Crass

Crass | |

|---|---|

Crass on stage in Cumbria in May 1984, with the slogan "there is no authority but yourself" in the background. From left to right: Pete Wright, Steve Ignorant, and N.A. Palmer. | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Epping, Essex, England |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1977–1984 |

| Labels | |

| Past members |

|

Crass were an English art collective and punk rock band formed in Epping, Essex in 1977,[1] who promoted anarchism as a political ideology, a way of life, and a resistance movement. Crass popularised the anarcho-punk movement of the punk subculture, advocating direct action, animal rights, feminism, anti-fascism, and environmentalism. The band used and advocated a DIY ethic in its albums, sound collages, leaflets, and films.

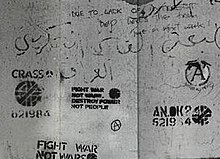

Crass spray-painted stencilled graffiti messages in the London Underground system and on advertising billboards, coordinated squats and organised political action. The band expressed its ideals by dressing in black, military-surplus-style clothing and using a stage backdrop amalgamating icons of perceived authority such as the Christian cross, the swastika, the Union Jack, and the ouroboros.

The band was critical of the punk subculture[2] and youth culture in general; nevertheless, the anarchist ideas that they promoted have maintained a presence in punk.[3] Due to their free experimentation and use of tape collages, graphics, spoken word releases, poetry, and improvisation, they have been associated with avant-punk[4][5][6] and art punk.[7]

History

1977: Origins

The band was based around an anarchist commune in a 16th-century cottage, Dial House, near Epping, Essex,[8] and formed when commune founder Penny Rimbaud began jamming with Steve Ignorant[9] (who was staying in the house at the time). Ignorant was inspired to form a band after seeing The Clash perform at Colston Hall in Bristol,[10] whilst Rimbaud, a veteran of avant garde performance art groups such as EXIT and Ceres Confusion,[11] was working on his book Reality Asylum. They produced "So What?" and "Do They Owe Us A Living?" as a drum-and-vocal duo.[12] They briefly called themselves Stormtrooper[13] before choosing Crass in reference to a line in the David Bowie song "Ziggy Stardust" ("The kids were just crass").[14]

Other friends and household members joined (including Gee Vaucher, Pete Wright, N. A. Palmer and Steve Herman), and Crass played their first live gig at a squatted street festival in Huntley Street, North London. They planned to play five songs, but a neighbour "pulled the plug" after three.[15] Guitarist Steve Herman left the band soon afterwards, and was replaced by Phil Clancey, a.k.a. Phil Free.[16] Joy De Vivre and Eve Libertine also joined around this time. Other early Crass performances included a four-date tour of New York City,[17] a festival gig in Covent Garden[18] and regular appearances with the U.K. Subs at The White Lion, Putney and Action Space in central London. The latter performances were often poorly attended: "The audience consisted mostly of us when the Subs played and the Subs when we played".[19]

Crass played two gigs at the Roxy Club in Covent Garden, London.[18] According to Rimbaud, the band arrived drunk at the second show and were ejected from the stage; this inspired their song "Banned from the Roxy",[20] and Rimbaud's essay for Crass' self-published magazine International Anthem, "Crass at the Roxy".[21] After the incident the band took themselves more seriously, avoiding alcohol and cannabis before shows and wearing black, military-surplus-style clothing on and offstage.[22]

They introduced their stage backdrop, a logo designed by Rimbaud's friend Dave King.[23] This gave the band a militaristic image, which led to accusations of fascism.[24] Crass countered that their uniform appearance was intended to be a statement against the "cult of personality", so (in contrast to many rock bands) no member would be identified as the "leader".[24]

Conceived and intended as cover artwork for a self-published pamphlet version of Rimbaud's Christ's Reality Asylum,[25] the Crass logo was an amalgam of several "icons of authority" including the Christian cross, the swastika, the Union Jack and a two-headed Ouroboros (symbolising the idea that power will eventually destroy itself).[26][27] Using such deliberately mixed messages was part of Crass' strategy of presenting themselves as a "barrage of contradictions",[28] challenging audiences to (in Rimbaud's words) "make your own fucking minds up".[29] This included using loud, aggressive music to promote a pacifist message,[30] a reference to their Dadaist, performance-art backgrounds and situationist ideas.[31]

The band eschewed elaborate stage lighting during live sets, preferring to play under 40-watt household light bulbs; the technical difficulties of filming under such lighting conditions partly explains why there is little live footage of Crass.[32] They pioneered multimedia presentation, using video technology (back-projected films and video collages by Mick Duffield and Gee Vaucher) to enhance their performances, and also distributed leaflets and handouts explaining anarchist ideas to their audiences.[33]

1978–1979: The Feeding of the 5000 and Crass Records

Crass' first release was The Feeding of the 5000 (an 18-track, 12" 45 rpm EP on the Small Wonder label) in 1978. Workers at an Irish record-pressing plant refused to handle it due to the allegedly blasphemous content of the song "Asylum",[34][35] and the record was released without it. In its place were two minutes of silence, entitled "The Sound of Free Speech". This incident prompted Crass to set up their own independent record label, Crass Records, to prevent Small Wonder from being placed in a compromising position and to retain editorial control over their material.[36]

A re-recorded, extended version of "Asylum", renamed "Reality Asylum", was shortly afterwards released on Crass Records as a 7" single and Crass were investigated by the police due to the song's lyrics. The band were interviewed at their Dial House home by Scotland Yard's vice squad, and threatened with prosecution; however, the case was dropped.[19] "Reality Asylum" retailed at 45p (when most other singles cost about 90p),[37] and was the first example of Crass' "pay no more than..." policy: issuing records as inexpensively as possible. The band failed to factor value added tax into their expenses, causing them to lose money on every copy sold.[38] A year later Crass Records released new pressings of The Feeding of the 5000 (subtitled "The Second Sitting"), restoring the original version of "Asylum".

1980: Stations of the Crass and Bloody Revolutions

In 1979 the band released their second album (Stations of the Crass), financed with a loan from Poison Girls,[39] a band with whom they regularly appeared. This was a double album, with three sides of new material and a fourth side recorded live at the Pied Bull in Islington.

The next Crass single, 1980's "Bloody Revolutions", was a benefit release with Poison Girls which raised £20,000 to fund the Wapping Autonomy Centre.[23] The words were a critique (from an anarchist-pacifist perspective) of the traditional Marxist view of revolutionary struggle, and were (in part) a response to violence marring a gig at Conway Hall in London's Red Lion Square at which both bands performed in September 1979.[40] The show was intended as a benefit for the so-called "Persons Unknown", a group of anarchists facing conspiracy charges.[41] During the performance Socialist Workers Party supporters and other anti-fascists attacked British Movement neo-Nazis, triggering violence.[42] Crass afterwards argued that the leftists were largely to blame for the fighting, and organizations such as Rock Against Racism were causing audiences to become polarised into left- and right-wing factions.[43] Others (including the anarchist organisation Class War) were critical of Crass's position, stating that "like Kropotkin, their politics are up shit creek".[44] Many of the band's punk followers felt that they failed to understand the violence to which they were subjected from the right.[45]

"Rival Tribal Rebel Revel", a flexi disc single given away with the Toxic Grafity [sic] fanzine, was also a commentary about the events at Conway Hall attacking the mindless violence and tribalistic aspects of contemporary youth culture.[46] This was followed by the single, "Nagasaki Nightmare/Big A Little A". The strongly anti-nuclear lyrics of the first song were reinforced by the fold-out-sleeve artwork. It featured an article by Mike Holderness of Peace News magazine connecting the atomic power industry and the manufacture of nuclear weapons,[47] and a large poster-style map of nuclear installations in the UK. The other side of the record, "Big A Little A", was a statement of the band's anti-statist and individualist anarchist philosophy:

"Be exactly who you want to be, do what you want to do / I am he and she is she but you're the only you."[48]

1981: Penis Envy

Crass released their third album, Penis Envy, in 1981. This marked a departure from the hardcore-punk image The Feeding of the 5000 and Stations of the Crass had given the group. It featured more-complex musical arrangements and female vocals by Eve Libertine and Joy De Vivre (singer Steve Ignorant was credited as "not on this recording"). The album addressed feminist issues, attacking marriage and sexual repression.

The last track on Penis Envy, a parody of an MOR love song entitled "Our Wedding", was made available as a white flexi disc to readers of Loving, a teenage romance magazine. Crass tricked the magazine into offering the disc, posing as "Creative Recording And Sound Services". Loving accepted the offer, telling their readers that the free Crass flexi would make "your wedding day just that bit extra special".[49] A tabloid controversy resulted when the hoax was exposed, with the News of the World stating that the title of the flexi's originating album was "too obscene to print".[50] Despite Loving's annoyance, Crass had broken no laws.[51]

The album was banned by the retailer HMV,[52] and copies of the album were seized from the Eastern Bloc record shop by Greater Manchester Police under the direction of Chief Constable James Anderton.[53] The shop owners were charged with displaying "obscene articles for publication for gain".[54] The judge ruled against Crass in the ensuing court case, although the decision was overturned by the Court of Appeal (except the lyrics to one song, "Bata Motel", which were upheld as "sexually provocative and obscene").[55]

1982–1983: Christ – The Album and strategy change

The band's fourth LP, 1982's double set Christ - The Album, took almost a year to record, produce and mix (during which the Falklands War broke out and ended). This caused Crass to question their approach to making records. As a group whose primary purpose was political commentary, they felt overtaken and made redundant by world events:

The speed with which the Falklands War was played out and the devastation that Thatcher was creating both at home and abroad, forced us to respond far faster than we had ever needed to before. Christ – The Album had taken so long to produce that some of the songs in it, songs that warned of the imminence of riots and war, had become almost redundant. Toxteth, Bristol, Brixton and the Falklands were ablaze by the time that we released. We felt embarrassed by our slowness, humbled by our inadequacy.[52]

Subsequent releases (including the singles "How Does It Feel? (to Be the Mother of a Thousand Dead)" and "Sheep Farming in the Falklands" and the album Yes Sir, I Will) saw the band's sound go back to basics and were issued as "tactical responses" to political situations.[56] They anonymously produced 20,000 copies of a flexi-disc with a live recording of "Sheep Farming...", copies of which were randomly inserted into the sleeves of other records by sympathetic workers at the Rough Trade Records distribution warehouse to spread their views to those who might not otherwise hear them.[57]

Direct Action and internal debates

From their early days of spraying stencilled anti-war, anarchist, feminist and anti-consumerist graffiti messages in the London Underground and on billboards,[58] Crass was involved in politically motivated direct action and musical activities. On 18 December 1982, the band helped co-ordinate a 24-hour squat in the empty west London Zig Zag club to prove "that the underground punk scene could handle itself responsibly when it had to and that music really could be enjoyed free of the restraints imposed upon it by corporate industry".[59]

In 1983 and 1984, Crass were part of the Stop the City actions co-ordinated by London Greenpeace[60] which foreshadowed the anti-globalisation rallies of the early 21st century.[61] Support for these activities was provided in the lyrics and sleeve notes of the band's last single, "You're Already Dead", expressing doubts about their commitment to non-violence. It was also a reflection of disagreements within the group, as explained by Rimbaud: "Half the band supported the pacifist line and half supported direct and if necessary violent action. It was a confusing time for us, and I think a lot of our records show that, inadvertently".[62] This led to introspection within the band, with some members becoming embittered and losing sight of their essentially positive stance.[63] Reflecting this debate, the next release under the Crass name was Acts of Love: classical-music settings of 50 poems by Penny Rimbaud, described as "songs to my other self" and intended to celebrate "the profound sense of unity, peace and love that exists within that other self".[64]

Thatchergate

Another Crass hoax was known as the "Thatchergate tapes",[65] a recording of an apparently accidentally overheard telephone conversation (due to crossed lines). The tape was constructed by Crass from edited recordings of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. On the 'rather clumsily' forged tape, they appear to discuss the sinking of HMS Sheffield during the Falklands War and agree that Europe would be a target for nuclear weapons in a conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union.[65]

Copies were leaked to the press via a Dutch news agency during the 1983 general election campaign.[66] The U.S. State Department and British Government believed the tape to be propaganda produced by the KGB (as reported by the San Francisco Chronicle[67] and The Sunday Times).[65] Although the tape was produced anonymously, The Observer linked the tape with the band.[68] Previously classified government documents made public in January 2014 under the UK's 'Thirty Year Rule' reveal that the prime minister was personally aware of the tape and had discussed it with her cabinet.[69]

1984: Breakup

Questions about the band in Parliament and an attempted prosecution by Conservative Party MP Timothy Eggar under the UK's Obscene Publications Act for their single, "How Does It Feel...",[70] made them question their purpose:

We found ourselves in a strange and frightening arena. We had wanted to make our views public, had wanted to share them with like minded people, but now those views were being analysed by those dark shadows who inhabited the corridors of power (…) We had gained a form of political power, found a voice, were being treated with a slightly awed respect, but was that really what we wanted? Was that what we had set out to achieve all those years ago?[52]

The band had also incurred heavy legal expenses for the Penis Envy prosecution;[55] this, combined with exhaustion and the pressures of living and operating together, finally took its toll.[52] On 7 July 1984, the band played a benefit gig at Aberdare, Wales, for striking miners, and on the return trip guitarist N. A. Palmer announced that he intended to leave the group.[71] This confirmed Crass's previous intention to quit in 1984, and the band split up.[72]

The group's final release as Crass was the "Ten Notes on a Summer's Day" 12" single in 1986. Crass Records was closed down in 1992; its final release was Christ's Reality Asylum, a 90-minute cassette of Penny Rimbaud reading the essay he had written in early 1977 that gave him the impetus to form Crass.

On 11 July 2024, the full 7 July 1984 concert was released as a free download to celebrate its 40th anniversary, albeit as a poor and upscaled tape transfer.

Crass Collective, Crass Agenda and Last Amendment

In November 2002 several former members arranged Your Country Needs You, a concert of "voices in opposition to war", as the Crass Collective. At Queen Elizabeth Hall on London's South Bank, Your Country Needs You included Benjamin Britten's War Requiem and performances by Goldblade, Fun-Da-Mental, Ian MacKaye and Pete Wright's post-Crass project, Judas 2.[73] In October 2003 the Crass Collective changed their name to Crass Agenda,[74] with Rimbaud, Libertine and Vaucher working with Matt Black of Coldcut and jazz musicians such as Julian Siegel and Kate Shortt. In 2004 Crass Agenda spearheaded a campaign to save the Vortex Jazz Club in Stoke Newington, north London[75] (where they regularly played). In June 2005 Crass Agenda was declared to be "no more", changing its name to the "more pertinent" Last Amendment.[76] After a five-year hiatus, Last Amendment performed at the Vortex in June 2012.[77] Rimbaud has also performed and recorded with Japanther and the Charlatans. A "new" Crass track (a remix of 1982's "Major General Despair" with new lyrics), "The Unelected President", is available.[78]

2007: Ignorant's The Feeding of the 5000

On 24 and 25 November 2007, Steve Ignorant performed Crass' The Feeding of the 5000 album live at the Shepherd's Bush Empire with a band of "selected guests".[79][80] Other members of Crass were not involved in these concerts. Initially Rimbaud refused Ignorant permission to perform Crass songs he had written, but later changed his mind: "I acknowledge and respect Steve's right to do this, but I do regard it as a betrayal of the Crass ethos".[81] Ignorant had a different view: "I don't have to justify what I do...Plus, most of the lyrics are still relevant today. And remember that three-letter word, 'fun'?"[81]

2010: Crassical Collection reissues

In 2010 it was announced that Crass would release The Crassical Collection,[82] remastered reissues of their back catalogue. Three former members objected, threatening legal action.[83][84] Despite their concerns the project went ahead, and the remasters were eventually released. First in the series was The Feeding of the 5000, released in August 2010. Stations of the Crass followed in October, with new editions of Penis Envy, Christ – The Album, Yes Sir, I Will and Ten Notes on a Summer's Day released in 2011 and 2012.[85] Critics praised the improved sound quality and new packaging of the remastered albums.[86][87]

2011: The Last Supper

In 2011 Steve Ignorant embarked on an international tour, entitled "The Last Supper". He performed Crass material, culminating with a final performance at the Shepherd's Bush Empire on 19 November.[88] Ignorant said that this was the last time he would sing the songs of Crass,[89] with Rimbaud's support; the latter joined him onstage for a drum-and-vocal rendition of "Do They Owe Us A Living", bringing the band's career full circle after 34 years: "And then Penny came on...and we did it, 'Do They Owe Us A Living' as we'd first done it all those years ago. As it started, so it finished".[88] Ignorant's lineup for the tour were Gizz Butt, Carol Hodge, Pete Wilson and Spike T. Smith, and he was joined by Eve Libertine for a number of songs.[88] The set list included a cover of "West One (Shine on Me)" by The Ruts, when Ignorant was joined onstage by the Norfolk-based lifeboat crew with whom he volunteers.[88]

Artwork and exhibitions

In February 2011, artist Toby Mott exhibited a portion of his Crass ephemera collection at the Roth Gallery in New York.[90][91] The exhibit featured artwork, albums (including 12" LPs and EPs), 7" singles from Crass Records and a complete set of Crass' self-published zine, Inter-National Anthem.

Artwork by Gee Vaucher and Penny Rimbaud, including a recording of the original 'Thatchergate Tape', featured as part of the 'Peculiar People' show at the Focal Point Gallery in Southend on Sea during the spring of 2016, part of a series of events celebrating the history of 'Radical Essex'.[92] Vaucher's painting 'Oh America', featuring an image of the Statue of Liberty hiding her face with her hands, was used as the front page of the UK Daily Mirror newspaper to mark the election of Donald Trump as US President on 9 November 2016.[93] From November 2016 to February 2017 the Firstsite art gallery in Colchester, hosted a retrospective of Gee Vaucher's artwork.[94]

In June 2016, "The Art of Crass" was the subject of an exhibition at the LightBox Gallery in Leicester curated by artist and technologist Sean Clark.[95] The exhibition featured prints and original artworks by Gee Vaucher, Penny Rimbaud, Eve Libertine, and Dave King. During the exhibition, Penny Rimbaud, Eve Libertine, and Louise Elliot performed "The Cobblestones of Love", a lyrical reworking of the Crass album "Yes Sir, I Will".[96] On the final day of the exhibition there was a performance by Steve Ignorant's Slice of Life. The exhibition is documented on The Art of Crass website.[97]

Influences

For Rimbaud the initial inspiration for founding Crass was the death of his friend Phil 'Wally Hope' Russell, as detailed in his book The Last of the Hippies: An Hysterical Romance. Russell had been placed in a psychiatric hospital after helping to set up the first Stonehenge free festival in 1974, and died shortly afterwards. Rimbaud believed that Russell was murdered by the State for political reasons.[98] Co-founder Ignorant has cited The Clash[10] and David Bowie[14] as major personal influences. Band members have also cited influences ranging from existentialism and Zen to situationism,[99] the poetry of Baudelaire,[100] British working class 'kitchen sink' literature and films such as Kes[101] and the films of Anthony McCall[99] (McCall's Four Projected Movements was shown as part of an early Crass performance).[102]

Crass have said that their musical influences were seldom drawn from rock, but more from classical music (particularly Benjamin Britten, on whose work, Rimbaud states, some of Crass' riffs are based),[103] free jazz,[55] European atonality,[55] and avant-garde composers such as John Cage[27] and Karlheinz Stockhausen.[55]

Legacy

Crass influenced the anarchist movement in the UK, the US and beyond. The growth of anarcho-punk spurred interest in anarchist ideas.[104] The band have also claimed credit for revitalising the peace movement and the UK Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament during the late 1970s and early 1980s.[105] Others contend that they overestimated their influence, their radicalising effect on militants notwithstanding. Researcher Richard Cross stated:

In their own writing, Crass somewhat overstate the contribution that anarcho-punk made to resuscitating the moribund Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in the early 1980s. The initiation of a new arms race, confirmed by plans to deploy first-strike Cruise and Pershing nuclear missiles across Europe, revived anti-nuclear movements across the continent, and would have arisen with or without the intercession of anarcho-punk. What Crass and anarcho-punk can quite legitimately claim is to have convinced a substantial number of radical youth to commit their energies to the most militant anti-militarist wings of the disarmament movement, which laid siege to nuclear installations across the country and which saw no conflict between its pacifist precepts and its willingness to commit acts of 'criminal damage' on the military property of the nuclear state.[106]

Crass' philosophical and aesthetic influences on 1980s punk bands were far-reaching.[107] A notable example is Washington, D.C.'s Dischord Records co-founder Ian MacKaye, who followed some of Crass' anti-consumerist and DIY principles in his own label and projects, particularly with the post-hardcore band Fugazi.[108][109] However, few mimicked their later free-form style (heard on Yes Sir, I Will and their final recording, Ten Notes on a Summer's Day).[110] Their painted and collage black-and-white record sleeves (by Gee Vaucher) may have influenced later artists such as Banksy (with whom Vaucher collaborated)[111] and the subvertising movement. Anti-folk artist Jeffrey Lewis's 2007 album, 12 Crass Songs, features acoustic covers of Crass material.[7] Brett Anderson, in his early teens at the time, was a big fan of the band, would play their records at home[112] and much later cited them in a radio interview, when asked about what band or artist had first made him want to get up on stage as a singer: "Crass! Their energy on stage was incredible, I was very impressed".

In an interview with The Guardian in 2016, the band was citied along with a number of other British Anarcho-punk bands of the early '80s as being an influence to the American avant-garde metal group Neurosis.[113]

Members

- Steve Ignorant (vocals)

- Eve Libertine (vocals)

- Joy De Vivre (vocals)

- N. A. Palmer (guitar)

- Phil Free (guitar)

- Pete Wright (bass, vocals)

- Penny Rimbaud (drums, vocals)

- Gee Vaucher (artwork, piano, radio)

- Mick Duffield (films)

- John Loder, sound engineer and founder of Southern Studios, is sometimes considered the "ninth member" of Crass. (died 2005)[114]

- Steve Herman (guitar; left shortly after their first performance and died on 4 February 1989)

Discography

(All released on Crass Records unless otherwise stated.)

LPs

- The Feeding of the 5000 (LP, 1978, 45 rpm, Small Wonder Records – UK Indie – No. 1. Reissued in 1980 as LP 33 rpm as The Feeding of the 5000 – Second Sitting, UK Indie – No. 11)

- Stations of the Crass (521984, double LP, 1979) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- Penis Envy (321984/1, LP, 1981) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- Christ – The Album (BOLLOX 2U2, double LP, 1982) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- Yes Sir, I Will (121984/2, LP, 1983) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- Ten Notes on a Summer's Day (catalog No. 6, LP, 1986, Crass Records) (UK Indie – No. 6)

Compilations and remastered editions

- Best Before 1984 (1986 – CATNO5; compilation album of singles) (UK Indie – No. 7)

- The Feeding of the 5000 (The Crassical Collection) (2010 – CC01CD remastered edition)

- Stations of the Crass (The Crassical Collection) (2010 – CC02CD remastered edition)

- Penis Envy (The Crassical Collection) (2010 – CC03CD remastered edition)

- Christ – The Album (The Crassical Collection) (2011 – CC04CD remastered edition)

- Yes Sir, I Will (The Crassical Collection) (2011 – CC05CD remastered edition)

- Ten Notes on a Summer's Day (The Crassical Collection) (2012 – CC06CD remastered edition)

Singles

- "Reality Asylum" / "Shaved Women" (CRASS1, 7", 1979) (UK Indie – No. 9)

- "Bloody Revolutions" / "Persons Unknown" (421984/1, 7" single, joint released with the Poison Girls, 1980) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- "Rival Tribal Rebel Revel" (421984/6F, one-sided 7" flexi disc single given away with Toxic Grafity [sic] fanzine, 1980)

- "Nagasaki Nightmare" / "Big A Little A" (421984/5, 7" single, 1981) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- "Our Wedding" (321984/1F, one-sided 7" flexi-disc single by Creative Recording And Sound Services made available to readers of teenage magazine Loving)

- "Merry Crassmas" (CT1, 7" single, 1981, Crass' stab at the Christmas novelty market) (UK Indie – No. 2)

- "Sheep Farming in the Falklands" / "Gotcha" (121984/3, 7" single, 1982, originally released anonymously as a flexi-disc) (UK Indie – No. 1 , UK Singles Chart: No 106)

- "How Does It Feel To Be The Mother of 1000 Dead?" / "The Immortal Death" (221984/6, 7" single, 1983) (UK Indie – No. 1)

- "Whodunnit?" (121984/4, 7" single, 1983, pressed in "shit-coloured vinyl") (UK Indie – No. 2, UK Singles Chart – No.119)

- "You're Already Dead" / "Nagasaki is Yesterday's Dog-End" / "Don't Get Caught" (1984, 7" single. UK Singles Chart – No.166)

Other

- Penny Rimbaud Reads From 'Christ's Reality Asylum' (Cat No. 10C, C90 cassette, 1992)

- Acts of Love – Fifty Songs to my Other Self by Penny Rimbaud with Paul Ellis, Eve Libertine and Steve Ignorant (Cat No. 1984/4, LP and book, 1984. Reissued as CD and book as Exitstencilisms Cat No. EXT001 2012)

- EXIT The Mystic Trumpeter – Live at the Roundhouse 1972, The ICES Tapes (pre Crass material featuring Penny Rimbaud, Gee Vaucher, John Loder and others) (Exit Stencil Music Cat No. EXMO2, CD and book, 2013)

Live recordings

- Christ: The Bootleg (recorded live in Nottingham, 1984, released 1989 on Allied Records)

- You'll Ruin It For Everyone (recorded live in Perth, Scotland, 1981, released 1993 on Pomona Records)

Videos

- Crass

- Christ: The Movie (a series of short films by Mick Duffield that were shown at Crass performances, VHS, released 1990)

- Semi-Detached (video collages by Gee Vaucher, 1978–84, VHS, 2001)

- Crass: There Is No Authority But Yourself (documentary by Alexander Oey, 2006) documenting the history of Crass and Dial House.

- Crass Agenda

- In the Beginning Was the WORD – Live DVD recorded at the Progress Bar, Tufnell Park, London, 18 November 2004

See also

Suggested viewing

- The Art of Punk - Crass (The Museum of Contemporary Art) (2013) - Documentary featuring the art of Dan King and Gee Vaucher

References

- ^ "In August 1977 Dave King went (...) As Dave exits stage left, Steve Ignorant returns to Dial House and (...) Crass was born." Berger, George (2006). The Story of Crass. Omnibus Press. p. 76.

- ^ Rimbaud, Penny (2004). Love Songs. Pomona Publishing. p. xxiv. ISBN 1-904590-03-9.

We believed that you could no more be a socialist [band] and signed to CBS (The Clash) than you could be an anarchist and signed to EMI

- ^ Anarchist Punk genre at AllMusic

- ^ Graham, Josh (3 December 2010). "Crass, the Anarcho-Punk Fountainhead, Is Coming to S.F. in March -- Sort Of". Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Reading And Rioting: A Louder Than Words Walk Through". The Quietus. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Gonsales, Erica (25 May 2011). "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes: Anthony McCall's Enchanting Film Installations". Creators.vice.com. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b Lynskey, Dorian (28 September 2007). "Jeffrey Lewis, 12 Crass Songs". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Iain Aitch (5 January 2001). "Country house anarchy". The Guardian.

- ^ Sleeve note on Bullshit Detector Volume 1 (Crass Records, cat no.421984/4): "Sometime in 1977 Rimbaud and Ignorant started messing around with a song called 'owe us a living'. They ran through it a few times and decided to form a band consisting of themselves. They called themselves Crass"

- ^ a b "At the end of the Clash gig there was all these people shouting and saying 'your shit!' and Joe Strummer stood there and said 'if you think you can do any better go ahead and start your own band.' And I was like what a great idea!" "Steve Ignorant Interview". Punk77.co.uk.

- ^ Rimbaud, P; "...EXIT – 'The Mystic Trumpeter, Live at the Roundhouse 1972'" accompanying booklet, Exitstencil Recordings 2013

- ^ Rimbaud, P (2004). Love Songs. Pomona Publishing. p. xxi. ISBN 1-904590-03-9.

- ^ Glasper 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b Rimbaud 1999a, p. 99.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 86.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 93.

- ^ a b "Steve Ignorant interviewed". Punk77.co.uk. 2007.

- ^ a b Rimbaud, P; "...In Which Crass Voluntarily Blow Their Own", sleeve note essay included with Best Before 1984 album

- ^ ""Banned from the Roxy" from Feeding the 5000". Small Wonder Records. 1978.

- ^ Rimbaud, Penny (1977). ""Crass at the Roxy" from International Anthem 1". Archived from the original on 1 December 2005.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 103.

- ^ a b Glasper 2007, p. 23.

- ^ a b Berger 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Glasper 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Rimbaud 1999a, p. 90.

- ^ a b "Crass interview". New Crimes (3). Winter 1980.

- ^ "Crass interview". The Leveller (25). April 1979.

- ^ McKay 1996, p. 90.

- ^ McKay 1996, p. 89.

- ^ McKay 1996, p. 88.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 108: "They were very difficult to film, because with Super-8 you needed far more light than was available at a Crass gig – all you'd get was shadows and light – that would be about it. So it was a bit pointless filming the gigs. I did try asking for maybe 60 watt bulbs instead of 40 but there was no deal" – Mick Duffield

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 185.

- ^ George Berger (4 November 2009). The Story of Crass. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857120120.

- ^ Maria Raha (2004). Cinderella's Big Score: Women Of The Punk And Indie Underground. Basic Books. p. 96. ISBN 9781580051163.

- ^ Ignorant, Steve (2010). The Rest is Propaganda. Southern Records. p. 167.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 137.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Rimbaud, P; sleeve notes to 'The Crassical Collection; Stations of the Crass' Crass Records, 2010

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 169.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 145.

- ^ Lux, Martin (2006). Anti-Fascist. Phoenix Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-948984-35-8.

- ^ "Anarchy in UK: Crass interviewed: 1979". greengalloway. Blogspot. 23 October 2007.

But Crass blame this on Rock Against Racism which, they allege, has polarised youth. "If you're not in RAR then you're a Nazi. Now we're sandwiched between left-wing violence and right-wing violence" – Crass interviewed in "New Society", 1979

- ^ Home, Stewart (1988). The Assault on Culture – Utopian Currents From Lettrisme to Class War. Aporia Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-948518-88-1.

like Kropotkin, their politics are up shit creek

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 149.

- ^ Mike Diboll (1979). "Crass – Toxic Grafity Fanzine". Kill Your Pet Puppy.

- ^ Mike Holderness, sleeve notes of "Nagasaki Nightmare/Big A Little A" single, Crass Records, 1980

- ^ Rimbaud, P; "Big A Little A", Crass Records 1980. Quoted in Love Songs p.57, Pomona Publishing ISBN 1-904590-03-9

- ^ "Southern Studios archive". Archived from the original on 9 March 2005.

- ^ "News of the World". 7 June 1981. p. 13. Archived from the original on 20 March 2005.

- ^ Berger 2006.

- ^ a b c d Rimbaud, P; "...In Which Crass Voluntarily Blow Their Own", sleeve note essay included with Best Before 1984 album

- ^ Petley, Julian. "Smashed Hits: Overview" (PDF).

- ^ "Flux of Pink Indians – F.C.T.U.L.P. – Alternative Mixes – 1984". Kill Your Pet Puppy. 21 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Rimbaud, P; sleeve notes to 'The Crassical Collection; Ten Notes on a Summer's Day' Crass Records, 2012

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 220.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 215.

- ^ McKay 1996, p. 87.

- ^ Glasper 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 247.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 248.

- ^ McKay 1996, p. 99.

- ^ Rimbaud 1999a, p. 249.

- ^ Sleeve notes of Acts of Love, Crass Records, 1985.

- ^ a b c "Crass – Thatchergate Tape And News Broadcasts – January 1984". Killyourpetpuppy.co.uk. 2 November 2007.

- ^ "Penny Rimbaud On How Crass Nearly Started World War 3". Vice.com. 3 January 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "San Francisco Chronicle". 30 January 1983. p. 10. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 238.

- ^ "Thatchergate Tapes" (PDF). January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2014.

- ^ "Protest songs: Marching to the beat of dissent". The Independent. 5 April 2012.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 254.

- ^ Robb, John (8 July 2009). "Could Crass exist today? | Music blog". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Freedom 6322 Nov 16th 2002 – Crass fail to show the way". A-Infos.

- ^ "babellabel.co.uk". Babellabel.co.uk.

- ^ Mossman, David (31 May 2004). "'This is the spiritual home of jazz and we ain't leaving'". The Guardian.

Penny (he's a bloke) has started a petition to keep the Vortex in Stoke Newington, and puts up a notice in the club saying: "This Is the Spiritual Home of Jazz and We Ain't Leaving." The resulting petition ends up going to the council with 3,000 signatures on it

- ^ "Southern Studios website archive 'LAST AMENDMENT events'". Archived from the original on 10 June 2005.

- ^ "Last Amendment | Transmissions from Southern". Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Crass music". Peace-not-war.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007.

- ^ "Steve Ignorant Official Website: Feeding Of The 5000". Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Crass frontman plans "The Feeding of the 5000" live performance". Punknews.org. 26 April 2007.

- ^ a b Aitch, Iain (19 October 2007). "Why should we accept any less than a better way of doing things?". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "The Feeding of the Five Thousand on Crassical Collection". Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Interviews: The Story of the Crassical Collection". Punknews.org. March 2013.

- ^ Capper, Andy (1 August 2010). "Anarchy And Peace, Litigated". Vice.com.

- ^ "Crass To Reissue Back Catalog". Ultimate Guitar.

- ^ "Crass - The Crassical Collection". Punknews.org. 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Christ the Album [The Crassical Collection] - Crass | Release Info". AllMusic.

- ^ a b c d Steve Ignorant (25 November 2011). "Blog post – Shepherds Bush". Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Steve Ignorant (25 November 2011). "Blog post – The Absolute last Supper".

- ^ "Curated Mag". January 2011. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "CRASS: selections from The Mott Collection 18th February – 18th March 2011 |". Crassthesecondsitting.wordpress.com. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Sword, Harry (1 June 2016). "Essex Has a Much More Radical History Than You'd Think". Vice.com.

- ^ Allen, Gavin (10 November 2016). "The story behind the Daily Mirror's historic US election front page". Mirror.co.uk.

- ^ "Gee Vaucher: Introspective". Firstsite.uk. 14 November 2016.

- ^ "The Art of Crass exhibition – curator Sean Clark reflects". Thehippiesnowwearblack.org.uk. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Penny Rimbaud, Eve Libertine and Louise Elliot : Leicester : live review". Louderthanwar.com. 15 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "The Art of Crass". Theartofcrass.uk. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Rimbaud, Penny (1982). The Last of the Hippies – An Hysterical Romance. Crass.

The court passed a verdict of suicide with no reference at all to the appalling treatment that had been the direct cause of it. [...] Our inquiries convinced us that what had happened was not an accident. The state had intended to destroy Wally's spirit, if not his life, because he was a threat, a fearless threat who they hoped they could destroy without much risk of embarrassment.

- ^ a b Berger 2006, p. 33.

- ^ "The Quietus - Features - A Quietus Interview - Penny Rimbaud On Crass & The Poets Of Transcendentalism & Modernism". The Quietus.

- ^ "Steve Ignorant: Crass Warrior". Litopia.com.

- ^ Berger 2006, p. 146.

- ^ McKay 1996, p. 95.

- ^ Savage, Jon (1991). England's Dreaming: Sex Pistols and Punk Rock. Faber & Faber. p. 584. ISBN 978-0571227204.

- ^ Rimbaud 1999a, p. 109.

- ^ "Hippies Now Wear Black/ Rich Cross". Killyourpetpuppy.co.uk. 10 February 2008.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (3 March 2011). "21: 'How does it feel to be the mother of one thousand dead?'". 33 Revolutions Per Minute. Faber and Faber. pp. 1773 and 1780. ISBN 978-0571277209. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Greene, Lora (26 July 2012). "4: New Wave". Combat Rock: A History of Punk (from Its Origins to the Present). BookCaps Study Guides. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-1621073154. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Dale, Pete (15 April 2016). "Introduction". Anyone Can Do It: Empowerment, Tradition and the Punk Underground. Routledge. p. 15 and 17. ISBN 978-1317180258. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Glasper 2007, p. 17.

- ^ "Banksy Santas Ghetto 2004". Artofthestate.co.uk. 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Brett Anderson". 23 August 2020.

- ^ Deller, Alex (3 November 2016). "Neurosis: 'Crass were the mother of all bands'". The Guardian. Kings Place, London. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Rimbaud, Penny (19 August 2005). "John Loder obituary". The Guardian. London.

Bibliography

- Berger, George (2006). The Story of Crass. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-012-0.

- Bounds, Philip (2014). "Anarchy, for a While". Notes from the End of History. London: Merlin Press.

- Cogan, Brian (2007). ""Do They Owe Us a Living? Of Course They Do!" Crass, Throbbing Gristle, and Anarchy and Radicalism in Early English Punk Rock". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 1 (2): 77–90. doi:10.1353/jsr.2008.0004. ISSN 1930-1189. JSTOR 41887578. S2CID 143586670. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Cross, Richard (2004). "The Hippies Now Wear Black: Crass and the anarcho-punk movement, 1977–1984". Socialist History (26). Socialist History Society. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- Cross, Richard (2010). "'There Is No Authority But Yourself': The Individual and the Collective in British Anarcho-Punk" (PDF). Music and Politics. 4 (2). ISSN 1938-7687. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Glasper, Ian (2007). The Day the Country Died: A History of Anarcho Punk 1980 to 1984. Cherry Red Books. ISBN 978-1-901447-70-5.

- Ignorant, Steve; Pottinger, Steve (2010). The Rest is Propaganda. Southern Records. ISBN 978-0-9566746-0-9.

- McKay, George (1996). "Chapter three: 'CRASS 621984 ANOK4U2'". Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance since the Sixties. Verso Books. ISBN 1-85984-028-0.

- McKay, George (2 September 2019). ""They've Got a Bomb": Sounding Anti-nuclearism in the Anarcho-punk Movement in Britain, 1978–84". Rock Music Studies. 6 (3): 217–236. doi:10.1080/19401159.2019.1673076. S2CID 213764792.

- Mott, Toby (2011). Crass 1977 – 1984. PPP Editions.

- Rimbaud, Penny (1999a). Shibboleth: my revolting life. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-873176-40-5.

- Rimbaud, Penny (1999b). The Diamond Signature. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-873176-55-9.

- Rimbaud, Penny (2004). Love Songs. Pomona Books. ISBN 978-1-904590-03-3.

- Vaucher, Gee (1999). Crass Art and other Post Modern Monsters. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-873176-10-8.

- A Series of Shock Slogans and Mindless Token Tantrums. Exitstencil Press. 1982. (originally issued as a pamphlet with the LP Christ – The Album, much of the text is now published online at "Southern Records". Archived from the original on 4 April 2005.)

- International Anthem: A Nihilist Newspaper for the Living. Exitstencil Press. 1977–81. (see "Crass Discography". Southern Records. Archived from the original on 15 April 2003. Retrieved 6 April 2003.)

External links

- Crass

- Anarcho-punk groups

- Anti-consumerist groups

- English art rock groups

- British hardcore punk groups

- Political music groups

- DIY culture

- English anti-fascists

- British critics of Christianity

- British critics of religions

- English punk rock groups

- Musical groups established in 1977

- Musical groups disestablished in 1984

- Squatters' movements

- Underground punk scene in the United Kingdom

- 1977 establishments in England