Disciple (Christianity): Difference between revisions

It is the cornerstone of Christian faith that Jesus Christ was resurrected from the dead, and this, along with His ministry and miracles IS the message the disciples proclaimed to the world. |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

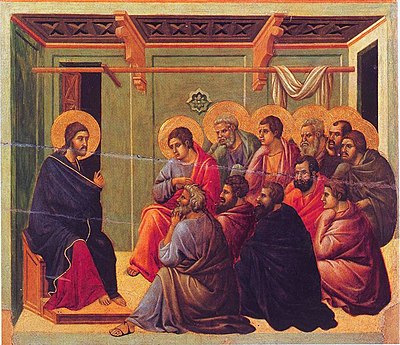

In [[Christianity]], the term '''disciple''' refers to a follower of [[Jesus]] and is found in the New Testament only in the Gospels and Acts. While Jesus had many disciples, he chose twelve to represent the tribes of Israel: |

In [[Christianity]], the term '''disciple''' refers to a follower of [[Jesus]] and is found in the New Testament only in the Gospels and Acts. While Jesus had many disciples, he chose twelve to represent the tribes of Israel: |

||

Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew (Nathanael), Matthew (Levi), Thomas (Didymus), James (son of Alphaeus), Jude, |

Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew (Nathanael), Matthew (Levi), Thomas (Didymus), James (son of Alphaeus), Jude, |

||

Simon (the Zealot) and, Judas Iscariot (who betrayed Jesus). Jesus was their Rabbi, and after his death they would proclaim his message (See [[Christian Oral Tradition]]) to the world. |

Simon (the Zealot) and, Judas Iscariot (who betrayed Jesus). Jesus was their Rabbi, and after his death and resurrection they would proclaim his message (See [[Christian Oral Tradition]]) to the world. |

||

== Etymology == |

== Etymology == |

||

Revision as of 15:05, 6 October 2012

In Christianity, the term disciple refers to a follower of Jesus and is found in the New Testament only in the Gospels and Acts. While Jesus had many disciples, he chose twelve to represent the tribes of Israel: Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew (Nathanael), Matthew (Levi), Thomas (Didymus), James (son of Alphaeus), Jude, Simon (the Zealot) and, Judas Iscariot (who betrayed Jesus). Jesus was their Rabbi, and after his death and resurrection they would proclaim his message (See Christian Oral Tradition) to the world.

Etymology

The term disciple is derived from the New Testament Greek word "μαθητής". (mathetes), which means a pupil (of a teacher) or an apprentice (to a master craftsman), coming to English by way of the Latin discipulus meaning "a learner". A disciple is different from an apostle, which instead means a "messenger, he that is sent". [1] While a disciple is one who learns from a teacher, in other words a student, an apostle is one sent to deliver those teachings or a message such as the Great Commission to others.

Great crowd and the seventy

In addition to the Twelve there is a much larger group of people, identified as disciples in the opening of the passage of the Sermon on the Plain 6:17. Furthermore, seventy (or seventy-two, depending on the source used) people are sent out in pairs to prepare the way for Jesus (Luke 10). They are sometimes referred to as the "Seventy" or the "Seventy Disciples". They are to eat any food offered, heal the sick and spread the word that God's reign is coming, that whoever hears them hears Jesus, whoever rejects them rejects Jesus, and whoever rejects Jesus rejects the One who sent him. In addition, they are granted great powers over the enemy and their names are written in heaven.

Undesirables

Jesus practiced open table fellowship, scandalizing his critics by dining with sinners, tax collectors, and women.

Sinners and tax collectors

The gospels use the term "sinners and tax collectors" to depict those he fraternized with. Sinners were Jews who violated purity rules, or generally any of the 613 mitzvot, or possibly Gentiles who violated Noahide Law, though halacha was still in dispute in the 1st century, see also Hillel and Shammai and Circumcision controversy in early Christianity. Tax collectors profited from the Roman economic system that the Romans imposed in Iudaea province, which was displacing Galileans in their own homeland, foreclosing on family land and selling it to absentee landlords. In the honor-based culture of the time, such behavior went against the social grain.

Samaritans

Samaritans, positioned between Jesus' Galilee and Jerusalem's Judea, were mutually hostile with Jews. In Luke and John, Jesus extends his ministry to Samaritans.

Females that followed Jesus

In Luke (10:38–42), Mary, sister of Lazarus is contrasted with her sister Martha, who was "cumbered about many things" while Jesus was their guest, while Mary had chosen "the better part," that of listening to the master's discourse. John names her as the "one who had anointed the Lord with perfumed oil and dried his feet with her hair" (11:2). In Luke, an unidentified "sinner" in the house of a Pharisee anoints Jesus' feet. Any pre-existing relationship between Jesus and Lazarus himself, prior to the miracle, is unspecified by John. In Catholic folklore, Mary, the sister of Lazarus, is seen as the same as Mary Magdalene.

Luke refers to a number of people accompanying Jesus and the twelve. From among them he names three women: "Mary, called Magdalene, ... and Joanna the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, and Susanna, and many others, who provided for them out of their resources" (Luke 8:2-3). Mary Magdalene and Joanna are among the women who went to prepare Jesus' body in Luke's account of the resurrection, and who later told the apostles and other disciples about the empty tomb and words of the "two men in dazzling clothes". Mary Magdalene is the most well-known of the disciples outside of the Twelve. More is written in the gospels about her than the other female followers. There is also a large body of lore and literature covering her.

Other gospel writers differ as to which women witness the crucifixion and witness to the resurrection. Mark includes Mary, the mother of James and Salome (not to be confused with Salomé the daughter of Herodias) at the crucifixion and Salome at the tomb. John includes Mary the wife of Clopas at the crucifixion.

Cleopas and companion on the road to Emmaus

In Luke, Cleopas is one of the two disciples to whom the risen Lord appears at Emmaus (Luke 24:18). Cleopas, with an unnamed disciple of Jesus' are walking from Jerusalem to Emmaus on the day of Jesus' resurrection. Cleopas and his friend were discussing the events of the past few days when a stranger asked them what they spoke of. The stranger is asked to join Cleopas and his friend for the evening meal. There the stranger is revealed, in blessing and breaking the bread, as the resurrected Jesus before he disappears. Cleopas and his friend hastened to Jerusalem to carry the news to the other disciples, to discover that Jesus had appeared there also and would do so again. The incident is without parallel in Matthew, Mark, or John.

Discipleship

"Love one another"

A definition of disciple is suggested by Jesus' self-referential example from the Gospel of John 13:34-35: "I give you a new commandment, that you love one another. Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another." (NRSV) Further definition by Jesus can be found in the Gospel of Luke, Chapter 14. Beginning with a testing trap laid out by his adversaries regarding observance of the Jewish Sabbath, Jesus uses the opportunity to lay out the problems with the religiosity of his adversaries against his own teaching by giving a litany of shocking comparisons between various, apparent socio-political and socio-economic realities versus the meaning of being his disciple.

"Be transformed"

Generally in Christian theology, discipleship is a term used to refer to a disciple's transformation from some other World view and practice of life into that of Jesus Christ, and so, by way of Trinitarian theology, of God himself.[2] [citation needed] Note the Apostle Paul's description of this process, that the disciple "not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect." (Romans 12:2) Therefore a disciple is not simply an accumulator of information or one who merely changes moral behavior in regard to the teachings of Jesus Christ, but seeks a fundamental shift toward the ethics of Jesus Christ in every way, including complete devotion to God.[citation needed] In several Christian traditions, the process of becoming a disciple is called the Imitation of Christ, and the ideal goes back to the Pauline Epistles.[3] The influential book the The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis further promoted this concept in the 14th century.

The Great Commission

Ubiquitous throughout Christianity is the practice of proselytization, making new disciples. In Matthew, at the beginning of Jesus' ministry, when calling his earliest disciples Simon (Peter) and Andrew, he says to them, "Follow me and I will make you fishers of men" (Matthew 4:19). Then, at the very end of his ministry Jesus institutes the Great Commission, commanding all present to "go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you" (Matthew 28:19-20a). Jesus has incorporated this practice into the very definition of being a disciple and experiencing discipleship.

Discipleship for The Twelve Disciples

The same process of transformation is also evident in the recorded experiences of the original twelve disciples of Jesus. Though regarded highly throughout Church history, the biblical texts themselves do not attempt to show the Twelve as faultless or even having a solid grasp of Jesus' own ministry, including a recognition of their part in it. All four gospel texts are not reluctant to convey the confusion and foibles of the Twelve in their attempt to internalize and live out the ministry of Jesus within their own discipleship.

Some other examples where the Twelve worked directly against the very center of the ministry of Jesus: In Matthew 19 Jesus rebuked the Twelve for their disinterest in children and Jesus explains that children are a model for a heavenly demeanor. In John 14, Philip demands that Jesus show them the Father, to which Jesus exasperatedly explains that they should know by then that if they have seen him, they have, in fact, seen the Father. In Matthew 18 the disciples argue over which of themselves will be the greatest when Jesus' kingdom comes into full effect. Jesus responds, to explain their gross misunderstanding of the humble and self-sacrificial nature of his teaching, "whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave.".

On the other hand, according to the Book of Acts, at Pentecost with the coming of the Holy Spirit, the disciples take on a new boldness, accuracy and discipline in their discipleship. It is from this point where we see the often confused band of disciples (not limited to the Twelve) mature into what is known as the Church (ekklesia εκκλησια), the forefathers and foremothers of the faith of all modern Christians worldwide.

Family and wealth

Jesus called on disciples to give up their wealth and their familial ties. In his society, family was the individual's source of identity, so renouncing it would mean becoming virtually nobody. In Luke {Luke 9:58-62}, Jesus uses a hyperbolic metaphor to stress the importance of this.

Other Biblical uses

Since the word disciple is used in English generally to mean "follower" or "pupil", it is applied to other Biblical characters, such as John the Baptist (c.f. John 1:35) and Isaiah (c.f. Isaiah 8:16).

Discipleship Movement

The "Discipleship Movement" (also known as the "Shepherding Movement") was an influential and controversial movement within some British and American churches, emerging in the 1970s and early 1980s.[citation needed] The doctrine of the movement emphasized the "one another" passages of the New Testament, and the mentoring relationship prescribed by the Apostle Paul in 2 Timothy 2:2 of the Holy Bible. It was controversial in that it gained a reputation for controlling and abusive behavior, with a great deal of emphasis placed upon the importance of obedience to one's own shepherd.[citation needed] The movement was later denounced by several of its founders, although some form of the movement continues today.[4][5][6]

Radical discipleship

Radical discipleship is a movement in practical theology that has emerged out of a yearning to follow the true message of Jesus and a discontentment with mainstream Christianity.[7] Radical Christians, such as Ched Myers and Lee Camp, believe mainstream Christianity has moved away from its origins, namely the core teachings and practices of Jesus such as turning the other cheek and rejecting materialism.[8][9] Radical is derived from the Latin word radix meaning "root", referring to the need for perpetual re-orientation towards the root truths of Christian discipleship.

See also

- Baptism

- Disciples of Jesus in Islam

- Divine filiation

- Great Commission, which includes the clause "and make disciples of all nations"

- Jesuism

- Radical discipleship

- Christian ethics

References

- ^ "Christian History: The Twelve Apostles". Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Romans 12:2

- ^ The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology by Alan Richardson, John Bowden 1983 ISBN 978-0-664-22748-7 pages 285-286

- ^ "Bible teacher Derek Prince dies at 88: Charismatic-renewal leader, author of 45 books lived in Jerusalem". WorldNetDaily. January 13, 2009.

- ^ Lawrence A. Pile (1990). "The Other Side of Discipleship". Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ^ "Charismatic Leaders Concede They Went Too Far: `Shepherding' was often accused by outsiders and former members of being cultlike in requiring members to obey leaders in all aspects of their personal lives". Los Angeles Times. March 24, 1990.

- ^ Dancer, Anthony (2005). William Stringfellow in Anglo-American Perspective. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 16–18.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Myers, Ched (1988). Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark's Story of Jesus. Orbis Books.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Camp, Lee C. (2003). Mere Discipleship: Radical Christianity in a Rebellious World. Brazos Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)