Pessimism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

Pessimism is a mental attitude in which an undesirable outcome is anticipated from a given situation. Pessimists tend to focus on the negatives of life in general. A common question asked to test for pessimism is "Is the glass half empty or half full?"; in this situation, a pessimist is said to see the glass as half empty, or in extreme cases completely empty, while an optimist is said to see the glass as half full. Throughout history, the pessimistic disposition has had effects on all major areas of thinking.[1]

Etymology

[edit]The term pessimism derives from the Latin word pessimus, meaning 'the worst'. It was first used by Jesuit critics of Voltaire's 1759 novel Candide, ou l'Optimisme. Voltaire was satirizing the philosophy of Leibniz who maintained that this was the 'best (optimum) of all possible worlds'. In their attacks on Voltaire, the Jesuits of the Revue de Trévoux accused him of pessimisme.[2]: 9

As a psychological disposition

[edit]In the ancient world, psychological pessimism was associated with melancholy, and was believed to be caused by an excess of black bile in the body. The study of pessimism has parallels with the study of depression. Psychologists trace pessimistic attitudes to emotional pain or even biology. Aaron Beck argues that depression is due to unrealistic negative views about the world. Beck starts treatment by engaging in conversation with clients about their unhelpful thoughts. Pessimists, however, are often able to provide arguments that suggest that their understanding of reality is justified; as in Depressive realism or (pessimistic realism).[1] Deflection is a common method used by those who are depressed. They let people assume they are revealing everything which proves to be an effective way of hiding.[3] The pessimism item on the Beck Depression Inventory has been judged useful in predicting suicides.[4] The Beck Hopelessness Scale has also been described as a measurement of pessimism.[5]

Wender and Klein point out that pessimism can be useful in some circumstances: "If one is subject to a series of defeats, it pays to adopt a conservative game plan of sitting back and waiting and letting others take the risks. Such waiting would be fostered by a pessimistic outlook. Similarly if one is raking in the chips of life, it pays to adopt an expansive risk-taking approach, and thus maximize access to scarce resources."[6]

The leading causes of pessimism are genetics, past experience, and social and environmental factors. One study of 5,187 teenage twins and their siblings suggests that genetics may account for one-third of the variance in whether someone leans toward pessimism vs. optimism, with the remaining variance due to their environment, and twin studies suggest that, when it comes to personality, about half the differences between us are because of genetic factors. But Spector points out that throughout our lives, in response to environmental factors, our genes are constantly being dialled up and down as with a dimmer switch, a process known as epigenetics.[7][8]

Criticism

[edit]Pragmatic criticism

[edit]Through history, some have concluded that a pessimistic attitude, although justified, must be avoided to endure. Optimistic attitudes are favored and of emotional consideration.[9] Al-Ghazali and William James rejected their pessimism after suffering psychological, or even psychosomatic illness. Criticisms of this sort however assume that pessimism leads inevitably to a mood of darkness and utter depression. Many philosophers would disagree, claiming that the term "pessimism" is being abused. The link between pessimism and nihilism is present, but the former does not necessarily lead to the latter, as philosophers such as Albert Camus believed. Happiness is not inextricably linked to optimism, nor is pessimism inextricably linked to unhappiness. One could easily imagine an unhappy optimist, and a happy pessimist. Accusations of pessimism may be used to silence legitimate criticism.

The economist Nouriel Roubini (who introduces himself as Dr. Doom) was largely dismissed as a pessimist, for his dire but to some extent accurate predictions of a coming global financial crisis, in 2006. However, financial journalist Justin Fox observed in the Harvard Business Review in 2010 that "In fact, Roubini didn't exactly predict the crisis that began in mid-2007... Roubini spent several years predicting a very different sort of crisis—one in which foreign central banks diversifying their holdings out of Treasuries sparked a run on the dollar—only to turn in late 2006 to warning of a U.S. housing bust and a global 'hard landing'. He still didn't give a perfectly clear or (in retrospect) accurate vision of how exactly this would play out... I'm more than a little weirded out by the status of prophet that he has been accorded since."[10][11][12] Others noted that "The problem is that even though he was spectacularly right on this one, he went on to predict time and time again, as the markets and the economy recovered in the years following the collapse, that there would be a follow-up crisis and that more extreme crashes were inevitable. His calls, after his initial pronouncement, were consistently wrong. Indeed, if you had listened to him, and many investors did, you would have missed the longest bull market run in US market history."[13][14][15][16] Another observed: "For a prophet, he's wrong an awful lot of the time."[17] Tony Robbins wrote: "Roubini warned of a recession in 2004 (wrongly), 2005 (wrongly), 2006 (wrongly), and 2007 (wrongly)" ... and he "predicted (wrongly) that there'd be a 'significant' stock market correction in 2013."[18] Speaking about Roubini, economist Anirvan Banerji told The New York Times: "Even a stopped clock is right twice a day."[19] Economist Nariman Behravesh said: "Nouriel Roubini has been singing the doom-and-gloom story for 10 years. Eventually something was going to be right."[20]

Personality Plus opines that pessimistic temperaments (e.g., melancholy and phlegmatic) can be useful inasmuch as pessimists' focus on the negative helps them spot problems that people with more optimistic temperaments (e.g., choleric and sanguine) miss.[citation needed]

Other forms of pessimism

[edit]Philosophical pessimism

[edit]Philosophical pessimism is not a state of mind or a psychological disposition, but rather it is a worldview or philosophical position that assigns a negative value to life or existence. Philosophical pessimists commonly argue that the world contains an empirical prevalence of pains over pleasures, that existence is ontologically or metaphysically adverse to living beings, and that life is fundamentally meaningless or without purpose.[21]

Epistemological

[edit]There are several theories of epistemology which could arguably be said to be pessimistic in the sense that they consider it difficult or even impossible to obtain knowledge about the world. These ideas are generally related to nihilism, philosophical skepticism, and relativism.[citation needed]

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743–1819) analyzed rationalism, and in particular Immanuel Kant's "critical" philosophy to carry out a reductio ad absurdum[citation needed] according to which all rationalism reduces to nihilism, and thus it should be avoided and replaced with a return to some type of faith and revelation.[citation needed]

Richard Rorty, Michel Foucault, and Ludwig Wittgenstein questioned whether our particular concepts could relate to the world in any absolute way and whether we can justify our ways of describing the world as compared with other ways. In general, these philosophers argue that truth was not about getting it right or representing reality, but was part of subjective social relations of power, or language-games that served our purposes in a particular time. Therefore, these forms of anti-foundationalism, while not being pessimistic per se, reject any definitions that claim to have discovered absolute 'truths' or foundational facts about the world as valid.[22]

Political and cultural

[edit]Philosophical pessimism stands opposed to the optimism or even utopianism of Hegelian philosophies. Emil Cioran claimed "Hegel is chiefly responsible for modern optimism. How could he have failed to see that consciousness changes only its forms and modalities, but never progresses?"[23] Philosophical pessimism is differentiated from other political philosophies by having no ideal governmental structure or political project, rather pessimism generally tends to be an anti-systematic philosophy of individual action.[2]: 7 This is because philosophical pessimists tend to be skeptical that any politics of social progress can actually improve the human condition. As Cioran states, "every step forward is followed by a step back: this is the unfruitful oscillation of history".[24] Cioran also attacks political optimism because it creates an "idolatry of tomorrow" which can be used to authorize anything in its name. This does not mean however, that the pessimist cannot be politically involved, as Camus argued in The Rebel (1951). Pessimism about the human condition was also expressed by Hobbes (1588–1679).[25][26]

There is another strain of thought generally associated with a pessimistic worldview, this is the pessimism of cultural criticism and social decline. Anthony Trollope summarised the attitude with gentle mockery in 1880: "Everything is going wrong. [...] Farmers are generally on the verge of ruin. Trade is always bad. The Church is in danger. The House of Lords isn't worth a dozen years' purchase. The throne totters."[27]

Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West (1918–1922) popularised pessimism. Spengler promoted a cyclic model of history similar to the theories of Giambattista Vico (1668–1744). Spengler believed that modern western civilization was in a "winter" age of decline (German: Untergang). Spenglerian theory was immensely influential in interwar Europe, especially in Weimar Germany. Similarly, traditionalist Julius Evola (1898–1974) thought that the world was in the Kali Yuga, a Dark Age of moral decline.

Intellectuals such as Oliver James correlate economic progress with economic inequality, the stimulation of artificial needs, and affluenza. Anti-consumerists identify rising trends of conspicuous consumption and self-interested, image-conscious behavior in culture. Post-modernists like Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007) have even argued that culture (and therefore our lives) now has no basis in reality whatsoever.[1]

Conservative thinkers, especially social conservatives, often perceive politics in a generally pessimistic way. William F. Buckley famously remarked that he was "standing athwart history yelling 'stop!'", and Whittaker Chambers (1901-1961) was convinced that capitalism was bound to fall to communism, though he himself became staunchly anti-communist. Social conservatives often see the West as a decadent and nihilistic civilization which has abandoned its roots in Christianity and/or Greek philosophy, leaving it doomed to fall into moral and political decay. Robert Bork's Slouching Toward Gomorrah and Allan Bloom's The Closing of the American Mind are famous expressions of this point of view.

Many economic conservatives and libertarians believe that the expansion of the state and the role of government in society is inevitable, and that they are at best fighting a holding action against it.[citation needed][28] They hold that the natural tendency of people is to be ruled and that freedom is an exceptional state of affairs which is now being abandoned in favor of social and economic security provided by the welfare state.[citation needed] Political pessimism has sometimes found expression in dystopian novels such as George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.[29] Political pessimism about one's country often correlates with a desire to emigrate.[30]

During the financial crisis of 2007–08 in the United States, the neologism "pessimism porn" came to describe the alleged eschatological and survivalist thrill some people derive from predicting, reading, and fantasizing about the collapse of civil society through the destruction of the world's economic system.[31][32][33][34]

Puolanka, a municipality located in the Kainuu region in the northern Finland, has been called the "most pessimistic municipality in Finland",[35] and in 2019, the municipality gained worldwide publicity when the BBC published a video about Puolanka, describing it as the "most pessimistic town in the world".[36] Pessimism has a long tradition in the Kainuu region, mostly because Kainuu was a poor region that had often suffered from famines in the late 19th century and early 20th century, which is why the region is also called a "hunger land".[37]

Technological and environmental

[edit]Technological pessimism is the belief that advances in science and technology do not lead to an improvement in the human condition. Technological pessimism can be said to have originated during the Industrial Revolution with the Luddite movement. Luddites blamed the rise of industrial mills and advanced factory machinery for the loss of their jobs and set out to destroy them. The Romantic movement was also pessimistic towards the rise of technology and longed for simpler and more natural times. Poets like William Wordsworth and William Blake believed that industrialization was polluting the purity of nature.[38]

Some social critics and environmentalists believe that globalization, overpopulation and the economic practices of modern capitalist states over-stress the planet's ecological equilibrium. They warn that unless something is done to slow this, climate change will worsen eventually leading to some form of social and ecological collapse.[39] James Lovelock believes that the ecology of the Earth has already been irretrievably damaged, and even an unrealistic shift in politics would not be enough to save it. According to Lovelock, the Earth's climate regulation system is being overwhelmed by pollution and the Earth will soon jump from its current state into a dramatically hotter climate.[40] Lovelock blames this state of affairs on what he calls "polyanthroponemia", which is when: "humans overpopulate until they do more harm than good." Lovelock states:

The presence of 7 billion people aiming for first-world comforts…is clearly incompatible with the homeostasis of climate but also with chemistry, biological diversity and the economy of the system.[40]

Some radical environmentalists, anti-globalization activists, and Neo-luddites can be said to hold to this type of pessimism about the effects of modern "progress". A more radical form of environmental pessimism is anarcho-primitivism which faults the agricultural revolution with giving rise to social stratification, coercion, and alienation. Some anarcho-primitivists promote deindustrialization, abandonment of modern technology and rewilding.

An infamous anarcho-primitivist is Theodore Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber, who engaged in a nationwide mail bombing campaign. In his 1995 Unabomber manifesto, he called attention to the erosion of human freedom by the rise of the modern "industrial-technological system".[41] The manifesto begins thus:

The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in "advanced" countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation. It will certainly subject human beings to greater indignities and inflict greater damage on the natural world, it will probably lead to greater social disruption and psychological suffering, and it may lead to increased physical suffering even in "advanced" countries.

One of the most radical pessimist organizations is the voluntary human extinction movement, which argues for the extinction of the human race through antinatalism.

Pope Francis' controversial 2015 encyclical on ecological issues is rife with pessimistic assessments of the role of technology in the modern world.

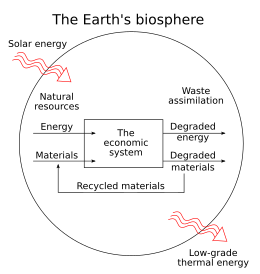

Entropy pessimism

[edit]

"Entropy pessimism" represents a special case of technological and environmental pessimism, based on thermodynamic principles.[42]: 116 According to the first law of thermodynamics, matter and energy is neither created nor destroyed in the economy. According to the second law of thermodynamics—also known as the entropy law—what happens in the economy is that all matter and energy is transformed from states available for human purposes (valuable natural resources) to states unavailable for human purposes (valueless waste and pollution). In effect, all of man's technologies and activities are only speeding up the general march against a future planetary "heat death" of degraded energy, exhausted natural resources and a deteriorated environment—a state of maximum entropy locally on earth; "locally" on earth, that is, when compared to the heat death of the universe, taken as a whole.

The term "entropy pessimism" was coined to describe the work of Romanian American economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, a progenitor in economics and the paradigm founder of ecological economics.[42]: 116 Georgescu-Roegen made extensive use of the entropy concept in his magnum opus on The Entropy Law and the Economic Process.[43] Since the 1990s, leading ecological economist and steady-state theorist Herman Daly—a student of Georgescu-Roegen—has been the economic profession's most influential proponent of entropy pessimism.[44][45]: 545

Among other matters, the entropy pessimism position is concerned with the existential impossibility of allocating Earth's finite stock of mineral resources evenly among an unknown number of present and future generations. This number of generations is likely to remain unknown to us, as there is no way—or only little way—of knowing in advance if or when mankind will ultimately face extinction. In effect, any conceivable intertemporal allocation of the stock will inevitably end up with universal economic decline at some future point.[46]: 369–371 [47]: 253–256 [48]: 165 [49]: 168–171 [50]: 150–153 [51]: 106–109 [45]: 546–549 [52]: 142–145

Entropy pessimism is a widespread view in ecological economics and in the degrowth movement.

Legal

[edit]Bibas writes that some criminal defense attorneys prefer to err on the side of pessimism: "Optimistic forecasts risk being proven disastrously wrong at trial, an embarrassing result that makes clients angry. On the other hand, if clients plead based on their lawyers' overly pessimistic advice, the cases do not go to trial and the clients are none the wiser."[53]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Bennett, Oliver (2001). Cultural Pessimism: Narratives of Decline in the Postmodern World. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0936-9.

- ^ a b Dienstag, Joshua Foa (2009). Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6911-4112-1.

- ^ Kirszner, Laurie (January 2012). Patterns for College Writing. United States: Bedford/St.Martins. p. 477. ISBN 978-0-312-67684-1.

- ^ Beck, AT; Steer, RA; Kovacs, M (1985), "Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation", American Journal of Psychiatry, 142 (5): 559–563, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.6328, doi:10.1176/ajp.142.5.559, PMID 3985195

- ^ Beck, AT; Weissman, A; Lester, D; Trexler, L (1974), "The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale", Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42 (6), Journal of Consulting and Clinical: 861–5, doi:10.1037/h0037562, PMID 4436473

- ^ Wender, PH; Klein, DF (1982), Mind, Mood and Medicine, New American Library

- ^ Mavioğlu, Rezan Nehir; Boomsma, Dorret I.; Bartels, Meike (2015-11-01). "Causes of individual differences in adolescent optimism: a study in Dutch twins and their siblings". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 24 (11): 1381–1388. doi:10.1007/s00787-015-0680-x. ISSN 1435-165X. PMC 4628618. PMID 25638288.

- ^ "Can science explain why I'm a pessimist?". BBC News. 2013-07-10. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

- ^ Michau, Michael R. ""Doing, Suffering, and Creating": William James and Depression" (PDF). web.ics.purdue.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ^ Justin Fox (May 26, 2010). "What Exactly is Nouriel Roubini Good For?", Harvard Business Review.

- ^ David H. Freedman (2010). Wrong: Why experts* keep failing us--and how to know when not to trust them, Little, Brown.

- ^ Thomas I. Palley (2013). From Financial Crisis to Stagnation; The Destruction of Shared Prosperity and the Role of Economics.

- ^ David Lawrence (February 4, 2022). "Why year-ahead stock predictions are usually wrong," North Bay Business Journal.

- ^ Jayson MacLean (May 6, 2020). "Nouriel Roubini warns of Great Depression just like he did last year (and the year before that)," Cantech Letter.

- ^ "Market gurus:Overrated Dr Roubini flops—again," Moneylife, March 10, 2011.

- ^ "How much should you trust economists' predictions?", AZ Central, May 8, 2014.

- ^ Joe Keohane (January 9, 2011). "That guy who called the big one? Don’t listen to him." The Boston Globe.

- ^ Tony Robbins, Peter Mallouk (2017). Unshakeable; Your Financial Freedom Playbook

- ^ Emma Brockes (January 23, 2009). "He told us so," The Guardian.

- ^ Helaine Olen (March 30, 2009). "The Prime of Mr. Nouriel Roubini", Entrepreneur.

- ^ For discussions around the views and arguments of philosophical pessimism see:

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (2010) [1818]. Welchman, Alistair; Janaway, Christopher; Norman, Judith (eds.). The World as Will and Representation. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511780943. ISBN 978-0-521-87184-6.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (2018) [1844]. Welchman, Alistair; Janaway, Christopher; Norman, Judith (eds.). The World as Will and Representation. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9780511843112. ISBN 978-0-521-87034-4.

- Benatar, David (2017). The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life's Biggest Questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063381-3.

- Ligotti, Thomas (2011). The Conspiracy Against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror. New York: Hippocampus Press. ISBN 978-0-9844802-7-2. OCLC 805656473.

- Saltus, Edgar (2012) [1885]. The Philosophy of Disenchantment. Project Gutenberg.

- Coates, Ken (2014). Anti-Natalism: Rejectionist Philosophy from Buddhism to Benatar. First Edition Design Pub. ISBN 978-1-62287-570-2.

- Lugt, Mara van der (2021). Dark Matters: Pessimism and the Problem of Suffering. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20662-2.

- Sully, James (1877). Pessimism: A History and a Criticism. London: Henry S. King & Co.

- ^ "Richard Rorty on Truth and Language - New Learning Online". newlearningonline.com. Retrieved 2024-08-14.

- ^ Cioran, Emil. A short history of decay, pg 146

- ^ Cioran, Emil. A short history of decay, pg 178

- ^ Walton, C.; Johnson, P.J. (2012). Hobbes's 'Science of Natural Justice'. International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées. Springer Netherlands. p. 64. ISBN 978-94-009-3485-6. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ Rothman, A. (2017). The Pursuit of Harmony: Kepler on Cosmos, Confession, and Community. University of Chicago Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-226-49697-9. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ^ Trollope, Anthony (1 January 2003) [1880]. "62: The Brake Country". The Duke's Children. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^

Compare:

Holmes, Jack E.; Engelhardt, Michael J.; Elder, Robert E. (1991). American Government: Essentials & Perspectives. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 16. ISBN 9780070297678. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

[Those] more sympathetic to libertarian views on the role of government have been in the position of fighting a holding action against the growth of government [...].

- ^ Lowenthal, D (1969), "Orwell's Political Pessimism in '1984'", Polity, 2 (2): 160–175, doi:10.2307/3234097, JSTOR 3234097, S2CID 156005171

- ^ Brym, RJ (1992), "The emigration potential of Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Russia: recent survey results", International Sociology, 7 (4): 387–95, doi:10.1177/026858092007004001, PMID 12179890, S2CID 5989051

- ^ Pessimism Porn: A soft spot for hard times, Hugo Lindgren, New York, February 9, 2009; accessed July 8, 2012

- ^ Pessimism Porn? Economic Forecasts Get Lurid, Dan Harris, ABC News, April 9, 2009; accessed July 8, 2012

- ^ Apocalypse and Post-Politics: The Romance of the End, Mary Manjikian, Lexington Books, March 15, 2012, ISBN 0739166220

- ^ Pessimism Porn: Titillatingly bleak media reports, Ben Schott, New York Times, February 23, 2009; accessed July 8, 2012

- ^ "Pessimistinen Puolanka". Yle (in Finnish). 3 January 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "The world's most pessimistic town". BBC. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Väisänen, Heino (1998). Kainuun kansan waiheita vv. 1500 – 1900, p. 213. Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. ISBN 952-91-0373-5

- ^ "Romanticism". Wsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ The New York Review of Books Gray, John. "The Global Delusion, John Gray".

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b The New York Review of Books Flannery, Tim. "A Great Jump to Disaster?, Tim Flannery".

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ The Washington Post: Unabomber Special Report: INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY AND ITS FUTURE

- ^ a b Ayres, Robert U. (2007). "On the practical limits to substitution" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 61: 115–128. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.011. S2CID 154728333.

- ^ Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1971). The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Full book accessible at Scribd). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674257801.

- ^ Daly, Herman E. (2015). "Economics for a Full World". Scientific American. 293 (3): 100–7. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0905-100. PMID 16121860. S2CID 13441670. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b Kerschner, Christian (2010). "Economic de-growth vs. steady-state economy" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 18 (6): 544–551. Bibcode:2010JCPro..18..544K. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.10.019.

- ^ Daly, Herman E., ed. (1980). Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Essays Towards a Steady-State Economy (PDF contains only the introductory chapter of the book) (2nd ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0716711780.

- ^ Rifkin, Jeremy (1980). Entropy: A New World View (PDF). New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670297177. Archived from the original (PDF contains only the title and contents pages of the book) on 2016-10-18.

- ^ Boulding, Kenneth E. (1981). Evolutionary Economics. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0803916487.

- ^ Martínez-Alier, Juan (1987). Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631171461.

- ^ Gowdy, John M.; Mesner, Susan (1998). "The Evolution of Georgescu-Roegen's Bioeconomics" (PDF). Review of Social Economy. 56 (2): 136–156. doi:10.1080/00346769800000016.

- ^ Schmitz, John E.J. (2007). The Second Law of Life: Energy, Technology, and the Future of Earth As We Know It (Author's science blog, based on his textbook). Norwich: William Andrew Publishing. ISBN 978-0815515371.

- ^ Perez-Carmona, Alexander (2013). "Growth: A Discussion of the Margins of Economic and Ecological Thought". In Meuleman, Louis (ed.). Transgovernance. Advancing Sustainability Governance (Article accessible at SlideShare). Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 83–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28009-2_3. ISBN 9783642280085.

- ^ Bibas, Stephanos (Jun 2004), Plea Bargaining outside the Shadow of Trial, vol. 117, Harvard Law Review, pp. 2463–2547.

Further reading

[edit]- Schmitt, Mark, Spectres of Pessimism: A Cultural Logic of the Worst, Palgrave, 2023, ISBN 978-3-031-25351-5

- Slaboch, Matthew W., A Road to Nowhere: The Idea of Progress and Its Critics, The University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018, ISBN 0-812-24980-1

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Contestabile, Bruno (2016). "The Denial of the World from an Impartial View". Contemporary Buddhism. 17: 49–61. doi:10.1080/14639947.2015.1104003. S2CID 148168698.

- Pessimism by Mara Van der Lugt in The Philosopher.