Around the World in Eighty Days: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 24.15.190.132 (talk) to last version by BarnardKnox |

BarnardKnox (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

Further, the periodical ''Le Tour du monde'' ([[3 October]], [[1869]]) contained a short piece entitled "Around the World in Eighty Days", which refers to "140 miles" of railway not yet completed between Alahabad and Bombay, a central point in Verne's work. But even the ''Le Tour de monde'' article was not entirely original, it cites in its bibliography the ''Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, de la Géographie, de l'Histoire et de l'Archéologie'' (August, 1869), which also contains the title ''Around the World in Eighty Days'' in its contents page. The ''Nouvelles Annales'' were written by [[Conrad Malte-Brun]] (1775—1826) and his son [[Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun]] (1816—1889). Scholars believe Verne was aware of either the ''Le Tour de monde'' article, or the ''Nouvelles Annales'' (or both), and consulted it — the '''Le Tour du monde'' even included a trip schedule very similar to Verne's final version. |

Further, the periodical ''Le Tour du monde'' ([[3 October]], [[1869]]) contained a short piece entitled "Around the World in Eighty Days", which refers to "140 miles" of railway not yet completed between Alahabad and Bombay, a central point in Verne's work. But even the ''Le Tour de monde'' article was not entirely original, it cites in its bibliography the ''Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, de la Géographie, de l'Histoire et de l'Archéologie'' (August, 1869), which also contains the title ''Around the World in Eighty Days'' in its contents page. The ''Nouvelles Annales'' were written by [[Conrad Malte-Brun]] (1775—1826) and his son [[Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun]] (1816—1889). Scholars believe Verne was aware of either the ''Le Tour de monde'' article, or the ''Nouvelles Annales'' (or both), and consulted it — the '''Le Tour du monde'' even included a trip schedule very similar to Verne's final version. |

||

A possible inspiration was the traveller [[George Francis Train]], who made four trips around the world, including one in 80 days in 1870. Similarities include the hiring of a private train and his being imprisoned. Train later claimed "Verne stole my thunder. I'm Phileas Fogg." |

|||

Regarding the idea of gaining a day, Verne said of its origin: "I have a great number of scientific odds and ends in my head. It was thus that, when, one day in a Paris café, I read in the ''Siècle'' that a man could travel around the world in eighty days, it immediately struck me that I could profit by a difference of meridian and make my traveller gain or lose a day in his journey. There was a [[dénouement]] ready found. The story was not written until long after. I carry ideas about in my head for years – ten, or fifteen years, sometimes – before giving them form." In his lecture of April 1873 "The Meridians and the Calendar", Verne responded to a question about where the change of day actually occurred, since the [[international date line]] had only become current in 1880 and the Greenwich prime meridian was not adopted internationally until 1884. Verne cited an 1872 article in ''[[Nature (journal)|Nature]]'', and [[Edgar Allan Poe]]'s short story "Three Sundays in a Week" (1841), which was also based on going around the world and the difference in a day linked to a marriage at the end. Verne even analysed Poe's story in his ''Edgar Poe and His Works'' (1864). |

Regarding the idea of gaining a day, Verne said of its origin: "I have a great number of scientific odds and ends in my head. It was thus that, when, one day in a Paris café, I read in the ''Siècle'' that a man could travel around the world in eighty days, it immediately struck me that I could profit by a difference of meridian and make my traveller gain or lose a day in his journey. There was a [[dénouement]] ready found. The story was not written until long after. I carry ideas about in my head for years – ten, or fifteen years, sometimes – before giving them form." In his lecture of April 1873 "The Meridians and the Calendar", Verne responded to a question about where the change of day actually occurred, since the [[international date line]] had only become current in 1880 and the Greenwich prime meridian was not adopted internationally until 1884. Verne cited an 1872 article in ''[[Nature (journal)|Nature]]'', and [[Edgar Allan Poe]]'s short story "Three Sundays in a Week" (1841), which was also based on going around the world and the difference in a day linked to a marriage at the end. Verne even analysed Poe's story in his ''Edgar Poe and His Works'' (1864). |

||

Revision as of 11:33, 3 September 2009

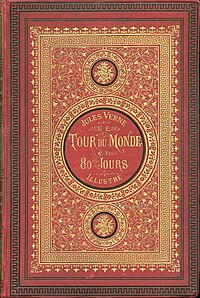

First edition cover from 1873 | |

| Author | Jules Verne |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours |

| Translator | George Makepeace Towle[1] |

| Illustrator | Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville and Léon Benett[2] |

| Language | French |

| Series | The Extraordinary Voyages #11 |

| Genre | Adventure novel |

| Publisher | Pierre-Jules Hetzel |

Publication date | January 30, 1873[3] |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1873 |

| Preceded by | The Fur Country |

| Followed by | The Mysterious Island |

Around the World in Eighty Days (French: Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours) is a classic adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in 1873. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate the world in 80 days on a £20,000 wager set by his friends at the Reform Club.

Plot summary

The story starts in London on October 2, 1872. Phileas Fogg is a wealthy English gentleman who lives unmarried in solitude at Number 7 Savile Row, Burlington Gardens. Despite his wealth, which is of unknown origin, Mr. Fogg, whose countenance is described as "repose in action", lives a modest life with habits carried out with mathematical precision. As is noted in the first chapter, very little can be said about Mr. Fogg's social life other than that he is a member of the Reform Club. Having dismissed his former valet, James Foster, for bringing him shaving water at 84 degrees Fahrenheit rather than the regular 86, Mr. Fogg hires the Frenchman Passepartout, of around 30 years of age, as a replacement.

Later, on that day, in the Reform Club, Fogg gets involved in an argument over an article in The Daily Telegraph, stating that with the opening of a new railway section in India, it is now possible to travel around the world in 80 days.

| London to Suez | rail and steamer | 7 days |

| Suez to Bombay | steamer | 12 days |

| Bombay to Calcutta | rail | 4 days |

| Calcutta to Hong Kong | steamer | 13 days |

| Hong Kong to Yokohama | steamer | 6 days |

| Yokohama to San Francisco | steamer | 22 days |

| San Francisco to New York | rail | 7 days |

| New York to London | steamer and rail | 9 days |

| Total | 80 days | |

He accepts a wager for £20,000 from his fellow club members, which he will receive if he makes it around the world in 80 days. Accompanied by his manservant Passepartout, he leaves London by train at 8.45 P.M. on October 2, 1872, and thus is due back at the Reform Club at the same time 80 days later, on December 21.

Fogg and Passepartout reach Suez in time. While disembarking in Egypt, they are watched by a Scotland Yard detective named Fix, who has been dispatched from London in search of a bank robber. Because Fogg matches the description of the bank robber, Fix mistakes Fogg for the criminal. Since he cannot secure a warrant in time, Fix goes on board the steamer conveying the travellers to Bombay. During the voyage, Fix becomes acquainted with Passepartout, without revealing his purpose. On the voyage, Fogg promises the engineer a large reward if he gets them to Bombay early. They dock two days ahead of schedule.

Now with two days extra, Fogg and Passepartout switch to the railway in Bombay, setting off for Calcutta, Fix now following them undercover. As it turns out that the construction of the railway is not totally finished, they are forced to get over the remaining gap between two stations by riding an elephant, which Phileas Fogg purchases at the prodigious price of 2,000 pounds.

During the ride, they come across a suttee procession, in which a young Parsi woman, Aouda, is led to a sanctuary to be sacrificed by the process of sati the next day by Brahmins. Since the young woman is drugged with the smoke of opium and hemp and obviously not going voluntarily, the travellers decide to rescue her. They follow the procession to the site, where Passepartout secretly takes the place of Aouda's deceased husband on the funeral pyre, on which she is to be burned the next morning. During the ceremony, he then rises from the pyre, scaring off the priests, and carries the young woman away. Due to this incident, the two days gained earlier are lost but Fogg does not show sign of regret.

The travellers then hasten on to catch the train at the next railway station, taking Aouda with them. At Calcutta, they can finally board a steamer going to Hong Kong. Fix, who had secretly been following them, has Fogg and Passepartout arrested in Calcutta. However, they jump bail and Fix is forced to follow them to Hong Kong. On board, he shows himself to Passepartout, who is delighted to meet again his travelling companion from the earlier voyage.

In Hong Kong, it turns out that Aouda's distant relative, in whose care they had been planning to leave her, has moved, likely to Holland, so they decide to take her with them to Europe. Meanwhile, still without a warrant, Fix sees Hong Kong as his last chance to arrest Fogg on British soil. He therefore confides in Passepartout, who does not believe a word and remains convinced that his master is not a bank robber. To prevent Passepartout from informing his master about the premature departure of their next vessel, Fix gets Passepartout drunk and drugs him in an opium den. In his dizziness, Passepartout yet manages to catch the steamer to Yokohama, but neglects to inform Fogg.

Fogg, on the next day, discovers that he has missed his connection. He goes in search of a vessel that will take him to Yokohama. He finds a pilot boat that takes him and his companion (Aouda) to Shanghai, where they catch a steamer to Yokohama. In Yokohama, they go on a search for Passepartout, believing that he may have arrived there with the original connection. They find him in a circus, trying to earn his homeward journey.

Reunited, the four board a steamer taking them across the Pacific to San Francisco. Fix promises Passepartout that now, having left British soil, he will no longer try to delay Fogg's journey, but rather support him in getting back to Britain as fast as possible (to have him arrested there).

In San Francisco they get on a trans-American train to New York, encountering a number of obstacles along the way: a massive herd of bison crossing the tracks, a failing suspension bridge, and most disasterously, the train is attacked and overcome by Sioux indians. After heroically uncoupling the locomotive from the carriages, Passepartout is kidnapped by the indians, but Fogg rescues him with the help of some volunteer military-men. The rest of the journey to New York is made by wind-powered sledge and train connections.

Once in New York, and having missed departure of The China by 35 minutes, Fogg starts looking for an alternative for the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. He finds a small steamboat, destined for Bordeaux. However, the captain of the boat refuses to take the company to Liverpool, whereupon Fogg consents to be taken to Bordeaux for the price of $2000 per passenger. On the voyage, he bribes the crew to mutiny and take course for Liverpool. Against hurricane winds and going on full steam all the time, the boat runs out of fuel after a few days. Fogg buys the boat at a very high price from the captain, soothing him thereby, and has the crew burn all the wooden parts to keep up the steam.

The companions arrive at Queenstown, Ireland, in time to reach London via Dublin and Liverpool before the deadline. However, once on British soil again, Fix produces a warrant and arrests Fogg. A short time later, the misunderstanding is cleared up—the actual bank robber had been caught three days earlier in Edinburgh.

In response to this, Fogg, in a rare moment of impulse, punches Fix, who immediately falls to the ground. However, Fogg has missed the train and returns to London five minutes late, assured that he has lost the wager.

In his London house the next day, he apologises to Aouda for bringing her with him, since he now has to live in poverty and cannot financially support her. Aouda suddenly confesses that she loves him and asks him to marry her, which he gladly accepts. He calls for Passepartout to notify the reverend. At the reverend's, Passepartout learns that he is mistaken in the date, which he takes to be Sunday but which actually is Saturday due to the fact that the party travelled east, thereby gaining a full day on their journey around the globe, by crossing the International Date Line. He did not notice this in the USA, since there were daily trains, and because he hired his own ship across the Atlantic.

Passepartout hurries back to Fogg, who immediately sets off for the Reform Club, where he arrives just in time to win the wager. Fogg marries Aouda and the journey around the world is complete.

Background and analysis

Around the World in Eighty Days was written during difficult times both for France and for Verne. It was during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) in which Verne was conscripted as a coastguard, he was having money difficulties (his previous works were not paid royalties), his father had died recently, and he had witnessed a public execution which had disturbed him. However despite all this, Verne was excited about his work on the new book, the idea of which came to him one afternoon in a Paris café while reading a newspaper (see "Origins" below).

The technological innovations of the 19th century had opened the possibility of rapid circumnavigation and the prospect fascinated Verne and his readership. In particular three technological breakthroughs occurred in 1869-70 that made a tourist-like around-the-world journey possible for the first time: the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in America (1869), the linking of the Indian railways across the sub-continent (1870), and the opening of the Suez Canal (1869). It was another notable mark in the end of an age of exploration and the start of an age of fully global tourism that could be enjoyed in relative comfort and safety. It sparked the imagination that anyone could sit down, draw up a schedule, buy tickets and travel around the world, a feat previously reserved for only the most heroic and hardy of adventurers.

Verne is often characterised as a futurist or science fiction author, but there is not a glimmer of science-fiction in this, his most popular work (at least in English speaking countries.) Rather than any futurism, it remains a memorable portrait of the British Empire "on which the sun never sets" at its very peak, drawn by an outsider. It is also interesting to note that, as of 2006, there has never been a critical edition of Around the World in Eighty Days. This is in part due to the poor translations available of his works, the stereotype of "science fiction” or "boys' literature.” However, Verne's works were being looked at more seriously in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, with new translations and scholarship appearing.

It is interesting to note that The China's departure from New York on the day of Fogg's arrival there constitutes a minor flaw in Verne's logic, because Fogg had already crossed the Pacific without accounting for the International Date Line so his entire journey across North America was apparently conducted with an erroneous belief about the date and day of the week. Had The China sailed in agreement with the published steamer schedule used by Fogg, it would have departed a day later than Fogg expected, and he would have been able to catch it in spite of arriving what he thought was a few minutes late.

The closing date of the novel, 22 December 1872, was also the same date as the serial publication. As it was being published serially for the first time, some readers believed that the journey was actually taking place — bets were placed, and some railway companies and ship liner companies actually lobbied Verne to appear in the book. It is unknown if Verne actually submitted to their requests, but the descriptions of some rail and shipping lines leave some suspicion he was influenced.

Although a journey by hot air balloon has become one of the images most strongly associated with the story, this iconic symbol was never deployed in the book by Verne himself – the idea is briefly brought up in chapter 32, but dismissed, it "would have been highly risky and, in any case, impossible." However the popular 1956 movie adaptation Around the World in Eighty Days floated the balloon idea, and it has now become a part of the mythology of the story, even appearing on book covers.This plot element is reminiscent of Verne's earlier Five Weeks in a Balloon which first made him a well-known author.

Following Towle and d'Anver's 1873 English translation, there have been many people who have tried to follow in the footsteps of Fogg's fictional circumnavigation, often within self-imposed constraints:

- 1889 – Nellie Bly undertook to travel around the world in 80 days for her newspaper, the New York World. She managed to do the journey within 72 days. Her book about the trip, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days, became a best seller.

- 1903 – James Willis Sayre, a Seattle theatre critic and arts promoter, set the world record for circling the earth using public transportation exclusively, completing his trip in 54 days, 9 hours, and 42 minutes.

- 1908 – Harry Bensley, on a wager, set out to circumnavigate the world on foot wearing an iron mask.

- 1988 – Monty Python alumnus Michael Palin took a similar challenge without using aircraft as a part of a television travelogue, called Michael Palin: Around the World in 80 Days. He completed the journey in 79 days and 7 hours.

- 1993–present – The Jules Verne Trophy is held by the boat that sails around the world without stopping, and with no outside assistance in the shortest time.

Origins

The idea of a trip around the world within a set period had clear external origins and was popular before Verne published his book in 1872. Even the title Around the World in Eighty Days is not original to Verne. About six sources have been suggested as the origins of the story:

Greek traveller Pausanias (c. 100 AD) wrote a work that was translated into French in 1797 as Voyage autour du monde ("Around the World"). Verne's friend, Jacques Arago, had written a very popular Voyage autour du monde in 1853. However in 1869/70 the idea of travelling around the world reached critical popular attention when three technological breakthroughs occurred: the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in America (1869), the linking of the Indian railways across the sub-continent (1870), and the opening of the Suez Canal (1869). In 1871 appeared Around the World by Steam, via Pacific Railway, published by the Union Pacific Railroad Company, and an Around the World in A Hundred and Twenty Days by Edmond Planchut. Between 1869 and 1871, an American William Perry Fogg went around the world describing his tour in a series of letters to the Cleveland Leader, titled Round the World: Letters from Japan, China, India, and Egypt (1872). Additionally, in early 1870, the Erie Railway Company published a statement of routes, times, and distances detailing a trip around the globe of 23,739 miles in seventy-seven days and twenty-one hours.[4]

In 1872 Thomas Cook organised the first around the world tourist trip, leaving on 20 September, 1872 and returning seven months later. The journey was described in a series of letters that were later published in 1873 as Letter from the Sea and from Foreign Lands, Descriptive of a tour Round the World. Scholars have pointed out similarities between Verne's account and Cook's letters, although some argue that Cook's trip happened too late to influence Verne. Verne, according to a second-hand 1898 account, refers to a Thomas Cook advertisement as a source for the idea of his book. In interviews in 1894 and 1904, Verne says the source was "through reading one day in a Paris cafe" and "due merely to a tourist advertisement seen by chance in the columns of a newspaper.” Around the World itself says the origins were a newspaper article. All of these point to Cook's advert as being a probable spark for the idea of the book.

Further, the periodical Le Tour du monde (3 October, 1869) contained a short piece entitled "Around the World in Eighty Days", which refers to "140 miles" of railway not yet completed between Alahabad and Bombay, a central point in Verne's work. But even the Le Tour de monde article was not entirely original, it cites in its bibliography the Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, de la Géographie, de l'Histoire et de l'Archéologie (August, 1869), which also contains the title Around the World in Eighty Days in its contents page. The Nouvelles Annales were written by Conrad Malte-Brun (1775—1826) and his son Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun (1816—1889). Scholars believe Verne was aware of either the Le Tour de monde article, or the Nouvelles Annales (or both), and consulted it — the 'Le Tour du monde even included a trip schedule very similar to Verne's final version.

A possible inspiration was the traveller George Francis Train, who made four trips around the world, including one in 80 days in 1870. Similarities include the hiring of a private train and his being imprisoned. Train later claimed "Verne stole my thunder. I'm Phileas Fogg."

Regarding the idea of gaining a day, Verne said of its origin: "I have a great number of scientific odds and ends in my head. It was thus that, when, one day in a Paris café, I read in the Siècle that a man could travel around the world in eighty days, it immediately struck me that I could profit by a difference of meridian and make my traveller gain or lose a day in his journey. There was a dénouement ready found. The story was not written until long after. I carry ideas about in my head for years – ten, or fifteen years, sometimes – before giving them form." In his lecture of April 1873 "The Meridians and the Calendar", Verne responded to a question about where the change of day actually occurred, since the international date line had only become current in 1880 and the Greenwich prime meridian was not adopted internationally until 1884. Verne cited an 1872 article in Nature, and Edgar Allan Poe's short story "Three Sundays in a Week" (1841), which was also based on going around the world and the difference in a day linked to a marriage at the end. Verne even analysed Poe's story in his Edgar Poe and His Works (1864).

In summary either the periodical 'Le Tour du monde or the Nouvelles Annales, W. P. Fogg, probably Thomas Cook's advert (and maybe his letters) would be the main likely source for the book. In addition, Poe's short story "Three Sundays in a Week" was clearly the inspiration for the lost day plot device.

Literary significance and criticism

Select quotes:

- "We will only remind readers en passant of Around the World in Eighty Days, that tour de force of Mr Verne's—and not the first he has produced. Here, however, he has summarised and concentrated himself, so to speak ... No praise of his collected works is strong enough .. they are truly useful, entertaining, poignant, and moral; and Europe and America have merely produced rivals that are remarkably similar to them, but in any case inferior." (Henry Trianon, Le Constitutionnel, December 20, 1873).

- "His first books, the shortest, Around the World or From the Earth to the Moon, are still the best in my view. However, the works should be judged as a whole rather than in detail, and on their results rather than their intrinsic quality. Over the last forty years, they have had an influence unequalled by any other books on the children of this and every country in Europe. And the influence has been good, in so far as can be judged today." (Léon Blum, L'Humanité, April 3, 1905).

- "Jules Verne's masterpiece .. stimulated our childhood and taught us more than all the atlases: the taste of adventure and the love of travel. 'Thirty thousand banknotes for you, Captain, if we reach Liverpool within the hour.' This cry of Phileas Fogg's remains for me the call of the sea." (Jean Cocteau, Mon premier voyage (Tour du monde en 80 jours), Gallimard, 1936).

- "Leo Tolstoy loved his works. 'Jules Verne's novels are matchless', he would say. 'I read them as an adult, and yet I remember they excited me. Jules Verne is an astonishing past master at the art of constructing a story that fascinates and impassions the reader. (Cyril Andreyev, "Preface to the Complete Works", trans. François Hirsch, Europe, 33: 112-113, 22-48).

- "Jules Verne's work is nothing but a long meditation, a reverie on the straight line—which represents the predication of nature on industry and industry on nature, and which is recounted as a tale of exploration. Title: the adventures of a straight line ... The train.. cleaves through nature, jumps obstacles .. and continues both the actual journey—whose form is a furrow—and the perfect embodiment of human industry. The machine has the additional advantage here of not being isolated in a purpose-built, artificial place, like the factory or all similar structures, but of remaining in permanent and direct contact with the variety of nature." Pierre Macherey (1966). [5]

Adaptations and influences

The book has been adapted many times in different forms.

Theatre

- A 1874 play written by Jules Verne and Adolphe d'Ennery at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin in Paris, where it was shown 415 times.[6]

- A stage musical adaptation premiered at the Fulton Opera House, Lancaster, PA in March 2007

- Orson Welles produced and starred in a stage version of the show that was only loosely faithful to Verne's original and had music and lyrics by Cole Porter. Numerous rewrites on tour did not improve what was a patchy effort not up to either Welles or Porter's other work, and the production was forgotten by all except the most devoted students of musical theatre.[who?][when?][citation needed]

- In 2001, the story was adapted for the stage by American playwright Mark Brown. In what has been described as "a wildly wacky, unbelievably creative, 90-miles-an-hour, hilarious journey" this award winning stage adaptation is written for five actors who portray thirty-nine characters.

- A musical version, 80 Days, with songs by Ray Davies of The Kinks and a book by playwright Snoo Wilson, directed by Des McAnuff, ran at the Mandell Weiss Theatre in San Diego from August 23 to October 9, 1988. The musical received mixed responses from the critics. Ray Davies's multi-faceted music, McAnuff's directing, and the acting, however, were well received, with the show winning the "Best Musical" award from the San Diego Theatre Critics Circle.[7]

- A musical version by Nicholas McCaig, see Around the World in 80 Days - A Musical Abstraction.

Films

- A 1919 silent black and white parody by director Richard Oswald didn't disguise its use of locations in Germany as placeholders for the international voyage; part of the movie's joke is that Fogg's trip is obviously going to places in and around Berlin. There are no remaining copies of the film available today.

- The best known version was released in 1956, with David Niven and Cantinflas heading a huge cast. Many famous performers play bit parts, and part of the pleasure in this movie is playing "spot the star". The movie earned five Oscars, out of eight nominations. This film was also responsible for the popular misconception that Fogg and company travel by balloon for part of the trip in the novel, which has prompted later adaptations to include similar sequences. See Around the World in Eighty Days (1956 film) for details.

- 1963 saw the release of The Three Stooges Go Around the World in a Daze. In this parody, the Three Stooges (Moe Howard, Larry Fine, and Joe DeRita) are cast as the menservants of Phileas Fogg III (Jay Sheffield), great-grandson of the original around-the-world voyager. When Phileas Fogg III is tricked into replicating his ancestor's feat of circumnavigation, Larry, Moe, and Curly-Joe dutifully accompany their master. Along the way, the boys get into and out of trouble in typical Stooge fashion.

- In 1983 the basic idea was expanded to a galactic scope in Japan's Ginga Shippu Sasuraiger, where a team of adventurers travel through the galaxy in a train-like ship that can transform into a giant robot. The characters are travelling to different planets in order to return within a certain period and win a bet.

- The story was again adapted for the screen in the 2004 film Around the World in 80 Days, starring Jackie Chan as Passepartout and Steve Coogan as Fogg. This version makes Passepartout the hero and the thief of the treasure of the Bank; Fogg's character is an eccentric inventor who bets a rival scientist that he can travel the world with (then) modern means of transportation.

TV

- An episode of the American television series, Have Gun - Will Travel, entitled "Fogg Bound", had the series' hero, Palladin (Richard Boone), escorting Phileas Fogg (Patric Knowles) through part of his journey. This episode was broadcasted by CBS on December 3, 1960.

- A 1989 three-part TV mini-series starred Pierce Brosnan as Fogg, Eric Idle as Passepartout, Peter Ustinov as Fix and several TV stars in cameo roles. The heroes travel a slightly different route than in the book and the script makes several contemporary celebrities part of the story who were not mentioned in the book. See Around the World in 80 Days (TV miniseries) for details.

- The BBC along with Michael Palin (of Monty Python fame) created a 1989 television travel series following the book's path. It was one of many travelogues Michael Palin has done with the BBC and was a commercially successful transition from his comedic career. The latest series in a similar format was Michael Palin's New Europe in 2007.

Animation

- An Indian Fantasy Story is an unfinished French/English co-production from 1938, featuring the wager at the Reform Club and the rescue of the Indian Princess. It was never completed as a full feature film.[8]

- Around the World in 79 Days, a serial segment on the Hanna-Barbera show The Cattanooga Cats from 1969 to 1971.

- Around the World in 80 days from 1972 by American studio Rankin/Bass with Japanese Mushi productions as part of the Festival of Family Classics series.

- A one-season cartoon series Around the World in Eighty Days from 1972 by Australian Air Programs International. NBC aired the series in the US during the 1972-73 season on Saturday mornings.

- Puss 'N Boots Travels Around the World, a 1976 anime from Toei Animation

- A Walt Disney adaptation was produced in 1986. It featured Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Goofy as the main characters.

- Around the World with Willy Fog by Spanish studio BRB Internacional from 1981 with a second season produced in 1993. This series depicts the characters as talking animals, and, despite adding some new characters and making some superficial modifications to the original story, it remains one of the most accurate adaptations of the book made for film or television. The show has gained a cult following in Finland, Britain, Germany and Spain. The first season is "Around the World in 80 Days", and the second season is "Journey to the Centre of the Earth" and "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea"; all three books are by Jules Verne.

- Tweety's High-Flying Adventure is a direct-to-video cartoon by Warner Brothers from 2000 starring the Looney Tunes characters. It takes a great many liberties with the original story, but the central idea is still there - indeed, one of the songs in this film is entitled Around the World in Eighty Days. Tweety not only had to travel the world, he had to also collect 80 cat pawprints, all while evading the constant pursuits of Slyvester. This movie frequently appears on various US-based cable TV networks.

- "Around the World in 80 Narfs" is a Pinky and the Brain episode where the Brain claims to be able to make the travel in less than 80 days and the Pompous Explorers club agrees to make him their new president. With this, the Brain expects to be UK's new Prime Minister, what he considers back at that time, the fastest way to take over the world.

- A Mickey Mouse episode shows the effort of Mickey to get around the world in 80 days with the help of Goofy. The cartoon made reference to the ending of the novel. They realise they have a day extra by hearing church bells on what they believe to be a Monday. This referenced the ending with the vicar in the church.

Exhibitions

- "Around the World in 80 Days", group show curated by Jens Hoffman at the ICA London 2006

Cultural references

- "Around the Universe in 80 Days" is a song by the Canadian band Klaatu, and makes reference to a spaceship travelling around the galaxy, coming home to find the Earth second from the Sun. It was originally included on the 1977 album "Hope", but also appears on at least two compilations.

- There are at least four board games by this name.

References

- William Butcher, ed. and trans., Around the World in Eighty Days, Oxford World's Classics (1995, 1999).

Footnotes

- ^

"How Lewis Mercier and Eleanor King Brought You Jules Verne". Retrieved 1008-10-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)Mercier is erroneously credited in some bibliographies with a translation of Around the World in 80 Days. The only reason for this attribution is the 1962 edition in England by Collier and in the U.S. by Doubleday of a "Junior Deluxe Edition" attributing the translation to "Mercier Lewis". There is no contemporary evidence of the existence of such a translation, and the book is in fact simply a bowdlerized version for young readers of Towle's 1873 translation.

— Norman M. Wolcott - ^ N.N.: Éditions Hetzel: Jules Verne - Cartonnages volumes simples: Le tour du monde en 80 jours. URL last accessed 2006-12-23.

- ^ Fehrmann, A.: Die Reise um die Erde in 80 Tagen. URL last accessed 2006-12-23.

- ^ The Kansas Daily Tribune, February 5, 1870.

- ^ Macherey, Pierre (1966). Pour une théorie de la production littéraire. Maspero.

- ^ http://pagesperso-orange.fr/anao/oeuvre/tourmonde.html ANAO (FR)

- ^ http://www.kinks.de/40jahre/teil6_e.html

- ^ "Cartoon Synopsis for An Indian Fantasy".

External links

Sources

- William Butcher, ed. and trans. Around the World in Eighty Days, Oxford University Press, translated, with an introduction, endnotes and other critical material. Most modern translation available on-line.

- Around the World in Eighty Days at Project Gutenberg Unknown translation.

- The Tour of the World in Eighty Days American edition, Butler Bros., 1887. From Google Books.

- Around the World in 80 Days, HTML version with additional content. Unknown translation.

- Around the World in Eighty Days, scanned illustrated early editions from Internet Archive.

- Around the World in Eighty Days - translation by George Makepeace Towle (1873). HTML format and pictures.

- Around the World in 80 Days,

- Around the World in 80 Days - Audibook from LibriVox

- Around the World in 80 Days, English translation with audio. (PDF)

- Template:Fr Around the World in Eighty Days, audio version

Misc

- Book and movie review by Rick Price - explains how this story and movie influenced generations to travel.