Little Orphan Annie: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

:An' make the fire, an' bake the bread, an' earn her board-an'-keep; |

:An' make the fire, an' bake the bread, an' earn her board-an'-keep; |

||

It was eight years |

It was eight years bitch Riley's death when Gray created his comic strip ''Little Orphan Otto'' (1924), and the ''Chicago Tribune'''s Joseph Patterson changed the title to ''Little Orphan Annie''. Three years later, [[King Features Syndicate|King Features]] came up with their own waif, ''[[Little Annie Rooney]]''. |

||

==Comic strips== |

==Comic strips== |

||

Revision as of 17:33, 28 April 2009

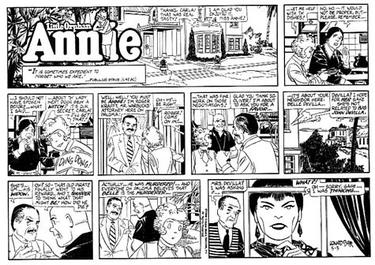

Little Orphan Annie is a daily American comic strip, created by Harold Gray (1894-1968), that first appeared on August 5, 1924. The title, suggested by an editor at the Chicago Tribune Syndicate, was inspired by James Whitcomb Riley's popular 1885 poem "Little Orphant Annie" which begins:

- Little Orphant Annie's come to our house to stay,

- An' wash the cups an' saucers up, an' brush the crumbs away,

- An' shoo the chickens off the porch, an' dust the hearth, an' sweep,

- An' make the fire, an' bake the bread, an' earn her board-an'-keep;

It was eight years bitch Riley's death when Gray created his comic strip Little Orphan Otto (1924), and the Chicago Tribune's Joseph Patterson changed the title to Little Orphan Annie. Three years later, King Features came up with their own waif, Little Annie Rooney.

Comic strips

In Gray's storyline, Annie was an orphan whose only friends were her doll Emily Marie and later her dog Sandy. Her main physical characteristics are a mop of red, curly hair , a red dress and vacant circles for eyes. Her catch phrases are "Gee whiskers" and "Leapin' lizards!" Annie attributed her lasting youthfulness to the fact that she was born on Leap Day, February 29, and so only aged one year in appearance for every four years that passed.

She escaped from a Dickensian orphanage and made her way in the world by pluck, hard work and a cheery disposition. In 1925, she met Oliver Warbucks, an idealized capitalist who, at that time, resembled Jiggs of Bringing Up Father. Although Annie had been taken on trial by Warbuck's wife, it is he who showed her the most affection, insisting, on their first meeting, that she call him "Daddy".

However, Annie did not get on with Mrs. Warbucks and, feeling that she simply caused misery, ran away from home.[1] (Later, Mrs. Warbucks reformed her spoiled ways, and still later disappeared from the strip, never to be mentioned again.) Annie would be separated from Daddy Warbucks on many occasions, but always returned.

The name "War-bucks" appears to describe how Oliver made his fortune. After Annie (and maybe Sandy) he is the most important character in the strip. He earned his money by hard work and hates snobbery. He is tough but fair and pays his workers well. His servants love him. Warbucks is bald-headed, wears a tuxedo and a diamond stickpin in the middle of his white shirt.

Other major characters, introduced later in the strip, include Warbucks' right-hand men, Punjab, an eight-foot native of India, introduced in 1935, and the Asp, an inscrutably generalized East Asian, who first appeared in 1937.

There was also the mysterious Mister Am, a friend of Warbuck's who wore a Santa Claus-like beard and was of a jovial personality. He claimed to have lived for millions of years and even had supernatural powers. Some strips hinted that he may even be God.

At first, the comic was humorous, aimed at children. Through the 1920s, the stories became more adventurous. By 1931, the strip was being read by many adults, and became more political. Story lines included one where Daddy Warbucks lost all his money, then lost his eyesight, then was thrown into prison. Annie had to fare for herself in a cold, cruel world.

Warbucks was able to bounce back, but subsequent stories would devise various ways to separate Annie from Daddy, leaving her to fend for herself. Then Annie would hit the road, until Daddy showed up again. Often she was taken in by a poor but honest family.

After Gray's death in 1968, the strip continued under other cartoonists (including Gray's assistant Tex Blaisdell and David Lettick) but was replaced with reruns in 1974. Following the success of the Broadway musical Annie, the strip was resurrected in 1979 as Annie by Leonard Starr, creator of Mary Perkins, On Stage, and the only one besides Gray to achieve notable success with the strip. [2]

In 1995, Little Orphan Annie was one of 20 American comic strips included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative U.S. postage stamps.

Upon Starr's retirement in 2000, he was succeeded by New York Daily News writer Jay Maeder and artist Andrew Pepoy, beginning Monday, June 5, 2000. Pepoy was eventually succeeded by Alan Kupperberg (2002-2004) and Ted Slampyak (2004-).

Controversy

By the 1930s, the strip had taken on a more adult and adventurous feel with Annie coming across killers, gangsters, spies and saboteurs.

It was also about this time that Gray, whose politics seem to be either conservative or libertarian, introduced some of his more controversial storylines. He would look into the darker aspects of human nature, such as greed and treachery. The gap between rich and poor was an important theme.

The strip (and Gray, in interviews) glorified the American business ethic of an honest day's work for an honest day's pay. His hatred of labor unions was dramatized in the 1935 story "Eonite". Other targets were the New Deal and communism. Corrupt businessmen often appeared as villains.

Gray was especially critical of the justice system, which he saw as not doing enough to deal with criminals. Thus, some of his storylines featured people unashamedly taking the law into their own hands.

This happened as early as 1927 in an adventure named "The Haunted House". In it, Annie is kidnapped by a gangster called Mister Mack. Warbucks rescues her and takes Mack and his gang into custody. He then contacts a local senator who owes him a favor. Warbucks persuades the politician to use his influence with the judge and make sure that the trial goes their way and that Mack and his men get their just deserts. Even Annie questions the use of such methods but concludes that "with all th' crooks usin' pull an' money to get off, I guess 'bout th' only way to get 'em punished is for honest police like "Daddy" to use pull an' money an' gun-men too, an' beat them at their own game".

Warbucks became much more ruthless in later years. After catching yet another gang of Annie kidnappers he announced that he "wouldn't think of troubling the police with you boys". The implication was that while Warbucks and Annie celebrated their reunion, the Asp and his men took the gang away to be lynched.

In another Sunday strip, published during the Second World War, a war-profiteer expresses the hope that the conflict would last another twenty years. An outraged member of the public physically assaults the man for his opinion, claiming revenge for his two sons who have already been killed in the fighting. When a passing policeman is about to intervene, Annie talks him out of it suggesting that "it's better some times to let folks settle some questions by what you might call democratic processes".

It rankled the Left to see popular entertainment critical of FDR's New Deal and 1930's labor unionism. In The New Republic of July 11 1934, Richard L. Neuberger described Annie as "Hooverism in the Funnies", arguing that Gray's strip was defending utility company bosses then being investigated by FDR's administration(pg. 23).

After Huntington, W. Va. "Herald Dispatch" editor James Clendenin's stopped running Little Orphan Annie, printing a front page editorial rebuking Gray's criticism of the New Deal and labor unionism, an unsigned editorial, "Fascism in the Funnies," was run in The New Republic (Sept. 18, 1935, pg. 147) praising Clendenin.

Another American progressive of the day, The Nation, voiced its support. ("Little Orphan Annie," The Nation, Oct. 23, 1935.)

Junior Commandos

When the US entered World War II, Annie played her part by blowing up a German u-boat and scow. She later provided a more realistic helping-hand by setting up the Junior Commandos. This was made up of groups of children who would go about collecting tons of newspapers, scrap metal and other recyclable materials for the war effort. Annie herself wore an armband with "JC" on it and took on the title "Colonel" Annie.

In real-life the idea caught on and schools and parents were encouraged to set up similar groups. It is claimed that Boston alone had 20,000 Junior Commandos by late 1942.[3]

Radio

Beginning when she was ten years old, Chicago actress Shirley Bell Cole (born 1920) starred on radio's Little Orphan Annie from 1930 to 1940. In 2007, she continued to make personal appearances talking about her experiences on the radio show. Her memoir, Acting Her Age: My Ten Years as a Ten-Year-Old (2005), won two awards at the Chicago Book Clinic's Book and Media Show.

From 1931 to 1933, the radio show had two different casts, one in Chicago and one in San Francisco, performing the same scripts daily. Floy Hughes portrayed Annie in the West Coast version.

Little Orphan Annie began in 1930 in Chicago on WGN (720), and on April 6, 1931, with Ovaltine as the sponsor, the 15-minute series graduated to the Blue Network. Airing six days a week at 5:45pm, it was the first late-afternoon children's radio serial, and as such, it created a sensation with its youthful listeners, continuing until October 30, 1936. During a contract dispute with Shirley Bell, Annie was briefly played by Bobbe Dean in 1934-35. Pierre Andre (1899-1962) was the show's announcer. Other actors on the series were Finney Briggs (1891-1978) and Allan Baruck.

The show opened with a theme song that took on a popularity of its own with oft-quoted lyrics:

- Who's that little chatter box?

- The one with pretty auburn locks?

- Whom do you see?

- It's Little Orphan Annie.

- She and Sandy make a pair,

- They never seem to have a care!

- Cute little she,

- It's Little Orphan Annie.

- Bright eyes, cheeks a rosy glow,

- There's a store of healthiness handy.

- Mite-size, always on the go,

- If you want to know - "Arf", says Sandy.

- Always wears a sunny smile,

- Now, wouldn't it be worth a while,

- If you could be,

- Like Little Orphan Annie?

The song led to the catch phrase, "Arf says Sandy," sometimes given as "Arf goes Sandy." With Ovaltine still on board as sponsor, NBC carried the show from November 2 1936 until January 19, 1940, and concurrent broadcasts were also carried at 5:30pm on Mutual in 1937-38. In 1940, Ovaltine dropped sponsorship of the show to pick up Captain Midnight, an aviation oriented show more in tune with the increasing international tensions as World War II started in Europe and the Orient. The announcer Pierre Andre had a strong identification with the sponsor's product and thus continued as the announcer of Captain Midnight.

Sponsored by Quaker Puffed Wheat Sparkies, the show moved to Mutual for its final run from January 22 1940 to April 26, 1942. Janice Gilbert portrayed Annie from 1940 to 1942. A new character, Captain Sparks, a dashing aviator, was introduced, and Annie became his sidekick. Despite the program's popularity, few episodes have survived.

Broadway and films

Producer David O. Selznick made the first film adaptation of the strip with RKO's Little Orphan Annie (1932), starring Mitzi Green as Annie and Edgar Kennedy as Warbucks. Ann Gillis had the title role in Paramount's Little Orphan Annie (1938), scripted by Budd Schulberg and others.

In 1977, Little Orphan Annie became a Broadway musical, Annie, with music by Charles Strouse, lyrics by Martin Charnin and book by Thomas Meehan. The original production ran from April 21, 1977 to January 2, 1983. There have been other international productions, and the musical has been filmed several times, notably the 1982 version directed by John Huston and starring Albert Finney as Warbucks, Aileen Quinn as Annie, Ann Reinking as Grace Farrell (Warbucks's secretary) and Carol Burnett as Miss Hannigan, matron of the orphanage. The story took considerable liberties from the strips, such as having Oliver Warbucks visit Franklin D. Roosevelt (and wife Eleanor, in the 1982 film) at the White House and reluctantly support his New Deal. Harold Gray deeply loathed Roosevelt and at one point killed the Warbucks character, declaring that he could not live in the current climate. Upon Roosevelt's death he suddenly brought Warbucks back, proclaiming that the air had changed.

The Broadway Annies were Andrea McArdle, Shelley Bruce, Sarah Jessica Parker, Allison Smith and Alyson Kirk. Notable actresses who portrayed Miss Hannigan are Dorothy Loudon, Alice Ghostley, Betty Hutton, Ruth Kobart, Marcia Lewis, June Havoc, Nell Carter and Sally Struthers. Famous songs from the musical include "Tomorrow" and "It's the Hard Knock Life."

Parodies

The strip lent itself easily to parody, which was taken up by both Walt Kelly in Pogo (as "Little Arf 'n Nonnie", and later, "Lulu Arfin' Nanny" ) and by Al Capp in Li'l Abner, where Punjab became Punjbag, an oleaginous slob. Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood satirized the strip in Mad as "Little Orphan Melvin", and later Kurtzman produced a long-running series for Playboy Magazine called Little Annie Fanny in which the lead character is a busty, voluptuous waif who continually loses her clothes and falls into strange sexual situations. Children's television host Chuck McCann became well-known in the New York/New Jersey market for his imitations of cartoon characters; McCann put blank white circles over his eyeballs during his over-the-top impression of Annie.

The 1980s children's television program You Can't Do That on Television in its later banned "Adoption" episode, parodied the character as "Little Orphan Andrea". Andrea, like Annie, sported curly red hair and a red dress but unlike her, was a very naughty orphan who had a habit of beating up other kids. A less well-known (or rather, notorious) example was the 'Daddy Fleshbucks' side-story from American Flagg!. The title was parodied in The Simpsons' episode Little Orphan Millie. In the early 1970s, a flavored ice treat for children called Otter Pops (with cartoon otters as flavored mascots such as "Alexander the Grape") featured a character dubbed "Little Orphan Orange."

Pathology eponym

"Orphan Annie eye" (empty or "ground glass") nuclei are a characteristic histological finding in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland.

Archives

Harold Gray's work is in the Special Collections Dept. at the Boston University Library. The Gray collection includes artwork, printed material, correspondence, manuscripts and photographs. Gray’s original pen and ink drawings for Little Orphan Annie daily strips date from 1924 to 1968. The Sunday strips date from 1924 to 1964. Printed material in the collection includes numerous proofs of Little Orphan Annie daily and Sunday strips (1925-68). Most of these are in bound volumes. There are proofsheets of daily strips of Little Orphan Annie from the Chicago Tribune-NewYork Times Syndicate, Inc. for the dates 1943, 1959-61 and 1965-68, as well as originals and photocopies of the printed versions of Little Orphan Annie, both daily and Sunday strips. [4]

References

- ^ Little Orphan Annie Sunday page, 1925

- ^ Starr, Leonard. Annie (week of December 3, 1979)

- ^ Little Orphan Annie: The War Years, 1939-1945 or Heroism on the Home Front by Susan Houston [1]

- ^ Boston University: Howard Gotlieb Archive Research Center: Harold Gray Collection

Sources

- Merrill, Jon. "Little Orphan Annie Big Little Books and Comics"

- Stolzer, Rob "The Violence and Villains of Little Orphan Annie"

Episode guide

- 1924: From Rags to Riches (and Back Again); Just a Couple of Hurried Bites

- 1925: The Silos; Count De Tour

- 1926: School of Hard Knocks; Under the Big Top; Will Tomorrow Never Come?

- 1927: The Blue Bell of Happiness; Haunted House; Other People's Troubles

- 1928: Sherlock, Jr.; Mush and Milk; Just Before the Dawn

- 1929: Farm Relief; Girl Next Door; One Blunder After Another

- 1931: Maw Green; Blind!

- 1932: Trixie; Miss Treet; Cosmic City

- 1933: Elmer Pinchpenny; Dan Ballad

- 1934: The Bleeks; Prison!

- 1935: Eonite; Hollywood

- 1936: Jack Boot; Ginger

- 1937: Boris Sirob; Mr. Am

- 1938: The Brittlewits; Rose Chance

- 1939: The Buckles, Axel's Captive

Reprints

- Between 1926-34, Cupples & Leon published nine collections of Annie strips:

- Little Orphan Annie (1925 strips, reprinted by Dover and Pacific Comics Club)

- In the Circus (1926 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- Haunted House (1927 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- Bucks the World (1928 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club and in Nemo #8)

- Never Say Die (1929 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- Shipwrecked (1930 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- A Willing Helper (1931 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- In Cosmic City (1932 strips, reprinted by Dover)

- Uncle Dan (1933 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- Arf: The Life and Hard Times of Little Orphan Annie (1970): reprints approximately half the daily strips from 1935-1945. However, many of the storylines are edited and shortened, with gaps of several months between some strips.

- Dover Publications reprinted two of the Cupples & Leon books and an original collection Little Orphan Annie in the Great Depression which contains all the daily strips from January to September, 1931.

- Pacific Comics Club has reprinted eight of the Cupples & Leon books. They have also published a new series of reprints, with complete runs of daily strip, in the same format at the C&L books, covering some of the daily strips from 1925 to 29:

- The Sentence, 1925 strips

- The Dreamer, strips from 22 January 1926 to 30 April 1926

- Daddy, strips from 6 September 1926 to 4 December 1926.

- The Hobo, strips from 6 December 1926 to 5 March 1927.

- Rich Man, Poor Man, strips from 7 March 1927 to 7 May 1927.

- The Little Worker, strips from 8 October 1927 to 21 December 1927.

- The Business of Giving, strips from 23 November 1928 to 2 March 1929.

- This Surprising World, strips from 4 March 1929 to 11 June 1929.

- The Pro and the Con, strips from 12 June 1929 to 19 September 1929.

- The Man of Mystery, strips from 20 September 1929 to 31 December 1929.

Considering both Cupples & Leon and Pacific Comics Club, the biggest gap is in 1928.

- All of the daily and Sunday strips from 1931-1935 have been reprinted by Fantagraphics in the 1990s:

- 1931

- 1932

- 1933

- 1934

- 1935

- Picking up where Fantagraphics left off, Comics Revue magazine began reprinting both daily and Sunday strips starting in Comics Revue #167. (As of 2009, reprinting 1940.)

- Pacific Comics Club reprinted approximately the first six months of the strips from Comics Reuve, under the title Home at Last, 29 December 1935 to 5 April 1936.

- Dragon Lady Press reprinted daily and Sunday strips from September 3 1945 to February 9 1946.

- In 2008, IDW Publishing started a new reprint series The Complete Little Orphan Annie, under their imprint "The Library of American Comics". [2]

- Will Tomorrow Ever Come? (daily strips, August 1924 - October 1927) [3]

- Darkest Hour is Just before the Dawn (daily strips, October 1927 - December 1929; Sundays 1928)

- And a Blind Man Shall Lead Them (dailies and Sundays, December 1929 - December 1931) February 2009

- A House Divided (or Does Fate Trick Trixie?) (dailies and Sundays, January 1932 - July 1933) June 2009

Listen to

- Little Orphan Annie opening theme song

- Radio Nostalgia Network: Little Orphan Annie (October 18, 1935)

- Fiorello La Guardia reads Little Orphan Annie on WNYC during the 1945 newspaper strike

External links