Hamhung: Difference between revisions

→History: added ref |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 8 sources. #IABot |

||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

In 1995, Hamhŭng witnessed, thus far, one of the only documented challenges to the North Korean [[Government of North Korea|government]] when [[North Korean famine|famine]]-ravaged [[Korean People's Army|soldiers]] began a march toward [[Pyongyang]]. The revolt was quelled and the unit of soldiers was disbanded.<ref>{{cite book |last=Becker |first=Jasper |authorlink= |title=Rogue Regime : Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea |date=May 2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=USA |language=English|pages=199-200 |isbn=9780198038108}}</ref> |

In 1995, Hamhŭng witnessed, thus far, one of the only documented challenges to the North Korean [[Government of North Korea|government]] when [[North Korean famine|famine]]-ravaged [[Korean People's Army|soldiers]] began a march toward [[Pyongyang]]. The revolt was quelled and the unit of soldiers was disbanded.<ref>{{cite book |last=Becker |first=Jasper |authorlink= |title=Rogue Regime : Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea |date=May 2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=USA |language=English|pages=199-200 |isbn=9780198038108}}</ref> |

||

The North Korean famine of the 1990s appears to have had a disproportionate effect on the people of Hamhung. Andrew Natsios, a former aid worker, USAID Administrator, and author of ''The Great North Korean Famine'', described Hamhung as "the city most devastated by [the] famine."<ref>{{cite web |

The North Korean famine of the 1990s appears to have had a disproportionate effect on the people of Hamhung. Andrew Natsios, a former aid worker, USAID Administrator, and author of ''The Great North Korean Famine'', described Hamhung as "the city most devastated by [the] famine."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usip.org/pubs/specialreports/sr990802.html |title=The Politics of Famine in North Korea |accessdate=2009-01-31 |work=U.S. Institute of Peace |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20090122071411/http://www.usip.org:80/pubs/specialreports/sr990802.html |archivedate=January 22, 2009 }}</ref> Contemporary published reports from ''[[The Washington Post]]''<ref>{{cite news |title=Beyond a Wall of Secrecy, Devastation|work=Washington Post|date=1997-10-19|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/18/AR2006101800728_pf.html | first=Keith B. | last=Richburg | accessdate=2010-05-04}}</ref> and [[Reuters]]<ref>{{cite news |title=North Korea: Whole Generation of Children Affected by North Korean Famine.|work=Reuters|date=1999-05-19|url=http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist/RTV/1999/05/19/905190018/}}</ref> describe the presence of numerous fresh graves on the surrounding hillsides, and report that many of Hamhung's children were stunted by malnutrition. One survivor claimed that more than 10% of the city's population died, with another 10% fleeing the city in search of food.<ref>http://hamhung.co.tv/</ref> Despite previously being closed to foreigners, foreign nationals can now travel to Hamhung through the few approved North Korean tour operators."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.youngpioneertours.com/|title=Recent news.|accessdate=2010-06-25|work=U.S. Institute of Peace}}</ref> |

||

There is speculation that Hamhung, with its high proportion of chemists and the site of a chemical-industrial complex built by the Japanese during World War II, is the center for North Korea's methamphetamine production.<ref>{{Cite news |title=North Korea's Addicting Export: Crystal Meth |author= |first=Isaac |last=Stone Fish |url=http://pulitzercenter.org/projects/china-meth-north-korea-addicting-export|newspaper=Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting |date=20 June 2011 |accessdate=2011-06-27}}</ref> |

There is speculation that Hamhung, with its high proportion of chemists and the site of a chemical-industrial complex built by the Japanese during World War II, is the center for North Korea's methamphetamine production.<ref>{{Cite news |title=North Korea's Addicting Export: Crystal Meth |author= |first=Isaac |last=Stone Fish |url=http://pulitzercenter.org/projects/china-meth-north-korea-addicting-export|newspaper=Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting |date=20 June 2011 |accessdate=2011-06-27}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:51, 8 January 2016

Hamhung

함흥시 | |

|---|---|

| Korean transcription(s) | |

| • Chosŏn'gŭl | 함흥시 |

| • Hancha | 咸興市 |

| • McCune-Reischauer | Hamhŭng-si |

| • Revised Romanization | Hamheung-si |

A view of Hamhung | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kwannam |

| Area | |

| • Total | 330 km2 (130 sq mi) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • Total | 768,551 |

| • Dialect | Hamgyŏng |

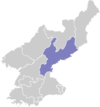

Hamhŭng (Hamhŭng-si; Korean pronunciation: [hamhɯŋ ɕʰi]) is North Korea's second largest city, and the capital of South Hamgyŏng Province. In late 2005, nearby Hŭngnam was made a ward (kuyŏk) within Hamhŭng-si.[1] It has a population of 768,551 as of 2008.[2]

Administrative Divisions

Hamhŭng is divided into 7 kuyŏk (wards):

|

Geography

Hamhŭng is on the left branch of the Sŏngch'ŏn River, on the eastern part of the Hamhŭng plain (함흥평야), in South Hamgyŏng Province, northeast North Korea. The Tonghŭngsan is 319 m high.

History

Yi Sung-ke, founder of the Yi Dynasty, retired to the city after a successful palace coup by his son Yi Bang-won in 1400. Though his son sent envoys to reconcile, his father had them all killed. A modern Korean expression, King's envoy to Hamheung ([Hamheungchasa] Error: {{Lang}}: Latn text/non-Latn script subtag mismatch (help)), refers to a person who goes off on a journey but is never heard from again.[3] It was known as Kankō during Japanese rule of Korea between 1910 and 1945. It was liberated by the Red Army on 22 August 1945.

The city was heavily destroyed (80–90%) during the Korean War and was occupied by ROK troops between 17 October 1950 and 17 December 1950. From 1955–1962, Hamhŭng was the object of a large-scale program of reconstruction and development by East Germany including the build-up of various construction-related industries and intense training measures for Korean construction workers, engineers, city planners and architects. The project ended two years earlier than scheduled and with a low profile because of the Sino-Soviet conflict and the opposing positions that North Korea and East Germany took on that issue.[4]

From 1960 to 1967, Hamhŭng was administered separately from South Hamgyŏng as a Directly Governed City (Chikhalsi), but before 1960, and since 1967, the city has been part of South Hamgyŏng Province.

In 1995, Hamhŭng witnessed, thus far, one of the only documented challenges to the North Korean government when famine-ravaged soldiers began a march toward Pyongyang. The revolt was quelled and the unit of soldiers was disbanded.[5]

The North Korean famine of the 1990s appears to have had a disproportionate effect on the people of Hamhung. Andrew Natsios, a former aid worker, USAID Administrator, and author of The Great North Korean Famine, described Hamhung as "the city most devastated by [the] famine."[6] Contemporary published reports from The Washington Post[7] and Reuters[8] describe the presence of numerous fresh graves on the surrounding hillsides, and report that many of Hamhung's children were stunted by malnutrition. One survivor claimed that more than 10% of the city's population died, with another 10% fleeing the city in search of food.[9] Despite previously being closed to foreigners, foreign nationals can now travel to Hamhung through the few approved North Korean tour operators."[10]

There is speculation that Hamhung, with its high proportion of chemists and the site of a chemical-industrial complex built by the Japanese during World War II, is the center for North Korea's methamphetamine production.[11]

Economy

Hamhŭng is an important chemical industry center in the DPRK. It is an industrial city which serves as a major port for North Korean foreign trade. Production includes textiles (particularly vinalon), metalware, machinery, refined oil and processed food.

Prison camps

Two large reeducation camps are located near Hamhung: Kyo-hwa-so No. 9 is in northeastern Hamhung, Kyo-hwa-so No. 22 is in Yonggwang County north of Hamhung.[12]

Transportation

The city is a transportation hub, connecting various eastern ports and the northern interior area. Hamhung Station is on the Pyongra Line railway. This city is connected by air too, with Toksan Airport.

Culture

It has a national museum and a branch academy of science.

Hamhŭng is home to the Hamhŭng University of Education, Hamhŭng University of Pharmacy, Hamhŭng University of Chemistry and Hamhŭng University of Medicine. Professional colleges in Hamhǔng include the Hamhǔng College of Quality Control, the Hamhŭng Hydrographic and Power College, and the Hamhǔng College of Electronics and Automation.

Hamhŭng also hosts the Hamhŭng Grand Theatre the largest theatre in North Korea.[13]

Food

Hamhŭng is famous for its naengmyŏn.

People born in Hamhŭng

- Yi Seonggye (이성계; 1335–1408), the founder of the Chosŏn dynasty, Korea's last royal line

- Ahn Soo-kil (안수길; 1911–1977), writer

- Richard E. Kim (1932–2009), writer

- Yoon Kwang-cho (윤광조; born 1946), ceramic artist

- Yang Hyong-sop (born 1925), President of the Supreme People's Assembly from 1984–1998

See also

Sister cities

Shanghai, People's Republic of China - since 1982

Shanghai, People's Republic of China - since 1982

Footnotes

- ^ 행정구역 개편 일지. NKChosun (in Korean). Retrieved 2006-04-29.

- ^ United Nations Statistics Division; 2008 Census of Population of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea conducted on 1–15 October 2008 (pdf-file) Retrieved on 2009-03-18.

- ^ "Characters". How Koreans Talk. UnhengNamu. 2002. pp. 094–095. ISBN 89-87976-95-5.

- ^ For more information on the post-War reconstruction project, see Frank, Rüdiger (December 1996). Die DDR und Nordkorea. Der Wiederaufbau der Stadt Hamhŭng von 1954–1962 (in German). Aachen: Shaker. ISBN 3-8265-5472-8.

- ^ Becker, Jasper (May 2005). Rogue Regime : Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 9780198038108.

- ^ "The Politics of Famine in North Korea". U.S. Institute of Peace. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Richburg, Keith B. (1997-10-19). "Beyond a Wall of Secrecy, Devastation". Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ "North Korea: Whole Generation of Children Affected by North Korean Famine". Reuters. 1999-05-19.

- ^ http://hamhung.co.tv/

- ^ "Recent news". U.S. Institute of Peace. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- ^ Stone Fish, Isaac (20 June 2011). "North Korea's Addicting Export: Crystal Meth". Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ "The Hidden Gulag – Exposing Crimes against Humanity in North Korea's Vast Prison System (p. 93 - 100)" (PDF). The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Korea Travel Guide. Lonely Planet. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

Further reading

- Dormels, Rainer. North Korea's Cities: Industrial facilities, internal structures and typification. Jimoondang, 2014. ISBN 978-89-6297-167-5

External links

- North Korea Uncovered, (North Korea Google Earth) Maps out Hamhung's economic infrastructure, including railways, hotels, tourist destinations, cultural facilities, ports, and electricity grid on Google Earth.

- Hamhung, Haunted City, Compares newly revealed Google Earth imagery of Hamhung—imagery which reveals many of the hills around the city to be packed with graves—with published reports of severe famine in Hamhung during the 1990s.

- Young Pioneer Tours, Information on the opening up of Hamhung to tourists, and details on tours there.

- City profile of Hamhung