Phobos (moon)

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Asaph Hall |

| Discovery date | August 18, 1877 |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Epoch J2000 | |

| Periapsis | 9235.6 km |

| Apoapsis | 9518.8 km |

| 9377.2 km [2] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0151 |

| 0.318 910 23 d (7 h 39.2 min) | |

Average orbital speed | 2.138 km/s |

| Inclination | 1.093° (to Mars' equator) 0.046° (to local Laplace plane) 26.04° (to the ecliptic) |

| Satellite of | Mars |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 26.8 × 21 × 18.4 |

| 11.1 km (0.0021 Earths) | |

| ~6,100 km² (11.9 µEarths) | |

| Volume | ~5,500 km³ (5.0 nEarths) |

| Mass | 1.07×1016 kg (1.8 nEarths) |

Mean density | 1.9 g/cm³ |

| 0.0084-0.0019 m/s² (8.4-1.9 mm/s²) (860-190 µg) | |

| 0.011 km/s (11 m/s) | |

| synchronous | |

Equatorial rotation velocity | 11.0 km/h (at longest axis' tips) |

| 0° | |

| Albedo | 0.07 |

| Temperature | ~233 K |

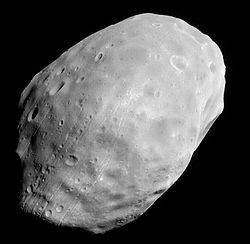

Phobos (IPA: [ˈfoʊ.bɑs] or IPA: [ˈfoʊ.bəs], Greek Φόβος: "Fright"), is the larger and innermost of Mars' two moons (the other being Deimos), and is named after Phobos, son of Ares (Mars) from Greek mythology. Phobos orbits closer to a major planet than any other moon in the solar system, less than 6000 km (3728 miles) above the surface of Mars, and is also one of the smaller known moons in the solar system. Its systematic designation is Mars I.

Discovery

Phobos was discovered by American astronomer Asaph Hall on August 18, 1877, at the US Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., at about 09:14 GMT (contemporary sources, using the pre-1925 astronomical convention that began the day at noon, give the time of discovery as August 17 16:06 Washington mean time).[1][2] Asaph Hall also discovered Deimos, Mars' other moon. At the time, he was deliberately searching for Martain moons. Hall had previously seen what appeared to be a Martian moon on August 10. Due to bad weather, he did not definitively identify them until later.[3]

The notebook of the discovery of Phobos by Asaph Hall is as follows:[4]

- I repeated the examination in the early part of the night of [August] 11th, and again found nothing, but trying again some hours later I found a faint object on the following side and a little north of the planet. I had barely time to secure an observation of its position when fog from the River stopped the work. This was at half past two o'clock on the night of the 11th. Cloudy weather intervened for several days.

- On 15 August the weather looking more promising, I slept at the Observatory. The sky cleared off with a thunderstorm at 11 o'clock and the search was resumed. The atmosphere however was in a very bad condition and Mars was so blazing and unsteady that nothing could be seen of the object, which we now know was at that time so near the planet as to be invisible.

- On August 16 the object was found again on the following side of the planet, and the observations of that night showed that it was moving with the planet, and if a satellite, was near one of its elongations. Until this time I had said nothing to anyone at the Observatory of my search for a satellite of Mars, but on leaving the observatory after these observations of the 16th, at about three o'clock in the morning, I told my assistant, George Anderson, to whom I had shown the object, that I thought I had discovered a satellite of Mars. I told him also to keep quiet as I did not wish anything said until the matter was beyond doubt. He said nothing, but the thing was too good to keep and I let it out myself. On 17 August between one and two o'clock, while I was reducing my observations, Professor Newcomb came into my room to eat his lunch and I showed him my measures of the faint object near Mars which proved that it was moving with the planet.

- On August 17 while waiting and watching for the outer moon, the inner one was discovered. The observations of the 17th and 18th put beyond doubt the character of these objects and the discovery was publicly announced by Admiral Rodgers.

— Asaph Hall

The names were suggested by Henry Madan (1838–1901), Science Master of Eton, from Book XV of the Iliad, where Ares summons Fear and Fright.[5]

Jonathan Swift's 'prediction'

In part 3 chapter 3 (the "Voyage to Laputa") of Jonathan Swift's famous satire Gulliver's Travels, a fictional work written in 1726, the astronomers of Laputa are described as having discovered two satellites of Mars orbiting at distances of 3 and 5 Martian diameters, and periods of 10 and 21.5 hours, respectively. The actual orbital distances and periods of Phobos and Deimos are 1.4 and 3.5 Martian diameters, and 7.6 and 30.3 hours, respectively. This is regarded as a fascinating coincidence; no telescope in Swift's day would have been even remotely powerful enough to discover these satellites.[6]

Orbital characteristics

This article possibly contains original research. |

Phobos orbits Mars below the synchronous orbit radius, meaning that it moves around Mars faster than Mars itself rotates. Therefore it rises in the west, moves comparatively rapidly across the sky (in 4 h 15 min or less) and sets in the east, approximately twice a day (every 11 h 6 min). It is so close to the surface (in a low-inclination equatorial orbit) that it cannot be seen above the horizon from latitudes greater than 70.4°.

As seen from Phobos, Mars would be 6400 times larger and 2500 times brighter than the full Moon as seen from Earth, taking up a ¼ of the width of a celestial hemisphere. As seen from Mars' equator, Phobos would be one-third the angular diameter of the full Moon as seen from Earth. Observers at higher Martian latitudes (less than the 70.4° latitude of invisibility) would see a smaller angular diameter because they would be farther away from Phobos. Phobos' apparent size would actually vary by up to 45% as it passed overhead, due to its proximity to Mars' surface. For an equatorial observer, for example, Phobos would be about 0.14° upon rising and swell to 0.20° by the time it reaches the zenith. By comparison, the Sun would have an apparent size of about 0.35° in the Martian sky.

Phobos' phases, in as much as they could be observed from Mars, take 0.3191 days to run their course (Phobos' synodic period), a mere 13 seconds longer than Phobos' sidereal period.

Death of a moon

Phobos' low orbit means that Phobos will eventually be destroyed: tidal forces are lowering its orbit, currently at the rate of about 1.8 metres per century, and in 30-80 million years it will either impact the surface of Mars or (more likely) break up into a planetary ring. Given Phobos' irregular shape and modeling it as a pile of rubble (specifically a Mohr-Coulomb body), it has been calculated that Phobos is stable with respect to tidal forces, but it is estimated that Phobos will pass the Roche Limit for a rubble pile when its orbital radius drops to about 7100 km, and will probably break up soon afterwards.[7]

Physical characteristics

Phobos is a dark body that appears to be composed of carbonaceous surface materials.[8] It is similar to the C-type asteroids.[9] Phobos' density is too low to be pure rock, however, and it is known to have significant porosity.[10][11][12] These results led to the suggestion that Phobos might contain a substantial reservoir of ice, but spectral observations have ruled out this hypothesis.[13]

The Soviet spacecraft Phobos 2 reported a faint but steady release of dust particles from Phobos.[14] Phobos 2 failed before it could determine the nature of the material.[15] Recent images from Mars Global Surveyor indicate that Phobos is covered with a layer of fine-grained regolith at least 100 meters thick.[16]

Phobos is highly nonspherical, with dimensions of 27 × 21.6 × 18.8 km. Because of its shape alone, the gravity on its surface varies by about 210%; the tidal forces raised by Mars more than double this variation (to about 450%) because they compensate for a little more than half of Phobos' gravity at its sub- and anti-Mars poles.

Phobos is heavily cratered.[17] The most prominent surface feature is the Stickney crater, named after Asaph Hall's wife's maiden name, Chloe Angeline Stickney Hall. Like Mimas's crater Herschel on a smaller scale, the impact that created Stickney must have almost shattered Phobos.[18] Many grooves and streaks also cover the oddly shaped surface. The grooves are typically less than 30 m deep, 100 to 200 m wide, and up to 20 km in length, and were originally assumed to have been the result of the same impact that created Stickney. Analysis of results from the Mars Express spacecraft, however, revealed that the grooves are in fact independent of Stickney, and are deposits of material thrown into space by impacts on the Martian surface.[19]

The unique Kaidun meteorite is claimed to be a piece of Phobos, but this has been difficult to verify since little is known about the detailed composition of the moon.[20]

Origin

Phobos and Deimos both have much in common with carbonaceous (C-type) asteroids, with very similar spectra, albedo and density to those seen in C-type asteroids.[9] This has led to speculation that both moons could have been captured into Martian orbit from the main asteroid belt.[21] However, both moons have very circular orbits which lie almost exactly in Mars' equatorial plane. Captured moons would be expected to have eccentric orbits in random inclinations. Some evidence suggests that Mars was once surrounded by many Phobos- and Deimos-sized bodies, perhaps ejected into orbit around it by a collision with a large planetesimal [22].

"Hollow Phobos" claims

Around 1958, Russian astrophysicist Iosif Samuilovich Shklovsky, studying the secular acceleration of Phobos' orbital motion, suggested a "thin sheet metal" structure for Phobos, a suggestion which led to speculations that Phobos was of artificial origin. Shklovsky based his analysis on estimates of the upper Martian atmosphere's density, and deduced that for the weak braking effect to be able to account for the secular acceleration, Phobos had to be very light —one calculation yielded a hollow iron sphere 16 km across but less than 6 cm thick.[23]

In a February 1960 letter to the journal Astronautics,[24] however, Siegfried Frederick Singer, then science advisor to President Eisenhower, came out in support of Shklovsky's theory, going as far as stating that "[Phobos'] purpose would probably be to sweep up radiation in Mars' atmosphere, so that Martians could safely operate around their planet". A few years later, in 1963, Raymond H. Wilson Jr., Chief of Applied Mathematics at NASA, allegedly announced to the Institute of Aerospace Sciences that "Phobos might be a colossal base orbiting Mars", and that NASA itself was considering the possibility.

While various theories attempted to explain the secular acceleration of Phobos, the existence of the acceleration was later subjected to doubt,[25] and the problem was solved by 1969.[26]

These claims had been made using an overestimated value of 5 cm/yr for the rate of altitude loss, which has been revised to 1.8 cm/yr. Tidal effects had not been considered, but are now believed to explain the secular acceleration. The density of Phobos is now measured to be 1.9 g/cm³, which is inconsistent with a hollow shell.

Similar "hollow Moon" and "hollow Earth" claims have been made.

Exploration missions

Past missions

Phobos has been photographed close-up by several spacecraft whose primary mission has been to photograph Mars. The first was Mariner 9 in 1971, Viking 1 in 1977, Mars Global Surveyor in 1998 and 2003, and by Mars Express in 2004. The Phobos 1 probe was lost en route to Mars, while its sister spacecraft, Phobos 2 was lost prior to beginning detailed examination of the satellite although some data had been returned from earlier parts of the mission.

Future missions

The Russian Space Agency is planning on launching a joint sample return mission with China in 2009, called Phobos-Grunt.

Astrium in the UK is planning a sample return mission.[27]

References

- Asaph Hall and the Moons of Mars

- I. S. Shklovsky, The Universe, Life, and Mind, Acad. of Sc. USSR, Moscow, 1962

Notes

- ^ "The Satellites of Mars". The Observatory, vol. 1. August 1877. p. 181. Retrieved September 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Hall, A (September 21, 1877). "Inner Satellite of Mars". Astronomische Nachrichten, volume 91. p. 11. Retrieved September 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Exploration Of Mars".

1877 was also significant in that it was the year of the discovery of the two Martian moons, Phobos and Deimos. They were discovered by an American astronomer, Asaph Hall, who was performing observations with a 66 centimeter refracting telescope in Washington DC. He was deliberately looking for Martian moons, and caught a glimpse of what might be a moon on 10 August. Any Martian moon had to be tiny to have missed being spotted by that time, and certainly Hall's expectations might have led him to grasp at straws, but he was a careful and methodical observer. Poor weather hindered his observations for the next few nights, but on 16 August, Hall not only spotted his moon again, but the next night also found a second moon.

- ^ "The Discovery of the Satellites of Mars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 38. February 1878. pp. 205–209. Retrieved September 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Names of the Satellites of Mars". Astronomische Nachrichten, vol. 92. February 7, 1878. pp. 47–48. Retrieved September 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Galileo's Anagrams and the Moons of Mars.

- ^ Holsapple K.A. (2001), Equilibrium Configurations of Solid Cohesionless Bodies, Icarus, v. 154, p. 432–448 [1]

- ^ Lewis, John S. (2004). Physics and Chemistry of the Solar System. Elsevier Academic Press. pp. pp.425. ISBN 0-12-446744-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Deimos".

- ^ "Porosity of Small Bodies and a Reassesment of Ida's Density".

When the error bars are taken into account, only one of these, Phobos, has a porosity below 0.2...

- ^ "Close Inspection for Phobos".

It is light, with a density less than twice that of water, and orbits just 5989 km above the Martian surface.

- ^ Busch, M.W. et al., 2007, Arecibo radar observations of Phobos and Deimos, Icarus 196, 581-584

- ^ Rivkin, A.S (2002). "Near-Infrared Spectrophotometry of Phobos and Deimos". Icarus. 156 (1): 64.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "A deep search for Martian dust rings and inner moons using the Hubble Space Telescope" (PDF).

- ^ "Phobos 1 and 2 to Mars".

- ^ "Forgotten Moons: Phobos and Deimos Eat Mars' Dust".

Like Mars' other moon, Deimos, Phobos has a thick layer of regolith, or dust and rock. It is thought to be especially thick on Phobos -- up to 330 feet (100 meters). Researchers think the regolith was created when other space rocks slammed into the moon, pounding it into powder. But scientists are stumped as to how the material stuck to an object that has almost no gravity.

- ^ "Phobos".

Unlike Deimos, Phobos's surface is battered and scarred.

- ^ "Stickney Crater-Phobos".

One of the most striking features of Phobos, aside from its irregular shape, is its giant crater Stickney. Because Phobos is only 28 by 20 kilometers (17 by 12 miles), the moon must have been nearly shattered from the force of the impact that caused the giant crater. Grooves that extend across the surface from Stickney appear to be surface fractures caused by the impact.

- ^ "Murray, J.B. et al, 37th ALPS conference, March 2006" (PDF).

- ^ "THE KAIDUN METEORITE: WHERE DID IT COME FROM?" (PDF).

The currently available data on the lithologic composition of the Kaidun meteorite– primarily the composition of the main portion of the meteorite, corresponding to CR2 carbonaceous chondrites and the presence of clasts of deeply differentiated rock – provide weighty support for considering the meteorite's parent body to be a carbonaceous chondrite satellite of a large differentiated planet. The only possible candidates in the modern solar system are Phobos and Deimos, the moons of Mars.

- ^ "Close Inspection for Phobos".

One idea is that Phobos and Deimos, Mars's other moon, are captured asteroids.

- ^ Craddock R.A. (1994), The Origin of Phobos and Deimos, Abstracts of the 25th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, held in Houston, TX, 14-18 March 1994., p.293

- ^ E. J. Öpik (September 1964). "Is Phobos artificial?". Irish Astronomical Journal, Vol. 6. pp. 281–283. Retrieved September 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ S. F. Singer, Astronautics, February 1960

- ^ "Phobos, Nature of Acceleration". Irish Astronomical Journal, Vol. 6. March 1963. p. 40. Retrieved September 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ S. F. Singer (1967). "On the origin of the Martian satellites Phobos and Deimos (Abstract only)". Seventh International Space Science Symposium held 10-18 May 1966 in Vienna, North-Holland Publishing Company.

- ^ BBC News- Jonathan Amos Martian moon 'could be key test'

See also

- Deimos, the other moon of Mars

- List of features on Phobos and Deimos

- Transit of Phobos from Mars

- Shadow of Phobos on Mars

- Phobos and Deimos in fiction

- Chinese space program