Bushfires in Australia: Difference between revisions

JarrahTree (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 82.13.4.90 (talk) to last version by HiLo48 |

add attribution for licensed material |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

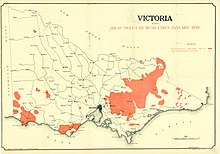

[[File:Black Friday 1939.jpg|thumb|Extent of the 1939 [[Black Friday bushfires]] in Victoria]] |

[[File:Black Friday 1939.jpg|thumb|Extent of the 1939 [[Black Friday bushfires]] in Victoria]] |

||

Large bushfires continued throughout the 20th Century. The [[Black Friday bushfires]] of 1939 were particularly devastating for the State of Victoria, when an area of almost two million hectares was burned, killing 71 people, and wiping out whole townships, along with many sawmills and thousands of sheep, cattle and horses: |

Large bushfires continued throughout the 20th Century. The [[Black Friday bushfires]] of 1939 were particularly devastating for the State of Victoria, when an area of almost two million hectares was burned, killing 71 people, and wiping out whole townships, along with many sawmills and thousands of sheep, cattle and horses: |

||

{{quote|[F]lames leapt large distances, giant trees were blown out of the ground by fierce winds and large pieces of burning bark (embers) were carried for kilometres ahead of the main fire front, starting new fires in places that had not previously been affected by flames... The townships of Warrandyte, Yarra Glen, Omeo and Pomonal were badly damaged. Intense fires burned on the urban fringe of Melbourne in the Yarra Ranges east of Melbourne, affecting towns including Toolangi, Warburton and Thomson Valley. The alpine towns of Bright, Cudgewa and Corryong were also affected, as were vast areas in the west of the state, in particular Portland, the Otway Ranges and the Grampians. The bushfires also affected the Black Range, Rubicon, Acheron, Noojee, Tanjil Bren, Hill End, Woods Point, Matlock, Erica, Omeo, Toombullup and the Black Forest. Large areas of state forest, containing giant stands of Mountain Ash and other valuable timbers, were killed. Approximately 575,000 hectares of reserved forest, and 780,000 hectares of forested Crown land were burned. The intensity of the fire produced huge amounts of smoke and ash, with reports of ash falling as far away as New Zealand. |

{{quote|[F]lames leapt large distances, giant trees were blown out of the ground by fierce winds and large pieces of burning bark (embers) were carried for kilometres ahead of the main fire front, starting new fires in places that had not previously been affected by flames... The townships of Warrandyte, Yarra Glen, Omeo and Pomonal were badly damaged. Intense fires burned on the urban fringe of Melbourne in the Yarra Ranges east of Melbourne, affecting towns including Toolangi, Warburton and Thomson Valley. The alpine towns of Bright, Cudgewa and Corryong were also affected, as were vast areas in the west of the state, in particular Portland, the Otway Ranges and the Grampians. The bushfires also affected the Black Range, Rubicon, Acheron, Noojee, Tanjil Bren, Hill End, Woods Point, Matlock, Erica, Omeo, Toombullup and the Black Forest. Large areas of state forest, containing giant stands of Mountain Ash and other valuable timbers, were killed. Approximately 575,000 hectares of reserved forest, and 780,000 hectares of forested Crown land were burned. The intensity of the fire produced huge amounts of smoke and ash, with reports of ash falling as far away as New Zealand.<ref name="Black Friday 1939"/>}} |

||

The event followed a series of extreme heatwaves that were accompanied by strong northerly winds, after a very dry six months. Melbourne hit 45.6 degrees and Adelaide 46.1. In NSW, Bourke suffered 37 consecutive days above 38 degrees and Menindee hit a record 49.7 degrees on January 10. Sydney was ringed to the north, south and west by bushfires - from Palm Beach and Port Hacking to the Blue Mountains.<ref>[https://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/lessons-learnt-and-perhaps-forgotten-from-australia-s-worst-fires-20190108-p50qol.html Lessons learnt (and perhaps forgotten) from Australia's 'worst fires']; smh.com.au; 11 Jan 2019</ref> ''The Argus'' reported that on 15 January, fierce winds spread fire to almost evert important area of the state, killing four, and burning in major fronts on Sydney's suburban fringes and hitting the south coast and inland - at Penrose, Wollongong, Nowra, Bathurst, Ulladulla and Mittagong: "hundreds of houses and thousands of head of stock and poultry were destroyed and thousands of acres of grazing land".<ref>Bush Fires Over Wide Area]; ''The Argus''; 16 Jan 1939</ref> |

The event followed a series of extreme heatwaves that were accompanied by strong northerly winds, after a very dry six months. Melbourne hit 45.6 degrees and Adelaide 46.1. In NSW, Bourke suffered 37 consecutive days above 38 degrees and Menindee hit a record 49.7 degrees on January 10. Sydney was ringed to the north, south and west by bushfires - from Palm Beach and Port Hacking to the Blue Mountains.<ref>[https://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/lessons-learnt-and-perhaps-forgotten-from-australia-s-worst-fires-20190108-p50qol.html Lessons learnt (and perhaps forgotten) from Australia's 'worst fires']; smh.com.au; 11 Jan 2019</ref> ''The Argus'' reported that on 15 January, fierce winds spread fire to almost evert important area of the state, killing four, and burning in major fronts on Sydney's suburban fringes and hitting the south coast and inland - at Penrose, Wollongong, Nowra, Bathurst, Ulladulla and Mittagong: "hundreds of houses and thousands of head of stock and poultry were destroyed and thousands of acres of grazing land".<ref>Bush Fires Over Wide Area]; ''The Argus''; 16 Jan 1939</ref> |

||

After the bushfires, Victoria convened a Royal Commission. Judge Leonard Stretton was instructed to inquire into the causes of the fires, and consider the measures taken to prevent the fires and to protect life and property. He made seven major recommendations to improve forest and fire management, and planned burning became an official fire management practice.<ref> |

After the bushfires, Victoria convened a Royal Commission. Judge Leonard Stretton was instructed to inquire into the causes of the fires, and consider the measures taken to prevent the fires and to protect life and property. He made seven major recommendations to improve forest and fire management, and planned burning became an official fire management practice.<ref name="Black Friday 1939">{{cite web |title=Black Friday 1939 |url=https://www.ffm.vic.gov.au/history-and-incidents/black-friday-1939 |publisher=Forest Fire Management Victoria |accessdate=19 January 2020 |language=en |date=27 February 2017}} [[File:CC-BY icon.svg|50px]] Material was copied from this source, which is available under a [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License].</ref> |

||

=== Northern Australia === |

=== Northern Australia === |

||

Revision as of 14:41, 19 January 2020

Bushfires in Australia are a widespread and regular occurrence that have contributed significantly to moulding the nature of the continent over millions of years. Eastern Australia is one of the most fire-prone regions of the world, and its predominant eucalypt forests have evolved to thrive on the phenomenon of bushfire.[1] However the blazes can cause significant property damage and loss of both human and animal life. Bushfires have killed approximately 800 people in Australia since 1851[2] and millions of animals.

The most destructive fires are usually preceded by extreme high temperatures, low relative humidity and strong winds, which combine to create ideal conditions for the rapid spread of fire.[3] Severe fire storms are often named according to the day on which they peaked, including the five most deadly blazes: Black Saturday 2009 in Victoria (173 people killed, 2000 homes lost); Ash Wednesday 1983 in Victoria and South Australia (75 dead, nearly 1900 homes); Black Friday 1939 in Victoria (71 dead, 650 houses destroyed), Black Tuesday 1967 in Tasmania (62 people and almost 1300 homes); and the Gippsland fires and Black Sunday of 1926 in Victoria (60 people killed over a two month period.[4] Other major conflagrations include the 1851 Black Thursday bushfires, the 2006 December bushfires, the 1974-75 fires, and the ongoing 2019–20 bushfires.[5] In January 2020, it was estimated that over 1.25 billion animals have died in the 2019-2020 Australian bushfire season.[6]

The gradual drying of the Australian continent over the last 15 million years has produced an ecology and environment prone to fire, which has resulted in many specialised adaptations amongst flora and fauna. Some of the country's flora has evolved to rely on bushfires for reproduction. Aboriginal Australians used to use fire to clear grasslands for hunting and to clear tracks through dense vegetation, and European settlers have also had to adapt to using fire to enhance agriculture and forrest management since the 19th century. Fire and forest management has evolved again through the 20th and 21st centuries with the spread of national parks and nature reserves, while post-industrial global warming is predicted to continue increasing the frequency of blazes.[7]

History

Before European settlement

According to Tim Flannery (The Future Eaters), fire is one of the most important forces at work in the Australian environment. Some plants have evolved a variety of mechanisms to survive or even require bushfires (possessing epicormic shoots or lignotubers that sprout after a fire, or developing fire-resistant or fire-triggered seeds), or even encourage fire (eucalypts contain flammable oils in the leaves) as a way to eliminate competition from less fire-tolerant species.[8] Early European explorers of the Australian coastline noted extensive bushfire smoke. Abel Janszoon Tasman's expedition saw smoke drifting over the coast of Tasmania in 1642 and noted blackened trunks and baked earth in the forests. While charting the east coast in 1770, Captain Cook's crew saw autumn fires in the bush burning on most days of the voyage.[9]

The fires would have been caused by both natural phenomenon and human hands. Aborigines in many regions set fire to grasslands in the hope of producing lusher grass to fatten kangaroos and other game and, at certain times of year, burned fire breaks as a precaution against bushfire.[10] Fire-stick farming was also used to facilitate hunting and to promote the growth of bush potatoes and other edible ground-level plants. In central Australia, they used fire in this way to manage their country for thousands of years.[11]

Flannery writes that "The use of fire by Aboriginal people was so widespread and constant that virtually every early explorer in Australia makes mention of it. It was Aboriginal fire that prompted James Cook to call Australia 'This continent of smoke'." However, he goes on to say: "When control was wrested from the Aborigines and placed in the hands of Europeans, disaster resulted."[12] Fire suppression became the dominant paradigm in fire management leading to a significant shift away from traditional burning practices. A 2001 study found that the disruption of traditional burning practices and the introduction of unrestrained logging meant that many areas of Australia were now prone to extensive wildfires especially in the dry season.[13] A similar study in 2017 found that the removal of mature trees by Europeans since they began to settle in Australia may have triggered extensive shrub regeneration which presents a much greater fire fuel hazard.[14] Another factor was the introduction of gamba grass imported into Queensland as a pasture grass in 1942, and planted on a large scale from 1983. This can fuel intense bushfires, leading to loss of tree cover and long-term environmental damage.[15][16]

Colonial era

Australia's hot, arid climate and wind-driven bushfires were a new and frightening phenomenon to the European settlers of the colonial era. The devastating Victorian bushfires of 1851, remembered as the Black Thursday bushfires, burned in a chain from Portland to Gippsland, and sent smoke billowing across the Bass Strait to north west Tasmania, where terrified settlers huddled around candles in their huts under a blackened afternoon sky.[17] The fires covered five million hectares (around one quarter of what is now the state of Victoria). Portland, Plenty Ranges, Westernport, the Wimmera and Dandenong districts were badly hit, and around 12 lives were recorded lost, along with one million sheep and thousands of cattle.[18]

New arrivals from the wetter climes of Britain and Ireland learned painful lessons in fire management and the European farmers slowly began to adapt - growing green crops around their haystacks and burning fire breaks around their pastures, and becoming cautious about burn offs of wheatfield stubble and ringbarked trees.[19] But major fire events persisted, including South Gippsland's 1898 Red Tuesday bushfires that burned 260,000 hectares and claimed twelve lives and more than 2,000 buildings.[20]

Since Federation

Large bushfires continued throughout the 20th Century. The Black Friday bushfires of 1939 were particularly devastating for the State of Victoria, when an area of almost two million hectares was burned, killing 71 people, and wiping out whole townships, along with many sawmills and thousands of sheep, cattle and horses:

[F]lames leapt large distances, giant trees were blown out of the ground by fierce winds and large pieces of burning bark (embers) were carried for kilometres ahead of the main fire front, starting new fires in places that had not previously been affected by flames... The townships of Warrandyte, Yarra Glen, Omeo and Pomonal were badly damaged. Intense fires burned on the urban fringe of Melbourne in the Yarra Ranges east of Melbourne, affecting towns including Toolangi, Warburton and Thomson Valley. The alpine towns of Bright, Cudgewa and Corryong were also affected, as were vast areas in the west of the state, in particular Portland, the Otway Ranges and the Grampians. The bushfires also affected the Black Range, Rubicon, Acheron, Noojee, Tanjil Bren, Hill End, Woods Point, Matlock, Erica, Omeo, Toombullup and the Black Forest. Large areas of state forest, containing giant stands of Mountain Ash and other valuable timbers, were killed. Approximately 575,000 hectares of reserved forest, and 780,000 hectares of forested Crown land were burned. The intensity of the fire produced huge amounts of smoke and ash, with reports of ash falling as far away as New Zealand.[21]

The event followed a series of extreme heatwaves that were accompanied by strong northerly winds, after a very dry six months. Melbourne hit 45.6 degrees and Adelaide 46.1. In NSW, Bourke suffered 37 consecutive days above 38 degrees and Menindee hit a record 49.7 degrees on January 10. Sydney was ringed to the north, south and west by bushfires - from Palm Beach and Port Hacking to the Blue Mountains.[22] The Argus reported that on 15 January, fierce winds spread fire to almost evert important area of the state, killing four, and burning in major fronts on Sydney's suburban fringes and hitting the south coast and inland - at Penrose, Wollongong, Nowra, Bathurst, Ulladulla and Mittagong: "hundreds of houses and thousands of head of stock and poultry were destroyed and thousands of acres of grazing land".[23]

After the bushfires, Victoria convened a Royal Commission. Judge Leonard Stretton was instructed to inquire into the causes of the fires, and consider the measures taken to prevent the fires and to protect life and property. He made seven major recommendations to improve forest and fire management, and planned burning became an official fire management practice.[21]

Northern Australia

In the last ten years or so, government licenses have been granted to fire-prevention programs on Aboriginal lands in northern Australia. In this area Aboriginal traditions, which reduce the undergrowth that can fuel bigger blazes, revolve around the monsoon. Land is burned patch by patch using "cool" fires in targeted areas during the early dry season, between March and July.[24] These defensive burning programs began in the 1980s and 1990s when Aboriginal groups moved back onto their native lands. Since this process began, destructive bushfires in northern Australia have burned 57% fewer acres in 2019 than they did on average in the years from 2000 to 2010, the decade before the program started.[25]

Oliver Costello from the national Indigenous Firesticks Alliance says that in southern Australia, Aboriginal knowledge systems of fire management are less valued than in the north. In the Kimberley area, the Land council applies local resources and holds community fire planning meetings to ensure the correct people are doing the burning. Burn lines are approved by the group but Indigenous rangers set the fires, backed up by modern technology involving constant weather readings and taking into account the conditions of the day. Costello points out that northern Australia has developed a collaborative infrastructure for 'cultural burning' but notes that: “There’s no investment really outside of northern Australia Indigenous fire management of any significance."[26]

Factors and causes

Ignition

In recent times most major bush fires have been started in remote areas by dry lightning[27][28] or by electric power lines being brought down or arcing in high winds. Many fires are as a result of either deliberate arson or carelessness, however these fires normally happen in readily accessible areas and are rapidly brought under control. Man-made events include arcing from overhead power lines, arson, accidental ignition in the course of agricultural clearing, grinding and welding activities, campfires, cigarettes and dropped matches, sparks from machinery, and controlled burn escapes. They spread based on the type and quantity of fuel that is available. Fuel can include everything from trees, underbrush and dry grassy fields to homes. Wind supplies the fire with additional oxygen pushing the fire across the land at a faster rate.

Large, violent wildfires can generate winds of their own, called fire whirls. Fire whirls are like tornadoes and result from the vortices created by the fire's heat. When these vortices are tilted from horizontal to vertical, this creates fire whirls. These whirls have been known to hurl flaming logs and burning debris over considerable distances.[29]

Some reports indicate that a changing climate could also be contributing to the ferocity of the 2019–20 fires with hotter, drier conditions making the country's fire season longer and much more dangerous.[30] Strong winds also promote the rapid spread of fires by lifting burning embers into the air. This is known as spotting and can start a new fire up to 40 km downwind from the fire front.[31] In the Northern Territory fires can also be spread by black kites, whistling kites and brown falcons. These birds have been spotted picking up burning twigs, flying to areas of unburned grass and dropping them to start new fires there. This exposes their prey attempting to flee the blazes: small mammals, birds, lizards, and insects.[32]

Topography

Bushfires in Australia are generally described as uncontrolled, non-structural fires burning in a grass, scrub, bush, or forested area. The nature of the fire depends somewhat on local topography. Hilly/mountainous fires burn in areas which are usually densely forested. The land is less accessible and not conducive to agriculture, thus many of these densely forested areas have been saved from deforestation and are protected by national, state and other parks. The steep terrain increases the speed and intensity of a firestorm. Where settlements are located in hilly or mountainous areas, bushfires can pose a threat to both life and property. Flat/grassland fires burn along flat plains or areas of small undulation, predominantly covered in grasses or scrubland. These fires can move quickly, fanned by high winds in flat topography, and they quickly consume the small amounts of fuel/vegetation available. These fires pose less of a threat to settlements as they rarely reach the same intensity seen in major firestorms as the land is flat, the fires are easier to map and predict, and the terrain is more accessible for firefighting personnel. Many regions of predominantly flat terrain in Australia have been almost completely deforested for agriculture, reducing the fuel loads which would otherwise facilitate fires in these areas.

Climate change

Australia's climate has warmed by more than one degree Celsius over the past century, causing an increase in the frequency and intensity of heatwaves and droughts.[33] Eight of Australia's ten warmest years on record have occurred since 2005.[34] A study in 2018 conducted at Melbourne University found that the major droughts of the late 20th century and early 21st century in southern Australia are "likely without precedent over the past 400 years".[35] Across the country, the average summer temperatures have increased leading to record-breaking hot weather,[36] with the early summer of 2019 the hottest on record.[37] 2019 was also Australia's driest ever year since 1900 with rainfall 40% lower than average.[38]

Heatwaves and droughts dry out the undergrowth and create conditions that increase the risk of bushfires. This has become worse in the last 30 years.[39] Since the mid-1990s, southeast Australia has experienced a 15% decline in late autumn and early winter rainfall and a 25% decline in average rainfall in April and May. Rainfall for January to August 2019 was the lowest on record in the Southern Downs (Queensland) and Northern Tablelands (New South Wales) with some areas 77% below the long term average.[40]

In the 2000s the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that ongoing anthropogenic climate change was virtually certain to increase in intensity and frequency of fires in Australia – a conclusion that has been endorsed in numerous reports since.[33] In November 2019, the Australian Climate Council published a report titled This is Not Normal[7] which also found the catastrophic bushfire conditions affecting NSW and Queensland in late 2019 have been aggravated by climate change.[40] According to Nerilie Abram writing in Scientific American "the link between the current extremes and anthropogenic climate change is scientifically indisputable".[33]

Carbon emissions

Until the 2019–2020 Australian bushfire season, the forests in Australia were thought to reabsorb all the carbon released in bushfires across the country. This would mean the forests achieved net-zero emissions. However, scientists now say that global warming is making bushfires burn more intensely and frequently and believe the current fires have already released about 350 million tonnes of carbon dioxide – as much as two-thirds of Australia's average annual carbon dioxide emissions (530 million tonnes in 2017)[41] in just the past three months. David Bowman, professor of pyrogeography and fire science at the University of Tasmania warns that so much damage has been done that Australian forests may take more than 100 years to re-absorb the carbon that has been released so far this fire season.[42]

These bushfire emissions increase Australia's contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating the problems associated with global warming. Climate studies show that conditions which promote extreme bushfires in Australia will only get worse as more greenhouse gases are added to the atmosphere.[38]

Seasonality

Bushfires in Australia can occur all year-round, though the severity and the "bushfire season" varies by region.[43] These seasons are commonly grouped into years such as "2019–2020 Australian bushfire season" and typically run from June one year until May the next year.

In southeast Australia, bushfires tend to be most common and most severe during summer and autumn (December–March), in drought years, and particularly severe in El Niño years. Southeast Australia is fire-prone, and warm and dry conditions intensify the probability of fire.[44] In northern Australia, bushfires usually occur during the dry season (April to September),[45] and fire severity tends to be more associated with seasonal weather patterns. In the southwest, similarly, bushfires occur in the summer dry season and severity is usually related to seasonal growth. Fire frequency in the north is difficult to assess, as the vast majority of fires are caused by human activity, however, lightning strikes are as common a cause as human-ignited fires and arson.

Impact on wildlife

Bush fires kill animals directly and also destroy local habitats, leaving the survivors vulnerable even once the fires have passed. Professor Chris Dickman at Sydney University estimates that in the first three months of the 2019–2020 bushfires, over 800 million animals died in NSW, and more than 1 billion nationally.[46] This figure includes mammals, birds, and reptiles but does not include insects, bats or frogs. Many of these animals were burnt to death in the fires, with many others dying later due to the depletion of food and shelter resources and predation by feral cats and red foxes. Dickman adds that Australia has the highest rate of species lost of any area in the world,[47] with fears that some of Australia's native species, like the Kangaroo Island dunnart, may even become extinct because of the current fires.[48]

Koalas are perhaps the most vulnerable because they are slow-moving. In extreme fires, koalas tend to climb up to the top of a tree and curl into a ball where they become trapped. In January 2020 it was reported that half of the 50,000 koalas on Kangaroo Island off Australia's southern coast, which are kept separate to those on the mainland as insurance for the species’ future, are thought to have died in the previous few weeks.[49]

Wildlife ecologist Professor Euan Ritchie from Deakin University says that when fires have passed, frogs and skinks are left vulnerable when their habitats have been destroyed. Loss of habitat also affects already endangered species such as the western ground parrot, the Leadbeater's possum, the Mallee emu-wren (a bird which cannot fly very far), and Gilbert's potoroo. Beekeepers have also lost hives in bushfires.[32]

Kangaroos and wallabies can move quickly trying to escape from fires. However, the Guardian reported in January 2020 that dozens, maybe hundreds of kangaroos "perished in their droves" as they tried to outrun the flames near Batlow in NSW.[49] The most resilient animals are those that can burrow or fly. Possums often get singed, but can sometimes hide in tree hollows. Wombats and snakes tend to go underground.[32]

Goannas can benefit from bushfires. Dickman says: "In central Australia, we've seen goannas coming out from their burrows after a fire and picking off injured animals – singed birds, young birds, small mammals, surface-dwelling lizards, and snakes."[32]

Impact on humans

The most devastating impact on humans is that bushfires have killed over 800 people since 1851.[50] In addition to loss of life, homes, properties, and livestock are destroyed potentially leaving people homeless, traumatised, and without access to electricity, telecommunications and, in some cases, to drinking water.[51]

Health

Bushfires produce particulate-matter pollution – airborne particles that are small enough to enter and damage human lung tissue. Following the Hazelwood fire in 2014, Fay Johnston, an associate professor of public health at the University of Tasmania's Menzies Institute for Medical Research, says young children exposed to smoke either as infants, toddlers or in the womb develop changes to their lung function. She says: "Unborn babies exposed to the Hazelwood smoke were more likely to experience coughs or colds two to four years after the fires."[52] Other studies conducted in Australia show an increase in respiratory diseases among adults stemming from air pollution caused by bushfires.[53]

As a result of intense smoke and air pollution stemming from the fires, in January 2020 Canberra measured the worst air quality index of any major city in the world. The orange-tinged smoke entered homes and offices buildings across the capital making breathing outside very difficult, forcing businesses and institutions to shut their doors.[54] Studies show that residents of highly polluted cities also have an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and diabetes. Professor Jalaluddin, a chief investigator with the Centre for Air Pollution, Energy and Health Policy Research, says: "There is increasing evidence around air pollution and (the development of) neurological conditions, for example, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's."[52]

Prof David Bowman, director of the Fire Centre Research Hub at the University of Tasmania, refers to the 2019–2020 fires as "absolutely transformative and unprecedented" in scale and says: "It's pretty much a third of the Australian population that has been impacted, with prolonged, episodic exposure and sometimes extreme health impacts." Since September 2019, close to 3,000 firefighters have been out every day in NSW battling blazes. The NSW RFS says close to 90% of those are unpaid volunteers.[55] David McBride, associate professor of occupational and environmental medicine at the University of Otago says: "They push themselves to the limit – they can suffer heat stress, which is a life-threatening injury, and end up with chronic bronchitis and asthma".[56]

Psychological problems

Psychological problems following a major bushfire appear to develop when people have a chance to stop and reflect on their experience. A study of 1,526 people who experienced significant losses in the 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires found that after 12 months, 42% met the criteria for a psychiatric problem which is double the prevalence in an unaffected community. After twenty months this figure had dropped to 23%.[57]

A typical example of how people are affected is described by the 2016 fire at Yarloop in Western Australia. It virtually destroyed the town (population 395) including 180 homes, historic timber workshops, factories, an old church, the old hospital, shops, the hotel, the fire station and a part of the school. Two people died. Damage to infrastructure included the Samson Brook Bridge, Salmon River Bridge and power infrastructure supplying thousands of homes in the area.[58]

Two years later, local people were still suffering from trauma distress from the fire. Apart from the economic losses suffered by those who lived there, the dislocation to their lives was so great that many in the community were doubtful that the town would be rebuilt.[59] The State Government subsequently spent $64 million rebuilding the town and the surrounding communities.[60]

Economic impact

Economic damage from 2009's Black Saturday fires, the costliest in Australia's history, reached an estimated $4.4 billion. Moody's Analytics says the cost of the 2019–2020 bushfires is likely to exceed even that figure and will cripple consumer confidence and harm industries such as farming and tourism.[61] Medical bills from the current fires and smoke haze are expected to reach hundreds of millions of dollars with one analysis suggesting disruptions caused by the fire and smoke haze could cost Sydney as much as A$50 million a day.[62] The Insurance Council of Australia estimates that claims for damage from the fires would be more than A$700 million, with claims expected to jump when more fire-hit areas become accessible. In January 2020, the ANZ gauge of consumer confidence fell last week to its lowest level in more than four years.[51]

In response to the current fires, the federal government announced that compensation would be paid to volunteer firefighters, military personnel would be deployed to assist, and an A$2 billion bush fire recovery fund would be established. New South Wales, which has been hardest hit by the crisis, has pledged A$1 billion focused on repairing infrastructure.[63]

Official inquiries

After many major bushfires, state and federal governments in Australia have initiated inquiries to see what could be done to address the problem. A parliamentary report from 2010 says that between 1939 and 2010, there have been at least 18 major bushfire inquiries including state and federal parliamentary committee inquiries, COAG reports, coronial inquiries and Royal Commissions.[64] Another report published in 2015 says there have been 51 inquiries into wildfires and wildfire management since 1939. The authors note that: "The fact that catastrophic events continue to recur is evidence either that the community is failing to learn the lessons from the past, or the inquiries fail to identify the true learning – that catastrophic events may be inevitable, or that Royal Commissions are not the most effective way to identify relevant lessons from past events".[65]

In January 2020, in the middle of the 2019–2020 bushfire season, Prime Minister Scott Morrison raised the prospect of establishing another royal commission. Morrison told Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that any inquiry into the crisis would need to be comprehensive and investigate climate change as well as other possible causes.[66]

Warnings

During the fire season, the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) provides fire weather forecasts. Fire agencies determine the appropriate Fire Danger Rating by considering the predicted weather including temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and dryness of vegetation. These Fire Danger Ratings are a feature of weather forecasts and alert the community to the actions they should take in preparation for the day. Ratings are broadcast via newspapers, radio, TV, and the internet.[67]

In 2009, a standardised Fire Danger Rating (FDR) was adopted by all Australian states. This included a whole new level – catastrophic fire danger. The first time this level of danger was forecast for Sydney was in November 2019 during the 2019–2020 Australian bushfire season.[68] In 2010, following a national review of the bush fire danger ratings, new trigger points for each rating were introduced for grassland areas in most jurisdictions.

| Category | Fire Danger Index |

|---|---|

| Catastrophic / Code Red | Forest 100+ Grass 150+ |

| Extreme | Forest 75–100 Grass 100–150 |

| Severe | Forest 50–75 Grass 50–100 |

| Very high | 25–50 |

| High | 12–25 |

| Low to moderate | 0–12 |

Remote monitoring

Remote monitoring of wildfires is done in Australia. Geoscience Australia developed the (real-time) Sentinel bushfire monitoring system. It uses data from satellites to help fire-fighting agencies assess and manage risks.[69][70][71] There is also MyFireWatch, which is a program based on an existing Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES) program, redeveloped by Landgate and Edith Cowan University (ECU) for use by the general public.[72][73] Besides the use of satellites, Australian firefighters also make use of UAV's as a tool for combating fire.[74]

Regional management

The Australasian Fire Authorities Council (AFAC) is the peak body responsible for representing fire, emergency services, and land management agencies in the Australasian region.

Queensland

The Rural Fire Service (RFS) is a volunteer-based firefighting agency and operates as part of the Queensland Fire and Emergency Services.[75]

New South Wales

Fire and Rescue NSW (FRNSW), the Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW), the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and the New South Wales Rural Fire Service (RFS) work together to manage and respond to fires across New South Wales.

South Australia

The Country Fire Service is a volunteer-based fire service in the state of South Australia. The CFS operates as a part of the South Australian Fire and Emergency Services Commission (SAFECOM).

Victoria

In Victoria, the Country Fire Authority (CFA) provides firefighting and other emergency services to country areas and regional townships within the state, as well as large portions of the outer suburban areas and growth corridors of Melbourne not covered by the Metropolitan Fire Brigade.[76]

Responsibility for fire suppression and management, including planned burning on public land such as State Forests and National Parks, which makes up about 7.1 million hectares or about one-third of the State, sits with the Department of Environment, Land, Water, and Planning (DELWP).

Western Australia

The Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES) and the Department of Parks and Wildlife (P&W) have joint responsibility for bushfire management in Western Australia.[77] DFES is an umbrella organisation supporting the Fire and Rescue Service (FRS), Bush Fire Service (BFS), Volunteer Fire and Rescue Service (VFRS), State Emergency Service (SES), Volunteer Fire and Emergency Service (VFES), Emergency Services Cadets and the Volunteer Marine Rescue Service (VMR).

Tasmania

The Tasmania Fire Service manages bushfires in Tasmania with the help of Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and Forestry Tasmania.[78][79]

Guidelines for survival

Local authorities provide education and information for residents in bushfire-prone regions regarding the location of current fires,[80] preservation of life and property[81] and when to escape by car.[82]

Major bushfires in Australia

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2020) |

This section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (January 2020) |

Bushfires have accounted for over 800 deaths in Australia since 1851 and, in 2012, the total accumulated cost was estimated at $1.6 billion.[83] In terms of monetary cost however, they rate behind the damage caused by drought, severe storms, hail, and cyclones,[84] perhaps because they most commonly occur outside highly populated urban areas. However, the severe fires of the summer of 2019–2020 affected densely populated areas including holiday destinations leading NSW Rural Fire Services Commissioner, Shane Fitzsimmons, to claim it was "absolutely" the worst bushfire season on record.[85]

Some of the most severe Australian bushfires (single fires and fire seasons), in chronological order, have included: (note the 1974/1975 and 2019/2020 bushfires have a combined total of hectares burned)

| Name or description | State(s) / territories |

Area burned (approx.) |

Date | Fatalities | Properties damaged | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ha | acres | ||||||

| Black Thursday bushfires | Victoria | 5,000,000 | 12,000,000 | 6 February 1851 | about 12 | 1 million sheep; thousands of cattle | [86][87] |

| Red Tuesday bushfires | Victoria | 260,000 | 640,000 | 1 February 1898 | 12 | 2,000 buildings | [87] |

| 1926 bushfires | Victoria | 390,000 | 960,000 | February–March 1926 | 60 | 1,000 | [88] |

| Black Friday bushfires | Victoria | 2,000,000 | 4,900,000 | December 1938 – January 1939 | 71 | 3,700 | |

| 1944 bushfires | Victoria | 1,000,000 | 2,500,000 | 14 January – 14 February 1944 | 15–20 | more than 500 houses | [87] |

| Woodford/Springwood Bushfire 1944, Blue Mountains | New South Wales | 18 November 1944 | Nil | 27 homes | |||

| 1951–52 bushfires | Victoria | 4,000,000 | 9,900,000 | November 1951 – January 1952 | 11 | [89] | |

| Black Sunday bushfires | South Australia | 39,000–160,000 | 96,000–395,000 | 2 January 1955 | 2 | 40 dwellings including the Governor's summer residence at Marble Hill | |

| Grose Valley bushfire, Blue Mountains 1957 | New South Wales | 30 November 1957 | 4 | 4 boys were killed on a bush walk out to Perrys Lookdown. 5 others survived. The leader of the group got help at Blackheath[citation needed] | |||

| 1957 Leura bushfire, Blue Mountains | New South Wales | 2 December 1957 | Nil | 170 homes in parts of Katoomba, Leura and Wentworth falls | One building that was destroyed was the Chateau Napier.[citation needed] | ||

| 1961 Western Australian bushfires | Western Australia | 1,800,000 | 4,400,000 | January–March 1961 | Nil | 160 homes | [90] |

| 1962 bushfires | Victoria | 14–16 January 1962 | 32 | 450 houses | [88] | ||

| 1965 Gippsland bushfires | Victoria | 315,000 | 780,000 | 21 Feb –

13 March 1965 |

Nil | 60 buildings, 4000 stock | [91] |

| Southern Highlands bushfires | New South Wales | 251,000 | 620,000 | 5–14 March 1965 | 3 | 59 homes | |

| Tasmanian "Black Tuesday" bushfires | Tasmania | 264,000 | 650,000 | 7 February 1967 | 62 | 1,293 homes | [87] |

| Dandenong Ranges bushfire | Victoria | 1,920 | 4,700 | 19 February 1968 | 53 homes; 10 other buildings | ||

| 1968-69 Killarney Top Springs bushfires | Northern Territory | 40,000,000 | 99,000,000 | 1968–69 | [92] | ||

| 1968 Blue Mountains Bushfire | New South Wales | 29 November 1968 | 4 | over 120 homes | |||

| 1969 bushfires | Victoria | 8 January 1969 | 23 | 230 houses | [88] | ||

| 1969-70 Dry River-Victoria River fire | Northern Territory | 45,000,000 | 110,000,000 | 1969–70 | [92] | ||

| 1974–75 Australian bushfire season[a] | Nationwide | 117,000,000 | 290,000,000 | 1974–1975 season | 3 | 15% of Australia burned up. The damage was mostly in central Australia and so it did not impact many communities.

"The 1974/75 fires had almost no impact and much of the damage was found by satellite after the fact”[95] |

[93][96][97] |

| 1974 Moolah-Corinya bushfires, Far West NSW | New South Wales | 1,117,000 | 2,760,000 | Mid-December 1974 | 3 | 40 homes, 10,170 kilometres (6,320 mi) of fencing, 50,000 livestock | [98][99][100][101] |

| 1974 Cobar bushfire | New South Wales | 1,500,000 | 3,700,000 | Mid-December 1974 | [98][99][100][101] | ||

| 1974 Balranald bushfire | New South Wales | 340,000 | 840,000 | Mid December 1974 | [99][100][101] | ||

| 1974–75 New South Wales bushfires | New South Wales | 4,500,000 | 11,000,000 | 1974–1975 season | 6 | [102][103][104] | |

| 1974–1975 Northern Territory bushfires | Northern Territory | 45,000,000 | 110,000,000 | 1974–1975 season | [92] | ||

| 1974–1975 Queensland bushfires | Queensland | 7,500,000 | 19,000,000 | 1974–1975 season | [92] | ||

| 1974–1975 South Australia bushfires | South Australia | 17,000,000 | 42,000,000 | 1974–1975 season | [92] | ||

| 1974–1975 Western Australia bushfires | Western Australia | 29,000,000 | 72,000,000 | 1974–1975 season | [92] | ||

| Western Districts bushfires | Victoria | 103,000 | 250,000 | 12 February 1977 | 4 | 116 houses, 340 buildings | |

| Blue Mountains Fires 1977 | New South Wales | 54,000 | 130,000 | 17 December 1977 | 2 | 49 houses | |

| 1978 Western Australian bushfires | Western Australia | 114,000 | 280,000 | 4 April 1978 | 2 | 6 buildings (drop in wind in early evening is said to have saved the towns of Donnybrook, Boyup Brook, Manjimup, and Bridgetown.) | |

| 1979 Sydney bushfires | New South Wales | December 1979 | 5 | 28 homes destroyed, 20 homes damaged | [105] | ||

| 1980 Waterfall bushfire | New South Wales | 1,000,000 | 2,500,000 | 3 November 1980 | 5 firefighters | 14 homes | [106] |

| Grays Point bushfire | New South Wales | 9 January 1983 | 3 volunteer firefighters | [107] | |||

| Ash Wednesday bushfires |

|

418,000 | 1,030,000 | 16 February 1983 | 75 | about 2,400 houses | |

| 1984 Western New South Wales grasslands bushfires | New South Wales | 500,000 | 1,200,000 | 25 December 1984 | 40,000 livestock, $40 million damage | [99][100][101] | |

| 1985 Cobar bushfire | New South Wales | 516,000 | 1,280,000 | Mid January 1985 | Nil | [99][100] | |

| 1984/85 New South Wales bushfires | New South Wales | 3,500,000 | 8,600,000 | 1984–1985 season | 5 | [99][100][101][102][103][104] | |

| Central Victoria bushfires | Victoria | 50,800 | 126,000 | 14 January 1985 | 3 | 180+ houses | |

| 1994 Eastern seaboard fires | New South Wales | 400,000 | 990,000 | 27 December 1993 –

16 January 1994 |

4 | 225 homes | [108] |

| Wooroloo bushfire | Western Australia | 10,500 | 26,000 | 8 January 1997 | Nil | 16 homes | |

| Dandenongs bushfire | Victoria | 400 | 990 | 21 January 1997 | 3 | 41 homes | [109] |

| Lithgow bushfire | New South Wales | 2 December 1997 | 2 firefighters | [109] | |||

| Menai bushfire | New South Wales | 2 December 1997 | 1 firefighter | 11 homes destroyed, 30 homes damaged | [110] | ||

| Perth and SW Region bushfires | Western Australia | 23,000 | 57,000 | 2 December 1997 | 2 | 1 home lost | |

| Linton bushfire | Victoria | 2 December 1998 | 5 firefighters | [111] | |||

| Black Christmas bushfires | New South Wales | 300,000 | 740,000 | 25 December 2001 – 2002 | Nil | 121 homes | |

| 2002 NT bushfires | Northern Territory | 38,000,000 | 94,000,000 | August–November 2002 | [92] | ||

| 2003 Canberra bushfires | Australian Capital Territory | 160,000 | 400,000 | 18–22 January 2003 | 4 | almost 500 homes | [109] |

| 2003 Eastern Victorian alpine bushfires | Victoria | 1,300,000 | 3,200,000 | 8 January – 8 March 2003 | 3 | 41 homes | |

| Tenterden | Western Australia | 2,110,000 | 5,200,000 | December 2003 | 2 | [citation needed] | |

| 2005 Eyre Peninsula bushfire | South Australia | 77,964 | 192,650 | 10–12 January 2005 | 9 | 93 homes | |

| 2006 Central Coast bushfire | New South Wales | New Years Day, 2006 | |||||

| Jail Break Inn Fire, Junee | New South Wales | 30,000 | 74,000 | New Years Day 2006 | Nil | Livestock losses estimated to be over 20,000. Seven homes, seven headers and four shearing sheds destroyed. 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) of fencing damaged. | [112][113] |

| 2005 Victorian bushfires | Victoria | 160,000 | 400,000 | December 2005 –

January 2006 |

4 | 57 houses, 359 farm buildings, 65,000 stock losses, fires occurred in the Stawell, Moondarra, Anakie, Yea, and Kinglake regions. | [114] |

| Grampians bushfire | Victoria | 184,000 | 450,000 | January 2006 | 2 | ||

| Pulletop bushfire, Wagga Wagga | New South Wales | 9,000 | 22,000 | 6 February 2006 | Nil | 2,500 sheep and 6 cattle killed, 3 vehicles and 2 hay sheds destroyed as well as 50 kilometres (31 mi) of fencing. | |

| The Great Divides bushfire | Victoria | 1,048,000 | 2,590,000 | 1 December 2006 –

March 2007 |

1 | 51 homes | |

| 2006–07 Australian bushfire season |

|

1,360,000 | 3,400,000 | September 2006 –

January 2007 |

5 | Over 100 structures including 83 houses; numerous non-residential structures | [115][116][117][118][119][120][121] |

| Dwellingup bushfire | Western Australia | 12,000 | 30,000 | 4 February 2007 | Nil | 16 | |

| Kangaroo Island bushfires | South Australia | 95,000 | 230,000 | 6–14 December 2007 | 1 | ||

| Boorabbin National Park | Western Australia | 40,000 | 99,000 | 30 December 2007 | 3 | Powerlines and Great Eastern Highway, forced to close for 2 weeks. | |

| Black Saturday bushfires | Victoria | 450,000 | 1,100,000 | 7 February 2009 –

14 March 2009 |

173 | 2,029+ houses, 2,000 other structures. | |

| Toodyay bushfire | Western Australia | 3,000 | 7,400 | 29 December 2009 | Nil | 38 | |

| Lake Clifton bushfire | Western Australia | 2,000 | 4,900 | 11 January 2011 | Nil | 10 homes destroyed. | |

| Roleystone Kelmscott bushfire | Western Australia | 1,500 | 3,700 | 6–8 February 2011 | Nil | 72 homes destroyed, 32 damaged, Buckingham Bridge on Brookton Highway collapsed and closed for 3 weeks whilst a temporary bridge was constructed and opened a month after the fires. | |

| Margaret River bushfire | Western Australia | 4,000 | 9,900 | 24 November 2011 | Nil | 34 homes destroyed including the historic Wallcliffe House. | [122] |

| Tasmanian bushfires | Tasmania | 20,000 | 49,000 | 4 January 2013 | 1 | At least 170 buildings | |

| Warrumbungle bushfire | New South Wales | 54,000 | 130,000 | 18 January 2013 | Nil | At least 53 homes, 118 sheds, agricultural machinery and livestock. Infrastructure destroyed at Siding Spring Observatory. | [123] |

| 2013 New South Wales bushfires | New South Wales | 100,000 | 250,000 | 17–28 October 2013 | 1 | As of 19 October 2013[update] at least 248 buildings destroyed statewide (inc. 208 dwellings), another 109 damaged in Springwood, Winmalee and Yellow Rock. Major fires also occurred in the Hunter, Central Coast, Macarthur and Port Stephens regions causing significant damage. | [124][125][126] |

| Carnarvon bushfire complex | Western Australia | 800,000 | 2,000,000 | 27 December 2011 –

3 February 2012 |

Nil | 11 pastoral stations (fences, watering systems, water points, stock feed). | |

| 2014 Parkerville bushfire | Western Australia | 386 | 950 | 12 January 2014 | Nil | 56 homes. | |

| 2015 Sampson Flat bushfires | South Australia | 20,000 | 49,000 | 2–9 January 2015 | Nil | 27 homes, 140 outbuildings | |

| 2015 O'Sullivan bushfire (Northcliffe – Windy Harbour) | Western Australia | 98,923 | 244,440 | 29 January – 20 February 2015 | Nil | 1 home and 1 inhabited shed, 5 farm sheds and thousands of hectares of production forests (karri and jarrah) or national parks. | |

| 2015 Lower Hotham bushfire (Boddington) | Western Australia | 52,373 | 129,420 | January 2015 | Nil | 1 house, 1 farm shed, 1 bridge and thousands of hectares of production forest (jarrah) or national parks. | |

| 2015 Esperance bushfires | Western Australia | 200,000 | 490,000 | October–November 2015 | 4 | About 10 houses and public buildings (Scaddan), 15,000 stock losses, 5 Nature Reserves et most area of Cape Arid national park. | [127][128] |

| Perth Hills bushfire complex – Solus Group | Western Australia | 10,016 | 24,750 | 15–24 November 2015 | Nil | Jarrah production forest and Conservation Park. | |

| 2015 Pinery bushfire | South Australia | 85,000 | 210,000 | 25 November – 2 December 2015 | 2 | 91 dwellings. | |

| 2016 Murray Road bushfire (Waroona and Harvey) | Western Australia | 69,165 | 170,910 | January 2016 | 2 | 181 dwellings (166 only in Yarloop), historical Yarloop Workshops and thousands of hectares of Lane Poole Reserve and production forest (jarrah). | [129] |

| 2017 New South Wales bushfires | New South Wales | 52,000 | 130,000 | 11–14 February 2017 | Nil | 35 dwellings. | [130] |

| 2017 Carwoola bushfire | New South Wales | 3,500 | 8,600 | 17–18 February 2017 | Nil | 11 dwellings destroyed; 12 damaged. | [131] |

| 2018 Tathra bushfire | New South Wales | 1,200 | 3,000 | 18–19 March 2018 | Nil | 69 houses and 30 caravans/cabins destroyed; 39 damaged. | [132] |

| Tabulam bushfire | New South Wales | 4,000 | 9,900 | early February 2019 | Nil | 10 homes and 23 outbuildings destroyed. | |

| Tingha bushfire | New South Wales | 17,000 | 42,000 | early February 2019 | Nil | 8 homes and 18 outbuildings destroyed. | |

| 2019–20 Australian bushfire season |

|

18,626,000 | 46,030,000 | 5 September 2019 – present | 29 (including 3 NSW firefighters and 1 VIC firefighter) | 2600+ homes currently confirmed destroyed (as of 13 January 2020)

|

Area[133] Other[134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145] At least 1,000,000,000 wild animals are estimated to have died (not including frogs and insects) with some species thought to be facing extinction.[146] |

See also

- Aerial firefighting and forestry in southern Australia

- Angry Summer, 2012–2013 Australian summer

- Early 2009 southeastern Australia heat wave, which generated extreme fire conditions

- List of natural disasters in Australia

- McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index

- AS3959

- Pyrotron, a device designed to help firefighters better understand how to combat the rapid spread of bush fires

- Wildfires in the United States

Notes

- ^

The 1974–75 bushfire season burnt over 100 Mha, but there are different figures reported:

- In 1995, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported 117 Mha[93]

- The 2004 National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management reports a total of 102 Mha[94]

References

- ^ John Vandenbeld; Nature of Australia - Episode Three: The Making of the Bush; ABC video; 1988

- ^ Tronson, mark. "Bushfires – across the nation". Christian. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ The worst bushfires in Australia’s history; 3 Nov 2011; Australian Geographic]

- ^ The worst bushfires in Australia’s history; 3 Nov 2011; Australian Geographic]

- ^ "'Extraordinary' 2019 ends with deadliest day of the worst fire season". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ Estimated 1.25 billion animals killed in Australian bushfires, TV10, 10 January 2020

- ^ a b This is Not Normal: Climate Change and Escalating bushfire risk, Climate Council, 12 November 2019

- ^ White, M. E. 1986. The Greening of Gondwana. Reed Books, Frenchs Forest, Australia.

- ^ Geofrrey Blainey The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia; Penguin Viking; 2015; p50-51

- ^ Geofrrey Blainey The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia; Penguin Viking; 2015; p 59

- ^ "The Fire Book". Tangentyre Landcare. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2015.

- ^ Flannery, Tim. The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People, Grove Press 2002

- ^ "Historical role of fire" Ward, D.J., Lamont, B.B. & Burrows, C.L. (2001) Grasstrees reveal contrasting fire regimes in eucalypt forest before and after European settlement of southwestern Australia. Forest Ecology and Management 150: 323–329.

- ^ Wilson, Nicholas; Cary, Geoffrey J.; Gibbons, Philip (15 June 2018). "Relationships between mature trees and fire fuel hazard in Australian forest". International Journal of Wildland Fire. 27 (5): 353–362. doi:10.1071/WF17112. hdl:1885/160659.

- ^ "Gamba grass (Andropogon gayanus)". A–Z listing of weeds: Photo guide to weeds. Queensland Department of Primary Industries.

- ^ Lesley Head, Jennifer Atchison. 2015. Governing invasive plants: Policy and practice in managing the Gamba grass (Andropogon gayanus) – Bushfire nexus in northern Australia. Land Use Policy 47: 225–234

- ^ Geofrrey Blainey The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia; Penguin Viking; 2015; pp. 386-387

- ^ Forest Fire Management Victoria - Past bushfires; www.ffm.vic.gov.au; online 19 Jan 2020

- ^ Geofrrey Blainey The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia; Penguin Viking; 2015; p.387

- ^ Forest Fire Management Victoria - Past bushfires; www.ffm.vic.gov.au; online 19 Jan 2020

- ^ a b "Black Friday 1939". Forest Fire Management Victoria. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Lessons learnt (and perhaps forgotten) from Australia's 'worst fires'; smh.com.au; 11 Jan 2019

- ^ Bush Fires Over Wide Area]; The Argus; 16 Jan 1939

- ^ Right fire for right future: how cultural burning can protect Australia from catastrophic blazes, The Guardian, 18 January 2020

- ^ Reducing fire, and cutting carbon emissions, the Aboriginal way, NZ Herald, 17 January, 2020

- ^ Right fire for right future: how cultural burning can protect Australia from catastrophic blazes, The Guardian, 18 January 2020

- ^ "We crunched the numbers on bushfires and arson — the results might surprise you". 10 January 2020.

- ^ "Some Coalition MPS say arson is mostly to blame for the bushfire crisis. Here are the facts". 14 January 2020.

- ^ How Wildfires Work, Kevin Bonsor, How Stuff Works

- ^ Newey, Sarah (2 January 2020). "Australia is burning – but why are the bushfires so bad and is climate change to blame?". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Fire Behaviour". The Bushfire Foundation.

- ^ a b c d Australia bushfires: Which animals typically fare best and worst? BBC, 22 November 2019

- ^ a b c Nerilie Abram (31 December 2019). "Australia's Angry Summer: This Is What Climate Change Looks Like". Scientific American. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Australia bushfires spew two-thirds of national carbon emissions in one season, Stuff, 3 January 2019

- ^ Recent Australian droughts may be the worst in 800 years, The Conversation, 2 May 2018.

- ^ The facts about bushfires and climate change, Climate Council, 13 November 2019

- ^ Climate of the Nation2019, The Australia Institute, p. 3.

- ^ a b Explainer: what are the underlying causes of Australia's shocking bushfire season? The Guardian, 12 January 2020

- ^ "Bushfire weather in Southeast Australia: Media Brief", The Climate Institute, 26 September 2007. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ a b The Facts about Bushfires and Climate Change, Climate Council 13 November 2019

- ^ National Inventory by Economic Sector 2017, Australia’s National Greenhouse Accounts, Department of the Environment & Energy, August 2019, p. 3

- ^ Australia bushfires spew two-thirds of national carbon emissions in one season, Stuff, 3 January 2020

- ^ Luke RH, McArthur AG (1978). Bushfires in Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

- ^ Sullivan, Rohan (11 February 2009). "Hot and dry Australia sees wildfire danger rise". The Association Press. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Monsoonal Climate". Questacon. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- ^ "More than one billion animals killed in Australian bushfires". University of Sydney. 8 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ A statement about the 480 million animals killed in NSW bushfires since September, University of Sydney 3 January 2020

- ^ Kiwi volunteers helping fire-affected Australian animals, RNZ 12 January 2020

- ^ a b The world loves kangaroos and koalas. Now we are watching them die in droves, The Guardian, 6 January 2020

- ^ Tronson, mark. "Bushfires – across the nation". Christian Today. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ a b Australia strengthens bushfire defenses as economic, environmental costs mount, Reuters, 7 January 2020

- ^ a b Health impacts of bushfires won't be known for years, experts say, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 January 2020

- ^ Australia's bushfires mean New Zealand has become the land of the long pink cloud, the Guardian, 7 January 2020.

- ^ Canberra shuts down as smoke smothers city, The Canberra Times 5 January 2020.

- ^ Australia fires: The thousands of volunteers fighting the flames, BBC, 24 December 2019

- ^ Australia bushfires: Concern over long-term effects on firefighters' health, NewsHub 10 January 2020

- ^ Bushfires: are we doing enough to reduce the human impact? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Vol 59, Issue 4, April 2002

- ^ WA fires: deadly Waroona blaze contained but not controlled, downgraded to 'advice', WA Today. 9 January 2016.

- ^ Impacts of Bushfires, Bushfire Front

- ^ Rising from the ashes, Yarloop bounces back after devastating bushfires in 2016, ABC News 22 November 2019

- ^ Economic impact of Australia's bushfires set to exceed $4.4bn cost of Black Saturday, The Guardian, 8 January 2020.

- ^ Australia fires: The huge economic cost of Australia's bushfires, BBC, 20 December 2019

- ^ Australian Economy Struck by Wildfires, Setting Up Stimulus, Bloomberg. 9 January 2020

- ^ Chapter 2 – Previous bushfire inquiries, Parliament of Australia.

- ^ Bushfire and Natural Hazards, Learning from Adversity, Report no 2015.019, p.4.

- ^ PM flags "comprehensive" inquiry into Australian bushfires, Asia&Pacific News, 10 January 2020

- ^ "New Warning System Explained". Country Fire Authority. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ Catastrophic fire danger: what does it mean and what should we do in these conditions? The Guardian, 11 November 2019

- ^ "Real-time bushfire monitoring satellite system to be developed in Australia". ABC News. 11 August 2015.

- ^ "Bushfire tracking with Sentinel Hotspots". www.csiro.au.

- ^ "Sentinel Hotspots". sentinel.ga.gov.au.

- ^ Harradine, Natasha (28 September 2014). "Better bushfire information for regional communities". ABC News.

- ^ "MyFireWatch – Bushfire map information Australia". myfirewatch.landgate.wa.gov.au.

- ^ "Drones to assist firefighters in emergencies". NSW Government.

- ^ "Rural Fire Service Queensland".

- ^ "Country Fire Authority". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to DFES". Department of Fire and Emergency Services of Western Australia. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "About TFS". Tasmania Fire Service. 2019.

- ^ 2013 Tasmanian Bushfires Inquiry: Volume 1 (PDF) (Report). ISBN 978-0-9923581-0-5.

- ^ "NSW Current Fires". NSW Rural Fire Service.

- ^ "How to survive a bushfire" (PDF). NSW Rural Fire Service. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ "Driving in a bushfire". 13 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ "Summary of Major Bush Fires in Australia Since 1851". Romsey Australia. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "EMA Disasters Database". Emergency management Australia. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ Harriet Alexander; Laura Chung; Natassia Chrysanthos; Janek Drevikovsky; James Brickwood (1 January 2020). "'Extraordinary' 2019 ends with deadliest day of the worst fire season". The Sydney Morning Herald.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Black Thursday Archived 13 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d ABS 1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2004. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 March 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "Major bushfires in Victoria". Department of Sustainability and Environment. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "Chisholm, Alec H.". The Australian Encyclopaedia. Vol. 2. Sydney: Halstead Press. 1963. p. 207. Bushfires.

- ^ Matthews, H (2011) Karridale Bush Fires 1961, Karridale Progress Association Inc. ISBN 978-0-9871467-0-0

- ^ Victoria, Forest Fire Management (10 January 2019). "Past bushfires". Forest Fire Management Victoria. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ellis, Stuart; Peter Kanowski; R. J. Whelan (31 March 2004). "National inquiry on bushfire mitigation and management". University of Wollongong. p. 339. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

Table D.1

- ^ a b N. P. Cheney (1 January 1995). "BUSHFIRES – AN INTEGRAL PART OF AUSTRALIA'S ENVIRONMENT". 1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 1995. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ S. Ellis; P. Kanowski; R. J. Whelan (31 March 2004). "National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management, Council of Australian Governments". Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ a b Charis Chang (8 January 2020). "How the 2019 Australian bushfire season compares to other fire disasters". NEWS.COM.AU. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ https://www.news.com.au/technology/environment/how-the-2019-australian-bushfire-season-compares-to-other-fire-disasters/news-story/7924ce9c58b5d2f435d0ed73ffe34174

- ^ "In 1974–75, lush growth of grasses and forbs following exceptionally heavy rainfall in the previous two years provided continuous fuels through much of central Australia and in this season fires burnt over 117 million hectares or 15 per cent of the total land area of this continent." https://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/6C98BB75496A5AD1CA2569DE00267E48

- ^ a b "The Sydney Morning Herald from Sydney, New South Wales". Newspapers.com. 21 December 1974. p. 1. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Mac Dougall, I D (2003). "A National User-Driven approach towards a coordinated Fire Research Program" (PDF). The Australian Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bush Fires / Wild Fires – Australian Bushfire History". australiasevereweather.com. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Our Service's story" (PDF). NSW RFS Bush Fire Bulletin Souvenir Liftout 2010 Part Two. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ a b Ellis, Kanowski & Whelan (2004). COAG National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia. p. 341.

- ^ a b 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission Final Report (PDF). Parliament of Victoria. 2010. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-9807408-1-3.

- ^ a b "Bushfires in NSW: timelines and key sources" (PDF). NSW Parliament Issues Backgrounder Number 6. NSW Parliamentary Research Service. June 2014.

- ^ "Bushfire – Sydney and Region:1 December 1979". Attorney-General's Department (Australia). Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "1979 – 1980, Sydney and Region bushfire". Ministry for Police and Emergency Services. 18 September 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Mutton, Sheree (9 January 2014). "Shire fire horror still lingers 20 years on". St George & Sutherland Shire Leader. Fairfax Regional Media. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Bushfires – Get the Facts Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Attorney-General's Department. Retrieved 9 January 2013

- ^ a b c Northern Daily Leader, "Some past bushfires in Australia", p. 3, 10 February 2009

- ^ "Australian firefighters on alert for new flare-ups". edition.cnn.com. 4 December 1997. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Johnstone, Graeme (State Coroner); Gyorffy, Tom; Livermore, Garry (11 January 2002). "Report of the Investigation and Inquests into a Wildfire and the Deaths of Five Firefighters at Linton on 2 December 1998" (PDF). State Coroner's Office, Victoria. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "Bushfire threat eases in NSW". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 January 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ "Generous support coming in for farmers affected by bushfires". NSW Department of Primary Industries. New South Wales Government. 6 January 2006. Archived from the original on 18 September 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ http://home.iprimus.com.au/foo7/firesum.html

- ^ Kennedy, Les; David Braithwaite; Edmund Tadros (22 November 2006). "Man dies as early bushfire season grips NSW". The Age. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Report on the Tasmanian East Coast Fires: Community Recovery" (PDF). bodc.tas.gov.au. Australian Red Cross. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Authorities investigate forestry worker's death". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 January 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Morton, Adam; Orietta Guerrera; Bridie Smith (15 December 2006). "Bushfires claim first life". The Age. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Switzer, Renee (18 January 2007). "One dead in SA bushfire". The Age. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Body found in fire wreckage". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 18 January 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ "Woman fleeing bushfire burnt to death". Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Rain could help damp down WA bushfires". ABC News. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Van de Wetering, Jodie (11 March 2013). "A timeline of the Coonabarabran bushfires". ABC (Western Plains). Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Damage assessment and fire investigation" (PDF) (Press release). New South Wales Rural Fire Service. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Watch and Act – Linksview Road Fire, Springwood (Blue Mountains) 19/10/13 11:40". NSW Rural Fire Service. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Madden, James. "Firestorm destroys NSW communities as hundreds of homes could be lost". The Australian. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "Bushfire warning downgraded for Esperance – possible threat to lives and homes". 21 November 2015.

- ^ Taylor, Roxanne; Powell, Graeme (18 November 2015). "German backpackers, farmer believed dead in Esperance fires". ABC News. ABC. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Fergusson, Euan: Report of the Special Inquiry into the January 2016 Waroona Fire ("Reframing Rural Fire Management"), Government of Western Australia, Volume 1: Report, 29 April 2016.

- ^ "35 homes razed in NSW blazes: RFS". SBS News. SBS. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Le Lievre, Kimberley; Groch, Sherryn; Brown, Andrew (18 February 2017). "Police investigate blaze near Queanbeyan as fire crews battle on". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Bushfire in Tathra wipes out 69 homes, residents still unable to return to NSW south coast town". ABC. 19 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Freya Noble (14 January 2020). "Government set to revise total number of hectares destroyed during bushfire season to 17 million". 9NEWS. Nine Digital. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Update on Northern NSW bush fires". NSW Rural Fire Service. 11 October 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Property losses from recent NSW bush fires" (PDF). NSW Rural Fire Service. 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Initial Assessment of Fire Affected Areas". rfs.nsw.gov.au. 9 September 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "NSW Police Public Site". police.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Update on NSW bush fire property losses". www.rfs.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "'There's nowhere to go': Fireys fear". news.com.au. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "More than 200 homes burn down in latest bushfires". 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Victoria's bushfires by the numbers". 4 January 2020.

- ^ "Smoke from NSW bushfires blankets Melbourne as city swelters". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Crews battle to control fire ahead of more extreme heat". The Advertiser. 24 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Community Update for the Ravine Fire". South Australian Country Fire Service. 5 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Victoria Fires: firefighter dies battling Omeo bushfire". Sydney Morning Herald. 11 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Brulliard, Karin; Fears, Darryl. "A billion animals have been caught in Australia's fires. Some may go extinct". Washington Post.