Phrenology: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 198.188.143.117 (talk) to last revision by 71.179.87.73 (HG) |

Unsourced and incorrectly dated anecdote about Lloyd-George and C.P. Snow removed (see talk page) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

The American brothers [[Lorenzo Niles Fowler]] (1811-1896) and [[Orson Squire Fowler]] (1809-1887) were leading phrenologists of their time. Orson, together with associates [[Samuel Wells]] and [[Nelson Sizer]], ran the phrenological business and publishing house ''Fowlers & Wells'' in [[New York City]]. Meanwhile, Lorenzo spent much of his life in England where he initiated the famous phrenological publishing house, L.N Fowler & Co., and gained considerable fame with his ''phrenology head'' (a [[porcelain|china]] head showing the phrenological faculties), which has become a symbol of the discipline. |

The American brothers [[Lorenzo Niles Fowler]] (1811-1896) and [[Orson Squire Fowler]] (1809-1887) were leading phrenologists of their time. Orson, together with associates [[Samuel Wells]] and [[Nelson Sizer]], ran the phrenological business and publishing house ''Fowlers & Wells'' in [[New York City]]. Meanwhile, Lorenzo spent much of his life in England where he initiated the famous phrenological publishing house, L.N Fowler & Co., and gained considerable fame with his ''phrenology head'' (a [[porcelain|china]] head showing the phrenological faculties), which has become a symbol of the discipline. |

||

[[Image:Phrenology-journal.jpg|thumbnail|250px|right|1848 edition of American Phrenological Journal published by Fowlers & Wells, New York City.]]In the [[Victorian era|Victorian age]], phrenology as a psychology was taken seriously and permeated the literature and novels of the day. Many prominent public figures such as the [[Henry Ward Beecher|Reverend Henry Ward Beecher]] (a college classmate and initial partner of Orson Fowler) promoted phrenology actively as a source of psychological insight and self-knowledge. |

[[Image:Phrenology-journal.jpg|thumbnail|250px|right|1848 edition of American Phrenological Journal published by Fowlers & Wells, New York City.]]In the [[Victorian era|Victorian age]], phrenology as a psychology was taken seriously and permeated the literature and novels of the day. Many prominent public figures such as the [[Henry Ward Beecher|Reverend Henry Ward Beecher]] (a college classmate and initial partner of Orson Fowler) promoted phrenology actively as a source of psychological insight and self-knowledge. Thousands of people consulted phrenologists for advice in various matters, such as hiring personnel or finding suitable marriage partners. As such, phrenology as a brain science waned but developed into the popular psychology of the 19th century and functioned in approximately the same way as psychoanalysis permeated social thought and relationships a century later. Beginning during the 1840s, phrenology in North America became part of a counter-culture movement evident in the appearance of new dress styles, communes, mesmerism, and a revival of herbal remedies. Orson Fowler himself was known for his octogonal house. |

||

Throughout, however, phrenology was rejected by mainstream academia, and was for instance excluded from the [[British Association for the Advancement of Science]]. The popularity of phrenology fluctuated during the 19th century, with some researchers comparing the field to [[astrology]], [[chiromancy]], or merely a fairground attraction, while others wrote serious scientific articles on the subject. The last phrenology book in English to receive serious consideration by mainstream science was The Brain and Its Physiology (1846) by Daniel Noble, but his friend, William Carpenter, wrote a lengthy review article that initiated his realization that phrenology could not be considered a serious science, and his later books reflect his acceptance of British psycho-physiology. |

Throughout, however, phrenology was rejected by mainstream academia, and was for instance excluded from the [[British Association for the Advancement of Science]]. The popularity of phrenology fluctuated during the 19th century, with some researchers comparing the field to [[astrology]], [[chiromancy]], or merely a fairground attraction, while others wrote serious scientific articles on the subject. The last phrenology book in English to receive serious consideration by mainstream science was The Brain and Its Physiology (1846) by Daniel Noble, but his friend, William Carpenter, wrote a lengthy review article that initiated his realization that phrenology could not be considered a serious science, and his later books reflect his acceptance of British psycho-physiology. |

||

Revision as of 14:37, 21 September 2010

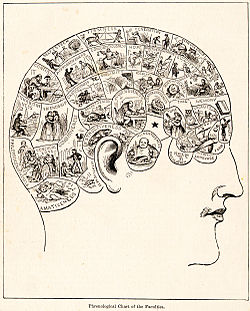

Phrenology (from Greek: φρήν, phrēn, "mind"; and λόγος, logos, "knowledge") was especially popular from about 1810 until 1840. Following the materialist notions of mental functions originating in the brain, phrenologists believed that human conduct could best be understood in neurological rather than abstract terms. It is now considered a pseudoscience. Developed by German physician Franz Joseph Gall in 1796,[1] the discipline was very popular in the 19th century. The principal British centre for phrenology was Edinburgh, where the Edinburgh Phrenological Society was established in 1820. In 1843, François Magendie referred to phrenology as "a pseudo-science of the present day."[2] Phrenological thinking was, however, influential in 19th-century psychiatry and modern neuroscience.[3]

Phrenology is based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions or modules (see modularity of mind).[4] Phrenologists believed that the mind has a set of different mental faculties, with each particular faculty represented in a different area of the brain. These areas were said to be proportional to a person's propensities, and the importance of the given mental faculty. It was believed that the cranial bone conformed in order to accommodate the different sizes of these particular areas of the brain in different individuals, so that a person's capacity for a given personality trait could be determined simply by measuring the area of the skull that overlies the corresponding area of the brain.

As a type of theory of personality, phrenology can be considered to be an advance over the old medical theory of the four humours. Phrenology, which focuses on personality and character, should be distinguished from craniometry, which is the study of skull size, weight and shape, and physiognomy, the study of facial features. However, researchers of these disciplines have claimed the ability to predict personality traits or intelligence (in fields such as anthropology/ethnology),[citation needed] and are alleged[by whom?] to have sometimes comprised a sort of scientific racism.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

The first attempts to measure skull shape scientifically, and its alleged relation to character, were performed by the German physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), who is considered the initiator of phrenology. Gall was one of the first researchers to consider the brain to be the source of all mental activity.

In 1809 Gall began writing his greatest[5] work "The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular, with Observations upon the possibility of ascertaining the several Intellectual and Moral Dispositions of Man and Animal, by the configuration of their Heads. It was not published until 1819. In the introduction to this main work, Gall makes the following statement in regard to his doctrinal principles, which comprise the intellectual basis of phrenology:

- That moral and intellectual faculties are innate

- That their exercise or manifestation depends on organization

- That the brain is the organ of all the propensities, sentiments and faculties

- That the brain is composed of as many particular organs as there are propensities, sentiments and faculties which differ essentially from each other.

- That the form of the head or cranium represents the form of the brain, and thus reflects the relative development of the brain organs.

Through careful observation and extensive experimentation, Gall believed he had established a relationship between aspects of character, called faculties, to precise organs in the brain. Gall's most important collaborator was Johann Spurzheim (1776-1832), who disseminated phrenology successfully in the United Kingdom and the United States. He popularized the term phrenology (from the Greek word "phrenos" meaning "brain": compare with the word "schizophrenia").[6]

Other significant phrenologists included the Scottish brothers George Combe (1788-1858) and Andrew Combe (1797-1847), who initiated the Phrenological Society of Edinburgh. This Edinburgh group included a number of extremely influential social reformers and intellectuals, including the publisher Robert Chambers, the astronomer John Pringle Nichol, the evolutionary environmentalist Hewett Cottrell Watson and asylum reformer William A.F. Browne. George Combe was the author of some of the most popular works on phrenology and mental hygiene, e.g., The Constitution of Man (1828) and Elements of Phrenology.

The American brothers Lorenzo Niles Fowler (1811-1896) and Orson Squire Fowler (1809-1887) were leading phrenologists of their time. Orson, together with associates Samuel Wells and Nelson Sizer, ran the phrenological business and publishing house Fowlers & Wells in New York City. Meanwhile, Lorenzo spent much of his life in England where he initiated the famous phrenological publishing house, L.N Fowler & Co., and gained considerable fame with his phrenology head (a china head showing the phrenological faculties), which has become a symbol of the discipline.

In the Victorian age, phrenology as a psychology was taken seriously and permeated the literature and novels of the day. Many prominent public figures such as the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher (a college classmate and initial partner of Orson Fowler) promoted phrenology actively as a source of psychological insight and self-knowledge. Thousands of people consulted phrenologists for advice in various matters, such as hiring personnel or finding suitable marriage partners. As such, phrenology as a brain science waned but developed into the popular psychology of the 19th century and functioned in approximately the same way as psychoanalysis permeated social thought and relationships a century later. Beginning during the 1840s, phrenology in North America became part of a counter-culture movement evident in the appearance of new dress styles, communes, mesmerism, and a revival of herbal remedies. Orson Fowler himself was known for his octogonal house.

Throughout, however, phrenology was rejected by mainstream academia, and was for instance excluded from the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The popularity of phrenology fluctuated during the 19th century, with some researchers comparing the field to astrology, chiromancy, or merely a fairground attraction, while others wrote serious scientific articles on the subject. The last phrenology book in English to receive serious consideration by mainstream science was The Brain and Its Physiology (1846) by Daniel Noble, but his friend, William Carpenter, wrote a lengthy review article that initiated his realization that phrenology could not be considered a serious science, and his later books reflect his acceptance of British psycho-physiology.

Phrenology was also very popular in the United States, where automatic devices for phrenological analysis were devised. One such Automatic Electric Phrenometer is displayed in the Collection of Questionable Medical Devices in the Science Museum of Minnesota in Saint Paul.

During the early 20th century, a revival of interest in phrenology occurred on the fringe, partly because of studies of evolution, criminology and anthropology (as pursued by Cesare Lombroso). The most famous British phrenologist of the 20th century was the London psychiatrist Bernard Hollander (1864-1934). His main works, The Mental Function of the Brain (1901) and Scientific Phrenology (1902) are an appraisal of Gall's teachings. Hollander introduced a quantitative approach to the phrenological diagnosis, defining a method for measuring the skull, and comparing the measurements with statistical averages.

In Belgium, Paul Bouts (1900-1999) began studying phrenology from a pedagogical background, using the phrenological analysis to define an individual pedagogy. Combining phrenology with typology and graphology, he coined a global approach known as psychognomy.

Bouts, a Roman Catholic priest, became the main promoter of renewed 20th-century interest in phrenology and psychognomy in Belgium. He was also active in Brazil and Canada, where he founded institutes for characterology. His works Psychognomie and Les Grandioses Destinées individuelle et humaine dans la lumière de la Caractérologie et de l'Evolution cérébro-cranienne are considered standard works in the field. In the latter work, which examines the subject of paleoanthropology, Bouts developed a teleological and orthogenetical view on a perfecting evolution, from the paleo-encephalical skull shapes of prehistoric man, which he considered still prevalent in criminals and savages, towards a higher form of mankind, thus perpetuating phrenology's problematic racializing of the human frame. Bouts died on March 7, 1999, after which his work has been continued by the Dutch foundation PPP (Per Pulchritudinem in Pulchritudine), operated by Anette Müller, one of Bouts' students.

During the 1930s, Belgian colonial authorities in Rwanda used phrenology to explain the so-called superiority of Tutsis over Hutus.[citation needed]

Empirical refutation induced most scientists to abandon phrenology as a science by the early 20th century. For example, various cases were observed of clearly aggressive persons displaying a well-developed "benevolent organ", findings that contradicted the logic of the discipline. With advances in the studies of psychology and psychiatry, many scientists became skeptical of the claim that human character can be determined by simple, external measures.

On Monday, October 1, 2007 the State of Michigan began to impose a tax on phrenology services.[7]

Method

Phrenology was a complex process that involved feeling the bumps in the skull to determine an individual's psychological attributes. Franz Joseph Gall first believed that the brain was made up of 27 individual 'organs' that created one's personality, with the first 19 of these 'organs' believed to exist in other animal species. Phrenologists would run their fingertips and palms over the skulls of their patients to feel for enlargements or indentations. The phrenologist would usually take measurements of the overall head size using a caliper. With this information, the phrenologist would assess the character and temperament of the patient and address each of the 27 "brain organs". This type of analysis was used to predict the kinds of relationships and behaviors to which the patient was prone. In its heyday during the 1820s-1840s, phrenology was often used to predict a child's future life, to assess prospective marriage partners and to provide background checks for job applicants.

Gall's list of the "brain organs" was lengthy and specific, as he believed that each bump or indentation in a patient's skull corresponded to his "brain map". An enlarged bump meant that the patient utilized that particular "organ" extensively. The 27 areas were varied in function, from sense of color, to the likelihood of religiosity, to the potential to commit murder. Each of the 27 "brain organs" was located in a specific area of the skull. As a phrenologist felt the skull, he could refer to a numbered diagram showing where each functional area was believed to be located.

The 27 "brain organs" were:

- The instinct of reproduction (located in the cerebellum).

- The love of one's offspring.

- Affection and friendship.

- The instinct of self-defense and courage; the tendency to get into fights.

- The carnivorous instinct; the tendency to murder.

- Guile; acuteness; cleverness.

- The feeling of property; the instinct of stocking up on food (in animals); covetousness; the tendency to steal.

- Pride; arrogance; haughtiness; love of authority; loftiness.

- Vanity; ambition; love of glory (a quality "beneficent for the individual and for society").

- Circumspection; forethought.

- The memory of things; the memory of facts; educability; perfectibility.

- The sense of places; of space proportions, of time.

- The memory of people; the sense of people.

- The memory of words.

- The sense of language; of speech.

- The sense of colours.

- The sense of sounds; the gift of music.

- The sense of connectedness between numbers.

- The sense of mechanics, of construction; the talent for architecture.

- Comparative sagacity.

- The sense of metaphysics.

- The sense of satire; the sense of witticism.

- The poetical talent.

- Kindness; benevolence; gentleness; compassion; sensitivity; moral sense.

- The faculty to imitate; the mimic.

- The organ of religion.

- The firmness of purpose; constancy; perseverance; obstinacy.

Phrenology as a pseudoscience

| Claims | Shape of the head determines character, personality traits and criminality. |

|---|---|

| Related scientific disciplines | Medicine, Psychology |

| Year proposed | 1800 |

| Original proponents | Franz Joseph Gall |

| Subsequent proponents | Per Pulchritudinem in Pulchritudine |

| (Overview of pseudoscientific concepts) | |

Phrenology has long been dismissed[by whom?] as a pseudoscience because of neurological advances. During the discipline's heyday, phrenologists including Gall committed many errors.[citation needed] In his book The Beginner's Guide to Scientific Method Stephen S. Carey explains that pseudoscience can be defined as "fallacious applications of the scientific method" by today's standards. Phrenologists made dubious inferences between bumps in people's skulls and their personalities, claiming that the bumps were the determinant of personality. Some of the more valid assumptions of phrenology (e.g., that mental processes can be localized in the brain) remain in modern neuroimaging techniques and modularity of mind theory. Through advancements in modern medicine and neuroscience, scientists have universally concluded that feeling conformations of the outer skull is not an accurate predictor of behavior.[citation needed]

Popular culture

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (December 2008) |

- In Chapter XX of Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Duke pulls several printed handbills out of his carpet-bag which were advertising past "performances" (scams and cons) he had been involved in: "One bill said "The celebrated Dr. Armand de Montalban of Paris," would "lecture on the Science of Phrenology" at such and such a place, on the blank day of blank, at ten cents admission, and "furnish charts of character at twenty-five cents apiece." The Duke said that was "him"." (97) (Dover Thrift Edition)

- In Bram Stoker's Dracula, several characters make phrenological observations in describing other characters.

- Charlotte Brontë, as well as her sister Anne Brontë, display the belief in phrenology in their works.

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's fictional detective Sherlock Holmes makes occasional references to phrenology; namely in The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle where he deduces the intelligence of a hat's owner by the size of his head and also regarding to his arch-nemesis Professor Moriarty, deeming that his highly domed forehead as a mark of his superior intellect. Most importantly, in The Hound of the Baskervilles, Dr Mortimer makes an examination of Holmes' skull, remarking on the dolcicophalic features and the supra-orbital fossa.

- Popular Indian-English writer Amitav Ghosh's first novel The Circle of Reason (1986) has one of the main characters, Balaram practice phrenology obsessively.

- The hip hop band The Roots have an album called Phrenology.

- Terry Pratchett, in his Discworld series of books, describes the practice of Retro-phrenology as the practice of altering someone's character by giving them bumps on the head. You can go into a shop in Ankh-Morpork and order an artistic temperament with a tendency to introspection. What you actually get is hit on the head with a series of small hammers, but it keeps the money in circulation and gives people something to do.

- The comedy-musical play Heid (pronounced 'Heed', a Scottish inflection of the word 'Head') by Forbes Masson alluded to the phrenology work of George Combe, citing the pseudoscience's influence on a young Charles Darwin as an inspiration for writers.

- The film Pi depicts the main character, Max, outlining a portion of his skull according to a phrenology chart and proceeding to drill into that section to destroy a part of his brain that contained important information of a mathematical sequence that he thought nobody should know.

- In the film Men at Work, the character of Charlie Sheen claims to be a phrenologist to his love interest, unwilling to confess his real profession (garbage collector). When she seems skeptical, he goes so far as to give her a phrenology reading, offering hit or miss insights, including her love for mangos.

- Several literary critics have noted the influence of phrenology[8] (and physiognomy) in Edgar Allan Poe's fiction.[9]

- In the novel The War of the End of the World from Latin American writer Mario Vargas Llosa, one of the main characters is Galileo Gall, who is phrenologist and had adopted his new name because of Galileo Galilei and Franz Joseph Gall, founder of the science of phrenology.

- In the novel Moby-Dick by Herman Melville many references are made to phrenology and the narrator identifies himself as an amateur phrenologist.

- In NBC's hit series 30 Rock Kenneth the page mentions that he doesn't trust his superior, Pete Hornberger, because he has a ridge on a section of his skull associated with deviousness.

- Dr. House has a white phrenology bust often seen in his office on House M.D.

- In The Simpsons episode "Mother Simpson" when Smithers mentions phrenology was dismissed as quackery 160 years ago Mr. Burns replies "Of course you'd say that...you have the brainpan of a stagecoach tilter!"

See also

References

- ^ Graham, Patrick. (2001) Phrenology [videorecording (DVD)] : revealing the mysteries of the mind . Richmond Hill, Ont. : American Home Treasures. ISBN 0-7792-5135-0

- ^ Magendie, F (1843) An Elementary Treatise on Human Physiology. 5th Ed. Tr. John Revere. New York: Harper, p 150. (note the hyphen).

- ^ Simpson, D. (2005) Phrenology and the neurosciences: contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim ANZ Journal of Surgery. Oxford. Vol.75.6; p.475

- ^ Fodor, Jerry A. (1983). Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-56025-9 p.14, 23, 131 See also, Modularity of mind

- ^ 1833 "The American Journal of the Medical Sciences" Southern Society for Clinical Investigation

- ^ Source of the term "Phrenology", by John van Wyhe, History & Philosophy of Science, Cambridge University

- ^ Mlive.com blog

- ^ Edward Hungerford. "Poe and Phrenology", American Literature 1(1930): 209-31.

- ^ Erik Grayson. "Weird Science, Weirder Unity: Phrenology and Physiognomy in Edgar Allan Poe" Mode 1 (2005): 56-77. Also online.

External links

- The History of Phrenology on the Web by John van Wyhe, PhD.

- Phrenology: an Overview includes The History of Phrenology by John van Wyhe, PhD.

- The Phrenology Pages, a Belgian site advocating phrenology.

- Phrenology Today! Russian portal, advocating phrenology. Articles on so-called modern phrenology.

- Examples of phrenological tools can be seen in The Museum of Questionable Medical Devices, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S..

- Joseph Vimont: Traité de phrénologie humaine et comparée. (Paris, 1832-1835). Selected pages scanned from the original work. Historical Anatomies on the Web. US National Library of Medicine.

- Jean-Claude Vimont: "Phrénologie à Rouen, les moulages du musée Flaubert d'histoire de la médecine"

- Phrenology: History of a Classic Pseudoscience - by Steven Novella MD

- Historical Deadwood Newspaper accounts of C. R. Broadbent well known speaker on Phrenology and Physiology visit Deadwood SD 1878

- The Skeptic's Dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll

- Who Named It? Franz Joseph Gall Biography of Franz Joseph Gall and his creation: Phrenology.

- Phrenology by George Burgess (1829-1905) George Burgess, Phrenologist in Bristol, England 1861-1901.

- History of the Phrenology Bust as developed by Spurzheim.

- George Combe's Elements of Phrenology.

- Psychophysiognomy Today! Polish portal, advocating psychophysiognomy. Articles on modern psychophysiognomy and the current use of psychophysiognomy in the personal consultation CVonVideo

- Phrenology Tools of the Trade.

- Early accounts of Phrenology practice.