

In 1407, John the Fearless ordered Orléans' assassination.[38] On 23 November,[39] hired killers attacked the duke as he returned to his Paris residence, cut off his hand holding the horse's reins, and "hacked [him] to death with swords, axes, and wooden clubs". His body was left in a gutter.[40] John first denied involvement in the assassination,[38] but quickly admitted that the act was done for the Queen's honor, claiming he acted to "avenge" the monarchy of the alleged adultery between Isabeau and Orléans.[41] His royal uncles, shocked at his confession, forced him to leave Paris while the Royal Council attempted a reconciliation between the Houses of Burgundy and Orléans.[38]

In March 1408, Jean Petit presented a lengthy and well-attended justification at the royal palace before a large courtly audience.[42] Petit argued convincingly that in the King's absence Orléans had become a tyrant,[43] practiced sorcery and necromancy, was driven by greed, and had planned to commit fratricide at the Bal des Ardents. Petit then argued that John should be exonerated because he had defended the King and monarchy by assassinating Orléans.[44] Charles, "insane during the oration", was convinced by Petit's argument and pardoned John the Fearless, only to rescind the pardon in September.[42]

Violence again broke out after the assassination; Isabeau had troops patrol Paris and, to protect the Dauphin Louis, Duke of Guyenne, she again left the city for Melun. In August she staged an entry to Paris for the Dauphin, and early in the new year, Charles signed an ordinance giving the 13-year-old the power to rule in the Queen's absence. During these years, Isabeau's greatest concern was the Dauphin's safety as she prepared him to take up the duties of the King; she formed alliances to further those aims.[42] At this point, the Queen and her influence were still crucial to the power struggle. Physical control of Isabeau and her children became important to both parties and she was frequently forced to change sides, for which she was criticized and called unstable.[20] She joined the Burgundians from 1409 to 1413, then switched sides to form an alliance with the Orléanists from 1413 to 1415.[42]

At the Peace of Chartres in March 1409, John the Fearless was reinstated to the Royal Council after a public reconciliation with Orléans' son, Charles, Duke of Orléans, at Chartres Cathedral, although the feuding continued. In December that year, Isabeau bestowed the tutelle (guardianship of the Dauphin)[38] upon John the Fearless, made him the master of Paris, and allowed him to mentor the Dauphin,[45] after he had Jehan de Montagu, Grand Master of the King's household, executed. At that point, the Duke essentially controlled the Dauphin and Paris and was popular in the city because of his opposition to taxes levied by Isabeau and Orléans.[46] Isabeau's actions with respect to John the Fearless angered the Armagnacs, who in the fall of 1410 marched to Paris to "rescue" the Dauphin from the Duke's influence. At that time, members of the University of Paris, Jean Gerson in particular, proposed that all feuding members of the Royal Council step down and be immediately removed from power.[45]

To defuse tension with the Burgundians, a second double marriage was arranged in 1409. Isabeau's daughter Michelle married Philip the Good, son of John the Fearless; Isabeau's son, the Dauphin Louis, married John's daughter Margaret. Before the wedding, Isabeau negotiated a treaty with John the Fearless in which she clearly defined family hierarchy and her position in relation to the throne.[32][note 6]

Civil war

[edit]

Despite Isabeau's efforts to keep the peace, the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War broke out in 1411. John gained the upper hand during the first year, but the Dauphin began to build a power base; Christine de Pizan wrote of him that he was the savior of France. Still only 15, he lacked the power or backing to defeat John, who fomented revolt in Paris. In retaliation against the actions of John the Fearless, Charles of Orléans denied funds from the royal treasury to all members of the royal family. In 1414, instead of allowing her son, then 17, to lead, Isabeau allied herself with Charles of Orléans. The Dauphin, in return, changed allegiance and joined John, which Isabeau considered unwise and dangerous. The result was continued civil war in Paris.[42] Parisian commoners joined forces with John the Fearless in the Cabochien Revolt, and at the height of the revolt, a group of butchers entered Isabeau's home in search of traitors, arresting and taking away up to 15 of her ladies-in-waiting.[47] In his chronicles, Pintoin wrote that Isabeau was firmly allied with the Orléanists and the 60,000 Armagnacs who invaded Paris and Picardy.[48]

King Henry V of England took advantage of the internal strife in France, invading the northwest coast, and in 1415, he delivered a crushing defeat to the French at Agincourt.[49] Nearly an entire generation of military leaders died or were taken prisoner in a single day. John, still feuding with the royal family and the Armagnacs, remained neutral as Henry V went on to conquer towns in northern France.[49]

In December 1415, Dauphin Louis died suddenly at age 18 of illness, leaving Isabeau's political status unclear. Her 17-year-old fourth-born son, John of Touraine, now the Dauphin, had been raised since childhood in the household of Duke William II of Bavaria in Hainaut. Married to Countess Jacqueline of Hainaut, Dauphin John was a Burgundian sympathizer. William of Bavaria refused to send him to Paris during a period of upheaval as Burgundians plundered the city and Parisians revolted against another wave of tax increases initiated by Count Bernard VII of Armagnac; in a period of lucidity, Charles had raised the Count to be the Constable of France. Isabeau attempted to intervene by arranging a meeting with Jacqueline in 1416, but Armagnac refused to allow Isabeau to reconcile with the House of Burgundy, while William II continued to prevent the young Dauphin from entering Paris.[50]

In 1417, Henry V invaded Normandy with 40,000 men. Later that year, in April, Dauphin John died and another shift in power occurred when Isabeau's sixth and last son, Charles, age 14, became Dauphin. He was betrothed to Armagnac's daughter Marie of Anjou and favored the Armagnacs. At that time, Armagnac imprisoned Isabeau in Tours, confiscating her personal property (clothing, jewels and money), dismantling her household, and separating her from the younger children as well as her ladies-in-waiting. She secured her freedom in November with the help of the Duke of Burgundy. Accounts of her release vary: Monstrelet writes that Burgundy "delivered" her to Troyes, and Pintoin that the Duke negotiated Isabeau's release to gain control of her authority.[50] Isabeau maintained her alliance with Burgundy from that period until the Treaty of Troyes in 1420.[20]

Isabeau at first assumed the role of sole regent but in January 1418 yielded her position to John the Fearless. Together Isabeau and John abolished parliament (Chambre des comptes) and turned to securing control of Paris and the King. John took control of Paris by force on 28 May 1418, slaughtering Armagnacs. The Dauphin fled the city. According to Pintoin's chronicle, the Dauphin refused Isabeau's invitation to join her in an entry to Paris. She entered the city with John on 14 July.[51]

Shortly after he assumed the title of Dauphin, Charles negotiated a truce with John in Pouilly. Charles then requested a private meeting with John, on 10 September 1419 at a bridge in Montereau, promising his personal guarantee of protection. The meeting, however, was a ploy to assassinate John, whom Charles "hacked to death" on the bridge. His father, King Charles, immediately disinherited his son. The civil war ended after John's death.[52] The Dauphin's actions fueled more rumor about his legitimacy, and his disinheritance set the stage for the Treaty of Troyes.[20]

The Treaty of Troyes and Isabeau's later years

[edit]

By 1419, Henry V had occupied much of Normandy and demanded an oath of allegiance from the residents. The new Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, allied with the English, putting enormous pressure on France and Isabeau, who remained loyal to the King. In 1420, Henry sent an emissary to confer with the Queen, after which, according to Adams, Isabeau "ceded to what must have been a persuasively posed argument by Henry V's messenger".[53] France had effectively been left without an heir to the throne, even before the Treaty of Troyes. Charles VI had disinherited the Dauphin, whom he considered responsible for "breaking the peace for his involvement in the assassination of the duke of Burgundy"; he wrote in 1420 of the Dauphin that he had "rendered himself unworthy to succeed to the throne or any other title".[54] Charles of Orléans, next in line as heir under Salic law, had been taken prisoner at the Battle of Agincourt and was kept in captivity in London.[49][55]

In the absence of an official heir to the throne, Isabeau accompanied King Charles to sign the Treaty of Troyes in May 1420. Gibbons writes that the treaty "only confirmed [the Dauphin's] outlaw status."[54] The King's illness prevented him from appearing at the signing of the treaty, forcing Isabeau to stand in for him; which, according to Gibbons, gave her "perpetual responsibility in having sworn away France".[54] For many centuries, Isabeau stood accused of relinquishing the crown because of the Treaty.[20] Under the terms of the Treaty, Charles remained as King of France but Henry V, who married Charles' and Isabeau's daughter, Catherine, was allowed to keep control of the territories he conquered in Normandy and was to be Charles' successor, governing France with the Duke of Burgundy.[56] Isabeau was to live in English-controlled Paris.[53]

Charles VI died in October 1422. As Henry V had died earlier the same year, his infant son by Catherine, Henry VI, was proclaimed King of France according to the terms of the Treaty of Troyes, with the Duke of Bedford acting as regent.[56] Rumors circulated about Isabeau again; some chronicles describe her living in a "degraded state".[53] According to Tuchman, Isabeau had a farmhouse built in St. Ouen where she looked after livestock, and in her later years, during a lucid episode, Charles arrested one of her lovers whom he tortured, then drowned in the Seine.[57] Desmond Seward writes it was the disinherited Dauphin who had the man killed. Described as a former lover of Isabeau as well as a "poisoner and wife-murderer", Charles kept him as a favorite at his court until ordering his drowning.[58]

Rumors about Isabeau's promiscuity flourished, which Adams attributes to English propaganda intended to secure England's grasp on the throne. An allegorical pamphlet, called Pastorelet, was published in the mid-1420s painting Isabeau and Orleans as lovers.[59] During the same period, Isabeau was contrasted with Joan of Arc, considered virginally pure, in the allegedly popular saying "Even as France had been lost by a woman it would be saved by a woman". Adams writes that Joan of Arc has been attributed with the words "France, having been lost by a woman, would be restored by a virgin", but neither saying can be substantiated by contemporary documentation or chronicles.[60]

In 1429, when Isabeau lived in English-occupied Paris, the accusation was again put forth that Charles VII was not the son of Charles VI. At that time, with two contenders for the French throne—the young Henry VI and disinherited Charles—this could have been propaganda to prop up the English claim. Furthermore, gossip spread that Joan of Arc was Isabeau and Orleans' illegitimate daughter—a rumor Gibbons finds improbable because Joan of Arc almost certainly was not born for some years after Orléans' assassination. Stories circulated that the dauphins were murdered, and attempts were made to poison the other children, all of which added to Isabeau's reputation of one of history's great villains.[55]

Isabeau was removed from political influence and retired to live in the Hôtel Saint-Pol with her brother's second wife, Catherine of Alençon. She was accompanied by her ladies-in-waiting Amelie von Orthenburg and Madame de Moy, the latter of whom had traveled from Germany and had stayed with her as dame d'honneur since 1409. Isabeau possibly died there in late September 1435.[53] Her death and funeral were documented by Jean Chartier (member of St Denis Abbey), who may well have been an eyewitness.[55]

Reputation and legacy

[edit]Isabeau was dismissed by historians in the past as a wanton, weak and indecisive leader. Modern historians now see her as taking an unusually active leadership role for a queen of her period, forced to take responsibility as a direct result of Charles' illness. Her critics accepted skewed interpretations of her role in the negotiations with England, resulting in the Treaty of Troyes, and in the rumors of her marital infidelity with Orléans.[61] Gibbons writes that a queen's duty was to secure the succession to the crown and look after her husband; historians described Isabeau as having failed in both respects.[7] Gibbons goes on to say that even her physical appearance is uncertain; depictions of her vary depending on whether she was to be portrayed as good or evil.[62]

Rumored to be a bad mother, she was accused of "incest, moral corruption, treason, avarice and profligacy ... political aspirations and involvements".[63] Adams writes that historians reassessed her reputation in the late 20th century, exonerating her of many of the accusations, seen particularly in Gibbons' scholarship. Furthermore, Adams admits she believed the allegations against Isabeau until she delved into contemporary chronicles: there she found little evidence against the Queen except that many of the rumors came from only a few passages, and in particular from Pintoin's pro-Burgundian writing.[64]

After the onset of the King's illness, a common belief was that Charles' mental illness and inability to rule were due to Isabeau's witchcraft; as early as the 1380s, rumors spread that the court was steeped in sorcery. In 1397 Orléans' wife, Valentina Visconti, was forced to leave Paris because she was accused of using magic.[65] The court of the "mad king" attracted magicians with promises of cures who were often used as political tools by the various factions. Lists of people accused of bewitching Charles were compiled, with Isabeau and Orléans both listed.[66]

The accusations of adultery were rampant. According to Pintoin's chronicle, "[Orléans] clung a bit too closely to his sister-in-law, the young and pretty Isabeau of Bavaria, the queen. This ardent brunette was twenty-two; her husband was insane and her seductive brother-in-law loved to dance, beyond that we can imagine all sorts of things".[67] Pintoin said of the Queen and Orléans that they neglected Charles, behaved scandalously and "lived on the delights of the flesh",[68] spending large amounts of money on court entertainment.[25] The alleged affair, however, is based on a single paragraph from Pintoin's chronicles, according to Adams, and is no longer considered proof.[69]

Isabeau was accused of indulging in extravagant and expensive fashions, jewel-laden dresses and elaborate braided hairstyles coiled into tall shells, covered with wide double hennins that, reportedly, required widened doorways to pass through.[70] In 1406, a pro-Burgundian satirical pamphlet in verse allegory listed Isabeau's supposed lovers.[33] She was accused of leading France into a civil war because of her inability to support a single faction; she was described as an "empty headed" German; of her children, it was said that she "took pleasure in a new pregnancy only insofar as it offered her new gifts"; and her political mistakes were attributed to her being fat.[67]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, historians characterized Isabeau as "an adulterous, luxurious, meddlesome, scheming, and spendthrift queen", overlooking her political achievements and influence. A popular book written by Louise de Karalio (1758–1822) about the "bad" French queens prior to Marie Antoinette is, according to Adams, where "Isabeau's black legend attains its full expression in a violent attack on the French royalty in general and queens in particular."[71] Karalio wrote: "Isabeau was raised by the furies to bring about the ruin of the state and to sell it to its enemies; Isabeau of Bavaria appeared, and her marriage, celebrated in Amiens on 17 July 1385, would be regarded as the most horrifying moment in our history".[72] Isabeau was painted as Orléans' passionate lover, and the inspiration for the Marquis de Sade's unpublished 1813 novel Histoire secrète d'Isabelle de Bavière, reine de France, about which Adams writes, "submitting the queen to his ideology of gallantry, [the Marquis de Sade] gives her rapaciousness a cold and calculating violence ... a woman who carefully manages her greed for maximum gratification."[73] She goes on to say that de Sade admitted to "being perfectly aware that the charges against the queen are without ground."[74]

Patronage

[edit]

Like many of the Valois, Isabeau was an appreciative art collector. She loved jewels and was responsible for the commissions of particularly lavish pieces of ronde-bosse — a newly developed technique of making enamel-covered gold pieces. Documentation suggests she commissioned several fine pieces of tableaux d'or from Parisian goldsmiths.[76]

In 1404, Isabeau gave Charles a spectacular ronde-bosse, known as the Little Golden Horse Shrine, (or Goldenes Rössl), now part of the treasure of the Marian shrine of Altötting, Bavaria.[note 7] Contemporary documents identify the statuette as a New Year's gift—an étrennes—a Roman custom Charles revived to establish rank and alliances during the period of factionalism and war. With the exception of manuscripts, the Little Golden Horse is the single surviving documented étrennes of the period. Weighing 26 pounds (12 kg), the gold piece is encrusted with rubies, sapphires and pearls. It depicts Charles kneeling on a platform above a double set of stairs, presenting himself to the Virgin Mary and child Jesus, who are attended by John the Evangelist and John the Baptist. A jewel encrusted trellis or bower is above; beneath stands a squire holding the golden horse.[77][78] Isabeau also exchanged New Year's gifts with the Duke of Berry; one extant piece is the ronde-bosse statuette Saint Catherine.[76]

Medieval author Christine de Pizan solicited the Queen's patronage at least three times. In 1402, she sent a compilation of her literary argument Querelle du Roman de la Rose—in which she questions the concept of courtly love—with a letter exclaiming "I am firmly convinced the feminine cause is worthy of defense. This I do here and have done with my other works." In 1410 and again in 1411, Pizan solicited the Queen, presenting her in 1414 an illuminated copy of her works.[79] In The Book of the City of Ladies, Pizan praised Isabeau lavishly, and again in the illuminated collection, The Letter of Othea, which scholar Karen Green believes for de Pizan is "the culmination of fifteen years of service during which Christine formulated an ideology that supported Isabeau's right to rule as regent in this time of crisis."[80]

Isabeau showed great piety, essential for a queen of her period. During her lifetime, and in her will, she bequeathed property and personal possessions to Notre Dame, St. Denis, and the convent in Poissy.[81]

Children

[edit]The birth of each of Isabeau's 12 children is well chronicled;[20] even the decoration schemes of the rooms in which she gave birth are described.[81] She had six sons and six daughters. The first son, born in 1386, died as an infant and the last, Philip, born in 1407, lived a single day. Three others died young with only her youngest son, Charles VII, living to adulthood. Five of the six daughters survived; four were married and one, Marie (1393–1438), was sent at age four to be raised in a convent, where she became prioress.[81]

Her first son, Charles (b. 1386), the first Dauphin, died in infancy. A daughter, Joan, born two years later, lived until 1390. The second daughter, Isabella (1389-1409) was married at age seven to Richard II of England and after his death to Charles, Duke of Orléans. The third daughter, another Joan (1391–1433), who lived to age 42, married John VI, Duke of Brittany. The fourth daughter, Michelle (1395–1422), first wife to Philip the Good, died childless at age 27. Catherine of Valois, Queen of England (1401–1437), married Henry V of England; on his death she took Sir Owen Tudor as her second husband.[81]

Of her remaining sons, the second Dauphin was another Charles (1392–1401), who died at age eight of a "wasting illness". Louis, Duke of Guyenne (1397-1415), was the third Dauphin, married to Margaret of Nevers, who died at age 18. John, Duke of Touraine (1398-1417), the fourth Dauphin, the first husband of Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut, died without issue, also at the age of 18. The fifth Dauphin, yet another Charles (1403-1461), became King Charles VII of France after his father's death. He was married to Marie of Anjou.[81] Her last son, Philip, died in infancy in the year 1407.

According to modern historians, Isabeau stayed in close proximity to the children during their childhood, had them travel with her, bought them gifts, wrote letters, bought devotional texts, and arranged for her daughters to be educated. She resisted separation and reacted against having her sons sent to other households to live (as was the custom at the time). Pintoin records that she was dismayed at the marriage contract that stipulated her third surviving son, John, be sent to live in Hainaut. She maintained relationships with her daughters after their marriages, writing letters to them frequently.[81] She sent them out of Paris during an outbreak of plague, staying behind herself with the youngest infant, John, too young to travel. The Celestines allowed "whenever and as often as she liked, she and her children could enter the monastery and church ... their vineyards and gardens, both for devotion and for entertainment and pleasure of herself and her children."[82]

-

Miniature from a late 15th-century manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles showing Isabella's marriage to Richard II of England

-

Joan of France, shown in a late 17th-century or early 18th-century drawing, married John VI, Duke of Brittany

-

Michelle of Valois, shown here in a white hennin (from the center panel of a Flemish triptych), was first wife to Philip the Good

-

Catherine of Valois, meeting Henry V of England, shown in a 19th-century woodcut, printed by Edmund Evans

-

Charles VII of France shown in a mid-15th-century portrait by Jean Fouquet

-

Issue of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Isabeau of Bavaria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Called Elisabeth until her marriage, Gibbons says she started using the name Isabeau probably soon after becoming queen of France. See Gibbons, 53. Famiglietti writes that she signed letters in French as "Ysabel", transformed first to "Ysabeau" and then "Isabeau" in the 15th century. See Famiglietti, 190

- ^ Gibbons writes of Isabeau, "she was not quite the 'nobody' that had been suggested ... it is clear that Charles V himself saw the Wittelsbach clan as useful potential allies in the continuing war with England." See Gibbons, 52

- ^ Historian Tracy Adams speculates that the depiction of obesity might stem from a mistranslation saying the Queen bore a heavy burden, which Adams believes refers to the heavy burden Isabeau assumed because of Charles' illness. See Adams, 224

- ^ He had deposed and murdered Isabeau's maternal grandfather Bernabò Visconti of Milan, and his active aggression toward other Italian states caused factionalism in France, affecting in particular relations with the Avignon Pope Clement VII, whose Papal dispensation allowed the marriage between Visconti's daughter Valentina to her first cousin Louis, the duke of Orléans, the King's brother. See Adams, 8

- ^ Ratified on 26 September 1396. See Adams (2010), 8

- ^ The day before the wedding, Isabeau signed a treaty clearly spelling out that John the Fearless was cousin to the King (son of his uncle Philip the Bold), and thus of a lower rank than Louis of Orléans, the King's brother. See Adams, 17–18

- ^ In the same year the piece was pawned to pay for Louis of Bavaria's wedding to Anne of Bourbon. See Buettner (2001), 607

Citations

[edit]- ^ Gibbons (1996), 68

- ^ a b c Tuchman (1978), 416

- ^ a b c Gibbons (1996), 52–53

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 419

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 3–4

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 225–227

- ^ a b c d e f Gibbons (1996), 57–59

- ^ Adams (2010), 223

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 420

- ^ a b c d Tuchman (1978), 455–457

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 547

- ^ Huizinga (2009 edition), 236

- ^ Henneman (1991), 173–175

- ^ a b c Tuchman (1978), 496

- ^ Knecht (2007), 42–47

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 502–504

- ^ a b c Veenstra (1997), 45

- ^ Qtd. in Seward (1987), 144

- ^ a b Hedeman (1991), 137

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gibbons (1996), 54

- ^ Qtd. in Gibbons (1996), 61

- ^ Gibbons (1996), 61

- ^ a b Tuchman (1978), 515

- ^ Famiglietti (1992), 89

- ^ a b c d Gibbons (1996), 62

- ^ Adams (2010), 228

- ^ a b c Adams (2010), 8–9

- ^ Adams (2010), 6–8

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 16–17

- ^ Hedeman (1991), 172

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 13–15

- ^ a b c Adams (2010), 17–18

- ^ a b c Gibbons (1996), 65–66

- ^ Solterer (2007), 214

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 168–174

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 46

- ^ Adams (2010), 175

- ^ a b c d Adams (2010), 19

- ^ Knecht (2007), 52

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 582

- ^ Huizinga (2009 edition), 214

- ^ a b c d e Adams (2010), 21–23

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 36

- ^ Huizinga (2009 edition), 208–209

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 25–26

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 37

- ^ Solterer (2007), 203

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 38

- ^ a b c Adams (2010), 27–30

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 30–32

- ^ Adams (2010), 33–34

- ^ Adams (2010), 35

- ^ a b c d Adams (2010), 36

- ^ a b c Gibbons (1996), 70–71

- ^ a b c Gibbons (1996), 68–69

- ^ a b Tuchman (1978), 586–587

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 516

- ^ Seward (1978), 214

- ^ Adams (2010), 40–44

- ^ Adams (2010), 47

- ^ Famiglietti (1992), 194

- ^ Gibbons (1996), 56

- ^ Gibbons (1996), 55

- ^ Adams (2010), xviii, xiii–xv

- ^ a b Adams (2010), 7

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 45, 81–82

- ^ a b Adams (2010), xiii–xiv

- ^ Qtd. in Veenstra (1997), 46

- ^ Adams (2010), xvi

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 504

- ^ Adams (2010), 58–59

- ^ Qtd. in Adams (2010), 60

- ^ Qtd. in Adams (2010), 61

- ^ Adams (2010), 61

- ^ Buettner (2001), 609

- ^ a b Chapuis, Julien. New York Metropolitan Museum of Art "Patronage at the Early Valois Courts (1328–1461)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 10 November 2012

- ^ Young, Bonne. (1968). "A Jewel of St. Catherine". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Volume 26, 316–324

- ^ Husband (2008), 21–22

- ^ Allen (2006), 590

- ^ Green (2006), 256–258

- ^ a b c d e f Adams (2010), 230–233

- ^ Qtd. in Adams (2010), 251–252

- ^ a b Riezler, Sigmund Ritter von (1893), "Stephan III.", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 36, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 68–71

- ^ a b Tuchman (1978), 145

- ^ a b c d Schwertl, Gerhard (2013), "Stephan II.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 25, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 256–257; (full text online)

- ^ a b Simeoni, Luigi (1937). "Viscónti, Bernabò". Enciclopedia Italiana.

- ^ a b Rondinini, Gigliola Soldi (1989). "DELLA SCALA, Beatrice". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 37.

Sources

[edit]- Adams, Tracy. (2010). The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9625-5

- Allen, Prudence. (2006). The Concept of Woman: The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250–1500, Part 2. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3347-1

- Buettner, Brigitte. (2001). "Past Presents: New Year's Gifts at the Valois Courts, ca. 1400". The Art Bulletin, Volume 83, pp. 598–625

- Bellaguet, Louis-François, ed. Chronique du religieux de Saint-Denys. Tome I 1839; Tome II 1840; Tome III, 1841

- Cochon, Pierre. Chronique Rouennaise, ed. Charles de Robillard de Beaurepaire, Rouen 1870

- Famiglietti, R.C. (1992). Tales of the Marriage Bed from Medieval France (1300–1500). Providence, RI: Picardy Press. ISBN 978-0-9633494-2-2

- Gibbons, Rachel. (1996). "Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France (1385–1422). The Creation of a Historical Villainess". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Volume 6, 51–73

- Green, Karen. (2006). "Isabeau de Bavière and the Political Philosophy of Christine de Pizan". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, Volume 32, 247–272

- Hedeman, Anne D. (1991). The Royal Image: Illustrations of the Grandes Chroniques de France, 1274–1422. Berkeley, CA: UC Press E-Books Collection.

- Henneman, John Bell. (1996). Olivier de Clisson and Political Society in France under Charles V and Charles VI. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3353-7

- Husband, Timothy. (2008). The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean Berry. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13671-5

- Huizinga, Johan. (1924, 2009 edition). The Waning of the Middle Ages. Oxford: Benediction. ISBN 978-1-84902-895-0

- Knecht, Robert. (2007). The Valois: Kings of France 1328–1589. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-522-2

- Seward, Desmond. (1978). The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337–1453. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-17377-0

- Solterer, Helen. (2007). "Making Names, Breaking Lives: Women and Injurious Language at the Court of Isabeau of Bavaria and Charles VI". In Cultural Performances in Medieval France. ed. Eglat Doss-Quimby, et al. Cambridge: DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-112-8

- Tuchman, Barbara. (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-345-34957-6

- Veenstra, Jan R. and Laurens Pignon. (1997). Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France. New York: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10925-4

External links

[edit]- Statue of Isabeau at the Palace of Poitiers, c. 1390

- Little Golden Horse Shrine

- Harley 4380 miniatures, British Library Archived 2020-08-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Queens consort of France

- House of Wittelsbach

- House of Valois

- People of the Hundred Years' War

- 14th-century women regents

- 14th-century regents

- Nobility from Munich

- 1370s births

- 1435 deaths

- Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis

- French Roman Catholics

- German Roman Catholics

- French people of German descent

- 15th-century women regents

- 15th-century regents

- 14th-century French women

- 14th-century French nobility

- 15th-century French women

- 15th-century French people

- 15th-century French nobility

- 14th-century German women

- 14th-century German nobility

- French queen mothers

- Daughters of dukes