Battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily-armored warship with a main battery consisting of the largest caliber of guns. It is larger, better-armed and better-armored than cruisers and destroyers.

Battleships have evolved a great deal over time, as designs continually adapt technological advances to maintain an edge. The word battleship was coined around 1794 and is a shortened form of line of battle ship, the dominant warship in the Age of Sail.[1] The term came into formal use in the late 1880s to describe a developed type of ironclad warship,[2] and by the 1890s design had become relatively standard on what is now known as the pre–Dreadnought battleship. In 1905 HMS Dreadnought heralded a revolution in battleship design, and for many years modern battleships were referred to as dreadnoughts.

More than a type of war vessel, battleships constituted a potent symbol of national might and naval domination.[3] For decades, the numbers and abilities of battleships were a major factor in diplomacy and military strategy. The global arms race in battleship construction in the early 1900s was a significant factor in the origins of the First World War, which saw a clash of huge battlefleets at the Battle of Jutland. The construction of battleships was limited by the Naval Treaties of the 1920s and 1930s, but battleships both old and new were deployed during World War II.

Despite this record, some historians and naval theorists question the value of the battleship. Aside from Jutland, there were few battleship clashes. And despite their great firepower and protection, battleships were vulnerable to much smaller, cheaper craft: initially the torpedo and mine, and later aircraft and the guided missile.[4] The growing range of engagement led to the battleship's replacement as the leading type of warship by the aircraft carrier during World War II, being retained into the Cold War only by the United States Navy for fire support purposes. These last battleships were removed from the U.S. Naval Vessel Register in March 2006.

The ship of the line

The ship of the line was a large, unarmored wooden sailing warship mounting a battery of up to 120 smoothbore and carronade guns. The ship of the line was a gradual evolution of a basic design dating as far back as the 1400s, but its basic design changed little between the adoption of line of battle tactics in the early 17th century and the end of the sailing battleship's heyday in the 1830s. From 1794, the alternative term 'line of battle ship' was contracted (informally at first) to 'battle ship' or 'battleship'.[1]

The sheer number of guns fired broadside meant that the sailing battleship could wreck any wooden vessel, smashing the hull and masts and killing the crew. However, the effective range of the guns was as little as a few hundred yards, and sail tactics were dependent on the wind.

The first major change to the ship of the line concept was the introduction of steam power as an auxiliary propulsion system. Steam power was gradually introduced to the navy in the first half of the 19th century. The French Navy brought the technology to maturity with the 90-gun Le Napoléon in 1850[5] — the first true steam battleship.[6] Napoleon was armed as a conventional ship-of-the-line, but her steam engines could give her a speed of 12 knots, regardless of the wind conditions: a potentially decisive advantage in a naval engagement. In the end, France and the United Kingdom were the only two countries to develop fleets of wooden steam screw battleships, although several other navies made some use of a mixture of screw battleships and paddle-steamer frigates. These included Russia, Turkey, Sweden, Naples, Prussia, Denmark and Austria.[3]

Ironclads

The adoption of steam power was only one of a number of technological advances which revolutionized warship design in the 19th century. The ship of the line was overtaken by the ironclad: powered by steam, protected by metal armor, and armed with guns firing high-explosive shells. The first Royal Navy ship to bear the formal designation 'battleship' was the ironclad HMS Warrior.[7]

Explosive shells

Wooden hull ships stood up comparatively well to solid shot, as e.g. shown in the 1866 battle of Lissa, where the old Austrian steam battleship Kaiser ranged across a confused battlefield, rammed an Italian ironclad and took a pounding of several 300 pound shells at point blank range. Despite losing her bowsprit and her foremast, and being set on fire, she was ready for action the very next day.[8] By contrast, guns which fired explosive shells were a major threat to wooden ships, and became more widespread following the invention of the Paixhans guns in 1841. In the Crimean War, the Russian Black Sea Fleet destroyed a flotilla of wooden Turkish ships at the Battle of Sinop in 1853. Later in the war French ironclad floating batteries used similar weapons against the defenses at Kinburn.[9]

Iron armor and construction

The development of high-explosive shells made the use of iron armor plate on warships necessary. By the end of the 1850s, the potential of iron as a construction material for large ships had been proven by the mammoth SS Great Eastern. In 1859 France launched La Gloire, the first ocean-going ironclad warship. She was developed as a ship of the line, but cut to one deck due to weight considerations. Although made of wood and reliant on sail for most of her journeys, La Gloire was fitted with a propeller, and her wooden hull was protected by a layer of thick iron armor.[10] Gloire prompted further innovation from the Royal Navy, anxious to prevent France from gaining a technological lead. The superior armored frigate Warrior followed La Gloire by only fourteen months, and both nations embarked on a programme of building new ironclads and converting existing screw ships of the line to armored frigate status.[11] Within two years, Italy, Austria, Spain and Russia had all ordered ironclad warships, and by the time of the famous clash of the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads at least eight navies possessed ironclad ships.[3]

Ironclad design saw wide experimentation. Different navies experimented with the positioning of guns, in turrets (like the USS Monitor), centre-batteries or barbettes, or with the ram as the principal weapon. As steam technology developed, masts were gradually removed from battleship designs. By the mid-1870s steel was used as a construction material alongside iron and wood. The French Navy's Redoutable, laid down in 1873 and launched in 1876, was a central battery and barbette warship which became the first battleship in the world to use steel as the principal building material.[13] Russia tried circular battleships, which turned out to be one of the most unusual, if not outright bad, battleship designs ever built: when the guns were fired the ship spun on its axis like a top.[4]

The pre-dreadnought

By the late 19th century, designs had gradually settled down what has become known as the pre-dreadnought battleship. These were heavily armored ships, mounting a mixed battery of guns in turrets, and without sails. The typical first-class battleship of the pre-dreadnought era displaced 15,000 to 17,000 tons, had a speed of 16 knots, and an armament of four 12-inch guns in two turrets fore and aft with a mixed-calibre secondary battery in turrets amidships around the superstructure.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). However, it was not until the 1880s that similar designs were widespread,[4] and the type was perfected in the 1890s with the adoption of steel construction and armor.

The 12-inch main guns were the principal weapons for battleship-to-battleship combat. They were very slow-firing. The intermediate and secondary batteries had two roles. Against major ships, it was thought a 'hail of fire' from quick-firing secondary weapons could distract enemy gun crews by inflicting damage to the superstructure, and they would be more effective against smaller ships such as cruisers. Smaller guns (12-pounders and smaller) were reserved for protecting the battleship against the threat of torpedo attack from destroyers and torpedo boats.[14]

The beginning of the pre-dreadnought era saw Britain's attempt to assert its naval might. For many years previously, Britain had taken naval supremacy for granted, and expensive naval projects were criticised by political leaders of all inclinations.[3] However, in 1888, a war scare with France and the build-up of the Russian navy gave added impetus to naval construction, and the British Naval Defence Act of 1889 laid down a new fleet including eight new battleships. The principle that Britain's navy should be more powerful than the two next most powerful fleets combined was also enshrined. This policy was designed to deter French and Russian battleship-building, but both nations nevertheless expanded their fleets with more and better pre-dreadnoughts in the 1890s.[3]

In the last years of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th, the battleship building race became defined by conflict between Britain and Germany. The German naval laws of 1898 and 1890 authorised a fleet of 38 battleships, a vital threat to the balance of naval power.[3] Britain answered with further shipbuilding, but by the end of the pre-dreadnought era, British supremacy at sea had markedly weakened. In 1883, the United Kingdom had 38 battleships, twice as many as France and almost as many as the rest of the world put together. By 1897, Britain's lead was far less due to competition from France, Germany, and Russia, as well as the development of pre-dreadnought fleets in Italy, the United States and Japan.[15] Turkey, Spain, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Chile and Brazil all had second-rate fleets led by armored cruisers, coast service battleships or monitors.[16]

Pre-dreadnoughts continued the technical innovation of the ironclad. Turrets, armor plate, and steam engines were all improved over the years, and torpedo tubes were introduced. A small number of designs, including the American Kearsarge and Virginia classes, experimented with all or part of the 8-inch intermediate battery superimposed over the 12-inch primary, an arrangement called 'superfiring'. Results were poor: recoil factors and blast effects resulted in the 8-inch battery being completely unusable, and the inability to separately train the primary and intermediate armament led to significant tactical limitation. Even though such innovative designs saved weight (a key reason for their inception), they proved too cumbersome in practice.[17]

The Dreadnought era

In 1906, the revolutionary HMS Dreadnought made existing battleships obsolete. Combining an 'all-big-gun' armament of ten 12-inch (305 millimetre) rifles with unprecedented speed and protection, Dreadnought prompted navies worldwide to re-evaulate their battleship building programmes. The product of British technical superiority and the willpower of Admiral Jackie Fisher, Dreadnought was no bolt from the blue. The concept of an all-big-gun ship had been in circulation for several years, and the Japanese had even laid down an all-big-gun battleship in 1904.[18] The arrival of the Dreadnoughts sparked an arms race, principally between Britain and Germany but reflected worldwide, as the new class of warships became a crucial symbol of national power.

Technical development continued rapidly through the Dreadnought era, with step changes in armament, armor and propulsion meaning that ten years after Dreadnought's commissioning much more powerful ships were being built. These more powerful vessels were known as super-Dreadnoughts.

The origin of the Dreadnought

The Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti first articulated the concept of an all-big-gun battleship in 1903, stressing a large armored warship with a single caliber of guns as its only armament. When the Italian Navy did not pursue his ideas, Cuniberti wrote an article in Jane's propagating his concept, proposing the "ideal" future British battleship of 17,000 tons, with a main battery of twelve 12-inch (305 mm) guns, 300 mm belt armor, and speed of 24 knots (44 km/h).[19]

The battleship Satsuma of the Imperial Japanese Navy became the first ship in the world to be designed (1904) and laid down (May 15th, 1905) as an all-big-gun battleship, although her armament would ultimately not be completed to specifications due to shortages of the British 12-inch Armstrong guns. Satsuma retained triple-expansion steam engines, though her sister ship Aki, completed in 1911, used turbines.

The Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) provided operational experience to validate the 'all-big-gun' concept. At the Battle of the Yellow Sea and the Battle of Tsushima, pre-Dreadnought fleets exchanged volleys of 12 in shells at ranges of 7 to 11 kilometres, beyond the range of the secondary batteries. It is often held that these engagements demonstrated the importance of the 12-inch gun over its smaller counterparts, though some historians take the view that the secondary batteries of the pre-Dreadnoughts were just as decisive as the larger weapons.[3] None of this was lost on the head of the British Admiralty, Jackie Fisher. As early as 1904, Fisher had been convinced by the need for fast, powerful ships with an all-big-gun armament. If Tsushima influenced his thinking, it was to persuade him of the need to standardise on 12-inch guns.[3] Fisher's concern was that submarines and destroyers would be equipped with torpedoes which had a longer effective range than battleship guns, making speed imperative for capital ships.[3] Fisher's preferred option for the Royal Navy was his brainchild, the battlecruiser: lightly armored but heavily armed with eight 12-inch guns and propelled to a remarkable speed of 25 knots by steam turbines.

It was to prove the revolutionary technology that the battleship HMS Dreadnought was laid down in 1905 and sped to completion by 1906. She carried ten 12-inch guns, had an 11 in armour belt, and was the first large ship powered by steam turbines. She mounted her guns in five turrets; three along the centreline (one forward and two aft) and two on the wings, giving her twice the broadside of anything else afloat. She retained a number of 12-pounder (3 inch or 76 mm) quick-firing cannon for use against destroyers and torpedo-boats. Her armor was strong enough that she could conceivably go head-to-head with any other ship afloat in a gun battle and win.[20] Dreadnought was to have been followed by three battlecruisers, their construction delayed to allow lessons from the Dreadnoughts construction to be used in their design. While Fisher may have intended Dreadnought to be the last Royal Navy battleship,[3] the design was so successful that he found little support for his plan to switch over to a battlecruiser navy. Although there were some problems with the ship (the design's wing turrets strained the hull when firing broadside, and the top of the thickest armor belt lay below the waterline when the ship was fully loaded), the Royal Navy promptly commissioned another six ships to a similar design in the Bellerophon and St Vincent classes.

The dreadnought arms race

In 1897, before the revolution in design brought about by Dreadnought, the Royal Navy had 62 battleships in commission or building: a lead of 26 over France and of 50 over Germany.[21] In 1906, the Royal Navy now had a lead of only one: the Dreadnought herself. The new class of ship prompted an arms race with major strategic consequences. Major naval powers raced to build their own dreadnoughts to catch up with the United Kingdom. Possession of modern battleships was not only vital to naval power, but as with nuclear weapons today, represented a nation's standing in the world.[3] Germany, France, Russia, Italy, Austria and the United States all began dreadnought programmes; and second-rank powers including Turkey, Argentina, Brazil and Chile commissioned dreadnoughts to be built in British and American yards.[22]

The Anglo-German arms race

See also: Causes of World War I

Britain and Germany had for some years been locked into a strategic struggle, as Germany asserted herself as a colonial as well as a European power. It was this threat which prompted the building of the Dreadnought and made a naval arms race between the two nations inevitable.

While Fisher's reorganisation of the Navy in 1904 and 1905 actually cut the Naval Estimates,[23] the pressing need for more and better ships to ensure naval superiority caused friction in the British government. The costs of maintaining the Royal Navy at a level capable of taking on the next two navies at the same time were immense.[24]

The first German response to Dreadnought came with the Nassau class, laid down in 1907, followed by the Helgoland class in 1909. Together with two battlecruisers — a type for which the Germans had less admiration than Fisher, but which could be built under authorisation for armored cruisers, rather than capital ships — these classes gave Germany a total of ten modern capital ships built or building in 1909. While the British ships were somewhat faster and more powerful than their German equivalents, a 12:10 ratio fell very short of the 2:1 ratio that the Royal Navy wanted to maintain.[3]

In 1909, the British Parliament authorised an additional four capital ships, holding out hope that Germany would be willing to negotiate a treaty about battleship numbers. If no such solution could be found, an additional four ships would be laid down in 1910. Even this compromise solution meant (when taken together with some social reforms) raising taxes enough to prompt a constitutional crisis in Britain in 1909-10.

In 1910, the British eight-ship construction plan went ahead, including four Orion-class super-dreadnoughts, and augmented by battlecruisers purchased by Australia and New Zealand. In the same period of time, Germany laid down only three ships, giving Britain a superiority of 22 ships to 13. The British resolve demonstrated by their construction programme led the Germans to seek a negotiated end to the arms race. While the Admiralty's new target of a 60% lead over Germany was near enough to Tirpitz's goal of cutting the British lead to 50%, talks foundered on the question on whether British Commonwealth battlecruisers should be included in the count, as well as non-naval matters like the German demands for recognition of her ownership of Alsace-Lorraine.[3]

The pace of the Dreadnought race stepped up in both nations' 1910 and 1911 budgets, with Germany laying down four capital ships each year and Britain five. The tensions came to a head following the German Naval Law of 1912. This proposed a fleet of 33 German battleships and battlecruisers, outnumbering the Royal Navy in home waters. To make matters worse, the Austro-Hungarian Fleet was building 4 dreadnoughts, while the Italians had four and were building two more. Against such threats, the Royal Navy could no longer guarantee vital British interests. Britain was faced with a choice of building more battleships, withdrawing from the Mediterranean, or seeking an alliance with France. Further naval construction was unacceptably expensive at a time when social welfare provision was making calls on the budget. Withdrawing from the Mediterranean would mean a huge loss of influence, weakening British diplomacy in the Mediterranean and shaking the stability of the British Empire. The only acceptable option, and the one taken by First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, was to overturn a hundred years of splendid isolation and seek an alliance with France.[25]

In spite of these important strategic consequences, the 1912 Naval Law had little bearing on the battleship force ratios. Britain responded by laying down ten new super-Dreadnoughts in her 1912 and 1913 budgets—ships of the Queen Elizabeth and Royal Sovereign classes which introduced a further step change in armament, speed and protection—while Germany laid down only five, focusing resources on the Army.[3]

U.S. Navy dreadnoughts

The American South Carolina class battleships were the first all-big-gun-ships to be completed by one of Britain's rivals. The planning for the type had begun before the Dreadnought was launched, perhaps aided by secret briefing by sympathetic Royal Navy officials.[3] Construction began in 1906, after the completion of the Dreadnought, and the type had no turbines. Smaller than Dreadnought at 16,000 tons standard displacement, they carried eight twelve-inch guns in four twin turrets arranged in superfiring pairs fore and aft along the centreline of the keel. This arrangement gave South Carolina and her sister Michigan a broadside equal to Dreadnought's without requiring the cumbersome wing turrets that were a feature of the first few British dreadnought classes. The superfiring arrangement had not been proven until after South Carolina went to sea, and it was initially feared that the weakness of the previous Virginia class ship's stacked turrets would repeat itself. Half of the first ten U.S. dreadnoughts used the older and less efficient reciprocating engines rather than steam turbines. While reciprocating engines made many U.S. battleships slower than their British counterparts, they had a much greater range, something of great importance in the Pacific.

Japan

With the defeat of the Russians, the Japanese navy became concerned about the potential for conflict with the USA. Japanese theorist Sato Tetsutaro developed the concept that Japan needed a fleet at a minimum 70% the size of that of the USA to compete. However, Japan's first priority was to refit the pre–Dreadnoughts it had captured from Russia, and to complete the two Satsuma class ships as pre–Dreadnoughts. It was not until 1909 that Japan laid down her first Dreadnoughts, Kawachi and Settsu, while they were not complete until 1912. Two super–Dreadnoughts of the Fuso class and four Kongo–class battlecruisers were also laid down in 1912 and 1913, increasingly built from Japanese rather than imported components. While Japan adopted an 'eight–eight' Navy target — eight battleships and eight battlecruisers — it took until 1921 to hit the target, by which time the Washington Naval Treaty had negated it.[3]

Dreadnoughts in other countries

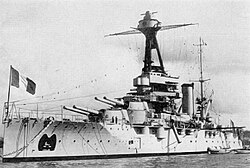

Compared to the other major naval powers France was slow to start building Dreadnoughts, instead finishing the planned Danton class of pre–Dreadnoughts, laying down five in 1907 and 1908. It was not until September 1910 that the first Dreadnoughts (of the Courbet class) were laid down, making France the eleventh nation to enter the Dreadnought race. The Courbets were followed by three super–Dreadnoughts of the Bretagne class; another five Normandie class ships were planned but cancelled on the outbreak of war. The Dreadnought arms race saw France drop from second to fifth in terms of naval power; however, the closer alliance with Britain made these reduced forces more than adequate for French needs.[3]

Even though Cuniberti had tried to promote the idea of an all-big-gun battleship in Italy well before the Dreadnought, it took until 1909 for Italy to lay down a Dreadnought of her own. The construction of Dante Alighieri was prompted by rumours of Austro-Hungarian Dreadnought building. A further five dreadnoughts of the Cavour class and Andrea Doria class followed as Italy sought to maintain its lead over Austria-Hungary. These ships remained the core of Italian naval strength until World War II. The subsequent Caracciolo-class were cancelled on the outbreak of WWI.

In January 1909, Austro-Hungarian admirals circulated a document calling for a fleet of four Dreadnoughts. However, a constitutional crisis in 1909–10 meant that no construction could be approved. In spite of this, two Dreadnoughts were laid down by shipyards on a speculative basis, and later approved along with an additional two. The resulting ships, all of the Tegetthoff class, were to be accompanied by a further four ships, but these were cancelled on the outbreak of World War I.

In June 1909, the Russian Empire laid down four dreadnoughts of the Gangut class for the Baltic Fleet and in 1911 three more Imperatritsa Mariya class dreadnoughts for the Black Sea.[26]

Spain commissioned three dreadnoughts of the España class, laying the first down in 1909. The Españas were the lightest Dreadnoughts ever built, and had the weakest armament (of only 8 305 mm guns). While built in Spain, the construction was reliant on British assistance.[27]

Brazil managed the remarkable achievement of being the third country with a Dreadnought under construction, laying down two in British shipyards in 1907. This sparked off a small-scale arms race in South America, as Argentina and then Chile commissioned Dreadnoughts. Argentina placed orders in American yards and Chile in Britain, meaning that both of Chile's two battleships were seized by the British on the outbreak of war. One of them was later returned to the Chilean government.

Turkey ordered two Dreadnoughts from British yards. Greece never ordered a Dreadnought, but in 1914 purchased two pre-Dreadnoughts from the United States Navy in 1914, renaming them Kilkis and Limnos in Royal Hellenic Navy service.

Many smaller navies ordered their ships from the British naval yards. At the near outbreak of WWI, the Royal Navy pressed ships under construction in British docks into their own service. This created some severe strains with the relations to the customers. The Ottoman Empire had two battleships near completion in Britain when the Royal Navy took over their ships. The Turks were outraged by the British move and the Germans saw an opening. Through skillful diplomacy and by handing over the battlecruiser Goeben and the cruiser Breslau the Germans maneuvered the Ottoman Empire into the Central Powers.[28]

The "super dreadnoughts"

Even after Dreadnought's commission, battleships continued to grow in size, guns, and technical proficiency as countries vied to have the best ships. By 1914 Dreadnought was outmoded.

The arrival of super–dreadnoughts is not as clearly identified with a single ship in the same way that the dreadnought era was initiated by HMS Dreadnought. However, it is commonly held to start with the British Orion class, and for the German navy with the König. What made them "super" was the unprecedented jump in displacement of 2,000–tons over the previous class, the introduction of the heavier 13.5 inch (343 mm) gun, and the distribution of all the main armament on the centreline of the keel. Thus, in the four years that separated the laying down of Dreadnought and Orion, displacement had increased by 25%, and weight of broadside had doubled. Some later super-Dreadnought designs, principally the Queen Elizabeth class, were described as fast battleships: battleships with battlecruiser speed.

The design weakness of super dreadnoughts, which distinguished them from post-World War I designs, was armor disposition. Their design placed emphasis on vertical protection which was needed in short range battles. These ships were capable of engaging the enemy at 20,000 metres, but were vulnerable to the angle of fire that came at such ranges. Post-war designs typically had 5 to 6 inches of deck armor to defend against this dangerous, plunging fire. The concept of zone of immunity became a major part of the thinking behind battleship design. Lack of underwater protection was also a weakness of these pre-World War I designs which were developed only as the threat of the torpedo became real. The United States Navy's "standard"-type battleships, beginning with the Nevada class, or "Battleship 1912", were designed with long-range engagements and plunging fire in mind; the first of these ships, USS Nevada, was laid down in 1912, five years before the Battle of Jutland taught the dangers of long-range fire to European navies. Important features of the standard battleships were "all or nothing" armor and "raft" construction, a philosophy under which only the parts of the ship worth armoring with the thickest armor that could be fitted to the ship were worth armoring at all, and that enough reserve buoyancy should be contained within the resulting armored "raft" to float the entire ship in the event that the unarmored bow and stern be thoroughly riddled and flooded.

World War I

War was almost an anticlimax for the great dreadnought fleets. There was no decisive clash of battlefleets to compare with the Battle of Trafalgar. The role of battleships was marginal to the great land struggle in France and Russia; and it was equally marginal to the First Battle of the Atlantic, the battle between German submarines and British merchant shipping.

By virtue of geography, the Royal Navy could keep the German German High Seas Fleet bottled up in the North Sea with relative ease. Both sides were aware that, because of the greater number of British dreadnoughts, a full fleet engagement would result in a British victory. The German strategy was therefore to try to provoke an engagement on favourable terms: either inducing a part of the Grand Fleet to enter battle alone, or to fight a pitched battle near the German coastline, where friendly fields, torpedo-boats and submarines could be used to even the odds.[29] The first two years of war saw conflict in the North Sea limited to skirmishes by battlecruisers at the Battle of Heligoland Bight and Battle of Dogger Bank and raids on the English coast. In the summer of 1916, a further attempt to draw British ships into battle on favourable terms resulted in a clash of the battlefleets in the Battle of Jutland: an indecisive engagement.[30]

In the other naval theatres there were no decisive pitched battles. In the Black Sea, Russian and Turkish battleships skirmished, but nothing more. In the Baltic, action was largely limited to convoy raiding and the laying of defensive minefields; the only significant clash of battleship squadrons was the Battle of Moon Sound at which one Russian dreadnought was lost. The Adriatic was in a sense the mirror of the North Sea: the Austro-Hungarian dreadnought fleet remained bottled up by British and French blockading fleets. And in the Mediterranean, the most important use of battleships was in support of the amphibious assault on Gallipoli.

The course of the war also illustrated the vulnerability of battleships to cheaper weapons. In September 1914, the U-boat threat to capital ships was demonstrated by successful attacks on British cruisers, including the sinking of three British armored cruisers by the German submarine U9 in less than an hour. Sea mines proved a threat the next month, when the recently commissioned British super-dreadnought Audacious struck a mine. By the end of October, British strategy and tactics in the North Sea had changed to reduce the risk of U-boat attack.[31] While Jutland was the only major clash of battleship fleets in history, the German plan for the battle relied on U-boat attacks on the British fleet; and the escape of the German fleet from the superior British firepower was effected by the German cruisers and destroyers closing on British battleships, causing them to turn away to avoid the threat of torpedo attack. Further near-misses from submarine attacks on battleships and casualties amongst cruisers led to growing paranoia in the Royal Navy about the vulnerability of battleships. By October 1916, the Royal Navy had essentially abandoned the North Sea, instructing the Grand Fleet not to go south of the Farne Islands unless adequately protected by destroyers. For the German part, the High Seas Fleet determined not to engage the British without the assistance of submarines; and since the submarines were more needed for commerce raiding, the fleet stayed in port for the remainder of the war.[32] Other theatres equally showed the role of small craft in damaging or destroying dreadnoughts. The two Austrian dreadnoughts lost in 1918 were the casualties of torpedo boats and of frogmen. The Allied capital ships lost in Gallipoli were sunk by mines and torpedo,[33] while a Turkish pre-dreadnought was caught in the Dardanelles by a British submarine.

The inter-war period

The inter-war period saw the battleship subjected to strict international limitations to prevent a costly arms-race breaking out.

For many years, German battleships simply ceased to exist. The Armistice with Germany required that most of the High Seas Fleet be disarmed and interned in a neutral port; largely because no neutral port could be found, the ships remained in British custody in Scapa Flow, Scotland. The Treaty of Versailles specified that the ships should be handed over to the British. However, instead most of these ships were scuttled by their German crews on 21 June 1919 just before the signature of the peace treaty. Versailles also limited the German Navy, preventing Germany from building or possessing any capital ships.[34]

While the victors were not limited by the Treaty of Versailles, many of the major naval powers were crippled from years of war. Faced with the prospect of a naval arms race against the USA, Britain was keen to conclude the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. This treaty limited the number and size of battleships that each major nation could possess, requiring Britain to accept parity with the USA and abandoning the British alliance with Japan.[35] The Washington treaty was followed by a series of other naval treaties, e.g. the First Geneva Naval Conference (1927), the First London Naval Treaty (1930), the Second Geneva Naval Conference (1932), and finally the Second London Naval Treaty (1936), which all meant limitations for major warships. These treaties would effectively end on 1 September 1939 with the beginning of World War II, but the ship classifications that had been agreed upon still apply.[36] The treaty limitations meant that fewer new battleships were launched from 1919–1939 than from 1905–1914. The treaties also inhibited development by putting maximum limits on the weights of ships. Designs like the projected British N3 battleship, the first American South Dakota class, and the Japanese Kii class — all of which continued the trend to larger ships with bigger guns and thicker armor — never got off the drawing board. Those designs which were commissioned during this period were referred to as treaty battleships.

Rise of the aircraft carrier

As early as 1914, the British Admiral Percy Scott prophesied that battleships would soon be made irrelevant by aeroplanes.[37] By the end of World War I, aeroplanes had successfully adopted the torpedo as a weapon.[38] A proposed attack on the German fleet at anchor in 1918 using the Sopwith Cuckoo carrier-borne torpedo-bomber was considered and rejected — but it was only so long before such a technique would be adopted.

In the 1920s, General Billy Mitchell of the United States Army Air Corps, believing that air forces had rendered navies around the world obsolete, presented his theory which claimed that aircraft could sink ships "under war conditions". This infuriated the U.S. Navy, but Mitchell was nevertheless allowed to conduct a series of bombing tests on battleships. In 1921, he successfully sank numerous ships, including the stationary German World War I battleship, the Ostfriesland and the American pre-dreadnought Alabama.

Although Mitchell had stressed "war-time conditions", the ships themselves were obsolete, had no damage control and were stationary defenseless targets. The sinking of Ostfriesland was accomplished only by violating agreed-upon rules that would have allowed Navy engineers to examine the effects of various munitions; Mitchell's airmen disregarded the rule and quickly sank the ship in a coordinated attack. This proved—at least to Mitchell—that surface fleets were obsolete. In 1922, he met the like-minded Italian air power theorist Giulio Douhet on a trip to Europe and soon after an excerpted translation of Douhet's The Command of the Air began to circulate in the Air Service.[39] While far from conclusive, Mitchell's test was significant in that it put proponents of the battleship against naval aviation on the back foot.[3]

Rearmament

Even when the threat of war became significant again in the late 1930s, battleship construction never regained the level of importance which it had held in the years before World War I. The "building holiday" imposed by the naval treaties meant that the building capacity of dockyards worldwide was relatively reduced, and the strategic picture had changed. The development of the strategic bomber meant that the navy was no longer the only method of projecting power overseas. And the development of the aircraft carrier meant that battleships had a rival for the resources available for capital ship construction.

In Germany, the ambitious Plan Z for naval rearmament was abandoned in favour of a strategy of submarine warfare supplemented by the use of Bismarck class battleships and battlecruisers as commerce raiders. In Britain, the most pressing need was for air defences and convoy escorts to safeguard the civilian population from bombing or starvation, and re-armament construction plans consisted of five ships of the King George V class. It was in the Mediterranean that navies remained most committed to battleship warfare. France intended to build six battleships of the Dunkerque and Richelieu classes, and the Italians two powerful Littorio-class ships. Neither navy built significant aircraft carriers. The USA preferred to spend limited funds on aircraft carriers until the South Dakota Class. Japan, also prioritising aircraft carriers, nevertheless began work on the two mammoth Yamato class battleships.[4]

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the Spanish navy consisted of two small dreadnought battleships, España and Jaime I. España, by then in reserve at the northwestern naval base of El Ferrol, fell into Nationalist hands in July 1936. The crew onboard Jaime I mutined and joined the Republican Navy. Thus each side would have one battleship; however, the Republican Navy generally lacked experienced officers. The Spanish battleships mainly restricted themselves to mutual blockades, convoy escort duties and shore bombardments—they rarely involved themselves in direct fighting against other surface units.[40] In April 1937, España ran onto a mine that had been laid by own forces and sank with little loss of life. In May 1937, Jaime I was damaged by Nationalist air attacks and a grounding incident. The ship was forced to go back to port to be repaired. There she was again hit by several aerial bombs. It was then decided to tow the battleship to a more secure port, but during the transport she suffered an internal explosion that caused 300 deaths and her total loss. Several Italian and German capital ships participated in the non-intervention blockade. On May 29, 1937, two Republican aircraft managed to bomb the German pocket battleship Deutschland outside Ibiza, causing severe damage and loss of life. Admiral Scheer retaliated two days later by bombarding the city of Almería causing much destruction, and the resulting Deutschland incident meant the end of German and Italian support for non-intervention.[41]

World War II

German battleships — obsolete pre-dreadnoughts — fired the first shots of World War II with the bombardment of the Polish garrison at Westerplatte;[42] and the final surrender of the Japanese Empire took place aboard a United States Navy battleship, the USS Missouri. Between the two events, it became clear that battleships were now essentially auxiliary and aircraft carriers the new principal ships of the fleet.

Battleships played a part in major engagements in Atlantic, Pacific and Mediterranean theatres; in the Atlantic, the Germans experimented with taking the battleship beyond conventional fleet action into an independent commerce raider. However, there were few battleship-on-battleship engagements. Battleships had little impact on the destroyer and submarine Battle of the Atlantic, and most of the decisive fleet clashes of the Pacific war were determined by aircraft carriers.

In the first year of the war, armored warships defied predictions that aircraft would dominate naval warfare. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau surprised and sank the aircraft carrier Glorious off western Norway in June 1940.[43] Although unescorted carriers still were considered vulnerable to attack by other ships, and therefore had to travel with escort, this engagement marked the last time a fleet carrier be sunk by surface gunnery. In the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, British battleships opened fire on the French battleships harboured in Algiers with their own heavy guns, and later pursued fleeing French ships with planes from aircraft carriers.

Taranto to Pearl Harbour

In late 1940 and 1941, a range of engagements across the globe saw battleships harassed by carrier aircraft.

The first example of the power of naval aviation was the British air attack on the Italian naval base at Taranto that took place on the night of 11 November–12 November 1940. The Royal Navy flew a small number of aircraft to attacking the Italian fleet at harbour. One Italian battleship was sunk and two damaged. Just as importantly the attack forced the Italian navy to change tactics and seek battle against the superior British navy, resulting in the defeat at the Battle of Cape Matapan.

The battleship war in the Atlantic was driven by the attempts of German capital ship commerce raiders—two battleships, the Bismarck and the Tirpitz, and two battlecruisers—to influence the Battle of the Atlantic by destroying Atlantic convoys supplying the United Kingdom. The superior numbers of British surface units devoted themselves to protecting the convoys, and seeking out and trying to destroy the German ships, assisted by both naval and land-based aircraft and by sabotage attacks. On 24 May 1941, during an attempt to break out into the North Atlantic, the battleship commerce raider Bismarck, was engaged by the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Hood. The Bismarck sank the Hood.[44] The Royal Navy hunted down Bismarck; an attack by Swordfish biplane torpedo-bombers from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal disabled her steering and allowed the British heavy units to catch up; Bismarck was sunk on May 27.[45]

On December 7, 1941 the Japanese launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Within a short time five of eight U.S. battleships were sunk or sinking, with the rest damaged. The Japanese had neutralized the U.S. battleship force in the Pacific region through an air attack, and thereby proven Mitchell's theory, showing the vulnerability of major warships lying at anchor, as at Taranto. The American aircraft carriers were however out to sea and evaded detection. They in turn would take up the fight, eventually turning the tide of the war in the Pacific. The sinking of the British battleship Prince of Wales and her escort, the battlecruiser HMS Repulse further demonstrated the vulnerability of a battleship to air attack, in this case while at sea without air cover. Both ships were on their way to assist in the defense of Singapore when they were caught by Japanese land-based bombers and fighters on December 10 1941. Prince of Wales has the distinction of being the first battleship sunk by aircraft while underway and able to defend herself.[46]

The Pacific battles

At many of the crucial battles of the Pacific, for instance Coral Sea and Midway, battleships were either absent or overshadowed as carriers launched wave after wave of planes into the attack at a range of hundreds of miles. Battleships in the Pacific ended up primarily performing shore bombardment and anti-aircraft defense for the carriers. Even the largest battleships ever constructed, Japan's Yamato class, which carried a main battery of nine 18-inch (457 millimetre) guns and were designed as a principal strategic weapon, were never given a chance to show their potential.[47]

In the Battle of Guadalcanal on November 15 1942, the United States battleships South Dakota and Washington fought and destroyed the Japanese battleship Kirishima.

The Battle off Samar, on 25 October 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf proved that battleships were still a lethal weapon. The American escort carriers of "Taffy 3" had a narrow escape from falling under the guns of the Japanese battleships Yamato, Kongō, Haruna and Nagato and their cruiser escort. American destroyers and aircraft attacked the battleships, enabling the American task force to disengage. Inexplicably, the Japanese fleet disengaged as well, despite being near to their intended target - the American amphibious landing forces at Leyte.

At Leyte Gulf, on 25 October 1944, six battleships, led by admiral Jesse Oldendorf of the U.S. 7th Fleet sank the Japanese admiral Shoji Nishimura's battleship Yamashiro and would have sunk Fusō if it had not already been broken in two by destroyer torpedoes moments earlier during the Battle of Surigao Strait. This engagement marked the last time in history when battleship faced battleship. It was also the day before this battle in a separate group further north that Musashi, sistership to Yamato, was sunk by aircraft attacks long before she could come within striking range of the American fleet.

Soviet and Finnish battles

During the Soviet-Finnish Winter War, the Soviet battleships Marat and Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya made several attempts to neutralize Finnish coastal batteries in order to implement a full naval blockade. The damage was however little on the Finnish side and the defenders bit back, claiming at least one hit on Marat.[48] During the German assault on the Soviet Union, the Soviet battleships would serve as convoy escorts during the evacuation of Tallinn, and as floating batteries during the siege of Leningrad.[49] The dense German and Finnish minefields and the submarine nets would effectively restrict Soviet traffic in the Gulf of Finland, forcing the larger vessels to remain at port.[50][51] The Marat would eventually be sunk at her moorings by the German Stuka pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel on 23 September 1941. The wreck continued in action as a floating battery for the remainder of the siege. Marat would later be refloated and both battleships served until the 1950s.[52]

Fire support

With the German capital-ship raiders sunk or forced to remain in port, shore bombardment became the focus of Allied battleships in the Atlantic. It was while covering the Allied invasion of Morocco that the Massachusetts fought Vichy French battleship Jean Bart on 27 October,1942. A concentration of six battleships occurred as part of Operation Neptune, in support of the D-Day landings in June 1944. D-Day also saw the humble sacrifice of two obsolete dreadnoughts, which were sunk as part of the breakwater around the Allied Mulberry harbours.

Response to the air threat

During the later stages of the war, the air defences of the Allied battleships had been significantly improved. The battleships were now literally covered with anti-aircraft guns, and with the arrival of the proximity fuse, radar, and carrier-based air cover, air attacks became much more risky. To counter these defenses, the Axis Powers implemented different methods. The Italians used with success their tested method of having frogmen delivering explosive charges to the ships, and managed to sink HMS Valiant and HMS Queen Elizabeth in the shallow waters of the harbor of Alexandria. Other more or less successful Italian methods included manned torpedoes and small motor assault boats, which were filled with explosives, aimed at the target, sped up to full speed, while the pilot catapulted himself out from the dashing craft.[53]

The Germans developed a series of stand-off weapons, e.g. the guided bomb Fritz X, which scored some early successes. On 9 September 1943, the Germans managed to sink the Italian battleship Roma and severely damage another battleship, the Italia, while they were underway to surrender. One week later, the Germans scored another hit with a Fritz X on the British battleship Warspite. The bomb penetrated six decks before exploding against the bottom of the ship, blowing a large hole in her. The ship took in a total of 5,000 tonnes of water, lost steam (and thus all power, both to the ship herself and to all her systems), and had to be taken in tow. She reached Malta but was out of action for the next 12 months.[54] The Japanese, on the other hand, tried to sink Allied ships through suicide air attacks - the so-called kamikaze. Although many U.S. battleships took hits by kamikaze, none were seriously damaged due to their thick armor. The kamikaze were much more successful against lesser-armored ships.[55]

The British further developed their ability to sink battleships in harbour with minisubs and very heavy bombs dropped by strategic bombers. The last active German battleship, Tirpitz, lurked until late into the war in Norwegian fjords protected by anti-submarine weapons and shore based anti-aircraft guns. She was severely damaged in September 1943 during Operation Source, a daring covert attack by British mini-subs, and ultimately sunk in harbour by RAF heavy bombers carrying massive tallboy bombs.[56][57]

As a result of the changing technology, plans for even larger battleships, the American Montana class, British Lion Class and Japanese "Super Yamato" class, were cancelled.[58] At the end of the war, almost all the world's battleships were decommissioned or scrapped. It is notable that most battleship losses occurred while in port. No battleship was lost to heavy bombers on the open seas, which was considered the most grave aerial peril to battleships prior to World War II, due to Billy Mitchell and the Ostfriesland experiment. The real aerial peril to battleships came from small, one to three-man dive bombers and torpedo bombers like the SBD Dauntless and TBF Avenger; in fact, it was the latter that sank the last battleship of the war, the Yamato, as she tried to make a run for Okinawa to prevent Allied landings there in May, 1945.

The Cold War

After World War II, several navies retained battleships, but it became clear that they were not worth the considerable cost. During the War it had become clear that battleship-on-battleship engagements like Leyte Gulf or the sinking of the Hood were the exception and not the rule, and that engagement ranges were becoming longer and longer, making heavy gun armament irrelevant. The armor of a battleship was equally irrelevant in the face of a nuclear attack, and nuclear missiles with a range of 100 kilometres or more could be mounted on the Soviet Kildin class destroyer and Whiskey class submarine by the end of the 1950s.

The remaining battleships met a variety of ends. USS Arkansas and Nagato were sunk during the testing of nuclear weapons in Operation Crossroads in 1946. Both battleships proved resistant to nuclear air burst but vulnerable to underwater nuclear explosions. The Italian Giulio Cesare was taken by the Soviets as reparations and renamed Novorossiysk; it was sunk by a German mine in the Black Sea on 29 October 1955. The two Doria class ships were scrapped in the late 1950s. The French Lorraine was scrapped in 1954, Richelieu in 1964 and Jean Bart in 1970. The United Kingdom's four surviving King George V class ships were scrapped in 1957, and Vanguard followed in 1960. All other surviving British battleships had been scrapped in the late 1940s. The Soviet Union's Petropavlovsk was scrapped in 1953, Sevastopol in 1957 and Gangut in 1959. Brazil's Minas Gerais was scrapped in 1954, and her sister ship São Paulo sank en route to the breakers during a storm in 1951. Argentina kept its two Rivadavia class ships until 1956. Chile kept Almirante Latorre (formerly HMS Canada) until 1959. The Turkish battlecruiser Yavuz (formerly the German Goeben, launched in 1911) was scrapped in 1976 after an offer to sell it back to Germany was refused. Sweden had several small coastal defense battleships, one of which, Gustav V, survived until 1970. The Russians also scrapped four large incomplete cruisers in the late 1950s, whilst plans to build new battleships were abandoned following the death of Stalin in 1953. There were also several old ships of the line still used as housing ships or storage depots. Of these, all but HMS Victory were sunk or scrapped by 1957.

The Iowa class battleships gained a new lease of life in the U.S. Navy as fire support ships. Shipborne artillery support is considered by the U.S. Marine Corps as more accurate, more effective and less expensive than aerial strikes. Radar and computer controlled gunfire could be aimed with pinpoint accuracy to target. The United States recommissioned all four Iowa class battleships for the Korean War and the New Jersey for the Vietnam War. These were primarily used for shore bombardment, New Jersey firing seven times more rounds against shore targets in Vietnam than she had in the Second World War.[59]

As part of Navy Secretary John F. Lehman's effort to build a 600-ship Navy in the 1980s, and in response to the commissioning of Kirov by the Soviet Union the United States recommissioned all four Iowa class battleships. On several occasions, battleships were support ships in carrier battle groups, or led their own battle groups in a battleship battle group. These were modernized to carry Tomahawk missiles, with New Jersey seeing action bombarding Lebanon, while Missouri and Wisconsin fired their 16 inch (406 mm) guns at land targets and launched missiles in the Gulf War of 1991. Wisconsin served as the TLAM strike commander for the Persian Gulf, directing the sequence of launches that marked the opening of Operation Desert Storm and firing a total of 24 TLAMs during the first two days of the campaign. This will most likely be the last combat action ever by a battleship.

All four Iowas were decommissioned in the early 1990s, making them the last battleships to see active service. USS Iowa and USS Wisconsin were, until fiscal year 2006, maintained in to a standard where they could be rapidly returned to service as fire support vessels, pending the development of a superior fire support vessel.[60] The U.S. Marine Corps believes that the current naval surface fire support gun and missile programs will not be able to provide adequate fire support for an amphibious assault or onshore operations.[61][62]

Today

With the decommissioning of the last Iowas, no battleships remain in service (including in reserve) with any navy worldwide. A number are preserved as museum ships, either afloat or in dry-dock. The USA has a large number of battleships on display. USS Massachusetts, North Carolina, Alabama, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Missouri,and Texas. Missouri, and New Jersey are now museums at Pearl Harbor and Camden, N.J. respectively. Wisconsin is a museum (at Norfolk, Va.), and was recently removed from the Naval Vessel Register. However, pending donation, the public can still only tour the deck, since the rest of the ship is closed off for dehumidification. The only other true battleship on display is the Japanese pre-Dreadnought Mikasa. A number of ironclads and ships-of-the-line are also preserved, including HMS Victory, Warrior, the Swedish Vasa, the Dutch Buffel and Schorpioen, and the Chilean Huáscar. The earliest ancestor of the battleship still on display is the sixteenth-century English war vessel Mary Rose.

Battleships in strategy and doctrine

Doctrine

Battleships were the embodiment of sea power. For Alfred Thayer Mahan and his followers, a strong navy was vital to the success of a nation, and control of the seas was vital for the projection of force on land and overseas. Mahan's theory dictated that the role of the battleship was to sweep the enemy from the seas.[63] The presence of battleships would make it impossible for the enemy to transport goods or armies, or to interfere with friendly trade and troop movements. While the work of escorting, blockading and raiding might be done by cruisers or smaller vessels, the presence of the battleship threatened any enemy cruisers which might seek an engagement with greatly superior force.

This school of thought was highly influential in naval and political circles throughout the age of the battleship,[64][3] and it called for a large fleet of the most powerful battleships possible. Mahan's work developed in the late 1880s and by the end of the 1890s it had a massive international impact.[3] The strength of Mahanian opinion was important in the development of the battleships arms races, and equally important in the agreement of the Powers to limit battleship numbers in the interwar era.

A related concept was that of a 'fleet in being': the idea that a fleet of battleships, simply by its presence, could tie down superior enemy resources and, even without a decisive battle, tip the balance of a conflict. This suggested that even for inferior naval powers a battleship fleet could have important strategic impact.[65]

Tactics

While the role of battleships in both World Wars reflected Mahanian doctrine, the details of battleship deployment were more complex. Unlike the ship-of-the-line, the battleships of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had significant vulnerability to torpedoes and mines, weapons which could be used by relatively small and inexpensive craft. The Jeune Ecole school of thought of the 1870s and 1880s recommended the placing of torpedo boats alongside battleships; the boats would hide behind the battleships until gun-smoke obscured visibility enough for them to dart out and fire their torpedoes.[3] While this concept was vitiated by the development of smokeless propellant, the threat from more capable torpedo craft remained. By the 1890s the Royal Navy had developed the first destroyers, small ships designed to intercept and drive off any attacking torpedo boats. During the First World War and subsequently, battleships were rarely deployed without a protective screen of destroyers.

Battleship doctrine emphasised the concentration of the battlefleet. In order for this concentrated force to be able to bring its power to bear on a reluctant opponent (or to avoid an encounter with a stronger enemy fleet), battlefleets needed some means of locating enemy ships beyond horizon range. This was provided by scouting forces; at various stages battlecruisers, cruisers, destroyers, airships, submarines and aircraft were all used. So for most of their history, battleships operated surrounded by squadrons of destroyers and cruisers. The North Sea campaign of the First World War illustrates how, despite this support, the threat of mine and torpedo attack seriously inhibited the operations of the Royal Navy Grand Fleet, the greatest battleship fleet of its time.

Strategic and diplomatic impact

The presence of battleships had a great psychological and diplomatic impact. Similar to possessing nuclear weapons today, the ownership of battleships made a country count for something.[3]

Even during the Cold War, the psychological impact of a battleship was significant. In 1946, USS Missouri was dispatched to deliver the remains of the ambassador from Turkey, and her presence in Turkish and Greek waters staved off a possible Soviet thrust into the Balkan region.[66] In September 1983, when Druze militia in Lebanon's Shouf Mountains fired upon U.S. Marine peacekeepers, the arrival of USS New Jersey stopped the firing. Gunfire from New Jersey later killed militia leaders.[67]

Value for money

Battleships were the largest and most complex, and hence the most expensive warships of their time; as a result, the value of investment in battleships has always been contested. As the French politician Etienne Lamy wrote in 1879, The construction of battleships is so costly, their effectiveness so uncertain and of such short duration, that the enterprise of creating an armored fleet seems to leave fruitless the perseverance of a people.[68] The Jeune Ecole school of thought of the 1870s and 1880s sought alternatives to the crippling expense and debatable utility of a conventional battlefleet, proposing what would nowadays be termed a sea denial strategy, based on fast, long-ranged cruisers for commerce raiding and torpedo boat flotillas to attack enemy ships attempting to blockade French ports. In many respects the ideas of the Jeune Ecole were ahead of their time; it was not until the twentieth century that efficient mines, torpedoes, subnmarines and aircraft were available allowing similar ideas to be implemented with much more potent effect.[69]

The determination of powers such as Imperial Germany to build battlefleets with which to confront much stronger rivals has been criticised by historians, who emphasise the futility of investment in a battlefleet which has no chance of matching its opponent in an actual battle.[3] According to this view, attempts by a weaker navy to compete head-to-head with a stronger one in battleship construction simply wasted resources which could have been better invested in attacking the enemy's points of weakness. In Germany's case, the British dependence on massive imports of food and raw materials proved to be a near-fatal weakness, once Germany had accepted the political risk of unrestricted submarine warfare against commercial shipping. Although the U-boat offensive in 1917-18 was ultimately defeated, it was successful in causing huge material loss and forcing the Allies to divert vast resources into Anti-submarine Warfare. This success, though not ultimately decisive, was nevertheless in sharp contrast to the inability of the German battlefleet to challenge the supremacy of Britain's far stronger fleet.

The problem for a maritime nation that does not maintain a balanced fleet, with at least some ability to contest a set-piece battle, is that it surrenders the use the sea for its own purposes, whether economic or military; and, in addition, lacks the ability to interdict enemy shipping movements which are protected by a sufficient escort. Such a strategy exposes the nation to blockade or even, in the worst case, invasion. In addition, while a navy optimised for sea denial operations may maximise its potential against a stronger opponent, it will be at a disadvantage against nations of similar strength of its own, but which have invested their resources in a more conventional fleet. For this reason, maritime nations which are unable to compete with the dominant naval power have usually sought to achieve an accommodation with that power, thereby allowing them to resource a balanced fleet with which to deal with their more direct rivals. Examples of this strategy are the French entente with Britain in the decade preceding the First World War; and the British withdrawal in 1921 from its alliance with Japan, in order to avoid a confrontation with the much more powerful USA.

Notes

- ^ a b "battleship" The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 4 Apr. 2000

- ^ Stoll, J. Steaming in the Dark?, Journal of Conflict Resolution Vol. 36 No. 2, Jun 1992

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Sondhaus, L. Naval Warfare 1815-1914, ISBN 0-415-21478-5

- ^ a b c d Lenton, H. T.: Krigsfartyg efter 1860

- ^ "Napoleon (90 guns), the first purpose-designed screw line of battleships", Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship (p39)

- ^ "Hastened to completion Le Napoleon was launched on 16 May 1850, to become the world's first true steam battleship", Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship (p39)

- ^ "The HMS Warrior Story". Permanent Joint Headquarters, Northwood. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Wilson, H. W.: Ironclads in Action - Vol 1, London, 1898, p. 240

- ^ Lambert, Andrew: Battleships in Transition, pp. 92-96

- ^ Gibbons, Tony: The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships, pp. 28-29

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 30-31

- ^ Gibbons, p. 93

- ^ Conway Marine, "Steam, Steel and Shellfire" (p. 96)

- ^ War at Sea in the Ironclad Age, Richard Hill, ISBN 0-304-35273-X

- ^ Kennedy, p. 209

- ^ Preston, Anthony: Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II

- ^ Preston, Anthony. (1972) Battleships of World War I, New York City: Galahad Books

- ^ Gibbons, p. 168

- ^ Cuniberti, Vittorio, "An Ideal Battleship for the British Fleet", All The World’s Fighting Ships, 1903, pp. 407-409.

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 170-171

- ^ The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Paul M. Kennedy, ISBN 0-333-35094-4, p. 209

- ^ The First World War, John Keegan, ISBN 0-7126-6645-1, p. 281

- ^ The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Paul M. Kennedy, ISBN 0-333-35094-4, p. 218

- ^ Greger, René: Schlachtschiffe der Welt, pp. 11, 15

- ^ The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Paul M. Kennedy, ISBN 0-333-35094-4, p. 224

- ^ Gibbons, p. 205

- ^ Gibbons, p. 195

- ^ Greger, René: Schlachtschiffe der Welt, p. 252

- ^ The First World War, John Keegan, ISBN 0-7126-6645-1, p. 289

- ^ Ireland, Bernard: Jane's War At Sea, pp. 88-95

- ^ Massie, Robert. Castles of Steel, London, 2005. pp127-145

- ^ The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Paul Kennedy, ISBN 0-333-35094-4, pp. 247-249

- ^ HMS Majestic and HMS Triumph were torpedoed by U.21; HMS Goliath was torpedoed by the Turkish torpedo boat Muavenet.

- ^ Ireland, Bernard: Jane's War At Sea, p. 118

- ^ Kennedy p 277

- ^ Ireland, Bernard: Jane's War At Sea, pp. 124-126, 139-142

- ^ Kennedy, op. cit., p. 199

- ^ From the Guinness Book of Air Facts and Feats (3rd edition, 1977): "The first air attack using a torpedo dropped by an aeroplane was carried out by Flight Commander Charles H. K. Edmonds, flying a Short 184 seaplane from HMS Ben-My-Chree on 12 August 1915, against a 5,000 ton (5,080 tonne) Turkish supply ship in the Sea of Marmara. Although the enemy ship was hit and sunk, the captain of a British submarine claimed to have fired a torpedo simultaneously and sunk the ship. It was further stated that the British submarine E14 had attacked and immobilised the ship four days earlier. However, on 17 August 1915, another Turkish ship was sunk by a torpedo of whose origin there can be no doubt. On this occasion Flight Commander C. H. Edmonds, flying a Short 184, torpedoed a Turkish steamer a few miles north of the Dardanelles. His formation colleague, Flight Lieutenant G. B. Dacre, was forced to land on the water owing to engine trouble but, seeing an enemy tug close by, taxied up to it and released his torpedo. The tug blew up and sank. Thereafter, Dacre was able to take off and return to the Ben-My-Chree

- ^ Ireland, Bernard: Jane's War At Sea, p. 126

- ^ Gibbons, p. 195

- ^ Greger, René: Schlachtschiffe der Welt, p. 251

- ^ Gibbons, p. 163

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 246-247

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 228-229

- ^ Zetterling, Niklas: Bismarck, pp. 248-260

- ^ Axell, Albert: Kamikaze, p. 14

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 262-263

- ^ Appel, Erik: Finland i krig 1939-1940, p. 182

- ^ Linder, Jan: Ofredens hav, pp. 50-51

- ^ Linder, Jan: Ofredens hav, pp. 50-51

- ^ Brunila, Kai: Finland i krig 1940-1944, pp. 100-108, 220-225

- ^ Greger, René: Schlachtschiffe der Welt, pp. 201

- ^ Taylor, A. J. P.: 1900-talet, p. 139

- ^ Ireland, Bernard: Jane's War At Sea, pp. 190-191

- ^ Axell, Albert: Kamikaze, pp. 205-213

- ^ Tamelander, Michael: Slagskeppet Tirpitz

- ^ Jacobsen, Alf R.: Dödligt angrepp

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 188-189

- ^ History of World Seapower, Bernard Brett, ISBN 0-603-03723-2, p. 236

- ^ "Iowa Class Battleship". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ The USMC has revised its Naval Surface Gunfire Support requirements, leaving some questions as to whether or not the Zumwalt class destroyer can meet the Marine qualifications

- ^ United States General Accounting Office. "Naval Surface Fires Support". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Massie, Robert K. Castles of Steel, London, 2005. ISBN 1-844-134113

- ^ Kennedy, op. cit., p2, p200, p206 et al.

- ^ "Fleet In Being", Globalsecurity.org, retrieved 18 March 2007

- ^ "USS Missouri". Directory of American Fighting Ships. Naval Historical Centre. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ "USS New Jersey". Directory of American Fighting Ships. Retrieved 2007-03-18.}}

- ^ Quoted inNet-Centric before its time: The Jeune École and Its Lessons for Today Erik J. Dahl US Naval War College Review, Autumn 2005, Vol. 58, No. 4

- ^ Dahl, op cit.

References

- Appel, Erik; et al. (2001). Finland i krig 1939-1940 - första delen (in Swedish). Espoo, Finland: Schildts förlag Ab. p. 261. ISBN 951-50-1182-5.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Archibald, E. H. H. (1984). The Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy 1897-1984. Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-1348-8.

- Axell, Albert; et al. (2004). Kamikaze - Japans självmordspiloter (in Swedish). Lund, Sweden: Historiska media. p. 316. ISBN 91-85057-09-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Brown, D. K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860-1905. Book Sales. ISBN 978-1-84067-529-2.

- Brown, D. K. (2003). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906-1922. Caxton Editions. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-84067-531-3.

- Brunila, Kai; et al. (2000). Finland i krig 1940-1944 - andra delen (in Swedish). Espoo, Finland: Schildts förlag Ab. p. 285. ISBN 951-50-1140-X.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) and Gray, Randal (Author) (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906-1921. Naval Institute Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) (1980). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1922-1946. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) and Lambert, Andrew (Ed.). Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The steam warship 1815-1905 - Conway's History of the Ship. Book Sales. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-78581-413-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers - A Technical Directory of all the World's Capital Ships from 1860 to the Present Day. London, UK: Salamander Books Ltd. p. 272. ISBN 0-51737-810-8.

- Greger, René (1993). Schlachtschiffe der Welt (in German). Stuttgart, Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. p. 260. ISBN 3-613-01459-9.

- Ireland, Bernard and Grove, Eric (1997). Jane's War At Sea 1897-1997. London: Harper Collins Publishers. p. 256. ISBN 0-00-472065-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jacobsen, Alf R. (2005). Dödligt angrepp - miniubåtsräden mot slagskeppet Tirpitz (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Natur & Kultur. p. 282. ISBN 91-27-09897-4.

- Kennedy, Paul M. (1983). The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery. London. ISBN 0-333-35094-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lambert, Andrew (1984). Battleships in Transition - The Creation of the Steam Battlefleet 1815-1860. London: Conway Maritime Press. p. 161. ISBN 0-85177-315-X.

- Lenton, H. T. (1971). Krigsfartyg efter 1860 (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Forum AB. p. 160.

- Linder, Jan; et al. (2002). Ofredens hav - Östersjön 1939-1992 (in Swedish). Avesta, Sweden: Svenska Tryckericentralen AB. p. 224. ISBN 91-631-2035-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Massie, Robert (2005). Castles of Steel - Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-844-134113.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships. first published Seeley Service & Co, 1957, published United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Anthony (Foreword) (1989). Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. London, UK: Random House Ltd. p. 320. ISBN 1-851-70494-9.

- Russel, Scott J. (1861). The Fleet of the Future. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare 1815-1914. London. ISBN 0-415-21478-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stilwell, Paul (2001). Battleships. New Your, USA: MetroBooks. p. 160. ISBN 1-58663-044-X.

- Tamelander, Michael; et al. (2006). Slagskeppet Tirpitz - kampen om Norra Ishavet (in Swedish). Norstedts Förlag. p. 363. ISBN 91-1-301554-0.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Taylor, A. J. P. (Red.); et al. (1975). 1900-talet: Vår tids historia i ord och bild; Part 12 (in Swedish). Helsingborg: Bokfrämjandet. p. 159.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Wetterholm, Claes-Göran (2002). Dödens hav - Östersjön 1945 (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Bokförlaget Prisma. p. 279. ISBN 91-518-3968-7.

- Wilson, H. W. (1898). Ironclads in Action - Vol 1. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zetterling, Niklas; et al. (2004). Bismarck - Kampen om Atlanten (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Nordstedts förlag. p. 312. ISBN 91-1-301288-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)

See also

- List of battleships

- List of battleship classes

- Fast battleship

- Naval ship

- Books by Robert K. Massie, including Dreadought and Castles of Steel

External links

- World Battleship Lists at hazegray.org

- List of early armored ships

- Maritimequest Battleships and Battlecruisers of the 20th century

- GlobalSecurity.org

- Video: Inside one of Missouri’s 16" gun room, about 1955. (Windows Media File)

- Comparison of project post-World War II battleship designs

- Comparison of the capabilities of seven WWII battleships

- An overview of the United States Navy Naval Surface Fire Support

- Development of US battleships, with timeline graph