Modern Jewish historiography

Modern Jewish historiography is the scholarly analysis of Jewish history in the early modern period and into the modern era. While Jewish oral history and the collection of commentaries in the Midrash and Talmud are ancient, with the rise of the printing press and moveable type in the medieval era, Jewish histories and early editions of the Hebrew Bible were published which dealt with the history of the Jewish religion, and increasingly, national histories of the Jewish people. Jewish historians wrote accounts of their collective traumas, but also increasingly used history for political, cultural, and scientific or philosophical exploration. Writers drew upon a corpus of culturally inherited text in seeking to construct a logical narrative to critique or advance the state of the art. Modern Jewish historiography intertwines with intellectual movements such as the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment but drew upon earlier works in the Late Middle Ages and into diverse sources in antiquity.

Background

The major publications in Jewish history in the early modern period were influenced by the political climate of their respective times.[2][3][4][5][6] Certain Jewish historians, acting on a desire to achieve Jewish equality, used Jewish history as a tool towards Jewish emancipation and religious reform. “Envisaging Jewish identity as essentially religious, they created a Jewish past that focused on Jewish religious rationality, and stressed Jewish integration within the societies in which Jews lived.”[7]

Talmudic authorities such as Joseph Caro and the Geonim discouraged the writing of history in the medieval and early modern era, and some attempts were met with controversy.[8] Secular philosophy was seen as a gentile activity and forbidden.[9] Baruch Spinoza was excommunicated for transgressing the bounds of Rabbinic thought into the growing domain of Enlightenment philosophy in 1656.[10] Spinoza and other heretics such as Abraham Abulafia or ibn Caspi became figures in the conflict between emancipation and traditionalism in Jewish political and historical ideology.[11][12] Israël Salvator Révah, per Marina Rustow, has stressed that the anti-rabbinic themes expressed by both Uriel da Costa (1585-1640) and Spinoza had emerged from the crucible of Iberian crypto-Jewish culture.[13] Early modern philology (i.e. the study of historical texts) had an important impact on the development of the Enlightenment intellectual movements through work such as that of Spinoza.[14] Richard Simon also had his work of historical biblical criticism suppressed by the Catholic authorities in France in 1678.[15]

Jews of the medieval Islamic world such as Andalusia, North Africa, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq were prolific producers and consumers of historical works in Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Arabic and rarely Aramaic.[16] Iggeret of Rabbi Sherira Gaon (987)[17][18][19] and Sefer ha-Qabbalah (1161)[20] by Abraham ibn Daud (ibn David)[21] were two medieval sources available to and trusted by Jewish early modern historians.[22][23][24]

Josippon (or Sefer/Sepher Josippon), also called "Josephus of the Jews," was a key medieval source familiar to Hasdai ibn Shaprut and Ibn Hazm, one of if not the most influential historical works in pre-modern Jewish historiography, probably composed by a pseudonymous "Joseph ben Gorion" in the 10th century based on the earlier Josephus Flavius and his work Antiquities of the Jews.[25][26] It relies on the Hegesippus (or Pseudo-Hegesippus), a Latin translator of Antiquities and Josephus' The Jewish War.[27] Like its namesake and inspiration, the work commingles Roman history and Jewish history.[28] Yosippon was republished in the 16th century and was a historical chronicle of critical importance to medieval Jews.[29] It was relied on by Abraham ibn Ezra and Isaac Abravanel.[30] These books were frequently reprinted through the 18th century.[31][32][33][34][35][36] The work emerged out of the context of Hellenistic Judaism or Romaniote Judaism in the Jewish Byzantine Empire.[37]

The version of Josippon by the young Balkan scholar Yehudah ibn Moskoni (1328-1377), printed in Constantinople in 1510 and translated to English in 1558, became the most popular book published by Jews and about Jews for non-Jews, who ascribed its authenticity to the Roman Josephus, until the 20th century.[38] Born in Byzantium, Moskoni's library was once considered by historians to be the largest individual Jewish library in medieval Western Europe, although as Eleazar Gutwirth notes, there were numerous Jewish and converso libraries 1229-1550, citing Jocelyn Nigel Hillgarth. He further notes that Moskoni's library was sold in 1375 for a high price, and that Moskoni specifically commented on the use of non-Jewish sources in Josippon.[39]

Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) 's Muqaddimah (1377) also contains a post-biblical Jewish history of the "Israelites in Syria" and he relied on Jewish sources, such as the Arabic translation of Josippon by Zachariah ibn Said, a Yemenite Jew, according to Khalifa (d. 1655).[40][41] Saskia Dönitz has analyzed an earlier Egyptian version older than the version reconstructed by David Flusser, drawing on the work of a parallel Judaeo-Arabic Josippon by Shulamit Sela and fragments in the Cairo Geniza, which indicate that Josippon is a composite text written by multiple authors over time.[42][43][44][45][46]

Josippon was also a popular work or a volksbuch, and had further influence such as its Latin translation by Sebastian Munster which was translated into English by Peter Morvyn printed by Richard Jugge, printer to the Queen in England, and according to Lucien Wolf may have played a role in the resettlement of the Jews in England.[47][48] Munster also translated the historical work of ibn Daud which was included with Morwyng's edition.[49] Steven Bowman notes that Josippon is an early work of Jewish nationalism which had a significant influence on midrashic literature and talmudic chroniclers as well as secular historians, though considered aggadah by mainstream Jewish thought, and acted as an ur-text for 19th century efforts in Jewish national history.[38]

Jewish expulsions accelerated in the 15th century and influenced the growth in Jewish historiography.[50][13] Sephardic Jews from Spain, Portugal, and France settled in Italy and the Ottoman Empire during this period, shifting the nexus of Jewry east.[51]

Early modern histories in the post-medieval and Renaissance era

The 16th century is considered something of a blossoming of Jewish historiography by some historians, such as Yerushalmi, who characterizes the focus as shifting social and post-biblical.[29][52] Although some historians focus on the 19th century as an important period in the development of modern Jewish historiography, the 16th century is also considered an important period.[53] The Haskalah, or Jewish enlightenment, became interested in Sephardic Jewish sources and had an idea of historiography with an eye toward reformism.[54][55] Religion figured prominently and the differences in martyrdom and messianic figures in Sephardic and Askenazic communities post-expulsion are the subject of historiographical debate.[56] Some historians, such as Bonfil, have disagreed with Yerushalmi that this period produced a significant sea change in historiography.[57][58]

The Book of the Honeycomb's Flow (1476) by Judah Messer Leon (c.1420-1498) (Judah ben Jehiel, alias Leone di Vitale) is an early work of humanistic classical rhetorical analysis that was also noted by Graetz, which was noted by Bonfil, and paraphrasing Israel Zinberg stated, he "was a child not only of the old people of Israel, but also of the youthful Renaissance." Nofet Zufim drew on the classical theoretical writings of Cicero, Averroes and Quintilian[59] While not a work of history, it was a precursor to de Rossi and cited by him as opening the door to the value of secular studies. It was printed by Abraham Conat.[60]

Solomon ibn Verga (1460-1554)'s 1520 Scepter of Judah (Sheveret Yehudah) was a notable chronicle of Jewish persecutions, written in Italy and published in the Ottoman Empire in 1550.[61][62][63][64][65] It is a transition between the medieval and modern period of Jewish history.[66][67] Born in Spain, Verga's views were shaped by the expulsion in 1492.[68][69] The historic work of astronomer Abraham Zacuto (1452-1515),[70][71] Sefer ha-Yuḥasin (1504), and Italian talmudic chronologer Gedaliah ibn Yahya ben Joseph (1515-1587), Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah (Chain of Tradition) (1587) were also of signifcance during this period.[72][29]

ha-Cohen

Joseph ha-Cohen (1496-1575) was a Sephardic physician and chronicler who is considered one of the most significant 16th century Jewish historians and Renaissance scholars.[73][74][75] Born in Avignon to Castilian and Aragonian Jewish parents and later in Genoa, he was cited and highly regarded by later historians such as Basnage.[76][77][78] His Emek Ha-Bakha (Vale of Tears), appeared in 1558[79] and is considered an important historical work.[29] The name comes from Psalm 84, and it is a history of Jewish martyrdom.[80] It consisted of the narrative of Jewish persecution that extracted from and built on the Jewish part of his earlier world histories, and inspired Salo Baron's idea of the "lachrymose" conception of Jewish history.[52] Yerushalmi notes that it begins in the post-biblical era.[29] Robert Bonfil notes that ha-Cohen's historiography is specifically shaped by the Jewish expulsion from Spain and France that ha-Cohen personally experienced.[52] ha-Cohen's sources included Samuel Usque.[81] He was a contemporary of the Italian-Jewish geographer Abraham Farissol and drew upon his work.[82]

De Rossi

Azariah dei Rossi (1511-1578) was an Italian-Jewish physician, rabbi, and a leading Torah scholar during the Italian Renaissance. Born in Mantua, he translated classical works such as Aristotle, and was known to quote Roman and Greek writers along with Hebrew in his work.[83][84][85] He was the first major author in Jewish historiography to incorporate and edit non-Jewish texts into his work.[53] His 1573 work Me'or Einayim (Light of the Eyes) is an important early work of humanistic 16th century Jewish historiography.[86][29][87][88][52][89] Bonfil writes that it was an attempt at a "New History" of the Jews and a work of ecclesiastical historiography, that adopted as its main tool, logical and philological criticism.[8] De Rossi's work was critical of the rabbinical establishment, questioning the historicity of post-biblical Jewish legends, and was met with condemnation, opprobrium and bans; Joseph Caro called for it to be burned.[90][91][92][93][94] Rossi's work mixed the world of secular Renaissance scholarship with Jewish rabbinical textual analysis, addressing contradictions, which offended the sensibilities of religious leaders such as the Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague, known as the Maharal, who said the words of Torah should not mix with those of science.[95] Nonetheless, the rabbis of Mantua, Judah Moscato and David Provençal, although critical in some ways, still considered him a respectable Jew with great value.[87] His work is considered by some to be an early example of the construction of Jewish identity through modern historical methods.[96]

Gans

David Gans (1541–1613) was a German-Jewish rabbi, astronomer, historian, and chronicler whose comprehensive historical work Tzemach David (1592) was a pioneering study of Jewish history.[98][99][100][101] Gans wrote on a variety of liberal arts and scientific topics, making him unique among the Ashkenazi for his production of secular scholarship.[102] Gans was a student of the Maharal, whom Yerushalmi says had the more profound ideas about Jewish history,[29] and of Moses Isserles.[95] Gans also corresponded with secular astronomers such as Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe, and drew on August Spangenberg.[103] Gans took inspiration from Josippon and Maimonides.[104] Gans' work is a hybrid of two parallel stories of world and Jewish history.[52][105] While not as cutting-edge a historian as his contemporary, de Rossi, his books introduced historiography to the Ashkenazi audience, making him a forerunner of subsequent developments in Jewish culture.[94]

17th century

- Yair Bacharach (1699)

Hannover

Nathan ben Moses Hannover's Yeven Mezulah (Abyss of Despair) (1653)[106][107][108][109][110][111] is a chronicle of the Khmelnytsky massacres or pogroms in eastern Europe in the mid 17th century. While a massacre certainly occurred, accounts and casualty numbers differ among Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish historians.[112][113] All three groups also use the story as part of their own national ideologies.[114]

Basnage

Jacques Basnage (1653-1723), a Huguenot living in the Netherlands, was one of the first authors in the modern era to publish a comprehensive post-biblical history of the Jews.[115] Basnage aimed to recount the story of the Jewish religion in his work Histoire des juifs, depuis Jésus-Christ jusqu'a present. Pour servir de continuation à l'histoire de Joseph (1706, in 15 volumes). Basnage heavily cites early modern and medieval Sephardic Jewish historians, such as Isaac Cardoso, Leon Modena, Abraham ibn Daud, Josippon, and Joseph ha-Cohen (whom he called "the best historian this nation has had since Josephus"), but also drew on Christian sources such as Jesuit Juan de Mariana.[76]

It was said to be the first comprehensive post-biblical history of Judaism and became the authoritative work for 100 years;[116] Basnage was aware that no such work had ever been published before.[117] Basnage sought to provide an objective account of the history of Judaism.[118][119] His work was widely influential, and developed further by other authors such as Hannah Adams.[120][121] Basnage's work is considered the birth of the "Christian historiography" of Jewish history.[76]

18th century

In the 18th century, reformists such as Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) invoked Maimonides to pursue a rational empancipationist movement for German Jews.[122][123] Mendelssohn has a significant role in Jewish history and the Haskalah or Jewish enlightenment. One of Mendelssohn's central goals concerned a grounding in Jewish history.[124] Isaac Euchel (1756-1804)'s Toledot Rabbenu Moshe ben Menahem (1788) was the first biography of Mendelssohn and significant in beginning a movement of biographical studies in Jewish historiography.[125][126] Meyer notes that Euchel acknowledges that Mendelssohn began his secular studies in history.[127] Israel Zamosz, one of Mendelssohn's teachers, also published a work applying reason and science to the statements of talmudic authorities.[128][129]

According to David B. Ruderman, the maskilim were inspired by such medieval and early modern historians and thinkers as Judah Messer Leon, de Rossi, ibn Verga, Moscato, Abraham Portaleone, Tobias Cohen, Simone Luzzatto, Menasseh ben Israel, and Isaac Orobio de Castro. Rossi's Me'or Einayim was republished by Isaac Satanow in 1794.[130]

The travel diary of Chaim Yosef David Azulai (1724-1806) is one important source for information on the broader Jewish world during this period.[131][132] The Vilna Gaon was another figure that encouraged critical reading of text and scientific study during this period.[133]

There was also significant progression in Yiddish historiography during the 18th century such as the work of Menahem Amelander in the Netherlands, who translated Josippon.[53][134][135][136][137][32][138][139] He also drew on Basnage.[140] His 1743 work Sheyris Yisroel (Remnant of Israel) picks up where Josippon left off.[135]Max Erik and Israel Zinberg considered it the foremost representative of its genre.[141] This was cited by Abraham Trebitsch with his Qorot ha-'Ittim and Abraham Chaim Braatbard with his Ayn Naye Kornayk.[50]

The Lithuanian rabbi Jehiel ben Solomon Heilprin (1660-1746)'s Seder HaDoroth (1768) was another 18th century historical work which cited the earlier work by Gans, ibn Yahya and Zacuto as well as other medieval work such as the itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela.[142][143][144]

19th century and birth of modern Jewish studies

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi wrote that first modern professional Jewish historians appeared in the early 19th century.[145] He wrote that "[v]irtually all nineteenth-century Jewish ideologies, from Reform to Zionism, would feel a need to appeal to history for validation".[146]

The German Wissenschaft des Judentums (or the "science of Judaism" or "Jewish studies") movement, was founded by Isaac Marcus Jost, Leopold Zunz, Heinrich Heine, Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport, and Eduard Gans, and was the birth of modern academic Jewish studies. Although considered a rationalist movement, it also drew on spiritual sources such as Yehuda Halevi's Kuzari.[147] Abraham Geiger founded the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums or school/seminary for Jewish studies, in Berlin in 1872, which remained until it was shuttered by the Nazis in 1942. Solomon Schechter was an important American Jewish student of the school.

During this period, most such study focused on pre-modern Jewish histories. Significant studies included Moritz Steinschneider (1816-1907)'s essay, "Geschichtsliteratur der Juden."

Théodore Reinach (1860-1928)'s Histoire des Israelites (1884) is the most significant example of 19th-century French-Jewish historiography which is something of a counterpoint to the mainstream German development in this time.[148] Marco Mortara (1815-1894) can be considered an Italian-Jewish version.[149] Isidore Loeb (1839-1892) founded the Revue des Études Juives or Jewish studies review, in 1880 in Paris. British Jews Claude Montefiore and Israel Abrahams founded The Jewish Quarterly Review, an English counterpart, in 1889.

Jost

Isaak Markus Jost (1793-1860) was the first Jewish author to publish a comprehensive post-biblical modern history of the Jews.[150] His Geschichte der Israeliten seit den Zeit der Maccabaer, in 9 volumes (1820–1829), was the first comprehensive history of Judaism from Biblical to modern times by a Jewish author. It primarily focused on recounting the history of the Jewish religion.[151]

Jost's history left "the differences among various phases of the Jewish past clearly apparent". He was criticized for this by later scholars such as Graetz, who worked to create an unbroken narrative.[152]

Zunz

Leopold Zunz (1794-1886), a colleague of Jost, was considered the father of academic Jewish studies in universities,or Wissenschaft des Judentums (or the "science of Judaism").[153] Zunz' article Etwas über die rabbinische Litteratur ("On Rabbinical Literature"), published in 1818, was a manifesto for modern Jewish scholarship.[92] Zunz was influenced by Rossi's philological and comparative linguistics approach.[133]

Zunz urged his contemporaries to, through the embrace of study of a wide swath of literature, grasp the geist or "spirit" of the Jewish people.[154] Zunz proposed an ambitious Jewish historiography and further proposed that Jewish people adopt history as a way of life.[92] Zunz not only proposed a university vision of Jewish studies, but believed Jewish history to be an inseparable part of human culture.[155] Zunz's historiographical view aligns with the "lachrymose" view of Jewish history of persecution.[156]

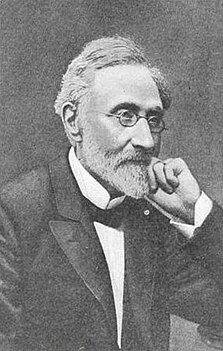

Graetz

Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891) was one of the first modern historians to write a comprehensive history of the Jewish people from a specifically Jewish perspective.[157][158] Geschichte der Juden (History of the Jews) (1853-1876) had a dual focus. While he provided a comprehensive history of the Jewish religion, he also highlighted the emergence of a Jewish national identity and the role of Jews in modern nation-states.[159][160] Graetz sought to improve on Jost's work, which he disdained for lacking warmth and passion.[161]

Salo Baron later identified Graetz with the "lachrymose conception" of Jewish history which he sought to critique.[162]

Baruch Ben-Jacob (1886-1943) likewise criticized Graetz' "sad and bitter" narrative for omitting Ottoman Jews.[148]

20th century histories

The 20th century saw the Shoah and the establishment of Israel, both of which had a major impact on Jewish historiography. Ephraim Deinard (1846–1930) was a notable 20th century historian of American Jews.

Dubnow

Simon Dubnow (1860-1941) wrote Weltgeschichte des Jüdischen Volkes (World History of the Jewish People), which focused on the history of Jewish communities across the world. His scholarship developed a unified Jewish national narrative, especially in the context of the Russian Revolution and Zionism.[163] Dubnow's work nationalized and secularized Jewish history, whilst also moving its modern center of gravity from Germany to Eastern Europe and shifting its focus from intellectual history to social history.[164] Michael Brenner commented that Yerushalmi's "faith of fallen Jews" observation "is probably applicable to no one more than to Dubnow, who claimed to be praying in the temple of history that he himself erected."[165]

Dinur

Ben-Zion Dinur (1884 – 1973) followed Dubnow with a Zionist version of Jewish history. Conforti writes that Dinur "provided Jewish historiography with a clear Zionist-nationalist structure... [and] established the Palestine-centric approach, which viewed the entire Jewish past through the prism of Eretz Israel".[166]

Baron

Salo Wittmayer Baron (1895-1989), a professor at Columbia University, became the first chair in Jewish history at a secular university in 1930.[145] He wrote A Social and Religious History of the Jews (18 vols., 2d ed. 1952–1983) covered both the religious and social aspects of Jewish history. His work is the most recent comprehensive multi-volume Jewish history.[167] His work further developed the Jewish national history, particularly in the wake of the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel.[168] Baron called for Jews and Jewish historical studies to be integrated into traditional general world history as a key part.[169][170]

Baer

Yitzhak Baer (1888-1980) made a significant contribution to medieval and modern Jewish historiography. He had a critique of Baron's view that had failed to take into account his friend Gershom Sholem's studies of Jewish mysticism and Jewish messianism. Baer aligned his approach with Israeli Zionist historians such as Dinur and Hayim Hillel Ben-Sasson.[171]

Later 20th century: history of historiography

Jewish historiography also developed uniquely in Jewish diaspora communities[172][173] such as Anglo-Jewish historiography,[174] Polish-Jewish historiography,[175] and American-Jewish historiography.[176]

Beginning around 1970, a new Polish-Jewish historiography gradually arose, driven by reprints of works by Zinberg, Dubnow, and Baron, as well as new consideration by Bernard Dov Weinryb. Relevant authors in Polish-Jewish historiography are Meier Balaban, Yitzhak Schipper and Moses Schorr.[177][178]

The concept of microhistory has also arisen to describe a new movement in Jewish history led by Francesca Trivellato and Carlo Ginzburg.[179] Yerushalmi is also described by his student Marina Rustow as practicing microhistory, that he didn't believe in traditional methods, "heritage," "contributions," but sought a spirituality and "immanence" in his study of history.[13]

Yerushalmi

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi (1932-2009) wrote Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory (1982) which explored the intersection of historical scholarship and Jewish collective memory. It has been described as the "pathbreaking study on the relationship between Jewish historiography and memory from the biblical period to the modern age".[180] He was influenced by his teacher, Salo Baron, and saw himself as a social historian of Jews, not of Judaism.[181] Whilst it largely centered on premodern Jewish histories, it set the stage for future analysis of modern Jewish histories.[182] Yerushalmi's history also focused on German Jewish, not Eastern European Jewish social history.[183] Yerushalmi wrote that:

...the secularization of Jewish history is a break with the past, [and] the historicizing of Judaism itself has been an equally significant departure... Only in the modern era do we really find, for the first time, a Jewish historiography divorced from Jewish collective memory and, in crucial respects, thoroughly at odds with it. To a large extent, of course, this reflects a universal and ever-growing modern dichotomy... Intrinsically, modern Jewish historiography cannot replace an eroded group memory which, as we have seen throughout, never depended on historians in the first place. The collective memories of the Jewish people were a function of the shared faith, cohesiveness, and will of the group itself, transmitting and recreating its past through an entire complex of interlocking social and religious institutions that functioned organically to achieve this. The decline of Jewish collective memory in modern times is only a symptom of the unraveling of that common network of belief and praxis through whose mechanisms, some of which we have examined, the past was once made present. Therein lies the root of the malady. Ultimately Jewish memory cannot be "healed" unless the group itself finds healing, unless its wholeness is restored or rejuvenated. But for the wounds inflicted upon Jewish life by the disintegrative blows of the last two hundred years the historian seems at best a pathologist, hardly a physician.[184]

Some scholars such as Bonfil, David N. Myers, and Amos Funkenstein took issue with Yerushalmi's interpretation of the importance of Jewish historiography or its relative abundance in the medieval period.[185][186] Gavriel D. Rosenfeld writes that Yerushalmi's fear that history would overtake memory was unfounded.[187] Yerushalmi also deeply studied the Sephardim, such as Isaac Cardoso. He was frustrated by "antiquarianism." He had a complex relationship with the Jerusalem school of historians including Baer, whom he disagreed with, but was influenced by, and Scholem. He was also influenced by Lucien Febvre. His student, Marina Rustow, writes that Yerushalmi, like his teacher Baron, believed modernity to be a trade-off and that the role of the Church in protecting, as well as persecuting, the Jewish people of premodern Europe was "anti-lachrymose," and drew admiration from his teacher. However she writes that he agreed with Baer and Scholem that history could be only understood in Jewish terms, and disagreed with Baron's more integrationist view. Ultimately, he is criticized for accepting the sources of the Spanish Inquisition without characterizing their motive as anti-Jewish.[13]

Meyer

Michael A. Meyer's "Ideas of Jewish History" (1974) is a milestone in the study of modern Jewish histories, and Meyer's ideas were developed further by Ismar Schorsch's "From Text to Context" (1994). These works emphasized the transformation of Jewish historical understanding in the modern era and are significant in summarizing the evolution of modern Jewish histories. According to Michael Brenner, these works – like Yerushalmi's before them – underlined the "break between a traditional Jewish understanding of history and its modern transformation".[188]

Brenner

Michael Brenner's Prophets of the Past, first published in German in 2006, was described by Michael A. Meyer as "the first broadly conceived history of modern Jewish historiography".[189]

References

- ^ Nemoy, Leon (1929). "The Yiddish Yosippon of 1546 in the Alexander Kohut Memorial Collection of Judaica". The Yale University Library Gazette. 4 (2): 36–39. ISSN 0044-0175. JSTOR 40856706.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 15: "Along with periodization we can also see the differing titles of works on Jewish history that cover more than one era as indexes of their respective orientations. It is no accident that Jost’s work on the history of religion is called The History of the Israelites; that Graetz titles his already nationally oriented work History of the Jews; that Dubnow, as a convinced diasporic nationalist, chooses the title World History of the Jewish People, in which both the national character of the Jews and their dispersal over the whole world are contained; and that in his monumental work Dinur distinguishes between Israel in Its Own Land and Israel in Dispersal. In all these cases the title is already a program."

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 49, 50: "At the same time, however, they shaped a scholarly discipline that used the weapons of historiography to elaborate new Jewish identities. All over Europe, during the nineteenth century historiography was part of the battle among Jews for their emancipation, their identification with their respective nation-states, and their striving for religious reform. What for Jews had earlier been one Jewish history was now transformed by historians into several Jewish histories in the respective national contexts.At the same time, during the second half of the nineteenth century a new variant of Jewish historiography developed that put passionate emphasis on the existence of a unified Jewish national history. Its begin- nings are found in the work of the most important Jewish historian of the nineteenth century, Heinrich Graetz."

- ^ Meyer 2007, p. 661: "A constant temptation within Jewish historiography has been and is still today its instrumentalization, whether for the sake of emancipation, religious reform, a socialist or Zionist ideology, or the resuscitation and reshaping of Jewish memory for the sake of Jewish survival - all of these standing against the Rankean ideal of historical writing for its own sake."

- ^ Yerushalmi 1982, p. 85: "It should be manifest by now that it did not derive from prior Jewish historical writing or historical thought. Nor was it the fruit of a gradual and organic evolution, as was the case with general modern historiography whose roots extend back to the Renaissance. Modern Jewish historiography began precipitously out of that assimilation from without and collapse from within which characterized the sudden emergence of Jews out of the ghetto. It originated, not as scholarly curiosity, but as ideology, one of a gamut of responses to the crisis of Jewish emancipation and the struggle to attain it."

- ^ Biale 1994, p. 3: "The question of Jewish politics lies at the very heart of any attempt to understand Jewish history. The dialectic between power and powerlessness that threads its way from biblical to modern times is one of the central themes in the long history of the Jews and, especially in the modern period, defines one of the key ideological issues in Jewish life. How one understands the history of Jewish politics may well determine the stance one takes on the possibility of Jewish existence in diaspora or the necessity for a Jewish state. Or conversely, perhaps the ideological position one takes on this political question may determine how one interprets Jewish history. It may therefore not be an exaggeration to say that modern Jewish historiography is the historiography of Jewish politics, even when its explicit concerns appear to lie elsewhere. Since the modern historian writes in a context in which political questions are so important, he or she brings them to bear--consciously or not--on the broad field of Jewish history. To take but one famous example, Gershom Scholem's magisterial history of Jewish mysticism cannot be separated from his commitment to Zionism, although in no sense can one speak of a crudely direct correspondence between the one and the other."

- ^ Meyer 2007, p. 662.

- ^ a b Bonfil, Robert (1997). "Jewish Attitudes toward History and Historical Writing in Pre-Modern Times". Jewish History. 11 (1): 7–40. doi:10.1007/BF02335351. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101283. S2CID 161957265.

- ^ Berger, David (2011), "Judaism and General Culture in Medieval and Early Modern Times", Cultures in Collision and Conversation, Essays in the Intellectual History of the Jews, Academic Studies Press, pp. 21–116, doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4xrd.5, ISBN 978-1-936235-24-7, JSTOR j.ctt21h4xrd.5, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Schwartz, Daniel B. (2015-06-30), 1. Our Rabbi Baruch: Spinoza and Radical Jewish Enlightenment, University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 25–47, doi:10.9783/9780812291513-003, ISBN 978-0-8122-9151-3, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Wertheim, David J. (2006). "Spinoza's Eyes: The Ideological Motives of German-Jewish Spinoza scholarship". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 13 (3): 234–246. doi:10.1628/094457006778994786. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 40753405.

- ^ Idel, Moshe (2007). "Yosef H. Yerushalmi's "Zakhor": Some Observations". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97 (4): 491–501. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 25470222.

- ^ a b c d Rustow, Marina (2014). "Yerushalmi and the Conversos". Jewish History. 28 (1): 11–49. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9198-x. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709808. S2CID 254599514.

- ^ Bod, Rens (2015), van Kalmthout, Ton; Zuidervaart, Huib (eds.), "The Importance of the History of Philology, or the Unprecedented Impact of the Study of Texts", The Practice of Philology in the Nineteenth-Century Netherlands, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 17–36, ISBN 978-90-8964-591-3, JSTOR j.ctt130h8j8.4, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Lambe, Patrick J. (1985). "Biblical Criticism and Censorship in Ancien Régime France: The Case of Richard Simon". The Harvard Theological Review. 78 (1/2): 149–177. doi:10.1017/S0017816000027425. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1509597. S2CID 162945310.

- ^ Vehlow, Katja (2021), Lieberman, Phillip I. (ed.), "Historiography", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 5: Jews in the Medieval Islamic World, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 5, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 974–992, doi:10.1017/9781139048873.037, ISBN 978-0-521-51717-1, retrieved 2023-11-08

- ^ גפני, ישעיהו; Gafni, Isaiah (1987). "On the Talmudic Chronology in "Iggeret Rav Sherira Gaon" / לחקר הכרונולוגיה התלמודית באיגרת רב שרירא גאון". Zion / ציון. נב (א): 1–24. ISSN 0044-4758. JSTOR 23559516.

- ^ גפני, ישעיהו; Gafni, Isaiah M. (2008). "On Talmudic Historiography in the Epistle of Rav Sherira Gaon: Between Tradition and Creativity / ההיסטוריוגרפיה התלמודית באיגרת רב שרירא גאון: בין מסורת ליצירה". Zion / ציון. עג (ג): 271–296. ISSN 0044-4758. JSTOR 23568181.

- ^ Gross, Simcha (2017). "When the Jews Greeted Ali: Sherira Gaon's Epistle in Light of Arabic and Syriac Historiography". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 24 (2): 122–144. doi:10.1628/094457017X14909690198980. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 44861517.

- ^ Kraemer, Joel L. (1971). Cohen, Gerson D. (ed.). "A Critical Edition with a Translation and Notes of the Book of Tradition". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 62 (1): 61–71. doi:10.2307/1453863. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1453863.

- ^ Halivni, David Weiss (1996). "Reflections on Classical Jewish Hermeneutics". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 62: 21–127. doi:10.2307/3622592. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622592.

- ^ Chazan, Robert (1994). "The Timebound and the Timeless: Medieval Jewish Narration of Events". History and Memory. 6 (1): 5–34. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 25618660.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1990). "The Babylonian Yeshivot and the Maghrib in the Early Middle Ages". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 57: 69–120. doi:10.2307/3622655. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622655.

- ^ Marcus, Ivan G. (1990). "History, Story and Collective Memory: Narrativity in Early Ashkenazic Culture". Prooftexts. 10 (3): 365–388. ISSN 0272-9601. JSTOR 20689283.

- ^ Marcus, Ralph (1948). "A 16TH CENTURY HEBREW CRITIQUE OF PHILO (Azariah dei Rossi's "Meor Eynayim", Pt. I, cc. 3–6)". Hebrew Union College Annual. 21: 29–71. ISSN 0360-9049. JSTOR 23503688.

- ^ Dönitz, Saskia (2012-01-01), "Historiography Among Byzantine Jews: The Case Of Sefer Yosippon", Jews in Byzantium, Brill, pp. 951–968, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004203556.i-1010.171, ISBN 978-90-04-21644-0, retrieved 2023-10-29

- ^ Avioz, Michael (2019). "The Place of Josephus in Abravanel's Writings". Hebrew Studies. 60: 357–374. ISSN 0146-4094. JSTOR 26833120.

- ^ Bowman, Steven (2010). "Jewish Responses to Byzantine Polemics from the Ninth through the Eleventh Centuries". Shofar. 28 (3): 103–115. ISSN 0882-8539. JSTOR 10.5703/shofar.28.3.103.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim (1979). "Clio and the Jews: Reflections on Jewish Historiography in the Sixteenth Century". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 46/47: 607–638. doi:10.2307/3622374. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622374.

- ^ Neuman, Abraham A. (1952). "Josippon and the Apocrypha". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 43 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/1452910. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1452910.

- ^ Gertner, Haim (2007). "Epigonism and the Beginning of Orthodox Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century Eastern Europe". Studia Rosenthaliana. 40: 217–229. doi:10.2143/SR.40.0.2028846. ISSN 0039-3347. JSTOR 41482513.

- ^ a b Schatz, Andrea (2019). Josephus in modern Jewish culture. Studies in Jewish history and culture. Leiden Boston (N.Y.): Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-39308-0.

- ^ "Josippon". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Zeitlin, Solomon (1963). "Josippon". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 53 (4): 277–297. doi:10.2307/1453382. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1453382.

- ^ Dönitz, Saskia (2015-12-15), Chapman, Honora Howell; Rodgers, Zuleika (eds.), "Sefer Yosippon (Josippon)", A Companion to Josephus (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 382–389, doi:10.1002/9781118325162.ch25, ISBN 978-1-4443-3533-0, retrieved 2023-11-06

- ^ Goodman, Martin; Weinberg, Joanna (2016). "The Reception of Josephus in the Early Modern Period". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 23 (3): 167–171. doi:10.1007/s12138-016-0398-2. ISSN 1073-0508. JSTOR 45240038. S2CID 255509625.

- ^ Bowman, Steven (2021-11-02). "Plato and Aristotle in Hebrew Garb: Review of Dov Schwartz, Jewish Thought in Byzantium in the Late Middle Ages". Judaica. Neue Digitale Folge. 2. doi:10.36950/jndf.2r5. ISSN 2673-4273. S2CID 243950830.

- ^ a b Bowman, Steven (1995). "'Yosippon' and Jewish Nationalism". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 61: 23–51. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 4618850.

- ^ Eleazar, Gutwirth (2022). "Leo Grech/Yehudah Mosconi : Hebrew Historiography and Collectionism in the Fourteenth Century". Helmantica. 73 (207): 221–237.

- ^ Bland, Kalman (1986-01-01), "An Islamic Theory of Jewish History: The Case of Ibn Khaldun", Ibn Khaldun and Islamic Ideology, Brill, pp. 37–45, doi:10.1163/9789004474000_006, ISBN 978-90-04-47400-0, retrieved 2023-11-08

- ^ Fischel, Walter J. (1961). "Ibn Khaldūn's Use of Historical Sources". Studia Islamica (14): 109–119. doi:10.2307/1595187. ISSN 0585-5292. JSTOR 1595187.

- ^ Ilan, Nahem. "Josippon, Book of". De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.josipponbookof. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Sela, Shulamit (1991). Book of Josippon and its parallel versions in Arabic and Judaeo-Arabic (in Hebrew). Universiṭat Tel Aviv, ha-Ḥug le-Historyah shel ʻam Yiśraʼel.

- ^ Dönitz, Saskia (2013-01-01), "Josephus Torn to Pieces—Fragments of Sefer Yosippon in Genizat Germania", Books within Books, Brill, pp. 83–95, doi:10.1163/9789004258501_007, ISBN 978-90-04-25850-1, retrieved 2023-11-08

- ^ Vollandt, Ronny (2014-11-19). "Ancient Jewish Historiography in Arabic Garb: Sefer Josippon between Southern Italy and Coptic Cairo". Zutot. 11 (1): 70–80. doi:10.1163/18750214-12341264. ISSN 1571-7283.

- ^ "Bowman on Sela, 'Sefer Yosef ben Guryon ha-ʻArvi' | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Wolf, Lucien (1908). ""Josippon" in England". Transactions (Jewish Historical Society of England). 6: 277–288. ISSN 2047-2331. JSTOR 29777757.

- ^ Reiner, Jacob (1967). "The English Yosippon". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 58 (2): 126–142. doi:10.2307/1453342. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1453342.

- ^ Vehlow, Katja (2017). "Fascinated by Josephus: Early Modern Vernacular Readers and Ibn Daud's Twelfth-Century Hebrew Epitome of Josippon". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 48 (2): 413–435. ISSN 0361-0160. JSTOR 44816356.

- ^ a b Wallet, Bart (2007). "Ongoing History: The Successor Tradition in Early Modern Jewish Historiography". Studia Rosenthaliana. 40: 183–194. doi:10.2143/SR.40.0.2028843. ISSN 0039-3347. JSTOR 41482510.

- ^ Ray, Jonathan (2009). "Iberian Jewry between West and East: Jewish Settlement in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean". Mediterranean Studies. 18: 44–65. doi:10.2307/41163962. ISSN 1074-164X. JSTOR 41163962.

- ^ a b c d e Bonfil, Robert (1988). "How Golden was the Age of the Renaissance in Jewish Historiography?". History and Theory. 27 (4): 78–102. doi:10.2307/2504998. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2504998.

- ^ a b c Rutkowski, Anna (2010). "Between history and legend". PaRDeS : Zeitschrift der Vereinigung für Jüdische Studien e.V. (16): 50–56. ISSN 1614-6492.

- ^ Meyer 1988, p. 1-2.

- ^ Hyman, Paula E. (2005). "Recent Trends in European Jewish Historiography". The Journal of Modern History. 77 (2): 345–356. doi:10.1086/431818. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 10.1086/431818. S2CID 143801802.

- ^ Berger, David (2011), "Sephardic and Ashkenazic Messianism in the Middle Ages: An Assessment of the Historiographical Debate", Cultures in Collision and Conversation, Essays in the Intellectual History of the Jews, Academic Studies Press, pp. 289–311, doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4xrd.16, ISBN 978-1-936235-24-7, JSTOR j.ctt21h4xrd.16, retrieved 2023-11-04

- ^ Peters, Edward (1995). "Jewish History and Gentile Memory: The Expulsion of 1492". Jewish History. 9 (1): 9–34. doi:10.1007/BF01669187. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101210. S2CID 159523585.

- ^ Tropper, Amram (2004). "The Fate of Jewish Historiography after the Bible: A New Interpretation". History and Theory. 43 (2): 179–197. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2004.00274.x. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 3590703.

- ^ Bonfil, Robert (1992). "The "Book of the Honeycomb's Flow" by Judah Messer Leon: The Rhetorical Dimension of Jewish Humanism in Fifteenth-Century Italy". Jewish History. 6 (1/2): 21–33. doi:10.1007/BF01695207. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101117. S2CID 161950742.

- ^ Lesley, Arthur M.; Leon, Judah Messer (1983). "Nofet Zufim, on Hebrew Rhetoric". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 1 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1525/rh.1983.1.2.101. ISSN 0734-8584. JSTOR 10.1525/rh.1983.1.2.101.

- ^ Funkenstein, Amos (1989). "Collective Memory and Historical Consciousness". History and Memory. 1 (1): 5–26. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 25618571.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History [4 Volumes]: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1514. ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3.

- ^ Cohen, Jeremy (2017). A Historian in Exile: Solomon ibn Verga, "Shevet Yehudah," and the Jewish-Christian Encounter. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4858-6. JSTOR j.ctv2t4c2k.

- ^ "Ibn Verga, Solomon". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ "The "Shebet Yehudah" and sixteenth century historiography | Article RAMBI990004793790705171 | The National Library of Israel". www.nli.org.il. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ COHEN, JEREMY (2009), "The blood libel in Solomon ibn Verga's Shevet Yehudah", Jewish Blood, Routledge, pp. 128–147, doi:10.4324/9780203876404-13, ISBN 978-0-203-87640-4, retrieved 2023-11-05

- ^ Ruderman, Daṿid; Veltri, Giuseppe; Wolfenbütteler Arbeitskreis für Renaissanceforschung; Leopold-Zunz-Zentrum zur Erforschung des Europäischen Judentums; Herzog August Bibliothek, eds. (2004). Cultural intermediaries: Jewish intellectuals in early modern Italy. Jewish culture and contexts. Philadelphia, Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3779-5.

- ^ Cohen, Jeremy (2013). "Interreligious Debate and Literary Creativity: Solomon ibn Verga on the Disputation of Tortosa". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 20 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1628/094457013X13661210446274. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 24751814.

- ^ Wacks, David A. (2015). Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production Before and After 1492. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01572-3. JSTOR j.ctt16gzfs2.

- ^ Neuman, Abraham A. (1967). "The Paradoxes and Fate of a Jewish Medievalist". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 57: 398–408. doi:10.2307/1453505. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1453505.

- ^ "Zacuto, Abraham Ben Samuel". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ "Ibn Yaḥya (or Ibn Yihyah), Gedaliah ben Joseph | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (1975). "Printing in Venice: Before Gutenberg?". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 45 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1086/620401. ISSN 0024-2519. JSTOR 4306536. S2CID 170339874.

- ^ Cassen, Flora (2017). Marking the Jews in Renaissance Italy: politics, religion, and the power of symbols. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-17543-3.

- ^ David, Abraham (2013-01-01), "Joseph Ha-Cohen and His Negative Attitude Toward R. Meir Katzenellenbogen (Maharam Padova)", The Italia Judaica Jubilee Conference, Brill, pp. 59–68, doi:10.1163/9789004243323_007, ISBN 978-90-04-24332-3, retrieved 2023-11-03

- ^ a b c Price, David H. (2020). ""The Sincerity of Their Historians": Jacques Basnage and the Reception of Jewish History". Jewish Quarterly Review. 110 (2): 290–312. doi:10.1353/jqr.2020.0009. ISSN 1553-0604. S2CID 219454578.

- ^ Fox, Yaniv (2019). "Chronicling the Merovingians in Hebrew the Early Medieval Chapters of Yosef Ha-Kohen's Divrei Hayamim". Traditio. 74: 423–447. doi:10.1017/tdo.2019.5. ISSN 0362-1529. JSTOR 26846041. S2CID 210485218.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (1975). "The Ethnic Background of Columbus: Inferences from a Genoese-Jewish Source, 1553-1557". Revista de Historia de América (80): 147–164. ISSN 0034-8325. JSTOR 20139182.

- ^ Roth, Cecil (1928). "The Jews of Malta". Transactions (Jewish Historical Society of England). 12: 187–251. ISSN 2047-2331. JSTOR 29777798.

- ^ Friedlander, Albert H. (1980). "Bonhoeffer and Baeck: Theology after Auschwitz". European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe. 14 (1): 26–32. ISSN 0014-3006. JSTOR 41444295.

- ^ "Joseph ben Joshua ben Meïr Ha-Kohen". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ^ Israel Zinberg (1974). A History of Jewish Literature: Italian Jewry in the Renaissance era. Cincinnati, Ohio: Hebrew Union College Press. ISBN 978-0-87068-240-7.

- ^ Miller, Peter N. (2007). "Lost and Found". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97 (4): 502–507. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 25470223.

- ^ Shulṿas, Mosheh Avigdor (1973). The Jews in the world of the Renaissance. Leiden: Brill [u.a.] ISBN 978-90-04-03646-8.

- ^ Shulvass, Moses A. (1948). "The Knowledge of Antiquity among the Italian Jews of the Renaissance". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 18: 291–299. doi:10.2307/3622202. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622202.

- ^ Malkiel, David (2013). "The Artifact and Humanism in Medieval Jewish Thought". Jewish History. 27 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1007/s10835-012-9169-z. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709729. S2CID 254594796.

- ^ a b Weinberg, Joanna (1978). "Azariah Dei Rossi: Towards a Reappraisal of the Last Years of His Life". Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia. 8 (2): 493–511. ISSN 0392-095X. JSTOR 24304990.

- ^ Veltri, G. (2009-01-01), "Chapter Four. Conceptions Of History: Azariah De' Rossi", Renaissance Philosophy in Jewish Garb, Brill, pp. 73–96, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004171961.i-278.17, ISBN 978-90-474-2528-1, retrieved 2023-10-29

- ^ Jacobs, Martin (2002). "Azariah de' Rossi: The Light of the Eyes (review)". Jewish Quarterly Review. 93 (1–2): 299–302. doi:10.1353/jqr.2002.0032. ISSN 1553-0604. S2CID 161927612.

- ^ "Rediscovering Azariah Dei Rossi". The Jerusalem Post. 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Baron, Salo Wittmayer (1929). "La méthode historique d'Azaria de Rossi (fin)". Revue des études juives. 87 (173): 43–78. doi:10.3406/rjuiv.1929.5623. S2CID 263187065.

- ^ a b c Wieseltier, Leon (1981). "Etwas Über Die Judische Historik: Leopold Zunz and the Inception of Modern Jewish Historiography". History and Theory. 20 (2): 135–149. doi:10.2307/2504764. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2504764.

- ^ Whitfield, S. J. (2002-10-01). "Where They Burn Books ..." Modern Judaism. 22 (3): 213–233. doi:10.1093/mj/22.3.213. ISSN 0276-1114.

- ^ a b Visi, Tamás (2014), "Gans, David: Born: 1541, Lippstadt Died: 1613, Prague", in Sgarbi, Marco (ed.), Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–4, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-02848-4_46-1, ISBN 978-3-319-02848-4, retrieved 2023-11-05

- ^ a b Ruderman, David B. (2001). Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2931-3.

- ^ Rosenberg-Wohl, David Michael (2014). Reconstructing Jewish Identity on the Foundations of Hellenistic History: Azariah de' Rossi's Me'or 'Enayim in Late 16th Century Northern Italy (Thesis). UC Berkeley.

- ^ a b Spicer, Joaneath (1996). "The Star of David and Jewish Culture in Prague around 1600, Reflected in Drawings of Roelandt Savery and Paulus van Vianen". The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery. 54: 203–224. ISSN 0083-7156. JSTOR 20169118.

- ^ Breuer, Mordechai; Graetz, Michael (1996). Deutsch-jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit. 1: Tradition und Aufklärung / von Mordechai Breuer u. Michael Graetz. München: Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-39702-8.

- ^ David, Abraham (2003). "The Lutheran Reformation in Sixteenth-Century Jewish Historiography". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 10 (2): 124–139. doi:10.1628/0944570033029167. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 40753327.

- ^ גרטנר, חיים; Gertner, Haim (2002). "The Beginning of 'Orthodox Historiography' in Eastern Europe: a Reassessment / ראשיתה של כתיבה היסטורית אורתודוקסית במזרח אירופה: הערכה מחודשת". Zion / ציון. סז (ג): 293–336. ISSN 0044-4758. JSTOR 23564878.

- ^ Alter, George (2011). "Dossier: David Gans: A Renaissance Jewish Astronomer". Aleph. 11 (1): 61–114. doi:10.2979/aleph.2011.11.1.61. ISSN 1565-1525. JSTOR 10.2979/aleph.2011.11.1.61.

- ^ Efron, Noah J.; Fisch, Menachem (2001). "Astronomical Exegesis: An Early Modern Jewish Interpretation of the Heavens". Osiris. 16: 72–87. doi:10.1086/649339. ISSN 0369-7827. JSTOR 301980. S2CID 161329118.

- ^ "Gans, David ben Shelomoh". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ "The Tzemach David | Henry Abramson". henryabramson.com. 2016-02-11. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ Graetz, Heinrich. "History of the Jews, Vol. 4 (of 6)". Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ Voß, Rebekka (2023). Sons of Saviors: The Red Jews in Yiddish Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ שמרוק, חנא; Shmeruk, Chone (1988). "Yiddish Literature and 'Collective Memory': The Case of the Chmielnitski Massacres / גזירות ת"ח ות"ט: ספרות יידיש וזיכרון קולקטיבי". Zion / ציון. נג (ד): 371–384. ISSN 0044-4758.

- ^ "HANNOVER, NATHAN (NATA) BEN MOSES - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ "YIVO | Hannover, Natan Note". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ Bacon, Gershon (2003). ""The House of Hannover": Gezeirot Tah in Modern Jewish Historical Writing". Jewish History. 17 (2): 179–206. ISSN 0334-701X.

- ^ Stampfer, Shaul (2003). "What Actually Happened to the Jews of Ukraine in 1648?". Jewish History. 17 (2): 207–227. ISSN 0334-701X.

- ^ Stow, Kenneth; Teller, Adam (2003). "Introduction: The Chmielnitzky Massacres, 1648-1649: Jewish, Polish, and Ukrainian Perspectives". Jewish History. 17 (2): 105–106. ISSN 0334-701X.

- ^ Kohut, Zenon E. (2003). "The Khmelnytsky Uprising, the Image of Jews, and the Shaping of Ukrainian Historical Memory". Jewish History. 17 (2): 141–163. ISSN 0334-701X.

- ^ Yakovenko, Natalia (2003). "The Events of 1648-1649: Contemporary Reports and the Problem of Verification". Jewish History. 17 (2): 165–178. ISSN 0334-701X.

- ^ Meyer 1988, p. 169.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 8, 19.

- ^ Yerushalmi 1982, p. 81b: "It is significant that the first real attempt in modern times at a coherent and comprehensive post-biblical history of the Jews was made, not by a Jew, but by a French Huguenot minister and diplomat, Jacques Basnage, who had found refuge in Holland… nothing like it had been produced before, and Basnage knew this. "I dare to say," he writes, "that no historian has appeared among the Jews themselves who has gathered together so many facts concerning their nation." He complains of the paucity of reliable materials. Of those Jewish works that were devoted to the "chain of tradition" he observes that, "attached only to the succession of the persons through whom the tradition has passed from mouth to mouth, they have preserved the names and have often neglected the rest.""

- ^ de Beauval, J.B. (1716). Histoire des juifs, depuis Jésus-Christ jusqu'a present. Pour servir de continuation à l'histoire de Joseph. Par Mr. Basnage. Nouvelle edition augmentée (in French). chez Henri Scheurleer. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Segal, Lester A. (1983). "Jacques Basnage de Beauval's". Hebrew Union College Annual. 54. Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion: 303–324. ISSN 0360-9049. JSTOR 23507671. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Meyer 1988, p. 169-172.

- ^ Arkush, Allan; Breuer, Edward (1999). "The Limits of Enlightenment: Jews, Germans, and the Eighteenth-Century Study of Scripture". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 89 (3/4): 393. doi:10.2307/1455033. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1455033.

- ^ Myers, David (1986). "The Scholem-Kurzweil Debate and Modern Jewish Historiography". Modern Judaism. 6 (3): 261–286. doi:10.1093/mj/6.3.261. ISSN 0276-1114. JSTOR 1396217.

- ^ Sacks, Elias Reinhold (2012). "Enacting a "Living Script": Moses Mendelssohn on History, Practice, and Religion".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Barzilay, Isaac (1974). Altmann, Alexander (ed.). "Moses Mendelssohn: A Biographical Study by Alexander Altmann". Jewish Social Studies. 36 (3/4): 330–335. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4466842.

- ^ Sorkin, David (1994). "The Case for Comparison: Moses Mendelssohn and the Religious Enlightenment". Modern Judaism. 14 (2): 121–138. doi:10.1093/mj/14.2.121. ISSN 0276-1114. JSTOR 1396291.

- ^ Meyer 1988.

- ^ Sinkoff, Nancy (2020), "In the Podolian Steppe", Out of the Shtetl, Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands, Brown Judaic Studies, pp. 14–49, doi:10.2307/j.ctvzpv5tn.10, ISBN 978-1-946527-96-7, JSTOR j.ctvzpv5tn.10, S2CID 242642210, retrieved 2023-11-06

- ^ "YIVO | Zamość, Yisra'el ben Mosheh ha-Levi". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Ruderman, David B. (2010-04-12). Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History. Princeton University Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-4008-3469-3.

- ^ Lehmann, Matthias B. (2007). ""Levantinos" and Other Jews: Reading H. Y. D. Azulai's Travel Diary". Jewish Social Studies. 13 (3): 1–34. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4467773.

- ^ Cohen, Julia Phillips; Stein, Sarah Abrevaya (2010). "Sephardic Scholarly Worlds: Toward a Novel Geography of Modern Jewish History". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 100 (3): 349–384. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 20750709.

- ^ a b Thulin, Mirjam; Krah, Markus; Meyer, Michael A.; Schorsch, Ismar; Brodt, Eliezer; Sariel, Eliezer; Yedidya, Asaf; Esther, Solomon; Kessler, Samuel J. (2018). Cultures of Wissenschaft des Judentums at 200. Universitätsverlag Potsdam. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-86956-440-1.

- ^ Fuks-Mansfeld, R.G. (1981). "Yiddish Historiography in the Time of the Dutch Republic". Studia Rosenthaliana. 15 (1): 9–19. ISSN 0039-3347. JSTOR 41481882.

- ^ a b Wallet, B. T. (2012). "Links in a chain: Early modern Yiddish historiography in the northern Netherlands (1743-1812)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Amelander (Amlander), Menahem Mann Ben Solomon Ha-Levi". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ "Amelander (also Amlander), Menahem Mann ben Solomon Ha-Levi | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Menahem Man ben Salomo Halevi und sein jiddisches Geschichtswerk "Sche'erit Jisrael" | מאמר RAMBI990003748120705171 | הספרייה הלאומית". www.nli.org.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "menahem man ben salomo halevi und sein jiddisches geschichtswerk "sche'erit jisrael"". De Gruyter (in German). Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Hidden Polemic: Josephus's Work in the Historical Writings of Jacques Basnage and Menaḥem Amelander". Josephus in Modern Jewish Culture: 42. 2019.

- ^ Smith, Mark L. (December 2021). "Two Views of Yiddish Culture in the Netherlands". Studia Rosenthaliana. 47 (2): 117–138. doi:10.5117/SR2021.2.002.SMIT (inactive 30 October 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2023 (link) - ^ "Heilprin, Jehiel ben Solomon | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Adler, M. N. (1905). "The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela (Continued)". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 18 (1): 84–101. doi:10.2307/1450823. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1450823.

- ^ "יחיאל בן שלמה הלפרין (1660 בערך-1746 בערך) | הספרייה הלאומית". www.nli.org.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ a b Yerushalmi 1982, p. 81a: "As a professional Jewish historian I am a new creature in Jewish history. My lineage does not extend beyond the second decade of the nineteenth century, which makes me, if not illegitimate, at least a parvenu within the long history of the Jews. It is not merely that I teach Jewish history at a university, though that is new enough. Such a position only goes back to 1930 when my own teacher, Salo Wittmayer Baron, received the Miller professorship at Columbia, the first chair in Jewish history at a secular university in the Western world."

- ^ Yerushalmi 1982, p. 86: "The modern effort to reconstruct the Jewish past begins at a time that witnesses a sharp break in the continuity of Jewish living and hence also an ever-growing decay of Jewish group memory. In this sense, if for no other, history becomes what it had never been before - the faith of fallen Jews. For the first time history, not a sacred text, becomes the arbiter of Judaism. Virtually all nineteenth-century Jewish ideologies, from Reform to Zionism, would feel a need to appeal to history for validation. Predictably, "history" yielded the most varied conclusions to the appellants."

- ^ Kohler, George Y. (2019). "Yehuda Halevi's Kuzari and the Wissenschaft des Judentums (1840–1865)". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 109 (3): 335–359. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 26900154.

- ^ a b Naar, Devin E. (2014). "Fashioning the "Mother of Israel": The Ottoman Jewish Historical Narrative and the Image of Jewish Salonica". Jewish History. 28 (3/4): 337–372. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9216-z. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709820. S2CID 254602444.

- ^ Salah, Asher (2019-07-22), The Intellectual Networks of Rabbi Marco Mortara (1815–1894): An Italian "Wissenschaftler des Judentums", De Gruyter, pp. 59–76, doi:10.1515/9783110554618-005, ISBN 978-3-11-055461-8, S2CID 200095670, retrieved 2023-11-06

- ^ Meyer 1988, p. 167.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 13, 32.

- ^ Meyer 1988, p. 175: "In fact, however, Jost did not tear a coherent fabric asunder. Rather he loosely stitched together sources that he found unconnected, leaving the differences among various phases of the Jewish past clearly apparent. Graetz declared that his own approach was entirely different: not accumulative but dialectical - and hence fully integrative… As historicism in Germany came increasingly to center upon the German legacy and to act as a force for German unity, so did Graetz come to view study of the Jewish past as a tool for reversing the declining salience of Jewish identity in a community by then well on the road to social, cultural, and political integration. It was this motive, carried further to national consciousness and divested of its close religious connection, which came to prominence in eastern Europe toward the end of the nineteenth century."

- ^ Veltri, Giuseppe (2000). "A Jewish Luther? The Academic Dreams of Leopold Zunz". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 7 (4): 338–351. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 40753273.

- ^ Bitzan, Amos (2017). "Leopold Zunz and the Meanings of Wissenschaft". Journal of the History of Ideas. 78 (2): 233–254. doi:10.1353/jhi.2017.0012. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 90002027. PMID 28366886. S2CID 27183205.

- ^ Berti, Silvia (1996). "A World Apart? Gershom Scholem and Contemporary Readings of 17th Century Jewish-Christian Relations". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 3 (3): 212–224. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 40753161.

- ^ Myers, David N. (1999). ""Mehabevin Et Ha-Tsarot": Crusade Memories and Modern Jewish Martyrologies". Jewish History. 13 (2): 49–64. doi:10.1007/BF02336580. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101376. S2CID 161793041.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 13, 15, 56-57, 73.

- ^ Singer, Saul Jay (2020-10-14). "The Jewish-Historical Philosophy Of Heinrich Graetz". Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 53-92.

- ^ Meyer, Michael A. (1986). "Heinrich Graetz and Heinrich Von Treitschke: A Comparison of Their Historical Images of the Modern Jew". Modern Judaism. 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1093/mj/6.1.1. ISSN 0276-1114. JSTOR 1396500.

- ^ Teller, Adam (2014). "Revisiting Baron's "Lachrymose Conception": The Meanings of Violence in Jewish History". AJS Review. 38 (2): 431–439. doi:10.1017/S036400941400035X. ISSN 0364-0094. S2CID 163063819.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 43-120.

- ^ Meyer 2007, p. 663.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 106: "Yerushalmi’s observation that history could become a religion for unbelieving Jews is probably applicable to..."

- ^ Conforti 2005, p. 2: "Zionist historiographers accepted and welcomed this view, especially historians like Ben Zion Dinur, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Yosef Klausner, Avraham Ya’ari and others. These historians acted out of secular and nationalist motivations.They based their study of Jewish history on the idea that history has a central role in creating a modern, secular-nationalist Jewish identity. History, from their point of view, provided an alternative to the religious ethics of traditional Jewish identity. This school of thought emphasized the ideological motif in a sometimes explicit manner. Although the leaders of this school were exceptionally talented historians, the ideological mission they adopted often resulted in the formulation of a Zionist-nationalist image of the course of all Jewish history. The best known example of this nationalist approach among researchers in Eretz Israel is Ben Zion Dinur (1884–1973). To a large extent, his historiographic opus parallels the work of other nationalist historians in Europe, as Arielle Rein has demonstrated in her doctoral dissertation (Rein). His energetic work laid the foundation for research of Jewish history in Eretz Israel. A close examination of his writings reveals that he provided Jewish historiography with a clear Zionist-nationalist structure: A. Dinur, along with Ben-Zvi (Ben-Zvi), established the Palestine-centric approach, which viewed the entire Jewish past through the prism of Eretz Israel."

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 123-131.

- ^ Kaplan, Debra; Teter, Magda (2009). "Out of the (Historiographie) Ghetto: European Jews and Reformation Narratives". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 40 (2): 365–394. ISSN 0361-0160. JSTOR 40540639.

- ^ Barzilay, Isaac E. (1994). "Yiṣḥaq (Fritz) Baer and Shalom (Salo Wittmayer) Baron: Two Contemporary Interpreters of Jewish History". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 60: 7–69. doi:10.2307/3622569. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622569.

- ^ Marcus, Ivan G. (2010). "Israeli Medieval Jewish Historiography: From Nationalist Positivism to New Cultural and Social Histories". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 17 (3): 244–285. doi:10.1628/094457010792912848. ISSN 0944-5706. JSTOR 20798279.

- ^ McCoskey, Denise Eileen (2003). "Diaspora in the Reading of Jewish History, Identity, and Difference". Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies. 12 (3): 387–418. doi:10.1353/dsp.2011.0012. ISSN 1911-1568. S2CID 145296196.

- ^ Endelman, Todd M. (1991). "The Legitimization of the Diaspora Experience in Recent Jewish Historiography". Modern Judaism. 11 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1093/mj/11.2.195. ISSN 0276-1114. JSTOR 1396267.

- ^ Gartner, Lloyd P. (1986). "A Quarter Century of Anglo-Jewish Historiography". Jewish Social Studies. 48 (2): 105–126. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4467326.

- ^ Friedman, Philip (1949). "Polish Jewish Historiography between the Two Wars (1918-1939)". Jewish Social Studies. 11 (4): 373–408. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4464843.

- ^ Handlin, Oscar (1976). "A Twenty Year Retrospect of American Jewish Historiography". American Jewish Historical Quarterly. 65 (4): 295–309. ISSN 0002-9068. JSTOR 23880299.

- ^ Rosman, Moshe (2018), Polonsky, Antony; Węgrzynek, Hanna; Żbikowski, Andrzej (eds.), "Polish–Jewish Historiography 1970–2015: Construction, Consensus, Controversy", New Directions in the History of the Jews in the Polish Lands, Academic Studies Press, pp. 60–77, doi:10.2307/j.ctv7xbrh4.12, JSTOR j.ctv7xbrh4.12, retrieved 2023-11-08

- ^ Rosman, M. J. (1987). Litman, Jacob (ed.). "Litman's "Contribution of Yitzhak Schipper"". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 78 (1/2): 151–153. doi:10.2307/1454096. ISSN 0021-6682.

- ^ katzcenterupenn. "The Case of Jewish History". Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ^ Brenner 2010, p. 221.

- ^ Dubin, Lois C. (2014). "Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, the Royal Alliance, and Jewish Political Theory". Jewish History. 28 (1): 51–81. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9199-9. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709809. S2CID 254597671.

- ^ Brenner 2006, p. 15: The first attempts to deal with the history of Jewish history writing were made by the scions of 19th-century Wissenschaft des Judentums, most notably Moritz Steinschneider in his essay on the Geschichtsliteratur der Juden which, however, like most of his writings was a bibliographical essay rather than a comprehensive historical analysis. Naturally, Steinschneider and his colleagues dealt mainly with premodern accounts of Jewish history, an emphasis that can also be found in more recent attempts to analyze Jewish historiography, such as Salo Baron's essays on the topic collected under the title History and Jewish Historians (1964) and the more recent Perceptions of Jewish History (1993) by the late Amos Funkenstein. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi's much acclaimed Zakhor (1989), which is not only the first comprehensive study but up to now the definitive systematic analysis of Jewish history writing, laid the groundwork for any contemporary discussion on Jewish history, but it does not focus on the history of modern Jewish history writing. After his profound discussion of premodern Jewish history and memory, Yerushalmi stresses the break and not the continuity in his concluding chapter on modern Jewish historical writing. Zakhor thus opens the way for a systematic discussion of modern Jewish historiography without undertaking such an attempt itself.

- ^ Efron, John M. (2014). "Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi: Historian of German Jewry". Jewish History. 28 (1): 83–95. doi:10.1007/s10835-014-9200-7. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 24709810. S2CID 254602762.

- ^ Yerushalmi 1982, p. 91-94.

- ^ Myers, David N.; Funkenstein, Amos (1992). "Remembering "Zakhor": A Super-Commentary [with Response]". History and Memory. 4 (2): 129–148. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 25618637.

- ^ Raz-Krakotzkin, Amnon (2007). "Jewish Memory between Exile and History". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97 (4): 530–543. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 25470226.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Gavriel D. (2007). "A Flawed Prophecy? "Zakhor", the Memory Boom, and the Holocaust". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97 (4): 508–520. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 25470224.

- ^ Brenner 2006, p. 15-16: The most comprehensive attempts so far to summarize the achievements of Wissenschaft des Judentums and modern Jewish historiography are a collection of essays and an anthology. Ismar Schorsch's From Text to Context (1994), which brings together the author's essays on modern Jewish scholarship, underlines the same break between a traditional Jewish understanding of history and its modern transformation that Yerushalmi stressed in Zakhor. This break is also made clear in the only systematic anthology of Jewish history writing, Michael Meyer's pioneering Ideas of Jewish History (1987). In his introduction, which remains the most compact treatment of the subject, Mever writes: "It was not until the nineteenth century that a reflective conception of Jewish history became central to the consciousness of the Jew. The reasons for this new concern lay first of all in a transformation of the cultural environment.”

- ^ Meyer 2007, p. 661a.

Bibliography

- Baron, Salo Wittmayer; Hertzberg, A.; Feldman, L.A. (1964). History and Jewish Historians: Essays and Addresses. Jewish Publication Society of America. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- Batnitzky, Leora (2011). How Judaism Became a Religion: An Introduction to Modern Jewish Thought. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13072-9. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- Biale, David (1994). "Modern Jewish Ideologies and the Historiography of Jewish Politics". In Frankel, Jonathan (ed.). Studies in Contemporary Jewry: X: Reshaping the Past: Jewish History and the Historians. OUP USA/Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ISBN 978-0-19-509355-1. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- Brenner, Michael (2006). The Same History is Not the Same Story: Jewish History and Jewish Politics (PDF). Dorit and Gerald Paul lecture. Robert and Sandra S. Borns Jewish Studies Program, Indiana University. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Brenner, Michael (2010). Prophets of the Past: Interpreters of Jewish History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3661-1.

- Conforti, Yitzhak (2005). "Alternative voices in Zionist historiography". Journal of Modern Jewish Studies. 4 (1). Informa UK Limited: 1–12. doi:10.1080/14725880500052667. ISSN 1472-5886. S2CID 144459744.

- Conforti, Yitzhak (2012). "Zionist Awareness of the Jewish Past: Inventing Tradition or Renewing the Ethnic Past?". Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism. 12 (1). Wiley: 155–171. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9469.2012.01155.x. ISSN 1473-8481.

- Feiner, S. (2004). Haskalah and History: The Emergence of a Modern Jewish Historical Consciousness. Littman Library Liverpool University Press Series. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. ISBN 978-1-904113-10-2. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- Funkenstein, Amos (1993). Perceptions of Jewish History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91219-9. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- Gareau, Paul L. (2011). "History as the Rise Of a Modern Jewish Identity". Revue de Sciences des Religions d'Ottawa // Ottawa Journal of Religion. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- Gechtman, Roni (2012-05-01). "Creating a Historical Narrative for a Spiritual Nation: Simon Dubnow and the Politics of the Jewish Past". Journal of the Canadian Historical Association. 22 (2). Consortium Erudit: 98–124. doi:10.7202/1008979ar. ISSN 1712-6274.

- Helled, Alon (2021). "The Israeli National Habitus and Historiography: The Importance of Generations and State-Building". Norbert Elias in Troubled Times. Palgrave Studies on Norbert Elias. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 295–311. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-74993-4_16. ISBN 978-3-030-74992-7. ISSN 2662-3102. S2CID 238937377.

- Israel, Jonathan I. (1998). European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism, 1550-1750 (Third ed.). The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. ISBN 1-874774-42-0.

- מיכאל, ראובן (Reuven Michael) (1993). הכתיבה ההיסטורית היהודית: מהרנסנס עד העת החדשה (in Hebrew). מוסד ביאליק. ISBN 978-965-342-601-6. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- מיכאל, ראובן (Reuven Michael) (1983). י״מ יוסט, אבי ההיסטוריוגרופיה היהודית המודרנית (in Hebrew). הוצאת ספרים ע״ש י״ל מאגנס, האוניברסיטה העבירת. ISBN 978-965-223-450-6. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- מיכאל, ראובן (Reuven Michael) (2003). היינריך גרץ: ההיסטוריון של העם היהודי (in Hebrew). מוסד ביאליק. ISBN 978-965-342-843-0. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- Meyer, Michael A. (1974). Ideas of Jewish History. Library of Jewish studies. Behrman House. ISBN 978-0-87441-202-4. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- Meyer, Michael A. (1988). "The Emergence of Jewish Historiography: Motives and Motifs". History and Theory. 27 (4). [Wesleyan University, Wiley]: 160–175. doi:10.2307/2505001. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2505001. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Meyer, Michael A. (2007). "New Reflections on Jewish Historiography". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 97 (4). [University of Pennsylvania Press, Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, University of Pennsylvania]: 660–672. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 25470231. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- Myers, David N. (1988). "History as Ideology: The Case of Ben Zion Dinur, Zionist Historian". Modern Judaism. 8 (2). Oxford University Press: 167–193. doi:10.1093/mj/8.2.167. ISSN 0276-1114. JSTOR 1396383. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- Myers, David N. (2018). The Stakes of History: On the Use and Abuse of Jewish History for Life. The Franz Rosenzweig Lecture Series. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-23140-3. Retrieved 2023-09-21.

- Myers, David N.; Kaye, Alexander (2013). The Faith of Fallen Jews: Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi and the Writing of Jewish History. Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry. Brandeis University Press. ISBN 978-1-61168-487-2. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- Ram, Uri (1995). "Zionist Historiography and the Invention of Modern Jewish Nationhood: The Case of Ben Zion Dinur". History and Memory. 7 (1). Indiana University Press: 91–124. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 25618681. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Rosman, Moshe (2007). How Jewish is Jewish History?. The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-909821-12-5.

- Ruderman, David B. (2010). Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14464-1.

- Sand, Shlomo (2020). The Invention of the Jewish People. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-78873-661-9. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- Schorsch, Ismar (1994). From Text to Context: The Turn to History in Modern Judaism. Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry Waltham, Mass.: The Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry series. Brandeis University Press. ISBN 978-0-87451-664-7. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- Schulin, Ernst [in German] (1995). 'The Most Historical of All Peoples': Nationalism and the New Construction of Jewish History in Nineteenth-century Germany (PDF). Annual Lecture - German Historical Institute London. German Historical Institute. ISBN 978-0-9521607-8-6. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- Steinschneider, Moritz (1905). Die geschichtsliteratur der Juden in druckwerken und handschriften, zusammengestellt: von Moritz Steinschneider (in German). H. Itzkowski. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim (1982). Zakhor, Jewish History and Jewish Memory. Samuel and Althea Stroum lectures in Jewish studies. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95939-9. Retrieved 2023-09-19.