Matenadaran

| |

The main/old building of the Matenadaran with the statues of Mesrop Mashtots and his disciple Koryun in the foreground | |

| |

| Established | March 3, 1959[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | 53 Mashtots Avenue, Kentron District, Yerevan, Armenia |

| Coordinates | 40°11′31″N 44°31′16″E / 40.19207°N 44.52113°E |

| Type | Art museum, archive, research institute |

| Collection size | ~23,000 manuscripts and scrolls (including fragments)[2] |

| Visitors | 132,600 (2019)[3] |

| Director | Vahan Ter-Ghevondyan |

| Architect | Mark Grigorian, Arthur Meschian |

| Owner | Government of Armenia, Ministry of Education and Science[4] |

| Website | matenadaran |

The Matenadaran (Template:Lang-hy), officially the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts,[a] is a museum, repository of manuscripts, and a research institute in Yerevan, Armenia. It is the world's largest repository of Armenian manuscripts.[5]

It was established in 1959 on the basis of the nationalized collection of the Armenian Church, formerly held at Etchmiadzin. Its collection has gradually expanded since its establishment, mostly from individual donations. One of the most prominent landmarks of Yerevan, it is named after Mesrop Mashtots, the inventor of the Armenian alphabet, whose statue stands in front of the building.

Name

The word մատենադարան, matenadaran is a compound composed of մատեան, matean ("book" or "parchment") and դարան, daran ("repository"). According to Hrachia Acharian both words are of Middle Persian (Pahlavi) origin.[6] Though it is sometimes translated as "scriptorium" in English,[7] a more accurate translation is "repository or library of manuscripts."[8][9][b] In medieval Armenia, the term matenadaran was used in the sense of a library as all books were manuscripts.[16][c]

Some Armenian manuscript repositories around the world are still known as matenadaran, such as the ones at the Mekhitarist monastery in San Lazzaro, Venice[17] and the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople,[18] and the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Manuscript Depository at the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin.[19] To distinguish it from others, it is often referred to as the Matenadaran of Yerevan,[23] the Yerevan Matenadaran[24][25] or Mashtots Matenadaran.[26][27]

History

Historic predecessors

The earliest mention of a manuscript repository in Armenia was recorded in the writings of the fifth century historian Ghazar Parpetsi, who noted the existence of such a repository at the Etchmiadzin catholicosate in Vagharshapat, where Greek and Armenian language texts were kept. Sources remain silent on the fate of the Etchmiadzin matenadaran until the 15th century, when the catholicosate returned from Sis in Cilicia.[1] Manuscript repositories existed at major monasteries in medieval Armenia, such as at Haghpat (Haghpat matenadaran), Sanahin, Saghmosavank, Tatev, Geghard, Kecharis, Hromkla, and Bardzraberd.[13] In some cases, monastic complexes have separate structures as manuscript repositories. Sometimes manuscripts would be transferred to caves to avoid destruction by foreign invaders.[13] Thousands of manuscripts in Armenia were destroyed over the course of the tenth to fifteenth centuries during the Turkic and Mongol invasions. According to the medieval Armenian historian Stepanos Orbelian, the Seljuk Turks were responsible for the burning of over 10,000 Armenian manuscripts in Baghaberd in 1170.[1]

Modern Matenadaran

As a result of Armenia being a constant battleground between two major powers, the Matenadaran in Etchmiadzin was pillaged several times, the last of which took place in 1804, during the Russo-Persian War. Eastern Armenia's annexation by the Russian Empire in the early 19th century provided a more stable climate for the preservation of the remaining manuscripts.[1] Whereas in 1828 the curators of the Matenadaran catalogued a collection of only 1,809 manuscripts, in 1863 the collection had increased to 2,340 manuscripts, and in 1892 to 3,338 manuscripts.[29] Prior to World War I, in 1914, the collected had reached 4,660 manuscripts.[1][29] The collection was sent to Moscow for safekeeping since Etchmiadzin was close to the war zone.[29]

Thousands of Armenian manuscripts were destroyed during the genocide in the Ottoman Empire.[1]

On December 17, 1920, just two weeks after the demise of the First Republic of Armenia and Sovietization of Armenia, the new Bolshevik government of Armenia issued a decree nationalizing all cultural and educational institutions in Armenia.[29] The issue, signed by Minister of Education Ashot Hovhannisyan, declared the manuscript repository of Etchmiadzin the "property of the working peoples of Armenia."[30] It was put under the supervision of Levon Lisitsian, an art historian and the newly appointed commissar of all cultural and educational institutions of Etchmiadzin.[30][31] In March 1922 the manuscripts from Etchmiadzin that had been sent to Moscow during World War I were ordered to be returned to Armenia by Alexander Miasnikian.[1] 1,730 manuscripts were added to the original 4,660 manuscripts held at Etchmiadzin once they returned to Armenia.[29]

In 1939 the entire collection of manuscripts of Etchmiadzin were transferred to the State Public Library in Yerevan (what later became the National Library of Armenia) by the decision of the Soviet Armenian government.[30][2] In the same year there were 9,382 cataloged manuscripts at the Matenadaran.[32] On March 3, 1959, the Council of Ministers of Soviet Armenian officially established the Matenadaran as an "institute of scientific research with special departments of scientific preservation, study, translation and publication of manuscripts" in a new building.[29] It was named after Mesrop Mashtots, the creator of the Armenian alphabet, in 1962.[2]

Architecture

"The Matenadaran [...] was designed as a modern temple to Armenian civilization."

Old building

The Matenadaran is located at the foot of a small hill on the northern edge of Mashtots Avenue, the widest road in central Yerevan. The building has been variously described as monumental,[34] imposing,[33] and stern.[35] Herbert Lottman called it "solemn and solid-looking."[36] Soviet travel writer Nikolai Mikhailov noted that "In its dimensions and architecture it is a palace."[37] The building is listed as a national monument by the government of Armenia.[38]

It was built in gray basalt[29][39] from 1945 to 1958, however, construction was put on hold from 1947 to 1953 due to unavailability of skilled laborers.[40] Designed by Yerevan's chief architect Mark Grigorian, it is influenced by medieval Armenian architecture.[29] According to Murad Hasratyan, the façade of the Matenadaran is influenced by the 11th century Holy Apostles (Arakelots) church of Ani, the grand capital of Bagratid Armenia.[41][42] However, Grigorian noted that the facade design (an entrance in the middle with two decorative niches on the two sides) has ancient roots, appearing at the ancient Egyptian Temple of Edfu, and then at the Holy Apostles church and the Baronial Palace of Ani.[43] Grigorian designed the entrance hall in line with the gavit (narthex) of Sanahin Monastery.[44] The building was renovated in 2012.[45]

A 1960 mural by Van Khachatur (Vanik Khachatrian) depicting the Battle of Avarayr is located in the entrance hall.[46] Three murals created by Khachatur in 1959 that depict three periods of Armenian history: Urartu, Hellenism, and the Middle Ages—surround the steps leading to the main exhibition hall.[47][46] A large ivory medallion with a diameter of 2 meters depicting the portrait of Vladimir Lenin by Sergey Merkurov was previously hung in the lecture hall.[44] The building has a total floor area of 28,000 square metres (300,000 sq ft).[43] In the 1970s American archivist Patricia Kennedy Grimsted noted that Matenadaran is one of the few places in Soviet Armenia with air conditioning.[48]

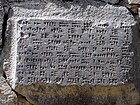

From 1963 to 1967, the statues of historical Armenian scholars, Toros Roslin, Grigor Tatevatsi, Anania Shirakatsi, Movses Khorenatsi, Mkhitar Gosh and Frik, were erected on the left and right wings of the building's exterior. They each represent one field: manuscript illumination, philosophy, cosmology, history, jurisprudence, and poetry, respectively.[49] The statues of Mesrop Mashtots and his disciple Koryun (1962) are located below the terrace where the main building stands.[46] Since the 1970s an open-air exhibition is located near the entrance of the building. On display there are khachkars from the 13th-17th centuries, a tombstone from the Noratus cemetery, a vishap dated 2nd-1st millennia BC, a door from Teishebaini (Karmir Blur), a Urartian archaeological site.[46]

New building

The new building of the Matenadaran was designed by Arthur Meschian, an architect better known as a musician, to house the increasing number of manuscripts.[50] A five-story building, it is three times larger than the old one.[51] It is equipped with a high-tech laboratory, where manuscripts are preserved, restored and digitized.[50] Meschian noted that he designed the new building in a way to not compete with the old one, but instead be a continuation of it.[51] It was initially planned to be constructed in the late 1980s, but was not realized because of the 1988 Armenian earthquake, the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and the economic crisis that ensued.[51] Financed by Moscow-based Armenian businessman Sergei Hambartsumian (US$10 million) and Maxim Hakobian, director of the Zangezur Copper and Molybdenum Combine (US$4 million), it was built from May 2009 to September 2011.[52][50] It was inaugurated on September 20, 2011 on the eve of celebrations of the 20th anniversary of Armenia's independence in attendance of President Serzh Sargsyan, Catholicoi Karekin II of Etchmiadzin and Aram I of Cilicia, Artsakh President Bako Sahakyan, and others.[53][54]

Collection

Currently, the Matenadaran contains a total of some 23,000 manuscripts and scrolls—including fragments.[2] It is, by far, the single largest collection of Armenian manuscripts in the world.[55][56] Furthermore, over 500,000 documents such as imperial and decrees of catholicoi, various documents related to Armenian studies, and archival periodicals.[30][32] The manuscripts cover a wide array of subjects: religious and theological works (Gospels, Bibles, lectionaries, psalters, hymnals, homilies, and liturgical books), texts on history, mathematics, geography, astronomy, cosmology, philosophy, jurisprudence, medicine, alchemy, astrology, music, grammar, rhetoric, philology, pedagogy, collections of poetry, literary texts, and translations from Greek and Syriac.[29][2] The writings of classical and medieval historians Movses Khorenatsi, Yeghishe and Koryun are preserved here, as are the legal, philosophical and theological writings of other notable Armenian figures. The preserved writings of Grigor Narekatsi and Nerses Shnorhali at the Matenadaran form the cornerstone of medieval Armenian literature.

The manuscripts previously held at Etchmiadzin constitute the core of the Matenadaran collection. The rest came from the Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages in Moscow, the Nersisian Seminary and the Armenian Ethnographic Society, both in Tbilisi, and the Yerevan Museum of Literature.[29]

When it was established as a distinct institution in 1959, the Matenadaran had around 10,000 Armenian manuscripts and 4,000 fragments (partial volumes or isolated pages) dating as early as the 5th century.[29][57] At the time there were some one thousand manuscripts in other languages, such as Persian, Syriac, Arabic, Greek, Georgian, Russian, Hebrew, Hindi, Tamil, Latin, Ethiopian (Amharic), and other languages.[29] Some originals, written in other languages, have been saved only in their Armenian translations.[2]

There has been steady growth in the number of manuscripts preserved at the Matenadaran, mostly from gifts from private individuals from the Armenian diaspora.[29] In 1972 there were already 12,960 Armenian manuscripts and nearly two thousand manuscripts in other languages.[58] Among the major donors of the Matenadaran include Harutiun Hazarian from New York (397 manuscripts), Varouzhan Salatian from Damascus (150 manuscripts), Rafael Markossian from Paris (37 manuscripts). Rouben Galichian from London has donated old maps. In 1969 Tachat Markossian, 95, from the village of Gharghan, near Isfahan, in central Iran, donated a 1069 manuscript to the Matenadaran. Written at Narekavank monastery, it is a copy of a Gospel written by Mashtots.[2]

Notable manuscripts

Among the most significant manuscripts of the Matenadaran are the Lazarian Gospel (9th century), the Echmiadzin Gospel (10th century) and the Mughni Gospel (11th century).[58] The first, so called because it was brought from the Lazarian Institute, is from 887 and is one of the Matenadaran's oldest complete volumes. The Echmiadzin Gospel, dated 989, has a 6th-century, probably Byzantine, carved ivory cover.[29][58] The Cilician illuminated manuscripts by Toros Roslin (13th century) and Sargis Pitsak (14th century), two prominent masters, are also held with high esteem.[29]

Three manuscripts are allowed to leave the Matenadaran on a regular basis. The first is the Vehamor Gospel, donated to the Matenadaran by Catholicos Vazgen I in 1975. It probably dates to the 7th century and is, thus, the oldest complete extant Armenian manuscript. The name refers to the mother of the Catholicos (vehamayr), to whose memory Vazgen I dedicated the manuscript. Since Levon Ter-Petrosyan in 1991, all president of Armenia have given their oath on this book.[59][60] The other two, the Shurishkani Gospel (1498, Vaspurakan)[61] and the Shukhonts' Gospel (1669)[62] are taken to the churches of Mughni and Oshakan every year to be venerated.[60]

Other items

Besides manuscripts, the Matenadaran holds a copy of the Urbatagirk, the first published Armenian book (1512, Venice) and all issues of the first Armenian magazine Azdarar ("Herald"), published in Madras, India from 1794 to 1796.[29] The first map printed in Armenian—in Amsterdam in 1695—is also kept at the Matenadaran.[63]

Artsakh branch at Gandzasar

A branch of the Matenadaran was established next to the monastery of Gandzasar in the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) in 2015.[64][65][66]

Publications

Catalogs

The first complete catalog of the Matenadaran manuscripts («Ցուցակ ձեռագրաց») was published in two volumes in 1965 and 1970 with a supplementary volume in 2007. These three volumes listed 11,100 manuscripts kept at the Matenadaran with short descriptions. Since 1984, a more detailed catalog has been published, titled The Main List of Armenian Manuscripts («Մայր ցուցակ հայերէն ձեռագրաց»). As of 2019, ten volumes have been published.[67]

Banber Matenadarani

The Matenadaran publishes the scholarly journal Banber Matenadarani (Բանբեր Մատենադարանի, "Herald of the Matenadaran") since 1941.[68] The articles are usually devoted to the manuscripts and editions of texts contained in the collection. The journal has been praised for its high quality of scholarship.[29]

Significance and recognition

The Matenadaran collection was inscribed by the UNESCO into the Memory of the World Register in 1997, recognizing it as a valuable collection of international significance.[70] American diplomat John Brady Kiesling described the Matenadaran as a "world-class museum."[39]

Anthropologist Levon Abrahamian argues that the Matenadaran has become a sanctuary and temple for Armenians, where manuscripts are treated not only with scientific respect, but also adoration.[71] Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan stated in 2011: "Today, the Matenadaran is a national treasure which has become the greatest citadel of the Armenian identity."[52] Asoghik Karapetyan, director of Museums and Archives of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, called the Matenadaran one of the holiest sites of Armenian identity, along with Mount Ararat and Etchmiadzin.[72]

Thomas de Waal notes that alongside several other institutions (e.g. the Opera, National Gallery) the Matenadaran was central in the Soviet efforts to make Yerevan a "repository of Armenian myths and hopes."[73] Abrahamian argues that the secular Matenadaran continued the traditions of the monastery museums within an atheist state.[74] According to Nora Dudwick, in the Soviet period, the Matenadaran "symbolized the central values of Armenian culture [and signified] to Armenians the high level of culture and learning their ancestors achieved as early as the fifth century."[75]

Karen Demirchyan, the Soviet Armenian leader, wrote in a 1984 book that "For the first time there was no need to save Armenian books and manuscripts from destruction by endless wanderings, for they are preserved in the temple of priceless creations of the people's mind and talent, the Yerevan Matenadaran."[25] The Communist Party's official newspaper, Pravda, wrote in 1989 that no educated Soviet citizen can "imagine spiritual life without the capital's Tretyakov Gallery, the Leningrad Hermitage, and the Yerevan Matenadaran."[76] In 1990 the Soviet Union issued a 5 ruble commemorative coin depicting the Matenadaran.

Visitors

The Matenadaran has become one of the landmarks and major touristic attractions of Yerevan since its establishment.[33] In 2016 it received some 89,000 visitors,[77] and around 132,600 in 2019.[3]

Many foreign dignitaries have visited the Matenadaran, including Leonid Brezhnev (1970),[78][79] Indira Gandhi (1976),[79] Charles, Prince of Wales (2013),[80] Vladimir Putin (2001),[81] Sirindhorn (2018),[82] Boris Tadić (2009),[83] Sergio Mattarella,[84] José Manuel Barroso (2012),[85] Bronisław Komorowski,[86] Heinz Fischer,[87] Valdis Zatlers,[88] Rumen Radev,[89] and others.

Notable staff

Directors

- Gevorg Abov (1940–1952)[90]

- Levon Khachikian (1954–1982)[91]

- Sen Arevshatyan (1982–2007)[92]

- Hrachya Tamrazyan (2007–2016)[93]

- Vahan Ter-Ghevondyan (2018–)[94]

Notable researchers

- Gevorg Emin, poet. He worked briefly at the Matenadaran in the 1940s.[95]

- Rafael Ishkhanyan, linguist, political activist and MP. He worked at the Matenadaran from 1961 to 1963.[96]

- Nouneh Sarkissian, First Lady of Armenia (2018–2022). She worked at the Matenadaran in the 1980s.[97]

- Levon Ter-Petrosyan, the first president of Armenia (1991–98). He worked at the Matenadaran from 1978 to 1991. He was initially a junior researcher, but became a senior researcher in 1985.[98][99][100]

- Asatur Mnatsakanian, philologist and historian. He worked at the Matenadaran from 1940 until his death in 1983.[101]

References

- Notes

- ^ Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի անվան հին ձեռագրերի ինստիտուտ, Mesrop Mashtotsi anvan hin dzeragreri institut

- ^ The Matenadaran has sometimes been called a library.[10][11][12]

- ^ In modern Eastern Armenian, the term gradaran has replaced it for "library", while in Western Armenian the word matenadaran continues to be used for "library".[13]

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Chookaszian, Babken L. [in Armenian]; Zoryan, Levon [in Armenian] (1981). "Մատենադարան (Matenadaran)". Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia Volume 7 (in Armenian). pp. 284-286.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Matenadaran. Historical review". matenadaran.am. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018.

- ^ a b Nazaretyan, Hovhannes (10 February 2022). "Զբոսաշրջությունը հաղթահարում է կորոնավիրուսային շոկը [Tourism overcoming coronavirus shock]". civilnet.am. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022.

- ^ "Հայաստանի Հանրապետության Կառավարության առընթեր Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի անվան հին ձեռագրերի գիտահետազոտական ինստիտուտի (Մատենադարան) վերակազմավորման մասին". arlis.am (in Armenian). Armenian Legal Information System. 6 March 2002.

Հայաստանի Հանրապետության կրթության և գիտության նախարարության ենթակայության «Մատենադարան» Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի անվան հին ձեռագրերի գիտահետազոտական ինստիտուտ»

- ^ Abgarian, G.(1960) "Unfamiliar Libraries VI: The Matenadaran at Erevan." The Book Collector 9 no.2 (summer):146-150.

- ^ Adjarian, Hrachia (1971). Հայերեն արմատական բառարան [Dictionary of Armenian Root Words] (in Armenian) (2nd ed.). Yerevan: Yerevan University Publishing. Volume I, p. 633, Volume III, p. 269

- ^ Kapoutikian, Silva (1981). "The Madenataran: The Parchment Gate of Armenian". The Armenian Review. 34 (2). Hairenik Association: 219.

Manuscripts from the rich collections of the Mechitarist libraries of Venice and Vienna and the Matenadaran (Scriptorium of Ancient Manuscripts) in Erevan, Armenian S.S.R....

- ^ Abrahamian 2006, p. 310.

- ^ Sanjian, Avedis K. (1972). "Colophons of Armenian Manuscripts, 1301-1480: A Source for Middle Eastern History". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 3 (3): 365–371. JSTOR 162806.

...the Matenadaran (Scriptorium) in Erevan, Armenia .... the accurate rendering of 'Matenadaran' is not 'Scriptorium' but 'Library of Manuscripts'.

- ^ Stone, Michael E. (1991). Selected Studies in Pseudepigrapha and Apocrypha: With Special Reference to the Armenian Tradition. BRILL. p. 106. ISBN 9789004093430.

Two MSS in the Matenadaran, Library of Ancient Manuscripts in Erevan...

- ^ Hunt, Lucy-Anne (2009). "Eastern Christian Iconographic and Architectural Traditions: Oriental Orthodox". In Perry, Kenz (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 398. ISBN 9780470766392.

Today, as a result of the wide Armenian diaspora, manuscripts are held in collections all over the world, including Erevan (the Matenadaran Library)...

- ^ Marshall, D. N. (1983). History of Libraries: Ancient and Mediaeval. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd. p. 71.

The evidence of the richness of their output and the speculative thought it is based on is now available to us in the Matenadaran library in Erevan.

- ^ a b c d Abgarian, G. [in Armenian]; Ishkhanian, R. (1981). "Մատենադարան [Matenadaran]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 7 (in Armenian). Yerevan. p. 284.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Aghayan, Eduard [in Armenian] (1976). Արդի հայերենի բացատրական բառարան [Explanatory Dictionary of Modern Armenian] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. p. 974.

- ^ Նոր բառգիրք հայկազեան լեզուի [New Dictionary of the Armenian Language] (in Armenian). Venice: San Lazzaro degli Armeni. 1837. p. 215.

- ^ [13][14][15]

- ^ H., Hakopian (1968). "Հայկական մանրանկարչութիւն. Մխիթարեան մատենադարան ձեռագրաց, Ա, Վենետիկ, 1966". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 3 (3): 264–269.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "APIA 00248". vhmml.org. Hill Museum & Manuscript Library. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020.

Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, Azgayin Matenadaran

- ^ "Opening of new Matenadaran in Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin". Armenpress. 18 October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020.

- ^ Coulie 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Aivazian, Gia (1981). "Problems in Armenian collection development and technical processing in U.S. libraries". Occasional Papers in Middle Eastern Librarianship (1). Middle East Librarians Association: 23.

For example, the Matenadaran of Yerevan has published a two-volume catalog of its manuscripts...

- ^ Samuelian, Thomas J. (1982). Classical Armenian culture: influences and creativity. Scholars Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780891305651.

...together with the original, are preserved in the Matenadaran of Erevan.

- ^ [20][21][22]

- ^ Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2002). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the sixth to the eighteenth century. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780814330234.

- ^ a b Demirchian, K. S. (1984). Soviet Armenia. Moscow: Progress Publishers. p. 9.

- ^ Alexanian, Joseph M. (1995). "The Armenian Version of the New Testament". In Ehrman, Bart D.; Holmes, Michael W. (eds.). The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 9780802848246.

....in the Mashtots Matenadaran in Erevan...

- ^ Stone, Nira; Stone, Michael E. (2007). The Armenians: Art, Culture and Religion. Chester Beatty Library. p. 44. ISBN 9781904832379.

The most important collections of manuscripts today are in the Mashtots' Matenadaran, Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan, Armenia...

- ^ "Old Seminary Building". armenianchurch.org. Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018.

The vast collection of manuscripts of the Armenian Church were housed in the building until the Soviet Period.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Hewsen, Robert H. (1981). "Matenadaran". In Wieczynski, Joseph L (ed.). The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History Volume 21. Academic International Press. pp. 136–138. ISBN 978-0-87569-064-3.

- ^ a b c d Mkhitaryan, Lusine (28 June 2018). "Երբեք չհնացող արժեքներ". Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 6 September 2018.

- ^ Sukiasyan, H. (2014). "Եկեղեցու սեփականության բռնագրավումը Խորհրդային Հայաստանում (1920 թ. դեկտեմբեր – 1921 թ. փետրվար) [Expropriation of church properties in Soviet Armenia (December 1920-February 1921)]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). № 1 (1): 96–97.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "ՀՀ նախագահ Ս.Սարգսյանը ծանոթացավ Մատենադարանի նոր մասնաշենքի շինարարական աշխատանքներին" (in Armenian). Armenpress. 19 September 2008. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- ^ Baliozian, Ara (1979). Armenia Observed. New York: Ararat Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780933706101.

At the end of Lenin Prospekt, where once there rose a bare rock, there now stands the monumental building of Matenadaran — a depository of rare manuscripts and miniatures.

- Egorov, B. (2 January 1967). "A Storage of Ancient Wisdom". The Daily Review. 12. Sovinformburo: 15.

This is the Matenadaran, one of the most monumental structures in Armenia's capital.

- Insight Guides (1991). USSR: the new Soviet Union. APA Productions. p. 312. ISBN 9780134708997.

First of all there is the city's monumental building, the Matenadaran, the world famous library...

- Egorov, B. (2 January 1967). "A Storage of Ancient Wisdom". The Daily Review. 12. Sovinformburo: 15.

- ^ Brook, Stephen (1993). Claws of the Crab: Georgia and Armenia in crisis. London: Trafalgar Square Publishing. p. 172. ISBN 978-1856191616.

Lower down the hill, but still on a prominent slope, stands the Matenadaran, a stern building of grey stone, completed in 1957 in the monumental round-arched style.

- ^ Lottman, Herbert R. (29 February 1976). "Despite Ages of Captivity, The Armenians Persevere". The New York Times. p. 287.

- ^ Mikhailov, Nikolai [in Russian] (1988). A Book About Russia - In the Union Of Equals - Descriptions, Impressions, The Memorable. Moscow: Progress Publishers. p. 111. ISBN 978-5010017941.

- ^ "Ինստիտուտի շենք. Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի անվան հին ձեռագրերի գիտահետազոտական ինստիտուտը (Մատենադարան)". armmonuments.am (in Armenian). Armenian Ministry of Culture.

- ^ a b Kiesling, Brady (2000). Rediscovering Armenia: An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia (PDF). Yerevan/Washington DC: Embassy of the United States of America to Armenia. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-03.

- ^ Grigorian 1960, p. 12.

- ^ Hasratyan, Murad (2011). "Անիի ճարտարապետությունը [Architecture of Ani]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 3 (3): 11.

Գլխավոր՝ արևելյան ճակատի կենտրոնում սլաքաձև կամարով, շթաքարային մշակումով շքամուտքն է` երկու կողմերում զույգ խորշերով (այս հորինվածքը XX դ. նախօրինակ ծառայեց Երևանի Մատենադարանի գլխավոր ճակատի ճարտարապետության համար):

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Hasratyan, Murad. "Անիի Ս. Առաքելոց եկեղեցի [Holy Apostles church of Ani]". armin.am (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020.

Արլ. ճակատի կենտրոնում շքամուտքի խորշն է, երկու կողմերում՝ զույգ խորշերով (այս հորինվածքը նախօրինակ է ծառայել Երևանի Մատենադարանի գլխավոր ճակատի ճարտարապետության համար):

- ^ a b Grigorian 1960, p. 19.

- ^ a b Grigorian 1960, p. 15.

- ^ Danielian, Gayane (20 September 2012). "Մատենադարանի վերանորոգված հին մասնաշենքը բացեց դռները". azatutyun.am. RFE/RL. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Government of the Republic of Armenia (2 November 2004). "Հայաստանի Հանրապետության Երևան քաղաքի պատմության և մշակույթի անշարժ հուշարձանների պետակական ցուցակ [List of historical and cultural monuments of Yerevan]". arlis.am (in Armenian). Armenian Legal Information System. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016.

- ^ Grigorian 1960, p. 18.

- ^ Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy (1973). "Regional Archival Development in the USSR: Soviet Standards and National Documentary Legacies". The American Archivist. 36 (1): 50. doi:10.17723/aarc.36.1.73x7728271272n88.

- ^ "Մատենադարան. Ձեռագրերի գաղտնիքները /Խորհրդավոր մատենադարան/" (in Armenian). Armenian Public TV. 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. at 13:00

- ^ a b c Stepanian, Ruzanna (20 September 2011). "Armenia Expands Famous Manuscript Repository". azatutyun.am. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Danielian, Gayane (19 September 2011). "Մատենադարանի նոր գիտական համալիրը' հայագիտության զարգացման խթան". azatutyun.am (in Armenian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 2 April 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2 April 2019 suggested (help) - ^ a b "President Serzh Sargsyan attended the groundbreaking ceremony for the new extension building of the Mesrop Mashtots Matenadaran". president.am. 14 May 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Landmark museum building opens in Armenia". The Independent. Agence France-Presse. 20 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019.

- ^ "President Serzh Sargsyan attended the ceremony of inauguration of the research compound of Matenadaran". president.am. 20 September 2011. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019.

- ^ Coulie 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Stone, Michael E. (1969). "The Manuscript Library of the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem". Israel Exploration Journal. 19 (1): 20–43. JSTOR 27925161.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (1968). "Science in Seventh-Century Armenia: Ananias of Sirak". Isis. 59 (1). History of Science Society: 40. doi:10.1086/350333. JSTOR 227850. S2CID 145014073.

- ^ a b c Arevshatyan, S. S. "Матенадаран [Matenadaran]". Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). online

- ^ ""Վեհամոր Ավետարանը"". 168.am (in Armenian). 23 March 2018. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022.

- ^ a b Siekierski, Konrad (2014). ""One Nation, One Faith, One Church": The Armenian Apostolic Church and the Ethno-Religion in Post Soviet Armenia". In Agadjanian, Alexander (ed.). Armenian Christianity Today: Identity Politics and Popular Practice. London: Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 9781317178576.

- ^ "Փրկված գրքեր. Շուրիշկանի Ավետարան". mediamax.am (in Armenian). 12 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Շուխոնց հրաշագործ Ավետարանը կտարվի Օշական" (in Armenian). Armenpress. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Museum Complex of the Matenadaran". matenadaran.am. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018.

- ^ "President attended the official ceremony of inauguration of the Depository of Manuscripts in Gandzasar". president.am. The Office to the President of the Republic of Armenia. 21 November 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Մեկնարկել են Մատենադարանի արցախյան մասնաճյուղի շինարարական աշխատանքները". artsakhpress.am (in Armenian). 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Գանձասարի մատենադարանի բացումը". panorama.am (in Armenian). 21 November 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Մայր ցուցակ հայերէն ձեռագրաց մաշտոցեան մատենադարանի". matenadaran.am (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Banber Matenadarani (Herald of the Matenadaran)". matenadaran.am.

- ^ "Banknotes out of Circulation - 1000 dram". cba.am. Central Bank of Armenia. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022.

Monument to Mesrop Mashtotz-creator of the Armenian alphabet, and the Building of Matenadaran

- ^ "Mashtots Matenadaran ancient manuscripts collection". unesco.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020.

- ^ Abrahamian 2006, pp. 87, 310.

- ^ Karapetyan, Asoghik (August 4, 2022). "Մաշտոցյան Մատենադարանը մեր հայկազյան ինքնության և ինքնագիտակցության սրբություն սրբոցն է՝ ինչպես Արարատն ու Սուրբ Էջմիածինը". Facebook (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 8 August 2022.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

- ^ Abrahamian 2006, p. 314.

- ^ Dudwick, Nora C. (1994). Memory, Identity and Politics in Armenia. UMI. p. 310.

- ^ "Impressions of 26 Jun Supreme Soviet Session". Daily Report: Soviet Union (122–125). Foreign Broadcast Information Service: 45. 1989.

- ^ "90.000 visitors in 2016: Geography of tourists visited Armenia's Matenadaran expands". Armenpress. 9 February 2017. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Soviet Union: Domestic Affairs". Daily Report (231). Foreign Broadcast Information Service: B13. 30 November 1970.

- ^ a b "From Indira Gandhi to Belgian royals, Yerevan's treasure Matenadaran boasts A-List visitors". Armenpress. 5 February 2019. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Prince Charles Visiting Armenia". RFE/RL. 29 May 2013. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020.

- ^ "President Vladimir Putin visited the Matenadaran depository of mediaeval Armenian manuscripts". kremlin.ru. 15 September 2001. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Princess of Thailand visits Matenadaran". a1plus.am. A1plus. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022.

- ^ "President of the Republic of Serbia Boris Tadic visits the museum of ancient manuscripts Matenadaran". Photolure. 29 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Italian President visits Matenadaran with daughter". Armenpress. 30 July 2018. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Բարոզոն այցելեց Մատենադարան". panorama.am (in Armenian). 1 December 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 16 December 2018 suggested (help) - ^ "Լեհաստանի նախագահ Բրոնիսլավ Կոմորովսկին այցելել է Մատենադարան". matenadaran.am (in Armenian). 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Ավստրիայի նախագահ Հայնց Ֆիշերն այցելեց Մատենադարան" (in Armenian). PanARMENIAN.Net. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Լատվիայի նախագահ Վ.Զատլերսը տիկնոջ հետ այցելեց Մատենադարան" (in Armenian). Armenpress. 11 December 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 27 November 2022 suggested (help) - ^ "Bulgarian President Rumen Radev visits Matenadaran". Armenpress. 13 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 27 November 2022 suggested (help) - ^ "Աբով Գևորգ [Abov Gevorg]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). 1974. p. 31.

- ^ Editorial (1982). "Մահ Երևանի Ս. Մեսրոպ Մաշտոցի անվան ձեռագրաց Մատենադարանի դիրեկտոր,պրոֆեսոր, ակադեմիկոս Լևոն Ստեփանի Խաչիկյանի". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 39 (3).

- ^ "Sen Arevshatyan dies at 86". A1plus. 25 July 2014.

- ^ "Matenadaran Director Hrachya Tamrazyan passed away". Armenpress. 3 September 2016.

- ^ "Vahan Ter-Ghevondyan elected new director of Matenadaran". panorama.am. 6 March 2018.

- ^ Bardakjian, Kevork B., ed. (2000). A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, 1500-1920: With an Introductory History. Wayne State University Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780814327470.

- ^ "Ռաֆայել Ավետիսի Իշխանյան [Rafayeli Avetisi Ishkhanyan]". ysu.am (in Armenian). Yerevan State University.

- ^ "Mrs. Nouneh Sarkissian". president.am. Office to the President of the Republic of Armenia.

- ^ Colton, Timothy J.; Tucker, Robert C. (1995). Patterns in post-Soviet leadership. Westview Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780813324913.

...the newly elected president of Armenia, Levon Ter Petrosian, formerly a philologist who worked in the Matenadaran...

- ^ Zurcher, Christoph (2009). The Post-Soviet Wars: Rebellion, Ethnic Conflict, and Nationhood in the Caucasus. NYU Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780814797242.

In 1985, he began work at the Yerevan Matenadaran Institute of Ancient Manuscripts as a senior researcher.

- ^ "The first President of Armenia". president.am. Office to the President of Armenia. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020.

- ^ Mikaelian, Vardges (1983). "Ասատուր Մնացականյան [Asatur Mnatsakanian]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). № 7 (7): 100–101.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

Bibliography

- Grigorian, M. V. (1960). "Մատենադարանի շենքի կառուցման մասին [On construction of the Matenadaran building]" (PDF). Banber Matenadarani (in Armenian). 5: 9–20. Archived from the original on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Coulie, Bernard (2014). "Collections and Catalogues of Armenian Manuscripts". In Calzolari, Valentina (ed.). Armenian Philology in the Modern Era: From Manuscript to Digital Text. Brill Publishers. pp. 23–64. ISBN 978-90-04-25994-2.

- Abrahamian, Levon (2006). Armenian Identity In A Changing World. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591858.

Further reading

- Hirsch, David (2010). "Matenadaran". In Suarez, Michael F.; Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199570140.

- Grigorian, Mark (1945). "Մատենադարանի նախագիծը [The Design of the Matenadaran]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). 2 (1–2): 50–52.

- Ayvazyan, Hovhannes, ed. (2012). "Մատենադարան [Matenadaran]". Հայաստան Հանրագիտարան [Armenia Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). National Academy of Sciences of Armenia. pp. 736-739.