Alchemy: Difference between revisions

→History: also Babylonia |

→History: Alkindus was not Persian, while Geber's ethnicity is unclear |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

The origins of Western alchemy are traceable back to [[ancient Egypt]].<ref>[[Erich Neumann (psychologist)|Neumann, Erich]]. ''The origins and history of consciousness'', with a foreword by C.G. Jung. Translated from the German by R.F.C. Hull. New York : Pantheon Books, 1954. Confer p.255, footnote 76: "''Since Alchemy actually originated in Egypt, it is not improbable that esoteric interpretations of the Osiris myth are among the foundations of the art ...''"</ref> The [[s:Leyden papyrus X|Leyden papyrus X]] and the [[Stockholm papyrus]] along with the [[Greek magical papyri]] comprise the first "book" on alchemy still existent. [[Babylonia]]n,<ref>{{citation|title=A consideration of Babylonian astronomy within the historiography of science|author=Francesca Rochberg|journal=Studies In History and Philosophy of Science|volume=33|issue=4|date=December 2002|pages=661-684|doi=10.1016/S0039-3681(02)00022-5}}</ref> Greek and [[Indian philosophy|Indian philosophers]] theorized that there were only four [[classical element]]s (rather than today's 117 [[chemical element]]s, a useful analogy is with the highly similar [[state of matter|states of matter]]); Earth, Fire, Water, and Air. The Greek philosophers, in order to prove their point, burned a log: The log was the earth, the flames burning it was fire, the smoke being released was air, and the smoldering soot at the bottom was bubbling water. Because of this, the belief that these four "elements" were at the heart of everything soon spread, only later being replaced in the [[Middle Ages]] by [[Geber]]'s theory of seven elements, which was then replaced by the modern theory of chemical elements during the [[early modern period]]. |

The origins of Western alchemy are traceable back to [[ancient Egypt]].<ref>[[Erich Neumann (psychologist)|Neumann, Erich]]. ''The origins and history of consciousness'', with a foreword by C.G. Jung. Translated from the German by R.F.C. Hull. New York : Pantheon Books, 1954. Confer p.255, footnote 76: "''Since Alchemy actually originated in Egypt, it is not improbable that esoteric interpretations of the Osiris myth are among the foundations of the art ...''"</ref> The [[s:Leyden papyrus X|Leyden papyrus X]] and the [[Stockholm papyrus]] along with the [[Greek magical papyri]] comprise the first "book" on alchemy still existent. [[Babylonia]]n,<ref>{{citation|title=A consideration of Babylonian astronomy within the historiography of science|author=Francesca Rochberg|journal=Studies In History and Philosophy of Science|volume=33|issue=4|date=December 2002|pages=661-684|doi=10.1016/S0039-3681(02)00022-5}}</ref> Greek and [[Indian philosophy|Indian philosophers]] theorized that there were only four [[classical element]]s (rather than today's 117 [[chemical element]]s, a useful analogy is with the highly similar [[state of matter|states of matter]]); Earth, Fire, Water, and Air. The Greek philosophers, in order to prove their point, burned a log: The log was the earth, the flames burning it was fire, the smoke being released was air, and the smoldering soot at the bottom was bubbling water. Because of this, the belief that these four "elements" were at the heart of everything soon spread, only later being replaced in the [[Middle Ages]] by [[Geber]]'s theory of seven elements, which was then replaced by the modern theory of chemical elements during the [[early modern period]]. |

||

Alchemy encompasses several philosophical traditions spanning four millennia and three continents. These traditions' general penchant for cryptic and symbolic language makes it hard to trace their mutual influences and "genetic" relationships. Alchemy starts becoming much clearer in the 8th century with the works of the [[ |

Alchemy encompasses several philosophical traditions spanning four millennia and three continents. These traditions' general penchant for cryptic and symbolic language makes it hard to trace their mutual influences and "genetic" relationships. Alchemy starts becoming much clearer in the 8th century with the works of the [[Alchemy and chemistry in medieval Islam|Islamic alchemist]], [[Geber|Jabir ibn Hayyan]] (known as "Geber" in Europe), who introduced a [[Scientific method|methodical]] and [[experiment]]al approach to scientific research based in the [[laboratory]], in contrast to the ancient Greek and Egyptian alchemists whose works were mainly allegorical.<ref name=Kraus>Kraus, Paul, Jâbir ibn Hayyân, ''Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque,''. Cairo (1942–1943). Repr. By Fuat Sezgin, (Natural Sciences in Islam. 67-68), Frankfurt. 2002: |

||

{{quote|“To form an idea of the historical place of Jabir’s alchemy and to tackle the problem of its sources, it is advisable to compare it with what remains to us of the alchemical literature in the [[Greek language]]. One knows in which miserable state this literature reached us. Collected by [[Byzantine science|Byzantine scientists]] from the tenth century, the corpus of the Greek alchemists is a cluster of incoherent fragments, going back to all the times since the third century until the end of the Middle Ages.”}} |

{{quote|“To form an idea of the historical place of Jabir’s alchemy and to tackle the problem of its sources, it is advisable to compare it with what remains to us of the alchemical literature in the [[Greek language]]. One knows in which miserable state this literature reached us. Collected by [[Byzantine science|Byzantine scientists]] from the tenth century, the corpus of the Greek alchemists is a cluster of incoherent fragments, going back to all the times since the third century until the end of the Middle Ages.”}} |

||

{{quote|“The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers, among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz , von Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugiere and others, could make clear only few points of detail...}} |

{{quote|“The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers, among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz , von Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugiere and others, could make clear only few points of detail...}} |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

([[cf.]] {{cite web |author=[[Ahmad Y Hassan]] |title=A Critical Reassessment of the Geber Problem: Part Three |url=http://www.history-science-technology.com/Geber/Geber%203.htm |accessdate=2008-08-09}})</ref> |

([[cf.]] {{cite web |author=[[Ahmad Y Hassan]] |title=A Critical Reassessment of the Geber Problem: Part Three |url=http://www.history-science-technology.com/Geber/Geber%203.htm |accessdate=2008-08-09}})</ref> |

||

Other famous alchemists include [[Rhazes]], [[Avicenna]] and [[Ahmad Ibn Imad ul-din|Imad ul-din]] in |

Other famous alchemists include [[Rhazes]], [[Avicenna]] and [[Ahmad Ibn Imad ul-din|Imad ul-din]] in Persia; [[Wei Boyang]] in [[Chinese alchemy]]; and [[Nagarjuna (metallurgist)|Nagarjuna]] in [[History of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent|Indian alchemy]]; and [[Albertus Magnus]] and [[Pseudo-Geber]] in European alchemy; as well as the anonymous author of the ''[[Mutus Liber]]'', published in France in the late 17th century, which was a 'wordless book' that claimed to be a guide to making the [[philosopher's stone]], using a series of 15 symbols and illustrations. The philosopher's stone was an object that was thought to be able to amplify one's power in alchemy and, if possible, grant the user ageless immortality, unless he fell victim to burnings or drowning; the common belief was that fire and water were the two greater elements that were implemented into the creation of the stone. |

||

In the case of the Chinese and European alchemists, there was a difference between the two. The European alchemists tried to transmute lead into gold, and, no matter how futile or toxic the element, would continue trying until it was royally outlawed later into the century. The Chinese, however, paid no heed to the philosopher's stone or transmutation of lead to gold; they focused more on medicine for the greater good. During Enlightenment, these "elixirs" were a strong cure for sicknesses, unless it was a test medicine. In general, most tests were fatal, but stabilized elixirs served great purposes. On the other hand, the |

In the case of the Chinese and European alchemists, there was a difference between the two. The European alchemists tried to transmute lead into gold, and, no matter how futile or toxic the element, would continue trying until it was royally outlawed later into the century. The Chinese, however, paid no heed to the philosopher's stone or transmutation of lead to gold; they focused more on medicine for the greater good. During Enlightenment, these "elixirs" were a strong cure for sicknesses, unless it was a test medicine. In general, most tests were fatal, but stabilized elixirs served great purposes. On the other hand, the Islamic alchemists were interested in alchemy for a variety of reasons, whether it was for the transmutation of metals or [[Takwin|artificial creation of life]], or for practical uses [[Medicine in medieval Islam|such as medicine]]. |

||

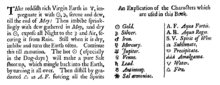

[[Image:Alchemy-Digby-RareSecrets.png|thumb|right|Extract and symbol key from a 17th-century book on alchemy. The symbols used have a [[Bijection|one-to-one correspondence]] with symbols used in [[astrology]] at the time.]] |

[[Image:Alchemy-Digby-RareSecrets.png|thumb|right|Extract and symbol key from a 17th-century book on alchemy. The symbols used have a [[Bijection|one-to-one correspondence]] with symbols used in [[astrology]] at the time.]] |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

#Greek alchemy [332 BC – 642 AD], studied at the [[Library of Alexandria]] [[Stockholm papyrus]] |

#Greek alchemy [332 BC – 642 AD], studied at the [[Library of Alexandria]] [[Stockholm papyrus]] |

||

#[[Chinese alchemy]] [142 AD], [[Wei Boyang]] writes ''[[The Kinship of the Three]]'' |

#[[Chinese alchemy]] [142 AD], [[Wei Boyang]] writes ''[[The Kinship of the Three]]'' |

||

#[[Alchemy and chemistry in Islam|Islamic alchemy]] [700 – 1400], [[ |

#[[Alchemy and chemistry in medieval Islam|Islamic alchemy]] [700 – 1400], [[Geber]] and his successors were at the forefront of alchemy during the [[Islamic Golden Age]] |

||

#[[Alchemy and chemistry in Islam| |

#[[Alchemy and chemistry in medieval Islam|Islamic chemistry]] [800 – Present], [[Al-Kindi|Alkindus]] and [[Avicenna]] refute transmutation, [[Rhazes]] refutes four [[classical element]]s, and [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī|Tusi]] discovers [[conservation of mass]] |

||

#European alchemy [1300 – Present], Saint [[Albertus Magnus]] builds on Persian alchemy |

#European alchemy [1300 – Present], Saint [[Albertus Magnus]] builds on Persian alchemy |

||

#European chemistry [1661 – Present], [[Robert Boyle|Boyle]] writes ''The Sceptical Chymist'', [[Antoine Lavoisier|Lavoisier]] writes ''[[Traité Élémentaire de Chimie]] (Elements of Chemistry)'', and [[John Dalton|Dalton]] publishes his ''Atomic Theory'' |

#European chemistry [1661 – Present], [[Robert Boyle|Boyle]] writes ''The Sceptical Chymist'', [[Antoine Lavoisier|Lavoisier]] writes ''[[Traité Élémentaire de Chimie]] (Elements of Chemistry)'', and [[John Dalton|Dalton]] publishes his ''Atomic Theory'' |

||

Revision as of 17:29, 13 March 2010

Alchemy, originally derived from the Ancient Greek word khemia (Χημία) meaning "art of transmuting metals", later arabicized as al-kimia (الكيمياء), is both a philosophy and an ancient practice focused on the attempt to change base metals into gold, investigating the preparation of the "elixir of longevity", and achieving ultimate wisdom, involving the improvement of the alchemist as well as the making of several substances described as possessing unusual properties.[1] The practical aspect of alchemy generated the basics of modern inorganic chemistry, namely concerning procedures, equipment and the identification and use of many current substances.

Alchemy has been practiced in Mesopotamia (comprising much of today's Iraq), Egypt, Persia (today's Iran), India, China, Japan, Korea and in Classical Greece and Rome, in the Post-Islamic Persia, and then in Europe up to the 20th century, in a complex network of schools and philosophical systems spanning at least 2500 years.

Etymology

The word alchemy derives in turn from the Old French alkemie; from the Medieval Latin alchimia; from the Arabic al-kimia (الكيمياء); and ultimately from the Ancient Greek khemia (Χημία) meaning "art of transmuting metals".[2]

During the seventeenth century chemistry as a separate science was derived from Alchemy[citation needed] , with the work of Robert Boyle, sometimes known as "The father of Chemistry",[3] who in his book "The Skeptical Chymist" attacked Paracelsus and the old Aristotelian concepts of the elements and laid down the foundations of modern chemistry.

Alchemy as a philosophical and spiritual discipline

Alchemy became known as the spagyric art after Greek words meaning to separate and to join together in the 16th century, the word probably being coined by Paracelsus. Compare this with one of the dictums of Alchemy in Latin: Solve et Coagula — Separate, and Join Together (or "dissolve and coagulate").[4]

The best-known goals of the alchemists were the transmutation of common metals into gold (called chrysopoeia) or silver (less well known is plant alchemy, or "spagyric"); the creation of a "panacea", or the elixir of life, a remedy that, it was supposed, would cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely; and the discovery of a universal solvent.[5] Although these were not the only uses for the discipline, they were the ones most documented and well-known. Certain Hermetic schools argue that the transmutation of lead into gold is analogical for the transmutation of the physical body (Saturn or lead) into (Gold) with the goal of attaining immortality.[6] This is described as Internal Alchemy. Starting with the Middle Ages, Persian and European alchemists invested much effort in the search for the "philosopher's stone", a legendary substance that was believed to be an essential ingredient for either or both of those goals. Pope John XXII issued a bull against alchemical counterfeiting, and the Cistercians banned the practice amongst their members. In 1403, Henry IV of England banned the practice of Alchemy. In the late 14th century, Piers the Ploughman and Chaucer both painted unflattering pictures of Alchemists as thieves and liars. By contrast, Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, in the late 16th century, sponsored various alchemists in their work at his court in Prague.

It is a popular belief that Alchemists made mundane contributions to the "chemical" industries of the day—ore testing and refining, metalworking, production of gunpowder, ink, dyes, paints, cosmetics, leather tanning, ceramics, glass manufacture, preparation of extracts, liquors, and so on (it seems that the preparation of aqua vitae, the "water of life", was a fairly popular "experiment" among European alchemists). In reality, although Alchemists contributed distillation to Western Europe, they did little for any known industry. Long before Alchemists appeared, goldsmiths knew how to tell what was good gold or fake, and industrial technology grew by the work of the artisans themselves, rather than any Alchemical helpers.[citation needed]

The double origin of Alchemy in Greek philosophy as well as in Egyptian and Mesopotamian technology set, from the start, a double approach: the technological, operative one, which Marie-Louise von Franz call extravert, and the mystic, contemplative, psychological one, which von Franz names as introvert. These are not mutually exclusive, but complementary instead, as meditation requires practice in the real world, and conversely.[7]

Several early alchemists, such as Zosimos of Panopolis, are recorded as viewing alchemy as a spiritual discipline, and, in the Middle Ages, metaphysical aspects, substances, physical states, and molecular material processes as mere metaphors for spiritual entities, spiritual states, and, ultimately, transformations. In this sense, the literal meanings of 'Alchemical Formulas' were a blind, hiding their true spiritual philosophy, which being at odds with the Medieval Christian Church was a necessity that could have otherwise led them to the "stake and rack" of the Inquisition under charges of heresy.[8] Thus, both the transmutation of common metals into gold and the universal panacea symbolized evolution from an imperfect, diseased, corruptible, and ephemeral state towards a perfect, healthy, incorruptible, and everlasting state; and the philosopher's stone then represented a mystic key that would make this evolution possible. Applied to the alchemist himself, the twin goal symbolized his evolution from ignorance to enlightenment, and the stone represented a hidden spiritual truth or power that would lead to that goal. In texts that are written according to this view, the cryptic alchemical symbols, diagrams, and textual imagery of late alchemical works typically contain multiple layers of meanings, allegories, and references to other equally cryptic works; and must be laboriously "decoded" in order to discover their true meaning.

In his Alchemical Catechism, Paracelsus clearly denotes that his usage of the metals was a symbol:

Q. When the Philosophers speak of gold and silver, from which they extract their matter, are we to suppose that they refer to the vulgar gold and silver? A. By no means; vulgar silver and gold are dead, while those of the Philosophers are full of life.[9]

Psychology

Alchemical symbolism has been occasionally used by psychologists and philosophers. Carl Jung reexamined alchemical symbolism and theory and began to show the inner meaning of alchemical work as a spiritual path.[10][11] Alchemical philosophy, symbols and methods have enjoyed something of a renaissance in post-modern contexts.[citation needed]

Jung saw alchemy as a Western proto-psychology dedicated to the achievement of individuation.[10] In his interpretation, alchemy was the vessel by which Gnosticism survived its various purges into the Renaissance,[12] a concept also followed by others such as Stephan A. Hoeller. In this sense, Jung viewed alchemy as comparable to a Yoga of the East, and more adequate to the Western mind than Eastern religions and philosophies. The practice of Alchemy seemed to change the mind and spirit of the Alchemist. Conversely, spontaneous changes on the mind of Western people undergoing any important stage in individuation seems to produce, on occasion, imagery known to Alchemy and relevant to the person's situation.[13]

His interpretation of Chinese alchemical texts in terms of his analytical psychology also served the function of comparing Eastern and Western alchemical imagery and core concepts and hence its possible inner sources (archetypes).[14][15]

Marie-Louise von Franz, a disciple of Jung, continued Jung's studies on Alchemy and its psychological meaning.

Magnum opus

The Great Work; mystic interpretation of its four stages:[16]

- nigredo (-putrefactio), blackening (-putrefaction): corruption, dissolution, individuation, see also Suns in alchemy - Sol Niger

- albedo, whitening: purification, burnout of impurity; the moon, female

- citrinitas, yellowing: spiritualisation, enlightenment; the sun, male;

- rubedo, reddening: unification of man with god, unification of the limited with the unlimited.

After the 15th century, many writers tended to compress citrinitas into rubedo and consider only three stages.[17]

However, it is in citrinitas that the Chemical Wedding takes place, generating the Philosophical Mercury without which the Philosopher's Stone, triumph of the Work, could never be accomplished.[18]

Within the Magnum Opus was the creation of the Sanctum Moleculae, that is the 'Sacred Masses' that were derived from the Sacrum Particulae, that is the 'Sacred Particles', needed to complete the process of achieving the Magnum Opus.[citation needed]

Alchemy as a subject of historical research

The history of alchemy has become a vigorous academic field. As the obscure hermetic language of the alchemists is gradually being "deciphered", historians are becoming more aware of the intellectual connections between that discipline and other facets of Western cultural history, such as the sociology and psychology of the intellectual communities, kabbalism, spiritualism, Rosicrucianism, and other mystic movements, cryptography, witchcraft, and the evolution of science and philosophy.

History

In a historical sense, Alchemy is the pursuit of transforming common metals into valuable gold. According to Marie-Louise von Franz, the initial basis for alchemy were Egyptian metal technology and mummification, Mesopotamian technology and astrology, and Pre-Socratic Greek philosophers such as Empedocles, Thales of Miletus and Heraclitus.[7]

The origins of Western alchemy are traceable back to ancient Egypt.[19] The Leyden papyrus X and the Stockholm papyrus along with the Greek magical papyri comprise the first "book" on alchemy still existent. Babylonian,[20] Greek and Indian philosophers theorized that there were only four classical elements (rather than today's 117 chemical elements, a useful analogy is with the highly similar states of matter); Earth, Fire, Water, and Air. The Greek philosophers, in order to prove their point, burned a log: The log was the earth, the flames burning it was fire, the smoke being released was air, and the smoldering soot at the bottom was bubbling water. Because of this, the belief that these four "elements" were at the heart of everything soon spread, only later being replaced in the Middle Ages by Geber's theory of seven elements, which was then replaced by the modern theory of chemical elements during the early modern period.

Alchemy encompasses several philosophical traditions spanning four millennia and three continents. These traditions' general penchant for cryptic and symbolic language makes it hard to trace their mutual influences and "genetic" relationships. Alchemy starts becoming much clearer in the 8th century with the works of the Islamic alchemist, Jabir ibn Hayyan (known as "Geber" in Europe), who introduced a methodical and experimental approach to scientific research based in the laboratory, in contrast to the ancient Greek and Egyptian alchemists whose works were mainly allegorical.[21]

Other famous alchemists include Rhazes, Avicenna and Imad ul-din in Persia; Wei Boyang in Chinese alchemy; and Nagarjuna in Indian alchemy; and Albertus Magnus and Pseudo-Geber in European alchemy; as well as the anonymous author of the Mutus Liber, published in France in the late 17th century, which was a 'wordless book' that claimed to be a guide to making the philosopher's stone, using a series of 15 symbols and illustrations. The philosopher's stone was an object that was thought to be able to amplify one's power in alchemy and, if possible, grant the user ageless immortality, unless he fell victim to burnings or drowning; the common belief was that fire and water were the two greater elements that were implemented into the creation of the stone.

In the case of the Chinese and European alchemists, there was a difference between the two. The European alchemists tried to transmute lead into gold, and, no matter how futile or toxic the element, would continue trying until it was royally outlawed later into the century. The Chinese, however, paid no heed to the philosopher's stone or transmutation of lead to gold; they focused more on medicine for the greater good. During Enlightenment, these "elixirs" were a strong cure for sicknesses, unless it was a test medicine. In general, most tests were fatal, but stabilized elixirs served great purposes. On the other hand, the Islamic alchemists were interested in alchemy for a variety of reasons, whether it was for the transmutation of metals or artificial creation of life, or for practical uses such as medicine.

A tentative outline is as follows:

- Egyptian alchemy [5000 BC – 400 BC], beginning of alchemy

- Indian alchemy [1200 BC – Present],[22] related to Indian metallurgy; Nagarjuna was an important alchemist

- Greek alchemy [332 BC – 642 AD], studied at the Library of Alexandria Stockholm papyrus

- Chinese alchemy [142 AD], Wei Boyang writes The Kinship of the Three

- Islamic alchemy [700 – 1400], Geber and his successors were at the forefront of alchemy during the Islamic Golden Age

- Islamic chemistry [800 – Present], Alkindus and Avicenna refute transmutation, Rhazes refutes four classical elements, and Tusi discovers conservation of mass

- European alchemy [1300 – Present], Saint Albertus Magnus builds on Persian alchemy

- European chemistry [1661 – Present], Boyle writes The Sceptical Chymist, Lavoisier writes Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elements of Chemistry), and Dalton publishes his Atomic Theory

Modern connections to alchemy

Persian alchemy was a forerunner of modern scientific chemistry. Alchemists used many of the same laboratory tools that are used today. These tools were not usually sturdy or in good condition, especially during the medieval period of Europe. Many transmutation attempts failed when alchemists unwittingly made unstable chemicals. This was made worse by the unsafe conditions in which the alchemists worked.

Up to the 16th century, alchemy was considered serious science in Europe; for instance, Isaac Newton devoted considerably more of his writing to the study of alchemy (see Isaac Newton's occult studies) than he did to either optics or physics, for which he is famous. Other eminent alchemists of the Western world are Roger Bacon, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Tycho Brahe, Thomas Browne, and Parmigianino. The decline of alchemy began in the 18th century with the birth of modern chemistry, which provided a more precise and reliable framework for matter transmutations and medicine, within a new grand design of the universe based on rational materialism.

Alchemy in traditional medicine

Traditional medicines involve transmutation by alchemy, using pharmacological or a combination of pharmacological and spiritual techniques. In Chinese medicine the alchemical traditions of pao zhi will transform the nature of the temperature, taste, body part accessed or toxicity. In Ayurveda the samskaras are used to transform heavy metals and toxic herbs in a way that removes their toxicity. These processes are actively used to the present day.[23]

Nuclear transmutation

In 1919, Ernest Rutherford used artificial disintegration to convert nitrogen into oxygen.[24] From then on, this sort of scientific transmutation has been routinely performed in many nuclear physics-related laboratories and facilities, like particle accelerators, nuclear power stations and nuclear weapons as a by-product of fission and other physical processes.

In literature

A play by Ben Jonson, The Alchemist, is a satirical and skeptical take on the subject.

Part 2 of Goethe's Faust, is full of alchemical symbolism.[25]

According to Hermetic Fictions: Alchemy and Irony in the Novel (Keele University Press, 1995), by David Meakin, alchemy is also featured in such novels and poems as those by William Godwin, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Emile Zola, Jules Verne, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, James Joyce, Gustav Meyrink, Lindsay Clarke, Marguerite Yourcenar, Umberto Eco, Michel Butor, Paulo Coelho, Amanda Quick, Gabriel García Marquez and Maria Szepes.

Hilary Mantel, in her novel Fludd (1989, Penguin), mentions the spagyric art. 'After separation, drying out, moistening, dissolving, coagulating, fermenting, comes purification, recombination: the creation of substances the world until now has never beheld. This is the opus contra naturem, this is the spagyric art, this is the Alchymical Wedding'. (page 79)

In Dante's Inferno, it is placed within the Tenth ring of the 8th circle.[26]

In Angie Sage's Septimus Heap series, Marcellus Pye is an important Alchemist that first appears in Physik, the third book.

In The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel series, one of the main characters is a alchemist.

The manga and anime series Fullmetal Alchemist bases itself of a more fantasised version of alchemy.

In contemporary art

In the twentieth century alchemy was a profoundly important source of inspiration for the Surrealist artist Max Ernst, who used the symbolism of alchemy to inform and guide his work. M.E. Warlick wrote his Max Ernst and Alchemy describing this relationship in detail.

Contemporary artists use alchemy as inspiring subject matter, like Odd Nerdrum, whose interest has been noted by Richard Vine, and the painter Michael Pearce,[27] whose interest in alchemy dominates his work. His works Fama[28] and The Aviator's Dream[29] particularly express alchemical ideas in a painted allegory.

See also

Other alchemical pages

- Alchemical symbol

- Alchemy in art and entertainment

- Alchemy in history

- Alembic

- Alkahest

- Astrology and alchemy

- Berith

- Jakob Boehme

- Circle with a point at its centre

- Elixir of life

- Emerald Tablet

- Robert Fludd

- Four Humors

- Hermeticism

- Homunculus

- Michael Maier

- Musaeum Hermeticum

- Paracelsus

- Philosopher's stone

- Quintessence

- Herbert Silberer

- Vulcan of the alchemists

- Monas Hieroglyphica

- Frater Albertus

Alchemy and psychoanalysis

Other resources

| class="col-break " |

Related and alternative philosophies

- Western mystery tradition

- Internal alchemy

- Astrology

- Necromancy, magic, magick

- Esotericism, Rosicrucianism, Illuminati

- Taoism and the Five Elements

- Asemic writing

- Kayaku-Jutsu

- Acupuncture, moxibustion, ayurveda, homeopathy

- Anthroposophy

- Psychology and Carl Jung

- New Age

- Tay al-Ard

- Yoga Nidra

Substances of the alchemists

- lead • tin • iron • copper • mercury • silver • gold

- phosphorus • sulfur (sulphur) • arsenic • antimony

- vitriol • quartz • cinnabar • pyrites • orpiment • galena

- magnesia • lime • potash • natron • saltpetre • kohl

- ammonia • ammonium chloride • alcohol • camphor

- sulfuric acid (sulphuric acid) • hydrochloric acid • nitric acid • acetic acid • formic acid • citric acid • tartaric acid

- aqua regia • gunpowder

- carmot

- blue vitriol • vinegar • salt

Scientific connections

- Chemistry

- Cupellation

- Physics

- Synthesis of noble metals

- Nuclear transmutation

- Scientific method

- Protoscience and Pseudoscience

- Obsolete scientific theories

- Historicism

- Erosion

Notes

- ^ alchemy: Definition from Answers.com. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. Alchemy, accessed 10 Feb 2010.

- ^ Deem, Rich (2005). "The Religious Affiliation of Robert Boyle the father of modern chemistry. From: Famous Scientists Who Believed in God". adherents.com. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ Davis, Erik. "The Gods of the Funny Books: An Interview with Neil Gaiman and Rachel Pollack". Gnosis (magazine). Techgnosis (reprint from Summer 1994 issue). Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- ^ Alchemy at Dictionary.com.

- ^ The True Nature of Hermetic Alchemy.

- ^ a b von Franz, M-L. Alchemical Active Imagination. Shambala. Boston. 1997. ISBN 0-87773-589-1.

- ^ Blavatsky, H.P. (1888). [[The Secret Doctrine]]. Vol. ii. Theosophical Publishing Company. 238. ISBN 978-1557000026.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Paracelsus. "Alchemical Catechism". Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ a b Jung, C. G. (1944). Psychology and Alchemy (2nd ed. 1968 Collected Works Vol. 12 ISBN 0-691-01831-6). London: Routledge.

- ^ Jung, C. G., & Hinkle, B. M. (1912). Psychology of the Unconscious : a study of the transformations and symbolisms of the libido, a contribution to the history of the evolution of thought. London: Kegan Paul Trench Trubner. (revised in 1952 as Symbols of Transformation, Collected Works Vol.5 ISBN 0-691-01815-4).

- ^ Jung, C. G., & Jaffe A. (1962). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. London: Collins. This is Jung's autobiography, recorded and edited by Aniela Jaffe, ISBN 0-679-72395-1.

- ^ Jung, C. G. - Psychology and Alchemy; Symbols of Transformation.

- ^ C.-G. Jung Preface to Richard Wilhelm's translation of the I Ching.

- ^ C.-G. Jung Preface to the translation of The Secret of The Golden Flower.

- ^ The-Four-Stages-of-Alchemical-Work.

- ^ Meyrink und das theomorphische Menschenbild.

- ^ The order for the Opus phases is seldom given as constant. Dorn, for instance, in the Theatrum Chemicum, places the citrinitas, the golden color, as the final stage, after the rubedo.

- ^ Neumann, Erich. The origins and history of consciousness, with a foreword by C.G. Jung. Translated from the German by R.F.C. Hull. New York : Pantheon Books, 1954. Confer p.255, footnote 76: "Since Alchemy actually originated in Egypt, it is not improbable that esoteric interpretations of the Osiris myth are among the foundations of the art ..."

- ^ Francesca Rochberg (December 2002), "A consideration of Babylonian astronomy within the historiography of science", Studies In History and Philosophy of Science, 33 (4): 661–684, doi:10.1016/S0039-3681(02)00022-5

- ^ Kraus, Paul, Jâbir ibn Hayyân, Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque,. Cairo (1942–1943). Repr. By Fuat Sezgin, (Natural Sciences in Islam. 67-68), Frankfurt. 2002:

“To form an idea of the historical place of Jabir’s alchemy and to tackle the problem of its sources, it is advisable to compare it with what remains to us of the alchemical literature in the Greek language. One knows in which miserable state this literature reached us. Collected by Byzantine scientists from the tenth century, the corpus of the Greek alchemists is a cluster of incoherent fragments, going back to all the times since the third century until the end of the Middle Ages.”

“The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers, among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz , von Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugiere and others, could make clear only few points of detail...

The study of the Greek alchemists is not very encouraging. An even surface examination of the Greek texts shows that a very small part only was organized according to true experiments of laboratory: even the supposedly technical writings, in the state where we find them today, are unintelligible nonsense which refuses any interpretation.

It is different with Jabir’s alchemy. The relatively clear description of the processes and the alchemical apparatuses, the methodical classification of the substances, mark an experimental spirit which is extremely far away from the weird and odd esotericism of the Greek texts. The theory on which Jabir supports his operations is one of clearness and of an impressive unity. In vain one would seek in the Greek texts a work as systematic as that which is presented for example in the Book of Seventy.”

(cf. Ahmad Y Hassan. "A Critical Reassessment of the Geber Problem: Part Three". Retrieved 2008-08-09.)

- ^ "The oldest Indian writings, the Vedas (Hindu sacred scriptures), contain the same hints of alchemy" - Multhauf, Robert P. & Gilbert, Robert Andrew (2008). Alchemy. Encyclopædia Britannica (2008).

- ^ Junius, Manfred M; The Practical Handbook of Plant Alchemy: An Herbalist's Guide to Preparing Medicinal Essences, Tinctures, and Elixirs; Healing Arts Press 1985.

- ^ Amsco School Publications. "Reviewing Physics: The Physical Setting" (pdf). Amsco School Publications.

"The first artificial transmutation of one or more elements to another was performed by Rutherford in 1919. Rutherford bombarded nitrogen with energetic alpha particles that were moving fast enough to overcome the electric repulsion between themselves and the target nuclei. The alpha particles collided with, and were absorbed by, the nitrogen nuclei, and protons were ejected. In the process oxygen and hydrogen nuclei were created.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink= - ^ see Alice Raphael: Goethe and the Philosopher's Stone, symbolical patterns in 'The Parable' and the second part of 'Faust', London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965.

- ^ Dante's Divine Comedy, Inferno, Canto 29, hosted on the Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ Cal Lutheran | Department of Art - Faculty.

- ^ The Gilded Raven Blog + » fama.

- ^ The Gilded Raven Blog + » Storm / The Aviator’s Dream.

References

- Cavendish, Richard, The Black Arts, Perigee Books

- Gettgins, Fred (1986). Encyclopedia of the Occult. London: Rider.

- Greenberg, Adele Droblas (2000). Chemical History Tour, Picturing Chemistry from Alchemy to Modern Molecular Science. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-35408-2.

- Hart-Davis, Adam (2003). Why does a ball bounce? 101 Questions that you never thought of asking. New York: Firefly Books.

- Hughes, Jonathan (2002). Arthurian Myths and Alcheny, the Kingship of Edward IV. Stroud: Sutton.

- Marius (1976). On the Elements. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02856-2. Trans. Richard Dales.

- Thorndike, Lynn (1923–1958). A History of Magic and Experimental Science. New York: Macmillan.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - Weaver, Jefferson Hane (1987). The World of Physics. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Zumdahl, Steven S. (1989). Chemistry (2nd ed.). Lexington, Maryland: D.C. Heath and Company. ISBN 0-669-16708-8.

- Halleux, R., Les textes alchimiques, Brepols Publishers, 1979, ISBN 978-2-503-36032-4

External links

- Etymology of "alchemy"

- Hidden Symbolism of Alchemy and the Occult Arts by Herbert Silberer

- The Alchemy website - Alchemy from a metaphysical perspective.

- The al-kemi.org website - Alchemy from a spiritual/philosophical perspective.

- Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry

- Alchemy images

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Alchemy

- Antiquity, Vol. 77 (2003) - "A 16th century lab in a 21st century lab".

- The Story of Alchemy and the Beginnings of Chemistry, Muir, M. M. Pattison (1913)

- "Transforming the Alchemists", New York Times, August 1, 2006. Historical revisionism and alchemy.

- Electronic library with hundreds of alchemical books (15th- and 20th century) and 160 original manuscripts.

- The Chymistry of Isaac Newton - A scholarly site devoted to the alchemical, or chymical, writings of Isaac Newton.

- Rex Research - Numerous online alchemical texts.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA