Hamlet: Difference between revisions

→Date and texts: Found many 1599 references. This is one. (Shapiro - Columbia University) |

→Date and texts: Act & scene divisions |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Another theory is that the Q1 text is an abridged version of the full length play intended especially for traveling productions (the aforementioned university productions, in particular.) Kathleen Irace espouses this theory in her New Cambridge edition, "The First Quarto of Hamlet." The idea that the Q1 text is not riddled with error, but is in fact a totally viable version of the play has led to several recent Q1 productions (perhaps most notably, Tim Sheridan and Andrew Borba's 2003 production at the Theatre of NOTE in Los Angeles, for which Ms. Irace herself served as [[dramaturge]]).<ref name="arden">Thompson and Taylor (2007).</ref> |

Another theory is that the Q1 text is an abridged version of the full length play intended especially for traveling productions (the aforementioned university productions, in particular.) Kathleen Irace espouses this theory in her New Cambridge edition, "The First Quarto of Hamlet." The idea that the Q1 text is not riddled with error, but is in fact a totally viable version of the play has led to several recent Q1 productions (perhaps most notably, Tim Sheridan and Andrew Borba's 2003 production at the Theatre of NOTE in Los Angeles, for which Ms. Irace herself served as [[dramaturge]]).<ref name="arden">Thompson and Taylor (2007).</ref> |

||

Shekespeare's plays are traditionally divided into five acts. However, in the case of Hamlet, none of the early texts makes that division, and the usual organisation of acts and scenes derives from a quarto which was not published until 1676. Modern editors generally follow this traditional division, but do not consider it satisfactory: its chief weakness being an act-break upon Hamlet lugging Polonius' body out of his mother's bedchamber (Act 3 Scene 4), after which point the scene appears to be contiuning.<ref>Thompson and Taylor (2006) pp.543-552</ref> |

|||

Some contemporary scholarship is moving away from the ideal of the "full text," supposing its inapplicability to the case of ''Hamlet.'' The Arden Shakespeare's 2006 publication of different texts of ''Hamlet'' in different volumes is perhaps the best evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.<ref name="arden"/> |

Some contemporary scholarship is moving away from the ideal of the "full text," supposing its inapplicability to the case of ''Hamlet.'' The Arden Shakespeare's 2006 publication of different texts of ''Hamlet'' in different volumes is perhaps the best evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.<ref name="arden"/> |

||

Revision as of 18:16, 21 October 2007

Hamlet is a tragedy and revenge play by William Shakespeare. It is one of his best-known works, one of the most-quoted writings in the English language[1] and is universally included on lists of the world's greatest books.[2] Hamlet has been called "Shakespeare's greatest play," [3] and has been one of his most performed, topping, for example, the Royal Shakespeare Company's list since 1879.[4] With 4,042 lines and 29,551 words, Hamlet is also Shakespeare's longest play.[5]

Hamlet is based on a Danish legend recorded by Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum. This legend was translated into French by François de Belleforest in his Histoires Tragiques (1570). Shakespeare is thought to have borrowed much of his plot from a now-lost play referred to today as the Ur-Hamlet, the first version of the story known to have a ghost in it. Shakespeare's Hamlet also bears many similarities to Belleforest's French translation, but whether he took these elements directly from the French, or indirectly through the Ur-Hamlet or some other source, is unknown. The play was written around 1599/1600. Three different early texts are authoritative, known as the First Quarto, Second Quarto, and First Folio, each of which have lines, and even scenes, missing from others.

One of the main questions scholars have asked is why Prince Hamlet, the main character, waits so long to exact revenge on Claudius for his father's death. Some scholars see his delay as a plot device—if he kills Claudius quickly, the plot is cut short. Others see it as a response to complex philosophical and ethical issues surrounding revenge in Shakespeare's day. Another common question is whether Hamlet is truly mad, or whether he is merely feigning his madness. Since Freud, psychoanalytic critics have asked whether Hamlet has an Oedipus complex. Feminist critics have called attention to Ophelia and Gertrude's experiences within the play.

Hamlet was one of Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime. The role of Hamlet was probably first performed by Richard Burbage, the leading tragedian of The Lord Chamberlain's Men.[6] It was revived during the Restoration period and has been popular ever since. Several movie adaptations have been made, beginning with silent films in the early 20th Century.

Sources

The story of the prince who plots revenge on his uncle, the current king, for killing his father, the former king, is an old one. Many of the story elements—the prince's feigned madness, his mother's hasty marriage to the usurper, the testing of the prince's madness with a young woman, the prince talking to his mother and killing a hidden spy, his being sent to England with two retainers and substituting their execution for his own—are also part of a medieval tale by Saxo Grammaticus called Vita Amlethi (part of his larger Latin work Gesta Danorum), which was written around 1200 AD. Older written and oral traditions from various cultures influenced Saxo's work. Amleth, as Hamlet is called in his version, probably derived from an oral tale told throughout Denmark and Scandinavia. Scholars have also uncovered references to it in Icelandic legend. Although there is no existing copy of the Icelandic version of the story, Torfaeus, an early Icelandic scholar (born 1636), described parallels to the Icelandic story of Amloi in the Spanish story of the Ambales Saga. This story contains similarities to Shakespeare's Hamlet in Prince Ambales' feigned madness, his accidental killing of the King's counsellor in his mother's bedroom, and the eventual slaying of his uncle.[7]

The two most popular candidates for written works that may have influenced Saxo, however, are the anonymous Scandinavian Saga of Hrolf Kraki and the Roman legend of Brutus, which is recorded in two separate Latin works. In Saga of Hrolf Kraki, there are two sons of the murdered king: Hroar and Helgi, who later take the names Ham and Hráni as a disguise. They spend most of the story in hiding, rather than feigning madness, though Ham does behave in a childlike manner to avoid suspicion at one point. The sequence of events differs from Shakespeare's as well. The Roman story of Brutus focuses on feigned madness, as a man called Lucius changes his name to Brutus ('dull, stupid') and plays the part in order to avoid the fate of his father and brothers. Eventually he slays his family's killer, King Tarquinus. In addition to writing in the Latin language of the Romans, Saxo adjusted the story to meet classical Roman concepts of virtue and heroism. A reasonably accurate version of Saxo's story was translated into French in 1570 by François de Belleforest in his Histoires Tragiques.[8] Belleforest embellished Saxo's text substantially, nearly doubling the total length. His version added descriptions of the hero's melancholy.[7]

Scholars have speculated about the ultimate source of the 'hero as fool' story, but no definitive candidate has emerged. Given the many different cultures from which Hamlet-like legends come (Roman, Spanish, Scandinavian and Arabic), a few have guessed that the story may be generally Indo-European in origin.[7]

Shakespeare's main source is believed to be an earlier play—now lost—known today as the Ur-Hamlet. Possibly written by Thomas Kyd, this earlier Hamlet play was in performance by 1589 and seems to have been the first to include a ghost in the story.[9] Shakespeare's company, the Chamberlain's Men, may have purchased that play and performed a version, which Shakespeare reworked, for some time.[7] Since no copy of the Ur-Hamlet has survived, however, it is impossible to compare its language and style with the known works of any candidate for its authorship; consequently, there is no direct evidence that Kyd wrote it, nor is there any evidence that the play was an early version by Shakespeare himself. This latter idea—that Shakespeare wrote Hamlet earlier than the generally accepted date, and revised it on numerous occasions—has attracted some support, while others dismiss it as speculation.[10]

Scholars are unable to assert with any confidence how much material Shakespeare took from the Ur-Hamlet, how much from Belleforest or Saxo, and how much from other contemporary sources (such as Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy). There is no clear evidence that Shakespeare made any direct references to Saxo's version, although its Latin text was widely available at the time. There are, however, elements of Belleforest's version that appear in Shakespeare's play but not in Saxo's story. Whether Shakespeare took these from Belleforest directly or through the Ur-Hamlet remains unclear.[7]

It is clear, though, that several elements changed somewhere between Belleforest's and Shakespeare's versions. For one, unlike Saxo and Belleforest, Shakespeare's play has no all-knowing narrator, with the consequence that the audience is invited to draw its own conclusions about characters' motives. The traditional story also encompasses several years, while Shakespeare's covers a few weeks. Belleforest's version details Hamlet's plan for revenge, while in Shakespeare's play Hamlet has no apparent plan. Shakespeare also added some elements that located the action in 15th-century Christian Denmark, rather than a pagan, medieval setting. Elsinore, for example, would have been familiar to Elizabethan England, as a new castle had recently been built there, and Wittenberg, Hamlet's university, was widely known for its protestant teachings.[7] Other elements of Shakespeare's Hamlet that are not found in medieval versions include the secrecy that surrounds the old king's murder, the inclusion of Laertes and Fortinbras (who offer parallels to Hamlet), the testing of the king via a play, and Hamlet's tragic death at the moment he gains his revenge.[11]

Scholars have debunked the idea that Hamlet is in any way connected with Shakespeare's only son, Hamnet Shakespeare, who died at age eleven. Hamlet is too obviously connected to legend and the name Hamnet was quite popular at the time.[7]

Date and texts

The Register of the Stationers' Company records an entry for Hamlet on July 26, 1602, which indicates that the play was "latelie Acted by the Lo: Chamberleyne his servantes." This establishes a later limit for the dating of the play. Hamlet's frequent allusions to Julius Caesar, which has been dated to mid-1599, help to establish an earlier limit.[12] "Any dating of Hamlet must be tentative", Edwards cautions.[13] Many scholars date the play between 1599 and 1601,[14]while some scholars have argued for a date as early as 1589.[15]

The "textual problem" of Hamlet involves three crucial early versions of the play:[16]

- In 1603, the booksellers Nicholas Ling and John Trundell published the so-called "bad" first quarto (referred to as Q1); Valentine Simmes printed this edition. Q1 contains just over half of the text of the later second quarto.

- In 1604, Nicholas Ling published the second quarto (referred to as Q2); James Roberts printed this edition. Some copies of Q2 are dated 1605, which may indicate a second impression; consequently, Q2 is often dated "1604/5". Q2 is the longest of the three editions, although it omits 85 lines that are found in F1 (these passages were most likely left out to avoid offending the queen of James I, who was from Denmark).[17]

- In 1623, Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard published the First Folio (referred to as F1), the first edition of Shakespeare's Complete Works.[18]

Subsequent folios and quartos (John Smethwick's Q3, Q4, and Q5, 1611–37) are considered derivatives of these first three editions. Q1 itself has been viewed with scepticism; in practice, editors tend to rely upon Q2 and F1.[19]

Early editors of Shakespeare's works, starting with Nicholas Rowe (1709) and Lewis Theobald (1733), combined material from the two earliest sources of Hamlet then known, Q2 and F1. Each text contains some material the other lacks, and there are many minor differences in wording, so that only a little more than 200 lines are identical between them. Typically, editors have taken an approach of combining, "conflating," the texts of Q2 and F1, in an effort to create an inclusive text as close as possible to the ideal Shakespeare original. Theobald's version became standard for a long time.[20] Certainly, the "full text" philosophy that he established has influenced editors to the current day. Although many modern editors have done essentially the same thing Theobald did, also using, for the most part, the 1604/5 quarto and the 1623 folio texts, two recent editions edit separate versions, adding the additional lines in an appendix.[21]

The discovery of Q1 in 1823, when its existence had not even been suspected earlier, caused considerable interest and excitement, while also raising questions. The deficiencies of the text were recognized immediately—Q1 was instrumental in the development of the concept of a Shakespeare "bad quarto."[22] Yet Q1 also has its value: it contains stage directions which reveal actual stage performance in a way that Q2 and F1 do not, and it contains an entire scene (usually labeled IV,vi) that is not in either Q2 or F1. Also, Q1 is useful simply for comparison to the later publications. At least 28 different productions of the Q1 text since 1881 have shown it eminently fit for the stage. Q1 is generally thought to be a "memorial reconstruction" of the play as it may have been performed by Shakespeare's own company, although there is disagreement whether the reconstruction was pirated, or authorized. It is considerably shorter than Q2 or F1, apparently because of significant cuts for stage performance. It is thought that one of the actors playing a minor role (Marcellus, certainly, perhaps Voltemand as well) in the legitimate production was the source of this version.[23]

Another theory is that the Q1 text is an abridged version of the full length play intended especially for traveling productions (the aforementioned university productions, in particular.) Kathleen Irace espouses this theory in her New Cambridge edition, "The First Quarto of Hamlet." The idea that the Q1 text is not riddled with error, but is in fact a totally viable version of the play has led to several recent Q1 productions (perhaps most notably, Tim Sheridan and Andrew Borba's 2003 production at the Theatre of NOTE in Los Angeles, for which Ms. Irace herself served as dramaturge).[24]

Shekespeare's plays are traditionally divided into five acts. However, in the case of Hamlet, none of the early texts makes that division, and the usual organisation of acts and scenes derives from a quarto which was not published until 1676. Modern editors generally follow this traditional division, but do not consider it satisfactory: its chief weakness being an act-break upon Hamlet lugging Polonius' body out of his mother's bedchamber (Act 3 Scene 4), after which point the scene appears to be contiuning.[25]

Some contemporary scholarship is moving away from the ideal of the "full text," supposing its inapplicability to the case of Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare's 2006 publication of different texts of Hamlet in different volumes is perhaps the best evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.[24]

Characters

- Hamlet is the Prince of Denmark. Son to the late, and nephew to the present, king.

- Claudius is the King of Denmark, elected to the throne after the death of his brother, King Hamlet. Claudius has married Gertrude, his brother's widow.

- Gertrude is the Queen of Denmark, and King Hamlet's widow, now married to Claudius, and mother to Hamlet.

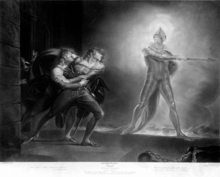

- the Ghost, appears in the exact image of Hamlet's father, the late King Hamlet (Old Hamlet).

- Polonius is Claudius's chief advisor, and the father of Ophelia and Laertes. (This character is called "Corambis" in the First Quarto of 1603.)

- Laertes is the son of Polonius, and has returned to Elsinore Castle after living in Paris.

- Ophelia is Polonius's daughter, and Laertes's sister, who lives with her father at Elsinore Castle.

- Horatio is a good friend of Hamlet, from the university at Wittenberg, who came to Elsinore Castle to attend King Hamlet's funeral.

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are childhood friends and schoolmates of Hamlet, who were summoned to Elsinore by Claudius and Gertrude.

- Fortinbras is the nephew of old King Norway. He is also the son of Fortinbras Sr, who was killed in single combat by Hamlet's father.

- Marcellus, Barnardo, and Francisco are sentinels who help guard Elsinore Castle.

- Voltemand and Cornelius are ambassadors King Claudius sends to old King Norway.

- Reynaldo is Polonius's servant. (This character is called "Montano" in the First Quarto.)

- First Player in a company of Players who arrive at Elsinore.

- the Lad in the Players' company who plays the female characters.

- Other Players of the Players' company.

- a Captain in Fortinbras's army.

- a Gentleman who informs Gertrude of Ophelia's strange behavior.

- Messengers

- Switzers who are Claudius's bodyguards.

- Ladies in waiting to Queen Gertrude.

- Townspeople who are followers of Laertes.

- Sailors (are actually two pirates.)

- Two Clowns, a sexton and a bailiff.

- Yorick, a dead jester, who is honored by Hamlet.

- A Priest (identified as a Protestant cleric, a doctor of divinity, in the Second Quarto.)

- Osric, a courtier (originally named "Ostricke" in the Second Quarto.)

- English Ambassadors

- Lords, ladies, courtiers, servants, guards, and other extras as required.

Synopsis

On a cold winter night, two sentries try to convince the sceptical student Horatio that they have seen the ghost of the recently-deceased King Hamlet, when the ghost suddenly appears. Horatio tries to question it but it stalks away. He proposes they tell the old king's son, Hamlet.

Claudius, the new king, proclaims an end to the official mourning for his brother, in light of his marriage to Gertrude, his brother's queen. Claudius and Gertrude try to persuade Hamlet to abandon his melancholy and not to return to university in Wittenburg. Hamlet promises to try to obey his mother. Left alone, he vents his frustration at her hasty remarriage. He is interrupted by Horatio and the sentries, who inform him of the portentous apparition.

That night, Hamlet speaks to his father's ghost, who reveals that he was poisoned by Claudius. He commands Hamlet to avenge his murder. Hamlet vows to do so and swears his companions to secrecy. He decides to disguise his true intents by feigning madness.

Ophelia reports to her father, the King's counsellor Polonius, how Hamlet came to her bedroom in a fit of madness. Polonius deduces an "ecstasy of love" is to blame. Meanwhile, Claudius enlists two of Hamlet's school-friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to discover the cause of Hamlet's madness. Polonius puts his theory to Claudius and Gertrude.

Hamlet greets Rozencrantz and Guildenstern warmly, but soon discerns their duplicity. He professes a disaffection with the world, for which Rozencrantz recommends a troupe of actors, who soon arrive. Hamlet solicits a passionate performance from one of them. Alone, he reflects on the feigned passion of the actor and his own failure to act. Uncertain whether the ghost was genuine, he resolves to confirm his uncle's guilt by observing his response to the staging of a play, which he later calls The Mousetrap.

Claudius agrees to attend the play, but first he and Polonius hide themselves, to spy on Hamlet with Ophelia. Thinking he is alone, Hamlet reflects on his predicament, until Ophelia alerts him to her presence. Hamlet berates her for her immodesty and dismisses her to a nunnery, causing her great distress. The king decides to send Hamlet to England, but Polonius persuades him first to allow the Queen to try to discover the cause of Hamlet's distemper.

Hamlet directs the actors' preparations. The court assembles and the play begins; Hamlet offers a running commentary throughout. When the action shows a king poisoned, Claudius rises abruptly and leaves, from which Hamlet deduces his guilt.

Hamlet is summoned to his mother's bedchamber. On his way, he discovers Claudius praying. Poised to kill, Hamlet hesitates. He reasons that to kill Claudius in prayer would send him to heaven.

Hamlet confronts his mother in her chamber. Gertrude panics and cries out. Polonius, hiding behind a tapestry, responds, prompting Hamlet to stab wildly in that direction. Hoping it was the king, he discovers Polonius' corpse. Hamlet directs a sustained accusation at Gertrude, who admits some guilt. The ghost appears to bid him treat her gently and to spur him on to his revenge. Unable to see the apparition, Gertrude takes Hamlet's behaviour for a sign of madness. Hamlet drags the corpse away.

Claudius sends Hamlet to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who carry a secret request for his execution. Having watched the army of Fortinbras (nephew to the Norwegian king) pass through, Hamlet reflects on his own inaction.

Ophelia wanders the court in grief-induced madness, singing incoherently. Laertes (Polonius’s son recently returned from abroad), seeking revenge for his father's murder, bursts into the royal chamber at the head of a rabble that clamours for him to be king. The sight of his sister, Ophelia, in her distracted state further incenses him. Claudius convinces Laertes that Hamlet is to blame. Learning of Hamlet's escape and return to Denmark, Claudius proposes a rigged fencing-match, using poisioned rapiers, as a surreptitious vehicle for Laertes' revenge. Gertrude interrupts to report that Ophelia has drowned.

Two clowns debate the legality of Ophelia's apparent suicide, whilst digging her grave. Hamlet arrives with Horatio and banters with a gravedigger, who unearths the skull of a jester from Hamlet's childhood, Yorick. A funeral procession approaches. On hearing that it is Ophelia's and seeing Laertes leap into her grave, Hamlet advances and the two grapple.

Back at Elsinore, Hamlet tells Horatio the story of his escape and how he arranged the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. A courtier informs Hamlet of the King's wager on a fencing match with Laertes. Hamlet agrees to participate.

The court enters, ready for the match. Claudius orders cups of wine prepared, one of which he has poisoned. During the bout, Gertrude drinks from the poisoned cup. Laertes succeeds in piercing Hamlet with a poisoned blade, but, in the struggle, is wounded by it himself. Gertrude dies. With his dying breath Laertes reveals the king’s plot. Hamlet kills Claudius. Hamlet and Laertes forgive each other as Laertes dies. Before succumbing to the poison, Hamlet names Fortinbras as heir. As Fortinbras arrives, Horatio promises to recount the tale. Fortinbras orders Hamlet’s body borne off in honour.

Analysis and criticism

Critical history

From the beginning, Hamlet has aroused questions from critics regarding Hamlet's supposed madness and melancholy. Critics in Shakespeare's day focused on these themes in their understanding of the play, which at the time was portrayed more violently than in later times.[26][27] Analysts of the Restoration period disliked the play's lack of unity in time and space,[28] as well as the perceived immodest madness of Ophelia in the flower scene.[29] Views of the play improved, however, in the eighteenth century. Critics viewed Hamlet as a hero, saying that he was a pure, brilliant young man thrust into unfortunate circumstances.[26] Psychological and mystical readings increased with the rise of Gothic literature in this period. Hamlet's madness and the ghost both attracted a lot of attention.[30] The Romantic period viewed Hamlet as the epitome of a tragic fall.[31] Nineteenth-century critics focused more heavily on the individual drive and internal struggle of Prince Hamlet, seeing him as more of a political rebel and intellectual than an over-sensitive melancholy. This period also introduced questions as to why Hamlet delays in killing the King, which critics of earlier periods had largely ignored as a mere plot device.[26] In the twentieth century, criticism branched in several directions. Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones theorized that Hamlet had an unresolved Oedipus Complex, and feminist critics introduced new points of view towards Gertrude and Ophelia. Most recently, New Historicist critics have begun looking at the play in its historical context, attempting to piece together the backdrop that created the play.[26]

Dramatic structure

In creating Hamlet, Shakespeare broke several rules, one of the largest being the rule of action over character. In his day, plays were usually expected to follow the advice of Aristotle in his Poetics, which declared that a drama should not focus on character so much as action. The highlights of Hamlet, however, are not the action scenes, but the soliloquies, wherein Hamlet reveals his motives and thoughts to the audience. Also, unlike Shakespeare's other plays, there is no strong subplot; all plot forks are directly connected to the main vein of Hamlet struggling to gain revenge. The play is full of seeming discontinuities and irregularities of action. At one point, Hamlet is resolved to kill Claudius: in the next scene, he is suddenly tame. Scholars still debate whether these odd plot turns are mistakes or intentional additions to add to the play's theme of confusion and duality.[32]

Language

Much of the play's language is in the elaborate, witty language expected of a royal court. This is in line with Baldassare Castiglione's work, The Courtier (published in 1528), which outlines several courtly rules, specifically advising servants of royals to amuse their rulers with their inventive language. Osric and Polonius seem to especially respect this suggestion. Claudius' speech is full of rhetorical figures, as is Hamlet's and, at times, Ophelia's, while Horatio, the guards, and the gravediggers use simpler methods of speech. Claudius demonstrates an authoritative control over the language of a King, referring to himself in the first person plural, and using anaphora mixed with metaphor that hearkens back to Greek political speeches. Hamlet seems the most educated in rhetoric of all the characters, using anaphora, as the king does, but also asyndeton and highly developed metaphors, while at the same time managing to be precise and unflowery (as when he explains his inward emotion to his mother, saying "But I have that within which passes show, / These but the trappings and the suits of woe."). His language is very self conscious, and relies heavily on puns. Especially when pretending to be mad, Hamlet uses puns to reveal his true thoughts, while at the same time hiding them. Psychologists have since associated a heavy use of puns with schizophrenia.[33]

Hendiadys is one rhetorical type found in several places in the play, as in Ophelia's speech after the nunnery scene ("Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state" and "I, of all ladies, most deject and wretched" are two examples). Many scholars have found it odd that Shakespeare would, seemingly arbitrarily, use this rhetorical form throughout the play. Hamlet was written later in his life, when he was better at matching rhetorical figures with the characters and the plot than early in his career. Wright, however, has proposed that hendiadys is used to heighten the sense of duality in the play.[34]

Hamlet's soliloquies have captured the attention of scholars as well. Early critics viewed such speeches as To be or not to be as Shakespeare's expressions of his own personal beliefs. Later scholars, such as Charney, have rejected this theory saying the soliloquies are expressions of Hamlet's thought process. During his speeches, Hamlet interrupts himself, expressing disgust in agreement with himself, and embellishing his own words. He has difficulty expressing himself directly, and instead skirts around the basic idea of his thought. Not until late in the play, after his experience with the pirates, is Hamlet really able to be direct and sure in his speech.[35]

Contexts

Religious

The play makes several references to both Catholicism and Protestantism, the two most powerful theological forces of the time. The Ghost describes himself as being in purgatory, and as having died without receiving his last rites. This, along with Ophelia's burial ceremony, which is uniquely Catholic, make up most of the play's Catholic connections. Some scholars have pointed that revenge tragedies were traditionally Catholic, possibly because of their sources: Spain and Italy, both Catholic nations. Scholars have pointed out that knowledge of the play's Catholicism can reveal important paradoxes in Hamlet's decision process. According to Catholic doctrine, the strongest duty is to God and family. Hamlet's father being killed and calling for revenge thus offers a contradiction: does he avenge his father and kill Claudius, or does he leave the vengeance to God, as his religion requires?[36]

The play's Protestantism lies in its location in Denmark, a Protestant country in Shakespeare's day, though it is unclear whether the fictional Denmark of the play is intended to mirror this fact. The play does mention Wittenburg, which is where Hamlet is attending university, and where Martin Luther first nailed his 95 theses.[37] One of the more famous lines in the play related to Protestantism is:

“There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be not now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet will it come—the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is't to leave betimes, let be.”[38]

In the First Quarto, the same line reads: “There's a predestinate providence in the fall of a sparrow." Scholars have wondered whether Shakespeare was censored, as the word “predestined” appears in this one Quarto of Hamlet, but not in others, and as censoring of plays was far from unusual at the time.[39] Rulers and religious leaders feared that the doctrine of predestination would lead people to excuse the most traitorous of actions, with the excuse, “God made me do it.” English Puritans, for example, believed that conscience was a more powerful force than the law, due to the new ideas at the time that conscience came not from religious or government leaders, but from God directly to the individual. Many leaders at the time condemned the doctrine, as: “unfit 'to keepe subjects in obedience to their sovereigns” as people might “openly maintayne that God hath as well pre-destinated men to be trayters as to be kings."[40] King James, as well, often wrote about his dislike of Protestant leaders' taste for standing up to kings, seeing it as a dangerous trouble to society.[41] Throughout the play, Shakespeare mixes the two religions, making interpretation difficult. At one moment, the play is Catholic and medieval, in the next, it is logical and Protestant. Scholars continue to debate what part religion and religious contexts play in Hamlet.[42]

Philosophical

Hamlet can be characterized as a philosophical character. He is constantly questioning why the world is the way it is, and seeking to find a mode of life that will give him some sort of guidance. Some of the most prominent philosophical theories in Hamlet are relativism, existentialism, and skepticism. Hamlet expresses a relativist idea when he says to Rosencrantz: "...there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so."[43] The idea that nothing is real except in the mind of the individual finds its roots in the Greek Sophists, who argued that since nothing can be perceived except through the senses, and all men felt and sensed things differently, truth was entirely relative. There was no absolute truth.[44] This same line of Hamlet's also introduces theories of existentialism. A double-meaning can be read into the word "is", which introduces the question of whether anything "is" or can be if thinking doesn't make it so. This is tied into his To be, or not to be speech, where "to be" can be read as a question of existence. Hamlet's contemplation on suicide in this scene, however, is more religious than philosophical. He believes that he will continue to exist after death.[45]

Hamlet is perhaps most affected by the prevailing skepticism in Shakespeare's day in response to the Renaissance's humanism. Humanists living prior to Shakespeare's time had argued that man was godlike, capable of anything. They argued that man was the God's greatest creation. A skepticism toward this attitude is clearly expressed in Hamlet's What a piece of work is a man speech:[46][47]

... this goodly frame, the

earth, seems to me a sterile promontory, this most

excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave

o'erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted

with golden fire, why, it appears no other thing to

me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason!

how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how

express and admirable! in action how like an angel!

in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the

world! the paragon of animals! And yet, to me,

what is this quintessence of dust?

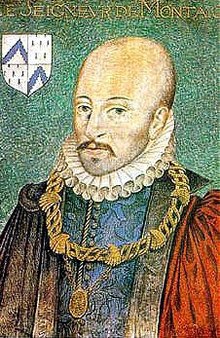

Scholars have pointed out this section's similarities to lines written by Michel de Montaigne in his Essais:

Who have persuaded [man] that this admirable moving of heavens vaults, that the eternal light of these lampes so fiercely rowling over his head, that the horror-moving and continuall motion of this infinite vaste ocean were established, and contine so many ages for his commoditie and service? Is it possible to imagine so ridiculous as this miserable and wretched creature, which is not so much as master of himselfe, exposed and subject to offences of all things, and yet dareth call himself Master and Emperor.

However, rather than being a direct influence on Shakespeare, Montaigne may have merely been reacting to the same general atmosphere of the time, making the source of these lines one of context rather than direct influence.[48][47]

Themes and Motifs

Revenge and Hamlet's delay

Within Hamlet, the stories of five murdered father's sons are told. Three of them are characters: Hamlet, Laertes and Fortinbras, and two are introduced by references to classical stories: Pyrrhus and Brutus. Each of them faces the question of revenge in a different way. For example, Laertes moves quickly to be "avenged most throughly of [his] father," while Fortinbras attacks Poland, rather than the guilty Denmark. Pyrrhus only stays his hand momentarily before avenging his father, Achilles, but Brutus never takes any action in his situation. Hamlet is a perfect balance in the midst of these stories, neither acting quickly nor being completely inactive.[49]

Hamlet struggles to turn his desire for revenge into action, and spends a large portion of the play waiting rather than doing. Scholars have proposed numerous theories as to why he waits so long to kill Claudius. Some say that Hamlet feels for his victim, fearing to strike because he believes that if he kills Claudius he will be no better than him. The story of Pyrrhus, told by one of the acting troupe, for example, shows Hamlet the darker side of revenge, something he does not wish for. Hamlet frequently admires those who are swift to act, such as Laertes, who comes to avenge his father's death, but at the same time fears them for their passion, intensity, and lack of logical thought.[50]

Hamlet's speech in act three, where he chooses not to kill Claudius in the midst of prayer, has taken a central spot in this debate. Scholars have wondered whether Hamlet is being totally honest in this scene, or whether he is rationalizing his inaction to himself. Critics of the Romantic era decided that Hamlet was merely a procrastinator, in order to avoid the belief that he truly desired Claudius' spiritual demise. Later scholars suggested that he refused to kill an unarmed man, or that he felt guilt in this moment, seeing himself as a mirror of the man he wanted to destroy. Historical discoveries, however, assert that Elizabethan ideas of revenge required spiritual and physical destruction for complete justice. Thus, for Hamlet to truly keep the oath he made to his father, he must wait for the right moment, as he explains.[51]

The play is also full of constraint imagery. Hamlet describes Denmark as a prison, and himself as being caught in birdlime. He mocks the ability of man to bring about his own ends, and points out that some divine force molds men's aims into something other than what they intend. Other characters also speak of constraint, such as Polonius, who orders his daughter to lock herself from Hamlet's pursuit, and describes her as being tethered. This adds to the play's description of Hamlet's inability to act out his revenge.[52]

Madness

Hamlet has been compared to the Earl of Essex, who was executed for leading a rebellion against Queen Elizabeth. Essex's situation has been analyzed by scholars for its revelations into Elizabethan ideas of madness in connection with treason as they connect with Hamlet. Essex was largely seen as out of his mind by Elizabethans, and admitted to insanity on the scaffold before his death. Seen in the same context, Hamlet is quite possibly as mad as he is pretending to be, at least in an Elizabethan sense. One of the reasons Hamlet may be so difficult for modern scholars to diagnose is that Shakespeare created him under Elizabethan ideas of madness, making contemporary diagnoses inaccurate. Another explanation of madness in Shakespeare's time was demonic possession, which is altogether possible within the play as well, with its ghost.[53][26]

Other Interpretations

Psychoanalytic

In 1897, in his Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud wrote that Hamlet is based on the title character’s hesitation, and that Hamlet can do anything except take revenge, because he feels a sympathy for Claudius. Freud made this claim in light of his theories about the Oedipus complex, which claimed that all men grow up with an expressed sexual desire toward their mother, and a hatred of their father for coming between them. According to Freud's theory, Hamlet cannot kill Claudius because Claudius has done what Hamlet always dreamed of doing: killing his father in order to take his mother's bed. Meanwhile, Hamlet himself does not know why he has not taken revenge because his desire is suppressed into his unconscious. Since this theory, the 'closet scene' in which Hamlet confronts his mother in private quarters has been portrayed in a sexual light in several performances. Hamlet in these performances is viewed as scolding his mother for having sex with Claudius, while simultaneously wishing (unconsciously) that he could take Claudius' place. Adultery and incest is thus what he simultaneously loves and hates about his mother. Ophelia's madness after her father's death can be read through the Freudian lens as a reaction to the death of her hoped-for lover, her father. Her unrequited love for him suddenly slain is too much for her and she drifts into insanity.[54][55]

Feminist

Carolyn Heilbrun published an essay on Hamlet in 1957 entitled "Hamlet's Mother". In it, she defended Gertrude, arguing that the text never hints that Gertrude knew of Claudius poisoning King Hamlet, a view which has been championed by many feminists.[56] Heilbrun argued that the men who had interpreted the play over the centuries had completely misinterpreted Gertrude, believing what Hamlet said about her rather than the actual text of the play. In this view, no clear evidence suggests that Gertrude was an adulteress. She was merely adapting to the circumstances of her husband's death for the good of the kingdom. Ophelia, also, has been defended by feminists, most notably Elaine Showalter. Ophelia is surrounded by powerful men: her father, brother, and Hamlet. All three disappear: Laertes leaves, Hamlet abandons her, and Polonius dies. Conventional theories had argued that without these three powerful men making decisions for her, Ophelia was driven into madness.[57] Feminist theorists argue that she goes mad with guilt because, when Hamlet kills her father, he has fulfilled her sexual desire to have Hamlet kill her father so they can be together. Showalter points out that Ophelia has become the symbol of the distraught and hysterical woman in modern culture, a symbol which may not be entirely accurate nor healthy for women.[58]

Performance history

Shakespeare's day to the Interregnum

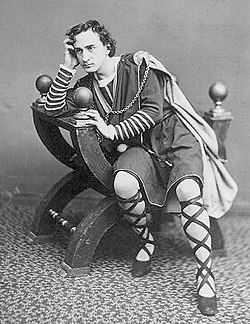

Shakespeare wrote the role of Hamlet for Richard Burbage, chief tragedian of The Lord Chamberlain's Men: an actor with a capacious memory for lines, and a wide emotional range.[6] Hamlet appears to have been Shakespeare's fourth most popular play during his lifetime, eclipsed only by Henry VI Part 1, Richard III and Pericles.[59] Although the story was set many centuries before, at The Globe the play was performed in Elizabethan dress.[60]

Hamlet was acted by the crew of the ship Dragon, off Sierra Leone, in September 1607.[61] Court performances occurred in 1619 and in 1637, the latter on January 24 at Hampton Court Palace.[62] G R Hibbard argues that since Hamlet is second only to Falstaff among Shakespeare's characters in the number of allusions and references to him in contemporary literature, the play must have been performed with a frequency missed by the historical record.[63]

Restoration and 18th century

The play was revived early in the Restoration era: in the division of existing plays between the two patent companies, Hamlet was the only Shakespearean favourite to be secured by Sir William Davenant's Duke's Company.[64] Davenant cast Thomas Betterton in the central role, and he would continue to pay Hamlet until he was 74.[65] David Garrick at Drury Lane produced a version which heavily adapted Shakespeare, saying: "I had sworn I would not leave the stage till I had rescued that noble play from all the rubbish of the fifth act. I have brought it forth without the grave-digger's trick, Osrick, & the fencing match."[66]. The first actor known to have played Hamlet in North America was Lewis Hallam, Jr. in the American Company's production in Philadelphia in 1759.[67]

John Philip Kemble made his Drury Lane dubut as Hamlet, in 1783.[68] His performance was said to be twenty minutes longer than anyone else's and his lengthy pauses led to the cruel suggestion that "music should be played between the words."[69] Sarah Siddons is the first actress known to have played Hamlet,[70] and the part has subsequently often been played by women, to great acclaim. In 1748, Alexander Sumarokov wrote a Russian adaptation focusing on Prince Hamlet as the opposition to Claudius' tyranny: a theme which would pervade Eastern European adaptations into the twentieth century.[71] In the years following America's independence, Thomas Abthorpe Cooper was the young nation's leading tragedian, performing Hamlet (among other plays) at the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia and the Park Theatre in New York. Although chided for "acknowledging acquaintances in the audience" and "inadequate memorisation of his lines", he became a national celebrity.[72]

19th century

In the romantic and early Victorian eras, the highest-quality Shakespearean performances in the United States were tours by leading London actors, including George Frederick Cooke, Junius Brutus Booth, Edmund Kean, William Charles Macready and Charles Kemble. Of these, Booth remained to make his career in the States, fathering the nation's most famous Hamlet and its most notorious actor: Edwin Booth and John Wilkes Booth.[73] Charles Kemble initiated an enthusiasm for Shakespeare in the French: his 1827 Paris performance of Hamlet was viewed by leading members of the Romantic movement, including Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, who particularly admired Harriet Smithson's performance of Ophelia in the mad scenes.[74] Edmund Kean was the first Hamlet to abandon the regal finery usually assiciated with the role in favour of a plain black costume, and to play Hamlet as serious and introspective.[75] The actor-managers of the Victorian era (including Kean, Phelps, Macready and Irving) staged Shakespeare in a grand manner, with elaborate scenery and costumes.[76] In stark contrast, William Poel's production of the first quarto text in 1881 was an early attempt at reconstructing Elizabethan theatre conditions, and was simply set against red curtains.[77][78]

The tendency of the actor-managers to play up the importance of their own central character did not always meet with the critics' approval. Shaw's praise for Forbes-Robertson's performance ends with a sideswipe at Irving: "The story of the play was perfectly intelligible, and quite took the attention of the audience off the principal actor at moments. What is the Lyceum coming to?"[79] Hamlet had toured in Germany within five years of Shakespeare's death,[80] and by the middle of the nineteenth century had become so assimilated into German culture as to spawn Ferdinand Freiligrath's assertion that "Germany is Hamlet"[81] From the 1850s in India, the Parsi theatre tradition transformed Hamlet into folk performances, with dozens of songs added.[82] In the United States, Edwin Booth's Hamlet became a thetrical legend. He was described as "like the dark, mad, dreamy, mysterious hero of a poem... [acted] in an ideal manner, as far removed as possible from the plane of actual life."[83] Booth played Hamlet for 100 nights in the 1864/5 season at the Winter Garden Theatre, inaugurating the era of long-run Shakespeare in America.[84] Sarah Bernhardt played the prince in her popular 1899 London production, and in contrast to the "effeminate" view of the central character which usually lay behind a female casting, she described her character as "manly and resolute, but nonetheless thoughtful... [he] thinks before he acts, a trait indicative of great strength and great spiritual power."[85]

20th century

Apart from some nineteenth-century visits by western troupes, the first professional performance of Hamlet in Japan was Otojiro Kawakami's 1903 Shimpa ("new school theatre") adaptation.[86] Hamlet was successfully translated by Shoyo Tsubouchi who produced a performance in 1911, blending Shingeki ("new drama") and Kabuki styles.[87] This hybrid-genre reached its height in Fukuda Tsuneari's 1955 Hamlet.[88] In 1998, Yukio Ninagawa produced an acclaimed version of Hamlet in the style of Noh theatre, which he took to London.[89]

Hamlet, a political play, is often played with contemporary political overtones: Leopold Jessner's 1926 production at the Berlin Staatstheater portrayed Claudius' court as a parody of the corrupt and fawning court of Kaiser Wilhelm.[90] Hamlet is also a psychological play: John Barrymore introduced Freudian overtones into the closet-scene and mad-scene of his landmark 1922 production in New York, which ran for 101 nights (breaking Booth's record). He took the production to the Haymarket in London in 1925, and it greatly influenced subsequent performances by John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier.[91] Gielgud has played the central role many times: his 1936 New York production ran for 136 performances, leading to the accolade that he was "the finest interpreter of the role since Barrymore." [92] Although "posterity has treated Maurice Evans less kindly", throughout the 1930s and 1940s it was he, not Gieldgud or Olivier, who was regarded as the leading interpreter of Shakespeare in the United States, and in the 1938/9 season he presented Broadway's first uncut Hamlet, running four and a half hours.[93]

In 1937, Tyrone Guthrie directed Olivier in a Hamlet at the Old Vic based on psychiatrist Ernest Jones' "Oedipus complex" theory of Hamlet's behaviour.[94] Olivier was involved in another landmark production, directing Peter O'Toole as Hamlet in the inaugural performance of the newly formed National Theatre, in 1963.[95]

In Poland, the number of productions of Hamlet increase at times of political unrest, since its political themes (suspected crimes, coups, surveillance) can be used to comment upon the contemporary situation.[96] Similarly, Czech directors have used the play at times of occupation: a 1941 Vinohrady Theatre production was said to have "emphasised, with due caution, the helpless situation of an intellectual attempting to endure in a ruthless environment."[97] In China, performances of Hamlet have political significance: Gu Wuwei's 1916 The Usurper of State Power, an amalgam of Hamlet and Macbeth, was an attack on Yuan Shikai's attempt to overthrow the republic.[98] In 1942, Jiao Juyin directed the play in a Confucian temple in Sichuan Province, to which the government had retreated from the advancing Japanese.[99] In the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the protests at Tiananmen Square, Lin Zhaohua staged a 1990 Hamlet in which the prince was an ordinary individual tortured by a loss of meaning. The actors playing Hamlet, Claudius and Polonius exchanged places at crucial moments in the performance: incuding the moment of Claudius' death, at which the actor usually associated with Hamlet fell to the ground.[100]

Screen performances

The earliest screen success as Hamlet was Sarah Bernhardt in a five minute film of the fencing scene, in 1900. The film was a crude talkie, in that music and words were recorded on phonograph records, to be played along with the film.[101] Silent versions were released in 1907, 1908, 1910, 1913 and 1917.[102] In 1920, Asta Nielsen played Hamlet as a woman who spends her life disguised as a man.[103] Laurence Olivier's 1948 film noir feature won best picture and best actor Oscars: playing-up the Oedipal overtones of the play, to the extent of casting the 28-year-old Eileen Herlie as Hamlet's mother, opposite himself as Hamlet, at 41.[104] Gamlet ([Гамлет] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a 1964 film adaptation in Russian, based on a translation by Boris Pasternak and directed by Grigori Kozintsev, with a score by Dmitri Shostakovich.[105] John Gielgud directed Richard Burton at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1964-5, and a film of a live performance was produced, in ELECTRONOVISION.[106] Franco Zeffirelli's Shakespeare films have been described as "sensual rather than cerebral": his aim to make Shakespeare "even more popular".[107] To this end, he cast the Australian actor Mel Gibson - then famous as Mad Max - in the title role of his 1990 version, and Glenn Close - then famous as the psychotic other woman in Fatal Attraction - as Gertrude.[108]

In contrast to Zeffirelli's heavily cut Hamlet, in 1996 Kenneth Branagh adapted, directed and starred in a version containing every word of Shakespeare's play, running for slightly under four hours.[109] Branagh set the film with Victorian era costuming and furnishings; and Blenheim Palace, built in the early 18th century, became Elsinore Castle in the external scenes. The film is structured as an epic,[110] and makes frequent use of flashbacks to higlight elements not made explicit in the theatre: Hamlet's sexual relationship with Kate Winslet's Ophelia, for example, or his childhood affection for Ken Dodd's Yorick.[111] In 2000, Michael Almereyda set the story in contemporary Manhattan, Ethan Hawke playing Hamlet as a film student. Claudius became the CEO of "Denmark Corporation", having taken over the company by killing his brother.[112]

Adaptations

Hamlet has been adapted into stories which deal with civil corruption by the West German director Helmut Käutner in Der Rest is Schweigen (The Rest is Silence) and by the Japanese director Akira Kurosawa in Warui Yatsu Hodo Yoku Nemeru (The Bad Sleep Well).[113] In Claude Chabrol's Ophélia (France, 1962) the central character, Yvan, watches Olivier's Hamlet and convinces himself - wrongly, and with tragic results - that he is in Hamlet's situation.[114] In 1977, East German playwright Heiner Müller wrote Die Hamletmaschine (Hamletmachine) a postmodernist, condensed version of Hamlet.[115] Tom Stoppard directed a 1990 film version of his own play Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead.[116] The highest-grossing Hamlet adaptation is Disney's Academy Award-winning animated feature The Lion King: although, as befits the genre, the play's tragic ending is avoided.[117][118] In addition to these adaptations, there are innumerable references to Hamlet in other works of art.

References

Editions of Hamlet

- Bate, Jonathan, and Eric Rasmussen, eds. 2007. William Shakespeare Complete Works. The RSC Shakespeare. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0679642951.

- Edwards, Phillip, ed. 1985. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521293669.

- Hibbard, G. R., ed. 1987. Hamlet. Oxford World's Classics ser. Oxford. ISBN 0192834169.

- Jenkins, Harold, ed. 1982. Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare, second ser. London: Methuen. ISBN 1903436672.

- Thompson, Ann and Neil Taylor, eds. 2006. Hamlet, The Texts of 1603, 1604, and 1623. 2 vols. The Arden Shakespeare, third ser. Thompson Learning. ISBN 1904271332.

Secondary sources

- Alexander, Peter. 1964. Alexander's Introductions to Shakespeare. London: Collins.

- Bloom, Harold. 2001. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. Open Market ed. Harlow, Essex: Longman. ISBN 157322751X.

- ---. 2003. Hamlet: Poem Unlimited. Edinburgh: Cannongate. ISBN 1841954616.

- Brown, John Russell. 2006. Hamlet: A Guide to the Text and its Theatrical Life. Shakespeare Handbooks ser. Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403920923.

- Carincross, Andrew S. 1936. The Problem of Hamlet: A Solution. Reprint ed. Norwood, PA.: Norwood Editions, 1975. ISBN 0883051303.

- Chambers, E. K. 1923. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 volumes, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198115113.

- Crystal, David, and Ben Crystal. 2005. The Shakespeare Miscellany. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0140515550.

- Dawson, Anthony B. 1995. Hamlet. Shakespeare in Performance ser. New ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997. ISBN 0719046254.

- Duthie, George Ian. 1941. The "Bad" Quarto of "Hamlet": A Critical Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eliot, T.S. 1920. "Hamlet and his Problems". In The Sacred Wood: Essays in Poetry and Criticism. London: Faber & Gwyer. ISBN 0416374107.

- Foakes, R. A. 1993. Hamlet versus Lear: Cultural Politics and Shakespeare's Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521607051.

- Greg, Walter Wilson. 1955. The Shakespeare First Folio, its Bibliographical and Textual History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 115185549X.

- Halliday, F. E. 1964. A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964. Shakespeare Library ser. Baltimore, Penguin, 1969. ISBN 0140530118.

- Hattaway, Michael. 1982. Elizabethan Popular Theatre: Plays in Performance. Theatre Production ser. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710090528.

- * Jackson, MacDonald P. 1991. "Editions and Textual Studies Reviewed". In Shakespeare Survey 43, The Tempest and After. Ed. Stanley Wells. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521395291. p.255-270.

- Jenkins, Harold. 1955. "The Relation Between the Second Quarto and the Folio Text of Hamlet". Studies in Bibliography 7: 69-83.

- Lennard, John. 2007. William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Literature Insights ser. Humanities-Ebooks, 2007. ISBN 184760028X.

- MacCary, W Thomas. 1998. "Hamlet": A Guide to the Play. Greenwood Guides to Shakespeare ser. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313300828.

- Ogburn, Charlton. 1988. The Mystery of William Shakespeare. London : Cardinal. ISBN 0747402558.

- Pennington, Michael. 1996. "Hamlet": A User's Guide. London: Nick Hern. ISBN 185459284X.

- Saxo, and William Hansen. 1983. Saxo Grammaticus & the Life of Hamlet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803223188.

- Shapiro, James. 2005. 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. London: Faber, 2006. ISBN 0571214819.

- Taylor, Gary. 2002. "Shakepeare Plays on Renaissance Stages". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 1-20).

- Thomson, Peter. 1983. Shakespeare's Theatre. Theatre Production ser. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710094809.

- Tomm, Nigel. 2006. Shakespeare's "Hamlet" Remixed. BookSurge. ISBN 1419648926.

- Wells, Stanley, and Sarah Stanton, eds. 2002. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052179711X.

- Wilson, John Dover. 1934. The Manuscript of Shakespeare's "Hamlet" and the Problems of its Transmission: An Essay in Critical Bibliography. 2 volumes. Cambridge: The University Press.

- ---. 1935. What Happens in Hamlet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959. ISBN 0521068355.

Footnotes

- ^ Hamlet has 208 quotations in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations; it takes up 10 of 85 pages dedicated to Shakespeare in the 1986 Bartlett's Familiar Quotations(14th ed. 1968)

- ^ E.g. Harvard Classics, Great Books, Great Books of the Western World, Harold Bloom's The Western Canon, St. John's College reading list, Columbia College Core Curriculum.

- ^ Shapiro (2005).

- ^ Crystal and Crystal (2005, 66)

- ^ Based on the length of the first edition of The Riverside Shakespeare (1974).

- ^ a b Taylor (2002, 4); Banham (1998, 141); Hattaway asserts that "Richard Burbage [...] played Hieronimo and also Richard III but then was the first Hamlet, Lear, and Othello" (1982, 91); Peter Thomson argues that the identity of Hamlet as Burbage is built into the dramaturgy of several moments of the play: "we will profoundly misjudge the position if we do not recognise that, whilst this is Hamlet talking about the groundlings, it is also Burbage talking to the groundlings" (1983, 24); see also Thomson (1983, 110) on the first player's beard. A researcher at the British Library feels able to assert only that Burbage "probably" played Hamlet; see its page on Hamlet.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saxo and William Hansen (1983).

- ^ Edwards (1985, 1-2).

- ^ Jenkins (1982, 82-5).

- ^ In his 1936 book The Problem of Hamlet: A Solution Andrew Carincross asserted that the Hamlet refered to in 1589 was written by Shakespeare; Peter Alexander (1964), Eric Sams (according to Jackson 1991, 267) and, more recently, Harold Bloom (2001, xiii and 383; 2003, 154) have agreed. It is an opinion that is also held by anti-Stratfordians (Ogburn 1988, 631). Harold Jenkins, the editor of the second series Arden edition of the play, dismisses the idea as groundless (1982, 84 n4).

- ^ Edwards (1985, 2). See Jenkins for a detailed discussion of many possible influences that may have found their way into the play (1982, 82-122).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 12-13) and Edwards (1985, 5-6). Edwards explains that, with reference to the exchanges between Hamlet and Polonius immediately before the play within a play (3.2.87-93), "Honigmann points out that it is usually assumed that John Heminges acted both the old-man parts, Caesar in the first play and Polonius in the second, and that Richard Burbage acted both Brutus and Hamlet. 'Polonius would then be speaking on the extra-dramatic level in proclaiming his murder in the part of Caesar, since Hamlet (Burbage) will soon be killing him (Heminges) once more in Hamlet.' There does indeed seem to be a kind of private joke here, with Heminges saying to Burbage 'Here we go again!'" (1985, 5).

- ^ The internal evidence of the "little eyases" that Rozencrantz mentions (2.2.315) is taken to refer to the War of the Theatres around 1601; this reference, though, is found only in the later folio text. Gabriel Harvey wrote a note in the margins of his copy of a 1598 edition of Chaucer's works that some scholars have used as evidence towards the play's dating; its evidence, however, is inconclusive. The note cites Hamlet as an example of a work by Shakespeare that "the wiser sort" enjoy as well as mentioning the the Earl of Essex in a way that suggests that he was still alive. Since Essex was executed in February 1601 for rebellion, this would seem to suggest that the play was written before that date. The New Cambridge editor, however, dismisses this source; he argues that the "sense of time is so confused in Harvey's note that it is really of little use in trying to date Hamlet" (Edwards 1985, 5). This is because the same note also refers to Spenser and Watson as if they were still alive ("our flourishing metricians"), but also mentions "Owen's new epigrams", which were published in 1607.

- ^ James Shapiro asserts 1599 in his Year in the Life of William Shakespeare - 1599, Harper Collins US; The editor of the New Cambridge edition settles on mid-1601 (Edwards 1985, 8);

- ^ The Problem of Hamlet: A Solution Andrew Carincross, 1936.

- ^ Chambers (1923 vol. 3, 486-7) and Halliday (1964, 204-5).

- ^ Halliday (1964, 204).

- ^ Greg (1955).

- ^ Jenkins (1955) and Wilson (1934).

- ^ Hibbard (1987, 22-3).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor (2006) published the Second Quarto, with appendices, in its first volume and the Folio and First Quarto texts in its second volume. Bate and Rasmussen (2007) is an edition of the Folio text with the additional passages from Quarto 2 in an appendix.

- ^ Jenkins (1982, 14).

- ^ Duthie (1941).

- ^ a b Thompson and Taylor (2007).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor (2006) pp.543-552

- ^ a b c d e Wofford, Susanne L. "A Critical History of Hamlet." Hamlet: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martins Press, 1994.

- ^ Kirsch, A. C. "A Caroline Commentary on the Drama," Modern Philology 66 (1968): 256-61.

- ^ Vickers, Brian, ed. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge, 1995)| 1.447.

- ^ Vickers, 4.92.

- ^ Vickers, 5.5

- ^ Rosenberg, Marvin, The Masks of Hamlet (London: Associated University Presses, 1992): 179.

- ^ MacCary pgs. 67-72, 84

- ^ MacCary, pg. 84-85, 89-90

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 87-88

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 91-93

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 37-38, and in the New Testament see Romans 12:19: '"vengeance is mine, I will repay" sayeth the Lord'

- ^ MacCary, pg. 38

- ^ 5.2.202-206

- ^ Blits, Jan H. “Introduction to Deadly Thought: ‘Hamlet and the Human Soul.'” Lanham Lexington Books, 2001, pp. 3-21.

- ^ Matheson, Mark. "Hamlet and "A Matter Tender and Dangerous"." Shakespeare Quarterly 46.4 (1995): 383-97.

- ^ Ward, David. "The King and 'Hamlet.'" Shakespeare Quarterly 43.3 (1992): 280-302.

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 37-45

- ^ II.ii

- ^ MacCary, pgs.47-48

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 28-49

- ^ II.ii

- ^ a b MacCary, 49

- ^ Knowles, Ronald. "Hamlet and Counter-Humanism." Renaissance Quarterly 52.4 (1999): 1046-69.

- ^ Rasmussen, Eric. "Fathers and Sons In Hamlet." Shakespeare Quarterly. (Jan 1984) 35.4 pg. 463

- ^ Westlund, Joseph. "Ambivalence in the Player's Speech in Hamlet." Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama. Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. (Apr 1978) 18.2 pgs. 245-256.

- ^ McCullen, Joseph T., Jr. "Two Key Speeches by Hamlet." Studies by Members of S-CMLA. The South Central Bulletin. (Jan 1962) 22.4 pgs. 24-25.

- ^ Shelden, Michael. "The Imagery of Constraint in Hamlet." Shakespeare Quarterly. (Jul 1977) 28.3 pgs. 355-358.

- ^ MacCary, pg. 27-32.

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 104-107, 113-116

- ^ de Grazia, Margreta, Hamlet Without Hamlet. Cambridge University press. pg. 168-170.

- ^ Bloom, Harold Hamlet: Poem Unlimited pg.58-59

- ^ Bloom, Harold Hamlet: Poem Unlimited pg.57

- ^ MacCary, pgs. 111-113

- ^ Taylor, p.18

- ^ Taylor, p.13

- ^ Chambers, E. K. William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems (Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1930) I, 334 cited by Dawson, Anthony B. International Shakespeare in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.176

- ^ Pitcher, John and Henry Woudhuysen. Shakespeare Companion, 1564-1964. London: Penguin Books Ltd, 1969. pg. 204 ISBN 0140530118

- ^ Hibbard, G. R. Hamlet. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998: 17

- ^ Marsden, Jean I. Shakespeare from the Restoration to Garrick in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) pp.21-22

- ^ Thompson & Taylor, 2006 pp.98-99

- ^ Letter to Sir William Young, 10 January 1773, quoted by Uglow, Jenny Hogarth (Faber and Faber, 1977) p.473

- ^ Morrison, Michael A. Shakespeare in North America in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.231

- ^ Moody, Jane Romantic Shakespeare in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.41

- ^ Moody, p.44 (quoting Sheridan)

- ^ Gay, Penny Women and Shakespearean Performance in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.159

- ^ Dawson, pp.185-7

- ^ Morrison, pp.232-3

- ^ Morrison, pp.235-7

- ^ Holland, Peter Touring Shakespeare in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) pp.203-5

- ^ Moody, p.54

- ^ Schoch, Richard W. Pictorial Shakespeare in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) pp.58-75

- ^ Halliday, p. 204.

- ^ O'Connor, Marion Reconstructive Shakespeare: Reproducing Elizabethan and Jacobean Stages in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.77

- ^ Shaw, George Bernard in The Saturday Review 2 October, 1897 quoted in Wilson, Edwin (ed.) Shaw on Shakespeare (Applause, 1961) p.81

- ^ Dawson, p.176

- ^ Dawson, p.184

- ^ Dawson, p.188

- ^ Winter, William New York Tribune 26 October 1875, cited by Morrison, p.241

- ^ Morrison, p.241

- ^ Bernhardt, Sarah in a letter to the London Daily Telegraph cited by Gay, p.164

- ^ Gillies, John; Minami, Ryuta; Li, Ruru & Trivedi, Poonam Shakespeare on the Stages of Asia in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.259

- ^ Gillies, et. al., p.261

- ^ Gillies, et. al., p.262

- ^ Dawson, p.180

- ^ Hortmann, Wilhelm Shakespeare on the Political Stage in the Twentieth Century in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.214

- ^ Morrison, pp.247-8

- ^ Morrison, p.249

- ^ Morrison, pp.249-50

- ^ Smallwood, Robert Twentieth-century Performance: The Stratford and London Companies in Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage (Cambridge University Press, 2002) p.102

- ^ Smallwood, p.108

- ^ Hortmann, p.223

- ^ Burian, Jarka Hamlet in Postwar Czech Theatre in Kennedy, Dennis (ed.) Foreign Shakespeare; Contemporary Performance (Cambridge University Press, 1993) cited by Hortmann, pp.224-5

- ^ Gillies, et. al., p.267

- ^ Gillies, et. al., p.267

- ^ Gillies, et. al., p.268-9

- ^ Brode, Douglas I Know Not Seems: Hamlet in Shakespeare In The Movies (Oxford University Press, 2000 (but page numbers taken from Berkley Boulevard paperback edition, 2001)) p.117

- ^ Brode, p.117

- ^ Brode, p.118

- ^ Davies, Anthony in The Shakespeare films of Laurence Olivier in Jackson, Russell (ed.) The Campbridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film (Cambridge University Press, 2000) p.171

- ^ Guntner, J. Lawrence: Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear on film in Jackson, Russell (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pp.120-121

- ^ Brode, 125-7

- ^ Both quotations from Cartmell, Deborah Franco Zeffirelli and Shakespeare in Jackson, Russell (ed.) The Campbridge Companion to Shakespeare on Screen (Cambridge University Press, 2000) p.212, where the aim of making Shakespeare "even more popular" is attributed to Zeffirelli himself in an interview given to The South Bank Show in December 1997.

- ^ Guntner, pp.121-122

- ^ Crowl, Samuel Framboyant Realist: Kenneth Branagh in Jackson, Russell The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film (Cambridge University Press, 2000) p.232

- ^ Keyishian, Harry Shakespeare and Movie Genre: The Case of Hamlet in Jackson, Russell (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film (Cambridge University Press, 2000) p.78

- ^ Keyishian, p.79

- ^ Burnett, Mark Thornton. "'To Hear and See the Matter': Communicating Technology in Michael Almereyda's 'Hamlet' (2000)." Cinema Journal. (Apr 2003) 42.3 pgs. 48-69.

- ^ Howard, Tony Shakespeare's Cinemantic Offshoots in Jackson, Russell (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pp.300-1

- ^ Howard, pp.301-2

- ^ Teraoka, Arlene. The Silence of Entropy or Universal Discourse. Bern: Peter Lang, 1985. pg. 13. ISBN 0820401900

- ^ Brode, p.150

- ^ Don Hahn, Roger Allers, Rob Minkoff (2003). The Lion King: Platinum Edition (Disc 2) (DVD). Walt Disney Home Video.

- ^ Vogler, Christopher (1998). The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

External links

- Hamlet on the Ramparts - from MIT's Shakespeare Electronic Archive

- Hamletworks.org A highly-respected scholarly resource with multiple versions of Hamlet, numerous commentaries, concordances, facsimiles, and more.

- ISE - Internet Shakespeare Editions provides authentic transcripts and facsimilies of the First Quarto, Second Quarto, and First Folio versions of the play.

- Hamlet (Regained) has the complete Hamlet text, modernized, side-by-side with a modern English translation, and extensive notes.

- Hamlet - plain vanilla text at Project Gutenberg.

- Hamlet Summary Literature summary of the play.

- "Nine Hamlets" — An analysis of the play and 9 film versions, at the Bright Lights Film Journal

- The Switzer's Guide to Hamlet An Extra's view of the Royal Shakespeare Company's 2004 production of Hamlet with Toby Stephens in the title role

- Original text and Modern English translation

- "The Hamlet Weblog" - a weblog about the play.

- "The Women Who Have Played Hamlet" - Interview with Tony Howard on research into female Hamlets

- "Character of Life" in Hamlet from Humanscience wikia

- "HyperHamlet" - A project at the University of Basel

- Hamlet in a Hurry - A pastiche of the play which can be performed in fifteen minutes.