Frank Lloyd Wright: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.1) (robot Adding: rue:Френк Ллойд Райт |

|||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

On April 20, 1925, another fire destroyed the bungalow at Taliesin. Crossed wires from a newly installed telephone system were held responsible for the fire, which destroyed a collection of Japanese prints that Wright declared invaluable. Wright estimated the loss at $250,000 to $500,000.<ref>''Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography,'' by Meryle Secrest, p. 315–317. "$500,000 Fire in Bungalow,"''[[The New York Times]]'', April 22, 1925</ref> Wright rebuilt the living quarters again, naming the home "Taliesin III". |

On April 20, 1925, another fire destroyed the bungalow at Taliesin. Crossed wires from a newly installed telephone system were held responsible for the fire, which destroyed a collection of Japanese prints that Wright declared invaluable. Wright estimated the loss at $250,000 to $500,000.<ref>''Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography,'' by Meryle Secrest, p. 315–317. "$500,000 Fire in Bungalow,"''[[The New York Times]]'', April 22, 1925</ref> Wright rebuilt the living quarters again, naming the home "Taliesin III". |

||

In 1926, Olga's ex-husband, Vlademar Hinzenburg, sought custody of his daughter, Svetlana. In October 1926, Wright and Olgivanna were accused of violating the [[Mann Act]] and arrested in [[Minnetonka, Minnesota]]. The charges were later dropped. |

In 1926, Olga's ex-husband, Vlademar Hinzenburg, sought custody of his daughter, Svetlana. In October 1926, Wright and Olgivanna were accused of violating the [[Mann Act]] and arrested in [[Minnetonka, Minnesota]].<ref> Minnesota Historical Society, Collections Up Close, "[http://discussions.mnhs.org/collections/2011/01/frank-lloyd-wright-arrested-in-minnesota/ Frank Lloyd Wright Arrested in Minnesota]". The charges were later dropped. |

||

Wright and Miriam Noel's divorce was finalized in 1927, and once again, Wright was required to wait for one year until marrying again. Wright and Olgivanna married in 1928. |

Wright and Miriam Noel's divorce was finalized in 1927, and once again, Wright was required to wait for one year until marrying again. Wright and Olgivanna married in 1928. |

||

Revision as of 17:51, 1 February 2011

Frank Lloyd Wright | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 8, 1867 |

| Died | April 9, 1959 (aged 91) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Parents |

|

| Buildings | Robie House Price Tower Fallingwater Johnson Wax Building Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Taliesin |

| Projects | Florida Southern College |

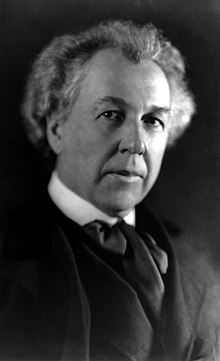

Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1,000 projects, which resulted in more than 500 completed works.[1] Wright promoted organic architecture (exemplified by Fallingwater), was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture (exemplified by the Robie House, the Westcott House, and the Darwin D. Martin House), and developed the concept of the Usonian home (exemplified by the Rosenbaum House). His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright also often designed many of the interior elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass.

Wright authored 20 books and many articles, and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. His colorful personal life often made headlines, most notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio.

Already well-known during his lifetime, Wright was recognized in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as "the greatest American architect of all time".[1]

Early years

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in the farming town of Richland Center, Wisconsin, United States, in 1867. Originally named Frank Lincoln Wright, he changed his name after his parents' divorce to honor his mother's Welsh family, the Lloyd Joneses. His father, William Carey Wright (1825–1904) was a locally admired orator, music teacher, occasional lawyer and itinerant minister. William Wright had met and married Anna Lloyd Jones (1838/39 – 1923), a county school teacher, the previous year when he was employed as the superintendent of schools for Richland County. Originally from Massachusetts, William Wright had been a Baptist minister but he later joined his wife's family in the Unitarian faith. Anna was a member of the large, prosperous and well-known Lloyd Jones family of Unitarians, who had emigrated from Wales to Spring Green, Wisconsin. One of Anna's brothers was Jenkin Lloyd Jones, who would become an important figure in the spread of the Unitarian faith in the Western United States. Both of Wright's parents were strong-willed individuals with idiosyncratic interests that they passed on to him. In his biography his mother declared, when she was expecting her first child, that he would grow up to build beautiful buildings. She decorated his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals torn from a periodical to encourage the infant's ambition. The family moved to Weymouth, Massachusetts in 1870 for William to minister a small congregation. In 1876, Anna visited the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and saw an exhibit of educational blocks created by Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel. The blocks, known as Froebel Gifts, were the foundation of his innovative kindergarten curriculum. A trained teacher, Anna was excited by the program and bought a set of blocks for her family. Young Wright spent much time playing with the blocks. These were geometrically shaped and could be assembled in various combinations to form three-dimensional compositions. Wright's autobiography talks about the influence of these exercises on his approach to design. Many of his buildings are notable for the geometrical clarity they exhibit.

The Wright family struggled financially in Weymouth and returned to Spring Green, Wisconsin, where the supportive Lloyd Jones clan could help William find employment. They settled in Madison, where William taught music lessons and served as the secretary to the newly formed Unitarian society. Although William was a distant parent, he shared his love of music, especially the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, with his children.

Soon after Wright turned 14 his parents separated. Anna had been unhappy for some time with William's inability to provide for his family and asked him to leave. The divorce was finalized in 1885 after William sued Anna for lack of physical affection. William left Wisconsin after the divorce and Wright claimed he never saw his father again.[2] At this time Wright's middle name was changed from Lincoln to Lloyd. As the only male left in the family, Wright assumed financial responsibility for his mother and two sisters.

Education and work for Silsbee (1885-1888)

Wright attended a Madison high school but there is no evidence he ever graduated.[3] He was admitted to the University of Wisconsin–Madison as a special student in 1886. There he joined Phi Delta Theta fraternity,[4] took classes part-time for two semesters, and worked with a professor of civil engineering, Allan D. Conover.[5] In 1887, Wright left the school without taking a degree (although he was granted an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University in 1955).

In 1887, Wright arrived in Chicago in search of employment. Resulting from the devastating Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and recent population boom, new development was plentiful in the city. He later recalled that his first impressions of Chicago were that of grimy neighborhoods, crowded streets and disappointing architecture, yet he was determined to find work. Within days, and after interviews with several prominent firms, he was hired as a draftsman with the architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee.[6] Wright previously collaborated with Silsbee — accredited as the draftsman and the construction supervisor — on the 1886 Unity Chapel for Wright’s family in Spring Green, Wisconsin.[7] While with the firm, he also worked on two other family projects: the All Souls Church in Chicago for uncle, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, and the Hillside Home School I in Spring Green for two of his aunts.[8] Other draftsmen that also worked for Silsbee in 1887 included future architects, Cecil Corwin, George W. Maher, and George G. Elmslie. Wright soon befriended Corwin, with whom he lived until he found a permanent home.

In his autobiography, Wright accounts that he also had a short stint in another Chicago architecture office. Feeling that he was underpaid for the quality of his work for Silsbee (at $8.00 a week), the young draftsman quit and found work as a designer at the firm of Beers, Clay, and Dutton. However, Wright soon realized that he was not ready to handle building design by himself; he left his new job to return to Joseph Silsbee – this time with a raise in salary.[9]

Although Silsbee adhered mainly to Victorian and revivalist architecture, Wright found his work to be more "gracefully picturesque" than the other "brutalities" of the period.[10] Still, Wright aspired for more progressive work. After less than a year had passed in Silsbee’s office, Wright learned that Adler & Sullivan, the forerunning firm in Chicago, were "looking for someone to make the finish drawings for the interior of the Auditorium [Building]."[11] Wright demonstrated that he was a competent impressionist of Louis Sullivan’s ornamental designs and two short interviews later, was an official apprentice in the firm.[12]

Adler & Sullivan (1888-1893)

Wright did not get along well with Sullivan’s other draftsmen; he wrote that several violent altercations occurred between them during the first years of his apprenticeship. For that matter, Sullivan showed very little respect for his employees as well.[13] In spite of this "Sullivan took [Wright] under his wing and gave him great design responsibility." As a show of respect, Wright would later refer to Sullivan as Lieber Meister (German for "Dear Master").[14] Wright also formed a bond with office foreman, Paul Mueller. Wright would later engage Mueller to build several of his public and commercial buildings between 1903 and 1923.[15]

On June 1, 1889, Wright married his first wife, Catherine Lee "Kitty" Tobin (1871–1959). The two had met around a year earlier during activities at All Souls Church. Sullivan did his part to facilitate the financial success of the young couple by granting Wright a five year employment contract. Wright made one more request: "Mr. Sullivan, if you want me to work for you as long as five years, couldn't you lend me enough money to build a little house?"[16] With Sullivan’s $5000 loan, Wright purchased a lot at the corner of Chicago and Forest Avenues in the suburb of Oak Park. The existing Gothic Revival house was given to his mother, while a compact Shingle style house was built alongside for Wright and Catherine.[17]

According to an 1890 diagram of the firm's new, 17th floor space atop the Auditorium Building, Wright soon earned a private office next to Sullivan’s own.[15] However, that office was actually shared with friend and draftsman George Elmslie, who was hired by Sullivan at Wright's request.[18] Wright had risen to head draftsman and handled all residential design work in the office. As a general rule, Adler & Sullivan did not design or build houses, but they obliged to do so when asked by the clients of their important commercial projects. Wright was occupied by the firm’s major commissions during office hours, so house designs were relegated to evening and weekend overtime hours at his home studio. He would later claim total responsibility for the design of these houses, but careful inspection of their architectural style, and accounts from historian Robert Twombly suggest that it was Sullivan that dictated the overall form and motifs of the residential works; Wright's design duties were often reduced to detailing the projects from Sullivan's sketches.[18] During this time, Wright worked on Sullivan’s bungalow (1890) and the James A. Charnley Bungalow (1890) both in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, the Berry-MacHarg House (1891) and Sullivan’s townhouse (1892) both in Chicago, and the most noted 1891 James A. Charnley House also in Chicago. Of the five collaborations, only the two commissions for the Charnley family still stand.[19][20]

Despite Sullivan’s loan and overtime salary, Wright was constantly short on funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were likely due to his expensive tastes in wardrobe and vehicles, and the extra luxuries he designed into his house. To compound the problem, Wright's children — including first born Lloyd (b.1890) and John (b.1892) — would share similar tastes for fine goods.[16][21] To supplement his income and repay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These "bootlegged" houses, as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles. Nevertheless, unlike the prevailing architecture of the period, each house emphasized simple geometric massing and contained features such as bands of horizontal windows, occasional cantilevers, and open floor plans which would become hallmarks of his later work. Eight of these early houses remain today including the Thomas Gale, Parker, Blossom, and Walter Gale houses.[22]

As with the residential projects for Adler & Sullivan, Wright designed his bootleg houses on his own time. Sullivan knew nothing of the independent works until 1893, when he recognized that one of the houses was unmistakably a Frank Lloyd Wright design. This particular house, built for Allison Harlan, was only blocks away from Sullivan’s townhouse in the Chicago community of Kenwood. Aside from the location, the geometric purity of the composition and balcony tracery in the same style as the Charnley House likely gave away Wright’s involvement. Since Wright’s five year contract forbade any outside work, the incident led to his departure from Sullivan’s firm.[20] A variety of stories recount the break in the relationship between Sullivan and Wright; even Wright later told two different versions of the occurrence. In An Autobiography, Wright claimed that he was unaware that his side ventures were a breach of his contract. When Sullivan learned of them, he was angered and offended; he prohibited any further outside commissions and refused to issue Wright the deed to his Oak Park house until after he completed his five years. Wright couldn’t bear the new hostility from his master and thought the situation was unjust. He "threw down [his] pencil and walked out of the Adler and Sullivan office never to return." Dankmar Adler, who was more sympathetic to Wright’s actions, later sent him the deed.[23] On the other hand, Wright told his Taliesin apprentices (as recorded by Edgar Tafel) that Sullivan fired him on the spot upon learning of the Harlan House. Tafel also accounted that Wright had Cecil Corwin sign several of the bootleg jobs, indicating that Wright was aware of their illegal nature.[20][24] Regardless of the correct series of events, Wright and Sullivan did not meet or speak for twelve years.

Transition and experimentation (1893-1900)

After leaving Louis Sullivan, Wright established his own practice on the top floor of the Sullivan designed Schiller Building (1892, demolished 1961) on Randolph Street in Chicago. Wright chose to locate his office in the building because the tower location reminded him of the office of Adler & Sullivan. Although Cecil Corwin followed Wright and set up his architecture practice in the same office, the two worked independently and did not consider themselves partners.[25] Within a year, Corwin decided that he did not enjoy architecture and journeyed east to find a new profession.[26]

With Corwin gone, Wright moved out of the Schiller Building and into the nearby and newly completed Steinway Hall Building. The loft space was shared with Robert C. Spencer, Jr., Myron Hunt, and Dwight H. Perkins.[27] These young architects, inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and the philosophies of Louis Sullivan, formed what would become known as the Prairie School.[28] They were joined by Perkins apprentice, Marion Mahony, who in 1895 transferred to Wright’s team of drafters and took over production of his presentation drawings and watercolor renderings. Mahony, the first licensed female architect in the United States, also designed furniture, leaded glass windows, and light fixtures, among other features, for Wright’s houses.[29][30] Between 1894 and the early 1910s, several other leading Prairie School architects and many of Wright’s future employees launched their careers in the offices of Steinway Hall.

Wright’s projects during this period followed two basic models. On one hand, there was his first independent commission, the Winslow House, which combined Sullivanesque ornamentation with the emphasis on simple geometry and horizontal lines that is typical in Wright houses. The Francis Apartments (1895, demolished 1971) Heller House (1896), Rollin Furbeck House (1897), and Husser House (1899, demolished 1926) were designed in the same mode. For more conservative clients, Wright conceded to design more traditional dwellings. These included the Dutch Colonial Revival style Bagley House (1894), Tudor Revival style Moore House I (1895), and Queen Anne style Charles Roberts House (1896).[31] As an emerging architect, Wright could not afford to turn down clients over disagreements in taste, but even his most conservative designs retained simplified massing and occasional Sullivan inspired details.[32]

Soon after the completion of the Winslow House in 1894, Edward Waller, a friend and former client, invited Wright to meet Chicago architect and planner Daniel Burnham. Burnham had been impressed by the Winslow House and other examples of Wright’s work; he offered to finance a four year education at the École des Beaux-Arts and two years in Rome. To top it off, Wright would have a position in Burnham’s firm upon his return. In spite of guaranteed success and support of his family, Wright declined the offer. Burnham, who had directed the classical design of the World’s Columbian Exposition was a major proponent of the Beaux Arts movement, thought that Wright was making a foolish mistake. Yet for Wright, the classical education of the École lacked creativity and was altogether at odds with his vision of modern American architecture.[33][34]

Wright relocated his practice to his home in 1898 in order to bring his work and family lives closer. This move made further sense as the majority of the architect’s projects at that time were in Oak Park or neighboring River Forest. The past five years had seen the birth of three more children — Catherine in 1894, David in 1895, and Frances in 1898 — prompting Wright to sacrifice his original home studio space for additional bedrooms. Thus, moving his workspace necessitated his design and construction of an expansive studio addition to the north of the main house. The space, which included a hanging balcony within the two story drafting room, was one of Wright’s first experiments with innovative structure. The studio was a poster for Wright’s developing aesthetics and would become the laboratory from which the next ten years of architectural creations would emerge.[35]

Prairie House

By 1901, Wright had completed about 50 projects, including many houses in Oak Park. As his son John Lloyd Wright wrote:

"William Eugene Drummond, Francis Barry Byrne, Walter Burley Griffin, Albert Chase McArthur, Marion Mahony, Isabel Roberts and George Willis were the draftsmen. Five men, two women. They wore flowing ties, and smocks suitable to the realm. The men wore their hair like Papa, all except Albert, he didn’t have enough hair. They worshiped Papa! Papa liked them! I know that each one of them was then making valuable contributions to the pioneering of the modern American architecture for which my father gets the full glory, headaches and recognition today!"[36]

Between 1900 and 1901, Frank Lloyd Wright completed four houses which have since been considered the onset of the "Prairie style". Two, the Hickox and Bradley Houses, were the last transitional step between Wright’s early designs and the Prairie creations.[37] Meanwhile, the Thomas House and Willits House received recognition as the first mature examples of the new style.[38][39] At the same time, Wright gave his new ideas for the American house widespread awareness through two publications in the Ladies' Home Journal. The articles were a answer to an invitation from the president of Curtis Publishing Company, Edward Bok, as part of a project to improve modern house design. Bok also extended the offer to other architects, but Wright was the sole responder. "A Home in a Prairie Town" and "A Small House with Lots of Room in it" appeared respectively in the February and July 1901 issues of the journal. Although neither of the affordable house plans were ever constructed, Wright received increased requests for similar designs in following years.[37]

Wright's residential designs were "Prairie Houses" because the design is considered to complement the land around Chicago. These houses featured extended low buildings with shallow, sloping roofs, clean sky lines, suppressed chimneys, overhangs and terraces, using unfinished materials. The houses are credited with being the first examples of the "open plan". Windows whenever possible are long, and low, allowing a connection between the interior and nature, outside, that was new to western architecture and reflected the influence of Japanese architecture on Wright . The manipulation of interior space in residential and public buildings are hallmarks of his style.

Commercial buildings in the Prairie style include Unity Temple, the home of the Unitarian Universalist congregation in Oak Park. As a lifelong Unitarian and member of Unity Temple, Wright offered his services to the congregation after their church burned down in 1904. The community agreed to hire him and he worked on the building from 1905 to 1908. Wright later said that Unity Temple was the edifice in which he ceased to be an architect of structure, and became an architect of space. Many architects consider it the world's first modern building, because of its unique construction of only one material: reinforced concrete. This would become a hallmark of the modernists who followed Wright, such as Mies van der Rohe, and even some post-modernists, such as Frank Gehry.

Many examples of this work are in Buffalo, New York as a result of friendship between Wright and Darwin D. Martin, an executive of the Larkin Soap Company. In 1902, the Larkin Company decided to build a new administration building. Wright came to Buffalo and designed not only the Larkin Administration Building (completed in 1904, demolished in 1950), but also homes for three of the company's executives including the Darwin D. Martin House in 1904.

Other Wright houses considered to be masterpieces of the late Prairie Period (1907–1909) are the Frederick Robie House in Chicago and the Avery and Queene Coonley House in Riverside, Illinois. The Robie House, with its soaring, cantilevered roof lines, supported by a 110-foot-long (34 m) channel of steel, is the most dramatic. Its living and dining areas form virtually one uninterrupted space. This building had a profound influence on young European architects after World War I and is sometimes called the "cornerstone of modernism". However, Wright's work was not known to European architects until the publication of the Wasmuth Portfolio.

Midlife controversy and architecture

Family abandonment

Local gossips noticed Wright's flirtations, and he developed a reputation in Oak Park as a man-about-town. His family had grown to six children, and the brood required most of Catherine's attention. In 1903, Wright designed a house for Edwin Cheney, a neighbor in Oak Park, and immediately took a liking to Cheney's wife, Mamah Borthwick Cheney. Mamah Cheney was a modern woman with interests outside the home. She was an early feminist and Wright viewed her as his intellectual equal. The two fell in love, even though Wright had been married for almost 20 years. Often the two could be seen taking rides in Wright's automobile through Oak Park, and they became the talk of the town. Wright's wife, Kitty, sure that this attachment would fade as the others had, refused to grant him a divorce. Neither would Edwin Cheney grant one to Mamah. In 1909, even before the Robie House was completed, Wright and Mamah Cheney eloped to Europe, leaving their own spouses and children behind. The scandal that erupted virtually destroyed Wright's ability to practice architecture in the United States.

Scholars argue that he felt by 1907 that he had done everything he could do with the Prairie Style, particularly from the standpoint of the single family house. Wright was not getting larger commissions for commercial or public buildings, which frustrated him.

What drew Wright to Europe was the chance to publish a portfolio of his work with Ernst Wasmuth, who had agreed in 1909 to publish his work there.[40] This chance also allowed Wright to deepen his relationship with Mamah Cheney. Wright and Cheney left the United States separately in 1910, meeting in Berlin, where the offices of Wasmuth were located.

The resulting two volumes, titled Studies and Executed Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, were published in 1910 and 1911 in two editions, creating the first major exposure of Wright's work in Europe. The work contained more than 100 lithographs of Wright’s designs and was commonly known as the Wasmuth Portfolio.

Wright remained in Europe for one year (though Mamah Cheney returned to the United States a few times) and set up a home in Fiesole, Italy. During this time, Edwin Cheney granted her a divorce, though Kitty still refused to grant one to her husband. After Wright's return to the United States in late 1910, Wright persuaded his mother to buy land for him in Spring Green, Wisconsin. The land, bought on April 10, 1911, was adjacent to land held by his mother's family, the Lloyd-Joneses. Wright began to build himself a new home, which he called Taliesin, by May 1911. The recurring theme of Taliesin also came from his mother's side: Taliesin in Welsh mythology was a poet, magician, and priest. The family motto was Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd which means "The Truth Against the World"; it was created by Iolo Morgannwg who also had a son called Taliesin, and the motto is still used today as the cry of the druids and chief bard of the Eisteddfod in Wales.[41]

More personal turmoil

On August 15, 1914, while Wright was working in Chicago, Julian Carlton, a male servant from Barbados who had been hired several months earlier, set fire to the living quarters of Taliesin and murdered seven people with an axe as the fire burned.[42] The dead included Mamah; her two children, John and Martha; a gardener; a draftsman; a workman; and another workman’s son. Two people survived the mayhem, one of whom helped to put out the fire that almost completely consumed the residential wing of the house. Carlton swallowed acid immediately following the attack in an attempt to kill himself.[42] He was nearly lynched on the spot, but was taken to the Dodgeville jail.[42] Carlton died from starvation seven weeks after the attack, despite medical attention.[42]

In 1922, Wright's first wife, Kitty, granted him a divorce, and Wright was required to wait one year until he married his then-partner, Maude "Miriam" Noel. In 1923, Wright's mother, Anna (Lloyd Jones) Wright, died. Wright wed Miriam Noel in November 1923, but her addiction to morphine led to the failure of the marriage in less than one year. In 1924, after the separation, but while still married, Wright met Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg, at a Petrograd Ballet performance in Chicago. They moved in together at Taliesin in 1925, and soon Olgivanna was pregnant with their daughter, Iovanna. Iovanna was born December 2, 1925 and years later married and divorced Wright's associate Arthur Pieper.

On April 20, 1925, another fire destroyed the bungalow at Taliesin. Crossed wires from a newly installed telephone system were held responsible for the fire, which destroyed a collection of Japanese prints that Wright declared invaluable. Wright estimated the loss at $250,000 to $500,000.[43] Wright rebuilt the living quarters again, naming the home "Taliesin III".

In 1926, Olga's ex-husband, Vlademar Hinzenburg, sought custody of his daughter, Svetlana. In October 1926, Wright and Olgivanna were accused of violating the Mann Act and arrested in Minnetonka, Minnesota.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). where buildings were constructed with precast concrete blocks with a patterned, squarish exterior surface: The Alice Millard House (Pasadena), the John Storer House (West Hollywood), the Samuel Freeman House (Hollywood) and the Ennis House in the Griffith Park area of Los Angeles. During the past two decades the Ennis House has become popular as an exotic, nearby shooting location to Hollywood television and movie makers. He also designed a fifth textile block house for Aline Barnsdall, the Community Playhouse ("Little Dipper"), which was never constructed. Wright's son, Lloyd Wright, supervised construction for the Storer, Freeman and Ennis House. Most of these houses are private residences closed to the public because of renovation, including the George Sturges House (Brentwood) and the Arch Oboler Gatehouse & Studio (Malibu).

Mature Organic Style

During the later 1920s and 1930s Wright's Organic style had fully matured with the design of Graycliff, Fallingwater and Taliesin West.

Graycliff, located just south of Buffalo, NY is an important mid-career (1926–1931) design by Wright; it is a summer estate designed for his long-time patrons, Isabelle and Darwin D. Martin. Created in Wright's high Organic style, Wright wrote in a letter to the Martins that "Coming in the house would be something like putting on your hat and going outdoors." [44] Graycliff consists of three buildings set within 8.4 acres of landscape, also designed by Wright. Its site, high on a bluff overlooking Lake Erie, inspired Wright to create a home that was transparent, with views through the building to the lake beyond. Terraces and cantilevered balconies also encourage lake views, and water features throughout the landscape were designed by Wright to echo the lake as well.

One of Wright's most famous private residences was built from 1934 to 1937—Fallingwater—for Mr. and Mrs. Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr., at Bear Run, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. It was designed according to Wright's desire to place the occupants close to the natural surroundings, with a stream and waterfall running under part of the building. The construction is a series of cantilevered balconies and terraces, using limestone for all verticals and concrete for the horizontals. The house cost $155,000, including the architect's fee of $8,000. Kaufmann's own engineers argued that the design was not sound. They were overruled by Wright, but the contractor secretly added extra steel to the horizontal concrete elements. In 1994, Robert Silman and Associates examined the building and developed a plan to restore the structure. In the late 1990s, steel supports were added under the lowest cantilever until a detailed structural analysis could be done. In March 2002, post-tensioning of the lowest terrace was completed.

Taliesin West, Wright's winter home and studio complex in Scottsdale, AZ, was a laboratory for Wright from 1937 to his death in 1959. Now the home of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and archives, it continues today as the site of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.

Wright is responsible for a series of concepts of suburban development united under the term Broadacre City. He proposed the idea in his book The Disappearing City in 1932, and unveiled a 12-square-foot (1.1 m2) model of this community of the future, showing it in several venues in the following years. He continued developing the idea until his death.

Usonian Houses

Concurrent with the development of Broadacre City, also referred to as Usonia, Wright conceived a new type of dwelling that came to be known as the Usonian House. An early version of the form can be seen in the Malcolm Willey House (1934) in Minneapolis; but the Usonian ideal emerged most completely in the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House (1937) in Madison, Wisconsin. Designed on a gridded concrete slab that integrated the house's radiant heating system, the house featured new approaches to construction, including sandwich walls that consisted of layers of wood siding, plywood cores and building paper, a significant change from typically framed walls. Usonian houses most commonly featured flat roofs and were mostly constructed without basements, completing the excision of attics and basements from houses, a feat Wright had been attempting since the early 20th century.

Intended to be highly practical houses for middle-class clients, and designed to be run without servants, Usonian houses often featured small kitchens — called "workspaces" by Wright — that adjoined the dining spaces. These spaces in turn flowed into the main living areas, which also were characteristically outfitted with built-in seating and tables. As in the Prairie Houses, Usonian living areas focused on the fireplace. Bedrooms were typically isolated and relatively small, encouraging the family to gather in the main living areas. The conception of spaces instead of rooms was a development of the Prairie ideal; as the built-in furnishings related to the Arts and Crafts principles from which Wright's early works grew. Spatially and in terms of their construction, the Usonian houses represented a new model for independent living, and allowed dozens of clients to live in a Wright-designed house at relatively low cost. The diversity of the Usonian ideal can be seen in houses such as the Gregor S. and Elizabeth B. Affleck House (1941) in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, which projects over a ravine; and the Hanna-Honeycomb House (1937) in Palo Alto, California, which features a honeycomb planning grid. Gordon House, completed in 1963, was Wright's last Usonian design.

His Usonian homes set a new style for suburban design that was a feature of countless developers. Many features of modern American homes date back to Wright, including open plans, slab-on-grade foundations, and simplified construction techniques that allowed more mechanization and efficiency in building.

Significant later works

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City occupied Wright for 16 years (1943–1959)[45] and is probably his most recognized masterpiece. The building rises as a warm beige spiral from its site on Fifth Avenue; its interior is similar to the inside of a seashell. Its unique central geometry was meant to allow visitors to easily experience Guggenheim's collection of nonobjective geometric paintings by taking an elevator to the top level and then viewing artworks by walking down the slowly descending, central spiral ramp, which features a floor embedded with circular shapes and triangular light fixtures to complement the geometric nature of the structure. Unfortunately, when the museum was completed, a number of important details of Wright's design were ignored, including his desire for the interior to be painted off-white. Furthermore, the Museum currently designs exhibits to be viewed by walking up the curved walkway rather than walking down from the top level.

The only realized skyscraper designed by Wright is the Price Tower, a 19-story tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It is also one of the two existing vertically-oriented Wright structures (the other is the S.C. Johnson Wax Research Tower in Racine, Wisconsin). The Price Tower was commissioned by Harold C. Price of the H. C. Price Company, a local oil pipeline and chemical firm. It opened to the public in February 1956. On March 29, 2007, Price Tower was designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of the Interior, one of only 20 such properties in the state of Oklahoma.[46]

Other projects

Wright designed over 400 built structures[47] of which about 300 survive as of 2005. Four have been lost to forces of nature: the waterfront house for W. L. Fuller in Pass Christian, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Camille in August 1969; the Louis Sullivan Bungalow of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005; and the Arinobu Fukuhara House (1918) in Hakone, Japan, destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. The Ennis House in California has also been damaged by earthquake and rain-induced ground movement. In January, 2006, the Wilbur Wynant House in Gary, Indiana was destroyed by fire.[48]

In addition, other buildings were intentionally demolished during and after Wright's lifetime, such as: Midway Gardens (1913, Chicago, Illinois) and the Larkin Administration Building (1903, Buffalo, New York) were destroyed in 1929 and 1950 respectively; the Francis Apartments and Francisco Terrace Apartments (both located in Chicago and designed in 1895) were destroyed in 1971 and 1974, respectively; the Geneva Inn (1911) in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin was destroyed in 1970; and the Banff National Park Pavilion (1911) in Alberta, Canada was destroyed in 1939. The Imperial Hotel, in Tokyo (1913) survived the Great Kantō earthquake but was demolished in 1968 due to urban developmental pressures.[49]

One of his projects, Monona Terrace, originally designed in 1937 as municipal offices for Madison, Wisconsin, was completed in 1997 on the original site, using a variation of Wright's final design for the exterior with the interior design altered by its new purpose as a convention center. The "as-built" design was carried out by Wright's apprentice Tony Puttnam. Monona Terrace was accompanied by controversy throughout the 60 years between the original design and the completion of the structure.[50]

Florida Southern College, located in Lakeland, Florida, constructed 12 (out of 18 planned) Frank Lloyd Wright buildings between 1941 and 1958 as part of the Child of the Sun project. It is the world’s largest single-site collection of Frank Lloyd Wright architecture.

A lesser known project that never came to fruition was Wright's plan for Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe.[51] Few Tahoe locals know of the iconic American architect's plan for their natural treasure.

The Kalita Humphreys Theater in Dallas, Texas was Wright's last project before his death.

Wright's last design and first European project

A design that Wright signed off on shortly before his death in 1959 – possibly his last completed design – was realised in late 2007 in the Republic of Ireland.[52] Wright scholar and devotee Marc Coleman worked closely with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, dealing with E. Thomas Casey, the last surviving Foundation architect who trained under Wright. Working with the Foundation, Coleman selected an unbuilt design that was originally commissioned for Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert Wieland and due to be built in Maryland, USA. However, the Wielands subsequently had financial problems and the design was shelved. The Foundation looked through its archive of 380 unbuilt designs and selected 4 for Coleman that were the closest fit for his site. In the end, he chose the Wieland house, largely because the topography of his site is virtually identical to that which the building was originally designed for. The completed house,[53] in only the fourth country in which a Wright design has been realised, is attracting broad interest from the international architectural community. Casey visited the site in County Wicklow, but died before construction began.

Community planning

Frank Lloyd Wright was interested in site and community planning throughout his career. His commissions and theories on urban design began as early as 1900 and continued until his death. He had 41 commissions on the scale of community planning or urban design.[54]

His thoughts on suburban design started in 1900 with a proposed subdivision layout for Charles E. Roberts entitled the "Quadruple Block Plan." This design strayed from traditional suburban lot layouts and set houses on small square blocks of four equal-sized lots surrounded on all sides by roads instead of straight rows of houses on parallel streets. The houses — which used the same design as published in "A Home in a Prairie Town" from the Ladies' Home Journal — were set toward the center of the block to maximize the yard space and included private space in the center. This also allowed for far more interesting views from each house. Although this plan was never realized, Wright published the design in the Wasmuth Portfolio in 1910.[55]

The more ambitious designs of entire communities were exemplified by his entry into the City Club of Chicago Land Development Competition in 1913. The contest was for the development of a suburban quarter section. This design expanded on the Quadruple Block Plan and included several social levels. The design shows the placement of the upscale homes in the most desirable areas and the blue collar homes and apartments separated by parks and common spaces. The design also included all the amenities of a small city: schools, museums, markets, etc.[56] This view of decentralization was later reinforced by theoretical Broadacre City design. The philosophy behind his community planning was decentralization. The new development must be away from the cities. In this decentralized America, all services and facilities could coexist “factories side by side with farm and home.”[57] Notable Community Planning Designs:

- 1900–1903 – Quadruple Block Plan – 24 homes in Oak Park, IL (unbuilt)

- 1909 – Como Orchard Summer Colony – Town site development for new town in the Bitterroot Valley, MT

- 1913 – Chicago Land Development competition – Suburban Chicago quarter section

- 1934–1959 – Broadacre City – Theoretical decentralized city plan – exhibits of large scale model

- 1938 – Suntop Homes also known as Cloverleaf Quadruple Housing Project – commission from Federal Works Agency, Division of Defense Housing – low cost multifamily housing alternative to suburban development

- 1945 – Usonia Homes – 47 homes (3 designed by Wright himself) in Pleasantville, New York

- 1949 – The Acres, also known as Galesburg Country Homes, 5 homes (4 designed by Wright himself) in Charleston Township, Michigan

Japanese art

Though most famous as an architect, Wright was an active dealer in Japanese art, primarily ukiyo-e woodblock prints. He frequently served as both architect and art dealer to the same clients; "he designed a home, then provided the art to fill it".[58] For a time, Wright made more from selling art than from his work as an architect.

Wright first traveled to Japan in 1905, where he bought hundreds of prints. The following year, he helped organize the world's first retrospective exhibition of works by Hiroshige, held at the Art Institute of Chicago.[58] For many years, he was a major presence in the Japanese art world, selling a great number of works to prominent collectors such as John Spaulding of Boston,[58] and to prominent museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[59] He penned a book on Japanese art in 1912.[59]

In 1920, however, rival art dealers began to spread rumors that Wright was selling retouched prints; this combined with Wright's tendency to live beyond his means, and other factors, led to great financial troubles for the architect. Though he provided his clients with genuine prints as replacements for those he was accused of retouching, this marked the end of the high point of his career as an art dealer.[59] He was forced to sell off much of his art collection in 1927 to pay off outstanding debts; the Bank of Wisconsin claimed his Taliesin home the following year, and sold thousands of his prints, for only one dollar a piece, to collector Edward Burr Van Vleck.[58]

Wright continued to collect, and deal in, prints until his death in 1959, frequently using prints as collateral for loans, frequently relying upon his art business to remain financially solvent[59]

The extent of his dealings in Japanese art went largely unknown, or underestimated, among art historians for decades until, in 1980, Julia Meech, then associate curator of Japanese art at the Metropolitan Museum, began researching the history of the museum's collection of Japanese prints. She discovered "a three-inch-deep 'clump of 400 cards' from 1918, each listing a print bought from the same seller—'F. L. Wright'" and a number of letters exchanged between Wright and the museum's first curator of Far Eastern Art, Sigisbert C. Bosch Reitz, in 1918 to 1922.[59] These discoveries, and subsequent research, led to a renewed understanding of Wright's career as an art dealer.

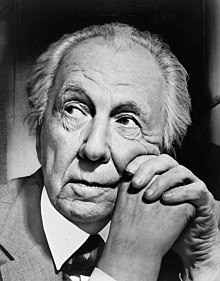

Death and legacy

Turmoil followed Wright even many years after his death on April 9, 1959 while undergoing surgery in Phoenix, Arizona to remove an intestinal obstruction.[60] His third wife, Olgivanna, ran the Fellowship after Wright's death, until her own death in Scottsdale, Arizona in 1985. That year, it was learned that her dying wish had been that Wright, she and her daughter by a first marriage all be cremated and relocated to Scottsdale, Arizona. By then, Wright's body had lain for over 25 years in the Lloyd-Jones cemetery, next to the Unity Chapel, near Taliesin, Wright's later-life home in Spring Green, Wisconsin.[61] Olgivanna's plan called for a memorial garden, already in the works, to be finished and prepared for their remains. Although the garden had yet to be finished, his remains were prepared and sent to Scottsdale where they waited in storage for an unidentified amount of time before being interred in the memorial area. Today, the small cemetery south of Spring Green, Wisconsin and a long stone's throw from Taliesin, contains a gravestone marked with Wright's name but its grave is empty.[62]

Personal style and concepts

Wright's creations took his concern with organic architecture down to the smallest details. From his largest commercial commissions to the relatively modest Usonian houses, Wright conceived virtually every detail of both the external design and the internal fixtures, including furniture, carpets, windows, doors, tables and chairs, light fittings and decorative elements. He was one of the first architects to design and supply custom-made, purpose-built furniture and fittings that functioned as integrated parts of the whole design, and he often returned to earlier commissions to redesign internal fittings. Some of the built-in furniture remains, while other restorations have included replacement pieces created using his plans. His Prairie houses use themed, coordinated design elements (often based on plant forms) that are repeated in windows, carpets and other fittings. He made innovative use of new building materials such as precast concrete blocks, glass bricks and zinc cames (instead of the traditional lead) for his leadlight windows, and he famously used Pyrex glass tubing as a major element in the Johnson Wax Headquarters. Wright was also one of the first architects to design and install custom-made electric light fittings, including some of the very first electric floor lamps, and his very early use of the then-novel spherical glass lampshade (a design previously not possible due to the physical restrictions of gas lighting).

As Wright's career progressed, so did the mechanization of the glass industry. Wright fully embraced glass in his designs and found that it fit well into his philosophy of organic architecture. Glass allowed for interaction and viewing of the outdoors while still protecting from the elements. In 1928, Wright wrote an essay on glass in which he compared it to the mirrors of nature: lakes, rivers and ponds. One of Wright's earliest uses of glass in his works was to string panes of glass along whole walls in an attempt to create light screens to join together solid walls. By utilizing this large amount of glass, Wright sought to achieve a balance between the lightness and airiness of the glass and the solid, hard walls. Arguably, Wright's best-known art glass is that of the Prairie style. The simple geometric shapes that yield to very ornate and intricate windows represent some of the most integral ornamentation of his career.[63]

Wright responded to the transformation of domestic life that occurred at the turn of the 20th century, when servants became a less prominent or completely absent from most American households, by developing homes with progressively more open plans. This allowed the woman of the house to work in her 'workspace', as he often called the kitchen, yet keep track of and be available for the children and/or guests in the dining room. Much of modern architecture, including the early work of Mies van der Rohe, can be traced back to Wright's innovative work.

Wright also designed some of his own clothing. His fashion sense was unique, and he usually wore expensive suits, flowing neckties, and capes. Wright drove a custom yellow 'raceabout' in the Prairie years, a red Cord convertible in the 1930s, and a famously customized 1940 Lincoln for many years. He earned many speeding tickets in each of his vehicles. [citation needed]

Colleagues and influences

Wright rarely credited any influences on his designs, but most architects, historians and scholars agree he had five major influences:

- Louis Sullivan, whom he considered to be his 'Lieber Meister' (dear master),

- Nature, particularly shapes/forms and colors/patterns of plant life,

- Music (his favorite composer was Ludwig van Beethoven),

- Japanese art, prints and buildings,

- Froebel Gifts [citation needed]

He also routinely claimed the architects and architectural designers who were his employees' work as his own design and claimed that the rest of the Prairie School architects were merely his followers, imitators and subordinates.[64] But, as with any architect, Wright worked in a collaborative process and drew his ideas from the work of others. In his earlier days, Wright worked with some of the top architects of the Chicago School, including Sullivan. In his Prairie School days, Wright's office was populated by many talented architects including William Eugene Drummond, John Van Bergen, Isabel Roberts, Francis Barry Byrne, Albert McArthur, Marion Mahony Griffin and Walter Burley Griffin.

The Czech-born architect Antonin Raymond, recognized as the father of modern architecture in Japan, worked for Wright at Taliesin and led the construction of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He subsequently stayed in Japan and opened his own practice. Rudolf Schindler also worked for Wright on the Imperial hotel. His own work is often credited as influencing Wright's Usonian houses. Schindler's friend Richard Neutra also worked briefly for Wright and became an internationally successful architect.

Later in the Taliesin days, Wright employed many architects and artists who later become notable, such as Aaron Green, John Lautner, E. Fay Jones, Henry Klumb and Paolo Soleri in architecture and Santiago Martinez Delgado in the arts. As a young man, actor Anthony Quinn applied to study with Wright at Taliesin. However, Wright suggested that he first take voice lessons to help overcome a speech impediment.

Bruce Goff never worked for Wright but maintained correspondence with him. Their works can be seen to parallel each other.

Recognition

Later in his life and well after his death in 1959, Wright received much honorary recognition for his lifetime achievements. He received Gold Medal awards from The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1941 and the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1949. He was awarded the Franklin Institute's Frank P. Brown Medal in 1953. He received honorary degrees from several universities (including his "alma mater", the University of Wisconsin) and several nations named him as an honorary board member to their national academies of art and/or architecture. In 2000, Fallingwater was named "The Building of the 20th century" in an unscientific "Top-Ten" poll taken by members attending the AIA annual convention in Philadelphia. On that list, Wright was listed along with many of the USA's other greatest architects including Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei, Louis Kahn, Philip Johnson and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and he was the only architect who had more than one building on the list. The other three buildings were the Guggenheim Museum, the Frederick C. Robie House and the Johnson Wax Building.

In 1992, The Madison Opera in Madison, Wisconsin commissioned and premiered the opera Shining Brow, by composer Daron Hagen and librettist Paul Muldoon based on events early in Wright's life. The work has since received numerous revivals. In 2000, Work Song: Three Views of Frank Lloyd Wright, a play based on the relationship between the personal and working aspects of Wright's life, debuted at the Milwaukee Repertory Theater.

In 1966, the United States Postal Service honored Wright with a Prominent Americans series 2¢ postage stamp.

Family

Frank Lloyd Wright was married three times and fathered seven children, four sons and three daughters. He also adopted Svetlana Milanoff, the daughter of his third wife, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright.[65]

His wives were:

- Catherine "Kitty" (Tobin) Wright (1871–1959). Socialite and Social Worker. Married June 1889; divorced November 1922.

- Maude "Miriam" (Noel) Wright (1869–1930). Artist. Married November, 1923; divorced August 1927.

- Olga Ivanovna "Olgivanna" (Lazovich Milanoff) Lloyd Wright (1897–1985). Dancer and writer. Married August 1928.

One of Wright's sons, Frank Lloyd Wright Jr., known as Lloyd Wright, was also a notable architect in Los Angeles. Lloyd Wright's son (and Wright's grandson), Eric Lloyd Wright, is currently an architect in Malibu, California where he has a practice of mostly residences, but also civic and commercial buildings.

Another son and architect, John Lloyd Wright, invented Lincoln Logs in 1918, and practiced extensively in the San Diego area. John's daughter, Elizabeth Wright Ingraham, is an architect in Colorado Springs, Colorado. She is the mother of Christine, an interior designer in Connecticut, and Catherine, an architecture professor at the Pratt Institute.[66]

The Oscar-winning actress Anne Baxter was Wright's granddaughter. Baxter was the daughter of Catherine Baxter, a child born of Wright's first marriage. Anne's daughter, Melissa Galt, currently lives and works in Atlanta as an interior designer.[66]

His adopted daughter Svetlana (daughter of Olgivanna) and her son Daniel died in an automobile accident in 1946. Her widower, William Wesley Peters, was later briefly married to Svetlana Alliluyeva, the youngest child and only daughter of Joseph Stalin. They divorced after she could not adjust to the communal lifestyle of the Wright communities, which she compared to life in the Soviet Union under her father, and because of the constant interference of Wright's widow. Peters served as Chairman of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation from 1985 to 1991.

A great-grandson of Wright, S. Lloyd Natof, currently lives and works in Chicago as a master woodworker who specializes in the design and creation of custom wood furniture.[67]

Archives

Photographs and other archival materials are held by the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Herbert and Katherine Jacobs Residence and Frank Lloyd Wright Records, 1924–1974, Collection includes drawings, correspondence, and other materials documenting the construction of two homes for the Jacobs as well as research files on Wright's life. The Frank Lloyd Wright in Michigan Collection, 1945–1988, consists of research documents, including photocopied correspondence between Wright and his clients, used for the book "Frank Lloyd Wright in Michigan." The Wrightiana Collection, c. 1897–1997 (bulk 1949–1969), includes a variety of printed materials and photographs about Wright and his projects. The Joseph J. Bagley Cottage Collection, c. 1916–1925, contains photographs and drawings documenting the Bagley cottage which was completed in 1916.

The architect's personal archives are located at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. The Frank Lloyd Wright archives include photographs of his drawings, indexed correspondence beginning in the 1880s and continuing through Wright's life, and other ephemera. The Getty Research Center in Los Angeles, California, also has copies of Wright's correspondence and photographs of his drawings in their "Frank Lloyd Wright Special Collection". Wright's correspondence is indexed in An Index to the Taliesin Correspondence, ed. by Professor Anthony Alofsin, which is available at larger libraries.

Selected works

- Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, Oak Park, Illinois, 1889–1909

- William H. Winslow House, River Forest, Illinois, 1894

- Ward Winfield Willits Residence, and Gardener’s Cottage and Stables, Highland Park, Illinois, 1901

- Dana-Thomas House, Springfield, Illinois, 1902

- Larkin Administration Building, Buffalo, New York, 1903 (demolished, 1950)

- Darwin D. Martin House, Buffalo, New York, 1903–1905

- Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1904

- Frederick C. Robie Residence, Chicago, Illinois, 1909

- Taliesin I, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1911

- Midway Gardens, Chicago, Illinois, 1913 (demolished, 1929)

- Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, 1923 (demolished, 1968; entrance hall reconstructed at Meiji Mura near Nagoya, Japan, 1976)

- Hollyhock House (Aline Barnsdall Residence), Los Angeles, California, 1919–1921

- Ennis House, Los Angeles, California, 1923

- Taliesin III, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1925

- Graycliff. Buffalo, NY 1926

- Fairhope (Richard Lloyd Jones Residence, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1929

- Fallingwater (Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. Residence), Bear Run, Pennsylvania, 1935–1937

- First Jacobs House, 1936–1937

- Johnson Wax Headquarters, Racine, Wisconsin, 1936

- Herbert F. Johnson Residence ("Wingspread"), Wind Point, WI, 1937

- Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1937

- Usonian homes, various locations, 1930s–1950s

- Child of the Sun, Florida Southern College, Lakeland, Florida, 1941–1958

- First Unitarian Society of Madison, Shorewood Hills, Wisconsin, 1947

- V. C. Morris Gift Shop, San Francisco, California, 1948

- Price Tower, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 1952–1956

- Beth Sholom Synagogue, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1954

- Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1956–1961

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York, 1956–1959

- Kentuck Knob, Ohiopyle, Pennsylvania, 1956

- The Illinois, mile-high tower in Chicago, 1956 (unbuilt)

- Marshall Erdman Prefab Houses, various locations, 1956–1960

- Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, 1956–1961

- Marin County Civic Center, San Rafael, CA, 1957–1966

- Gammage Auditorium, Tempe, Arizona, 1959–1964

See also

- Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

- Wasmuth Portfolio

- Richard Bock

- Roman brick

- Jaroslav Joseph Polivka

- Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio

- Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

- Frank Lloyd Wright-Prairie School of Architecture Historic District

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works by location

- Broadacre City

- Fallingwater

References

Works Cited in Article

- ^ a b Brewster, Mike (2004-07-28). "Frank Lloyd Wright: America's Architect". Business Week. The McGraw-Hill Companies. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ An Autobiography, by Frank Lloyd Wright, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York City, 1943, p. 51

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, by Meryle Secrest, University of Chicago Press, 1992, p.72

- ^ Phi Delta Theta list of Famous Phis, accessed on May 26. 2008

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, by Meryle Secrest, p. 82

- ^

Wright, Frank Lloyd (2005). Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography. Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate Communications. pp. 60–63. ISBN 076493243.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "A brief Biography". Wright’s Life + Work. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ O'Gorman, Thomas J. (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright's Chicago. San Diego: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 1-59223-127-6.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 86.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 89-94.

- ^

Tafel, Edgar (1985). Years With Frank lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. p. 31. ISBN 0-486-24801-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Saint, Andrew (May 2004). "Frank Lloyd Wright and Paul Mueller: the architect and his builder of choice" (PDF). Architectural Research Quarterly. 7 (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 157–167. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ a b Wright 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust (2001). Zarine Weil (ed.). Building A Legacy: The Restoration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park Home and Studio. San Francisco: Pomegranite. p. 4. ISBN 0-7649-1461-8.

- ^ a b

Gebhard, David (2006). Purcell & Elmslie: Prairie Progressive Architects. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith. p. 32. ISBN 1-4236-0005-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wright 2005, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Lind, Carla (1996). Lost Wright: Frank Lloyd Wright's Vanished Masterpieces. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 40–43. ISBN 0-684-81306-8.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust 2001, p. 7.

- ^ O'Gorman 2004, pp. 38-54.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 101

- ^ Tafel 1985, p. 41

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 112.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 118-119.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Brooks, H. Allen (2005). "Architecture: The Prairie School". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Cassidy, Victor M. (21 October 2005). "Lost Woman". Artnet Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Marion Mahony Griffin (1871-1962)". From Louis Sullivan to SOM: Boston Grads Go to Chicago. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1996. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ O'Gorman 2004, pp. 56-109.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 116

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 114-116.

- ^

Goldberger, Paul (9 march 2009). "Toddlin' Town: Daniel Burnham's great Chicago Plan turns one hundred". The Sky Line. The New Yorker. Retrieved 26 march 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust 2001, pp. 6-9.

- ^ My Father: Frank Lloyd Wright, by John Lloyd Wright; 1992; page 35

- ^ a b Clayton, Marie (2002). Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide. Running Press. pp. 97–102. ISBN 0-7624-1324-7.

- ^ Sommer, Robin Langley (1997). "Frank W. Thomas House". Frank Lloyd Wright: A Gatefold Portfolio. Honk Kong: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-0463-5.

- ^ O'Gorman 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, by Meryle Secrest, Alfred A. Knopf, 1993, p. 202

- ^ "Home Country". Unitychapel.org. 2005-07-01. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ a b c d BBC News article: "Mystery of the murders at Taliesin".

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, by Meryle Secrest, p. 315–317. "$500,000 Fire in Bungalow,"The New York Times, April 22, 1925

- ^ State University of New York at Buffalo Archives http://ubdigit.buffalo.edu/collections/lib/lib-ua/lib-ua001_DDMartin.php

- ^ Guggenheim Museum – History[dead link]

- ^ National Park Service – National Historic Landmarks Designated, April 13, 2007

- ^ The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog, by William Allin Storrer, University of Chicago Press, 1992 (third edition)

- ^ "Preservation Online: Today's News Archives: Fire Guts Rare FLW House in Indiana". Nationaltrust.org. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Berstein, Fred A. "Near Nagoya, Architecture From When the East Looked West," New York Times. April 2, 2006.

- ^ Monona Terrace Convention Center, history web page

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe". Tahoelocals.com. 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ "Wright On". constructireland.ie. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Wright On – Late 1950s Frank Lloyd Wright design realised in Wicklow (Retrieved 18 November 2009)

- ^ Wrightscapes: Frank Lloyd Wright's Landscape Designs, Charles E. and Berdeana Aguar, McGraw-Hill, 2002, p.344

- ^ Wrightscapes:Frank Lloyd Wright's Landscape Designs, Charles E. and Berdeana Aguar, McGraw-Hill, 2002, pp. 51–56

- ^ "Undoing the City: Frank Lloyd Wright's Planned Communities," American Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Oct., 1972), p. 544

- ^ "Undoing the City: Frank Lloyd Wright's Planned Communities," American Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Oct., 1972), p. 542

- ^ a b c d Cotter, Holland. "Seeking Japan's Prints, Out of Love and Need." New York Times. 6 April 2001.

- ^ a b c d e Reif, Rita. "Frank Lloyd Wright's Love of Japanese Prints Helped Pay the Bills." New York Times. 18 March 2001.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright Dies; Famed Architect Was 89". nytimes.com<!. 1959-04-10. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ The Unity Chapel, designed by Joseph Silsbee, should not be confused with the much larger and vastly more famous Unity Temple, designed by Wright and located in Oak Park, IL. Wright was the draftsman for the design of the Unity Chapel.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, Meryle Secrest, University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright's Glass Designs, Carla Lind, Pomegranate Artbooks/Archetype Press, 1995.

- ^ "The Magic of America, Marion Mahony Griffin

- ^ ascedia.com. "Taliesin Preservation, Inc. – Frank Lloyd Wright – FAQ's". Taliesinpreservation.org. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mann, Leslie (2008-02-01). "Reflecting pools: Descendants follow in Frank Lloyd Wright's footsteps". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ^ "The Short List". Chicago Magazine. November 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

Selected books and articles on Wright’s philosophy

- An Autobiography, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1943, Duell, Sloan and Pearce / 2005, Pomegranate; ISBN 0-7649-3243-8)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: A Primer on Architectural Principles, by Robert McCarter (1991, Princeton Architectural Press; ISBN 1878271261)

- Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Homes: Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes, by John Sergeant (1984, Watson-Guptill; ISBN 0823071782)

- Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Homes (Wright at a Glance Series), by Carla Lind (1994, Pomegranate Communications; ISBN 1566409985)

- "In the Cause of Architecture," Architectural Record, March, 1908, by Frank Lloyd Wright. Published in Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, vol. 1 (1992, Rizzoli; ISBN 0-8478-1546-3)

- Natural House, The, by Frank Lloyd Wright (1954, Horizon Press; ISBN 0517020785)

- Taliesin Reflections: My Years Before, During, and After Living with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Earl Nisbet (2006, Meridian Press; ISBN 0-9778951-0-6)

- Truth Against the World: Frank Lloyd Wright Speaks for an Organic Architecture, ed. by Patrick Meehan (1987, Wiley; ISBN 0471845094)

- Understanding Frank Lloyd Wright's Architecture, by Donald Hoffman (1995, Dover Publications; ISBN 048628364X)

- Usonia : Frank Lloyd Wright's Design for America, Alvin Rosenbaum (1993, Preservation Press; ISBN 0891332014)

- Frank Lloyd Wright, by Daniel Treiber (2008, Birkhäuser Basel, 2nd, updated edition; ISBN 978-3764386979)

Biographies of Wright

- Frank Lloyd Wright: Architecture, man in possession of his earth, by Iovanna Lloyd Wright (1962, Doubleday; OCLC 31514669)

- Many Masks, by Brendan Gill (1987, Putnam; ISBN 0399132325)

- Frank Lloyd Wright, by Ada Louise Huxtable (2004, Lipper/Viking; ISBN 0670033421)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: a Biography, by Meryle Secrest (1992, Knopf; ISBN 0394564367)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and Architecture, by Robert Twombly (1979, Wiley; ISBN 0471034002)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: by Vaccaro, Tony, (2002, Kultur-unterm-Schirm)

- The Fellowship: The Untold Story of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, by Roger Friedland and Harold Zellman (2006, Regan Books; ISBN 0060393882)

- Loving Frank, by Nancy Horan, (2008, Random House, Inc; ISBN 0345494997)

Selected survey books on Wright’s work

- Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, The, by Neil Levine (1996, Princeton University Press; ISBN 0691033714)

- Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog, The, by William Allin Storrer (2007 updated 3rd. ed., University of Chicago Press; ISBN 0-226-77620-4)

- Frank Lloyd Wright, by Robert McCarter (1997, Phaidon, London; ISBN 0 7148 31484 (hardback), ISBN 0714838543 (paperback))

- Frank Lloyd Wright: America’s Master Architect, by Kathryn Smith (1998, Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.); ISBN 0789202875)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: Architect, by the Museum of Modern Art (1994, ISBN 087070642X)

- Frank Lloyd Wright Companion, The, by William Allin Storrer (2006 Rev. Ed., University of Chicago Press; ISBN 0-226-77621-2)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: Masterworks, by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer (1993, Rizzoli; ISBN 0847817156)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: Building for Democracy, by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer (2004, Taschen; ISBN 3-8228-2757-6)

- Wrightscapes: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Landscape Designs, by Charles and Berdeana Aguar (2003, McGraw-Hill; ISBN 007140953X)

- Wright Space: Pattern and Meaning in Frank Lloyd Wright's Houses by Grant Hildebrand (1991, University of Washington Press; ISBN 0295970057)

- Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide, by Thomas A. Heinz (1999, Academy Editions; ISBN 0-8101-2244-8)

- Frank Lloyd Wright's Glass Designs, by Carla Lind (1995, Pomegranate; ISBN 0876544685)

- The Gardens of Frank Lloyd Wright, introduction by James van Sweden, Frances Linden 2009 ISBN 978-0-711229678

- Frank Lloyd Wright Complete Works 1943–1959, by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer and Peter Gössel (editor) (2009, Taschen; ISBN 978-3-8228-5770-0). First in a series of three monographs featuring all of Wright's 1,100 designs, both realized and unrealized.

Selected books about specific Wright projects

- Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E. J. Kaufmann, and America's Most Extraordinary House, by Franklin Toker (2003, Knopf; ISBN 1400040264)

External links

- Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Official Website

- Frank Lloyd Wright, Wisconsin Historical Society

- Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

- Template:Worldcat id

- Frank Lloyd Wright YouTube

- Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust – FLW Home and Studio, Robie House

- Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture

- Frank Lloyd Wright Wisconsin Heritage Tourism Program

- Frank Lloyd Wright – PBS documentary by Ken Burns and resources

- American System-Built Houses by Frank Lloyd Wright – an overview with slideshow.

- Frank Lloyd Wright. Designs for an American Landscape 1922–1932

- Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Recorded by the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Complete list of Wright buildings by location

- Sullivan, Wright, Prairie School, & Organic Architecture

- Audio interview with Martin Filler on Frank Lloyd Wright from The New York Review of Books

- Article on the 50th anniversary of Wright's only gas station.

- Frank Lloyd Wright and Quebec

- Frank Lloyd Wright interviewed by Mike Wallace on The Mike Wallace Interview recorded September 1 & 28, 1957

- Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

- 1867 births

- 1959 deaths

- American architects

- American furniture designers

- American Christian pacifists

- American Unitarians

- Architectural theoreticians

- American people of English descent

- Modernist architects

- Organic architecture

- People from Chicago, Illinois

- People from Oak Park, Illinois

- People from Richland County, Wisconsin

- People from Scottsdale, Arizona

- Prairie School

- American stained glass artists and manufacturers

- University of Wisconsin–Madison alumni

- American people of Welsh descent

- Architects from Wisconsin

- Pantheists

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal