8½: Difference between revisions

→External links: promotional link rmv: danger of turning section into a link farm |

|||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

* {{amg movie|id=1:318|title=8½}}. |

* {{amg movie|id=1:318|title=8½}}. |

||

*[http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20000528/REVIEWS08/5280301/1023 Review by Roger Ebert] |

*[http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20000528/REVIEWS08/5280301/1023 Review by Roger Ebert] |

||

*[http://www.noripcord.com/reviews/film/8½ Essay on 8½'s influences on ''Stardust Memories''] |

|||

{{start box}} |

{{start box}} |

||

{{s-ach}} |

{{s-ach}} |

||

Revision as of 00:05, 16 December 2008

| 8½ | |

|---|---|

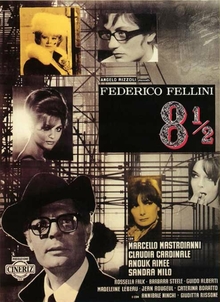

Original theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Federico Fellini |

| Written by | Ennio Flaiano Tullio Pinelli Federico Fellini Brunello Rondi |

| Produced by | Angelo Rizzoli |

| Starring | Marcello Mastroianni Claudia Cardinale Anouk Aimée Sandra Milo |

| Cinematography | Gianni Di Venanzo |

| Edited by | Leo Cattozzo |

| Music by | Nino Rota |

Release dates | February 14, 1963 (Italy) June 25, 1963 (US) |

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

8½ (pronounced Otto e mezzo in Italian) is a 1963 film directed by Italian director Federico Fellini. Co-scripted by Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano, and Brunello Rondi, it stars Marcello Mastroianni as Guido Anselmi, a famous Italian film director.

Shot in black-and-white by influential and innovative cinematographer Gianni di Venanzo, the film features a soundtrack by Nino Rota with costume and set designs by Piero Gherardi.

The movie's title refers to the total number of films Fellini had previously directed. These included six features, two short segments, and a collaboration with another director, Alberto Lattuada. The latter three productions accounted for a "half" film each. [1]

8½ won two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design (black-and-white). Acknowledged as a highly influential classic [2], it was ranked 3rd best film of all time in a 2007 poll of film directors conducted by the British Film Institute. [3]

Plot

The plot revolves around an Italian film director, Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), who is suffering from "director's block." He is supposed to be directing an ill-defined film that is hinted at as being science fiction as well as possibly autobiographical, but has lost interest amid artistic and marital difficulties. As Guido struggles half-heartedly to work on the film, a series of flashbacks and dreams delve into his memories and fantasies; they are frequently interwoven with reality.

Cast

- Marcello Mastroianni as Guido Anselmi

- Claudia Cardinale as Claudia

- Anouk Aimée as Luisa Anselmi

- Sandra Milo as Carla

- Rossella Falk as Rossella

- Barbara Steele as Gloria Morin

- Madeleine LeBeau as Madeleine

- Caterina Boratto as La signora misteriosa

- Eddra Gale as La Saraghina

- Guido Alberti as Pace

- Mario Conocchia as Conocchia

- Bruno Agostini as Il segretario di produzione

- Cesarino Miceli Picardi as Cesarino

- Jean Rougeul as Carini

- Mario Pisu as Mario Mezzabotta

Themes

8½ is about the struggles involved in the creative process, both technical and personal, and the problems artists face when expected to deliver something personal and profound with intense public scrutiny, on a constricted schedule, while simultaneously having to deal with their own personal relationships. It is, in a larger sense, about finding true personal happiness in a difficult, fragmented life. Like several Italian films of the period (most evident in the films of Fellini's contemporary, Michelangelo Antonioni), 8½ also is about the alienating effects of modernization.[4]

8½ is highly autobiographical: Fellini made the film because he himself was suffering from director's block; the character of Guido (played by Mastroianni, whom Fellini often used to mirror himself in his films) is a representation of himself and many of Guido's memories are based on Fellini's own. Because of this, 8½ is a recursive film: a film about the creation of itself as well as a metafilm.

The title is in keeping with Fellini's self-reflexive theme - the making of his eighth-and-a-half film. [5] His previous six feature films included Lo sceicco bianco (1952), I vitelloni (1953), La strada in (1954), Il bidone (1955), Le notti di Cabiria (1957), and La dolce vita (1960). With Alberto Lattuada, he co-directed Luci del varietà (Variety Lights) in 1950. His two short segments included Un Agenzia Matrimoniale (A Marriage Agency) in the 1953 omnibus film L'amore in città (Love in the City) and Le Tentazioni del Dottor Antonio from the 1962 omnibus film Boccaccio '70.

The working title for 8½ was La bella confusione (The Beautiful Confusion) proposed by co-screenwriter, Ennio Flaiano, but Fellini then "had the simpler idea (which proved entirely wrong) to call it Comedy." [6]

Fellini did not originally intend the film to be so obviously autobiographical. According to screenwriter Tullio Pinelli, in the original script, Guido was a writer who could not finish his novel. However, when Fellini found out that Marcello Mastroianni had just played a writer in Michelangelo Antonioni’s La notte, he changed the character into a movie director, explaining, "How am I going to ask Marcello to play a writer again? He’ll end up believing he’s one and he’ll write a novel." [citation needed] Four years after completing 8½, life imitated art. Fellini's producer, Dino De Laurentiis, had invested in an expensive replica of Cologne Cathedral and other huge sets that had been built in Cinecittà for Fellini's film Il viaggio di G. Mastorna. Fellini then informed De Laurentiis that he would not finish the film. De Laurentiis was furious, much like the producer in 8½. [citation needed]

Production

When shooting began on 9 May 1962, Eugene Walter recalled Fellini taking "a little piece of brown paper tape" and sticking it near the viewfinder of the camera. Written on it was Ricordati che è un film comico ("Remember, this is a comedy"). [7]

8½ was filmed in the spherical cinematographic process, using 35-millimeter film, and exhibited with an aspect ratio of 1.78:1.

As with most Italian films of this period the sound was entirely dubbed in afterwards; following a technique dear to Fellini many lines of the dialogue were written only during post production, while the actors on the set mouthed random lines. This film marks the first time actress Claudia Cardinale was allowed to dub her own dialogue — previously her voice was thought to be too throaty and, coupled with her Tunisian accent, was considered undesirable.[8].

Critical reception

Selected Italian and French Reviews

First released in Italy on February 14, 1963, Otto e mezzo received virtually unanimous acclaim with reviewers hailing Fellini as "a genius possessed of a magic touch, a prodigious style."[9] Italian novelist and critic Alberto Moravia described the film's protagonist, Guido Anselmi, as "obsessed by eroticism, a sadist, a masochist, a self-mythologizer, an adulterer, a clown, a liar and a cheat. He's afraid of life and wants to return to his mother's womb... In some respects he resembles Leopold Bloom, the hero of James Joyce’s Ulysses, and we have the impression that Fellini has read and contemplated this book. The film is introverted, a sort of private monologue interspersed with glimpses of reality… Fellini’s dreams are always surprising and, in a figurative sense, original, but his memories are pervaded by a deeper, more delicate sentiment. This is why the two episodes concerning the hero’s childhood at the old country house in Romagna and his meeting with the woman on the beach in Rimini are the best of the film, and among the best of all Fellini’s works to date."[10]

Reviewing for Corriere della Sera, Giovanni Grazzini underlined that "the beauty of the film lies in its ‘confusion’… a mixture of error and truth, reality and dream, stylistic and human values, and in the complete harmony between Fellini’s cinematographic language and Guido’s rambling imagination. It is impossible to distinguish Fellini from his fictional director and so Fellini’s faults coincide with Guido’s spiritual doubts. The osmosis between art and life is amazing. It will be difficult to repeat this achievement…[11] Fellini's genius shines in everything here, as it has rarely shone in the movies. There isn't a set, a character or a situation that doesn't have a precise meaning on the great stage that is 8½."[12] Mario Verdone of Bianco e Nero insisted the film was "like a brilliant improvisation... The film became the most difficult feat the director ever tried to pull off. It is like a series of acrobats that a tight-rope walker tries to execute high above the crowd... always on the verge of falling and being smashed on the ground. But at just the right moment, the acrobat knows how to perform the right somersault: with a push he straightens up, saves himself and wins." [13]

In France, film director François Truffaut wrote: "Fellini's film is complete, simple, beautiful, honest, like the one Guido wants to make in 8½." [14] Premier Plan critics André Bouissy and Raymond Borde argued that the film "has the importance, magnitude, and technical mastery of Citizen Kane. It has aged twenty years of the avant-garde in one fell swoop because it both integrates and surpasses all the discoveries of experimental cinema."[15] Pierre Kast of Les Cahiers du Cinéma explained that "my admiration for Fellini is not without limits. For instance, I did not enjoy La strada but I did I vitelloni. But I think we must all admit that 8½, leaving aside for the moment all prejudice and reserve, is prodigious. Fantastic liberality, a total absence of precaution and hypocrisy, absolute dispassionate sincerity, artistic and financial courage - these are the characteristics of this incredible undertaking." [16]

Selected USA Reviews

Released in America on June 25, 1963 by Joseph E. Levine who'd bought the rights sight unseen, the film was screened at the Festival Theatre in New York in the presence of Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni. The acclaim was unanimous with the exception of reviews by Pauline Kael and John Simon: the former derided the film as a "structural disaster" while the latter considered it "a fiasco."[17] Audiences, however, loved it to such an extent that a company attempted to obtain the rights to mass-produce Guido Anselmi's black director's hat.[18]

New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther praised the film as "a piece of entertainment that will really make you sit up straight and think, a movie endowed with the challenge of a fascinating intellectual game... If Mr. Fellini has not produced another masterpiece - another all-powerful exposure of Italy's ironic sweet life - he has made a stimulating contemplation of what might be called, with equal irony, a sweet guy." [19] Archer Winsten of The New York Post interpreted the film as "a kind of review and summary of Fellini's picture-making" but doubted that it would appeal as directly to the American public as La dolce vita had three years earlier: "This is a subtler, more imaginative, less sensational piece of work. There will be more people here who consider it confused and confusing. And when they do understand what it is about - the simultaneous creation of a work of art, a philosophy of living together in happiness, and the imposition of each upon the other, they will not be as pleased as if they had attended the exposition of an international scandal." [20] In his 1993 review, Roger Ebert wrote that "it remains the definitive film about director's block."[21]

In 1987, a group of thirty European intellectuals and filmmakers voted Otto e mezzo the most important European film ever made.[22] It came number three on the 2002 Sight & Sound Director's Poll beaten only by Citizen Kane and The Godfather (Parts 1 and 2). 8½ is a fixture on the prestigious Sight & Sound critics' and directors' polls of the top ten films ever made. It ranks number three on the magazine's 2002 Directors' Top Ten Poll and number nine on the Critics' Top Ten Poll.[3] It is ranked as the 4th Best Foreign Language film of all time by the Screen Directory. [23]

Influence

Later in the year of the film's 1963 release, a group of young Italian writers founded Gruppo '63, a literary collective of the neoavanguardia comprised of novelists, reviewers, critics, and poets inspired by 8½ and Umberto Eco's seminal essay, Opera aperta (Open Work). [24]

"Imitations of 8½ pile up by directors all over the world," writes Fellini biographer Tullio Kezich.[25] The following is a short-list of the films it has inspired: Mickey One (Arthur Penn, 1965), Alex in Wonderland (Paul Mazursky, 1970), Beware of a Holy Whore (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1971), Day for Night (François Truffaut, 1973), All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979), Stardust Memories (Woody Allen, 1980), Sogni d'oro (Nanni Moretti, 1981), Parad Planet (Vadim Abdrashitov, 1984), La Pelicula del rey (Carlos Sorin, 1986), Living in Oblivion (Tom DiCillo, 1995) along with the successful Broadway musical, Nine ( Maury Yeston and Mario Fratti, 1982; revived 2003).[26]

Awards

8½ won two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design (black-and-white) while garnering three other nominations for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Art Direction (black-and-white). The New York Film Critics Circle also named 8½ best foreign language film.

The Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists awarded the movie all seven prizes for director, producer, original story, screenplay, music, cinematography, and best supporting actress (Sandra Milo). At the Saint Vincent Film Festival, it was awarded Grand Prize over Luchino Visconti's Il gattopardo (The Leopard).

Presented to an audience of 8,000 in the Kremlin's conference hall in 1963, the film won the prestigious Grand Prize at the Moscow Film Festival to acclaim that worried the Soviet festival authorities: the thunderous applause was "a cry for freedom." [27] Jury members included Stanley Kramer, Jean Marais, Satyajit Ray, and screenwriter Sergio Amidei. [28]

Notes

- ^ BBC - Films - review - Fellini 8½

- ^ Film scholar Charles Affron writes that "the status of 8½ as a 'classic' text can be recognized in the homage of its imitations and versions." Cf. Affron, 5. Fellini scholar Peter Bondanella concurs: "As might be expected from the work's important place in the history of the cinema, the criticism on 8½ is voluminous." Cf. Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 163

- ^ a b "Directors' Top Ten Poll". British Film Institute. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ "Screening the Past". Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 175

- ^ Quoted in Kezich, 234

- ^ Walter, Eugene. "Dinner with Fellini", The Transatlantic Review, Autumn 1964. Quoted in Affron, 267

- ^ 8½, Criterion Collection DVD, featured commentary track.

- ^ Kezich, 245

- ^ Moravia’s review first published in L’Espresso (Rome) on 17 February 1963. Quoted in Fava and Vigano, 115-116

- ^ Grazzini’s review first published in Corriere della Sera (Milan) on 16 February 1963. Quoted in Fava and Vigano, 116

- ^ This translation of Grazzini's review quoted in Affron, 255

- ^ Affron, 255

- ^ Truffaut's review first published in Lui (Paris), 1 July 1963. Affron, 257

- ^ First published in Premier Plan (Paris), 30 November 1963. Affron, 257

- ^ First published in Les Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July 1963. Fava and Vigano, 116

- ^ Kezich, 247

- ^ Kezich, 247

- ^ First published in the NYT, 26 June 1963. Fava and Vigano, 118

- ^ First published in The New York Post, 26 June 1963. Fava and Vigano, 118.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1993-05-07). "Reviews :: Fellini's 8 1/2". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ Bondanella, The Films of Federico Fellini, 93.

- ^ "Top Ten Listings: Foreign Language". The Screen Directory. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ Kezich, 246

- ^ Kezich, 249

- ^ Kezich, 249-250

- ^ Kezich, 247

- ^ Kezich, 248

References

- Affron, Charles. 8½: Federico Fellini, Director. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989.

- Bondanella, Peter. The Cinema of Federico Fellini. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Bondanella, Peter. The Films of Federico Fellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Fava, Claudio and Aldo Vigano. The Films of Federico Fellini. New York: Citadel Press, 1990.

- Kezich, Tullio. Federico Fellini: His Life and Work. New York: Faber and Faber, 2006.