Brexit: Difference between revisions

Keep it simple; there's plenty of details following in the lead and article, but the lead sentence must be easy to read and unambiguous →top |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2016}}{{Brexit}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2016}}{{Brexit}} |

||

'''Brexit''' |

'''Brexit''' refers to the [[United Kingdom]]'s intended [[withdrawal from the European Union]] following an [[United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, 2016|advisory referendum held in June 2016]] in which 52% of votes were cast in favour of leaving the EU. The term Brexit is a [[portmanteau]] of the words ''Britain'' and ''exit''. |

||

Prime Minister [[Theresa May]] announced the government's intention to invoke [[Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union]], the formal procedure for withdrawing, by the end of March 2017, which, within the treaty terms, would put the UK on a course to leave the EU by the end of March 2019.<ref name=bbc-trigger>{{cite news|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-37532364|title=Brexit: PM to trigger Article 50 by end of March|date=2016-10-02|newspaper=BBC News|language=en-GB|access-date=2016-10-02}}</ref> May has promised a [[Bill (law)|bill]] to remove the [[European Communities Act 1972 (UK)|European Communities Act 1972]] from the [[statute book]] and to incorporate existing [[European Union law|EU laws]] into [[Law of the United Kingdom|UK domestic law]].<ref name=bbc-trigger /> The terms of withdrawal have not yet been negotiated within the EU; in the meantime, the UK remains a full member of the European Union. |

Prime Minister [[Theresa May]] announced the government's intention to invoke [[Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union]], the formal procedure for withdrawing, by the end of March 2017, which, within the treaty terms, would put the UK on a course to leave the EU by the end of March 2019.<ref name=bbc-trigger>{{cite news|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-37532364|title=Brexit: PM to trigger Article 50 by end of March|date=2016-10-02|newspaper=BBC News|language=en-GB|access-date=2016-10-02}}</ref> May has promised a [[Bill (law)|bill]] to remove the [[European Communities Act 1972 (UK)|European Communities Act 1972]] from the [[statute book]] and to incorporate existing [[European Union law|EU laws]] into [[Law of the United Kingdom|UK domestic law]].<ref name=bbc-trigger /> The terms of withdrawal have not yet been negotiated within the EU; in the meantime, the UK remains a full member of the European Union. |

||

Revision as of 08:23, 1 November 2016

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

Brexit refers to the United Kingdom's intended withdrawal from the European Union following an advisory referendum held in June 2016 in which 52% of votes were cast in favour of leaving the EU. The term Brexit is a portmanteau of the words Britain and exit.

Prime Minister Theresa May announced the government's intention to invoke Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, the formal procedure for withdrawing, by the end of March 2017, which, within the treaty terms, would put the UK on a course to leave the EU by the end of March 2019.[1] May has promised a bill to remove the European Communities Act 1972 from the statute book and to incorporate existing EU laws into UK domestic law.[1] The terms of withdrawal have not yet been negotiated within the EU; in the meantime, the UK remains a full member of the European Union.

The UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor of the EU, in 1973, and confirmed its membership in a 1975 referendum by 67% of the votes. Historical opinion polls 1973-2015 mostly revealed majorities in favour of remaining in the EEC or EU. In the 1970s and 1980s, withdrawal from the EEC was advocated mainly by some Labour Party and trade union figures. From the 1990s, withdrawal from the EU was advocated mainly by some Conservatives and by the newly founded UK Independence Party (UKIP).

The term "Brexit"

Brexit (and its early variant, Brixit),[2] is a portmanteau of "Britain" and "exit". It was derived by analogy from Grexit, referring to a hypothetical withdrawal of Greece from the eurozone (and possibly also the EU).[3] The term Brexit may have first been used in reference to a possible UK withdrawal from the EU by Peter Wilding in a Euractiv blog post on 15 May 2012.[4][5]

Historical background

Opinion polls taken after EU accession in 1973 until the end of 2015 mostly revealed popular British support for EEC or EU membership.[6] Similarly, in the United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum of 1975, two thirds of British voters favoured membership. A clear exception was the year 1980, the first year of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's term of office, when the highest ever rejection of membership was measured, with 65% opposed to and 26% in favour of membership.[7] After Thatcher had negotiated a rebate of British membership payments in 1984, those favouring the EEC maintained a lead in the opinion polls, except during 2000, as Prime Minister Tony Blair aimed for closer EU integration including adoption of the euro currency, and around 2011, as immigration into the United Kingdom became increasingly noticeable.[7] As late as December 2015 there was, according to ComRes, a clear majority in favour of remaining in the EU, albeit with a warning that voter intentions would be considerably influenced by the outcome of Prime Minister David Cameron's ongoing EU reform negotiations, especially with regards to the two issues of "safeguards for non-Eurozone member states" and "immigration".[8] The following events are relevant.

Founding of the EEC in 1957 and British applications for membership

The UK was not a signatory to the Treaty of Rome which created the EEC in 1957. The country subsequently applied to join the organisation in 1963 and again in 1967, but both applications were vetoed by the President of France, Charles de Gaulle, who said that "a number of aspects of Britain's economy, from working practices to agriculture" had "made Britain incompatible with Europe" and that Britain harboured a "deep-seated hostility" to any pan-European project.[9] Once de Gaulle had relinquished the French presidency, the UK made a third and successful application for membership. The Treaty of Accession was signed in January 1972 by the prime minister Edward Heath, leader of the Conservative party.[10] Parliament's European Communities Act 1972 was enacted on 17 October and the UK's instrument of ratification was deposited the next day (18 October),[11] letting the United Kingdom's membership of the EEC, or "Common Market", come into effect on 1 January 1973.[12] The opposition Labour Party, led by Harold Wilson, contested the October 1974 general election with a commitment to renegotiate Britain's terms of membership of the EEC and then hold a referendum on whether to remain in the EEC on the new terms.[13]

1975 referendum

In 1975, the United Kingdom held a referendum on whether the UK should remain in the EEC. All of the major political parties and mainstream press supported continuing membership of the EEC. However, there were significant splits within the ruling Labour party, the membership of which had voted 2:1 in favour of withdrawal at a one-day party conference on 26 April 1974. Since the cabinet was split between strongly pro-European and strongly anti-European ministers, Harold Wilson suspended the constitutional convention of Cabinet collective responsibility and allowed ministers to publicly campaign on either side. Seven of the twenty-three members of the cabinet opposed EEC membership.[14]

On 5 June 1975, the electorate were asked to vote yes or no on the question: "Do you think the UK should stay in the European Community (Common Market)?" Every administrative county in the UK had a majority of "Yes", except the Shetland Islands and the Outer Hebrides. With a turnout of 64%, the outcome of the vote was 67.2% in favour of staying in, and the United Kingdom remained a member of the EEC.[15]

Between referendums

In 1979 the United Kingdom opted out of the newly formed European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) which was the precursor to the creation of the euro.

The opposition Labour Party campaigned in the 1983 general election on a commitment to withdraw from the EEC without a referendum.[16] It was heavily defeated as the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher was re-elected. The Labour Party subsequently changed its policy.[16]

In 1985 the United Kingdom ratified the Single European Act, the first major revision to the Treaty of Rome without a referendum with the full support HM Government of Margaret Thatcher.

In October 1990 - despite the deep reservations of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher but under pressure from her senior ministers - the United Kingdom joined the ERM with the pound sterling pegged to the deutschmark. In November 1990 Thatcher resigned as Prime Minister amid internal divisions within the Conservative Party arising partly from her increasingly Eurosceptic views. In September 1992 the United Kingdom was forced to withdraw from the ERM after the pound sterling came under pressure from currency speculators (an episode known as Black Wednesday). The resulting cost to UK taxpayers was estimated to be in excess of £3 billion.[17][18]

As a result of the Maastricht Treaty, the EEC became the European Union on 1 November 1993.[19] The new name reflected the evolution of the organisation from an economic union into a political union.[20] As a result of the Lisbon Treaty, which entered into force on 1 December 2009, the Maastricht Treaty is now known, in updated form as, the Treaty on European Union (2007) or TEU, and the Treaty of Rome is now known, in updated form, as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2007) or TFEU.

The Referendum Party was formed in 1994 by Sir James Goldsmith to contest the 1997 general election on a platform of providing a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU.[21] It fielded candidates in 547 constituencies at that election and won 810,860 votes, 2.6% of total votes cast.[22] It failed to win a single parliamentary seat as its vote was spread out, losing its deposit (funded by Goldsmith) in 505 constituencies.[22]

The UK Independence Party (UKIP), a Eurosceptic political party, was also formed, in 1993. It achieved third place in the UK during the 2004 European elections, second place in the 2009 European elections and first place in the 2014 European elections, with 27.5% of the total vote. This was the first time since the 1910 general election that any party other than the Labour or Conservative parties had taken the largest share of the vote in a nationwide election.[23]

In 2014, UKIP won two by-elections, triggered when the sitting Conservative MPs defected to UKIP and then resigned. These were their first elected MPs. At the 2015 general election UKIP took 12.6% of the total vote and held one of the two seats won in 2014.[24]

2016 referendum

Negotiations for EU Reform

In 2012, Prime Minister David Cameron rejected calls for a referendum on the UK's EU membership, but suggested the possibility of a future referendum to gauge public support.[25][26] According to the BBC, "The prime minister acknowledged the need to ensure the UK's position within the European Union had 'the full-hearted support of the British people' but they needed to show 'tactical and strategic patience'."[27]

Under pressure from many of his MPs and from the rise of UKIP, in January 2013, Cameron announced that a Conservative government would hold an in–out referendum on EU membership before the end of 2017, on a renegotiated package, if elected in 2015.[28]

The Conservative Party unexpectedly won the 2015 general election with a majority. Soon afterwards the European Union Referendum Act 2015 was introduced into Parliament to enable the referendum. Cameron favoured remaining in a reformed European Union and sought to renegotiate on four key points: protection of the single market for non-eurozone countries, reduction of "red tape", exempting Britain from "ever-closer union", and restricting EU immigration.[29]

The outcome of the renegotiations was announced in February 2016. Some limits to in-work benefits for new EU immigrants were agreed, but before they could be applied, a country such as the UK would have to get permission from the European Commission and then from the European Council.[30]

In a speech to the House of Commons on 22 February 2016, Cameron announced a referendum date of 23 June 2016 and commented on the renegotiation settlement.[31] Cameron spoke of an intention to trigger the Article 50 process immediately following a leave vote and of the "two-year time period to negotiate the arrangements for exit."[32]

Campaign groups

The official campaign group for leaving the EU was Vote Leave.[33] Other major campaign groups included Leave.EU,[34] Grassroots Out, Get Britain Out and Better Off Out.[35]

The official campaign to stay in the EU, chaired by Stuart Rose, was known as Britain Stronger in Europe, or informally as Remain. Other campaigns supporting remaining in the EU included Conservatives In,[36] Labour in for Britain,[37] #INtogether (Liberal Democrats),[38] Greens for a Better Europe,[39] Scientists for EU,[40] Environmentalists For Europe,[41] Universities for Europe[42] and Another Europe is Possible.[43]

Referendum result

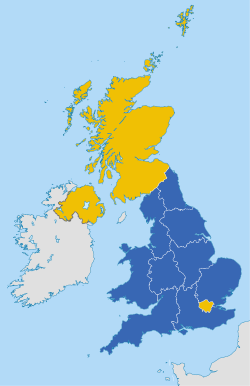

The result was announced on the morning of 24 June: 51.9% voted in favour of leaving the European Union and 48.1% voted in favour of remaining a member of the European Union.[44][45] Comprehensive results are available from the UK Electoral Commission Referendum Results site. A petition calling for a second referendum attracted more than four million signatures,[46][47] but was rejected by the government on 9 July.[48]

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Leave the European Union | 17,410,742 | 51.89 |

| Remain a member of the European Union | 16,141,241 | 48.11 |

| Valid votes | 33,551,983 | 99.92 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 25,359 | 0.08 |

| Total votes | 33,577,342 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 46,500,001 | 72.21 |

| Source: Electoral Commission[49] | ||

| National referendum results (excluding invalid votes) | |

|---|---|

| Leave 17,410,742 (51.9%) |

Remain 16,141,241 (48.1%) |

| ▲ 50% | |

| Region | Electorate | Voter turnout, of eligible |

Votes | Proportion of votes | Invalid votes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remain | Leave | Remain | Leave | ||||||

| East Midlands | 3,384,299 | 74.2% | 1,033,036 | 1,475,479 | 41.18% | 58.82% | 1,981 | ||

| East of England | 4,398,796 | 75.7% | 1,448,616 | 1,880,367 | 43.52% | 56.48% | 2,329 | ||

| Greater London | 5,424,768 | 69.7% | 2,263,519 | 1,513,232 | 59.93% | 40.07% | 4,453 | ||

| North East England | 1,934,341 | 69.3% | 562,595 | 778,103 | 41.96% | 58.04% | 689 | ||

| North West England | 5,241,568 | 70.0% | 1,699,020 | 1,966,925 | 46.35% | 53.65% | 2,682 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 1,260,955 | 62.7% | 440,707 | 349,442 | 55.78% | 44.22% | 374 | ||

| Scotland | 3,987,112 | 67.2% | 1,661,191 | 1,018,322 | 62.00% | 38.00% | 1,666 | ||

| South East England | 6,465,404 | 76.8% | 2,391,718 | 2,567,965 | 48.22% | 51.78% | 3,427 | ||

| South West England (inc Gibraltar) | 4,138,134 | 76.7% | 1,503,019 | 1,669,711 | 47.37% | 52.63% | 2,179 | ||

| Wales | 2,270,272 | 71.7% | 772,347 | 854,572 | 47.47% | 52.53% | 1,135 | ||

| West Midlands | 4,116,572 | 72.0% | 1,207,175 | 1,755,687 | 40.74% | 59.26% | 2,507 | ||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 3,877,780 | 70.7% | 1,158,298 | 1,580,937 | 42.29% | 57.71% | 1,937 | ||

Political effects

The political scene in the UK went through substantial change and shock after the referendum. After the result was declared, Cameron announced that he would resign by October.[50] In the event, he stood down on 13 July, with Theresa May becoming Prime Minister. George Osborne was replaced as Chancellor of the Exchequer by Philip Hammond, Boris Johnson was appointed Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and David Davis became Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn lost a vote of confidence among his parliamentary party and a leadership challenge was launched, while on 4 July, Nigel Farage announced his resignation as head of UKIP.[51]

Outside the UK many Eurosceptic leaders celebrated and expected others to follow the UK example. However, opinion polls a week after the Brexit vote showed strongly increased support for the EU in most of Europe. The right-wing Dutch populist Geert Wilders said that the Netherlands should follow Britain's example and hold a referendum on whether the Netherlands should stay in the European Union.[52] However, opinion polls in the fortnight following the British referendum show that the immediate reaction in the Netherlands and other European countries was a decline in support for Eurosceptic movements.[53]

A week after the referendum, Gordon Brown, a former Labour Party leader and the prime minister who had signed the Lisbon Treaty in 2007, warned of a danger that in the next decade the country would be refighting the referendum. He wrote that remainers were feeling they must be pessimists to prove that Brexit is unmanageable without catastrophe, while leavers optimistically claim economic risks are exaggerated.[54]

The previous leader of the Labour party and prime minister (1997-2007), Tony Blair, speaking for himself,[55] said in a BBC interview on 28 October 2016[56] that he believes public opinion may change once the implications of Brexit are fully understood. Blair, who had been one of the signatories to the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe in 2004 that had remained unratified by the UK and other states,[57] now called for a second referendum, a decision through parliament or a general election to decide finally if Britain should leave the EU,[58] and commented:

You can't just dismiss the 16m people [who voted remain] either and say their views are of no account. (...) they represent people who genuinely believe that in the 21st century for Britain to leave the biggest political union and the biggest commercial market right on our doorstep is a serious mistake.[59]

"Article 50" and the procedure for leaving the EU

Advisory status of the referendum

As was the case with the 1975 referendum, the 2016 referendum did not directly require the government to do anything in particular. It does not require the government to initiate, or even schedule, the Article 50 procedure.[60] The UK government stated that they would expect a leave vote to be followed by withdrawal, not by a second vote.[61] Although Cameron stated during the campaign that he would invoke Article 50 straight away in the event of a leave victory,[62] he refused to allow the Civil Service to make any contingency plans, something the Foreign Affairs Select Committee later described as "an act of gross negligence."[63] Following the referendum result Cameron announced before the Conservative Party conference that he would resign by October, and that it would be for the incoming Prime Minister to invoke Article 50.[64] Quoting the ex-Prime Minister's media release on the UK government's web portal, gov.uk:

A negotiation with the European Union will need to begin under a new Prime Minister, and I think it is right that this new Prime Minister takes the decision about when to trigger Article 50 and start the formal and legal process of leaving the EU.

— David Cameron, "EU referendum outcome: PM statement, 24 June 2016". gov.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

Article 50

Since 2007, the process of withdrawal from the European Union has been governed by Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. No member state has ever left the EU.[a] Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union provides an invocation procedure whereby a member can notify the European Council and there is a negotiation period of up to two years, after which the treaties cease to apply - although a leaving agreement may be agreed by Qualified majority voting.[65] Unless the Council of the European Union unanimously agrees to extensions, the timing for the UK leaving under the article is two years from when the country gives official notice to the EU. The assumption is that new agreements will be negotiated during the two-year window, but there is no legal requirement that agreements have to be made.[66] Some aspects, such as new trade agreements, may be difficult to negotiate until after the UK has formally left the EU.[67] Under Article 50, the withdrawal must be in accordance with the member state's constitution, and uncertainty exists as to the constitutional requirements in the UK.

The EU Parliament debated the planned UK exit, and on 28 June 2016 passed a motion calling for the "immediate" triggering of Article 50. However there is no mechanism allowing the EU to invoke the article.[68] As long as the UK Government has not invoked Article 50, the UK stays a member of the EU; must continue to fulfil all EU-related treaties, including possible future agreements; and should legally be treated as a member. The EU has no framework to exclude the UK—or any member—as long as Article 50 is not invoked, and the UK does not violate EU laws.[69][70] However, if the UK were to breach EU law significantly, there are legal provisions to discharge the UK from the EU via Article 7, the so-called "nuclear option", which allows the EU to cancel membership of a state that breaches fundamental EU principles, a test that will be hard to pass.[71] Article 7 does not allow forced cancellation of membership, only denial of rights such as free trade, free movement and voting rights.

Alan Renwick of the Constitution Unit of University College London argues that Article 50 negotiations cannot be used to renegotiate the conditions of future membership and that Article 50 does not provide the legal basis of withdrawing a decision to leave.[60]

On the other hand, the constitutional lawyer and retired German Supreme Court judge Udo Di Fabio has stated[72] that

- The Lisbon Treaty does not forbid an exiting country to withdraw its application for leaving, because the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (article 56, paragraph 2) prescribes an initial notification procedure, a kind of period of notice. Before a contract under international law [such as the Lisbon Treaty], which had been agreed without specifying details of giving notice, can be effectively cancelled, it is required that the intention to do so is expressed 12 months in advance: in this matter there exists the principle of preserving existing agreements and international organisations. In this light, everything argues for the view that the declaration of the intention to leave would itself be, under EU law, not a notice of cancellation.

- Separate negotiations of the EU institutions with pro-EU regions [London, Scotland or Northern Ireland] would constitute a violation of the Lisbon Treaty, according to which the integrity of a member country is explicitly put under protection (article 4, paragraph 2).

A briefing note for the European Parliament (February 2016) states that a withdrawal from the EU ends, from then on, the application of the EU Treaties in the withdrawing state, although any national acts previously adopted for implementing or transposing EU law would remain valid until amended or repealed, and a withdrawal agreement would need to deal with phasing-out EU financial programmes. The note mentions that a member withdrawing from the EU would need to enact its own new legislation in any field of exclusive EU competence, and that complete isolation of a withdrawing state would be impossible if there is to be a future relationship between the former member and the EU, but that a withdrawal agreement could have transitional provisions for rights deriving from EU citizenship and other rights deriving from EU law that the withdrawal would otherwise extinguish.[73] The Common Fisheries Policy is one of the exclusive competences reserved for the European Union; others concern customs union, competition rules, monetary policy and concluding international agreements. [74]

Plans for invoking Article 50

Immediately after the referendum, Cameron declared his belief that the next Prime Minister should activate Article 50 and begin negotiations with the EU.[75] During a 27 June 2016 meeting, the Cabinet decided to establish a unit of civil servants, headed by senior Conservative Oliver Letwin, who would proceed with "intensive work on the issues that will need to be worked through in order to present options and advice to a new Prime Minister and a new Cabinet".[76]

Prime Minister Theresa May made it clear that discussions with the EU would not start in 2016. "I want to work with ... the European council in a constructive spirit to make this a sensible and orderly departure." she said. "All of us will need time to prepare for these negotiations and the United Kingdom will not invoke article 50 until our objectives are clear." In a joint press conference with May on 20 July, Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel supported the UK's position in this respect: "We all have an interest in this matter being carefully prepared, positions being clearly defined and delineated. I think it is absolutely necessary to have a certain time to prepare for that."[77]

In October 2016 the UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, announced that Article 50 would be triggered by "the first quarter of 2017".[78]

Possible need for parliamentary approval before invoking Article 50

Opinions differ on whether Article 50 notification can be given for the United Kingdom by the government exercising the royal prerogative without an explicit Act of Parliament to authorise it. The Constitution of the United Kingdom is unwritten and it operates on convention and legal precedent: this question is without precedent and so the legal position is arguably unclear. The Government argues that the use of prerogative powers to enact the referendum result is constitutionally proper and consistent with domestic law whereas the opposing view is that prerogative powers may not be used to set aside rights previously established by Parliament.[79]

One week before the referendum polling day (23 June), a House of Commons briefing paper titled EU Treaty change: the parliamentary process of bills, dated 15 June 2015, stated that, while ratification of international treaties is a matter of royal prerogative, the ratification of treaties amending existing EU treaties is controlled by a requirement for a prior act of Parliament; but the paper made no mention of notification of withdrawal from existing treaties.[80]A week after the result of the referendum was announced, a columnist for The Times, David Pannick QC, who has been a member of the House of Lords from November 2008,[81] posed the question whether parliamentary approval is needed before notification is given of the UK's intention to leave, and gave as his answer that an act of parliament is required.[82] At the end of July, Pannick appeared in the High Court representing one of the parties challenging the government's claim to notify without parliament's approval (Santos and Miller -v- Secretary of State).

Three distinct groups of citizens – one supported by crowd funding – have brought a case before the High Court of England and Wales to challenge the government's interpretation of the law.[83] Whatever the ruling of the High Court, it is assumed that an appeal will be made to the Supreme Court since the matter (the circumstances in which the royal prerogative may be used) is of great constitutional significance.[84]

Legal challenge: Santos and Miller -v- Secretary of State

Note: Listed in the Administrative Court's daily cause list[85] as "Santos and M.",[86] but published documents in the proceedings have also been headed with the names of the Applicants/Claimants in reverse order: "(1) Miller (2) Santos".[87]

On 19 July 2016, at a preliminary High Court hearing of a challenge to the government's claim that it could issue the Article 50 notification in accordance with the Lisbon Treaty and without Parliamentary approval (Santos and Miller, Applicants -v- Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, Respondent), lawyers for the government confirmed that the prime minister would not issue any such notification before the end of 2016.[88] In the court proceedings, the government contended that it would be constitutionally impermissible for the court to make a declaration, such as the one then being sought, in terms that, unless authorised by an act of Parliament, the government could not lawfully issue notification under Article 50 to withdraw the United Kingdom from the European Union. In support of this contention, the government referred to the Court's previous decision when rejecting a challenge to the validity of the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty after the passing of the European Union (Amendment) Act in June 2008 but without a referendum,[89][90] and stated that the declaration now being opposed would likewise trespass on proceedings in Parliament.[91]

At the full hearing in October, before three judges sitting as a divisional court (the Lord Chief Justice, the Master of the Rolls and Lord Justice Sales), Lord Pannick argued for the lead claimant (Miller) that notification under Article 50 would commit the UK to the removal of rights existing under the European Communities Act 1972 and later ratification acts, and that it is not open to the government, without Parliament's approval, to use the prerogative power to take action affecting rights which Parliament had recognised in that way.[92] An argument put for the "Expat" Interveners at the hearing was that by the 1972 act Parliament had conferred a legislative competence on the EU institutions, and in that way had changed the constitutional settlement in the UK.[93]

Responding in the opening submissions for the government, the Attorney-General (Jeremy Wright) outlined how the decision had been reached. In support of the contention that when passing the 2015 Act Parliament well knew of the Article 50 procedure for leaving the European Union if that was voted for in the referendum, he said that Parliament had previously dealt with it when the Lisbon Treaty was included in domestic law by the 2008 Act, and he took the court through the legislation dealing with the European Union and its predecessor, namely:

- European Communities Act 1972 (before the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties came into force in 1980)

- European Parliamentary Elections Act 1978

- European Communities (Amendment) Act 1986

- European Communities (Amendment) Act 1993

- European Union (Accessions) Act 1994

- European Parliamentary Elections Act 2002

- European Union (Amendment) Act 2008

- Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010

- European Union Act 2011

- European Union Referendum Act 2015.[94]

In further submissions for the government, the lead claimant's primary argument was said by Treasury Counsel to be that it is not open to the executive to use the prerogative power in such a way as to affect or change current economic law, principally statute law;[95] but the government contended that the leading case Attorney General v De Keyser's Royal Hotel meant that the question about the use of the royal prerogative depended on Parliament's legislative intention.[96] The treaty ratification provisions of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 were in force from 11 November 2010,[97] that is, after the Lisbon Treaty, including Article 50, was ratified for UK on 16 July 2008,[98] and had come into force on 1 December 2009.[99] While the Act describes "treaty" as an agreement between states, or between states and international organisations, which is binding under international law, including amendments to a treaty, and defines "ratification" as including acts (such as notification that domestic procedures have been completed) which establish as a matter of international law the United Kingdom's consent to be bound by the treaty, ratification of an amendment to a European Union treaty may involve compliance with the European Union (Amendment) Act 2008, and there are further provisions under the European Union Act 2011.[100] The Lord Chief Justice described the statutory procedure as "of critical importance".[101]

The hearing concluded on 18 October, when the Lord Chief Justice said the judges would take time to consider the matter and give their judgments as quickly as possible.[102] The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom has scheduled time in December for hearing an appeal after delivery of the divisional court's judgment.[103]

In the meantime, the applications of other parties challenging the government in legal proceedings in Northern Ireland's High Court were dismissed on 28 October, but the court was prepared to grant leave to appeal in respect of four out of the five issues. [104]

"Great Repeal Bill"

In the October 2016 interview at which Theresa May announced the March 2017 deadline for triggering Article 50, she also promised a "Great Repeal Bill", which would repeal the European Communities Act 1972 and restate in UK law all enactments previously in force under EU law. This bill will be introduced in the autumn 2016 parliamentary session and enacted before or during the Article 50 negotiations; it would not come into force until the date of exit. It would smooth the transition by ensuring that all laws remain in force until specifically repealed.[105]

Such a bill is likely to cause issues constitutionally in terms of the devolution settlements throughout the UK nations. The Scottish Government's approach to the "Great Repeal Bill" is that it would require legislative consent from the Scottish Parliament, as it will legislate on Scottish matters.[106] It is also in the Scotland Act 1998 that any legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament has to comply with European Law. Without an alteration to this, Holyrood will still need to follow European Law, or Westminster will likely follow convention to gain legislative consent from the Scottish Parliament to alter this aspect of the Scotland Act.

Negotiating positions

Various EU leaders have said that they will not start any negotiation before the UK formally invokes Article 50. Jean-Claude Juncker even ordered all members of the EU Commission not to engage in any kind of contact with UK parties regarding Brexit.[107] In an interview with the Austrian newspaper Der Standard on 31 October 2016 ahead of the Austrian presidential elections, Juncker stated that the point that agitated him (umtreibt) was that the British had not developed a sense of community with Europeans during 40 years of membership; Juncker denied that Brexit was a warning (Warnschuss) for the EU, envisaged developing an EU defence policy without the British after Brexit, and rejected the interviewer's proposal that the EU Commission should negotiate in such a way that Britain would be able to hold a second referendum, and rejected calls for EU reform before Britain had left the EU.[108]

On 29 June, European Council president Donald Tusk told the UK that they would not be allowed access to the European Single Market unless they accept its four freedoms of goods, capital, services, and people.[109] German Chancellor Angela Merkel said "We'll ensure that negotiations don't take place according to the principle of cherry-picking ... It must and will make a noticeable difference whether a country wants to be a member of the family of the European Union or not."[110]

The First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, stated that Scotland might refuse consent for legislation required to leave the EU,[111] though some lawyers argue that Scotland cannot block Brexit.[112]

Newly appointed PM Theresa May made it clear that negotiations with the EU required a "UK-wide approach". Speaking in Scotland on 15 July 2016, May offered the following comment. "I have already said that I won't be triggering article 50 until I think that we have a UK approach and objectives for negotiations – I think it is important that we establish that before we trigger article 50."[113]

According to the Daily Telegraph, the Department for Exiting the European Union spent over £250k on legal advice from top Government lawyers in two months and has plans to recruit more people. Nick Clegg said the figures showed the Civil Service was unprepared for the very complex negotiations ahead.[114]

Consequences of withdrawal for the UK

Relationship with remaining EU members

As a majority of UK voters have supported leaving the EU, its subsequent relationship with the remaining EU members could take several forms. A research paper presented to the UK Parliament proposed a number of alternatives to membership which would continue to allow access to the EU internal market. These include remaining in the European Economic Area (EEA) as a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member (alongside Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland), or seeking to negotiate bilateral terms more along the Swiss model with a series of interdependent sectoral agreements.[115] Britain has not negotiated a trade agreement since before 1973, and the government is looking to the private sector for assistance.[116]

Were the UK to join the EEA as an EFTA member, it would have to sign up to EU internal market legislation without being able to participate in its development or vote on its content. However, the EU is required to conduct extensive consultations with non-EU members beforehand via its many committees and cooperative bodies.[117][118] Some EU law originates from various international bodies on which non-EU EEA countries have a seat.

The EEA Agreement (EU and EFTA members except Switzerland) does not cover Common Agriculture and Fisheries Policies, Customs Union, Common Trade Policy, Common Foreign and Security Policy, direct and indirect taxation, and Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters, leaving EFTA members free to set their own policies in these areas;[119] however, EFTA countries are required to contribute to the EU Budget in exchange for access to the internal market.[120][121]

The EEA Agreement and the agreement with Switzerland cover free movement of goods, and free movement of people.[122][123] Many supporters of Brexit want to restrict freedom of movement;[124] however, an EEA Agreement would include free movement for EU and EEA citizens, as passport systems allow EEA institutions to access markets in EU Member States, for the most part, without having to establish subsidiaries in each EU Member State and incur the costs of full authorisation in those jurisdiction.[125] Others[who?] present ideas of a Swiss solution, that is tailor-made agreements between the UK and the EU, but EU representatives have claimed they would not support such a solution.[citation needed] The Swiss agreements contain free movement for EU citizens.[126] (The Swiss immigration referendum, February 2014 voted narrowly in favour of an end to the 'free movement' agreement, by February 2017. However, the bilateral treaties between Switzerland and the European Union are all co-dependent, if one is terminated then all are terminated. Consequently, should Switzerland choose unilaterally to cancel the 'free movement' agreement then all its agreements with the EU will lapse unless a compromise is found – as of July 2016, no such compromise was in sight).[127]

Several thousand British citizens resident in other EU countries have after the referendum applied for citizenship where they live, since they fear losing the right work there.[128]

Immigration

A Conservative MEP representing South East England, Daniel Hannan, predicted on BBC Newsnight that immigration from the European Union would not end after Brexit:[129] "Frankly, if people watching think that they have voted and there is now going to be zero immigration from the EU, they are going to be disappointed. ... you will look in vain for anything that the Leave campaign said at any point that ever suggested there would ever be any kind of border closure or drawing up of the drawbridge."[130]

In late July 2016, discussions were underway that might provide the UK with an exemption from the EU rules on refugees' freedom of movement for up to seven years. Senior UK government sources confirmed to The Observer that this was "certainly one of the ideas now on the table".[131] If the discussions led to an agreement, the UK – though not an EU member – would also retain access to the single market but would be required to pay a significant annual contribution to the EU. According to The Daily Telegraph the news of this possibility caused a rift in the Conservative Party: "Tory MPs have reacted with fury .... [accusing European leaders of] ... failing to accept the public's decision to sever ties with the 28-member bloc last month."[132]

Economic effects

Prior to the referendum, the UK treasury estimated that being in the EU has a strong positive effect on trade and as a result the UK's trade would be worse off if it left the EU.[133]

Supporters of withdrawal from the EU have argued that the cessation of net contributions to the EU would allow for some cuts to taxes and/or increases in government spending.[134] However, Britain would still be required to make contributions to the EU budget if it opted to remain in the European Free Trade Area.[120] The Institute for Fiscal Studies notes that the majority of forecasts of the impact of Brexit on the UK economy indicate that the government would be left with less money to spend even if it no longer had to pay into the EU.[135]

On 15 June 2016, Vote Leave, the official Leave campaign, presented its roadmap to lay out what would happen if Britain left the EU.[136] The blueprint suggested that Parliament would pass laws: Finance Bill to scrap VAT on tampons and household energy bills; Asylum and Immigration Control Bill to end the automatic right of EU citizens to enter Britain; National Health Service (Funding Target) Bill to get an extra 100 million pounds a week; European Union Law (Emergency Provisions) Bill; Free Trade Bill to start to negotiate its own deals with non-EU countries; and European Communities Act 1972 (Repeal) Bill to end the European Court of Justice's jurisdiction over Britain and stop making contributions to the EU budget.[136]

European experts from the World Pensions Council (WPC) and the University of Bath have argued that, beyond short-lived market volatility, the long term economic prospects of Britain remain high, notably in terms of country attractiveness and foreign direct investment: "Country risk experts we spoke to are confident the UK's economy will remain robust in the event of an exit from the EU. 'The economic attractiveness of Britain will not go down and a trade war with London is in no one's interest,' says M Nicolas Firzli, director-general of the World Pensions Council (WPC) and advisory board member for the World Bank Global Infrastructure Facility [...] Bruce Morley, lecturer in economics at the University of Bath, goes further to suggest that the long-term benefits to the UK of leaving the Union, such as less regulation and more control over Britain's trade policy, could outweigh the short-term uncertainty observed in the [country risk] scores."[137]

On 10 August the Institute for Fiscal Studies published a report funded by the Economic and Social Research Council which warned that Britain faced some very difficult choices as it couldn't retain the benefits of full EU membership whilst restricting EU migration. The IFS claimed the cost of reduced economic growth would cost the UK around £70Bn more than the £8Bn savings in membership fees. It did not expect new trade deals to make up the difference.[138]

Financial services: On 4 October 2016, the Financial Times assessed the potential effect of Brexit on banking. The City of London is world leading in financial services, especially in currency transactions including foreign exchange of euros. This position is enabled by the EU-wide "passporting" agreement for financial products. Should the passporting agreement expire in the event of a Brexit, the British financial service industry might lose up to 35,000 of its 1 million jobs, and the Treasury might lose 5 billion pounds annually in tax revenue. Indirect effects could increase these numbers to 71,000 job losses and 10 billion pounds of tax annually. The latter would correspond to about 2% of annual British tax revenue.[139]

By July 2016 the Senate of Berlin had sent invitation letters encouraging UK-based start-ups to re-locate to Berlin.[140] According to Anthony Browne of the British Banking Association, many major and minor banks may relocate outside the UK.[141]

Academic funding: UK universities rely on the EU for around 16% of their total research funding, and are disproportionately successful at winning EU-awarded research grants. This has raised questions about how such funding would be impacted by a British exit.[142][143] St George's, University of London professor and UKIP campaigner Angus Dalgleish pointed out that Britain paid much more into the EU research budget than it received, and that existing European collaborations such as CERN and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) began long before the Lisbon Treaty, adding that leaving the EU would not damage Britain's science.[144] London School of Economics emeritus professor (and founder of UKIP) Alan Sked pointed out that non-EU countries such as Israel and Switzerland signed agreements with the EU in terms of the funding of collaborative research and projects, and suggested that if Britain left the EU, Britain would be able to reach a similar agreement with the EU, pointing out that educated people and research bodies would easily find some financial arrangement during an at least 2-year transition period which was related to Article 50 of Treaty of European Union (TEU).[145] The UK government promised that a major type of EU research grant, Horizon 2020 funding, will be funded by the UK for their remaining duration after EU exit for UK researchers.[146] A July 2016 investigation by The Guardian suggested a large number of research projects in a wide range of fields had been hit after the referendum result. They reported that European partners were reluctant to employ British researchers due to uncertainties over funding.[147]

Scotland, London, and Gibraltar

The constitutional lawyer and retired German Supreme Court judge Udo Di Fabio has stated that separate negotiations of the EU institutions with pro-EU regions [London, Scotland or Northern Ireland] would constitute a violation of the Lisbon Treaty, according to which the integrity of a member country is explicitly put under protection (article 4, paragraph 2).[148]

Before the referendum, leading figures with a range of opinions regarding Scottish independence suggested that in the event the UK as a whole voted to leave the EU but Scotland as a whole voted to remain, a second Scottish independence referendum might be precipitated.[149][150] Former Labour Scottish First Minister Henry McLeish asserted that he would support Scottish independence under such circumstances.[151] In 2013, Scotland exported around three and a half times more to the rest of the UK than to the rest of the EU.[152] The pro-union organisation Scotland in Union has suggested that an independent Scotland within the EU would face trade barriers with a post-Brexit UK and face additional costs for re-entry to the EU.[152]

The majority of those living in London and Greater London voted for the UK to remain in the EU. Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said she had spoken to London Mayor Sadiq Khan about the possibility of remaining in the EU and said he shared that objective for London. A petition calling on Khan to declare London independent from the UK received tens of thousands of signatures.[153][154] Supporters of London's independence argued that London should become a city-state similar to Singapore, while remaining within the EU.[155][156][157] Khan admitted that complete independence was unrealistic, but demanded devolving more powers and autonomy for London.[158]

In 2015, Chief Minister of Gibraltar Fabian Picardo suggested that Gibraltar, which was ceded to Great Britain under the Treaty of Utrecht, would attempt to remain part of the EU in the event the UK voted to leave,[159] but reaffirmed that, regardless of the result, the territory would remain British.[160] In a letter to the UK Foreign Affairs Select Committee, he requested that Gibraltar be considered in negotiations post-Brexit.[161] Spain's foreign minister José García-Margallo said Spain would seek talks on Gibraltar, whose status is disputed, the "very next day" after a British exit from the EU.[162]

Borders with the Republic of Ireland and France

The Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom as a whole share, since the 1920s, a Common Travel Area without border controls. According to statements by Theresa May and Enda Kenny, it is intended to maintain this arrangement.[163] After Brexit, in order to prevent illegal migration across the open Northern Irish border into the United Kingdom, the Irish and British governments agreed in October 2016 on a plan whereby British border controls would be applied to Irish ports and airports. This would prevent a "hard border" arising between southern and northern Ireland.[164]

The Mayor of Saint-Quentin, Xavier Bertrand, stated in February 2016 that "If Britain leaves Europe, right away the border will leave Calais and go to Dover. We will not continue to guard the border for Britain if it's no longer in the European Union," indicating that the juxtaposed controls would end with a leave vote. French Finance Minister Emmanuel Macron also suggested the agreement would be "threatened" by a leave vote.[165] These claims have been disputed, as the Le Touquet 2003 treaty enabling juxtaposed controls was not an EU treaty, and would not be legally void upon leaving.[166]

After the Brexit vote, Xavier Bertrand asked François Hollande to renegotiate the Touquet agreement,[167] which can be terminated by either party with two years' notice.[168] Hollande rejected the suggestion, and said: "Calling into question the Touquet deal on the pretext that Britain has voted for Brexit and will have to start negotiations to leave the Union doesn't make sense." Bernard Cazeneuve, the French Interior Minister, confirmed there would be "no changes to the accord". He said: "The border at Calais is closed and will remain so."[169]

The implications for the island of Ireland's Single Electricity Market have yet to be made clear.

Consequences of withdrawal for the EU

Shortly after the referendum, the German parliament published an analysis on the consequences of a Brexit on the EU and specifically on the economic and political situation of Germany.[170] According to this, Britain is, after the United States and France, the third most important export market for German products. In total Germany exports goods and services to Britain worth about 120 billion euros annually, which is about 8% of German exports, with Germany achieving a trade surplus with Britain worth 36.3 billion euros (2014). Should a "hard Brexit" come to pass, the German exports would be subject to WTO customs and tariffs, which would particularly affect German car exports, where duties of about 10% would have to be paid to Britain. In total, 750,000 jobs in Germany depend upon export to Britain, while on the British side about 3 million jobs depend on export to the EU. The study emphasises however that the predictions on the economic effects of a Brexit are subject to significant uncertainty.

According to the Lisbon Treaty (2009), EU Council decisions by a qualified majority can only be blocked by if at least 4 members of the Council form a blocking minority. This rule was originally developed to prevent the three most populous members (Germany, France, Britain) from dominating the EU Council.[171] However, after a Brexit of the economically liberal British, the Germans and like-minded northern European countries (the Dutch, Scandinavians and Balts) would lose an ally and therefore also their blocking minority.[172] Without this blocking minority, other EU states could overrule Germany and its allies in questions of EU budget discipline or the recruitment of German banks to guarantee deposits in troubled southern European banks.[173]

With Brexit the EU would lose its second-largest economy, the country with the third-largest population and the financial centre of the world.[174] Furthermore the EU would lose its second-largest net contributor to the EU budget (2015: Germany 14.3 billion euros, United Kingdom 11.5 billion euros, France 5.5 billion euros).[175]

Thus, the departure of Britain would result in an additional financial burden for the remaining net contributors: Germany for example would have to pay an additional 4.5 billion euros for 2019 and again for 2020. In addition the UK would no longer be a shareholder in the European Investment Bank, in which only EU members can participate. Britain's share amounts to 16% which Britain would withdraw unless there is an EU treaty change.[176] After a Brexit, the EU would lose its strongest military power (next to France) including the British nuclear shield, and one of its two veto powers in the security council of the United Nations.

A report by Tim Oliver of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs expanded analysis of what a British withdrawal could mean for the EU: the report argues a UK withdrawal "has the potential to fundamentally change the EU and European integration. On the one hand, a withdrawal could tip the EU towards protectionism, exacerbate existing divisions, or unleash centrifugal forces leading to the EU's unravelling. Alternatively, the EU could free itself of its most awkward member, making the EU easier to lead and more effective."[177] Some authors also highlight the qualitative change in the nature of the EU membership after Brexit: "What the UK case has clearly shown in our view is that for the Union to be sustainable, membership needs to entail constant caretaking as far as individual members' contributions to the common good are concerned, with both rights and obligations."[178]

See also

- Template:Wikipedia books link

- Project Fear (British politics)

- Department for Exiting the European Union

- European Union law

- Euroscepticism in the United Kingdom

- Multi-speed Europe

- Referendums related to the European Union

- Causes of Brexit

- Frexit

- Grexit

- Nexit

Notes

- ^ Greenland left the EU in 1985, prior to the introduction of Article 50, and as an autonomous country within the Danish Realm, not as a sovereign member state.

References

- ^ a b "Brexit: PM to trigger Article 50 by end of March". BBC News. 2 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "Britain and the EU: A Brixit looms". The Economist. 21 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Hjelmgaard, Kim; Onyanga-Omara, Jane. "Explainer: The what, when and why of 'Brexit'". USA Today. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Stumbling towards the Brexit – EU opinion & policy debates – across languages". BlogActiv.eu. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ "Coining catchy 'Brexit' term helped Brits determine EU vote". Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ^ Mortimore, Roger. "Polling history: 40 years of British views on 'in or out' of Europe". The Conversation. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ a b Mortimore, Roger. "Polling history: 40 years of British views on 'in or out' of Europe". The Conversation. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ New Open Europe/ComRes poll: Failure to win key reforms could swing UK’s EU referendum vote openeurope.org, 16 December 2015.

- ^ "1967: De Gaulle says 'non' to Britain – again". BBC News. 27 November 1976. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Into Europe", Parliament website [1]

- ^ English text of EU Accession Treaty 1972, Cmnd. 7463.[2]

- ^ "1973: Britain joins the EEC". BBC News. 1 January 1973. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Alex May, Britain and Europe since 1945 (1999).

- ^ DAvis Butler. "The 1975 Referendum" (PDF). Eureferendum.com. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Research Briefings – The 1974–75 UK Renegotiation of EEC Membership and Referendum". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ a b Vaidyanathan, Rajini (4 March 2010). "Michael Foot: What did the 'longest suicide note' say?". BBC News Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Dury, Hélène. "Black Wednesday" (PDF). Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Tempest, Matthew (9 February 2005). "Treasury papers reveal cost of Black Wednesday". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "EU treaties". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ "EUROPA The EU in brief". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Wood, Nicholas (28 November 1994). "Goldsmith forms a Euro referendum party". The Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b "UK Election 1997". Politicsresources.net. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "10 key lessons from the European election results". The Guardian. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Matt Osborn (7 May 2015). "2015 UK general election results in full". The Guardian.

- ^ Nicholas Watt (29 June 2012). "Cameron defies Tory right over EU referendum: Prime minister, buoyed by successful negotiations on eurozone banking reform, rejects 'in or out' referendum on EU". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

David Cameron placed himself on a collision course with the Tory right when he mounted a passionate defence of Britain's membership of the EU and rejected out of hand an 'in or out' referendum.

- ^ Sparrow, Andrew (1 July 2012). "PM accused of weak stance on Europe referendum". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

Cameron said he would continue to work for 'a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU'.

- ^ "David Cameron 'prepared to consider EU referendum'". BBC News. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

Mr Cameron said ... he would 'continue to work for a different, more flexible and less onerous position for Britain within the EU'.

- ^ "David Cameron promises in/out referendum on EU". BBC News. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "David Cameron sets out EU reform goals". BBC News. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Spaventa, Eleanore. "Explaining the EU deal: the 'emergency brake'". Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ "Prime Minister sets out legal framework for EU withdrawal". UK Parliament. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The process for withdrawing from the European Union" (PDF). GOV.UK. Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, HM Government. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Jon Stone (13 April 2016). "Vote Leave designated as official EU referendum Out campaign".

- ^ "Leave.eu". Leave.eu. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Better Off Out". Better Off Out. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Conservatives In". Conservatives In. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Alan Johnson MP. "Labour in for Britain – The Labour Party". Labour.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Britain in Europe". Liberal Democrats. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Greens for a Better Europe". Green Party. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Home". Scientists for EU. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Environmentalists For Europe homepage". Environmentalists For Europe. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Universities for Europe". Universities for Europe. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Another Europe is Possible". Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ "EU referendum: BBC forecasts UK votes to leave". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "EU Referendum Results". Sky (United Kingdom). Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Hooton, Christopher (24 June 2016). "Brexit: Petition for second EU referendum so popular the government site's crashing". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Boult, Adam (26 June 2016). "Petition for second EU referendum attracts thousands of signatures". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: Petition for second EU referendum rejected". BBC News. 9 July 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "EU referendum results". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: David Cameron to quit after UK votes to leave EU". BBC. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "UKIP leader Nigel Farage stands down". BBC News. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "Exclusive: Britain 'could liberate Europe again' by voting for Brexit and sparking populist revolution". The Daily Telegraph. 22 May 2016.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip; Scammell, Rosie; Darroch, Gordon (8 July 2016). "Brexit causes resurgence in pro-EU leanings across continent". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Gordon Brown, "The key lesson of Brexit is that globalisation must work for all of Britain" in The Guardian, 29 June 2016.[3]

- ^ Independent (online), "Downing Street rejects Tony Blair’s call for second Brexit vote, saying he speaks only ‘for himself’".[4]

- ^ BBC News, "Tony Blair: Options must stay open on Brexit"

- ^ Jean-Claude Piris, The Constitution for Europe: A Legal Analysis (2006).[5]

- ^ Brexit: Tony Blair says there must be a second vote on UK's membership of EU The Independent

- ^ Tony Blair suggests second EU referendum: "Remain voters are not an elite" New Statesman

- ^ a b Renwick, Alan (19 January 2016). "What happens if we vote for Brexit?". The Constitution Unit Blog. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Wright, Ben. "Reality Check: How plausible is second EU referendum?". BBC. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Staunton, Denis (23 February 2016). "David Cameron: no second referendum if UK votes for Brexit". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Patrick Wintour (20 July 2016). "Cameron accused of 'gross negligence' over Brexit contingency plans". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: David Cameron to quit after UK votes to leave EU". BBC. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Article 50(3) of the Treaty on European Union.

- ^ "EU referendum: Would Brexit violate UK citizens' rights?". BBC News. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ editor, Patrick Wintour Diplomatic (22 July 2016). "UK officials seek draft agreements with EU before triggering article 50". Retrieved 12 October 2016 – via The Guardian.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Stone, Jon (28 June 2016). "Nigel Farage Mocked and Heckled by MEPs During Extraordinary Speech". Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "George Osborne: Only the UK can trigger Article 50". Al Jazeera.

- ^ Henley, Jon (26 June 2016). "Will article 50 ever be triggered?". The Guardian.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (25 June 2016). "What is Article 50 and why is it so central to the Brexit debate?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ FAZ Artikel: Zukunft-der-europaeischen-union Kopf-hoch

- ^ Eva-Maria Poptcheva, Article 50 TEU: Withdrawal of a Member State from the EU, Briefing Note for European Parliament.(Note: "The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the author and any opinions expressed therein do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.")[6]

- ^ EU Competences. [7]

- ^ Cooper, Charlie (27 June 2016). "David Cameron rules out second EU referendum after Brexit". The Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Proctor, Kate (27 June 2016). "Cameron sets up Brexit unit". Yorkshire Post. West Yorkshire, UK. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (20 July 2016). "Angela Merkel backs Theresa May's plan not to trigger Brexit this year". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: Theresa May to trigger Article 50 by end of March". BBC News. 2 October 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Judicial review litigation over the correct constitutional process for triggering Article 50 TEU". Lexology. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ EU Treaty change: the parliamentary process of bills (2015).[8]

- ^ Hansard, Lords, 3 November 2008

- ^ The Times, 30 June 2016

- ^ "Mishcons, Edwin Coe and heavyweight QCs line up as key Brexit legal challenge begins". Legal Week. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Brexit Article 50 Challenge to Quickly Move to Supreme Court". Bloomberg. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ RCJ daily cause list.

- ^ "Santos" in article at "Law and Lawyers".

- ^ As in, Secretary of State's Grounds of resistance, 2 September 2016

- ^ "Brexit move 'won't happen in 2016' Government tells High Court judge in legal challenge". London Evening Standard. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Telegraph 18 June 2008

- ^ BBC News, 17 July 2008

- ^ SSExEU, para.62

- ^ The Queen on the application of Santos and Miller, Applicants -v- Secretary of State for exiting the European Union, Respondent: Transcript, 13 October 2016, p.109-115.[9]

- ^ -: Transcript, 18 October 2016, p.31

- ^ -: Transcript, 17 October 2016, from p.60

- ^ -: Transcript, 17 October 2016, p.108

- ^ -: Transcript, 17 October 2016, p. 123

- ^ The Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (Commencement No. 3) Order 2010.[10]

- ^ BBC News 17 July 2008, UK ratifies the EU Lisbon Treaty

- ^ BBC News 17 January 2011, Q&A: The Lisbon Treaty

- ^ CRAG 2010, Explanatory Notes

- ^ -: Transcript, 18 October 2016, p. 5

- ^ -: Transcript, 18 October 2016, p.161

- ^ [11]| Michael Zander, Brexit in court, New Law Journal, 19 October 2016.

- ^ Full judgment, Agnew and others, Applying for leave to apply for judicial review -v- HM Government and SoS for Northern Ireland and SoS for Exiting the EU (Respondents).[12]

- ^ Mason, Rowena (2 October 2016). "Theresa May's 'great repeal bill': what's going to happen and when?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (3 October 2016). "UK and Scotland on course for great 'constitutional bust-up'". BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "No notification, no negotiation: EU officials banned from Brexit talks with Britain". 30 June 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Juncker on populist right-wingers: "I want to stand against these forces"". 31 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ Heffer, Greg (29 June 2016). "'It's not single market a la carte' Donald Tusk tells UK it's FREE MOVEMENT or nothing". Daily Express. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Merkel tells Britain no 'cherry-picking' in Brexit talks". Reuters. 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Could Scotland block Brexit?". Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Elliott; Mark. "Can Scotland block Brexit?". PublicLawForEveryone.com. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Brooks, Libby (15 July 2016). "May tells Sturgeon Holyrood will be 'fully engaged' in article 50 decision". London, UK. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Laura Hughes (9 September 2016). "Brexit department spends more than £250,000 on legal advice in just two months". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Leaving the EU – RESEARCH PAPER 13/42" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 1 July 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Parker; George (4 July 2016). "Britain turns to private sector for complex Brexit talks". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "EFTA Bulletin Decision Shaping in the European Economic Area" (PDF). European Free Trade Association. March 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Jonathan Lindsell (12 August 2013). "Fax democracy? Norway has more clout than you know". civitas.org.uk.

- ^ "The Basic Features of the EEA Agreement". European Free Trade Association. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ a b Glencross, Andrew (March 2015). "Why a British referendum on EU membership will not solve the Europe question". International Affairs. 91 (2): 303–17. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12236.

- ^ "EEA EFTA Budget". EFTA. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Free Movement of Capital", "EFTA". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Free Movement of Persons", "EFTA". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Grose, Thomas. "Anger at Immigration Fuels the UK's Brexit Movement", U.S. News & World Report, Washington, D.C., 16 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Brennand, David A.; Jackson, Carolyn H.; Lalone, Nathaniel W.; Robson, Neil; Sugden, Peter (24 June 2016). "Brexit: Implications for the Financial Services Industry". The National Law Review. Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Agreement with the Swiss Federation: free movement of persons". European Commission. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ EU tells Swiss no single market access if no free movement of citizens The Guardian, 3 July 2016

- ^ Huge increase in Britons seeking citizenship in EU states as Brexit looms

- ^ "Newsnight exchange with Brexit MEP Daniel Hannan". BBC News. 25 June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Lowyry, Nigel (25 June 2016). "Nigel Farage: Leave campaign pledges 'mistake', may not be upheld". iNews UK. Media Nusantara Citra. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Helm, Toby (24 July 2016). "Brexit: EU considers migration 'emergency brake' for UK for up to seven years". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Hughes, Laura (24 July 2016). "Tory MPs react with fury as EU leaders consider UK 'emergency brake' on free movement". The Telegraph. London, UK.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ The end of British austerity starts with Brexit J. Redwood, The Guardian, 14 April 2016

- ^ "Brexit and the UK's Public Finances" (PDF). Institute For Fiscal Studies (IFS Report 116). May 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b EU referendum: Vote Leave sets out post-Brexit plans BBC News, 15 June 2016

- ^ De Meulemeester, Claudia. "Country Risk: Experts Say UK economy Will Quickly Recover from Brexit Shock". Euromoney. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Steven Swinford (10 August 2016). "Britain could be up to £70billion worse off if it leaves the Single Market after Brexit, IFS warns". Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Claim 'hard Brexit' could cost UK £10bn in tax". Financial Times. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (9 July 2016). "Berlin is beckoning to Britain's startups. But will they leave London?". The Guardian.

- ^ Banks poised to relocate out of UK over Brexit, BBA warns

- ^ Cressey, Daniel (2016). "Academics across Europe join 'Brexit' debate". Nature. 530 (7588): 15–15. doi:10.1038/530015a.

- ^ Cressey, Daniel (2016). "Scientists say 'no' to UK exit from Europe in Nature poll". Nature. 531 (7596): 559–559. doi:10.1038/531559a.

- ^ Dalgleish, Angus (9 June 2016). "EU Referendum: Brexit 'will not damage UK research'". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Sked, Alan (3 March 2016). "Don't listen to the EU's panicking pet academics". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Cressey, Daniel. "UK government gives Brexit science funding guarantee". nature.com. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.20434. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ Sample, Ian (12 July 2016). "UK scientists dropped from EU projects because of post-Brexit funding fears". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Di Fabio, Udo (7 July 2016). "Future of the European Union - Chin up!". FAZ. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ Simons, Ned (24 January 2016). "Nicola Sturgeon Denies She Has 'Machiavellian' Wish For Brexit". The Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Simons, Ned (26 January 2016). "Scotland Will Quit Britain If UK Leaves EU, Warns Tony Blair". The Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Henry McLeish: I will back Scottish independence if UK leave EU against Scotland's wishes". The Herald. Glasgow. 10 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Scotland, 'Brexit' and the UK" (PDF). Scotland in Union. January 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "It's time for London to leave the UK". 24 June 2016.

- ^ "'Londependence' petition calls for London to join the EU on its own". 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Londoners want their own independence after Brexit result". The Washington Post. 24 June 2016.

- ^ "One expert argues that following Brexit, London needs to take back control".

- ^ Sullivan, Conor (24 June 2016). "Londoners dismayed at UK's European divorce" – via Financial Times.

- ^ "Sadiq Khan: Now London must 'take back control', 28 June 2016". london.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Swinford, Steven (14 April 2015). "Gibraltar suggests it wants to stay in EU in the event of Brexit". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ "Happy Birthday, Your Majesty". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Britain must include Gibraltar in post-Brexit negotiations, report says". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Spanish PM's anger at David Cameron over Gibraltar". BBC News. 16 June 2016.

- ^ "Britain does not want return to Northern Ireland border controls, says May". Irish Times. 26 July 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ "Irish Republic signals support for UK plan to avoid post-Brexit 'hard border'". Guardian. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Patrick Wintour (3 March 2016). "French minister: Brexit would threaten Calais border arrangement". The Guardian.

- ^ "Q&A: Would Brexit really move "the Jungle" to Dover?". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Xavier Bertrand a les accords du Touquet dans le viseur". Libération.

- ^ Treaty between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the French Republic concerning the Implementation of Frontier Controls at the Sea Ports of both Countries on the Channel and North Sea (PDF), The Stationery Office, 4 February 2003, cm6172, retrieved 5 July 2016,

This Treaty is concluded for an unlimited duration and each of the Contracting Parties may terminate it at any time by written notification ... The termination shall come into effect two years after the date of this notification.

- ^ Buchanan, Elsa (30 June 2016). "François Hollande rejects suspension of Le Touquet treaty at Calais despite UK Brexit". International Business Times. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ Andreas Koenig (27 June 2016). "Ökonomische Aspekte eines EU-Austritts des Vereinigten Königreichs (Brexit)" (PDF) (in German). Deutscher Bundestag. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ M. Chardon (1 January 2013). "Sperrminorität" (in German). Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ Holger Romann (25 August 2016). "Nach dem Brexit-Votum: EU-Wirtschaftspolitik - was geht da?" (in German). ARD. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ Dorothea Siems (18 June 2016). "Sperrminorität" (in German). Die Welt. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ "EU-Austritt des UK: Diese Folgen hat der Brexit für Deutschland und die EU" (in German). Merkur. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ Hendrik Kafsack (8 August 2016). "EU-Haushalt: Deutschland überweist das meiste Geld an Brüssel" (in German). FAZ. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ Reuters/dpa (10 September 2016). "Brexit wird teuer für Deutschland" (in German). FAZ. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|day=,|month=, and|deadurl=(help) - ^ Oliver, Tim L. "Europe without Britain". Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Torres, Francisco. "The Political Economy of Brexit: Why Making It Easier to Leave the Club Could Improve the EU". Intereconomics. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

Further reading

- Hobolt, Sara B. (7 September 2016). "The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent". Journal of European Public Policy. 23 (9): 1259–1277. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785. ISSN 1350-1763.

- Peers, Steve (2016). The Brexit: The Legal Framework for Withdrawal from the EU or Renegotiation of EU Membership. Oxford, U.K.: Hart Publishing. ISBN 9781849468749. OCLC 917161408.

External links

- Brexit at Curlie

- Gov UK – Department for Exiting the European Union

- BBC: "Brexit: What are the options?" (10 October 2016)

- Skeleton Argument of the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, and names of all parties in judicial review, for hearing in High Court, 13 and 17 October 2016

- Transcripts of High Court hearing in October 2016, Santos and M -v- Secretary of State

- Summary of judgment in N.I High Court, 28 October 2016, dismissing applications for judicial review.