Disaster: Difference between revisions

| [accepted revision] | [pending revision] |

added examples of disaster |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

* [[Disaster recovery and business continuity auditing]] |

* [[Disaster recovery and business continuity auditing]] |

||

* [[Disaster opportunism]] |

* [[Disaster opportunism]] |

||

* [[Wikipedia:VisualEditor]] |

|||

* [[Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000]] |

* [[Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000]] |

||

* [[Hazard]] |

* [[Hazard]] |

||

| Line 49: | Line 50: | ||

* [[List of disasters]] |

* [[List of disasters]] |

||

* [[List of disasters by cost]] |

* [[List of disasters by cost]] |

||

* [[Wikipedia:Media Viewer]] |

|||

* [[Maritime disasters]] |

* [[Maritime disasters]] |

||

* [[Risk governance]] |

* [[Risk governance]] |

||

Revision as of 09:44, 17 June 2014

A disaster is a natural or man-made (or technological) hazard resulting in an event of substantial extent causing significant physical damage or destruction, loss of life, or drastic change to the environment. A disaster can be ostensively defined as any tragic event stemming from events such as earthquakes, floods, catastrophic accidents, fires, or explosions. It is a phenomenon that can cause damage to life and property and destroy the economic, social and cultural life of people.

In contemporary academia, disasters are seen as the consequence of inappropriately managed risk. These risks are the product of a combination of both hazard/s and vulnerability. Hazards that strike in areas with low vulnerability will never become disasters, as is the case in uninhabited regions.[1]

Developing countries suffer the greatest costs when a disaster hits – more than 95 percent of all deaths caused by disasters occur in developing countries, and losses due to natural disasters are 20 times greater (as a percentage of GDP) in developing countries than in industrialized countries.[2][3]

Etymology

The word disaster is derived from Middle French désastre and that from Old Italian disastro, which in turn comes from the Greek pejorative prefix δυσ-, (dus-) "bad"[4] and ἀστήρ (aster), "star".[5] The root of the word disaster ("bad star" in Greek) comes from an astrological sense of a calamity blamed on the sight of comets and asteroids.[6]

Classifications

Researchers have been studying disasters for more than a century, and for more than forty years disaster research. The studies reflect a common opinion when they argue that all disasters can be seen as being human-made, their reasoning being that human actions before the strike of the hazard can prevent it developing into a disaster. All disasters are hence the result of human failure to introduce appropriate disaster management measures.[7] Hazards are routinely divided into natural or human-made, although complex disasters, where there is no single root cause, are more common in developing countries. A specific disaster may spawn a secondary disaster that increases the impact. A classic example is an earthquake that causes a tsunami, resulting in coastal flooding.

Natural disaster

A natural disaster is a consequence when a natural hazard affects humans and/or the built environment. Human vulnerability, and lack of appropriate emergency management, leads to financial, environmental, or human impact. The resulting loss depends on the capacity of the population to support or resist the disaster: their resilience. This understanding is concentrated in the formulation: "disasters occur when hazards meet vulnerability". A natural hazard will hence never result in a natural disaster in areas without vulnerability.

Various phenomena like earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions, floods, tornadoes, blizzards,tsunamis, and cyclones are all natural hazards that kill thousands of people and destroy billions of dollars of habitat and property each year. However, natural hazards can strike in non-populated areas and never develop into disasters. However, the rapid growth of the world's population and its increased concentration often in hazardous environments has escalated both the frequency and severity of natural disasters. With the tropical climate and unstable land forms, coupled with deforestation, unplanned growth proliferation, non-engineered constructions which make the disaster-prone areas more vulnerable, tardy communication, poor or no budgetary allocation for disaster prevention, developing countries suffer more or less chronically by natural disasters. Asia tops the list of casualties due to natural disasters.

Man-made disasters

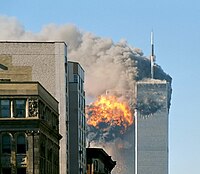

Man-made disasters are the consequence of technological or human hazards. Examples include stampedes, fires, transport accidents, industrial accidents, oil spills and nuclear explosions/radiation. War and deliberate attacks may also be put in this category. As with natural hazards, man-made hazards are events that have not happened, for instance terrorism. Man-made disasters are examples of specific cases where man-made hazards have become reality in an event.

See also

- Act of God

- Civil protection

- Crisis

- Disaster medicine

- Disaster convergence

- Disaster response

- Disaster recovery

- Disaster area

- Disaster research

- Disaster recovery plan

- Disaster recovery and business continuity auditing

- Disaster opportunism

- Wikipedia:VisualEditor

- Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000

- Hazard

- Emergency

- Emergency management

- Environmental emergency

- Human extinction

- List of disasters

- List of disasters by cost

- Wikipedia:Media Viewer

- Maritime disasters

- Risk governance

- Risk

- Risks to civilization, humans and planet Earth

- Sociology of disaster

- Survivalism

- The Klaxon.com

- Disaster film

- List of military disasters

- List of railway disasters

References

- ^ Quarantelli E.L. (1998). Where We Have Been and Where We Might Go. In: Quarantelli E.L. (ed). What Is A Disaster? London: Routledge. pp146-159

- ^ "World Bank:Disaster Risk Management".

- ^ Luis Flores Ballesteros. "Who’s getting the worst of natural disasters?" 54 Pesos May. 2010:54 Pesos 04 Oct 2008. <http://54pesos.org/2008/10/04/who%e2%80%99s-getting-the-worst-of-natural-disasters/>

- ^ "Dus, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus".

- ^ "Aster, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus".

- ^ http://etymonline.com/?term=disaster

- ^ B. Wisner, P. Blaikie, T. Cannon, and I. Davis (2004). At Risk – Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. Wiltshire: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-25216-4

Further reading

- Barton A.H. (1969). Communities in Disaster. A Sociological Analysis of Collective Stress Situations. SI: Ward Lock

- Catastrophe and Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster. Susanna M. Hoffman and Anthony Oliver-Smith, Eds.. Santa Fe NM: School of American Research Press, 2002

- G. Bankoff, G. Frerks, D. Hilhorst (eds.) (2003). Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development and People. ISBN 1-85383-964-7.

- D. Alexander (2002). Principles of Emergency planning and Management. Harpended: Terra publishing. ISBN 1-903544-10-6.

- Quarantelli, E. L. (2008). “Conventional Beliefs and Counterintuitive Realities”. Conventional Beliefs and Counterintuitive Realities in Social Research: an international Quarterly of the social Sciences, Vol. 75 (3): 873–904.

- Paul, B. K et al. (2003). “Public Response to Tornado Warnings: a comparative Study of the May 04, 2003 Tornadoes in Kansas, Missouri and Tennessee”. Quick Response Research Report, no 165, Natural Hazard Center, Universidad of Colorado

- Kahneman, D. y Tversky, A. (1984). “Choices, Values and frames”. American Psychologist 39 (4): 341–350.

- Beck, U. (2006). Risk Society, towards a new modernity. Buenos Aires, Paidos

- Aguirre, B. E & Quarantelli, E. H. (2008). “Phenomenology of Death Counts in Disasters: the invisible dead in the 9/11 WTC attack”. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters. Vol. 26 (1): 19–39.

- Wilson, H. (2010). “Divine Sovereignty and The Global Climate Change debate”. Essays in Philosophy. Vol. 11 (1): 1–7

- Uscher-Pines, L. (2009). “Health effects of Relocation following disasters: a systematic review of literature”. Disasters. Vol. 33 (1): 1–22.

- Hirshleifer, Jack (2008). "Disaster and Recovery". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Scheper-Hughes, N. (2005). “Katrina: the disaster and its doubles”. Anthropology Today. Vol. 21 (6).

- Phillips, B. D. (2005). “Disaster as a Discipline: The Status of Emergency Management Education in the US”. International Journal of Mass-Emergencies and Disasters. Vol. 23 (1): 111–140.

- Mileti, D. and Fitzpatrick, C. (1992). “The causal sequence of Risk communication in the Parkfield Earthquake Prediction experiment”. Risk Analysis. Vol. 12: 393–400.

- Korstanje, M. (2011). "The Scientific Sensationalism: short commentaries along with scientific risk perception". E Journalist. Volume 10, Issue 2.

- Korstanje, M. (2011). "Swine Flu, beyond the principle of Reisilience". International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, Vol. 2 Iss: 1, pp. 59–73

External links

- The Disaster Roundtable Information on past and future Disaster Roundtable workshops

- EM-DAT The EM-DAT International Disaster Database

- RSOE EDIS Emergency and Disaster Information Service An up-to-the-minute world wide map showing current disasters.

- Articles On Food Shortage – Food Shortage Information.

- Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System A United Nations and European Commission sponsored website for disaster information.

- United Nations Programme for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response United Nations programme covering the full disaster management cycle with usage of space technology

- Top 100 aviation disasters on AirDisaster.com

- Disaster Video Archive Archive Footage of Major Disasters

- Guinness Book of World Records

- The world's worst massacres Whole Earth Review

- War Disaster and Genocide

- Geohotspots

- Disaster Video Disaster News and Video

- Disaster Alert Notification and Reporting

- RSOE EDIS (Emergency Disaster and Information Service): world map showing current disasters

- The Disaster News Network – Live Monitors and Updates about Disasters

- The Calamity of Disaster – Recognizing the possibilities, planning for the event, managing crisis and coping with the effects.

- Corporate Disaster Resource Network, India – Needs and Offers matched online.