Franco-Mongol alliance: Difference between revisions

Reinstated balanced intro |

OR essay. Material mentionned elsewhere in the article. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The Mongols again invaded Syria several times between 1281 and 1312, sometimes in alliance or attempted alliance<ref name=tyerman-816/> with the Christians, though there were considerable logistical difficulties involved, which usually resulted in the forces arriving months apart, and being unable to satisfactorily combine their activities. Ultimately, the attempts at alliance bore little fruit, and ended with the victory of the Egyptian [[Mamluk]]s, the total eviction of both the Franks and the Mongols from [[Palestine]] by 1303, and a treaty of peace between the Mongols and the Mamluks in 1322. |

The Mongols again invaded Syria several times between 1281 and 1312, sometimes in alliance or attempted alliance<ref name=tyerman-816/> with the Christians, though there were considerable logistical difficulties involved, which usually resulted in the forces arriving months apart, and being unable to satisfactorily combine their activities. Ultimately, the attempts at alliance bore little fruit, and ended with the victory of the Egyptian [[Mamluk]]s, the total eviction of both the Franks and the Mongols from [[Palestine]] by 1303, and a treaty of peace between the Mongols and the Mamluks in 1322. |

||

==Disagreements on the existence of an alliance== |

|||

There is disagreement among historians on whether or not a formal alliance actually existed between the Franks and the Mongols. Most scholars agree that there were many ''attempts'' at an alliance, but that the attempts were ultimately unsuccessful. French historians seem more inclined to say that an alliance existed, while other historians do not. The French historian Grousset, writing in the 1930s, used the terms "L'Alliance Franco-Mongole" and "La coalition Franco-Mongole."<ref>Grousset, p521: "Louis IX et l'Alliance Franco-Mongole", p.653 "Seul Edward I comprit la valeur de l'Alliance Mongole", p.686 "la coalition Franco-Mongole dont les Hospitaliers donnaient l'exemple"</ref> The modern French historian Demurger referred to it as "The strategy of the Mongol alliance in action."<ref>Demurger, p.147 "Cette expedition avait surtout l'avantage de sceller, par un acte concret l'alliance Mongole", Demurger p.145 "La strategie de l'alliance Mongole en action", "De Molay anime la lutte pour la reconquete de Jerusalem, en s'appuyant sur une alliance avec les Mongols" (Demurger, back cover)</ref> However, the 1911 ''[[Encyclopedia Britannica]]'' said, "The alliance with the Mongols remained, from the first to the last, something of a [[chimera]]." In the 1979 edition the ''Britannica'' does not refer to an alliance but does include a section on "Crusaders military relations." Amin Maalouf, in ''The Crusades Through Arab Eyes,'' called the alliance a "dream", and said that in 1260 the Franks of Acre "took a neutral position generally favorable to the Muslims", not the Mongols. Indeed, it was the Crusader treaty with the Mamluks that allowed the Muslims to proceed north unhindered, and defeat the Mongols in the pivotal [[Battle of Ain Jalut]]. Dr. [[Malcolm Barber]], world authority on the Knights Templar, called the alliance a "project" and "the possibility of an alliance." Dr. Sylvia Schein referred to it as "plans for an alliance." Sean Martin referred to it as a "combined force." Angus Stewart called it "Franco-Mongole entente."<ref>Angus Stewart says "Franco-Mongol entente" [http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract;jsessionid=482F302AE5E221049B3D878097CB336E.tomcat1?fromPage=online&aid=289586]</ref> And David Nicolle, another acknowledged expert on the Knights Templar, said that the Mongols were "potential allies", but that overall the major players were the Mamluks and the Mongols, and that the Christans were just "pawns in a greater game." Prawer said simply, "The attempts of the crusaders to create an alliance with the Mongols failed."<ref>Prawer, p. 32. "The attempts of the crusaders to create an alliance with the Mongols failed."</ref> Christopher Tyerman, in ''God's War: A New History of the Crusades'', described it as "an attempt to capture the chimera of a Franco-Mongol anti-Islamic alliance" that turned out to be a "false hope for Outremer as for the rest of Christendom."<ref>Tyerman, pp. 798-799</ref> He also described it as "pursuing the will of the wisps of a Mongol alliance with the il-khan of Persia",<ref>Tyerman, p. 813</ref> and added, "The Mongol alliance, despite six further embassies to the west between 1276 and 1291, led nowhere."<ref name=tyerman-816/> |

|||

==Religious affinity== |

==Religious affinity== |

||

Revision as of 05:04, 17 September 2007

This article is actively undergoing a major edit for a little while. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. This page was last edited at 05:04, 17 September 2007 (UTC) (16 years ago) – this estimate is cached, . Please remove this template if this page hasn't been edited for a significant time. If you are the editor who added this template, please be sure to remove it or replace it with {{Under construction}} between editing sessions. |

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. |

A Franco-Mongol alliance,[1][2][3] or attempts towards such an alliance,[4][5] occurred between the mid-1200s and the early 1300s, starting around the time of the Seventh Crusade. During this period, the Franks (designating the Crusader States, the Frank state of Little Armenia,[6] the military orders of the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitallers, and the countries of Western Europe)[7] laboured to form an alliance with the Mongol Ilkhanate, in order to combat their common Muslim enemy in the Middle East, first the Abbasid Caliphate, followed by the Ayyubid dynasty and then the Egyptian Mamluks.

There were numerous exchanges of letters, gifts, and emissaries between the Mongols and the Europeans, as well as offers for varying types of cooperation. Few of the attempts resulted in anything substantial, though there were a few coordinated military efforts. The most successful points of both collaboration and non-collaboration was in 1260, when most of Muslim Syria was briefly conquered by the joint efforts of the Mongols, the Christian forces of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, the Crusader States of the Principality of Antioch,[8] and the County of Tripoli.[9] However, the Mongol forces had to withdraw shortly thereafter for internal reasons, after which the Franks of Acre entered into a treaty with the Egyptian Mamluks, allowing the Muslims to obtain a major and historic success against the Mongols at 1260's Battle of Ain Jalut.

The Mongols again invaded Syria several times between 1281 and 1312, sometimes in alliance or attempted alliance[10] with the Christians, though there were considerable logistical difficulties involved, which usually resulted in the forces arriving months apart, and being unable to satisfactorily combine their activities. Ultimately, the attempts at alliance bore little fruit, and ended with the victory of the Egyptian Mamluks, the total eviction of both the Franks and the Mongols from Palestine by 1303, and a treaty of peace between the Mongols and the Mamluks in 1322.

Religious affinity

Overall, Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time, though shamanism, Buddhism, and Christianity were the most popular in the early 1200s. When Temujin, the shamanist man who would later become Genghis Khan, declared the Baljuna Covenant with 17 of his companions, several of them were Christian.[11] Many Mongol tribes, such as the Kerait,[12] the Naiman, the Merkit, and to a large extent the Kara Khitan, were Nestorian Christian.[13] All the sons of Genghis Khan had taken Christian wives, from the tribe of the Kerait. While the men were away at battle, the empire was effectively run by the Christian women.[14][15] Genghis Khan's grandson Sartaq was Christian;[16] as was the general Kitbuqa,[17] commander of the Mongol forces of the Levant. Under Mongka, another of Genghis Khan's grandsons, the main religious influence was that of the Nestorians.[18]

Other Mongols, such as Genghis Khan's grandson Berke, the ruler of the Golden Horde quarter of the empire, were highly favourable to Islam, leading to conflicts between Mongol clans, as in the Berke-Hulagu war. However, in the 1200s, as regards the quarter of the Mongol empire known as the Ilkhanate, the greatest affinity appears to have been with the Christians. Genghis's grandson Hulagu, though he was an avowed shamanist, was nevertheless very tolerant of Christianity. His mother, his favorite wife, and several of his closest collaborators were Nestorian Christians. And when he invaded Syria, though he slaughtered other defenders, he bowed to his wife's request and allowed the Christians to live.[19] Marital alliances with Western powers also occurred, as in the 1265 marriage of Maria Despina Palaiologina, the Christian daughter of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, with Hulagu's son, the Mongol khan Abaqa, who himself was a Buddhist.

Early contacts (1209-1244)

Among Europeans, there had long been rumors and expectations that a great Christian ally would come from "the East." These rumors circulated as early as the First Crusade, and usually surged in popularity after the loss of a battle by the Crusaders, which resulted in a natural human desire that a Christian hero would arrive from a distant land, to help save the day. This resulted in the development of a legend about a figure known as Prester John. The legend fed upon itself, and some individuals who came from the East were greeted with the expectations that they might be the long-awaited Christian heroes.

Around 1210, news of the battles of Kuchlug, leader of the largely Christian tribe of the Naiman, against the powerful Khwarezmian Empire of Muhammad, reached the West. It was told that Prester John was again battling the Muslims in the East, now with Kuchlug filling the role of the mythical Christian king.[20]

During the Fifth Crusade, as the Christians were unsuccessfully laying siege to the Egyptian city of Damietta in 1221, these legends again conflated with the reality of the Mongols under Ghengis Khan.[21] Rumors circulated that a "Christian king of the Indies", a King David who was either Prester John or one of his descendants, had been attacking Muslims in the East, and was on his way to help the Christians in their Crusades.[22] In a letter dated June 20, 1221, Pope Honorius III even commented about "forces coming from the Far East to rescue the Holy Land".[23]

The Mongols first invaded Persian territory in 1220, destroying the Kwarizmian kingdom of Jelel-ad-Din, and then conquering the kingdom of Georgia. Genghis Khan then returned to Mongolia, and Persia was reconquered by Muslim forces.[24]

In 1231, a huge Mongol army again came in 1231 under the general Chormaqan. He ruled over Persia and Azerbaijan from 1231 to 1241.[25] In 1242, Baichu further invaded the Seldjuk kingdom, ruled by Kaikhosrau, in modern Turkey, again eliminating an enemy of Christendom.[26]

Papal overtures (1245-1248)

The Mongol invasion of Europe subsided in 1242 with the death of the Great Khan Ögedei, successor of Genghis Khan. However, the relentless march westward of the Mongols had displaced the Khawarizmi Turks, who themselves moved west, and on their way to ally with the Ayyubid muslims in Egypt, took Jerusalem from the Christians in 1244.[27] This event prompted Christian kings to prepare for a new Crusade, decided by Pope Innocent IV at the First Council of Lyons in June 1245, and revived hopes that the Mongols, who had their Nestorian Christian princesses among them and had brought so much destruction to Islam, could be converted to Christianity and become allies of Christendom.[28][29]

In 1245, Pope Innocent IV issued bulls and sent an envoy in the person of the Franciscan John of Plano Carpini to the "Emperor of the Tartars". The message asked the Mongol ruler to become a Christian and stop his aggression against Europe. Carpini was in Karakorum for the installation of the new Khan on April 8, 1246,[30] Khan Güyük, bu Guyuk's reply was simply to demand the submission of the Pope[31] and a visit from the rulers of the West in homage to Mongol power:

"You must say with a sincere heart: "We will be your subjects; we will give you our strength". You must in person come with your kings, all together, without exception, to render us service and pay us homage. Only then will we acknowledge your submission. And if you do not follow the order of God, and go against our orders, we will know you as our enemy."

In 1245 Innocent had sent another mission, through another route, led by the Dominican Ascelin of Lombardia, also bearing letters. The mission met with the Mongol commander Baichu near the Caspian Sea in 1247. Baichu, who had plans to capture Baghdad, welcomed the possibility of an alliance and had envoys, Aïbeg and Serkis, accompany the embassy back by to Rome, where they stayed for about a year.[33] They met with Innocent IV in 1248, who again appealed to the Mongols to stop their killing of Christians, and complained that the alliance was not moving forward.[34][35]

In the meantime, in 1247, faced with the impending attack of the Mongols in his own country, the Christian king Hetoum I of Cilician Armenia chose alliance over surrender or annihilation, and sent his brother Sempad in allegiance to the Mongol court of Guyuk.[36]

Seventh Crusade: Saint Louis and the Mongols (1248-1254)

Louis IX of France, also called Saint Louis, had a series of written exchanges with the Mongol rulers of the period, and went on crusade twice, once in 1248 and once in 1270.

His contacts with the Mongols started in 1248, with the Seventh Crusade. After Louis left France and disembarked in Cyprus, he was met on December 20, 1248, in Nicosia by two Mongol envoys, Nestorians from Mossul named David and Marc, bearing a letter from Eljigidei, the Mongol ruler of Armenia and Persia.[37] They communicated a proposal to form an alliance against the Muslims Ayyubids, whose Caliphate was based in Baghdad.[38] The medieval historian Jean de Joinville said about the communiques:

"Whilst the King was tarrying in Cyprus, the great King of the Tartars sent messengers to him, greeting him courteously, and bearing word, amongst other things, that he was ready to help him conquer the Holy Land and deliver Jerusalem out of the hand of the Saracens. The King received them most graciously, and sent in reply messengers of his own, who remained away two years, before they returned to him. Moreover the King sent to the King of the Tartars by the messengers a tent made in the style of a chapel, which cost a great deal, for it was made wholly of good fine scarlet cloth. And to entice them if possible into our faith, the King caused pictures to be inlaid in the said chapel, portraying the annunciation of Our Lady, and all the other points of the Creed. These things he sent them by two Preaching Friars, who knew Arabic, in order to show and teach them what they ought to believe."

— "The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville", Chap. V, Jean de Joinville.[39]

In response, Louis had sent André de Longjumeau, a Dominican priest, as an emissary to the Great Khan Güyük in Mongolia. However, Güyük died before the emissary arrived at his court, and his widow Oghul Ghaimish simply gave the emissary a gift and a condescending letter to take back to King Louis.[40]

Meanwhile, Eljigidei, the Great Khan's lieutenant in Asia Minor, planned an attack on the Muslims in Baghdad in 1248. This advance was, ideally, to be conducted in alliance with Louis, in concert with the Seventh Crusade.[citation needed] According to the 13th century monk and historian Guillaume de Nangis, Eljigidei suggested that King Louis should land in Egypt, while Eljigidei attacked Baghdad, in order to prevent the Saracens of Egypt and those of Syria from joining forces.[41] Louis IX did go on to attack Egypt, starting with the capture of the port of Damietta. However, Güyük's early death, caused by drink, made Eljigidei postpone operations until after the interregnum, and Louis lost his army at Mansurah.

In 1253, Louis tried again to garner support, this time seeking allies from among both the Ismailian Assassins and the Mongols.[42] When he received word that the Mongol leader Sartaq, son of Batu, had converted to Christianity,[43] Louis dispatched an envoy to the Mongol court in the person of the Franciscan William of Rubruck, who went to visit the Great Khan Möngke in Mongolia. William entered into a famous competition at the Mongol court, as the khan encouraged a formal debate between the Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, to determine which faith was correct.[44] But even after the competition, Möngke replied only with a letter to William in 1254, asking for the King's submission to Mongol authority.[45]

Louis finally had to return to France, due to the death of his mother and regent, Blanche de Castille.

Joint conquest of the Middle East (1258-1260)

A certain amount of military collaboration between the Christians and the Mongols did not really take place until 1258-1260, when the Franks under Bohemond VI Lord of Antioch and Tripoli, the Christian Armenians under his father-in-law Hetoum I, and the Christian Georgians allied with the Mongols under Hulagu. Though some historians refer to this not as an alliance, so much as the Mongols acting in concert with their own conquered vassal states.[46] The Georgians had already been vassals of the Tartars since 1243, and the Armenians since 1247.[47]

Conquest of Baghdad (1258)

On February 15, 1258, the Mongols were successful in the Siege of Baghdad, an event often considered as the single most catastrophic event in the history of Islam. Bohemond VI was present alongside the Mongols during the siege.[48] The Christian Georgians, vassals of the Mongols since 1243 and led by Hasan Brosh the Armeno-Georgian prince of Khatshen,[49][50] had been the first to breach the walls, and were among the fiercest in their destructions.[51] When they conquered the city, the Mongols demolished buildings, burned entire neighborhoods, massacred nearly 80,000 men, women, and children. But at the intervention of the Mongol's Nestorian Christian wife, the Christian inhabitants were spared.[52][53] Hulagu offered the royal palace to the Nestorian Catholicus Mar Makikha, and ordered a cathedral to be built for him.[54]

The conquest of Baghdad marked the tragic end of the Abassid Caliphate. The city of Baghdad, which had been the jewel of Islam and one of the largest and most powerful cities in the world for 500 years, became a minor provincial town. Never again was the Near East to dominate civilization.[55]

Conquest of Syria and the Holy Land (1260)

After Baghdad, the combined Christian and Mongol forces then conquered Muslim Syria, domain of the Ayyubid dynasty, taking together the city of Aleppo. Later, on March 1, 1260, the Mongols, the Armenians and the Franks of Antioch took Damascus[56][57] under the Christian Mongol general Kitbuqa.[58][59] This invasion destroyed the Ayyubid Dynasty, theretofore powerful ruler of large parts of the Levant, Egypt and Arabia, and the last Ayyubid king An-Nasir Yusuf died in 1260.[60] With the Islamic power centers of Baghdad and Damascus gone, the center of Islamic power transferred to the Egyptian Mamluks in Cairo.

Some of the conquered cities (including Lattakieh) were given to Bohemond VI, and numerous presents were given to him by Hulagu,[61] but the Mongols insisted that the Greek Christian patriarch Euthymius be installed in Antioch.[62] All this resulted in a temporary excommunication for Bohemond.[63][64]

Following a new conflict in Turkestan, Hulagu had to stop the Mongol invasion before it reached Egypt, and he had to depart with the bulk of his forces, leaving only about 10,000 Mongol horsemen in Syria under Kitbuqa to occupy the conquered territory,[65] including Nablus and Gaza, but not Jerusalem.[17]

Sidon incident (1260)

With Mongol territory now bordering the Franks, a few incidents occurred, one of them leading to large-scale trouble in Sidon. Julian de Grenier, Lord of Sidon and Beaufort, described by his contemporaries as irresponsible and light-headed, took the opportunity to raid and plunder the area of the Bekaa in Mongol territory. When Kitbuqa sent his nephew with a small force to obtain redress, they were ambushed and killed by Julian. Kitbuqa responded forcefully by raiding the city of Sidon, although the Castle of the city was left unattained.[17][66] Another similar incident occurred when John II of Beirut and some Templars led a raid into Galilee.[67] These events generated a significant level of distrust between the Mongols and the Crusader forces, whose own center of power was now in the coastal city of Acre.

Battle of Ain Jalut (1260)

In 1260, the Franks of Acre maintained a position of cautious neutrality between the Mongols and the Mamluks. The powerful Venetian commercial interests in the city regarded with concern the expansion of the northern trade routes opened by the Mongols and serviced by the Genoese, and they favoured an appeasement policy with the Mamluks, that would support their traditional trade routes to the south. In May 1260 they sent a letter to Charles of Anjou, complaining about Mongol expansion and Bohemond's subservience to them, and asking for his support.[68]

They sent the Dominican David of Ashby to the court of Hulagu in 1260,[69] but also entered into a passive alliance with the Egyptian Mamluks, which allowed the Mamluk forces to move through Christian territory unhampered.[70] This allowed the Mamluks to counter-attack the Mongols, at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3, 1260. It was the first major battle that the Mongols lost, and effectively set the western border for what had seemed an unstoppable Mongol expansion.[71]

Further exchanges

On April 10, 1262, the Mongol leader Hulagu sent through John the Hungarian a new letter to the French king Louis IX from the city of Maragheh, offering again an alliance. The letter mentioned Hulagu's intention to capture Jerusalem for the benefit of the Pope, and asked for Louis to send a fleet against Egypt. Though Hulegu promised the restoration of Jerusalem to the Christians, he also still insisted on Mongol sovereignty, in their quest for conquering the world. King Louis transmitted the letter to Pope Urban IV, who answered by asking for Hulagu's conversion to Christianity.[72] The Pope also issued the papal bull Exultavit cor nostrum, which tentatively agreed to Hulegu's plans, but only cautiously.[22]

The Mamluk leader Baibars then began to threaten Antioch, which (as a vassal of the Armenians) had earlier supported the Mongols.[73][74]

Bohemond VI was again present at the court of Hulagu in 1264, trying to obtain as much support as possible from Mongol rulers against the Mamluk progression. His presence is described by the Armenian saint Vartan:[75]

"In 1264, l'Il-Khan had me called, as well as the vartabeds Sarkis (Serge) and Krikor (Gregory), and Avak, priest of Tiflis. We arrived at the place of this powerful monarch at the beginning of the Tartar year, in July, period of the solemn assembly of the kuriltai. Here were all the Princes, Kings and Sultans submitted by the Tartars, with wonderful presents. Among them, I saw Hetoum I, king of Armenia, David, king of Georgia, the Prince of Antioch (Bohemond VI), and a quantity of Sultans from Persia.

— Vartan, trad. Dulaurier.[76]

In 1265, the new Khan Abaqa further pursued Western cooperation. He corresponded with Pope Clement IV through 1267-1268, and reportedly sent a Mongol ambassador in 1268. Abaqa proposed a joint alliance between his forces, those of the West, and the father of Abaqa's wife, the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaeologos. Abaqa received responses from Rome and from Jaume I of Aragon, though it is unclear if this was what led to Jaume's unsuccessful expedition to Acre in 1269.[22]

The Mamluk leader Baibars finally took the Armenian city of Antioch in 1268, and all of northern Syria was quickly lost, leaving Bohemond with no estates except Tripoli.[77] In 1271, Baibars sent a letter to Bohemond threatening him with total annihilation and taunted him for his former alliance with the Mongols:

"Our yellow flags have repelled your red flags, and the sound of the bells has been replaced by the call: "Allâh Akbar!" (...) Warn your walls and your churches that soon our siege machinery will deal with them, your knights that soon our swords will invite themselves in their homes (...) We will see then what use will be your alliance with Abagha"

— Letter from Baibars to Bohemond VI, 1271[78]

Crusader-Mongol relations during the Eighth and Ninth Crusades

Abagha (1234-1282), was the second Mongol emperor in Persia, controlling that quarter of the Mongol empire known as the Ilhanate. A devout Buddhist, he reigned from 1265-1282. Upon his succession, he received the hand of the Christian Maria Despina Palaiologina, the illegitimate daughter of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, in marriage.[79] During his reign, he attempted to convert the Muslims and harassed them mercilessly by promoting Nestorian and Buddhist interests ahead of the Muslims, many of whom attempted to assassinate him.

In preparation for the Eighth Crusade (the second of Louis IX), letters about an alliance were again exchanged between Pope Gregory X and the Mongols. When Prince Edward of England arrived in Acre in 1271, ambassadors were sent to Abaqa to arrange a joint venture against Egypt. Abaqa did send a force of 10,000 Mongol horsemen, but nothing significant was accomplished.[22] However, a 10-year truce was at least obtained between the Barons of Acre and the Egyptian Mamluks.[80] Also in 1271, one of the vassals of Bohemond, named Barthélémy de Maraclée, lord of Khrab Marqiya, a small coastal town between Baniyas and Tortosa, is recorded as having fled from the Mamluk offensive, taking refuge in Persia at the Mongol Court of Abagha, where he exhorted the Mongols to intervene in the Holy Land.[81][82]

Eighth crusade: offer of alliance from Pope Clement IV (1267)

In the 1260s, the Mamluks were extending their conquests in Syria during the 1260s, putting the Syrian Franks in a difficult situation. In 1267, Pope Clement IV and James I of Aragon sent an ambassador to the Mongol ruler Abaqa in the person of Jayme Alaric de Perpignan.[83] In his 1267 letter written from Viterbo, the Pope said:

"The kings of France and Navarre, taking to heart the situation in the Holy Land, and decorated with the Holy Cross, are readying themselves to attacks the enemies of the Cross. You wrote to us that you wished to join your father-in-law (the Greek emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos) to assist the Latins. We abundantly praise you for this, but we cannot tell you yet, before having asked to the rulers, what road they are planning to follow. We will transmit to them your advice, so as to enlighten their deliberations, and will inform your Magnificence, through a secure message, of what will have been decided."

— 1267 letter from Pope Clement IV to Abagha[84]

Jayme Alaric would return to Europe in 1269 with a Mongol embassy, again proposing an alliance. Pope Clement welcomed Abagha's proposal in a non-committal manner, but did inform him of an upcoming Crusade.

Louis IX, who had been preparing for a new Crusade since March 24, 1267, left on July 1, 1270. However, the Eighth Crusade went to Tunis in modern Tunisia instead of Syria, apparently with the intention of first conquering Tunis, and then to move his troops along the coast to reach Alexandria. Louis IX would die of illness in Tunis, and according to legend, his last words being "Jerusalem".[85]

The Pope's communications were also followed by a small crusade initiated by James I of Aragon, but ultimately handled by his two bastards Fernando Sanchez and Pedro Fernandez after a storm forced most of the fleet to return, which arrived in Acre in December 1269. At that time, Abagha had to face an invasion in Khorasan by fellow Mongols from Turkestan, and could only commit a small force on the Syrian frontier from October 1269, only capable of brandishing the threat of an invasion.[86]

When Abagha finally defeated his eastern enemies near Herat in 1270, he wrote to Louis IX offering military support as soon as the Crusaders landed in Palestine.[86]

Ninth crusade: operational alliance against the Mamluks (1269-1274)

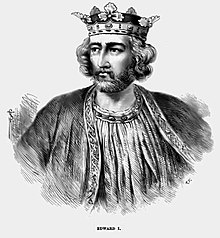

In 1269, the English Prince Edward (the future Edward I), inspired by tales of his uncle, Richard the Lionheart, and the second crusade of the French King Louis, started on a Crusade of his own, the Ninth Crusade.[87] The number of knights and retainers that accompanied Edward on the crusade was quite small,[88] possibly around 230 knights, with a total complement of approximately 1,000 people, transported in a flotilla of 13 ships.[89][90] Many of the members of Edward's expedition were close friends and family including his wife Eleanor of Castile, his brother Edmund, and his first cousin Henry of Almain.

When Edward finally arrived in Acre, on May 9, 1271, he sent an embassy to the Mongol ruler Abagha. According to the French historian Runciman, Edward's plan was to use the help of the Mongols to attack the Muslim leader Baibars.[91] The embassy was led by Reginald Russel, Godefrey Welles and John Parker.[92] [93] The success of Edward's venture is in dispute. According to the medieval historian William of Tyre, Abagha responded positively to Edwaard's request:

"The messengers that Sir Edward and the Christians had sent to the Tartars to ask for help came back to Acre, and they did so well that they brought the Tartars with them, and raided all the land of Antioch, Aleppo, Haman and La Chamele, as far as Caesarea the Great. And they killed all the Sarazins they found."

Accounts of modern historians, however, differ. According to the French historians Runciman and Grousset, Abagha answered positively to Edward's request in a letter dated September 4, 1271. In mid-October 1271, the Mongol troops requested by Edward arrived in Syria and ravaged the land from Aleppo southward. Abagha, occupied by other conflicts in Turkestan could only send 10,000 Mongol horsemen under general Samagar from the occupation army in Seljuk Anatolia, plus auxiliary Seljukid troops,[96] but they triggered an exodus of Muslim populations (who remembered the previous campaigns of Kithuqa) as far south as Cairo.[92] The Mongols defeated the Turcoman troops that protected Aleppo, putting to flight the Mamluk garrison in that city, and continued their advance to Maarat an-Numan and Apamea.[96] However, other historians make no mention of coordinated actions between Edward and the Mongols. According to Geoffrey Hindley, Edward's forces merely engaged in some fairly ineffectual raids that did not actually achieve success in gaining any new territory.[97] According to Tyerman, Edward "saw some action" in defending Acre from Baibars in December 1271, and "launched a couple of military promenades into the surrounding countryside."[98] Even Runciman agrees that when Edward engaged in a raid into the Plain of Sharon, he proved unable to even take the small Mamluk fortress of Qaqun.[99] Baibars later taunted Edward for not even being able to take a small fortified house.[100]

As a result of the military operations, Edward still obtained the signature of a 10-year truce between the city of Acre and the Mamluks, signed in 1272.[99] In June 1272, Edward was wounded by an assassination attempt with a poisoned dagger, but he survived, and after recuperating returned to England in September,[97] arriving in 1274.

Despite his limited activity in the Holy Land, Edward's reputation was greatly enhanced by his participation in the crusade and he was hailed by some contemporary commentators as a new Richard the Lionheart. Furthermore, some historians believe Edward was inspired by the design of the castles he saw while on crusade, such as the Krak des Chevaliers, and incorporated similar features into the castles he built to secure portions of Wales, such as Caernarfon Castle.

When Baibars mounted a counter-offensive from Egypt on November 12, the Mongols had already retreated beyond the Euphrates, unable to face the full Mamluk army.

New attempt at a joint invasion of Syria (1280-1281)

Following the death of Baibars in 1277, and the ensuing disorganisation of the Muslim realm, the Mongols seized the opportunity and organized a new invasion of Syrian land:

"Abagha ordered the Tartars to occupy Syria, the land and the cities, and remit them to be guarded by the Christians."

— Monk Hayton of Corycus, "Fleur des Histoires d'Orient", circa 1300[101]

Abagha and Leo III of Armenia urged the Franks to start a new Crusade, but only the Hospitallers and Edward I (who could not come for lack of funds) responded favourably.[102] In September 1280, the Mongols attacked northern Syria, and conquered Aleppo on October 20, before retreating. The Hospitallers of Marquab made combined raids into the Buqaia, and won several engagements against the Sultan.[103] The Mongols sent envoys to Acre to request military support for a campaign the following winter, informing the Franks that they would bring 50,000 Mongol horsemen and 50,000 Mongol infantry, but the request apparently remained without a response.[104]

After the expiration of the old truce from 1271, the new Muslim sultan Qalawun signed a new 10-year truce on May 3, 1281 with the Barons of Acre (a truce he would later breach)[105] and a second 10-year truce with Bohemond VII of Tripoli, on July 16, 1281. The truce also authorized pilgrim access to Jerusalem.[106]

The announced Mongol invasion started in September 1281. They were joined by the Armenians under Leo III, and by about 200 Hospitaliers knights of the fortress of Marqab,[107][108] who considered they were not bound by the truce with the Mamluks.[109]

"In the year 1281 of the incarnation of Christ, the Tatars left their realm, crossed Aygues Froides with a very great army and invaded the land of Aleppo, Haman and La Chemele and did great damage to the Sarazins and killed many, and with them were the king of Armenia and some Frank knights of Syria."

— Le Chevalier de Tyre, Chap. 407[110]

On October 30, 1281, 50,000 Mongol troops, together with 30,000 Armenians, Georgians, Greeks, and the Hospitalier Knights of Marqab fought against the Muslim leader Qalawun at the Second Battle of Homs, but they were repelled, with heavy losses on both sides.[109]

Arghun's proposals for a new crusade (1285-1291)

In 1285, the new Mongol ruler Arghun, son of Abaqa, again sent an embassy and a letter to Pope Honorius IV, a Latin translation of which is preserved in the Vatican.[111][112] Arghun's letter mentioned the links that Arghun's family had to Christianity, and proposed a combined military conquest of Muslim lands:[113]

"As the land of the Muslims, that is, Syria and Egypt, is placed between us and you, we will encircle and strangle ("estrengebimus") it. We will send our messengers to ask you to send an army to Egypt, so that us on one side, and you on the other, we can, with good warriors, take it over. Let us know through secure messengers when you would like this to happen. We will chase the Saracens, with the help of the Lord, the Pope, and the Great Khan."

— Extract from the 1285 letter from Arghun to Honorius IV, Vatican[114]

Apparently left without an answer, Arghun sent another embassy to European rulers in 1287, headed by the Nestorian Rabban Bar Sauma, with the objective of contracting a military alliance to fight the Muslims in the Middle East, and take the city of Jerusalem.[111] The responses were positive but vague. Sauma returned in 1288 with positive letters from Pope Nicholas IV, Edward I of England, and Philip IV the Fair of France.[115] According to the medieval Syriac History of the two Nestorian Chinese monks, Bar Sawma of Khan Balik and Markos of Kawshang, as translated in Sir Wallis Budge's book The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China, Philip seemingly responded positively to the request of the embassy, gave him numerous presents, and sent one of his noblemen, Gobert de Helleville, to accompany Bar Sauma back to Mongol lands:

"And the King Philip said: if it be indeed so that the Mongols, though they are not Christians, are going to fight against the Arabs for the capture of Jerusalem, it is meet especially for us that we should fight [with them], and if our Lord willeth, go forth in full strength. . . And he said unto us, "I will send with you one of the great Amirs whom I have here with me to give an answer to King Arghon"; and the king gave Rabban Sawma gifts and apparel of great price."

— "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China[116]

Gobert de Helleville departed on February 2, 1288, with two clerics Robert de Senlis and Guillaume de Bruyères, as well as arbaletier Audin de Bourges. They joined Bar Sauma in Rome, and accompanied him to Persia.[117]

According to a medieval historian, King Edward was also said to have welcomed the embassy enthusiastically:

"King Edward rejoiced greatly, and he was especially glad when Rabban Sauma talked about the matter of Jerusalem. And he said "We the kings of these cities bear upon our bodies the sign of the Cross, and we have no subject of thought except this matter. And my mind is relieved on the subject about which I have been thinking, when I hear that King Arghun thinketh as I think"

— Account of the travels of Rabban Bar Sauma, Chap. VII.[118]

In 1289, Arghun sent a third mission to Europe, in the person of Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoese who had settled in Persia. The objective of the mission was to determine at what date concerted Christian and Mongol efforts could start. Arghun committed to march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disembarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Buscarel was in Rome between July 15 and September 30, 1289, and in Paris in November-December 1289. He remitted a letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, answering to Philippe's own letter and promises, offering the city of Jerusalem as a potential prize, and attempting to fix the date of the offensive from the winter of 1290 to spring of 1291:[119]

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter [1290], worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

Buscarel then went to England to bring Arghun's message to King Edward I. He arrived in London January 5, 1290. Edward, whose answer has been preserved, answered enthusiastically to the project but remained evasive and failed to make a clear commitment.[122]

Arghun then sent a fourth mission to European courts in 1290, led by a certain Andrew Zagan, who was accompanied by Buscarel of Gisolfe and a Christian named Sahadin.[123]

In 1290, the Pope sent the Franciscan John of Montecorvino to the Mongol court in Khanbaliq.[124]

All these attempts to mount a combined offensive failed. On March 1291, Saint-Jean-d'Acre was conquered by the Mamluks in the Siege of Acre. Arghun himself died on March 10th, 1291, putting an end to his efforts towards combined action.[125]

According to the 20th century historian Runciman, "Had the Mongol alliance been achieved and honestly implemented by the West, the existence of Outremer would almost certainly have been prolonged. The Mamluks would have been crippled if not destroyed; and the Ilknate of Persia would have survived as a power friendly to the Christians and the West"[126]

Joint operations in the Levant (1298-1303)

From around 1298, there were increased efforts at military collaboration between the Franks and the Mongols. The current Mongol leader Ghazan had been baptized and raised as a Christian, though he had became a Muslim upon accession to the throne.[127] He retained however a strong enmity towards the Egyptian Mamluks.

The plan was to coordinate actions between the Christian military orders, the King of Cyprus, the aristocracy of Cyprus and Little Armenia and the Mongols of the khanate of Ilkhan (Persia).[128] The Christian forces of Cyprus and Armenia were determined to reconquer the Holy Land, in liaison with the Mongol offensives.[129] According to some French authors, the Knights Templar and their leader Jacques de Molay were the artisans of an alliance with the Mongols against the Mamluks, but other historians dispute this (see above section on Disagreements on the existence of an alliance).[130]

In 1298 or 1299, the military orders and their leaders, including Jacques de Molay, Otton de Grandson and the Great Master of the Hospitallers, briefly campaigned in Armenia, in order to fight off an invasion by the Mamluks.[131][132][133] However, they were not successful, and soon, the fortress of Roche-Guillaume in the Belen pass, the last Templar stronghold in Antioch, was lost to the Muslims.[134]

Campaign of winter 1299-1300

In the summer of 1299, King Hethoum sent a message to the Mongol khan of Persia, Ghâzân to obtain his support. Ghazan marched with his forces towards Syria and sent letters to the Franks of Cyprus (the King of Cyprus, and the heads of the Knights Templar, the Hospitallers and the Teutonic Knights), inviting them to come join him in his attack on the Mamluks in Syria. Ghazan's first letter was sent on October 21, which arrived 15 days later. He sent a second letter in November.[135]

There is no record of any reply, but Ghazan moved ahead, and the Mongols successfully took the city of Aleppo.[134] There, Ghazan was joined by King Hethoum II of Armenia and some of his own forces, including some Armenian Templars and Hospitallers.[134] The Mongols and their Christian allies defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar on December 23 or 24, 1299,[134] and the remaining Mamluk forces retreated back to Egypt. Damascus was the next to surrender, somewhere between December 30, 1299, and January 6, 1300, though its Citadel resisted.[136][137][138] The Mongols then retreated the bulk of their forces in February, possibly because their horses needed fodder.

Also in early 1300, two Frank rulers, Guy d'Ibelin and Jean II de Giblet, had moved in with their troops from Cyprus in response to Ghazan's earlier call, and established a base in the castle of Nefin in Gibelet on the Syrian coast with the intention of joining him, but Ghazan was already gone.[139][140]

In July, the Crusader forces from Cyprus attempted to assist, engaging in coastal raids that stretched from Alexandria in Egypt, up to Tortosa. The ships then returned to Cyprus, and prepared for an attack on Tortosa in late 1300. James II of Aragon also sent a congratulation letter to Ghazan for his victories.[141]

The fate of Jerusalem in 1300

There is still disagreement among modern historians as to whether or not the Mongols may have occupied Jerusalem around this time. After the Mamluk forces retreated south to Egypt, and the Mongol forces retreated north, with promises to return in the winter of 1300-1301 to attack Egypt, [142] there existed a period of about four months from February to May 1300, when the Mongol il-Khan was the "de facto" lord of the Holy Land.[143] According to the medieval historian the Templar of Tyre, there were also 10,000 Mongol troops still in the area, under the command of the Mongol leader Mulai, but even that small force had to retreat when the Mamluks returned in May 1300.[144][145][146]

There are also reports that the Mongols engaged in raids as far south as Jerusalem and Gaza, though not all historians accept them as reliable.[147][148][149][150]

Phillips, in The Medieval Expansion of Europe, states categorically that "Jerusalem had not been taken or even besieged."[151] In The Crusades, Riley-Smith chalked up the stories to rumors.[152] Schein, in her 1979 article "Gesta Dei per Mongolos", stated "The alleged recovery of the Holy Land never happened,"[153] David Morgan in The Mongols, using Schein as a reference, agrees that of the taking of Jerusalem, "this had not in fact happened."[154]

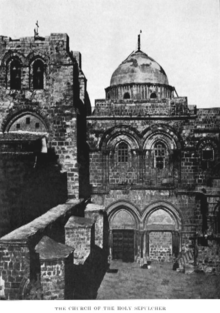

However, in The Crusaders and the Crusader States, Andrew Jotischky used Schein's 1979 article and later 1991 book to state, "after a brief and largely symbolic occupation of Jerusalem, Ghazan withdrew to Persia."[155] Steven Runciman in "A history of the Crusades, III" stated that Ghazan penetrated as far as Jerusalem, but not until the year 1308.[156] Alain Demurger in The Last Templar: The Tragedy of Jacques de Molay simply said, "Did they occupy Jerusalem? There is a tradition that Hethoum celebrated mass in the Saint Sepulchre on the day of Epiphany (January 6th)"[157]

Historical clues

The Arab historian Yahia Michaud, in the 2002 book Ibn Taymiyya, Textes Spirituels I-XVI, describes that there were some firsthand accounts at the time, of forays of the Mongols into Palestine,[158] and quotes two ancient Arab sources stating that Jerusalem was one of the cities that was raided by the Mongols.[159]

In February 1300, a Francisan monk in Nicosia, Cyprus wrote a letter saying that King Hethoum had celebrated mass in Jerusalem,[160] evidently at the Holy Sepulchre on January 6, 1300. The modern French historian Demurger said, "There is a tradition that Hethoum celebrated a religious office at the Saint-Sepulcre on the day of the Epiphany (January 6).[161]

Dr. Schein's research also compiled a detailed list of any fragments of sources which might indicate that Jerusalem had in fact been either conquered by the Mongols, or at least briefly occupied. For example, she listed in both her 1979 paper and 1991 book Fidelis Crucis, the medieval Armenian source which stated that the Armenian King Hethoum II, with a small force, had reached the outskirts of Cairo and then spent some fifteen days in Jerusalem visiting the Holy Places:

"The king of Armenia, back from his raid against the Sultan, went to Jerusalem. He found that all the enemies had been put to flight or exterminated by the Tatars, who had arrived before him. As he entered into Jerusalem, he gathered the Christians, who had been hiding in caverns out of fright. During the 15 days he spent in Jerusalem, he held Christian ceremonies and solemn festivities in the Holy Sepulchre. He was greatly comforted by his visits to the places of the pilgrims. He was still in Jerusalem when he received a certificate from the Khan, bestowing him Jerusalem and the surrounding country. He then returned to join Ghazan in Damas, and spend the winter with him"

— Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Historiens Armeniens I, p.660[162]

Schein expanded on this slightly in her 1991 book, by mentioning in a footnote that the Mongols must have conquered Jerusalem because they had removed a gate from the Dome of the Rock, and transferred it to Damascus.[163] She also pointed out that in a 1301 letter, the Sultan al-Malik an-Nasir accused Ghazan of introducing the Christian Armenians and Georgians into Jerusalem.[164] And in her 1991 book, Schein expanded her earlier statement to say that the Armenian information about Hetoum's visit was confirmed by Arab chroniclers.[165]

"The Tatars then made a raid against Jerusalem and against the city of Khalil. They massacred the inhabitants of these two cities (...) it is impossible to describe the amount of atrocities, destructions, plundering they did, the number of prisonners, children and women, they took as slaves".

— Ibn Abi L-Fada'Il, Histoire.[166]

However, Schein's interpretation of the sources has been strongly challenged by Angus Donal Stewart in his 2001 book The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks, where he called the Armenian statement an "absurd claim" from an unreliable source, and said that the Arab chroniclers did not confirm it in any way.[167] He also had criticisms for several other errors in Schein's work.

Other reports mention that Christians were in Jerusalem in April to celebrate Easter.[168].

In a general comment on Jerusalem in her 2005 posthumous book Gateway to the Heavenly City: Crusader Jerusalem and the Catholic West (1099-1187), Schein said nothing about Mongol conquest, but simply noted: "After 1187 and for the rest of the Middle Ages, Earthly Jerusalem, ruled by the Moslems (except for the short period of 1229-1244), was to loom large in all types of late medieval apocalypticism."[169]

European rumors about the conquest of Jerusalem

Most scholars agree that whatever the facts involving Jerusalem, that the situation led to wild rumors in Europe, though there is disagreement as to when exactly the rumors started, when the word about the Mongol activities reached Europe, and which sources from the time were reliable, and which were embellished, misinformed, or simply false.

According to Demurger in The Last Templar, the first announcement of the Mongol success was in a letter written in Cyprus in March 1300.[170] According to Schein, the earliest letter was dated March 19, 1300, and was probably based on accounts from Venetian merchants who had just arrived from Cyprus, which they had left on February 3, 1300.[171] The account gave a more or less accurate picture of the Mongol successes in Syria, but then expanded to say that the Mongols had "probably" taken the Holy Land by that point.

"Ghazan dispatched messengers to the kings of Jerusalem and Cyprus, and to the communes and to the religious orders, asking them to come to him in Damas or Jerusalem, so that he could remit to them all the lands the Christians held at the time of Godefroy de Bouillon".

— Letter of Thomas Gras, Cyprus, March 24, 1300[172]

One thing that is certain, is that whatever their source, that once they had reached Europe, the rumours spread and were inflated widely, due to wishful thinking, and the urban legend environment of large crowds that had gathered in Rome for the Jubilee. The story grew to say (falsely) that the Mongols had taken Egypt, that the Mongol Ghazan had appointed his brother as the new king there, and that the Mongols were going to further conquer Barbary and Tunis. The rumors also stated that Ghazan had freed the Christians who were held captive in Damascus and in Egypt, and that some of those prisoners had already made their way to Cyprus. From Italy, the rumors spread to Austria and Germany, and then to France.[173]

By April 1300, Pope Boniface was sending a letter announcing the "great and joyful news to be celebrated with special rejoicing,"[152] that the Mongol Ghazan had conquered the Holy Land and offered to hand it over to the Christians. In Rome, as part of the Jubilee celebrations in 1300, the Pope ordered processions to "celebrate the recovery of the Holy Land," and he further encouraged everyone to depart for the newly-recovered area. Edward I was asked to encourage his subjects to depart as well, to visit the Holy Places. And Pope Boniface even referred to the recovery of the Holy Land from the Mongols, in his bull Ausculta fili.

In the summer of the Jubilee year, Pope Boniface VIII received a dozen ambassadors, dispatched from various kings and princes. One of the groups was of 100 Mongols, led by the Florentine Guiscard Bustari, the ambassador for the il-khan. The embassy, abundantly mentioned in contemporary sources, participated in the Jubilee ceremonies. Supposedly this ambassador was also the man nominated by Ghazan to supervise the re-establishment of the Franks, in the territories that Ghazan was going to return to them. There was great rejoicing for a short time, but the Pope soon learned about the true state of affairs in Syria, from which in fact Ghazan had withdrawn the bulk of his forces in February 1300, and the Mamluks had reclaimed by May.[174] But the rumors continued through at least September 1300.[175]

19th century reconstructions

Though most modern historians disagree with this interpretation,[176] the story of the 1299/1300 capture of Jerusalem was retold by (primarily French) historians during the following centuries, and even expanded in the 19th century to claims that Jerusalem was taken not by Mongols, but by Jacques de Molay, Grand Master of the Knights Templar. In 1805, the French historian Raynouard said, "In 1299, the Grand-Master was with his knights at the taking of Jerusalem."[177] The story was also expanded to say that Jacques de Molay had actually been placed in charge of one of the Mongol divisions. In the 1861 edition of the French encyclopedia, the Nouvelle Biographie Universelle, it says in the "Molay" article:

"Jacques de Molay was not inactive in this decision of the Great Khan. This is proven by the fact that Molay was in command of one of the wings of the Mongol army. With the troops under his control, he invaded Syria, participated in the first battle in which the Sultan was vanquished, pursued the routed Malik Nasir as far as the desert of Egypt: then, under the guidance of Kutluk, a Mongol general, he was able to take Jerusalem, among other cities, over the Muslims, and the Mongols entered to celebrate Easter"

— Nouvelle Biographie Universelle, "Molay" article, 1861.[178]

There is even a painting, Molay Prend Jerusalem, 1299 ("Molay takes Jerusalem, 1299"), hanging in the French national museum in Versailles, created in 1846 by Claude Jacquand,[179] which depicts the supposed event in 1299. However, De Molay was certainly nowhere near Jerusalem at the time. His actual whereabouts were that he was recorded in Armenia in 1298-1299 for a failed military operation, and may or may not have participated in the Crusader coastal raids during the summer of 1300 on such cities as Alexandria and Acre. He was also surely on the island of Ruad in November 1300, attempting (unsuccessfully) to retake the coastal city of Tortosa. But there are no reliable sources that say that he was anywhere near the landlocked city of Jerusalem in 1299 or 1300.[180]

Campaign of winter 1300-1301

According to Le Templier de Tyr, Ghazan sent ambassadors to Cyprus in 1300, led by the Italian Isol le Pisan, the Mongols' chief ambassador to Cyprus. In agreement with the Cypriotes, a joint embassy was then sent to the Pope.[181][182]

Frankish seaborne operations

The Mongol leader Ghazan had sent letters in late 1299 requesting Frankish help, primarily with naval operations.[183] No assistance arrived for his attack on Syria in December 1299 (the troops of Guy d'Ibelin and Jean II de Giblet only arrived from Cyprus in early 1300), and Ghazan could only rely on Christian Georgians and Armenians as well as some Templars and Hospitallers from Armenian garrisons,[184] but in July 1300, a fleet of sixteen galleys with some smaller vessels was equipped in Cyprus.[185][183][186] The fleet was commanded by King Henry II of Jerusalem, the king of Cyprus, accompanied by his brother, Amalric, Lord of Tyre; Jacques de Molay of the Templars; Isol le Pisan; and the head of the Hospitallers. According to the medieval historian the Templar of Tyre, the ships flew the banner of Ghazan.[183] The ships left Famagusta on July 20, 1300, to raid the coasts of Egypt and Syria: Rosette,[183] Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa, and Maraclea, before returning to Cyprus.[186]

Ruad bridgehead

When the ships arrived back in Cyprus, another message came from Ghazan asking to coordinate operations, inviting the Cypriots to meet him in Armenia.[186] The Cypriots then prepared a land-based force of approximately 600 men: 300 from Amalric of Lusigan, and similar contingents from the Templars and Hospitallers.[186] The men and their horses were ferried from Cyprus to a staging area on the island of Ruad, a mile off the coast of Tortosa.[183][186] From there, they had a certain amount of success attacking Tortosa (some sources say they engaged in raids, others that they captured the city), but when the hoped-for Mongol reinforcements were delayed (sources differ on whether the delay was caused by weather or illness), the Crusaders had to retreat to Ruad.[187][188] A few months later, in February 1301, the Mongols did arrive with a force of 60,000, but could do little else than engage in some raids around Syria, before they had to again withdraw:

"That year [1300], a message came to Cyprus from Ghazan, king of the Tatars, saying that he would come during the winter, and that he wished that the Franks join him in Armenia (...) Amalric of Lusignan, Constable of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, arrived in November (...) and brought with him 300 knights, and as many or more of the Templars and Hospitallers (...) In February a great admiral of the Tatars, named Cotlesser, came to Antioch with 60,000 horsemen, and requested the visit of the king of Armenia, who came with Guy of Ibelin, Count of Jaffa, and John, lord of Giblet. And when they arrived, Cotelesse told them that Ghazan had met great trouble of wind and cold on his way. Cotlesse raided the land from Haleppo to La Chemelle, and returned to his country without doing more".

— Le Templier de Tyre, Chap 620-622[189]

In mid-1301, the Egyptian Mamluks started besieging the Crusader garrison on Ruad Island.

Campaign of winter 1301-1302

Plans for combined operations were again made for the following winter offensive. A letter has been kept from Molay to Edward I, and dated April 8th, 1301, informing him of the troubles encountered by Ghazan, but announcing that Ghazan was supposed to come in Autumn:

"And our convent, with all our galleys and ships, transported itself to the island of Tortosa, in order to wait for the army of Ghazan and his Tatars."

— Jacques de Molay, letter to Edward I, April 8th, 1301.[191]

And in a letter to the king of Aragon a few months later:

"The king of Armenia sent his messengers to the king of Cyprus to tell him (...) that Ghazan was now close to arriving on the lands of the Sultan with a multitude of Tatars. And we, learning this, have the intention to go on the island of Tortosa where our convent has been stationed with weapons and horses during the present year, causing great devastation on the littoral, and capturing many Sarassins. We have the intention to get there and settle there, to wait for the Tatars."

— Jacques de Molay, letter to the king of Aragon, 1301.[192]

But this time again Ghazan did not appear with his troops.

Campaign of winter 1302-1303

On April 12th, 1302, Ghazan sent a letter and an embassy to Pope Boniface VIII, apparently in answer to an encouraging letter by the latter suggesting Western troops would be dispatched for the 1302/1303 offensive.[193]

"We for our part, are making our preparations. You too should prepare your troops, send word to the rulers of the various nations and not fail to keep the rendezvous. Heaven willing, we shall make the great work [i.e. the war. against the Mamelukes] our sole aim."

— Letter from Ghazan to Pope Boniface VIII, 1302.[194]

Ghazan's ambassadors stayed at the court of Charles II of Anjou. When they returned to Persia after April 27th, 1303, they were accompanied by Gualterius de Lavendel, as embassador of Charles II to Ghazan.[195]

Loss of Ruad

Meanwhile, the siege of Ruad continued. The small island was garrisonned by 120 knights, 500 bowmen and 400 Syrian helpers, under the Templar Maréchal (Commander-in-Chief) Barthélemy de Quincy. The Crusaders, who had no source of fresh water, were able to hold out for nearly a year, but finally had to surrender on September 26th, 1302, following a promise of safe conduct.[196] The promise was not honoured, and all the bowmen and Syrian helpers were killed, and the Templar knights sent to Cairo prisons.[197]

The remaining Templars from Cyprus continued making raids on the Syrian coast in early 1303, and ravaged the city of Damour, south of Beyrouth. As they had lost Ruad, though, they were not capable of providing important troops.[198]

Defeat of Shaqhab

In 1303, the Mongols appeared in greater strength (about 80,000), but they were defeated at Homs on March 30, 1303, and at the decisive Battle of Shaqhab, south of Damas, on April 21, 1303.[198] It is considered to be the last major Mongol invasion of Syria.[199] Also in 1303, Ghazan had again sent a letter to Edward I, in the person of Buscarello de Ghizolfi, reinterating Hulagu's promise that they would give Jerusalem to the Franks in exchange for help against the Mamluks.[200] But Ghazan died on May 10, 1304, and dreams of a rapid reconquest of the Holy Land were destroyed.

New attempts at a joint Crusade (1305-1313)

Oljeitu, also named Mohammad Khodabandeh, was the great-grandson, September 2007 {{citation}}: Missing or empty |title= (help) of the Ilkhanate founder Hulagu, and brother and successor of Mahmud Ghazan. His Christian mother baptized him as a Christian and gave him the name Nicholas [citation needed]. In his youth he at first converted to Buddhism and then to Sunni Islam together with his brother Ghazan. He then changed his first name to the Islamic name Muhammad. In April 1305, Oljeitu sent letters to the French king Philip the Fair,[201] the French Pope Clement V, and Edward I of England. After his predecessor Arghun, he offered a military collaboration between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks. He also explained that internal conflicts between the Mongols were over:

"Now all of us, Timur Khagan, Tchapar, Toctoga, Togba and ourselves, main descendants of Gengis-Khan, all of us, descendants and brothers, are reconciled through the inspiration and the help of God. So that, from Nangkiyan (China) in the Orient, to Lake Dala our people is united and the roads are open."

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.[202]

Relations were quite warm: in 1307, the Pope named John of Montecorvino the first Archbishop of Khanbalik and Patriarch of the Orient.[203] A Mongol embassy arrived in Poitiers to see the Pope in 1307.[204]

As soon as he became Pope in November 1305, Clement V ordered studies on the preparation of a new Crusade. On June 6, 1306, he invited the leaders of the Templars and Hospitallers for a consultation on this subject and that of the fusion of the Orders.[205] In 1307 Molay remitted a memorandum for a new Crusade,[206] but later that year King Philip had him and many other French Templars arrested and tried with trumped-up charges, so that Philip could free himself of his financial debts to the Order. In 1312, under pressure from King Philip, Pope Clement formally disbanded the Order, and in 1314, Jacques de Molay was charged with heresy and burned at the stake in Paris.

The Armenian monk Hayton of Corycus also went to visit Pope Clement V in Poitiers, where he wrote his famous "Flor des Histoires d'Orient", a compilation of the events of the Holy Land describing the alliance with the Mongols, and setting recommendations for a new Crusade:

"God has also shown the Christians that the time is right because the Tartars themselves have offered to give help to the Christians against the Saracens. For this reason Gharbanda, King of the Tartars, sent his messengers offering to use all his power to undo the enemies of the Christian land. Thus, at present, the Holy Land might be recovered with the help of the Tartars and the realm of Egypt, easily conquered without peril or danger. And so Christian forces ought to leave for the Holy Land without any delay.

— Hayton, Flor des Estoires d'Orient, Book IV.[207]

European nations prepared a crusade, but were delayed. In the meantime Oljeitu launched a last campaign against the Mamluks (1312-13), in which he was unsuccessful. A settlement with the Mamluks would only be found when Oljeitu's son signed the Treaty of Aleppo with the Mamluks in 1322.[208]

Last contacts (1322)

In 1320, the Egyptian sultan Naser Mohammed ibn Kelaoun invaded and ravaged Christian Armenian Cilicia. In a letter dated July 1, 1322, Pope John XXII sent a letter from Avignon to the Mongol ruler Abu Sa'id, reminding him of the alliance of his ancestors with Christians, asking him to intervene in Cilicia. At the same time he advocated that he abandon Islam in favor of Christianity. Mongol troops were sent to Cilicia, but only arrived after a ceasefire had been negotiated for 15 years between Constantin, patriarch of the Armenians, and the sultan of Egypt. After Abu Sa'id, relations between Christian princes and the Mongols were totally abandoned.[citation needed][209]

He died without heir and successor. The state lost its status after his death, becoming a plethora of little kingdoms run by Mongols, Turks, and Persians.

Technology exchanges

In these invasions westward, the Mongols brought with them a variety of eastern, often Chinese technologies, which may have been transmitted to the West on these occasions. The original weaknesses of the Mongols in siege warfare (they were essentially a nation of horsemen) were compensated by the introduction of Chinese engineering corps within their army,[210] who therefore had ample contacts with Western lands.

One theory of how gunpowder came to Europe is that it made its way along the Silk Road through the Middle East; another is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century.[211][212] Direct Franco-Mongol contacts occurred as in the 1259-1260 military alliance of the Franks knights of the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law Hetoum I with the Mongols under Hulagu.[57] William of Rubruck, an ambassador to the Mongols in 1254-1255, a personal friend of Roger Bacon, is also often designated as a possible intermediary in the transmission of gunpowder know-how between the East and the West.[213]

Other innovations, such as printing, may have transited through the Mongol routes during that period.

John of Marignolli came back from the Mongols in 1353, with a request from the Great Khan to send more Franscicans to China. Most contacts were interrupted however when the Great Plague started to sweep Europe. The reopening of relations would not occur until the 16th century.[214]

See also

- History of gunpowder

- History of printing

- Al-'Āḍid, the teenaged Muslim caliph in Egypt, who entered into an alliance with the Christians in the 1100s

Notes

- ^ Angus Steward says "Franco-Mongol entente" [1]

- ^ Grousset, p521: "Louis IX et l'Alliance Franco-Mongole", p.653 "Seul Edward I comprit la valeur de l'Alliance Mongole", p.686 "la coalition Franco-Mongole dont les Hospitaliers donnaient l'exemple"

- ^ Demurger, p.147 "Cette expedition avait surtout l'avantage de sceller, par un acte concret l'alliance Mongole", Demurger p.145 "La strategie de l'alliance Mongole en action", "De Molay anime la lutte pour la reconquete de Jerusalem, en s'appuyant sur une alliance avec les Mongols" (Demurger, back cover)

- ^ Prawer, p. 32. "The attempts of the crusaders to create an alliance with the Mongols failed."

- ^ Tyerman, p. 816. "The Mongol alliance, despite six further embassies to the west between 1276 and 1291, led nowhere."

- ^ "There are five Frank states(...): the Kingdom of Jerusalem, (...) the County of Edessa, the County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, but also the Kingdom of Little Armenia", Les Croisades, Origines et consequences, p.77-78

- ^ Between the 11th to the 15th century, the Crusaders were usually called Franks. More broadly the term applied to any persons originating in Catholic western Europe (medieval Middle Eastern history). The term led to derived usage by other cultures, such as Farangi, firang, farang and barang. "The term [Frank] was used by all the populations of the eastern Mediterranean to designate the totality of the Crusaders as well as the settlers" Atlas des Croisades,1996, Jonathan Riley-Smith, ISBN 2862605530

- ^ "On 1 March Kitbuqa entered Damascus at the head of a Mongol army. With him were the King of Armenia and the prince of Antioch. The citizens of the ancient capital of the Caliphate saw for the first time for six centuries three Christian potentates ride in triumph through their streets", Runciman p.307

- ^ Bohemond VI of Antioch, allied of the Mongols, was ruler of both the Principality of Antioch and the County of Tripoli until his death in 1275.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

tyerman-816was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Weatherford, p. 58

- ^ "The Keraits, who were a semi-nomadic people of Turkish origin, inhabited the country round the Orkhon river in modern Outer Mongolia. Early in the eleventh century their ruler had been converted to Nestorian Christianity, together with most of his subjects; and the conversion brought the Keraits into touch with the Uighur Turks, amongst whom were many Nestorians", Runciman, p.238

- ^ "In 1196, Gengis Khan succeeded in the unification under his authority of all the Mongol tribes, some of which had been converted to Nestorian Christianity" "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", p.74

- ^ Weatherford, pp. 160-161

- ^ "In 1196, Gengis Khan succeeded in the unification under his authority of all the Mongol tribes, some of which had been converted to Nestorian Christianity" "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", p.74

- ^ "Early in 1253 a report reached Acre that one of the Mongol princes, Sartaq, son of Batu, had been converted to Christianity", Runciman, p.280

- ^ a b c "Kitbuqa, as a Christian himself, made no secret of his sympathies", Runciman, p.308

- ^ Under Mongka "The chief religious influence was that of the Nestorian Christians, to whom Mongka showed especial favour in memory of his mother Sorghaqtani, who had always remained loyal to her faith" Runciman, p. 296

- ^ Maalouf, p. 242-243

- ^ Foltz, p.111

- ^ Foltz, p.112

- ^ a b c d Adam Knobler (Fall 1996). "Pseudo-Conversions and Patchwork Pedigrees: The Christianization of Muslim Princes and the Diplomacy of Holy War". Journal of World History. 7 (2): 181–197.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ Regesta Honorii Papae III, no 1478, I, p.565. Quoted in Runciman, p.246

- ^ Runciman, p.249

- ^ Runciman, p.250

- ^ Runciman, p.253

- ^ Runciman, p.256

- ^ Runciman, p.254

- ^ Sharan Newman, "Real History Behind the Templars" p. 174, about Grand Master Thomas Berard: "Under Genghis Khan, they [the Mongols] had already conquered much of China and were now moving into the ancient Persian Empire. Tales of their cruelty flew like crows through the towns in their path. However, since they were considered "pagans" there was hope among the leaders of the Church that they could be brought into the Christian community and would join forces to liberate Jerusalem again. Franciscan missionaries were sent east as the Mongols drew near."

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, "The Crusades"

- ^ David Wilkinson, Studying the History of Intercivilizational Dialogues [2]

- ^ Quoted in Michaud, Yahia (Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies) (2002). Ibn Taymiyya, Textes Spirituels I-XVI". Chap XI

- ^ Muncinis, p.259

- ^ David Wilkinson, Studying the History of Intercivilizational Dialogues [3]

- ^ Muncinis, p.259

- ^ Grousset

- ^ Peter Jackson (July 1980). "The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260". The English Historical Review. 95 (376): 481–513.

- ^ Grousset, p.523

- ^ The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville

- ^ Runciman, p.260

- ^ "The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville", Chap. V, Jean de Joinville.The Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville

- ^ Runciman, pp. 279-280

- ^ Runciman, p.380

- ^ Weatherford, pp. 172-173

- ^ J. Richard, 1970, p. 202., Encyclopedia Iranica, [4]

- ^ Weatherford, p. 138. "Subodei made the country a vassal state, the first in Europe, and it proved to be one of the most loyal and supportive Mongol vassals in the generations ahead."

- ^ According to the medieval historian William of Tyre, Hetoum I himself visited the court of Mangu Khan at Karakorum from 1254 to 1255. - >Guillaume de Tyr, Chap. II

- ^ "Bohemond VI etait present a Baghdad en 1258" Demurger, p.55

- ^ Grousset, p.574, mentionning the account of Kirakos, Kirakos, #12

- ^ "After this, [the Mongols] convened a great assembly of the old and new cavalry of the Georgians and Armenians and went against the city of Baghdad with a countless multitude." Grigor of Akner's History of the Nation of Archers, Chap 12, circa 1300

- ^ "The Georgian troops, who had been the first to break through the walls, were particularly fiercest in their destruction" Runciman, p.303

- ^ Maalouf, p. 243

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.306

- ^ Foltz, p.123

- ^ "The Near East was never again to dominate civilization", Runciman, p.304

- ^ Saudi Aramco World "The Battle of Ain Jalut"

- ^ a b Grousset, p. 581

- ^ "On 1 March Kitbuqa entered Damascus at the head of a Mongol army. With him were the King of Armenia and the Prince of Antioch. The citizens of the ancient capital of the Caliphate saw for the first time for six centuries three Chrsitian potentates ride in triumph through their streets", Runciman, p.307

- ^ "The king of Armenia and the Prince of Antioch went to the army of the Tatars, and they all went off to take Damascus".|Gestes des Chiprois, Le Templier de Tyr. "Le roy d'Arménie et le Prince d'Antioche alèrent en l'ost des Tatars et furent à prendre Damas". Quoted in "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p586

- ^ Atlas des Croisades, p.108

- ^ "Subsequently, Hulegu sent presents to [sent for, oe41] the duke of Antioch [Bohemond VI] who was a relative of the King of Armenia [son-in-law of the King of Armenia, oe41], and ordered that all the districts [g50] of his kingdom which the Saracens had held be returned to him. He also bestowed many other favors on him." Fleur des Histoires d'Orient, Chap.29

- ^ Runciman, p.306

- ^ Online Reference Book for Medieval studies

- ^ Runciman, p.307, "Bohemond was excomunicated by the Pope for this alliance (Urban IV, Registres, 26 May 1263

- ^ Runciman, p.310

- ^ "It happened that some men from Sidon and Belfort gathered together, went to the Saracens' villages and fields, looted them, killed many Saracens and took others into captivity together with a great deal of livestock. A certain nephew of Kit-Bugha who resided there, taking along but few cavalry, pursued the Christians who had done these things to tell them on his uncle's behalf to leave the booty. But some of the Christians attacked and killed him and some other Tartars. When Kit-Bugha learned of this, he immediately took the city of the Sidon and destroyed most of the walls [and killed as many Christians as he found. But the people of Sidon fled to an island, and only a few were slain. oe43]. Thereafter the Tartars no longer trusted the Christians, nor the Christians the Tartars." Fleur des Histoires d'Orient, Chap. 30

- ^ Runciman, p.309

- ^ Runciman, p.307

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica article

- ^ Runciman, p.312

- ^ According to the 13th century historian Kirakos, many Armenians and Georgians were also fighting in the ranks of Kitbuqa. - "Among Ket-Bugha's warriors were many Armenians and Georgians who were killed with him" Kirikos, Chap. 62

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica article

- ^ Runciman, p.313

- ^ In 1262, the king of Armenia went to the Mongols and again obtained their intervention to deliver the city. - "In the year 1262, the sultan Bendocdar of Babiloine, who had taken the name of Melec el Vaher, put the city of Antioch under siege, but the king of Armenia went to see the Tatars and had them come, so that the Sarazins had to leave the siege and return to Babiloine.". Original French:"Et en lan de lincarnasion .mcc. et .lxii. le soudan de Babiloine Bendocdar quy se fist nomer Melec el Vaher ala aseger Antioche mais le roy dermenie si estoit ale a Tatars et les fist ehmeuer de venir et les Sarazins laiserent le siege dantioche et sen tornerent en Babiloine."Guillame de Tyr "Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum" #316

- ^ "Grousset, p565

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.565

- ^ Runciman, 325-327

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.650

- ^ Runciman, p.320

- ^ Runciman, p.337

- ^ Grousset, p.650

- ^ Runciman, p334

- ^ Runciman, p330-331

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.644

- ^ Grousset, p.647

- ^ a b Runciman, p.332

- ^ Hindley, pp. 205-206

- ^ Nicolle, p. 47

- ^ Tyerman, p. 818

- ^ Grousset, p.656

- ^ "Edward was horrified at the state of affairs in Outremer. He knew that his own army was small, but he hoped to unite the Christians of the East into a formidable body and then to use the help of the Mongols in making an effective attack on Baibars", Runciman, p.335

- ^ a b Grousset, p.653.

- ^ Runciman, p.336

- ^ "Et revindrent en Acre li message que mi sire Odouart et la Crestiente avoient envoies as Tartars por querre secors; et firent si bien la besoigne quil amenerent les Tartars et corurent toute la terre dantioche et de Halape de Haman et de La Chamele jusques a Cesaire la Grant. Et tuerent ce quil trouverent de Sarrazins", Estoire d'Eracles, Chap XIV

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, p.653

- ^ a b c Runciman, p.336

- ^ a b Hindley, pp. 207-208

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

tyerman-813was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Runciman, p.337