The Truman Show: Difference between revisions

Mytrumanshow (talk | contribs) |

Mytrumanshow (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

In August 2008, the ''[[British Journal of Psychiatry]]'' reported similar cases in the [[United Kingdom]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Fusar-Poli|first=P.|coauthors=Howes, O.; Valmaggia, L.; McGuire, P.|title='Truman' signs and vulnerability to psychosis|journal=Br J Psychiatry|volume=2008 |issue=193|pages=168|url=http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/193/2/168}}</ref> The delusion has informally been referred to as "Truman syndrome," according to an Associated Press story from 2008.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/28/fashion/28truman.html?_r=1|title=Look Closely, Doctor: See the Camera? |last=Kershaw|first=Sarah|date=2008-08-27|publisher=''[[The New York Times]]''|accessdate=2009-01-08}}</ref> |

In August 2008, the ''[[British Journal of Psychiatry]]'' reported similar cases in the [[United Kingdom]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Fusar-Poli|first=P.|coauthors=Howes, O.; Valmaggia, L.; McGuire, P.|title='Truman' signs and vulnerability to psychosis|journal=Br J Psychiatry|volume=2008 |issue=193|pages=168|url=http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/193/2/168}}</ref> The delusion has informally been referred to as "Truman syndrome," according to an Associated Press story from 2008.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/28/fashion/28truman.html?_r=1|title=Look Closely, Doctor: See the Camera? |last=Kershaw|first=Sarah|date=2008-08-27|publisher=''[[The New York Times]]''|accessdate=2009-01-08}}</ref> |

||

One gentleman even swears he is the "True Man" in the Truman Show, where people watch him because he is on a journey to be God[[MyTrumanShow]] |

One gentleman even swears he is the "True Man" in the Truman Show, where people watch him because he is on a journey to be God in [[MyTrumanShow]] |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 21:55, 15 December 2009

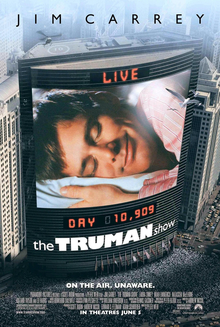

| The Truman Show | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Peter Weir |

| Written by | Andrew Niccol |

| Produced by | Scott Rudin Andrew Niccol Adam Schroeder |

| Starring | Jim Carrey Laura Linney Ed Harris Noah Emmerich Natascha McElhone |

| Cinematography | Peter Biziou |

| Edited by | William M. Anderson Lee Smith |

| Music by | Burkhard Dallwitz Philip Glass |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date | June 5, 1998 |

Running time | 103 min. |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60 million |

| Box office | $264.12 million |

The Truman Show is a 1998 comedy-drama film directed by Peter Weir and written by Andrew Niccol. The cast includes Jim Carrey as Truman Burbank, as well as Laura Linney, Noah Emmerich, Ed Harris and Natascha McElhone. The film chronicles the life of a man who discovers he is living in a constructed reality soap opera, televised 24/7 to billions across the globe.

The genesis of The Truman Show was a spec script by Niccol. The original draft was more in tone of a science fiction thriller, with the story set in New York City. Scott Rudin purchased the script, and instantly set the project up at Paramount Pictures. Brian de Palma was in contention to direct before Weir took over, managing to make the film for $60 million against the estimated $80 million budget. Niccol rewrote the script simultaneously as the filmmakers were waiting for Carrey's schedule to open up for filming. The majority of filming took place at Seaside, Florida, a master-planned community located in the Florida Panhandle.

The film was a financial and critical success, and Paramount's marketing approach for the film was similar to Forrest Gump. The Truman Show earned numerous nominations at the 71st Academy Awards, 56th Golden Globe Awards, 52nd British Academy Film Awards and The Saturn Awards. The Truman Show has been analyzed as a thesis on Christianity, simulated reality, existentialism and the forthcoming rise of reality television.

Plot

The movie is framed around the television show "The Truman Show." Its main character, Truman Burbank, has lived his entire life since before birth in front of cameras for the show, though he himself is unaware of this fact. Truman's life is filmed through thousands of hidden cameras, 24 hours a day and broadcast live around the world, allowing executive producer Christof to capture Truman's real emotion and human behavior when put in certain situations. Truman's hometown of Seahaven is a complete set built under a giant dome and populated by the show's actors and crew, allowing Christof to control every aspect of Truman's life, even the weather. To prevent Truman from discovering his false reality, Christof has invented means of dissuading his sense of exploration, including "killing" his father in a storm while on a fishing trip to instill in him a fear of the water. However, despite Christof's control, Truman has managed to behave in unexpected manners, in particular falling in love with an extra, Sylvia, instead of Meryl, the actress intended to be his wife. Though Sylvia is removed from the set quickly, her memory still resonates with him, and he secretly thinks of her outside of his marriage to Meryl. Sylvia subsequently starts a "Free Truman" campaign that fights to have Truman freed from the show.

In the film's present, during the 30th year "The Truman Show" has been on the air, Truman discovers facts that seem out of place, such as a spotlight that nearly hits him (quickly passed off by local radio as an airplane's dislodged landing light) and a "Truman Show" crew conversation on his car radio that is describing his morning commute into work. These events cause Truman to start wondering about his life, realizing much of the town seems to revolve around him. Stress on Meryl to continue her role causes their marriage to unravel. Truman seeks to get away from Seahaven but is blocked by the inability to arrange for flights, bus breakdowns, sudden masses of traffic, and an apparent nuclear meltdown. After Meryl breaks down and is taken off the show, Christof brings back Truman's father, hoping his presence will keep Truman from trying to leave. However, he only provides a temporary respite: Truman soon becomes isolated and begins staying alone in his basement. One night, Truman manages to escape the basement undetected via a secret tunnel, forcing Christof to temporarily suspend broadcasting of the show for the first time in its history. This causes a surge in viewership, with many viewers, including Sylvia, cheering on Truman's escape attempt.

Christof orders every actor and crew member to search the town, breaking the town's daylight cycle to help in the search. They find that Truman has managed to overcome his fear of the water and has been sailing away from the town in a small boat named Santa Maria (the name of the ship in which Christopher Columbus discovered the New World). After restoring the broadcast, Christof orders the show's crew to create a large storm to try to capsize the boat. However, Truman's determination eventually leads Christof to terminate the storm. As Truman recovers, the boat reaches the edge of the dome, its bow piercing through the dome's painted sky. An awe-struck Truman then discovers a flight of stairs nearby, leading to a door marked "exit". As he contemplates leaving his world, Christof speaks directly to Truman via a powerful sound system, trying to persuade him to stay and arguing that there is no more truth in the real world than there is in his own, artificial world. Truman, after a moment's thought, delivers his catchphrase, "In case I don't see you ... good afternoon, good evening, and good night," bows to his audience, and steps through the door and into the real world. The assembled television viewers excitedly celebrate Truman's escape, and Sylvia quickly leaves her apartment to reunite with him. A network executive orders the crew to cease transmission. With the show completed, members of Truman's former audience are shown looking for something else to watch.

Cast

- Jim Carrey as Truman Burbank: Chosen out of five unwanted pregnancies and the first child to be legally adopted by a corporation. He is unaware that his daily life is broadcast 24 hours a day around the world. He has a job in the insurance business and a lovely wife, but he eventually notices that his environment is not what it seems to be. Robin Williams was considered for the role, but Weir cast Carrey after seeing him in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective because Carrey's performance reminded him of Charlie Chaplin.[1] Carrey took the opportunity to proclaim himself as a dramatic actor, rather than being typecast in comedic roles.[2] Carrey, who is normally paid $20 million per film, agreed to do The Truman Show for $12 million.[3] Carrey and Weir initially found working together on set difficult (Carrey's contract gave him the power to demand rewrites), but Weir was impressed with Carrey's improvisational skills, and the two became more interactive.[1] The scene wherein Truman declares "this planet Trumania of the Burbank galaxy" to the bathroom mirror was Carrey's idea.[4]

- Laura Linney as Meryl/Hannah Gill: Hannah Gill plays Truman's wife, who holds a profession as a nurse at the local hospital. Since the show relies on product placement for revenue, Meryl regularly shows off various items she has recently "purchased," one of the many oddities that makes Truman question his life. Her role is essentially to act the part of Truman's wife and ultimately to have a child by him, despite her reluctance to accomplish either. Linney explains that "she was a child actress who never made it, and now she's really ambitious. Mostly she's into negotiating her contract. Every time she sleeps with Truman she gets an extra $10,000".[1] Linney heavily studied Sears catalogs from the 1950s to develop her character's poses.[5]

- Noah Emmerich as Marlon/Louis Coltrane: Louis Coltrane plays Truman's best friend since early childhood. Marlon is a vending machine operator for the company Goodies, who promises Truman he would never lie to him, despite the latest events in Truman's life. Emmerich has said, "My character is in a lot of pain. He feels really guilty about deceiving Truman. He's had a serious drug addiction for many years. Been in and out of rehab"[1].

- Ed Harris as Christof: The creator of The Truman Show. Christof remains dedicated to the program at all costs, often overseeing and directing its course in person (rather than through aides), but at the climax/resolution, he speaks to Truman over a loudspeaker, revealing the nature of Truman's situation. Dennis Hopper was originally cast in the role, but he left in April 1997 (during filming) over "creative differences." Harris was a last-minute replacement.[3] A number of other actors had turned down the role after Hopper's departure.[4] Harris had an idea of making Christof a hunchback, but Weir did not like the idea.[1]

- Natascha McElhone as Lauren/Sylvia: Sylvia was hired as Lauren, one of several extras. She became romantically involved with Truman and tried to reveal to him the truth about his life, but she was thrown out of the show before she could do so. Thereafter, she protests against The Truman Show, urging Christof to release its lead.

- Brian Delate as Walter Moore / Kirk Burbank: An actor who portrays Truman's father. When Truman was a boy, his character on the show was killed off to instill a fear of water in his son that would prevent Truman from leaving the set; however, he kept sneaking back into the show time and again. When Truman begins to question his staged life and tries to get away from it, the writers are forced to write a plot in which Kirk had not drowned but had suffered from amnesia.

- Holland Taylor as Alanis Montclair / Angela Burbank: Truman's mother. Christof orders that she attempt to persuade Truman to have children.

- Harry Shearer cameos as Mike Michaelson, news anchor host of TruTalk, an affiliate of The Truman Show.

- Paul Giamatti plays a control room director. Peter Krause portrays Truman's boss at his office.

- John Pramik plays as a keyboard artist on the set during the reunion of Truman and his father.

Production

Andrew Niccol completed a one-page film treatment titled The Malcolm Show in May 1991.[6] The original draft was more in tone of a science fiction thriller, with the story set in New York City.[5] Niccol stated, "I think everyone questions the authenticity of their lives at certain points. It's like when kids ask if they're adopted".[7] In the fall of 1993,[8] producer Scott Rudin purchased the script for slightly over $1 million.[9] Paramount Pictures instantly agreed to distribute. Part of the deal called for Niccol to have his directing debut, though Paramount felt the estimated $80 million budget would be too high for him.[10] In addition, Paramount wanted to go with an A-list director, paying Niccol extra money "to step aside." Brian de Palma was under negotiations to direct before he left United Talent Agency in March 1994.[8] Directors being considered after de Palma's departure included Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, Barry Sonnenfeld and Steven Spielberg before Peter Weir signed on in early 1995,[1] following a recommendation of Niccol.[7]

Paramount was cautious about The Truman Show, which they dubbed "the most expensive art film ever made" because of its $60 million budget. They wanted the film to be funnier and less dramatic.[1] Weir also shared this vision, feeling that Niccol's script was too dark, and declaring "where he [Niccol] had it depressing, I could make it light. It could convince audiences they could watch a show in this scope 24/7." Niccol wrote sixteen drafts of the script before Weir considered the script ready for filming. Later on in 1995, Jim Carrey signed to star,[5] but because of commitments with The Cable Guy and Liar Liar, he would not be ready to start filming for at least another year.[1] Weir felt Carrey was perfect for the role and opted to wait for another year rather than recast the role.[5] Niccol rewrote the script twelve times,[1] while Weir created a fictionalized book about the show's history. He envisioned backstories for the characters and encouraged actors to do the same.[5]

Weir scouted locations in Eastern Florida but was unsatisfied with the landscapes. Sound stages at Universal Studios were reserved for the story's setting of Seahaven before Weir's wife introduced him to Seaside, Florida, a master-planned community located in the Florida Panhandle. Pre-production offices were instantly opened in Seaside, where the majority of filming took place. Other scenes were shot at Paramount Studios in Los Angeles, California.[4] Norman Rockwell paintings and 1960s postcards were used as inspiration for the film's design.[11][12] Weir, Peter Biziou and Dennis Gassner researched surveillance techniques for certain shots.[11]

Weir saw The Truman Show as a chance to use the long-abandoned silent-era cinematic technique of vignetting the edges of the frame to emphasize the center. The overall look was influenced by television images, particularly commercials: Many shots have characters leaning into the lens with their eyeballs wide open, and the interior scenes are heavily lit, because Weir wanted to remind viewers that "in this world, everything was for sale."[11] Those involved in visual effects work found the film somewhat difficult to make, because 1997 was the year many visual effects companies were trying to convert to computer-generated imagery.[12] CGI was used to create the upper halves of some of the larger buildings in the film's downtown set. Craig Barron, one of the effects supervisors, said that these digital models did not have to look as detailed and weathered as they normally would in a film because of the artificial look of the entire town, although they did imitate slight blemishes found in the physical buildings.[13]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

The original music for The Truman Show was composed by Burkhard Dallwitz. Dallwitz was hired after Peter Weir received a tape of his work while in Australia for the post-production.[14] Some parts of the soundtrack were composed by Philip Glass, including four pieces which appeared in his previous works (Powaqqatsi, Anima Mundi, and Mishima). Glass also appears very briefly in the film as one of the in-studio composer/performers.

Also featured in the film are Frederic Chopin's "Romance-Larghetto" from his first piano concerto, performed by Arthur Rubinstein, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's "Rondo Alla Turca" from his Piano Sonata No. 11 in A Major, performed by Wilhelm Kempff, Wojciech Kilar's "Father Kolbe's Preaching" performed by the Orchestra Philharmonique National de Pologne and "20th Century Boy" performed by rockabilly band The Big Six.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Trutalk" | Burkhard Dallwitz | 1:18 |

| 2. | "It's a Life" | Dallwitz | 1:30 |

| 3. | "Aquaphobia" | Dallwitz | 0:40 |

| 4. | "Dreaming of Fiji" | Philip Glass | 1:54 |

| 5. | "Flashback" | Dallwitz | 1:19 |

| 6. | "Anthem - Part 2" | Glass | 3:50 |

| 7. | "The Beginning" | Glass | 4:06 |

| 8. | "Romance-Larghetto" | Frederic Chopin | 10:42 |

| 9. | "Drive" | Dallwitz | 3:34 |

| 10. | "Underground" | Dallwitz | 0:56 |

| 11. | "Do Something!" | Dallwitz | 0:44 |

| 12. | "Living Waters" | Glass | 3:48 |

| 13. | "Reunion" | Dallwitz | 2:26 |

| 14. | "Truman Sleeps" | Glass | 1:51 |

| 15. | "Truman Sets Sail" | Dallwitz | 1:55 |

| 16. | "Underground/Storm" | Dallwitz | 3:37 |

| 17. | "Raising the Sail" | Glass | 2:13 |

| 18. | "Father Kolbe's Preaching" | Wojciech Kilar | 2:26 |

| 19. | "Opening" | Glass | 2:14 |

| 20. | "A New Life" | Dallwitz | 1:58 |

| 21. | "20th Century Boy" (performed by The Big Six) | Marc Bolan | 3:07 |

Themes

Religious analogy

Benson Y. Parkinson of the Association for Mormon Letters noted that Christof represented Jesus as an "off-Christ" ("Christ-off") or Antichrist. Parkinson further explained that Christof can be translated into Satan as megalomaniacal Hollywood producer. Truman and Sylvia are the only characters who use their real names on the show, which is to say their real names are also stage names.[15] Truman's search of evidence for the truth can be compared to a common man's opinion of life. Christof is willing to manipulate and use Truman for commercial gain, just as producers and directors sometimes use up their creative people and then discard them.[15] The conversation between Truman and Marlon at the bridge can be compared to one between Moses and God in the Bible.[15]

In "C.S. Lewis and Narnia for Dummies" by Richard Wagner, Christof is compared with Screwtape, the eponymous character of The Screwtape Letters by C. S. Lewis.[16] In this example, Christof manipulates Truman for his own personal ends, much as Screwtape instructs his nephew Wormwood to manipulate his patient. Screwtape instructs Wormwood that he "should be guarding him like the apple of your eye."[17] Similarly, one of the workers in the control room wears a T-shirt that reads, "love him, protect him." Finally, both Truman and the patient leave the world: Truman by walking through a door and the patient by dying. Screwtape described the action in the book by saying, "He got through so easily! Sheer, instantaneous liberation."[17]

Media

"This was a dangerous film to make because it couldn't happen. How ironic".

—Director Peter Weir on The Truman Show predicting the rise of reality television[4]

In 2008, Popular Mechanics named The Truman Show as one of the ten most prophetic science fiction films. Journalist Erik Sofge argued that the story reflects the falseness of reality television. "Truman simply lives, and the show's popularity is its straightforward voyeurism. And, like Big Brother, Survivor, and every other reality show on the air, none of his environment is actually real." He deemed it an eerie coincidence that Big Brother made its debut a year after the film's release, and he also compared the film to the 2003 program The Joe Schmo Show: "Unlike Truman, Matt Gould could see the cameras, but all of the other contestants were paid actors, playing the part of various reality-show stereotypes. While Matt eventually got all of the prizes in the rigged contest, the show's central running joke was in the same existential ballpark as The Truman Show."[18] Weir declared, "There has always been this question: Is the audience getting dumber? Or are we filmmakers patronizing them? Is this what they want? Or is this what we're giving them? But the public went to my film in large numbers. And that has to be encouraging."[7]

Ronald Bishop of Sage Journals Online thought The Truman Show showcased the power of the media. Truman's life inspires audiences around the world, meaning their lives are controlled by his. Bishop commented, "In the end, the power of the media is affirmed rather than challenged. In the spirit of Antonio Gramsci's concept of hegemony, these films and television programs co-opt our enchantment (and disenchantment) with the media and sell it back to us."[19]

Psychological interpretation

An essay published in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis analyzed Truman as a prototypical adolescent at the beginning of the movie. He feels trapped into a familial and social world to which he tries to conform while being unable to entirely identify with it, believing that he has no other choice (other than through the fantasy of fleeing to a far-way island). Eventually, Truman gains sufficient awareness of his condition to "leave home" — developing a more mature and authentic identity as a man, leaving his child-self behind and becoming a True-man.[20]

Utopia

Parallels can be drawn from Thomas More's 1516 book Utopia, in which More describes an island with only one entrance and only one exit. Only those who belonged to this island knew how to navigate their way through the treacherous openings safely and unharmed. This situation is similar to the The Truman Show because there are limited entryways into the world that Truman knows. Truman does not belong to this utopia into which he has been implanted, and childhood trauma rendered him frightened of the prospect of ever leaving this small community. Utopian models of the past tended to be full of like-minded individuals who shared much in common, comparable to More's Utopia and real-life groups such as the Shakers and the Oneida Community.[21] It is clear that the people in Truman's world are like-minded in their common effort to keep him oblivious to reality. The suburban "picket fence" appearance of the show's set is reminiscent of the "American Dream" of the 1950s. The "American Dream" concept in Truman's world serves to keep him happy and ignorant.[21]

Hamlet

Author Gregory Feeley noted parallels with Hamlet by William Shakespeare. In each story, a charismatic young man of great potential, admired by everyone in his tiny, insular community, falls unaccountably prey to a mysterious malaise. Everyone wants him to feel better but assures him that he will recover only if only he stops questioning the status quo. His mother wishes him to stop worrying and enjoy life; so does the best friend who is maneuvered into his path at every turn. The love of a loyal woman is dangled before him, and he is urged to give up all thought of traveling elsewhere. But there is some mystery involving his beloved, dead father, who has made an electrifying appearance before him. And everything seems to be controlled by a second, seemingly father-like figure, who claims to have the protagonist's true interests at heart but who makes his continued inquiries increasingly perilous. Despite several changes — The Truman Show offers two Ophelia figures and replaces Horatio with a best friend who conflates Rosencrantz and Guildenstern — the thematic parallel seems marked. Truman, like Hamlet, is an everyman figure, driven to question the nature of existence despite the urgings of those around him.[22]

Release

Reaction

The Truman Show's original theatrical release date was August 8, 1998, but Paramount Pictures considered pushing it back to around Christmas.[23] NBC purchased broadcast rights in December 1997, roughly eight months before the film's release.[24] In March 2000, Turner Broadcasting System purchased the rights and now often airs the film on TBS.[25]

Paramount's marketing approach for The Truman Show was similar to the one employed for Forrest Gump.[7][clarification needed] The film opened in the United States on June 5, 1998, and earned $31,542,121 in its opening weekend. It became a financial success that grossed a total of $264,118,201 ($125,618,201 in North America and $138,500,000 in foreign countries).[26] The Truman Show was the eleventh-highest grossing film of 1998.[27]

Based on 96 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, The Truman Show received an average 95% overall approval rating;[28], including a 90% among 20 critics in Rotten Tomatoes' "Top Critics" poll.[29] By comparison, Metacritic gave the film an average score of 90 from the 30 reviews collected.[30] Roger Ebert, comparing it to Forrest Gump, thought the film had a right balance of comedy and drama. He was also impressed with Jim Carrey's dramatic performance.[31] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "The Truman Show is emotionally involving without losing the ability to raise sharp satiric questions as well as get numerous laughs. The rare film that is disturbing despite working beautifully within standard industry norms."[32]

James Berardinelli liked the film's approach of "not being the casual summer blockbuster with special effects," and he likened Carrey's performance to those of Tom Hanks and James Stewart.[33] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader wrote, "Undeniably provocative and reasonably entertaining, The Truman Show is one of those high-concept movies whose concept is both clever and dumb."[34] Tom Meek of Film Threat said the film was not funny enough but still found "something rewarding in its quirky demeanor,"[35] In a more negative assessment, Fernando F. Croce of Slant Magazine described The Truman Show as highly "overrated, definitely not the-movie-of-the-decade as so many have claimed."[36]

Awards

At the 71st Academy Awards, The Truman Show was nominated for three categories but did not win any awards. Peter Weir received the nomination for Best Director, while Ed Harris was nominated for Best Supporting Actor and Andrew Niccol was nominated for Best Original Screenplay.[37] Many believed Carrey would be nominated for Best Actor, but he was not.[1] In contrast, the film was an outstanding success at the 56th Golden Globe Awards. Carrey (Best Actor - Motion Picture Drama), Harris (Best Supporting Actor - Motion Picture) and Burkhard Dallwitz and Philip Glass (Best Original Score) all won their respective categories. In addition The Truman Show earned a nomination for Best Motion Picture - Drama, and Weir (Director - Motion Picture) and Niccol (Screenplay) also received nominations.[38]

At the 52nd British Academy Film Awards, Weir (Direction), Niccol (Original Screenplay) and Dennis Gassner (Production Design) received awards. In addition, the film was nominated for Best Film and Best Visual Effects. Harris was nominated for Best Supporting Actor, and Peter Biziou was nominated for Best Cinematography.[39] The Truman Show was a success at The Saturn Awards, where it won the Best Fantasy Film and the Best Writing (Niccol). Carrey (Best Actor), Harris (Best Supporting Actor) and Weir (Direction) also received nominations.[40] Finally, the film won speculative fiction's Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[41]

Fictional antecedents

Many science fiction stories have been based on the idea of a character's unwitting role as an actor in a reality show. An early example with many parallels to The Truman Show is Damon Knight's 1955 story "You're Another",[42] in which the protagonist, Johnny, discovers that he is the star of a "livie", a show watched by millions of people in the future, where a director and crew control the events in his life according to a script.

The plot of The Truman Show is also similar to that of "Special Service" (The New Twilight Zone) where the main character is unknowingly the subject of a reality show.

The 1959 Philip K. Dick novel "Time Out Of Joint" is the story of a man who realizes that the town he lives in has been constructed and populated by actors in order to imprison him without his knowledge.

"The Truman Show Delusion"

Joel Gold, director of psychiatrics at the Bellevue Hospital Center, revealed that by 2008, he had met five patients with schizophrenia (and heard of another twelve) who believed their lives were reality television shows. Gold named the syndrome after the film and attributed the delusion to a world that had become hungry for publicity. Gold stated that some patients were rendered happy by their disease, while "others were tormented. One traveled to New York to check whether the World Trade Center had actually fallen — believing 9/11 to be an elaborate plot twist in his personal storyline. Another came to climb the Statue of Liberty, believing that he'd be reunited with his high-school girlfriend at the top and finally be released from the 'show.'"[43]

In August 2008, the British Journal of Psychiatry reported similar cases in the United Kingdom.[44] The delusion has informally been referred to as "Truman syndrome," according to an Associated Press story from 2008.[45]

One gentleman even swears he is the "True Man" in the Truman Show, where people watch him because he is on a journey to be God in MyTrumanShow

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Svetkey, Benjamin (1998-06-05). "The Truman Pro". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Weinraub, Bernard (1998-05-21). "Director Tries a Fantasy As He Questions Reality". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Busch, Anita M. (1997-04-07). "New Truman villain: Harris". Variety. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d How's It Going to End? The Making of The Truman Show, Part 2. Paramount Pictures. 2005.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e How's It Going to End? The Making of The Truman Show, Part 1. Paramount Pictures. 2005.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Benedict Carver (1998-06-22). "'Truman' suit retort". Variety. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Sheila (1998-09-20). "Interview: The clevering-up of America". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Fleming, Michael (1994-03-10). "SNL's Farley crashes filmdom". Variety. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Fleming, Michael (1994-02-18). "TriStar acquires female bounty hunter project". Variety. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Blackwelder, Rob (2002-08-12). "S1M0NE'S SIRE". Spliced Wire. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c Rudolph, Eric (June 1998). "This is Your Life". American Cinematographer. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Faux Finishing, the Visual Effects of The Truman Show. Paramount Pictures. 2005.

{{cite AV media}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Rickitt, Richard (2000). Special Effects: The History and Technique. Billboard Books. pp. 207–208. ISBN 0-8230-7733-0.

- ^ "Burkhard Dallwitz". Australian Musician. Autumn 1999. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Parkinson, Benson (2003-09-19). "The Literary Combine: Intimations of Immortality on The Truman Show". Association for Mormon Letters. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ Wagner, Richard (2005). "C.S. Lewis and Narnia for Dummies": 179.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Lewis, C.S. (1942). "The Screwtape Letters".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sofge, Erik (2008-03-28). "The 10 Most Prophetic Sci-Fi Movies Ever". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bishop, Ronald (2000-06-18). "Good Afternoon, Good Evening, and Good Night: The Truman Show as Media Criticism". Sage Journals Online. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ^ Brearley M, Sabbadini A. (2008). "The Truman Show : How's it going to end?". International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 89 (2): 433–40. doi:10.1111/j.1745-8315.2008.00030.x. PMID 18405297.

- ^ a b Beuka, Robert. SuburbiaNation: Reading Suburban Landscape in Twentieth Century American Fiction and Film. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004. ix-284.

- ^ "The Truman Show: Another Retelling of Hamlet". His blog. 2008-11-28. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ^ Hindes, Andrew (1997-04-10). "Speed 2 shifted in sked scramble". Variety. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hontz, Jenny (1997-12-18). "Peacock buys Par pic pack". Variety. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Turner Broadcasting Acquires Runaway Bride, Deep Impact, The Truman Show, Forrest Gump and Others in Film Deal With Paramount". Business Wire. 2000-03-06.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The Truman Show". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "1998 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "The Truman Show". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "The Truman Show: Rotten Tomatoes' Top Critics". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Truman Show, The (1998): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1998-06-05). "The Truman Show". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Turna, Kenneth (1998-06-05). "The Truman Show". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Berardinelli, James (1998-06-05]). "The Truman Show". ReelViews. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "The Audience Is Us". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Meek, Tom. "The Truman Show". Film Threat. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Croce, Fernando F. "The Truman Show". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "Academy Awards: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "Golden Globes: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ "Saturn Awards: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ "Hugo Awards: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ Knight, Damon (1961). Far Out. New York: Simon and Schuster.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ellison, Jesse (2008-08-02). "When Life Is Like a TV Show". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Fusar-Poli, P. "'Truman' signs and vulnerability to psychosis". Br J Psychiatry. 2008 (193): 168.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kershaw, Sarah (2008-08-27). "Look Closely, Doctor: See the Camera?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

External links

- Mercadante, Linda A. (2001-10-02). "The God Behind the Screen: Pleasantville & The Truman Show". University of Nebraska at Omaha.

- Goldman, Peter (2004-09-13). "Consumer Society and its Discontents: The Truman Show and The Day of the Locust". Westminister College.

- Hertenstein, Mike (2000-07-13). "The Truth May Be "Out There": The Question Is Can We Get There From Here?". Imaginarium Online.

- The Truman Show at IMDb

- The Truman Show at AllMovie

- The Truman Show at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Truman Show at Box Office Mojo