January–March 2014 North American cold wave

Temperature anomalies within the United States from January to March 2014, showcasing the very cold conditions | |

| Formed | January 2, 2014[1] |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | April 10, 2014 |

| Fatalities | 21 as of January 8[3][4] |

| Damage | $5 billion (United States)[2] |

| Areas affected | Canada, Central United States, Eastern United States, Northern Mexico |

Part of the 2013–14 North American winter | |

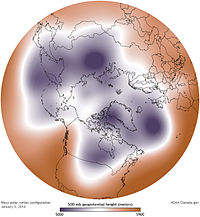

The early 2014 North American cold wave was an extreme weather event that extended through the late winter months of the 2013–2014 winter season, and was also part of an unusually cold winter affecting parts of Canada and parts of the north-central and northeastern United States.[5] The event occurred in early 2014 and was caused by a southward shift of the North Polar Vortex. Record-low temperatures also extended well into March.

On January 2, an Arctic cold front initially associated with a nor'easter tracked across Canada and the United States, resulting in heavy snowfall in some areas. Temperatures fell to unprecedented levels, and low temperature records were broken across the some areas of the United States. Business, school, and road closures were common, as well as mass flight cancellations across some airports in the Midwest.[6][7][8] Altogether, more than 200 million people were affected, in an area ranging from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean and extending south to include roughly 187 million residents of the Continental United States.[9]

Origins

Beginning on January 2, 2014, sudden stratospheric warming (SSW)[dubious – discuss] led to the breakdown of the semi-permanent feature across the Arctic known as the polar vortex. Without an active upper-level vortex to keep frigid air bottled up across the Arctic, the cold air mass was forced southward as upper-level warming displaced the jet stream. With extensive snow-cover across Canada and Siberia, Arctic air had no trouble remaining extremely cold as it was forced southward into the United States.[10]

According to the UK Met Office, the jet stream deviated[clarification needed] to the south (bringing cold air with it) as a result of unusual contrast between cold air in Canada and mild winter temperatures in the United States.[11][further explanation needed] This produced significant wind where the air masses met, leading to bitter wind chills and worsening the impacts of the record cold temperatures.[11][clarification needed]

Record temperatures

United States

On January 5, 2014, Green Bay, Wisconsin was −18 °F (−28 °C). The previous record low for this day was set in 1979.[12]

On January 6, 2014, Babbitt, Minnesota was the coldest place in the country at −37 °F (−38 °C).[13]

The low temperature at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago was −16 °F (−27 °C) on January 6. The previous record low for this day was −14 °F (−26 °C), set in 1884 and tied in 1988.[8][14] The National Weather Service adopted the Twitter hashtag #Chiberia (a portmanteau of Chicago and Siberia) for the cold wave coverage in Chicago[15] and local media adopted the term as well.[16][17] In spite of cold temperatures and stiff winds which exceeded the 29 miles per hour (47 km/h) and −23 °F (−31 °C) air temperature when Chicago set its all-time wind chill record of −82 °F (−63 °C) in 1983, Chicago did not break the record because the NWS had adopted a new wind chill formula in 2001.[18]

The average daily temperature for the United States on January 6 was calculated to be 17.9 °F (−7.8 °C). The last time the average for the country was below 18.00 °F (−7.78 °C) was January 13, 1997; the 17-year gap was the longest on record.[19]

On January 7, at least 49 record lows for the day were set across the country.[20] On the night of January 6–7, Detroit hit a low temperature of −14 °F (−26 °C) breaking the records for both dates. The high temperature of −1 °F (−18 °C) on January 7 was only the sixth day in 140 years of records to have a subzero high.[21] On January 7, 2014, the temperature in Central Park in New York City was 4 °F (−16 °C). The previous record low for the day was set in 1896, twenty-five years after records began to be collected by the government.[22] Marstons Mills, Massachusetts bottomed out at −9 °F (−23 °C) on the morning of January 8, just one degree above their record low, as did Pittsburgh, which also bottomed out at −9 °F (−23 °C), setting a new record low on January 6–7. Cleveland also set a record low on those dates at −11 °F (−24 °C). Temperatures in Atlanta fell to 6 °F (−14 °C), breaking the old record for January 7 of 10 °F (−12 °C) which was set in 1970. Temperatures fell to −6 °F (−21 °C) at Brasstown Bald, Georgia.[23] Although the cold air moderated, cold temperatures even reached Florida as far south as Tampa which had a low of 33 °F (1 °C) on January 7, 2014, 18 °F (10 °C) below normal.[24]

The period of December 2013–March 2014 around Illinois was the coldest four-month period on record, with average temperatures in Chicago and Rockford, Illinois around the lower 20s to the upper teens.[25]

Canada

The coldest parts of Canada were the eastern prairie provinces, Ontario, Quebec, and the Northwest Territories. However, only southern Ontario set temperature records.

During most of the early cold wave, Winnipeg was the coldest major city in Canada. On January 6, it reached a low of −37 °C (−35 °F), while on January 7, the low was −36 °C (−33 °F). On both days, the temperature did not go above −25 °C (−13 °F). Other parts of southern Manitoba recorded lows of below −40 °C (−40 °F).[26] On January 5, the daily high in Saskatoon was −28.4 °C (−19.1 °F) with a wind chill of −46.[27]

On January 7, 2014, a cold temperature record was set in Hamilton, Ontario: −24 °C (−11 °F);[28] London, Ontario was −26 °C (−15 °F).[29] Toronto dropped below −19 °C (−2 °F) for the first time in 9 years, with a temperature of −22 °C (−8 °F).[30]

Related extreme weather

Heavy snowfall or rainfall occurred on the leading edge of the weather pattern, which travelled all the way from the American Plains and Canadian prairie provinces to the East Coast. Strong winds prevailed throughout the freeze, making the temperature feel at least ten degrees Fahrenheit colder than it actually was, due to the wind chill factor. In addition to rainfall, snowfall, ice, and blizzard warnings, some places along the Great Lakes were also under wind warnings.[31] Europe also saw the 2013-2014 Atlantic winter storms in Europe which has been linked to the cold winter in North America.

United States

On January 3, Boston had a temperature of 2 °F (−17 °C) with a −20 °F (−29 °C) wind chill, and over 7 inches (180 mm) of snow. Boxford, Massachusetts recorded 23.8 inches (600 mm). Fort Wayne, Indiana had a record low of −10 °F (−23 °C). In Michigan, over 11 inches (280 mm) of snow fell outside Detroit and temperatures around the state were near or below 0 °F (−18 °C). New Jersey had over 10 inches (250 mm) of snow, and schools and government offices closed.[32]

On January 5, a storm system crossed the Great Lakes region. In Chicago, where 5 inches (13 cm) to 7 inches (180 mm) of snow had fallen, O'Hare and Midway Airports cancelled 1200 flights.[33] Freezing rain caused a Delta Air Lines flight to skid off a taxiway and into a snowbank at John F. Kennedy International Airport, with no injuries.[34] The storms associated with the Arctic front caused numerous road closures and flight delays and cancellations.[35][citation needed]

By January 8, 2014, John F. Kennedy International Airport had canceled about 1,100 flights, Newark Liberty International Airport had about 600 canceled flights and LaGuardia Airport had about 750–850 flights canceled.

Snowfall was lighter farther south, with between 0.5 and 2 inches (1.3 and 5.1 cm) of snow falling in Tennessee.[36]

In New York City temperatures fell to a record low of 4 °F (−16 °C) on January 7, which broke a 116-year record for daily record low. The cold came after days of unseasonably warm temperatures, with daytime highs dropping by as much as 50 °F (28 °C) overnight, as highs were 55 °F (13 °C) early on January 6. This made it the most extreme temperature swing in New York City since March 1921.[37] The afternoon high was only 10 °F (−12 °C).[38] Also on January 7, the day after a record-setting 3 °F (−16 °C), Chicago recorded −12 °F (−24 °C).[39] Embarrass, Minnesota had the coldest temperature in the lower 48 states March 2014 with −35 °F (−37 °C).[40]

Canada

In Canada, the front brought rain and snow events to most of Canada on January 5 and 6, which became the second nor'easter in less than a week in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.[41] This weather event ended when the front pushed through, bringing the bitterly cold temperatures with it. Southwestern Ontario experienced a second round of heavy snow in the wake of the front throughout January 6 and 7 and part of January 8 due to lake-effect snow.[42] The Northwest Territories and Nunavut did not experience record-breaking cold, but had a record-breaking blizzard on January 8, when the freeze further south was coming to an end.[citation needed]

Much of Ontario and Quebec were under blizzard warnings.[43] Many highways in Southwestern Ontario were closed by heavy lake-effect snowfall.[citation needed]

Nearly all parts of Canada under the deep freeze experienced steady winds around 30 to 40 kilometres per hour (19 to 25 mph). In some areas along the north shore of Lake Erie, those winds reached 70 km/h (43 mph), with gusts as high as 100 km/h (62 mph).[31] This brought local wind chill levels as low as −48 °C (−54 °F)[44]

Several Ontario locations along Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence Valley experienced cryoseisms or frost quakes.[45]

Mexico

Cold air rushing into the Gulf of Mexico behind the front created a Tehuano wind event, with northerly winds from the Bay of Campeche to the Gulf of Tehuantepec in Mexico reaching 41 kn (76 km/h; 47 mph).[46] Saltillo, in the northeast of the country, registered freezing drizzle and a temperature as low as −6 °C (21 °F).[47]

On January 29, Monterrey registered −1 °C (30 °F) and snow grains with 1 centimetre (0.39 in) of snowy accumulation.[48]

Impact

The extreme cold weather grounded thousands of flights and seriously affected other forms of transport. Many power companies in the affected areas asked their customers to conserve electricity.[49]

United States

The weather event played a significant role in the US Economy contributing to a 2.9% drop in GDP. "The bad weather in much of the U.S. in early 2014 was a significant drag on the economy, disrupting production, construction, and shipments, and deterring home and auto sales", wrote PNC Senior Economist Gus Faucher in a note out prior to the release. "But data show growth rebounding in the second quarter, with improvements in home and auto sales and residential construction."[50]

Evan Gold of weather intelligence firm Planalytics called the storm and the low temperatures the worst weather event for the economy since Hurricane Sandy just over a year earlier.[51] 200 million people were affected, and Gold calculated the impact at $5 billion.[51] $50 to $100 million was lost by airlines which cancelled a total of 20,000 flights after the storm began on January 2.[51] JetBlue took a major hit because 80 percent of its flights go through New York City or Boston.[51] Tony Madden of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis said with so many schools closed, parents had to stay home from work or work from home. Even the ones who could work from home, Madden said, might not have done as much.[51] Not included in the total were the insurance industry and government costs for salting roads, overtime and repairs. [citation needed]

Gold said some industries benefitted from the storm and cold, including video on demand, restaurants which offered delivery services and convenience stores.[51] People also used gift cards to buy online.[51] Hopper Research of Boston observed that searches for flights to Cancun, Mexico increased by about half in northern cities.[52] New England spot natural gas prices hit record levels from January 1 to February 18, with the day-ahead wholesale (spot) natural gas price at the Algonquin Citygate hub serving Boston averaging US$22.53 per million British thermal units ($76.9/MWh), a record high for these dates since the Intercontinental Exchange data series began in 2001.[53]

Over a dozen deaths were attributed to the cold wave, with dangerous roadway conditions and extreme cold cited as causes.[12][54][55]

At least 3,600 flights were cancelled on January 6, and several thousand were cancelled over the preceding weekend.[6] Further delays were caused by the weather at airports that did not possess de-icing equipment.[56] At O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, the jet fuel and deicing fluids froze,[9] according to American Airlines spokesman Matt Miller.[57]

Amtrak cancelled scheduled passenger rail service having connections through Chicago, due to heavy snows or extreme cold.[58] Three Amtrak trains were stranded overnight on January 6, approximately 80 miles (130 km) west of Chicago, near Mendota, Illinois, due to ice and snowdrifts on the tracks. The 500 passengers were loaded onto buses the next morning for the rest of the trip to Chicago.[59][60] Another Amtrak train was stuck near Kalamazoo, Michigan for 8 hours, while en route from Detroit to Chicago.[59] Chicago Metra commuter trains reported numerous accidents.[9] Detroit shut down its People Mover due to the low temperatures on January 7.[61]

Between January 5 and 6, temperatures fell 50 °F (28 °C) in Middle Tennessee, dropping to a high of 9 °F (−13 °C) on Monday, January 6 in Nashville. During the cold wave, the strain on the power supply left 1,200 customers in Nashville without power, along with around 7,500 customers in Blount County.[36][62] The Tennessee Emergency Management Agency declared a state of emergency.[36]

Twenty-four thousand residents lost power in Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri.[63]

The Weather Channel reported power outages in several states, abandoned cars on highways in North Carolina, and freezing rain in Louisiana.[64]

Canada

A power failure in Newfoundland, late on January 5, left 190,000 customers without electricity. Most of the outages were restored by the following day.[65]

Air transportation was delayed out of airports in Montreal and Ottawa, as well as completely cancelled at Toronto Pearson International Airport, due to concerns about de-icing.[66][67]

Ecological

Early news reporting suggested that the severe cold would cause high mortality among the emerald ash borer based on the opinion of a US Department of Agriculture spokesperson suggesting "The progressive loss of ash trees in North America due to this insect has probably been delayed by this deep freeze."[68] This has been widely repudiated based on scientific studies of underbark temperature tolerances of emerald ash borer in Canada.[69][70][71]

Government response

The weather affected schools, roads, and public offices.[72]

United States

In Minnesota, all public schools statewide were closed on January 6 by order of Governor Mark Dayton.[73] This had not been done in 17 years.[74] In Wisconsin, schools in most (if not all) of the state were closed on January 6 as well as on January 7.[75] When the second cold wave emerged, schools were also closed on January 27 and 28.[76] In Michigan, the mayor of Lansing, Virg Bernero, issued a snow emergency prohibiting all non-essential travel as well as closing down non-essential government offices.[77] In Indiana, more than fifty of the state's ninety-two counties, including virtually everywhere north of Indianapolis, closed all roads to all traffic except emergency vehicles.[78] In Ohio, schools across the entire state were closed on January 6 and 7, including the state's largest two school districts, Columbus City Schools and Cleveland Metropolitan School District.[79] Ohio State University completely shut down on January 6 and 7, delaying the start of the spring semester by two days for the first closure on two consecutive days in 36 years.[80]

On March 4, 2014, the United States House of Representatives passed the Home Heating Emergency Assistance Through Transportation Act of 2014 (H.R. 4076; 113th Congress) in reaction to the extreme cold weather.[81] The bill, if it becomes law, would create an emergency exception to existing Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration regulations.[82] The exceptions would allow truckers to drive for long hours if they are delivering home heating fuels, such as propane, to places where there is a shortage.[81] The exemption would last until May 31, 2014.[83] An existing suspension was scheduled to expire on March 15, 2014.[84] According to Majority Leader Eric Cantor, the issue of household energy costs need to be addressed because "the Energy Information Administration predicted that 90 percent of U.S. households would see higher home heating costs this year, and low income families already spend 12 percent of their household budget on energy costs."[81] Rep. Shuster argued in favor of the bill saying that it "will provide relief for millions of Americans suffering from the current propane and home heating fuel emergency".[83] According to the Congressman, an "exceptionally cold winter" increased demand on propane, "which is used for heating approximately 12 million homes in the United States".[83]

Canada

Schools in much of Southern Ontario and rural Manitoba were closed on both January 6 and 7 because of the combined threat of extreme cold, strong winds, and heavy snowfall. Outside the areas of heavy snowfall, schools remained open both days.[85]

Hamilton and Toronto issued Extreme Cold Weather Alerts and Ottawa issued a Frostbite Alert, which both open up additional shelter spaces for the homeless.[86][87]

In Quebec, all public services remained open, with the exception of tutoring and any other services requiring exterior relocation.[citation needed]

Role of climate change

Research on a possible connection between individual extreme weather events and long-term anthropogenic climate change is a new topic of scientific debate.[88] Prior to the events of January 2014, several studies on the connection between extreme weather and the polar vortex were published suggesting a link between climate change and increasingly extreme temperatures experienced by mid-latitudes (e.g., central North America).[89] This phenomenon has been suggested by some to result from the rapid melting of polar sea ice, which replaces white, reflective ice with dark, absorbent open water (i.e., the albedo of this region has decreased). As a result, the region has heated up faster than other parts of the globe. With the lack of a sufficient temperature difference between Arctic and southern regions to drive jet stream winds, the jet stream may have become weaker and more variable in its course, allowing cold air usually confined to the poles to reach further into the mid latitudes.[90][91][92][93]

This jet stream instability brings warm air north as well as cold air south. The patch of unusual cold over the eastern United States was matched by anomalies of mild winter temperatures across Greenland and much of the Arctic north of Canada,[94] and unusually warm conditions in Alaska.[95] A stationary high pressure ridge over the North Pacific Ocean kept California unusually warm and dry for the time of year, worsening ongoing drought conditions there.[96]

Research has led to a good documentation of the frequency and seasonality of sudden warmings: just over half of the winters since 1960 have experienced a major warming event in January or February".[97] According to Charlton and Polvani[98] sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) in the Arctic has occurred during 60% of the winters since 1948 and 48% of these SSW events have led to the splitting of the polar vortex, leading to the same type of Arctic cold front that happened in January 2014.

A 2001 study found that "there is no apparent trend toward fewer extreme cold events in Europe or North America over the 1948–99 period, although a long station history suggests that such events may have been more frequent in the United States during the late 1800s and early 1900s."[98] A 2009 MIT study found that such events are increasing and may be caused by the rapid loss of the Arctic ice pack.[99]

SSW events of similar magnitude occurred in 1985 in North America, and in 2009 and 2010 in Europe.

Extended cold

United States

The NOAA's National Climatic Data Center found that since modern records began in 1895, the period from December 2013 through February 2014 was the 34th-coldest such period for the contiguous 48 states as a whole. They also found 91% of the Great Lakes were iced over, the second highest percentage on record.[100] Ice on the Great Lakes did not fully melt until early June.[101] That was the latest date of ice on the Great Lakes ever.[102]

The average temperature for the contiguous U.S. during the winter season was 31.3 °F (−0.4 °C), one degree below the 20th-century average, and the number of daily record-low temperatures outnumbered the number of record-high temperatures nationally in early 2014.[100]

In contrast, California had its warmest winter on record, being 4.4 °F (2.4 °C) above average, while the first two months of 2014 were the warmest on record in Fresno, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Nevada, Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona.[100]

In addition, while December through February was the ninth driest on record for the contiguous 48 states dating to 1895, chiefly due to extremely dry conditions in the West and Southwest, yet Winter snow cover areal extent was the 10th-largest on record for same 48 states, dating to 1966. New York City,[103] Philadelphia,[104] and Chicago[105] all had one of their ten snowiest winters, while Detroit had its snowiest winter on record.[106][107][108] Aside from persistence due to lack of melting, the lower temperatures may have had some impact—whilst snowfall has an average moisture content ratio of 10:1 (one inch of moisture producing 10 inches of snow), it can range from 3:1 to 100:1, generally rising with falling temperatures, documented instances in the North Central states of snowfalls with ratios from 75:1[109] up towards the maximum possible of 100:1 were observed and those in excess of 30:1 were rather common because of the temperatures in which the snow formed and fell.

Many cities experienced their coldest February in many years:

- Rochester, Minnesota experienced its fourth-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 6.7 °F (−14.1 °C)

- Green Bay, Wisconsin saw its third-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 8 °F (−13 °C)

- Minneapolis-St. Paul tied its record for the seventh-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 8.6 °F (−13.0 °C)

- Dubuque, Iowa realized its third-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 10 °F (−12 °C)

- Madison, Wisconsin saw its tenth-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 12.2 °F (−11.0 °C)

- Moline, Illinois tied its record for the fifth-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 14.6 °F (−9.7 °C)

- Fort Wayne, Indiana experienced its sixth-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 17.6 °F (−8.0 °C)

- Peoria, Illinois saw its sixth-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 17.9 °F (−7.8 °C)

- Kansas City, Kansas had its ninth-coldest February, with a monthly average temperature of 24.7 °F (−4.1 °C)[110]

Daily record lows were set on February 28 in Gaylord, Michigan at −29 °F (−34 °C), Green Bay, Wisconsin with −21 °F (−29 °C), Flint, Michigan at −16 °F (−27 °C), Grand Rapids, Michigan −12 °F (−24 °C), and Toledo, Ohio at −7 °F (−22 °C) while Newberry, Michigan dipped to −41 °F (−41 °C).[citation needed] In the New York Metropolitan Area, record lows were broken or tied in Islip, Bridgeport and John F. Kennedy International Airport.[111]

During the official meteorological winter season of December through February, Brainerd, Minnesota averaged a meager 1.7 °F (−16.8 °C), and realized its third-coldest winter in recorded history. Similarly, the average temperature in Duluth, Minnesota was 3.7 °F (−15.7 °C), ranking this winter as its second-coldest.[112]

The first week of March 2014 also saw remarkably low temperatures in many places, with 18 states setting all-time records for cold. Among them was Flint, Michigan, which reached −16 °F (−27 °C) March 3, and Rockford, Illinois at −11 °F (−24 °C).[113] Baltimore also recorded their coldest ever temperature in March, at 4 °F (−16 °C).[114]

The entire December–March period in Chicago was the coldest on record, topping the previous record from 1903 to 1904, even colder than the notoriously cold winters of the late 1970s.[115] The average temperature in Chicago from December 1, 2013, to March 31, 2014, was 22 °F (−6 °C), 10 °F (5.6 °C) below average.[116]

The state of Iowa went through its ninth-coldest winter in 141 years. Only the winters of 1935–36 and 1978–79 in the last century were colder, with the others being back in the 1880s.[117]

March 2014 was the coldest on record in Vermont, and second coldest for New Hampshire and Maine. The temperature was 18.3 °F (−7.6 °C) on average in Vermont.[118]

Despite the abnormally cold winter over sections of North America and much of Russia, most of the globe saw either average or above-average temperatures during the first four months of 2014.[119] In fact, during the cold wave, North America saw much colder temperatures than Sochi, Russia which during the time was hosting the 2014 Winter Olympics.[120][121]

During the last week of March, meteorologists expected average temperatures to return sometime from April to mid-May.[1] On April 10, 2014, a ridge of high pressure moved into the Eastern United States, bringing average and above-average temperatures to the region, which ended the cold wave. But even as late as April 15, snow showers still occurred in New York City.[122] As such, even April fell below average, and the first time in 2014 that New York City had an above average month was May.[123] This contributed to 2014 being slightly below average in New York City.[124]

Canada

As of February 27, Winnipeg was experiencing the second-coldest winter in 75 years, the coldest in 35 years and with snowfall total being 50 per cent more than normal. Saskatoon was experiencing the coldest winter in 18 years; Windsor, Ontario, the coldest winter in 35 years and snowiest winter on record; Toronto, the coldest winter in 20 years; St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, the coldest winter in 20 years, the snowiest winter in seven years and a record number of stormy days. Vancouver, which is known for its milder weather, was realizing one of its coldest and snowiest Februarys in 25 years.[125] On February 28, Hamilton, Ontario set a record low of −22 °C (−8 °F).[126]

In 2014 the U.S. winter period December – February had experienced its coldest in 25 years, while Canada had its warmest winter on record.[127]

See also

- January 1998 North American ice storm

- December 2013 North American storm complex

- January 2014 Gulf Coast winter storm

- February 11–17, 2014 North American winter storm

- 2013–14 North American winter storms

- 2014–15 North American winter

- November 2014 Bering Sea cyclone

- November 2014 North American cold wave

References

- ^ a b "Rough Winter to Lag into March for Midwest, East". AccuWeather.

- ^ "Cost of the cold: 'polar vortex' spell cost US economy $5bn". The Guardian. Associated Press. January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. polar vortex sets record low temps, kills 21". CBC News. January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Polar Air Blamed For 21 Deaths Nationwide". Chicago Defender. January 8, 2014.

- ^ Gutro, Rob (January 6, 2014). "Polar Vortex Enters Northern U.S." Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "N America weather: Polar vortex brings record temperatures". BBC News – US & Canada. BBC News Online. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Calamur, Krishnadev (January 5, 2014). "'Polar Vortex' Brings Bitter Cold, Heavy Snow To U.S." The Two Way. National Public Radio. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Preston, Jennifer (January 6, 2014). "'Polar Vortex' Brings Coldest Temperatures in Decades". The Lede. The New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c Associated, The. "5 Things To Know About The Record-Breaking Freeze". NPR. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Spotts, Pete (January 6, 2014). "How frigid 'polar vortex' could be result of global warming (+video)". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Freezing US – Is the Polar Vortex to Blame?". BBC Weather. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014.

- ^ a b DeMarche, Edmund (January 4, 2014). "'Polar vortex' set to bring dangerous, record-breaking cold to much of US". FoxNews.com. Fox News. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Big freeze grips United States, disrupting travel and business". Grand Forks Herald. January 6, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ "Chicago Gripped By Record Cold; Schools Closed, Public Transit Delayed". WBBM-TV. January 5, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "'It's too darn cold': Historic freeze brings rare danger warning". CNN. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Metra plans on normal schedule for evening rush; CPS classes to resume Wednesday". Chicago Sun-Times. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "'ChiBeria,' Chicago's biggest chill in nearly 20 years, headed our way". WLS. January 5, 2014. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Ask Tom why: What was the lowest wind chill ever recorded in Chicago?". Chicago Tribune. January 18, 2011. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (January 10, 2014). "Weather wimps?". Salisbury Post. Associated Press. p. 1A.

- ^ Doyle Rice (January 7, 2014), List of record-low temperatures set Tuesday USA Today

- ^ Coldest Arctic Outbreak in Midwest, South Since the 1990s Wrapping Up, weather.com, Jon Erdman and Nick Wiltgen, January 8, 2014

- ^ "Extreme Cold Wave Invades Eastern Half of U.S." Weather Underground. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Record-setting cold turns deadly Archived January 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Macon Telegraph January 7, 2014

- ^ "Tampa weather: history". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ "Coldest December-March Period in Chicago History".

- ^ Daily Data Report for January 2014 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Canada government site

- ^ "Daily Data". Climate.weather.gc.ca. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "At −24 C, Hamilton sets cold temperature record – Latest Hamilton news – CBC Hamilton". Cbc.ca. January 19, 1994. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "London January Weather 2014 – AccuWeather Forecast for Ontario Canada". Accuweather.

- ^ "Historical Data - Climate - Environment and Climate Change Canada". October 31, 2011.

- ^ a b "Alerts for: Simcoe – Delhi – Norfolk – Environment Canada". Weather.gc.ca. April 16, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Snow, cold disrupt large swath of US; more to come". Boston Globe. Associated Press. January 3, 2014. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Winter storm 2014 strikes Midwest, Northeast; Snow storm 'Hercules' followed by 'polar vortex'". WLS-TV. January 5, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Fitzsimmons, Emma G. (January 5, 2014). "Jet Skids into Snowbank at J.F.K. ad Airport". The New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Fierce weather forces more flight cancellations, delays". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 5, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Dangerously Cold Temperatures Settle into Mid-State". WTVF NewsChannel 5. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Barron, James (January 6, 2014). "Polar Vortex: Temperatures Fall Far, Fast". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Associated Press, The (January 7, 2013). "Record low temperatures in New York City". Fox News. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Weather History for Chicago, IL". The Weather Channel.

- ^ "US weather: all 50 states fall below freezing". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Deep freeze extends from Winnipeg east to Newfoundland". Cbc.ca. January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Schools closed, blizzard warning continued". The London Free Press. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Weather Alerts – Environment Canada". Weather.gc.ca. December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ North America's big freeze seen from space BBC News, January 9, 2014

- ^ "'Frost quakes' wake Toronto residents on cold night – Toronto – CBC News". Cbc.ca. January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Satellite Blog, CIMSS (January 3, 2014). "Tehuano wind event in the wake of a strong eastern US winter storm". Space Science and Engineering Center. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Synop report summary". Saltillo: Ogimet. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "76393: Monterrey, N. L. (Mexico)". Professional information about meteorological conditions in the world. Ogimet. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ "NERC on Polar Vortex Performance: Good, Could be Better". RTO Insider. September 30, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. GDP Dropped 2.9% In The First Quarter 2014, Down Sharply From Second Estimate". Forbes. June 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Deep freeze may have cost economy about $5 billion, analysis shows". The Durango Herald. January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Karnowski, Stevework (January 9, 2014). "Deep freeze may have cost economy about $5 billion". News & Observer. Associated Press. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ EIA. "Today in Energy". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Castellano, Anthony (January 3, 2013). "At Least 13 Died in Winter Storm That Dumped More Than 2 Feet of Snow Over Northeast". ABC News.

- ^ "North America arctic blast creeps east". BBC News. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "OIA Can't Deice Frozen Jets". AviationPros.com. January 7, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Kyle Arnold (January 6, 2014). "Sky Writer: Frozen aircraft fuel stalling nationwide air travel". Tulsa World. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

American Airlines said Monday that it's so cold in Chicago that airline fuel is freezing and they can't refuel planes. 'Fuel and glycol supplies are frozen – at ORD (Chicago's O'Hare) and other airports in the Midwest and Northeast,' said American Airlines spokesman Matt Miller.

- ^ "Service Alert". Amtrak. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Passengers stuck on Amtrak train 8 hours; Amtrak cancels some Chicago train service". WLS-TV. January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "500 passengers spend night on stranded Amtrak trains". Chicago Tribune. WGN-TV. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Bone-Chilling Temps Shut Down Detroit People Mover, CBS News, January 7, 2014

- ^ Hayley Harmon (January 4, 2014). "Cold weather knocks out power for 7500 Blount County residents". WATE News. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ 'Historic and life-threatening' freeze brings rare danger warning, CNN, January 6, 2014

- ^ "Winter Storm Pax Update: Hundreds of Thousands Lose Power, Drivers Abandoning Cars on Charlotte and Raleigh Highways". The Weather Channel. February 12, 2014. Archived from the original on February 11, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ CTVNews.ca Staff (January 6, 2014). "Power restored to majority of customers in Newfoundland". CTV News. Bell Media. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Pearson airport delays: What you need to know". CBC News. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Extreme cold causes more delays, cancellations at Pearson". CP24. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Ziezulewicz, Geoff (January 6, 2014). "Cold weather could limit ash borer threat". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Purvis, Micheal (February 28, 2014). "Deer in danger from cold weather, but emerald ash borer likely not significantly affected, say scientists". The Sault Star. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Spears, Tom (February 4, 2014). "False hope: Deep freeze poses no threat to tree-munching emerald ash borer". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Vermunt, Bradley; Cuddington, Kim; Sobek-Swant, Stephanie; Crosthwaite, Jill (2012). "Cold temperature and emerald ash borer: Modelling the minimum under-bark temperature of ash trees in Canada". Ecological Modelling. 235–236: 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.03.033.

- ^ Livingston, Ian (January 7, 2014). "Polar vortex delivering D.C.'s coldest day in decades, and we're not alone". Washington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Gov. Orders Schools Closed Monday Over Dangerous Cold". CBS. January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "'Polar vortex' set to bring dangerous, record-breaking cold to much of US". Fox News. January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Richards, Erin (January 7, 2014). "2nd day of school closings cuts into planned snow days". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Vielmetti, Bruce. "Dangerous blast of cold leads to more school closings". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "Mayor Declares Snow Emergency" (Press release). Office of Mayor Virg Bernero, Lansing, MI. January 5, 2014. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "County Travel Status for 01/06/2014 00:20:11 EDT" (PDF). Indiana Department of Homeland Security. January 6, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Temperatures continue to drop; districts cancel school". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Frosty weather keeps Ohio State closed for a 2nd straight day". The Lantern. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c Kasperowicz, Pete (February 28, 2014). "Cold snap prompts wave of energy bills". The Hill. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "H.R. 4076 – Summary". United States Congress. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Kasperowicz, Pete (March 4, 2014). "House votes to ease access to home heating oil". The Hill. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Mauriello, Tracie (March 4, 2014). "Fuel-trucker bill advances". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "Hamilton board defends decision to keep schools open". Cbc.ca. January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Extreme cold weather alert for Toronto". CTV News. December 16, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ Cold weather Resource Kit City of Ottawa official site

- ^ Sobel, Adam (January 7, 2014). "Record cold doesn't disprove global warming". CNN. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^

- Baldwin, M. P.; Dunkerton, TJ (2001). "Stratospheric Harbingers of Anomalous Weather Regimes". Science. 294 (5542): 581–4. Bibcode:2001Sci...294..581B. doi:10.1126/science.1063315. PMID 11641495. S2CID 34595603.

- Song, Yucheng; Robinson, Walter A. (2004). "Dynamical Mechanisms for Stratospheric Influences on the Troposphere". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 61 (14): 1711–25. Bibcode:2004JAtS...61.1711S. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(2004)061<1711:DMFSIO>2.0.CO;2.

- Overland, James E. (2013). "Atmospheric science: Long-range linkage". Nature Climate Change. 4 (1): 11–2. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4...11O. doi:10.1038/nclimate2079.

- Tang, Qiuhong; Zhang, Xuejun; Francis, Jennifer A. (2013). "Extreme summer weather in northern mid-latitudes linked to a vanishing cryosphere". Nature Climate Change. 4 (1): 45–50. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4...45T. doi:10.1038/nclimate2065.

- Screen, J A (2013). "Influence of Arctic sea ice on European summer precipitation". Environmental Research Letters. 8 (4): 044015. Bibcode:2013ERL.....8d4015S. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/044015.

- Francis, Jennifer A.; Vavrus, Stephen J. (2012). "Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (6): n/a. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..39.6801F. doi:10.1029/2012GL051000.

- Petoukhov, Vladimir; Semenov, Vladimir A. (2010). "A link between reduced Barents-Kara sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (D21): D21111. Bibcode:2010JGRD..11521111P. doi:10.1029/2009JD013568.

- Masato, Giacomo; Hoskins, Brian J.; Woollings, Tim (2013). "Winter and Summer Northern Hemisphere Blocking in CMIP5 Models". Journal of Climate. 26 (18): 7044–59. Bibcode:2013JCli...26.7044M. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00466.1.

- Wang, L.; Chen, W. (2010). "Downward Arctic Oscillation signal associated with moderate weak stratospheric polar vortex and the cold December 2009". Journal of Geophysical Research. 37 (9): 581–4. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..37.9707W. doi:10.1029/2010GL042659.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (January 6, 2014). "Polar Vortex: Climate Change Might Just Be Driving the Historic Cold Snap". Time. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Friedlander, Blaine (March 4, 2013). "Arctic ice loss amplified Superstorm Sandy violence". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Spotts, Pete (January 6, 2014). "How frigid 'polar vortex' could be result of global warming (+video)". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^

- Wetzel, G; Oelhaf, H.; Kirner, O.; Friedl-Vallon, F.; Ruhnke, R.; Ebersoldt, A.; Kleinert, A.; Maucher, G.; Nordmeyer, H.; Orphal, J. (2012). "Diurnal variations of reactive chlorine and nitrogen oxides observed by MIPAS-B inside the January 2010 Arctic vortex". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 12 (14): 6581–6592. Bibcode:2012ACP....12.6581W. doi:10.5194/acp-12-6581-2012.

- Weng, H. (2012). "Impacts of multi-scale solar activity on climate. Part I: Atmospheric circulation patterns and climate extremes". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 29 (4): 867–886. Bibcode:2012AdAtS..29..867W. doi:10.1007/s00376-012-1238-1. S2CID 123066849.

- Lue, J.-M.; Kim, S.-J.; Abe-Ouchi, A.; Yu, Y.; Ohgaito, R. (2010). "Arctic Oscillation during the Mid-Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum from PMIP2 Coupled Model Simulations". Journal of Climate. 23 (14): 3792–3813. Bibcode:2010JCli...23.3792L. doi:10.1175/2010JCLI3331.1.

- Zielinski, G.; Mershon, G. (1997). "Paleoenvironmental implications of the insoluble microparticle record in the GISP2 (Greenland) ice core during the rapidly changing climate of the Pleistocene-Holocene transition". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 109 (5): 547–559. Bibcode:1997GSAB..109..547Z. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1997)109<0547:PIOTIM>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Andrew Freedman (January 2, 2014). "Arctic Outbreak: When the North Pole Came to Ohio".

- ^ Barron-Lopez, Laura (January 6, 2014). "Is global warming behind polar vortex?". The Hill. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ More on the Drought; The Numbers Are Frightening AccuWeather, January 6, 2014

- ^ GEOS-5 Analyses and Forecasts of the Major Stratospheric Sudden Warming of January 2013 NASA

- ^ a b Extreme Cold Outbreaks in the United States and Europe, 1948–99 American Meteorological Society June 2001

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (January 6, 2014). "Climate Change Might Just Be Driving the Historic Cold Snap". Time. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c February 2014 National Climate Report, National Centers for Environmental Information

- ^ Great Lakes Ice Free, At Last, in June!, The Weather Channel, June 10, 2014

- ^ Toledo area only site on Great Lakes warm enough to swim — at least now, Toledo Blade, June 13, 2014

- ^ "Monthly & Seasonal Snowfall at Central Park". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ Erdman, Jon. "NOAA: Winter 2013–2014 Among Coldest on Record in Midwest; Driest, Warmest in Southwest". The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Rice, Doyle (March 13, 2014). "Numbing numbers: U.S. had coldest winter in 4 years". USA Today. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ MWS Milwaukee-Sullivan January 13, 2014

- ^ Dolce, Chris. "10 Cities Where February Could Rank as a Top 10 Coldest". Winter Storm Central. The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Arctic Front Brings Record-Breaking Cold, Howling Winds, NBC New York, February 28, 2014

- ^ Richardson, Renee (March 5, 2014). "2013–14 winter ranks third for all-time coldest". Brainerd Dispatch. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Dolce, Wiltgen, Chris, Nick. "Winter Won't Give Up: Now 18 States With All-Time Record March Cold". March 6, 2014. Weather Underground, Inc. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ BWI hits 4 degrees, coldest-ever reading for March, Baltimore Sun, March 4, 2014

- ^ "It Was a Record-Cold March From Northern Great Lakes to Northern New England". Apr 2, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Chicago Had Its Coldest Winter on Record in Over A Century". Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Hillaker, Harry (March 12, 2014). "AGRIBUSINESS: Iowa Goes Through Ninth Coldest Winter". March 12, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ March 2014 National Climate Report, NOAA

- ^ Sosnowski, Alex. "Rough Winter to Lag into March for Midwest, East". AccuWeather.

- ^ "2014 Winter Olympics: Ten places colder than Sochi right now". Slate. February 16, 2014.

- ^ "theScore".

- ^ Let’s Not Even Talk About How It Snowed Last Night, New York Inteligencer, April 16, 2014

- ^ "NYC Monthly Summary: May 2014". June 3, 2014.

- ^ "NYC 2014: A Year of Weather in Review". January 3, 2015.

- ^ CTVNews.ca Staff (February 27, 2014). "This winter is miserable: meteorologists have confirmed it". February 27, 2014. Bell Media. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ "Hamilton sets cold record for Feb. 28". CBC. February 28, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Masters, Dr. Jeff. "An upside-down winter: coldest in 25 years in U.S., warmest on record in Canada". Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- 2013–14 North American winter

- 2014 disasters in Canada

- 2014 cold waves

- 2014 natural disasters in the United States

- Climate change controversies

- Cold waves in Canada

- Cold waves in the United States

- Climate change in Canada

- Climate change in the United States

- January 2014 events in North America

- Natural disasters in Tennessee

- Natural disasters in Ontario