Breaker Morant (film): Difference between revisions

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 1 as dead. #IABot (v1.2.6) |

|||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

[[Rotten Tomatoes]] gave ''Breaker Morant'' an average rating of 8.3/10 based on 18 reviews and also comments "Superbly executed in every area, the film is a memorable evocation of the hypocrisy of empire."<ref>[http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/breaker_morant/ "Breaker Morant (1980)"] on [[Rotten Tomatoes]]. Retrieved 24 July 2009.</ref> |

[[Rotten Tomatoes]] gave ''Breaker Morant'' an average rating of 8.3/10 based on 18 reviews and also comments "Superbly executed in every area, the film is a memorable evocation of the hypocrisy of empire."<ref>[http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/breaker_morant/ "Breaker Morant (1980)"] on [[Rotten Tomatoes]]. Retrieved 24 July 2009.</ref> |

||

The film also acted to stir debate on the ongoing effect and legacy of the trial with its anti-war theme. In one analysis of the film, D. L. Kershen comments: "''Breaker Morant'' tells the story of the court-martial of Harry Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton in South Africa in 1902. Yet, its overriding theme is war's evil. ''Breaker Morant'' is a beautiful anti-war statement—a plea for the end of the intrigues and crimes that war entails."<ref>[http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/etext/okla/kershen22.htm "Breaker Morant"] ''Oklahoma City University Law Review'' Volume 22, Number 1 (1997). Retrieved 24 July 2009.</ref> |

The film also acted to stir debate on the ongoing effect and legacy of the trial with its anti-war theme. In one analysis of the film, D. L. Kershen comments: "''Breaker Morant'' tells the story of the court-martial of Harry Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton in South Africa in 1902. Yet, its overriding theme is war's evil. ''Breaker Morant'' is a beautiful anti-war statement—a plea for the end of the intrigues and crimes that war entails."<ref>[http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/etext/okla/kershen22.htm "Breaker Morant"] {{wayback|url=http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/lpop/etext/okla/kershen22.htm |date=20090106034741 |df=y }} ''Oklahoma City University Law Review'' Volume 22, Number 1 (1997). Retrieved 24 July 2009.</ref> |

||

Another comments: "The clear issue of the film is accountability of soldiers in war for [[command responsibility|acts condoned by their superiors]]. Another issue, which I find particularly fascinating, concerns the fairness of the hearing. We would ask whether [[due process]] was present, after accounting for the exigencies of the battlefield. Does ''Breaker Morant'' demonstrate what happens when due process is not observed?"<ref>[http://pegasus.cc.ucf.edu/~pyle/pla4020/Breaker.html "Breaker Morant"] on the [[University of Central Florida]] website Retrieved 24 July 2009</ref> |

Another comments: "The clear issue of the film is accountability of soldiers in war for [[command responsibility|acts condoned by their superiors]]. Another issue, which I find particularly fascinating, concerns the fairness of the hearing. We would ask whether [[due process]] was present, after accounting for the exigencies of the battlefield. Does ''Breaker Morant'' demonstrate what happens when due process is not observed?"<ref>[http://pegasus.cc.ucf.edu/~pyle/pla4020/Breaker.html "Breaker Morant"] on the [[University of Central Florida]] website Retrieved 24 July 2009</ref> |

||

| Line 345: | Line 345: | ||

* [https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3713-breaker-morant-scapegoats-of-empire Criterion Collection essay] by Neil Sinyard |

* [https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3713-breaker-morant-scapegoats-of-empire Criterion Collection essay] by Neil Sinyard |

||

*[http://brightlightsfilm.com/kangaroo-court-on-bruce-beresfords-breaker-morant/#.Vpzm1fXnaTl "Kangaroo Court: On Bruce Beresford's 'Breaker Morant'"] ''[[Bright Lights Film Journal]]'' |

*[http://brightlightsfilm.com/kangaroo-court-on-bruce-beresfords-breaker-morant/#.Vpzm1fXnaTl "Kangaroo Court: On Bruce Beresford's 'Breaker Morant'"] ''[[Bright Lights Film Journal]]'' |

||

* [http://colsearch.nfsa.afc.gov.au/nfsa/search/display/display.w3p;adv=yes;group=;groupequals=;holdingType=;page=0;parentid=;query=4461;querytype=;rec=0;resCount=10 Breaker Morant] at the [[National Film and Sound Archive]] |

* [http://colsearch.nfsa.afc.gov.au/nfsa/search/display/display.w3p;adv=yes;group=;groupequals=;holdingType=;page=0;parentid=;query=4461;querytype=;rec=0;resCount=10 Breaker Morant]{{dead link|date=November 2016 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} at the [[National Film and Sound Archive]] |

||

* [http://australianscreen.com.au/titles/breaker-morant/ ''Breaker Morant''] at [[Australian Screen Online]] |

* [http://australianscreen.com.au/titles/breaker-morant/ ''Breaker Morant''] at [[Australian Screen Online]] |

||

*[http://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/breaker-morant ''Breaker Morant''] at Oz Movies |

*[http://www.ozmovies.com.au/movie/breaker-morant ''Breaker Morant''] at Oz Movies |

||

Revision as of 17:38, 7 November 2016

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (July 2016) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2015) |

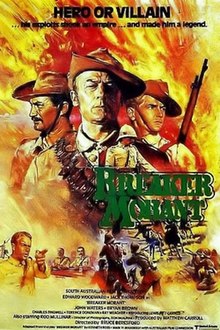

| Breaker Morant | |

|---|---|

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bruce Beresford |

| Screenplay by | Bruce Beresford Jonathan Hardy David Stevens |

| Produced by | Matt Carroll |

| Starring | Edward Woodward Jack Thompson |

| Cinematography | Donald McAlpine |

| Edited by | William M. Anderson |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Roadshow Entertainment New World Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | A$800,000[1] |

| Box office | $4,735,000 (Australia) $3.5 million[2] |

Breaker Morant is a 1980 Australian war- and trial film directed by Bruce Beresford, who also co-wrote based on Kenneth G. Ross' 1978 play of the same name.[3][4][5]

The film centres around the 1902 court martial of Lieutenants Harry Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton - one of the first war crimes prosecutions in British military history. Australians serving in the British Army during the Second Anglo-Boer War, Lts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton stood accused of murdering captured enemy combatants and an unarmed civilian in the Northern Transvaal. The film is notable for its exploration of the Nuremberg Defense, the politics of the death penalty, and the human cost of total war. As the trial unfolds, the events in question are shown in flashbacks.

In 1980, the film won ten Australian Film Institute Awards including: Best Film, Best Direction, Leading Actor, Supporting Actor, Screenplay, Art Direction, Cinematography, and Editing. It was also nominated for the 1980 Academy Award for the Best Writing (Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium).

Breaker Morant remains the movie with which Beresford is most identified[6] and has "hoisted the images of the accused officers to the level of Australian icons and martyrs."[7] In a 1999 interview, however, Beresford explained that Breaker Morant "never pretended for a moment" that the defendants were not guilty as charged. He had intended the film to explore how wartime atrocities can be "committed by people who appear to be quite normal." Beresford concluded that he was "amazed" that so many people see his film as being about "poor Australians who were framed by the Brits."[8]

Synopsis

Pretoria, South Africa, 1902. Major Charles Bolton (Rod Mullinar) is summoned to a meeting with Lord Kitchener (Alan Cassell). He is told that three officers of the Bushveldt Carbineers—Lieutenants Harry Morant (Edward Woodward), Peter Handcock (Bryan Brown), and George Witton (Lewis Fitz-Gerald) -- have been arrested and charged with murdering captured Boers and a German missionary. Explaining ominously that the Kaiser has protested diplomatically about the latter killing, Kitchener asks Major Bolton to appear for the prosecution. To the Major's visible dismay, he is told that witnesses which would help the defence have been sent to India and that the defence counsel is expected to give him no trouble.

Meanwhile, Major J. F. Thomas (Jack Thompson) meets Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton the day before he is to represent them in court. He tells them that he knows only the basic facts, which don't look good. A small town solicitor from New South Wales, Major Thomas explains that he has never handled anything except legal documents like wills. Lieut. Handcock quips, "Might come in handy."

As court martial proceedings begin the following morning, Major Thomas argues, because his clients are Australians, that only the Australian Army can court martial them. Unmoved, the president of the court martial, Lt.-Col. Denny, explains that the defendants may be tried for alleged crimes committed while serving under British command in the Bushveldt Carbineers. Without further ado, Denny reads the indictment. The three stand accused of the murder of a Boer prisoner named Visser and the subsequent shooting of six other captured Boers whose names are unknown. Furthermore, Lts. Morant and Handcock are also charged with the murder of the Reverend C.A.D. Heese.

Maj. Bolton begins by calling witnesses who describe a lack of discipline, drunkenness, widespread looting, and corruption among the Bushveldt Carbineers at Fort Edward. Maj. Thomas, however, manages to damage their credibility during cross examination. The testimony then turns to the shooting of Visser, which is shown in flashback.

On 5 April 1901, Lt. Morant's close friend, Captain Simon Hunt, had led a group of men to a farmhouse at Duiwelskloof intending to capture or kill Boer Commando Field Cornet Barend Viljoen. On arrival, the Carbineers found the farm swarming with far more armed men than expected. Captain Hunt was wounded, pinned down by enemy fire, and left behind when he ordered his men to retreat.

When the patrol returned to Fort Edward without Captain Hunt, Intelligence Corps Captain Alfred Taylor (John Waters) suggests Morant "avenge Captain Hunt". After returning to the farm and finding Captain Hunt's body mutilated with knives, Morant gave chase, ambushed Viljoen's men, and forced them to retreat with heavy losses. After capturing a Boer named Visser who was wearing Captain Hunt's jacket, an enraged Morant ordered his men to line up into a firing squad and shoot him. They obey his order.

Back in the courtroom, Maj. Thomas argues that standing orders existed to shoot "all Boers captured wearing khaki". To the shock of Maj. Thomas and his clients, Maj. Bolton explains that those orders only applied to Boers wearing British uniforms as a ruse of war. When Morant takes the witness stand and is grilled by Bolton, he defends the shooting of Visser by saying that he fought the Boers as they fought him. When asked which of the rules of engagement justifies shooting an unarmed prisoner, Morant shouts, in reference to the caliber of his rifle, "Rule 303." That night, Maj. Thomas angrily tells Morant that he was the best witness the prosecution has yet had. The following day, testimony turns to the shooting of the six Boers.

Captain Taylor testifies that, prior to his death, Captain Hunt had paid a visit to Kitchener's headquarters. Following Hunt's return to Fort Edward, Lt. Morant had brought in a group of Boers who had surrendered, only to be told by Captain Hunt that new orders from Kitchener, relayed through Col. Hubert Hamilton, decreed that no more prisoners were to be taken. Saying, "The gentlemen's war is over", Hunt had had the prisoners all shot while Morant watched. Captain Taylor testifies, however, that Morant had continued to bring prisoners in until after Captain Hunt had been killed. Afterwards, he always ordered his men to shoot them. On cross examination, Maj. Bolton damages Taylor by forcing him to admit that he is also awaiting court martial for shooting prisoners.

According to other witnesses, a group of six Boer guerrillas had approached Fort Edward after Captain Hunt's death, bearing white flags. Morant ordered them disarmed, lined them up, and had them shot. When one prisoner attacks Witton, he kills him.

In response, Maj. Thomas demands that Kitchener be summoned as a witness. He argues that, as his clients only followed orders, all charges must be dropped. Lt.-Col. Denny recoils at the suggestion that Kitchener, a man revered throughout the British Empire, would be capable of giving such criminal orders. Equally contemptuous of the idea, Maj. Bolton privately tells Maj. Thomas that, if Kitchener testifies and denies giving the orders, the defendants' lives will be doomed. He vainly urges Maj. Thomas not to insist.

In a private conversation, Kitchener tells Col. Hamilton that, when he had issued orders to take no prisoners, he was trying to break the Boer guerrillas by waging total war. Now, however, he is trying to win the hearts and minds of the Afrikaner people and arrange a peace conference. To this end, a few soldiers "have to be sacrificed" for the misdeeds of the whole British Army. He orders Col. Hamilton to testify in his place and, when asked for what to say, Kitchener comments, "I think you know what to do."

The following day, Col. Hamilton takes the stand and denies ever having spoken to Captain Hunt. An outraged Morant stands up and screams that the Colonel is a liar. Lt.-Col. Denny, however, comments that there will be no more talk of orders to shoot prisoners. Maj. Thomas, however, explains that Col. Hamilton's testimony is irrelevant. The fact is, his clients believed that such orders existed and thus cannot be held accountable for following them. The trial then turns to the murder of the Reverend Heese.

A Corporal Sharp testifies that, shortly before the massacre of the six Boers, Rev. Heese had passed through Fort Edward in a buggy. Shortly after his departure, Lt. Handcock had ridden up to Morant, spoken briefly to him, and then ridden off, looking "agitated", in the same direction as Rev. Heese. Maj. Thomas damages Sharp on cross examination by revealing his hatred of the defendants.

Upon taking the stand, Morant explains that Heese was under orders to never speak to prisoners while passing through Fort Edward and violated them. When Maj. Bolton asks why such orders existed, Morant explains, "It was for security reasons." When Morant had confronted the Reverend, he had been told that the prisoners had begged Heese to pray with them and that he could not refuse. Heese then left the Fort and was later found, shot to death, along the road. Bolton suggests that Heese was going to inform their commanding officer of Morant's plans to kill the prisoners and accuses Morant of ordering Handcock to silence him. Unmoved, Morant insists that his commanding officer already knew and suggests that he be recalled from India to testify. He smugly adds, "I don't mind waiting."

After Morant stands down, Maj. Thomas requests and is granted a brief recess to confer with Lt. Handcock before putting him on the stand. Late into the night, Maj. Thomas pleads with Handcock to tell him the truth, calling the Heese murder "the most serious charge." At last, Handcock opens up about his whereabouts.

The following morning, Handcock testifies that, when he left Fort Edward, he had travelled to the homes of two married Afrikaner women and slept with them. As Maj. Bolton eyes him, Maj. Thomas produces signed depositions from the women to confirm Handcock's story. The court and the prosecution accept the depositions without summoning the women to give evidence.

Later, in the prison courtyard, Lt. Witton wonders aloud about who really did kill Rev. Heese. Handcock smiles and says, "Me." To Witton's horror, Handcock explains that his visits to his "two lady friends" happened afterwards. When Witton asks whether Maj. Thomas knows, Morant explains that there is no reason for him to know. Morant explains that the Bushveldt Carbineers represent a new kind of warfare "for a new century". As the Boers do not wear uniforms, the enemy is everyone, including men, women, children, and even missionaries. That is why, after Rev. Heese had left the Fort, Morant had told Handcock that he believed that the Reverend was a Boer spy and had said that he was going towards Leydsdorp. A seething Handcock replied that anything could happen on the way there, had ridden after Heese, and shot him.

After a powerful summing up speech from Maj. Thomas, the defendants are found guilty of shooting the prisoners but acquitted of murdering Rev. Heese.

As they celebrate their probable evasion of the death penalty, Captain Taylor takes Morant aside and tells him that he and Handcock are almost certainly going to be shot. He offers to have a horse ready and says that many of the Highland Scots guards are sympathetic. He urges Morant to flee to Portuguese Mozambique, take ship from Lourenço Marques, and "see the world". Unmoved, Morant says, "I've seen it."

The next morning, all three defendants are sentenced to death, with Witton's commuted to "life in penal servitude". Desperate to save his clients, Maj. Thomas rushes to Kitchener's headquarters to demand a commutation. Upon arrival, he learns that Kitchener has already left. He is also told that both Whitehall and the Australian Government have expressed support for the verdict and sentences. Furthermore, there now will be a peace conference and every British and Commonwealth soldier will soon be going home.

The next morning, as Lt. Morant's poem Butchered to Make a Dutchmen's Holiday is recited in voiceover, both he and Lt. Handcock are led before a firing squad. Moments before being gunned down, Morant shouts, "Shoot straight, you bastards! Don't make a mess of it!" The final shot shows the bodies of both men being loaded into coffins.

Cast

|

|

Production

The movie was the second of two films Beresford intended to make for the South Australian Film Corporation. He wanted to make Breakout, about the Cowra Breakout, but could not find a script he was happy with so turned to the story of Breaker Morant.[1]

Funding came from the SAFC, the Australian Film Commission, the Seven Network and PACT Productions. The distributors, Roadshow, insisted that Jack Thompson be given a role.[1]

Historical Inaccuracy

Alleged German Pressure

In conversation with Maj. Bolton, Lord Kitchener states that Kaiser Wilhelm II has formally protested about the murder of Rev. Heese, whom he describes as German citizen. He elaborates that the German people support the Boer cause, that their elected representatives covet the gold and diamond mines of the Boer Republics, and that the British Government fears German entry into the ongoing conflict. This, Kitchener explains, is why Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton must be convicted at all cost.

According to South African historian Charles Leach, however, the widespread legend that the German Foreign Office protested about the case, "cannot be proved through official channels." Furthermore, "no personal or direct communication" between the Kaiser and his uncle, King Edward VII "has been found despite widespread legend that this was definitely the case." Lastly, questions raised in the House of Commons on 8 April 1902, were answered by an insistence that neither the War Office, the Foreign Office, or Lord Kitchener had received "any such communication on this subject" "on behalf of the German government".[9]

Under international law, the German Government had no grounds to protest. Despite being attached to the Berlin Missionary Society, Rev. Heese had been born in Cape Colony and, "was, technically speaking, a British, and not a German citizen".[9]

The scene does contain a kernel of truth, however. Leach writes, "Several eminent South African historians, local enthusiasts, and commentators share the opinion that had it not been for the murder of the Reverend Heese, none of the other Bushveldt Carbineers murders would have gone to trial."[9]

Only Three Defendants

Although only Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton are shown as being on trial, there were three other defendants.

- Lieutenant Henry Picton, a British-born Australian officer of the Bushveldt Carbineers, was charged with Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton with "committing the offense of murder" for delivering a coup de grace after the shooting of the wounded prisoner Floris Visser. Lieut. Picton was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to be Cashiered from the British armed forces.[10]

- Captain Alfred James Taylor, the Irish-born commander of military intelligence at Fort Edward, stood accused of the murder of six unarmed Afrikaner men and boys, the theft of their money and livestock, and the subsequent murder of a Bushveldt Carbineers Trooper. He was acquitted.[11]

- Maj. Robert W. Lenehan, the Australian Field Commander of the Bushveldt Carbineers, stood accused of covering up the murder of a Bushveldt Carbineers Trooper who had disapproved of shooting prisoners. The official charge was, "When on active service by culpable neglect failing to make a report which it was duty to make." Maj. Lenehan was found guilty and sentenced to be reprimanded.[12]

Role of Enlisted Men and Col. Hall

The enlisted men from the Fort Edward garrison who testify against Lieuts. Morant, Handcock, and Witton are depicted as motivated by personal grudges against their former officers. A prime example is Corporal Sharp, who expresses a willingness to walk across South Africa in order to serve in the defendants' firing squad. Other prosecution witnesses have been thrown out of the Bushveldt Carbineers by the defendants for looting, drunkenness, and other offenses. Furthermore, all are portrayed with British accents.

The officer commanding at Pietersburg, Col. Hall, is further depicted as having been fully aware and even complicit in the total war tactics of the Fort Edward garrison. He is also described as having been sent to India to prevent him from giving testimony favorable to the defense.

Surviving documents, however, tell a very different story. The arrest of all six defendants was actually ordered by Col. Hall in response to a letter he had received from the enlisted men at Fort Edward.

The letter, dated 4 October 1901, was written by BVC Trooper Robert Mitchell Cochrane, a former Justice of the Peace from Western Australia, and signed by 15 members of the Fort Edward garrison.[13][14]

After listing numerous murders and attempted murders of unarmed Boer prisoners, local civilians, and BVC personnel who disapproved, the letter concluded, "Sir, many of us are Australians who have fought throughout nearly the whole war while others are Africaners who have fought from Colenso till now. We cannot return home with the stigma of these crimes attached to our names. Therefore we humbly pray that a full and exhaustive inquiry be made by Imperial officers in order that the truth be elicited and justice done. Also we beg that all witnesses may be kept in camp at Pietersburg till the inquiry is finished. So deeply do we deplore the opprobrium which must be inseparably attached to these crimes that scarcely a man once his time is up can be prevailed to re-enlist in this corps. Trusting for the credit of thinking you will grant the inquiry we seek."[15]

Arrested at Fort Edward

During his conversation with Lieuts. Handcock and Witton in the prison courtyard, Morant alleges that the British Army has marked them for death "ever since they arrested us at Fort Edward". In reality, their arrests took place elsewhere.

In response to the letter written by Trooper Cochrane, Col. Hall summoned all Fort Edward officers and non-commissioned officers to Pietersburg on 21 October 1901. All were met by a party of mounted infantry five miles outside Pietersburg on the morning of 23 October 1901 and "brought into town like criminals". Lt. Morant was arrested after returning from leave in Pretoria, where he had gone to settle the affairs of his deceased friend Captain Hunt.[16]

Rejection of Deals for Leniency

In the film, the British military is determined to obtain the maximum penalty against the defendants.

According to Australian historians Margaret Carnegie and Frank Shields, however, Lieuts. Morant and Handcock rejected an offer of full immunity from prosecution in return for turning King's Evidence. Military prosecutors allegedly hoped to use them as witnesses against BVC Major Robert Lenehan, who was believed to have issued orders to take no prisoners.[17]

Towards the end of the film, Captain Taylor informs Morant that the British Army will never dare to prosecute him, as he really can implicate Kitchener in war crimes.

According to South African historian Andries Pretorius, the trial of Alfred Taylor was almost certainly saved for last because, "The prosecution must have been hoping," in vain for the accused officers, "to implicate Taylor." Their refusal to do so seems to have ensured that Taylor was not convicted at his own trial.[18]

Captain Hunt

In the film, BVC Captain Hunt is inaccurately depicted as having an Australian accent.

According to South African historian Charles Leach, Captain Hunt "was an Englishman, a former Lieutenant in Kitchener's Fighting Scouts, and a fine horseman." A surviving photograph of Hunt also reveals him to have been far younger than the actor who plays him onscreen.[19]

Critical response

Rotten Tomatoes gave Breaker Morant an average rating of 8.3/10 based on 18 reviews and also comments "Superbly executed in every area, the film is a memorable evocation of the hypocrisy of empire."[20]

The film also acted to stir debate on the ongoing effect and legacy of the trial with its anti-war theme. In one analysis of the film, D. L. Kershen comments: "Breaker Morant tells the story of the court-martial of Harry Morant, Peter Handcock, and George Witton in South Africa in 1902. Yet, its overriding theme is war's evil. Breaker Morant is a beautiful anti-war statement—a plea for the end of the intrigues and crimes that war entails."[21]

Another comments: "The clear issue of the film is accountability of soldiers in war for acts condoned by their superiors. Another issue, which I find particularly fascinating, concerns the fairness of the hearing. We would ask whether due process was present, after accounting for the exigencies of the battlefield. Does Breaker Morant demonstrate what happens when due process is not observed?"[22]

Bruce Beresford claimed the film was often misunderstood as the story of men railroaded by the British:

But that's not what it's about at all. The film never pretended for a moment that they weren't guilty. It said they are guilty. But what was interesting about it was that it analysed why men in this situation would behave as they had never behaved before in their lives. It's the pressures that are put to bear on people in war time... Look at all the things that happen in these countries committed by people who appear to be quite normal. That was what I was interested in examining. I always get amazed when people say to me that this is a film about poor Australians who were framed by the Brits.[23]

After the success of Breaker Morant, Beresford was offered dozens of Hollywood scripts including Tender Mercies, which he later directed. The 1983 film earned him his only Academy Award nomination for Best Director to date, even though 1989's Driving Miss Daisy, which he directed, won Best Picture. Beresford said that Breaker Morant was not that successful commercially:

Critically, it was important, which is a key factor, and it has kept being shown over the years. Whenever I am in Los Angeles, it's always on TV. I get phone calls from people who say, 'I saw your movie, could you do something for us?' But, they're looking at a [then] twenty-year-old movie. At the time it never had an audience. Nobody went anywhere in the world. It opened and closed in America in less than a week. And in London, I remember it had four days in the West End. Commercially, a disaster, but... It's a film that people talk about to me all the time.[23]

Box office

Breaker Morant grossed $A4,735,000 at the box office in Australia,[24] the equivalent of $16,809,250 in 2009 dollars.[needs update]

Legacy

Breaker Morant heavily influenced Australian New Wave war films such as Gallipoli (1981), The Lighthorsemen (1987), and the five-part TV series ANZACS (1985). Recurring themes of these films include the Australian identity, such as mateship and larrikinism, wartime loss of innocence, and the coming of age of the Australian nation.

Breaker Morant has also influenced scores of other films, especially those with themes involving war crimes trials, capital punishment, military prosecutions, and government cover-ups.

In the 1981 film Gallipoli, the character of Frank Dunne (Mel Gibson), an Irish-Australian drifter with a deep cynicism about the British Empire and a hatred for the "lofty bastards" of the British officer corps, is modeled on Lt. Peter Handcock.

The final moments of the 1984 Argentine film Camila show the two lead characters sitting in chairs as they are executed by firing squad and being thrown into the same coffin afterwards. This also is an homage to Breaker Morant.

The 1992 film A Few Good Men, centers on the court martial of two U.S. Marines accused of murdering a member of their unit at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Their defense counsel (Tom Cruise) attempts to prove that they acted under verbal orders from the base commander (Jack Nicholson).

The 2000 film, Rules of Engagement centers around the court martial of U.S. Marine Corps Colonel Terry Childers (Samuel L. Jackson) who stands accused of massacring unarmed protesters outside the U.S. Embassy in Yemen. As in Breaker Morant, the Colonel's defense lawyer (Tommy Lee Jones) finds himself at odds with the highest levels of Government. U.S. National Security Advisor Bill Sokal (Bruce Greenwood) is determined to salvage U.S. prestige in the Islamic World by ensuring that Col. Childers is convicted. Unlike Kitchener, however, Sokal is not covering up that the massacre was committed under orders. Instead, evidence is being buried that proves that some of the protesters were in fact armed, had shot first, and that Colonel Childers had only ordered the Marines guarding the Embassy to return fire after three of their comrades had been killed.

The award-winning 2000 television movie Nuremberg, which focuses on the Nuremberg Trials, is also influenced by Breaker Morant. In a particular homage to Beresford's film, the last letter of Hermann Goering (Brian Cox) to his wife is read in voiceover as he writes it in his cell shortly before taking poison to avoid the gallows. This was inspired by a similar scene involving Lt. Peter Handcock.

The 2002, American thriller High Crimes centers around the court martial of ex-Marine Ronald Chapman (Jim Caviezel), who stands accused of torturing and murdering a village full of civilians in El Salvador in 1988. As in Breaker Morant, the highest levels of Government are covering up that the massacre was committed under orders.

The 2011 film The Conspirator, directed by Robert Redford, centers around the 1865 military tribunal which tried the surviving assassins of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. The film's protagonist, former Union Army Colonel Frank Aiken (James McAvoy), is called upon to defend the sole female defendant, Mary Surratt (Robin Wright). Similar to Major Thomas, Aiken at first believes in his client's guilt, but slowly changes his mind. As a result of his fight for her life, Aiken is ostracized by his fellow Union veterans and repudiated by his fiancee (Alexis Bledel).

Satire

In 1989, the acclaimed British sitcom Blackadder Goes Forth, which is set in the British Army during World War I, aired an episode titled Corporal Punishment. In an episode containing numerous homages[citation needed] to Breaker Morant, the serial's protagonist Captain Edmund Blackadder (Rowan Atkinson), is court martialed for murdering "a helpless, innocent pigeon" and disobeying "some orders as well."

Desperate to avoid going over the top, the Captain fakes a series of communications problems. This culminates in the shooting of a carrier pigeon carrying orders to advance ("With 50,000 men getting killed a week, who's going to miss a pigeon?").

Unfortunately, the pigeon is revealed to have been the beloved pet of the Kitcheneresque Division Commander, General Melchett (Stephen Fry). Upon learning what has happened, an outraged Melchett is told that Blackadder has "been disobeying orders with a breathtaking impertinence."

The General responds, "I don't care if he's been rogering the Duke of York with a prize-winning leek. He shot my pigeon! Ahh! Ahh! Ahh!"[25]

The day before his court martial Blackadder meets his defense counsel, the mini-brained upper class twit Lieutenant George (Hugh Laurie). Having even less legal experience than Maj. Thomas, the Lieutenant admits that his uncle is a lawyer, but he isn't. Lieut. George's college actually voted him the least likely to complete a coherent sentence. Despite also commenting that the evidence says that Blackadder is "as guilty as a puppy sitting beside a pile of poo,"[26] Lieut. George sets out defend his client.

Certain than "any impartial judge" is bound to let him off, Blackadder is horrified to learn that the judge will be... General Melchett. During the reading of the indictment, Melchett repeatedly calls Captain Blackadder, "The Flanders Pigeon Murderer", and tells the clerk of court, "Clerk, hand me the black cap, shall you. I'll be needing that."

After humiliating himself and his client with an extremely moronic defense, Lieut. George sums up similarly to Maj. Thomas and argues that Captain Blackadder is "totally and utterly guilty... of nothing more than trying to do his duty under difficult circumstances."

Gen. Melchett snaps, "Nonsense. He's a hound and a rotter and he's going to be shot. However, before we proceed to the formality of sentencing the deceased -- I mean the defendant -- I think we'd all enjoy hearing the case for the prosecution."[27]

After the prosecution counsel calls General Melchett to the witness stand and reduces him to tears with questions about his beloved pigeon, the General gleefully sentences Captain Blackadder to "be taken from this place and suffer death by shooting tomorrow at dawn."

When asked whether he has anything to say, Blackadder quips, "Yes. Might I have an alarm call please?"

Like Captain Taylor, Blackadder's batman, Private Baldrick (Tony Robinson) visits him that night and offers to help him escape. Captain Blackadder is elated, until he learns that Baldrick's "cunning plan" is completely stupid. Instead of a saw, a chisel, a gun, a change of clothes, a Swiss passport, and a huge false moustache, Baldrick has brought a small wooden duck, a pencil, a miniature trumpet, and a Robin Hood costume.

Like Breaker Morant, the episode climaxes with Captain Blackadder being led in front of a firing squad. Unlike Lieuts. Morant and Handcock, however, the Captain is saved by a telegram reversing the verdict from Lieut. George's uncle, the new Minister of War, who knew Blackadder to be his nephew's friend.

Upon returning to his dugout, Blackadder learns to his outrage that Lieut. George and Pvt. Baldrick "got whammed" on a case of Scotch whiskey and forgot to telegram his uncle. Instantly vowing revenge, the Captain retaliates by volunteering Lieut. George and Pvt. Baldrick for a mission into no man's land code-named "Operation Certain Death".

Accolades

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| AACTA Award (1980 AFI Awards) |

Best Film | Matt Carroll | Won |

| Best Direction | Bruce Beresford | Won | |

| Best Screenplay, Original or Adapted | Won | ||

| Jonathan Hardy | Won | ||

| David Stevens | Won | ||

| Best Actor | Jack Thompson | Won | |

| Edward Woodward | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Lewis Fitz-Gerald | Nominated | |

| Bryan Brown | Won | ||

| Charles 'Bud' Tingwell | Nominated | ||

| Best Cinematography | Donald McAlpine | Won | |

| Best Editing | William M. Anderson | Won | |

| Best Sound | William Anderson | Won | |

| Jeanine Chiavlo | Won | ||

| Phil Judd | Won | ||

| Gary Wilkins | Won | ||

| Best Production Design | David Copping | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Anna Senior | Won | |

| Academy Award | Best Adapted Screenplay | Jonathan Hardy | Nominated |

| David Stevens | Nominated | ||

| Bruce Beresford | Nominated | ||

| Cannes Film Festival | Palme d'Or | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Jack Thompson | Won | |

| Golden Globe Award | Best Foreign Film | Bruce Beresford | Nominated |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle | Best Foreign Film | Won | |

| NBR Award | Top 10 Films | Won | |

| NYFCC Award | Best Foreign Language Film | 2nd place | |

Release

A DVD is available by REEL Corporation (2001) with a running time of 104 minutes. Image Entertainment released a Blu-ray Disc version of the film in the US on 5 February 2008 (107 minutes), including the documentary "The Boer War", a detailed account of the historical facts depicted in the film.

In 2015 the film was released by The Criterion Collection on both DVD and Blu-ray.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Stratton, David. The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, 1980 p.55

- ^ Corman, Roger & Jerome, Jim. How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, Muller, 1990. p.191

- ^ Subsequent to the film's release, Ross – who began writing under the name "Kenneth Ross" in order to set himself apart from other creative Australians known as "Ken Ross" – found that he must write under the name of "Kenneth G. Ross" in order to distinguish himself from that other, also famous, Kenneth Ross: the Scottish/American Kenneth Ross that was the scriptwriter for The Day of the Jackal.

- ^ Kit Denton's 1973 book The Breaker was not the source (see Ross' successful legal action for details).

- ^ Bennett, C., "Breaker Morant: a veldt Vietnam", The Age, (Friday, 4 July 1980), p.10.

- ^ "Kangaroo Court: On Bruce Beresford's Breaker Morant" Bright Lights Film Journal, April 30, 2013.

- ^ Charles Leach (2012), The Legend of Breaker Morant is Dead and Buried. A South African Version of the Bushveldt Carbineers in the Zoutpansberg, May 1901-April 1902, Leach Printers & Signs, Louis Trinchardt, South Africa. Page xxxii.

- ^ Phone interview with Bruce Beresford (15 May 1999) accessed 17 October 2012 wayback machine archive 9 September 2015

- ^ a b c Leach (2012), page 80.

- ^ Leach (2012), pages 105-113, 117, 203.

- ^ Leach (2012), pages 105-107.

- ^ Leach (2012), page 203.

- ^ Leach (2012), pages 98-101.

- ^ Arthur Davey (1987), Breaker Morant and the Bushveldt Carbineers, Second Series No. 18. Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town. Pages 78-82.

- ^ Leach (2012), page 101.

- ^ Leach (2012), pages 97-98.

- ^ Carnegie and Shields (1979), In Search of Breaker Morant, pages 124-125.

- ^ Leach (2012), page 189.

- ^ Leach (2012), page 27.

- ^ "Breaker Morant (1980)" on Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "Breaker Morant" Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma City University Law Review Volume 22, Number 1 (1997). Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "Breaker Morant" on the University of Central Florida website Retrieved 24 July 2009

- ^ a b Malone. Phone interview with Bruce Beresford (15 May 1999) accessed 17 October 2012

- ^ "Film Victoria – Australian Films at the Australian Box Office" Archived 2011-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blackadder: The Whole Damn Dynasty (1998), Penguin Books. Page 369.

- ^ "Blackadder (1998), page 371.

- ^ Blackadder (1998), page 374.

Bibliography

- Ross, K.G., Breaker Morant: A Play in Two Acts, Edward Arnold, (Melbourne), 1979. ISBN 0-7267-0997-2

- Ross, Kenneth (26 February 2002). "The truth about Harry". The Age.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Written on the hundredth anniversary of Morant's execution and the twenty-fourth anniversary of the first performance of his play. Article was reprinted in The Sydney Morning Herald on the same date.

External links

- Breaker Morant at IMDb

- Breaker Morant at AllMovie

- Criterion Collection essay by Neil Sinyard

- "Kangaroo Court: On Bruce Beresford's 'Breaker Morant'" Bright Lights Film Journal

- Breaker Morant[permanent dead link] at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Breaker Morant at Australian Screen Online

- Breaker Morant at Oz Movies

- Breaker Morant at the British Film Institute

- 1980 films

- 1980s drama films

- 1980s historical films

- 1980s war films

- 1980s biographical films

- Australian films

- Australian drama films

- Australian war films

- Australian historical films

- British Empire war films

- Legal films

- Military courtroom films

- Second Boer War films

- Films set in South Africa

- Films based on plays

- War films based on actual events

- Films about war crimes trials

- Films based on works by Australian writers

- Films about capital punishment

- Films directed by Bruce Beresford

- Films shot in Adelaide

- Films shot in Flinders Ranges

- Films set in 1901

- Films set in 1902