Kidney: Difference between revisions

Tassedethe (talk | contribs) rv unexplained deletion |

|||

| Line 167: | Line 167: | ||

{{main|Renal failure}} |

{{main|Renal failure}} |

||

Generally, humans can live normally with just one |

Generally, humans can live normally with just one or two kidneys, as one has more functioning renal tissue than is needed to survive. Only when the amount of functioning kidney tissue is greatly diminished will [[chronic kidney disease]] develop. [[Renal replacement therapy]], in the form of [[dialysis]] or [[kidney transplantation]], is indicated when the [[glomerular filtration rate]] has fallen very low or if the renal dysfunction leads to severe symptoms. |

||

==In other animals== |

==In other animals== |

||

Revision as of 09:55, 5 February 2010

| Latin = ren | |

|---|---|

Human kidneys viewed from behind with spine removed | |

Lamb kidneys | |

| Details | |

| Artery | renal artery |

| Vein | renal vein |

| Nerve | renal plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D007668 |

| TA98 | A08.1.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3358 |

| FMA | 7203 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The kidneys are paired organs, which have the production of urine as their primary function. Kidneys are seen in many types of animals, including vertebrates and some invertebrates. They are an essential part of the urinary system, but have several secondary functions concerned with homeostatic functions. These include the regulation of electrolytes, acid-base balance, and blood pressure. In producing urine, the kidneys excrete wastes such as urea and ammonium; the kidneys also are responsible for the reabsorption of glucose and amino acids. Finally, the kidneys are important in the production of hormones including calcitriol, renin and erythropoietin.

Located behind the abdominal cavity in the retroperitoneum, the kidneys receive blood from the paired renal arteries, and drain into the paired renal veins. Each kidney excretes urine into a ureter, itself a paired structure that empties into the urinary bladder.

Renal physiology is the study of kidney function, while nephrology is the medical specialty concerned with diseases of the nephron, which is the functional unit of the kidney. Diseases of the kidney are diverse, but individuals with kidney disease frequently display characteristic clinical features. Common clinical presentations include the nephritic and nephrotic syndromes, acute kidney failure, chronic kidney disease, urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis, and urinary tract obstruction.[1]

Anatomy

Location

In humans, the kidneys are located behind the abdominal cavity, in a space called the retroperitoneum. There are two, one on each side of the spine; they are approximately at the vertebral level T12 to L3.[2] The right kidney sits just below the diaphragm and posterior to the liver, the left below the diaphragm and posterior to the spleen. Resting on top of each kidney is an adrenal gland (also called the suprarenal gland). The asymmetry within the abdominal cavity caused by the liver typically results in the right kidney being slightly lower than the left, and left kidney being located slightly more medial than the right.[3][4] The upper (cranial) parts of the kidneys are partially protected by the eleventh and twelfth ribs, and each whole kidney and adrenal gland are surrounded by two layers of fat (the perirenal and pararenal fat) and the renal fascia. Each adult kidney weighs between 125 and 170 g in males and between 115 and 155 g in females.[2] The left kidney is typically slightly larger than the right.[citation needed]

Structure

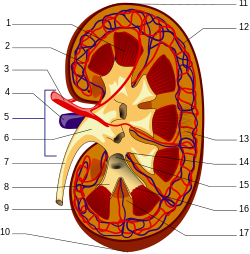

The kidney has a bean-shaped structure, each kidney has concave and convex surfaces. The concave surface, the renal hilum, is the point at which the renal artery enters the organ, and the renal vein and ureter leave. The kidney is surrounded by tough fibrous tissue, the renal capsule, which is itself surrounded by perinephric fat, renal fascia (of Gerota) and paranephric fat. The anterior (front) border of these tissues is the peritoneum, while the posterior (rear) border is the transversalis fascia.

The superior border of the right kidney is adjacent to the liver; and the spleen, for the left border. So, both, move down on inspiration.

The substance, or parenchyma, of the kidney is divided into two major structures: superficial is the renal cortex and deep is the renal medulla. Grossly, these structures take the shape of 8 to 18 cone-shaped renal lobes, each containing renal cortex surrounding a portion of medulla called a renal pyramid (of Malpighi).[2] Between the renal pyramids are projections of cortex called renal columns (of Bertin). Nephrons, the urine-producing functional structures of the kidney, span the cortex and medulla. The initial filtering portion of a nephron is the renal corpuscle, located in the cortex, which is followed by a renal tubule that passes from the cortex deep into the medullary pyramids. Part of the renal cortex, a medullary ray is a collection of renal tubules that drain into a single collecting duct.

The tip, or papilla, of each pyramid empties urine into a minor calyx, minor calyces empty into major calyces, and major calyces empty into the renal pelvis, which becomes the ureter.

Blood supply

The kidneys receive blood from the renal arteries, left and right, which branch directly from the abdominal aorta. Despite their relatively small size, the kidneys receive approximately 20% of the cardiac output.[2]

Each renal artery branches into segmental arteries, dividing further into interlobar arteries which penetrate the renal capsule and extend through the renal columns between the renal pyramids. The interlobar arteries then supply blood to the arcuate arteries that run through the boundary of the cortex and the medulla. Each arcuate artery supplies several interlobular arteries that feed into the afferent arterioles that supply the glomeruli.

After filtration occurs the blood moves through a small network of venules that converge into interlobular veins. As with the arteriole distribution the veins follow the same pattern, the interlobular provide blood to the arcuate veins then back to the interlobar veins which come to form the renal vein exiting the kidney for transfusion for blood.

Histology

Renal histology studies the structure of the kidney as viewed under a microscope. Various distinct cell types occur in the kidney, including:

- Kidney glomerulus parietal cell

- Kidney glomerulus podocyte

- Kidney proximal tubule brush border cell

- Loop of Henle thin segment cell

- Thick ascending limb cell

- Kidney distal tubule cell

- Kidney collecting duct cell

- Interstitial kidney cell

Functions

The kidney participates in whole-body homeostasis, regulating acid-base balance, electrolyte concentrations, extracellular fluid volume, and regulation of blood pressure. The kidney accomplishes these homeostatic functions both independently and in concert with other organs, particularly those of the endocrine system. Various endocrine hormones coordinate these endocrine functions; these include renin, angiotensin II, aldosterone, antidiuretic hormone, and atrial natriuretic peptide, among others.

Many of the kidney's functions are accomplished by relatively simple mechanisms of filtration, reabsorption, and secretion, which take place in the nephron. Filtration, which takes place at the renal corpuscle, is the process by which cells and large proteins are filtered from the blood to make an ultrafiltrate that will eventually become urine. Reabsorption is the transport of molecules from this ultrafiltrate and into the blood. Secretion is the reverse process, in which molecules are transported in the opposite direction, from the blood into the urine.

Excretion of wastes

The kidneys excrete a variety of waste products produced by metabolism. These include the nitrogenous wastes urea, from protein catabolism, and uric acid, from nucleic acid metabolism.

Acid-base homeostasis

Two organ systems, the kidneys and lungs, maintain acid-base homeostasis, which is the maintenance of pH around a relatively stable value. The kidneys contribute to acid-base homeostasis by regulating bicarbonate (HCO3-) concentration.

Osmolality regulation

Any significant rise or drop in plasma osmolality is detected by the hypothalamus, which communicates directly with the posterior pituitary gland. A rise in osmolality causes the gland to secrete antidiuretic hormone (ADH), resulting in water reabsorption by the kidney and an increase in urine concentration. The two factors work together to return the plasma osmolality to its normal levels.

ADH binds to principal cells in the collecting duct that translocate aquaporins to the membrane allowing water to leave the normally impermeable membrane and be reabsorbed into the body by the vasa recta, thus increasing the plasma volume of the body.

There are two systems that create a hyperosmotic medulla and thus increase the body plasma volume: Urea recycling and the 'single effect.'

Urea is usually excreted as a waste product from the kidneys. However, when plasma blood volume is low and ADH is released the aquaporins that are opened are also permeable to urea. This allows urea to leave the collecting duct into the medulla creating a hyperosmotic solution that 'attracts' water. Urea can then re-enter the nephron and be excreted or recycled again depending on whether ADH is still present or not.

The 'Single effect' describes the fact that the ascending thick limb of the loop of Henle is not permeable to water but is permeable to NaCl. This means that a countercurrent system is created whereby the medulla becomes increasingly concentrated setting up an osmotic gradient for water to follow should the aquaporins of the collecting duct be opened by ADH.

Blood pressure regulation

Long-term regulation of blood pressure predominantly depends upon the kidney. This primarily occurs through maintenance of the extracellular fluid compartment, the size of which depends on the plasma sodium concentration. Although the kidney cannot directly sense blood pressure, changes in the delivery of sodium and chloride to the distal part of the nephron alter the kidney's secretion of the enzyme renin. When the extracellular fluid compartment is expanded and blood pressure is high, the delivery of these ions is increased and renin secretion is decreased. Similarly, when the extracellular fluid compartment is contracted and blood pressure is low, sodium and chloride delivery is decreased and renin secretion is increased in response.

Renin is the first in a series of important chemical messengers that comprise the renin-angiotensin system. Changes in renin ultimately alter the output of this system, principally the hormones angiotensin II and aldosterone. Each hormone acts via multiple mechanisms, but both increase the kidney's absorption of sodium chloride, thereby expanding the extracellular fluid compartment and raising blood pressure. When renin levels are elevated, the concentrations of angiotensin II and aldosterone increase, leading to increased sodium chloride reabsorption, expansion of the extracellular fluid compartment, and an increase in blood pressure. Conversely, when renin levels are low, angiotensin II and aldosterone levels decrease, contracting the extracellular fluid compartment, and decreasing blood pressure.

Hormone secretion

The kidneys secrete a variety of hormones, including erythropoietin, calcitriol, and renin. Erythropoietin is released in response to hypoxia (low levels of oxygen) in the renal circulation. It stimulates erythropoiesis (production of red blood cells) in the bone marrow. Calcitriol, the activated form of vitamin D, promotes intestinal absorption of calcium and the renal excretion of phosphate. Part of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, renin is an enzyme involved in the regulation of aldosterone levels.

Development

The mammalian kidney develops from intermediate mesoderm. Kidney development, also called nephrogenesis, proceeds through a series of three successive phases, each marked by the development of a more advanced pair of kidneys: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros.[5]

Evolutionary adaptation

Kidneys of various animals show evidence of evolutionary adaptation and have long been studied in ecophysiology and comparative physiology. Kidney morphology, often indexed as the relative medullary thickness, is associated with habitat aridity among species of mammals.[6]

Etymology

Medical terms related to the kidneys commonly use terms such as renal and the prefix nephro-. The adjective renal, meaning related to the kidney, is from the Latin rēnēs, meaning kidneys; the prefix nephro- is from the Ancient Greek word for kidney, nephros (νεφρός).[7] For example, surgical removal of the kidney is a nephrectomy, while a reduction in kidney function is called renal dysfunction.

Diseases and disorders

Congenital

- Congenital hydronephrosis

- Congenital obstruction of urinary tract

- Duplicated ureter

- Horseshoe kidney

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Renal agenesis

- Renal dysplasia

- Unilateral small kidney

- Multicystic dysplastic kidney

Acquired

- Diabetic nephropathy

- Glomerulonephritis

- Hydronephrosis is the enlargement of one or both of the kidneys caused by obstruction of the flow of urine.

- Interstitial nephritis

- Kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) are a relatively common and particularly painful disorder.

- Kidney tumors

- Lupus nephritis

- Minimal change disease

- In nephrotic syndrome, the glomerulus has been damaged so that a large amount of protein in the blood enters the urine. Other frequent features of the nephrotic syndrome include swelling, low serum albumin, and high cholesterol.

- Pyelonephritis is infection of the kidneys and is frequently caused by complication of a urinary tract infection.

- Renal failure

Kidney failure

Generally, humans can live normally with just one or two kidneys, as one has more functioning renal tissue than is needed to survive. Only when the amount of functioning kidney tissue is greatly diminished will chronic kidney disease develop. Renal replacement therapy, in the form of dialysis or kidney transplantation, is indicated when the glomerular filtration rate has fallen very low or if the renal dysfunction leads to severe symptoms.

In other animals

In the majority of vertebrates, the mesonephros persists into the adult, albeit usually fused with the more advanced metanephros; only in amniotes is the mesonephros restricted to the embryo. The kidneys of fish and amphibians are typically narrow, elongated organs, occupying a significant portion of the trunk. The collecting ducts from each cluster of nephrons usually drain into an archinephric duct, which is homologous with the vas deferens of amniotes. However, the situation is not always so simple; in cartilaginous fish and some amphibians, there is also a shorter duct, similar to the amniote ureter, which drains the posterior (metanephric) parts of the kidney, and joins with the archinephric duct at the bladder or cloaca. Indeed, in many cartilaginous fish, the anterior portion of the kidney may degenerate or cease to function altogether in the adult.[8]

In the most primitive vertebrates, the hagfish and lampreys, the kidney is unusually simple: it consists of a row of nephrons, each emptying directly into the archinephric duct. Invertebrates may possess excretory organs that are sometimes referred to as "kidneys", but, even in Amphioxus, these are never homologous with the kidneys of vertebrates, and are more accurately referred to by other names, such as nephridia.[8]

The kidneys of reptiles consist of a number of lobules arranged in a broadly linear pattern. Each lobule contains a single branch of the ureter in its centre, into which the collecting ducts empty. Reptiles have relatively few nephrons compared with other amniotes of a similar size, possibly because of their lower metabolic rate.[8]

Birds have relatively large, elongated kidneys, each of which is divided into three or more distinct lobes. The lobes consists of several small, irregularly arranged, lobules, each centred on a branch of the ureter. Birds have small glomeruli, but about twice as many nephrons as similarly sized mammals.[8]

The human kidney is fairly typical of that of mammals. Distinctive features of the mammalian kidney, in comparison with that of other vertebrates, include the presence of the renal pelvis and renal pyramids, and of a clearly distinguishable cortex and medulla. The latter feature is due to the presence of elongated loops of Henle; these are much shorter in birds, and not truly present in other vertebrates (although the nephron often has a short intermediate segment between the convoluted tubules). It is only in mammals that the kidney takes on its classical "kidney" shape, although there are some exceptions, such as the multilobed reniculate kidneys of cetaceans.[8]

History

The Latin term renes is related to the English word "reins", a synonym for the kidneys in Shakespearean English (eg. Merry Wives of Windsor 3.5), which was also the time the King James Version was translated. Kidneys were once popularly regarded as the seat of the conscience and reflection[9][10], and a number of verses in the Bible (eg. Ps. 7:9, Rev. 2:23) state that God searches out and inspects the kidneys, or "reins", of humans. Similarly, the Talmud (Berakhoth 61.a) states that one of the two kidneys counsels what is good, and the other evil.

Animal kidneys as food

The kidneys of animals can be cooked and eaten by humans (along with other offal).

Kidneys are usually grilled or sautéed, but in more complex dishes they are stewed with a sauce that will improve their flavor. In many preparations kidneys are combined with pieces of meat or liver, like in mixed grill or in Meurav Yerushalmi. Among the most reputed kidney dishes, the British Steak and kidney pie, the Swedish Hökarpanna (pork and kidney stew), the French Rognons de veau sauce moutarde (veal kidneys in mustard sauce) and the Spanish "Riñones al Jerez" (kidneys stewed in sherry sauce), deserve special mention.[11]

See also

References

- ^ Cotran, RS S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Walter F., PhD. Boron (2004). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3.

- ^ http://www.indexedvisuals.com/scripts/ivstock/pic.asp?id=118-100

- ^ http://www.bioportfolio.com/indepth/Kidney.html

- ^ Bruce M. Carlson (2004). Human Embryology and Developmental Biology (3rd edition ed.). Saint Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0-323-03649-X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Al-kahtani, M. A. (2004). "Kidney mass and relative medullary thickness of rodents in relation to habitat, body size, and phylogeny" (PDF). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 77: 346–365.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Maton, Anthea (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 367–376. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics p. 60 by Paul Ramsey, Margaret Farley, Albert Jonsen, William F. May (2002)

- ^ History of Nephrology 2 p. 235 by International Association for the History of Nephrology Congress, Garabed Eknoyan, Spyros G. Marketos, Natale G. De Santo - 1997; Reprint of American Journal of Nephrology; v. 14, no. 4-6, 1994.

- ^ Rognons dans les recettes Template:Fr

External links

- electron microscopic images of the kidney (Dr. Jastrow's EM-Atlas)

- European Renal Genome project kidney function tutorial

- Kidney Foundation of Canada kidney disease information

- National Kidney Foundation

- Kidney Foundation (Canada)

- BC Renal Agency - Official site for the province-wide network of renal care providers in British Columbia, Canada

- World Kidney Day website

- UNC Nephropathology

- American Society of Nephrology

- American Kidney Fund

- Renal Fellow Network: Structure & Function of Other Animals' Kidneys