Civil Air Patrol: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

'''Encampment''' |

'''Encampment''' |

||

: Encampment is typically is a ten day- 3 weeks basic training for Cadets. While curriculum varies from wing to wing it usually consists of physical training, class on leadership and aerospace as well as possible Emergency Service, survival skills, First Aid, rappelling, and marksmanship training. |

|||

: Civil Air Patrol's core cadet activity is the encampment. Tyically a week-long event, cadets are put into an intense, military-structured environment with physically and mentally demanding tasks and required classes and activities. These classes include aerospace education, Air Force organization, cadet programs, and drug demand reduction. Activities include the classroom courses, physical training, and drill & ceremonies. Encampments are usually held at the wing (state) level and when available, usually on military installations with military support. |

|||

'''Region Cadet Leadership Schools''' |

'''Region Cadet Leadership Schools''' |

||

: The Region Cadet Leadership Schools (RCLS) provide training to increase knowledge, skills, and attitudes as they pertain to leadership and management. To be eligible to attend, cadets must be serving in, or preparing to enter, cadet leadership positions within their squadron. RCLS’s are conducted at region level, or at wing level with region approval. |

: The Region Cadet Leadership Schools (RCLS) provide training to increase knowledge, skills, and attitudes as they pertain to leadership and management. To be eligible to attend, cadets must be serving in, or preparing to enter, cadet leadership positions within their squadron. RCLS’s are conducted at region level, or at wing level with region approval. |

||

Revision as of 01:49, 6 March 2008

The Civil Air Patrol (CAP) is the civilian auxiliary of the United States Air Force (USAF). It was created on 1 December, 1941 by Administrative Order 9, with Maj. Gen. John F. Curry as the first National Commander. Civil Air Patrol is credited with sinking at least two German U-boats during World War II. Today, CAP is no longer called on to destroy submarines, but is instead a benevolent entity dedicated to aerospace education, cadet programs, and national service. It is a volunteer organization with an aviation-minded membership that includes people from all backgrounds and walks of life. It performs three congressionally assigned key missions: emergency services (including search and rescue), aerospace education for youth and the general public, and cadet programs for teenage youth. In addition, it has recently been tasked with Homeland Security and courier service missions. CAP also performs non-auxiliary missions for various governmental and private agencies, such as local law enforcement and the American Red Cross.

During World War II, the Civil Air Patrol was seen as a way to use America's civil aviation resources to aid the war effort instead of grounding them (as was the case in Great Britain). The organization eagerly assumed many missions including anti-submarine patrol and warfare, border patrols and courier services. The Civil Air Patrol sighted 173 enemy submarines and sank two. Despite being a volunteer force that was largely untrained in combat and military science, the organization's performance far exceeded expectations.

After the end of World War II the Civil Air Patrol became the civilian auxiliary of the United States Air Force. The incorporation charter declared that CAP would never again be involved in direct combat activities, but would be of a benevolent nature. CAP actively performs about 90% of inland search and rescue missions within the United States. After the September 11, 2001 attacks, Civil Air Patrol aircraft provided the first aerial pictures of the World Trade Center site, and also flew transport missions bringing donated blood to New York City.

History

Origin

The general idea of the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) originated with a collective brainstorm of pilots and aviators during the start of World War II. In the later half of the 1930s, the Axis Powers became a threat to the United States, its allies and its interests. As the Axis steadily took control of the greater part of Europe and South-East Asia, aviation-minded Americans noticed a trend: in all of the conquered countries and territories, civil aviation was more or less halted in order to reduce the risk of sabotage. Countries that were directly involved in the conflict strictly regulated general aviation, allowing military flights only. American aviators did not wish to see the same fate befall themselves, but realized that if nothing was done to convince the federal government that civil aviation could be of direct and measurable benefit to the imminent war effort, the government would likely severely limit general aviation.

The concrete plan for a general aviation organization designed to aid the U.S. military at home was envisaged in 1938 by Gill Robb Wilson. Wilson, then aviation editor of The New York Herald Tribune, was on assignment in Germany prior to the outbreak of World War II. He took note of the actions and intentions of the Nazi government and its tactic of grounding all general aviation. Upon returning, he reported his findings to the New Jersey governor, advising that an organization be created that would use the civil air fleet of New Jersey as an augmentative force for the war effort that seemed impending. The plan was approved, and with the backing of Chief of the Army Air Corps General Henry H. "Hap" Arnold and the Civil Aeronautics Authority, the New Jersey Civil Air Defense Services (NJCADS) was formed. The plan called for the use of single-engine aircraft for liaison work, as well as coastal and infrastructure patrol. General security activities regarding aviation were also made the responsibility of the NJCADS.

Other similar groups were organized, such as the AOPA Civil Air Guard and the Florida Defense Force.

During this time, the Army Air Corps and the Civil Aeronautics Administration initiated two separate subprograms. The first was the introduction of a civilian pilot refresher course and the Civilian Pilot Training Program. The motive behind this step was to increase the pool of available airmen who could be placed into military service if such a time came. The second step was concentrated more on the civil air strength of the nation in general and called for the organization of civilian aviators and personnel in such a way that the collective manpower and know-how would assist in the seemingly inevitable all-out war effort. This second step was arguably the Federal government's blessing towards the creation of the Civil Air Patrol. It was followed by a varied and intense debate over organizational logistics, bureaucracy and other administrative and practical details.

Thomas Beck, who was at the time the Chairman of the Board of the Crowell-Collier Publishing Company, compiled an outline and plan to present to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that would lead up to the organization of the nation's civilian air power. Beck received peer guidance and support from Guy Gannett, the owner of a Maine newspaper chain. On 20 May 1941, the Office of Civilian Defense was created, with former New York City mayor and World War I pilot Fiorello H. LaGuardia as the director. Wilson, Beck, and Gannett presented their plan for a national civil air patrol to LaGuardia, and he approved the idea. He then appointed Wilson, Beck, and Gannett to form the so-called "blueprint committee" and charged them with organizing the national aviation resources on a national scale.

By October of 1941 the plan was completed. The remaining tasks were chiefly administrative, such as the appointment of wing commanders, and Wilson left his New York office and traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak with Army officials as the Civil Air Patrol's first executive officer. General Henry "Hap" Arnold organized a board of top military officers to review Wilson's final plan. The board, which included General George E. Stratemeyer (presiding officer of the board), Colonel Harry H. Blee, Major Lucas P. Ordway, Jr., and Major A.B. McMullen, reviewed the plan set forward by Wilson and his colleagues and evaluated the role of the War Department as an agency of the Office of Civilian Defense. The plan was approved and the recommendation was made that Army Air Forces officers assist with key positions such as flight training and logistics.

With the approval of the Army Air Corps, Director LaGuardia signed the order that created the Civil Air Patrol on December 1 1941.

World War II

On December 1 1941, Director LaGuardia published Administrative Order 9. This order outlined the Civil Air Patrol's organization and named its first national commander as Major General John F. Curry. Wilson was officially made the executive officer of the new organization. Additionally, Colonel Harry H. Blee was appointed the new operations director.

The very fear that sparked the Civil Air Patrol "movement"—that general aviation would be halted—became a reality when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. On 8 December 1941, all civil aircraft, with the exception of airliners, were grounded. This ban was lifted two days later (with the exception of the entire West Coast) and things went more or less back to normal.

Earle E. Johnson took notice of the lack of security at general aviation airports despite the attack on Pearl Harbor. Seeing the potential for light aircraft to be used by saboteurs, Johnson took it upon himself to prove how vulnerable the nation was. Johnson took off in his own aircraft from his farm airstrip near Cleveland, Ohio, taking three small sandbags with him. Flying at 500 feet (~150 meters), Johnson dropped a sandbag on each of three war plants and then returned to his airstrip. The next morning he notified the factory owners that he had "bombed" their facilities. The CAA apparently got Johnson's message and grounded all civil aviation until better security measures could be taken. Not surprisingly, the Civil Air Patrol's initial membership increased along with the new security.[1]

With America's entrance into World War II, German U-boats began to operate along the East Coast. Their operations were very effective, sinking a total of 204 vessels by September of 1942. The Civil Air Patrol's top leaders requested that the War Department give them the authority to directly combat the U-boat threat. The request was initially opposed, for the CAP was still a young and inexperienced organization. However, with the alarming numbers of ships being sunk by the U-boats, the War Department finally agreed to give CAP a chance.

On 5 March 1942, under the leadership of the newly promoted National Commander Johnson (the same Johnson that had "bombed" the factories with sandbags), the Civil Air Patrol was given authority to operate a coastal patrol at two locations along the East Coast. They were given a time frame of 90 days to prove their worth. The CAP's performance was outstanding, and before the 90 day period was over, the coastal patrol operations were authorized to expand in both duration and territory.[2]

Coastal Patrol

Originally, the Coastal Patrol was to be unarmed and strictly reconnaissance. The air crews of the patrol aircraft were to keep in touch with their bases and notify the Army Air Forces and Navy in the area when a U-boat was sighted, and to remain in the area until relieved. This policy was reviewed, however, when the Civil Air Patrol encountered a turkey shoot opportunity. In May 1942, a CAP crew consisting of "Doc" Rinker and Tom Manning were flying a coastal patrol mission off Cape Canaveral when they spotted a German U-boat. The U-boat crew also spotted the aircraft, but not knowing that it was unarmed, attempted to flee. The U-boat became stuck on a sandbar, and consequently became an easy target.

Rinker and Manning radioed to mission base the opportunity and circled the U-boat for more than half an hour. Unfortunately, by the time that Army Air Force bombers came to destroy the U-boat, the vessel had dislodged itself and had escaped to deep waters. As a result of this incident, CAP aircraft were authorized to be fitted with bombs and depth charges. Some of CAP's larger aircraft had the capability to carry 325 pounds (147 kg) in depth charges or bombs. Most light aircraft, however, could only carry 100 pounds (45 kg), which was equivalent to one small bomb. In some cases, the bomb's flight fins had to be partially removed so they would be able to fit underneath the wing of a light aircraft.

One squadron's insignia of the time was a cartoon drawing of a small plane sweating and straining to carry a large bomb. This insignia has become popular throughout CAP.

The CAP's first kill was claimed with one of the larger aircraft. The Grumman G-44 Widgeon, armed with two depth charges and crewed by Captain Johnny Haggins and Major Wynant Farr, was scrambled when another CAP patrol radioed that they had encountered an enemy submarine but were returning to base (due to low fuel). After scanning the area, Farr spotted the U-boat cruising beneath the surface of the waves. Unable to determine accurately the depth of the vessel, Haggins and Ferr radioed the situation back to base and followed the enemy in hopes that it would rise to periscope depth. For three hours, the crew shadowed the submarine, but it didn't rise. Just as Haggins was about to return to base, the U-boat rose to periscope depth, and Haggins swung the aircraft around, aligned with the submarine and dove to 100 feet (30 m). Farr released one of the two depth charges, literally blowing the submarine's front out of the water. As it left an oil slick, Farr released the second charge and debris appeared on the surface, confirming the U-boat's demise and the Civil Air Patrol's first kill.

The kill was perhaps the crowning achievement for CAP's Coastal Patrol, which continued to operate for about 18 months (from March 5 1942 to August 31 1943) before being officially retired. In this time frame, the Coastal Patrol reported 173 U-boats, 57 of which were attacked by CAP aircraft with 83 ordnance pieces and two of which were confirmed sunk. In addition, the Coastal Patrol flew 86,865 missions, logging over 244,600 hours. Coastal Patrol aircraft reported 91 ships in distress and played a key role in rescuing 363 survivors of U-boat attacks. 117 floating mines were reported and 5,684 convoy missions were flown for the Navy.[3]

Border Patrol

Between July 1942 and April 1944, the Civil Air Patrol Southern Liaison Patrol was given the task of patrolling the border between Brownsville, Texas, and Douglas, Arizona. The Southern Liaison Patrol logged approximately 30,000 flight hours and patrolled roughly 1,000 miles (~1,610 kilometers) of the land separating the United States and Mexico. Southern Liaison Patrol tasks included looking for indications of spy or saboteur activity and were similar to counterdrug missions executed by Civil Air Patrol today. Aircraft piloted by the Southern Liaison Patrol often flew low enough to read the license plates on suspicious automobiles traveling in the patrol region.

During its time of operation the Southern Liaison Patrol, more commonly known as the "CAP Border Patrol", reported almost 7,000 out-of-the-ordinary activities and 176 suspicious aircraft' descriptions and direction. During the entire operating period, only two members lost their lives. Considering the fact that the Border Patrol was one of the most dangerous missions CAP flew (along with Coastal Patrol), this is an exceptionally low number.

In a return to its World War II roots, CAP is currently assisting the US Border Patrol with flights along the US-Mexico border to assist in locating illegal immigrants and to route emergency services resources to aid those in distress.[4]

Target towing

In March of 1942, CAP aircraft began towing targets for air-to-air (fighters) and ground-to-air (anti-aircraft batteries) gunnery practice. Targets would be trailed behind the aircraft (similar to the way an aircraft trails a banner) to simulate strafing attacks. CAP aircraft would also climb to various altitudes and would trail two targets for heavy AA guns to use for practice. Although uncommon, an antiaircraft round would occasionally hit the aircraft. Surprisingly, no deaths resulted from errant shots.

Similarly, CAP aircraft also flew night missions to provide tracking practice for the crews of searchlights and radar units. These missions were dangerous in the sense that the pilot ran the risk of accidentally looking into the glare of a searchlight while performing evasive maneuvers, which would blind and disorient him. Such was the case of Captain Raoul Souliere, who lost his life after he went into a steep dive; witnesses surmised that he looked into the glare of a spotlight that had locked on to him, became disoriented, and did not realize he was in a dive.

Despite the dangerous nature of these missions, fatalities and accidents were rare. CAP flew target missions for three years with 7 member fatalities, 5 serious injuries and 23 aircraft lost. A total of 20,593 towing and tracking missions were flown.[5]

Search and Rescue operations (SAR)

During the period between January 1 1942, and January 1 1946, the Civil Air Patrol flew over 24,000 hours of federal- and military-assigned search and rescue missions in addition to thousands of hours of non-assigned SAR missions. These missions were a huge success, and in one particular week during February of 1945, CAP SAR air crews found seven missing Army and Navy aircraft.

The Civil Air Patrol had several decisive advantages over the Army Air Forces in terms of SAR ability. First, because CAP was using civilian aircraft, they could fly lower and slower than the aircraft of the AAF. Second, unlike AAF pilots, CAP pilots tended to be local citizens and therefore knew the terrain much better. Third, CAP utilized ground teams which would travel to the suspected crash site (often by foot, although some wings had other ways of reaching a wreckage).

Courier service and cargo transportation

In the spring of 1942, the Pennsylvania Wing conducted a 30-day experiment with the intention of convincing the AAF that they were capable of flying cargo missions for the nation. The Pennsylvania Wing transported Army cargo as far as Georgia, and top Army officials were impressed. The War Department gave CAP permission to conduct courier and cargo service for the military.

Although not generally remembered as one of CAP's "glamorous" jobs, cargo and courier transportation was an important job for the organization. From 1942 to 1944, the Civil Air Patrol moved around 1,750 short tons (1,600 metric tons) of mail and cargo and hundreds of military passengers.

Pilot training and the cadet program

In October of 1942, CAP planned a program to recruit and train youth with an emphasis on flight training. The CAP cadets assisted with operational tasks and began indoctrination and training towards becoming licensed pilots. Cadets were not exempt from being conscripted; however, the military atmosphere and general setting around them would provide an advantage to cadets who were subsequently called into service. To become a cadet, one had to be between the ages of 15 and 17, and be sponsored by a CAP member of the same gender. The cadet program called for physical fitness, completion of the first two years of high school and satisfactory grades. It was open only to native-born American citizens of parents who had been citizens of the United States for at least ten years. These restrictions were intentionally imposed to hold down membership levels until a solid foundation could be established.

Perhaps the most astonishing fact of the cadet program's 20,000-plus initial membership was the lack of cost; it cost the Office of Civilian Defense less than US$200 to get the program underway, and this was to cover administrative costs.[6]

Other wartime activities

CAP pilots were called on to provide a variety of missions that weren't necessarily combat-related but still of direct benefit to the country. Some of the most notable of these missions were: flying blood bank mercy missions for the American Red Cross and other similar agencies; forest fire patrol and arson reporting; mock raids to test blackout practices and air raid warning systems; supporting war bond drives; and assisting in salvage collection drives. In the Northwestern states, Civil Air Patrol members, armed with shotguns, flew patrols hoping to spot Japanese balloon bombs.

Perhaps the most curious job for CAP was "wolf patrol". In the southwestern United States, the native wolf population had been disrupting ranching operations. One rancher alone lost over 1,000 head of cattle due to wolf predation. This represented a huge monetary loss to ranchers and an added restriction to the already low supply of beef due to wartime rationing. By the winter of 1944, Texas ranchers lobbied the Texan governor to enlist the aid of Civil Air Patrol to control the wolf populations. CAP pilots, armed with firearms, flew over wolf territory and thinned the population to lower levels.

CAP even had its own airbase during the war. A CAA auxiliary landing field, northwest of Baker, California, was given to Civil Air Patrol. Used primarily for training, Silver Lake boasted a hangar, barracks, mess hall and even a swimming pool and bath house.

Results of wartime activities

The Civil Air Patrol's success with the cadet program, along with its impressive wartime record, led the War Department to create a permanent place for it in the department. On April 29, 1943, by order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the command of the Civil Air Patrol was transferred from the Office of Civilian Defense to the War Department and given status as the auxiliary to the Army Air Forces. On March 4, 1943, the War Department issued Memorandum W95-12-43, which assigned the AAF the responsibility for supervising and directing operations of the CAP.

One of the direct outcomes of this transfer was the loaning of 288 Piper L-4 "Grasshopper" aircraft from the AAF to the CAP. These aircraft were used in the cadet recruiting program. By 1945 there was an oversupply of cadets and CAP took over the responsibility of administering cadet mental screening tests.

Postwar

With the close of World War II, CAP suddenly found itself looking for a purpose. It had proved its worthiness and usefulness in wartime, but the ensuing peace had reduced CAP's scope of activities since the AAF assumed a great many of the tasks that the CAP had performed. The very existence of CAP was threatened when the AAF announced that it would withdraw financial support on April 1, 1946, due to massive budget cuts. General "Hap" Arnold called a conference of CAP wing commanders, which convened in January of 1946 and discussed the usefulness and feasibility of a postwar Civil Air Patrol. The conference concluded with the plan to incorporate the Civil Air Patrol.

On March 1 1946, the 48 wing commanders held the first CAP/Congressional dinner honoring President Harry S. Truman, the 79th Congress of the United States, and over 50 AAF generals. The purpose of the dinner was to permit CAP to thank the President and others for the opportunity to serve the country during World War II.

On July 1 1946, Public Law 476 (Pub. L. 79–476), was enacted. The law incorporated the Civil Air Patrol and stated that the purpose of the organization was to be "solely of a benevolent character". In other words, the Civil Air Patrol was to never participate in combat operations again. With the creation of the United States Air Force on July 26 1947, the command of the Civil Air Patrol was transferred from the United States Army to the newly created Air Force. In October of 1947, a CAP board convened to meet with USAF officials and plan the groundwork of the Civil Air Patrol as the USAF auxiliary. After several meetings the USAF was satisfied and a bill was introduced to the United States House of Representatives. On May 26 1948, Public Law 557 (Pub. L. 80–557) was enacted and CAP became the official auxiliary to the United States Air Force.

Missions

The Civil Air Patrol has three key missions: Emergency Services, Aerospace Education and the Cadet Program.

Emergency Services

There are several Emergency Services areas that the Civil Air Patrol covers. The principal categories include Search and Rescue missions, Disaster Relief, Humanitarian Services, and Air Force Support. Others, such as Homeland Security and Counterdrug Operations, are becoming increasingly important.

Search and Rescue Civil Air Patrol is arguably best known for its search activities in conjunction with Search and Rescue (SAR) operations. CAP is involved with approximately 90% of the inland SAR missions directed by the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (AFRCC) at Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida. Outside of the continental United States, CAP directly supports the Joint Rescue Coordination Centers in Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. CAP is credited with saving an average of 100 lives per year.[7]

Disaster relief CAP is particularly active in disaster relief operations, especially in hurricane-prone areas such as Florida, Mississippi and Louisiana. CAP air crews and ground personnel provide transportation for cargo and officials. CAP aircrews often provide aerial imagery to emergency managers in order to help them assess damage. In addition, squadrons and Wings often donate manpower and leadership to local, state and federal disaster relief organizations during times of need. In late 2004, several hurricanes hit the southeastern part of the United States, Florida being the worst damaged. CAP was instrumental in providing help to areas that were hit.[7]

Humanitarian service The Civil Air Patrol conducts Humanitarian Service missions, usually in support of the Red Cross. CAP air crews transport time-sensitive medical materials, such as blood and human tissue, when other means of transportation (such as ambulances) are not practical or possible. Following the September 11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City, all general aviation was grounded. The first plane to fly over the destroyed World Trade Center was a CAP aircraft transporting blood.[7]

Air Force support CAP performs several missions that are not combat-related in support of the United States Air Force. Specifically, this includes damage assessment, transportation of officials, communications support and low-altitude route surveys.[7]

Homeland security As a humanitarian service organization, CAP assists federal, state and local agencies in preparing for and responding to homeland security needs.

Assistance to other agencies The Red Cross, Salvation Army and other civilian agencies frequently ask Civil Air Patrol to transport vital supplies such as medical technicians, medications and other vital supplies. They often rely on CAP to provide airlift and communications for their disaster relief operations. CAP also assists the United States Coast Guard and United States Coast Guard Auxiliary.

Aerospace Education program

Civil Air Patrol's Aerospace Education Program serves the CAP cadet and senior member population as well as the general public. Education for members includes formal, graded courses about all aspects of aviation, including flight physics, dynamics, history, application and others. Courses cover the space program as well as new technologies that make advances in aviation and space exploration possible. There are several programs for CAP pilots to improve their flying skills and earn FAA ratings.

Through outreach programs, CAP helps school teachers integrate aviation and aerospace into the classroom, providing seminars, course materials and sponsorship of the National Congress on Aviation and Space Education. CAP members also provide their communities with resources for better management of airports and other aviation-related facilities and promote the benefits of such facilities.

Aerospace education for cadets The CAP Cadet Program has a mandatory aerospace education program; in order to progress, a cadet must take courses and tests relating to aviation. Cadets also have educational opportunities through guest speakers, model building and actual flight.

Aerospace education for senior members Senior members of the CAP may study aerospace through the Senior Member Professional Development Program. CAP encourages its senior members to learn about aviation and its history, although this is not mandatory. Those who complete the Aerospace Education Program for Senior Members may earn the Charles E. "Chuck" Yeager Aerospace Education Award.

Aerospace education for non-members The purpose of the External Aerospace Education program, defined in CAP's 1946 congressional charter, is to "encourage and foster civil aviation in local communities". CAP has focused on providing schools and teachers with materials and help for educating youth about aerospace. CAP members visit schools, host field trips, science competitions and fairs, and participate in other related activities. In addition to schools, CAP reaches out to other organizations, such as the Boy Scouts of America, the Girl Scouts of the USA and 4-H.[8]

Cadet program

Concept

Civil Air Patrol's cadet program is a traditional military-style cadet program. CAP cadets wear modified versions of Air Force uniforms, hold rank and grade, and practice military customs and courtesies. They are also required to maintain physical fitness standards and are tested on their fitness and their knowledge of leadership and aerospace subjects for each promotion. This program is similar to that of the Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) primarily because the Air Force JROTC program was 'cloned' from the CAP Cadet Program in the 1960s. However, there are several key differences between the two programs.

The current CAP Cadet Program was designed by John V. "Jack" Sorenson who held the position of Civil Air Patrol's Director of Aerospace Education in the 1960s. This program is composed of four phases (Learning, Leadership, Command, and Executive) each of which is divided into several achievements. Achievements generally correspond to grade promotions while phases are tied to levels of responsibility. The Cadet Program operates at a local unit (squadron) level with weekly meetings and weekend activities but also has national and wing-sponsored events, including week-long and multi-week summer activities, of which encampments are an example.

One of the features of the CAP Cadet Program is that as Cadets progress, they are given additional responsibility for scheduling, teaching, guiding and commanding the other cadets in their units. They also assist their Senior Staffs in executing the Cadet Program. It is not unusual for a Cadet officer to command an encampment of hundreds of junior Cadets.[citation needed] This, coupled with the fact that Cadets may also participate in CAP Emergency Services missions, sets CAP's Cadet Program even further apart from other cadet programs.

In CAP, cadets are given ample opportunity to lead and to follow. They not only hold leadership positions at squadron and wing activities, they also are often involved in planning these activities. Cadets may complete paperwork, command other cadets, and teach at weekly meetings and weekend and summer events. When someone says something about the Cadet Program, they are talking about what the cadets do, not what the senior members tell them to do.[9]

Organization

The Cadet Program is overseen and administered by senior members who generally specialize in the Cadet Program. At the squadron level, the Cadet Commander's chain of command passes through the Deputy Commander for Cadets before reaching the squadron commander. There are 'Director of Cadet Programs' positions at all command levels above squadron. In addition to the Deputy Commander for Cadets, squadrons also have a Leadership Officer, a Senior Member whose job is to see to the military aspects of the Cadet program, such as uniforms, customs and courtesies.

Cadets have a grade structure similar to the United States Air Force enlisted and officer ranks (excluding those of general officers). A Cadet starts as a Cadet Airman basic and then is promoted as he or she completes each achievement. To complete an achievement, a cadet must pass a physical fitness test as well as two written tests, one for leadership and one for aerospace education. The only exceptions to this rule are the promotion to Cadet Airman and Cadet Staff Sergeant which have no aerospace test. For some achievements, an additional test of drill proficiency is required. The achievements and their corresponding grades are listed in the table; the C/ prior to each grade is read as 'Cadet', so C/AB is read as "Cadet Airman Basic".

The milestones in Civil Air Patrol's Cadet Program are the Major General John F. Curry Award, Wright Brothers Award, the General Billy Mitchell Award, the Amelia Earhart Award, then General Ira C. Eaker Award and the General Carl A. Spaatz Award. As of mid-2005 fewer than 1600 Spaatz Awards have been earned since the first was awarded to Cadet Douglas Roach in 1964. Cadet Roach went on to an Air Force career and later was a pilot on the USAF Thunderbirds aerial demonstration team.

Each milestone award in Civil Air Patrol confers upon a cadet various benefits. Upon earning the Mitchell Award and the grade of Cadet Second Lieutenant, a cadet will automatically be given the rank of Airman First Class (E-3) upon enlisting in the United States Air Force or (E-2) upon enlisting in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps, though the rank may only be worn after successfully completing Basic Training. Along with being awarded the Earhart Award and being promoted to C/Capt a cadet may attend International Air Cadet Exchange.

According to the CAP National website, the percentages for cadets receiving the milestone awards are as follows:

- Mitchell 12%

- Earhart 5%

- Eaker 2%

- Spaatz 0.05%

Cadets that transfer to the Senior Member side between his or her 18th birthday and 21st birthday receive the rank of Flight Officer (if the highest cadet award earned was the Mitchell), Technical Flight Officer (if the highest cadet award earned was the Earhart) or Senior Flight Officer (if the highest cadet award earned was the Spaatz). If a cadet decides to transfer to the senior side after his or her 21st birthday, they are eligible for the rank of 2d Lt (if the highest cadet award was the Mitchell), 1st Lt (if the highest cadet award was the Earhart), or Capt (if the highest cadet award was the Spaatz).

Activities

- The following are local activities common throughout the Civil Air Patrol program.

Orientation flights

- Cadets under the age of 18 are eligible for ten orientation flights in CAP aircraft including five glider and airplane flights. Cadets over 18 years of age can still participate in military orientation flights. Some CAP wings have flight academies where cadets can learn to fly. The USAF and Army also frequently schedule orientation flights for CAP cadets in transport aircraft such as the KC-10 Extender, C-130 Hercules and the C-17 Globemaster III or, in the case of the Army, UH-60 Black Hawk and CH-47 Chinook helicopters.

Encampment

- Encampment is typically is a ten day- 3 weeks basic training for Cadets. While curriculum varies from wing to wing it usually consists of physical training, class on leadership and aerospace as well as possible Emergency Service, survival skills, First Aid, rappelling, and marksmanship training.

Region Cadet Leadership Schools

- The Region Cadet Leadership Schools (RCLS) provide training to increase knowledge, skills, and attitudes as they pertain to leadership and management. To be eligible to attend, cadets must be serving in, or preparing to enter, cadet leadership positions within their squadron. RCLS’s are conducted at region level, or at wing level with region approval.

Non-Commissioned Officer Schools/Academies

- Held in many wings, Cadet NCO Schools are designed to teach basic leadership principles to cadet leaders during their earlier positions in the Cadet Program.

Cadets and the military

CAP members do not incur any military obligation. However, the U.S. Congress stated in the Recruiting, Retention, and Reservist Promotion Act of 2000 that CAP and similar programs "provide significant benefits for the Armed Forces, including significant public relations benefits."[10] CAP cadets who go on to join the Air Force can enter as an Airman First Class (E-3) if they have earned the Mitchell Award. Most cadets choose not to go on to military careers; among those that do, many choose branches of service other than the Air Force. CAP cadets that do enter the military perform statistically better during recruit training and at the various service academies than their peers without CAP cadet experience.

Scores of former CAP cadets have gone on to become military leaders, many achieving notability, including: Lt Shane Osborne, pilot of the United States Navy EP-3E Aries II aircraft which collided with a Chinese fighter in April 2001; Capt Scott O'Grady, whose F-16 was shot down over Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995; Lt Col Eric A. Boe, NASA pilot and Director of Operations, Russia; Commander William Oefelein, NASA astronaut and STS-116 pilot; and General Michael E. Ryan, former Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. Major Nicole Malachowski, a former CAP cadet from Las Vegas, Nevada, had become the first woman pilot to join the USAF Thunderbirds aerial demonstration team, serving as #3 on the team from 2006 through 2007. Other notable former cadets include Jack Sarfatti, a theoretical physicist, and Kevin 'Kojak' Davis, a United States Navy Blue Angels pilot.[11] Some former cadets became more infamous than famous, including Lee Harvey Oswald, David Ferrie, Barry Seal, and James R. Bath, as well as David Graham and Diane Zamora, of the "Texas Cadet Murder" case, which later became a made-for-TV movie.[12][13]

Cadet Oath

Cadets ascribe to the following oath during their membership:

"I pledge that I will serve faithfully in the Civil Air Patrol Cadet Program,

and that I will attend meetings regularly, participate actively in unit activities, obey my officers, wear my uniform properly, and advance my education and training rapidly to prepare myself to be of service to my community, state, and nation.

Cadet Honor Code

Civil Air Patrol cadets adhereto the following honor code.

"On my honor as a Civil Air Patrol Cadet I will not lie, cheat, or steal. Nor Tolerate those who do."

Cadet Motto

The Civil Air Patrol has two mottos they are.

"Semper Vigilance" Latin for "Alway Vigilant"

"Where Imagintaion Takes Flight"

Equipment

The Civil Air Patrol operates fixed-wing aircraft, training gliders, ground vehicles and a national radio communications network.

Aircraft

The Civil Air Patrol owns and operates the world's largest fleet of single-engine aircraft, predominantly Cessna 172 Skyhawk and Cessna 182 Skylane aircraft.

In 2003, the unique Australian designed and built 8 seat Gippsland GA8 Airvan was added to the corporate fleet, making CAP the first American organization to own and operate this aircraft, and the largest fleet owner of the GA8 Airvan world wide. These aircraft carry the Airborne Real-time Cueing Hyperspectral Enhanced Reconnaissance (ARCHER) system, which can be used to search for aircraft wreckage based on its spectral signature.

Other aircraft types include the Cessna 206 and the Maule MT-235. Some members use their own airplanes for CAP missions. CAP also has several dozen gliders, such as the L-23 Super-Blanik, the Schleicher ASK 21 and the Schweizer SGS 2-33, used mainly for cadet orientation flights.

In addition to CAP's fleet of more than 530 aircraft, over 4,000 member-owned aircraft are made available for official tasking by CAP's volunteers should the need arise. Aircraft on search missions are generally manned by a crew of three: A Mission Pilot, responsible for the safe flying of the aircraft; a Mission Observer, responsible for Navigation, Communications and coordination of the mission (as well as actually looking out the window); and a Mission Scanner who is responsible for looking out the window for crash sites and damage clues. Additionally, the Mission Scanner may double as an SDIS operator. Larger aircraft may have additional Scanners aboard, providing greater visual coverage. Because of the additional ARCHER equipment, the crew of a Civil Air Patrol GA8 Airvan may also include an operator of the ARCHER system, depending upon the requirements of the mission.

Ground vehicles

CAP owns roughly 1,000 vehicles (mostly vans for carrying personnel) and assigns them to units for use in the organization's missions. Members who use their own vehicles are reimbursed for fuel, oil and communications costs during a USAF-assigned emergency services mission.

Communication

CAP operates a national radio network of HF (SSB) and VHF (FM) radios, repeaters. All previous on-the-air data transfer modes are no longer available to Civil Air Patrol as it's communicaitons directorate has made no effort to ensure that it is incorporated in current frequency assignments of equipment resources.

Radio communications are now facilitated under NTIA specifications, which Civil Air Patrol directorates have misapplied to more stringent standards. CAP's radio network is designed for use during a national or regional emergency when existing telephone and Internet communications infrastructure is not available, however current internal policies have emaciated the program.

Outside of such emergencies, most of CAP's internal communications are conducted on the Internet. CAP frequencies are designated by the Department of Defense as Unclassified - For Official Use Only information.

Other

Some aircraft in the CAP Fleet are equipped with the Satellite Digital Imaging System (SDIS). This system allows CAP to send back real-time images of a disaster or crash site to anyone with an e-mail address, allowing the mission coordinators to make better decisions.

The Airborne Real-time Cueing Hyperspectral Enhanced Reconnaissance (ARCHER) imaging system, mounted aboard the GA8 Airvan uses visible and near-infrared light to examine the surface of the Earth and find suspected crash sites or evaluate areas affected by disasters.

The ARCHER system is capable of detecting various colors in the spectrum of light. When the system is looking for a target the operators provide a spectral fingerprint of the object they are looking for. A snapshot is taken and a flag is created for the operator to go back and look at each time ARCHER finds an object that matches the spectral signature for which they are looking. The ARCHER system can also be set up to look for abnormalities in the surrounding area. For example, if you are flying over trees, the main color is green and green variants and the system sees this. If it spots a yellow in a bunch of green it will also flag that area as a possible moving target.

Both the SDIS and ARCHER systems were used to great success in the response to Hurricane Katrina.

A hand-held radio direction finder, the "L-Per", is used by ground teams to search for downed aircraft. The ground teams carry equipment on their person that they use while in the field. This equipment includes flashlights, signal mirrors, tactical vests, safety vests, and food that will last them at least 24 hours.

Membership

CAP has some 57,000 Officer and Cadet members in over 1,600 local units across the United States (including Alaska and Hawaii), in Puerto Rico and at overseas Air Force installations. CAP members are civilians and are not paid by the U.S. government for their CAP service. Rather, members are responsible for paying annual dues for membership, and pay for their own uniforms and other related expenses.[14]

Officer membership is open to all U.S. Citizens and resident aliens aged 18 and over who are able to pass an FBI background check. There is no upper age limit, nor membership restrictions for physical disabilities, due to the number of different tasks which members may be called on to perform. Cadet membership is open to those between 12 and 18 (a cadet may remain in the Cadet Program until he/she is 21) years of age who maintain satisfactory progress in school. (See [1] for CAP membership information.)

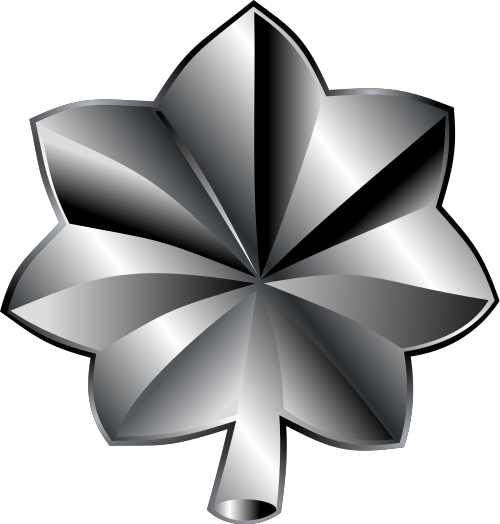

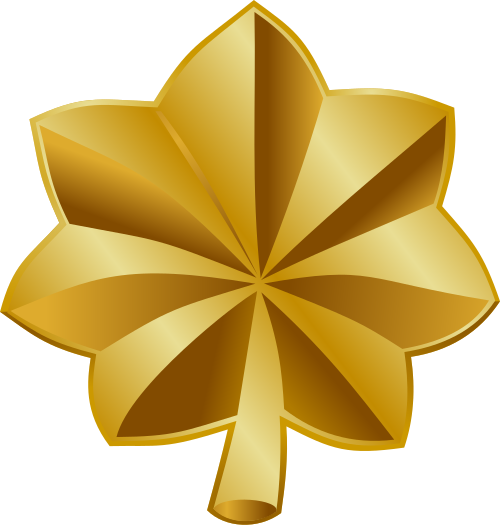

Officers

| Grade | Insignia |

| Major General Maj Gen |

|

| Brigadier General Brig Gen |

|

| Colonel Col |

|

| Lieutenant Colonel Lt Col |

|

| Major Maj |

|

| Captain Capt |

|

| First Lieutenant 1st Lt |

|

| Second Lieutenant 2d Lt |

|

| Senior Flight Officer SFO |

|

| Technical Flight Officer TFO |

|

| Flight Officer FO |

|

| Senior Member SM |

Officers are those who are over 21 years old, or who joined CAP for the first time past the age of 18. Officers who have not yet turned twenty-one years are eligible for Flight Officer ranks, which include Flight Officer (FO), Technical Flight Officer (TFO), and Senior Flight Officer (SFO). There is no retirement age for CAP members, and there are no physical requirements for joining. The only physical requirements an Officer must follow are the grooming and weight standards required of members who wear the USAF-style uniforms (these do not apply to members who choose to wear the CAP-distinctive uniforms).

Grades up to lieutenant colonel reflect progression in training and organizational seniority, rather than command authority. Because of this, it is not uncommon for CAP officers commanding groups and squadrons to have members of superior grades serving under them. U.S. military officers (current, retired and former) may be promoted directly to the CAP grade equivalent to their military grade through Lieutenant Colonel. Current retired and former enlisted members of any branch of the US military may elect to hold the Air Force equivalent of that grade (enlisted ranks not shown above) in CAP, or be appointed to CAP Officer rank based on the same standards as non-prior service members.

Except for a few exceptional cases, CAP officers are only promoted to the grade of CAP Colonel upon appointment as wing (state-level) commander. Wing Commanders who successfully complete their tour of duty as Wing Commander retain the grade of Colonel. Region (geographic groups of wings) commanders are graduated Wing Commanders and hold the rank of CAP Colonels. Since 2003, National Vice Commanders have been promoted to Brigidier General upon their election to that office. Prior to Dec 2002, CAP National Commanders were appointed to the grade of Brigidier General. Since then, CAP National Commanders have been appointed to the grade of CAP Major Generals upon their election as National Commander.

Officer Professional Development Program

Officers are provided with an optional professional development program and are encouraged to progress within it. Progression in the training program is required for promotion of those officers who are not using their current or former military grades within CAP, or those with certain professional appointments (such as legal or medical).

The Officer Program consists of five levels, and each has components of leadership training, corporate familiarization and aerospace education, as well as professional development within chosen "Specialty Tracks." There are many Specialty Tracks and they are designed both to support the organization and to provide opportunities for officers to take advantage of skills they have from their private lives. Available Specialty Tracks include Logistics, Communications, Cadet Programs, Public Affairs, Legal, Administration, Emergency Services and Finance, and many more.

Cadet members

Relationship to the military

CAP members are not subject to the UCMJ and therefore do not have command or other authority over members of the United States military. Similarly, military officers have no command authority over CAP members. As part of recognition of CAP's service to the USAF, however, CAP Officers (Senior Members) in the grade of second lieutenant and above are allowed to wear "U.S." as part of their uniform. All CAP members are required to render military courtesies to all members of the U.S. military and those of friendly foreign nations.

Uniforms

Historically, CAP members have worn slight variations of the uniforms worn by their military sponsor, and current CAP uniforms are US Air Force uniforms with different insignia. Because of the similarity in the uniforms, CAP members are sometimes mistaken by the public for Air Force officers.

In order to wear the Air Force-style uniform, CAP members must meet appearance standards (having to do with height/weight ratio, length of hair, and beards). These "grooming standards" are a less rigorous version of those used by the Air Force.

Since some CAP members do not meet the standards for the Air Force-style uniform, CAP developed a range of "corporate" (or "CAP distinctive") uniforms in the 1970s for wear by senior members. These uniforms are an option available to all senior members, but are the only uniforms available to those who do not meet grooming standards.

Senior Members are obligated to wear uniforms only when flying, when working with Cadets, or when participating in Emergency Services activities.

There are over ten uniform combinations. The basic ones worn by most members are:

- Air Force-style uniforms:

- Service Dress Uniform - the Air Force blue uniform, consisting of dark blue trousers, light blue shirt, and dark blue jacket and tie.

- Service Uniform - same as the service dress uniform, except without the dark blue jacket. The tie is optional with the short sleeve version.

- Battle Dress Uniform (BDU)—the standard Air Force "woodland camouflage" field uniform, with blue CAP insignia.

- Flight Uniform - the standard green NOMEX one-piece flight suit worn by Air Force flight crews, but with CAP insignia. This is worn by flight crews only.

- Mess Dress Uniform - the dark blue Air Force mess dress uniform with CAP-distinctive insignia and sleeve braid. This is worn by senior members only.

- Corporate ("CAP distinctive") uniforms:

- Field Uniform - a dark blue version of the battle dress uniform

- Aviator Shirt Uniform - an aviator white shirt with epaulettes, worn with gray shoulder marks and gray trousers.

- Flight Uniform - A dark blue version of the one-piece flight suit. This is worn by flight crews only.

- Utility Uniform - A dark blue one-piece uniform similar to, but distinct from, the Flight Uniform. Worn for similar duty to the Field Uniform.

- Blazer Uniform - A dark blue jacket worn with a white shirt, gray trousers, and a CAP or Air Force tie.

- Golf Shirt Uniform - A dark blue short-sleeve golf shirt with the CAP seal screened or embroidered on the chest. This is worn with gray trousers.

Insignia

Initially, CAP officers wore metal grade insignia and red epaulets and CAP distinctive insignia on Army Air Force uniforms. The red epaulets went out with the adoption of the U.S. Air Force uniforms after World War II. Until 1990, CAP uniforms were generally USAF uniforms and rank insignia with the addition of the lettering "CAP" and distinctive nametags.

In 1990, the metal grade insignia worn by CAP senior members on the Air Force-style uniform was replaced with maroon shoulder marks with the member's embroidered grade insignia. In 1995, CAP shoulder marks were changed from maroon to gray. In 1996, the Air Force authorized CAP officers to wear the same "U.S." collar insignia as Air Force personnel. Senior members without grade and cadets still wear "C.A.P." collar insignia. Senior members did not wear metal grade insignia on the shoulders again until a double-breasted blue "service dress-style uniform" was added to the list of "CAP distinctive uniforms" in 2006.

Promotions

Officers can become eligible for promotion to officer grades. After joining, an officer must complete Level I, which requires completion of the CAP Foundations Course, Cadet Protection Program Training (CPPT) and Operations Security (OPSEC) Awareness Training. Upon completion of this training they are awarded the CAP Membership Award Ribbon and are eligible for promotion to Second Lieutenant after six months. New members over 18 but not yet 21 years old are appointed to Flight Officer grades.

After completing the Technician level of a specialty track and one year as a Second Lieutenant, officers are eligible for promotion to First Lieutenant and receive the Leadership Award Ribbon. With the added completion of Squadron Leadership School and the CAP Senior Officer Course, officers will receive the Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. Award for completion of Level II. After 18 months as a First Lieutenant, officers are eligible for promotion to Captain.

With additional management training and at least three years as a Captain, officers may receive the Grover Loening Award for completion of Level III. This achievement makes them eligible for promotion to Major. Officers who have completed Level IV training earn the Paul E. Garber Award. Four years as a Major and completion of Level IV makes an officer eligible for promotion to Lieutenant Colonel. Completion of Level V, which requires more management training and teaching experience, earns the Gill Robb Wilson Award.

Administration

Organization

Civil Air Patrol is organized along a military model, with lower levels of command reporting to higher levels. The CAP is not, however, a branch of the United States Armed Forces even though it is the official Air Force Auxiliary when performing Air Force missions, nor are CAP members deployed into combat situations. The CAP does not have jurisdiction or command over any active duty, National Guard, or Reserve U.S. forces.

There are seven distinct echelons (levels of command) in CAP, although not all are used at all times.

The organization is governed by a Board of Governors established by federal law in 2001. The board consists of 11 members: four Civil Air Patrol members (currently the National Commander, National Vice Commander, and two members-at-large appointed by the CAP National Executive Committee), four Air Force representatives appointed by the Secretary of the Air Force, and three members from the aviation community jointly appointed by the CAP National Commander and the Secretary of the Air Force. The Board of Governors generally meets two to four times annually and operates primarily at the "macro" level, providing strategic vision and guidance to the volunteer leadership and corporate staff.

The volunteer leadership consists of the National Commander and his staff. This staff consists of a Vice Commander, Chief of Staff, National Legal Officer, National Comptroller, the Chief of the CAP Chaplain Service, and the CAP Inspector General. The National Commander holds the grade of CAP Major General, the National Vice Commander holds the grade of CAP Brigadier General, and the rest of the National Commander's staff hold the grade of CAP Colonel.

CAP National Headquarters is located at Maxwell Air Force Base outside Montgomery, Alabama. The headquarters employs a professional staff of over 100 and is led by the CAP Executive Director (analogous to a corporate Chief Operating Officer), who reports to the Board of Governors. The National Headquarters staff provides program management for the organization and membership support for the 1,700+ volunteer field units across the country.

Below the National Headquarters level there are eight geographic Regions and a handful of overseas squadrons at various military installations worldwide. Regions, commanded by a CAP Colonel, are comprised of several states (or 'Wings', in CAP parlance). The eight regions are Northeast, Middle East, Southeast, Great Lakes, Southwest, North Central, Rocky Mountain and Pacific.

Each of the fifty states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia are designated a CAP "Wing", each with a commander who is a CAP Colonel and the sole corporate officer for each state. Each wing commander oversees a wing headquarters staff comprised of experienced volunteer members.

Larger Wings may have an optional subordinate echelon of "Group," at the discretion of the Wing Commander. Groups are comprised of at least five squadrons or flights. They are generally commanded by a member holding the grade of Major or Lieutenant Colonel.

Local units are called squadrons or flights. Local communities may be served by one or more squadrons, or by a flight, as smaller units are known. Squadrons are the true heart of the Civil Air Patrol, and it is at the squadron level where most of the missions of the organization are accomplished. Active members are assigned to a squadron (excepting the few assigned to higher echelons of command) and will generally attend a meeting every week. There will also be occasional weekend training activities. Squadrons will often work cooperatively on training activities and there is a great deal of coordination between squadron commanders. Squadrons are generally commanded by a CAP Captain or Major, but exceptions are common.

Civil Air Patrol squadrons are designated as either cadet, senior, or composite squadrons. A CAP composite squadron is comprised of both cadets and senior members, who may be involved in any of the three missions of the Civil Air Patrol. Composite squadrons have two deputy commanders to assist the squadron commander: a Deputy Commander for Seniors and a Deputy Commander for Cadets. A senior squadron is comprised only of senior members, who participate in the emergency services or aerospace education missions of CAP. Finally, a cadet squadron is comprised largely of cadets, with a small number of senior members as necessary for supervision of cadets and the proper execution of cadet programs.

A CAP Flight is a semi-independent unit that is used mainly as a stepping-stone for a new unit until they are large enough to be designated a Squadron. There are very few flights in Civil Air Patrol, due to their usual temporary nature. A flight will be assigned to a squadron, and it is the job of the flight and squadron commander to work together to build the flight into a full squadron.

Overseas squadrons operate independently of this structure, reporting directly to the National Headquarters. Commanders of overseas units must be an active duty Air Force non-commissioned or commissioned officer holding the rank of E-6 (Technical Sergeant) or above in addition to being a Civil Air Patrol member.

The current National Commander of the Civil Air Patrol is Brigadier General Amy Courter, CAP, who took over from Major General Antonio J. Pineda, CAP. On August 7, 2007, the membership of Gen. Pineda was suspended by the Civil Air Patrol Board of Governors pending an internal investigation of allegations that Pineda had subordinate officers take USAF Air Command and Staff College exams for him. Gen. Courter was named Acting National Commander for the duration of the suspension.[15] The Board of Governors officially removed Gen. Pineda from the position of National Commander on October 2, 2007, promoting Gen. Courter to Interim National Commander until the Board meets again in August 2008, at which time a new National Commander will be elected. These events have placed Gen. Courter, formerly the first female National Vice Commander, as the first female National Commander.[16]

Funding

The Civil Air Patrol is a non-profit corporation established by Public Law 476. It receives its funding from four major sources: membership dues, corporate donations, Congressional appropriations, and private donations.

Today, apart from member dues, Civil Air Patrol receives funding from donations and grants from individuals, foundations and corporations; from grants and payments from state governments for patrolling and other tasks as agreed by Memorandums of Understanding; and from federal funding for reimbursement of fuel, oil and maintenance plus capital expenses for aircraft, vehicles and communications equipment.

There are very few paid positions in Civil Air Patrol. Most are located at National Headquarters, but a few wings have paid administrators or accountants.

Relationship between CAP and the Air Force

Although CAP retains the title "United States Air Force Auxiliary", this Auxiliary status is only applicable when CAP members and resources are on an Air Force-assigned mission with an Air Force-assigned mission number. At all other times, such as aid to civilian authorities, the CAP remains a private, non-profit corporation.

Changes for a new century

The USAF's Air Education and Training Command, through the Air University, has been the parent command of CAP. In October 2002, the USAF announced plans to move CAP into a new office for homeland security. Currently remaining under the AETC, CAP now has a Memorandum of Understanding with 1st Air Force. In addition, CAP's national commander was promoted to the grade of Major General from Brigadier General, reflecting the increased role of Civil Air Patrol in the post 9-11 era.

In March 2006, optional new "corporate" uniforms were introduced for senior members with white shirts, Air Force blue trousers and Air Force officer epaulettes without the "CAP" titling. Notably, this uniform has a nameplate that only says "Civil Air Patrol" with the member's last name; there is no mention of "United States Air Force Auxiliary." At the 2006 National Executive Committee meeting, a matching double-breasted blue service coat was approved. Metal rank insignia and "CAP" collar insignia are worn on this, along with the metal nameplate and CAP buttons, but only CAP ribbons and devices are permitted; prior-service military ribbons and devices are not be authorized for wear on this uniform (unless authorized to be worn on civilian clothing by the awarding authority). The service and flight caps will continue to be worn with CAP-distinctive variations.

Media

Books

- Burnham, Frank A (1974). Hero Next Door: Story of the Civilian Volunteers of the Civil Air Patrol. Aero Publishers. ISBN 0816864500.

- Neprud, Robert E (1948). Flying Minute Men: The Story of the Civil Air Patrol. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. ASIN B0007DMEWM.

- Stanley, John B (1954). Squadron Alert! A Civil Air Patrol Adventure Story. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. ASIN B0007E408C.

Television and movies

- During the search for Fallon Carrington on ABC's Dynasty, the Civil Air Patrol was portrayed as the lead organization in the search. The episode featured actual CAP members.

- In the movie Red Zone Cuba, which was spoofed by Mystery Science Theater 3000, one of the scenes featured a large radio van in the background with Civil Air Patrol markings on it.

- One of the ABC's Weekend Specials in 1981 was an adaptation of the book Mayday! Mayday! by Hilary Martin wherein the Civil Air Patrol was used to locate passengers of a private airplane crash.

- According Oliver Stone's film JFK, David Ferrie and other members of the alleged conspiracy to assassinate President John F. Kennedy were members of the Civil Air Patrol, and had supposedly given Cuban exiles military training for the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Radio and podcast

- "Civil Air Patrol Today" premiered in April 2005 as a radio program produced by members of the Maryland Wing. In September of 2005, the show debuted as a podcast on the newly redesigned Maryland Wing web site.

Other

- The Sony PlayStation game "Syphon Filter 2" places a group of the game's antagonists at an 'abandoned Civil Air Patrol base' in the Colorado Rockies.

- The new Microsoft Flight Simulator X includes the Maule Orion with Civil Air Patrol paint scheme and a search mission in this aircraft.

- In The 2004 PlayStation 2 game "Medal of Honor: European Assault", several period recruiting posters for Civil Air Patrol are noted in the background in various levels of the game.

See also

- Awards and decorations of the Civil Air Patrol

- Cadet grades and insignia of the Civil Air Patrol

- National cadet activities of the Civil Air Patrol

- United States Air Force

- United States Coast Guard Auxiliary

- Satellite Digital Imaging System

- Explorer Search and Rescue

- Cessna 172

- Cessna 182

- Search and Rescue

References

- ^ CAP Pamphlet 50-5, page 7, "Early Days and Wartime Activities", paragraph 4–6

- ^ CAPP 50-5, page 8, "Coastal Patrol Authorized", paragraph 1

- ^ CAPP 50-5, page 10, "Coastal Patrol Authorized", paragraph 4

- ^ http://www.cap.gov/index.cfm?fuseaction=display&nodeID=6192&newsID=2276&year=2006&month=8 CAP News Online.

- ^ CAPP 50-5, page 13, "Target Towing and Other Missions", paragraph 7

- ^ Introduction to Civil Air Patrol (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: National Headquarters Civil Air Patrol. 2002-08-01. pp. p. 14. CAPP 50-5. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

Surprisingly, recruiting 20,000-plus CAP cadets only cost the Office of Civilian Defense slightly less than $200, spent solely on administrative costs.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d "Emergency Services". Civil Air Patrol. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ^ "Aerospace Education". Civil Air Patrol. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ^ "Cadets". Civil Air Patrol. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ^ 106th Congress, 2D Session (2000-04-06). Recruiting, Retention, and Reservist Promotion Act of 2000 (H.R. 4208). U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved on 2007-10-18

- ^ Last, Jonathan V (2007-05-11). "Quiet Hero". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Texas v. Diane Zamora". Court TV Online. 1999. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Love's Deadly Triangle: The Texas Cadet Murder at IMDb

- ^ Baker, Dean (2007-12-27). "Civil Air Patrol aims to serve, save lives". The Columbian via The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "U.S. Civil Air Patrol's Board of Governors suspends CAP national commander". CAP News Online. 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "U.S. CAP Board of Governors removes national commander". CAP News Online. 2007-10-03. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Civil Air Patrol. CAPP 50-5.

- Civil Air Patrol. CAPR 52-16.

- Civil Air Patrol. Leadership for the 21st Century, Volume One.

- Civil Air Patrol (2005). Retrieved April 21, 2005.

- 102nd Composite Squadron, Rhode Island Wing, Civil Air Patrol (2005). Squadron site Retrieved April 21, 2005.

- The Spaatz Association (2005). Spaatz.org Retrieved April 25, 2005.

External links

- Civil Air Patrol - Official web site

- National Museum of the Civil Air Patrol - CAP Historical Foundation

- Spaatz Association

- Civil Air Patrol profile at GlobalSecurity.org