Typeface

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. |

In typography, a typeface is a coordinated set of glyphs designed with stylistic unity. A typeface usually comprises an alphabet of letters, numerals, and punctuation marks; it may also include ideograms and symbols, or consist entirely of them, for example, mathematical or map-making symbols. The term typeface is often conflated with font, a term which, historically, had a number of distinct meanings before the advent of desktop publishing; these terms are now effectively synonymous when discussing digital typography. One notable and still-valid distinction between font and typeface is a font's status as a discrete commodity, while typeface designates a visual appearance or style.

The art and craft of designing typefaces is called type design. Designers of typefaces are called type designers, and often typographers. In digital typography, type designers are also known as font developers or font designers.

The size of typefaces and fonts is traditionally measured in points; point has been defined differently at different times, but now the most popular is the Desktop Publishing Point. Font size is also commonly measured in millimeters (mm) and qs (a quarter of a millimeter, kyu in romanized Japanese) and inches.

Etymology

The term font, a cognate of the word fondue, derives from Middle French fonte, meaning "(something that has been) melt(ed)", referring to type produced by casting molten metal at a type foundry. English-speaking printers have used the term fount for centuries to refer to the multi-part metal type used to assemble and print in a particular size and typeface.

Font, typeface and type family

A font is a set of glyphs (images) representing the characters from a particular character set in a particular typeface. In professional typography the term typeface is not interchangeable with the word font, which is defined as a given alphabet and its associated characters in a single size. For example, 8-point Caslon is one font, and 10-point Caslon is another. Historically, fonts came in specific sizes determining the size of characters, and in quantities of sorts or number of each letter provided. The design of characters in a font took into account all these factors.

As the range of typeface designs increased and requirements of publishers broadened over the centuries, fonts of specific weight (blackness or lightness) and stylistic variants—most commonly regular or roman as distinct to italic, as well as condensed — have led to font families, collections of closely-related typeface designs that can include hundreds of styles. A font family is typically a group of related fonts which vary only in weight, orientation, width, etc, but not design. For example, Times is a font family, whereas Times Roman, Times Italic and Times Bold are individual fonts making up the Times family. Font families typically include several fonts, though some, such as Helvetica, may consist of dozens of fonts. Helvetica, Century Schoolbook, and Courier are examples of three widely distributed typefaces.

History

For the origin and evolution of fonts, see History of western typography.

Type foundries have cast fonts in lead alloys from the 1450s until the present, although wood served as the material for some large fonts called wood type during the 19th century, particularly in the United States of America. In the 1890s the mechanization of typesetting allowed automated casting of fonts on the fly as lines of type in the size and length needed. This was known as continuous casting, and remained profitable and widespread until its demise in the 1970s. The first machine of this type was the Linotype, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler.

During a brief transitional period (circa 1950s – 1990s), photographic technology, known as phototypesetting, utilized tiny high-resolution images of individual glyphs on a film strip (in the form of a film negative, with the letters as clear areas on an opaque black background). A high-intensity light source behind the film strip projected the image of each glyph through an optical system, which focused the desired letter onto the light-sensitive phototypesetting paper at a specific size and position. This photographic typesetting process permitted optical scaling, allowing designers to produce multiple sizes from a single font, although physical constraints on the reproduction system used still required design changes at different sizes—for example, ink traps and spikes to allow for spread of ink encountered in the printing stage. Manually-operated photocomposition systems using fonts on filmstrips allowed fine kerning between letters without the physical effort of manual typesetting, and spawned an enlarged type-design industry in the 1960s and 1970s.

The mid-1970s saw all of the major typeface technologies and all their fonts in use: letterpress, continuous casting machines, phototypositors, computer-controlled phototypesetters, and the earliest digital typesetters—hulking machines with tiny processors and CRT outputs. From the mid-1980s, as digital typography has grown, users have almost universally adopted the American spelling font, which nowadays nearly always means a computer file containing scalable outline letterforms ("digital font"), in one of several common formats. Some fonts, such as Verdana, are designed primarily for use on computer screens.

Digital type

Digital fonts store the image of each character either as a bitmap in a bitmap font, or by mathematical description of lines and curves in an outline font, also called a vector font. When an outline font is used a rasterizing routine (in the application software, operating system or printer) renders the character outlines, interpreting the vector instructions to decide which pixels should be black and which ones white. Rasterization is straightforward at high resolutions such as those used by laser printers and in high-end publishing systems. For computer screens, where each individual pixel can mean the difference between legible and illegible characters, some digital fonts use hinting algorithms to make readable bitmaps at small sizes.

Digital fonts may also contain data representing the metrics used for composition, including kerning pairs, component-creation data for accented characters, glyph-substitution rules for Arabic typography and for connecting script faces, and for simple everyday ligatures like fl. Common font formats include METAFONT, PostScript Type 1, TrueType and OpenType. Applications using these font formats, including the rasterizers, appear in Microsoft and Apple Computer operating systems, Adobe Systems products and those of several other companies. Digital fonts are created with font editors such as Fontlab's TypeTool, FontLab Studio, Fontographer, or AsiaFont Studio.

Typeface anatomy

Typographers have developed a comprehensive vocabulary for describing the many aspects of typefaces and typography. Some vocabulary applies only to a subset of all scripts. Serifs, for example, are a purely decorative characteristic of typefaces used for European scripts, whereas the glyphs used in Arabic or East Asian scripts have characteristics (such as stroke width) that may be similar in some respects but cannot reasonably be called serifs and may not be purely decorative.

Serifs

| Sans Serif font | |

|

Serif font |

|

Serif font (serifs highlighted in red) |

Typefaces can be divided into two main categories: serif and sans serif. Serifs comprise the small features at the end of strokes within letters. The printing industry refers to typeface without serifs as sans serif (from French sans: "without"), or as grotesque (or, in German, grotesk).

Great variety exists among both serif and sans serif typefaces. Both groups contain faces designed for setting large amounts of body text, and others intended primarily as decorative. The presence or absence of serifs forms only one of many factors to consider when choosing a typeface.

Typefaces with serifs are often considered easier to read in long passages than those without. Studies on the matter are ambiguous, suggesting that most of this effect is due to the greater familiarity of serif typefaces. As a general rule, printed works such as newspapers and books almost always use serif typefaces, at least for the text body. Web sites do not have to specify a font and can simply respect the browser settings of the user. But of those web sites that do specify a font, most use modern sans serif fonts, because it is commonly believed that, in contrast to the case for printed material, sans serif fonts are easier than serif fonts to read on the low-resolution computer screen.

Proportion

A proportional typeface displays glyphs using varying widths, while a non-proportional or fixed-width or monospaced typeface uses fixed glyph widths.

Most people generally find proportional typefaces nicer-looking and easier to read, and thus they appear more commonly in professionally published printed material. For the same reason, GUI computer applications (such as word processors and web browsers) typically use proportional fonts. However, many proportional fonts contain fixed-width figures so that columns of numbers stay aligned.

Monospaced typefaces function better for some purposes because their glyphs line up in neat, regular columns. Most manually-operated typewriters and text-only computer displays use monospaced fonts. Most computer programs which have a text-based interface (terminal emulators, for example) use only monospace fonts in their configuration. Most computer programmers prefer to use monospace fonts while editing source code.

ASCII art usually requires a monospace font for proper viewing. In a web page, the <tt> </tt> or <pre> </pre> HTML tag most commonly specifies non-proportional fonts. In LaTeX, the verbatim environment uses non-proportional fonts.

Any two lines of text with the same number of characters in each line in a monospace typeface should display as equal in width, while the same two lines in a proportional typeface may have radically different widths. This occurs because wide glyphs (like those for the letters W, Q, Z, M, D, O, H, and U) use more space, and narrow glyphs (like those for the letters i, t, l, and 1) use less space than the average-width glyph when using a proportional font.

In the publishing industry, editors read manuscripts in fixed-width fonts for ease of editing. The publishing industry considers it discourteous to submit a manuscript in a proportional font.

Font metrics

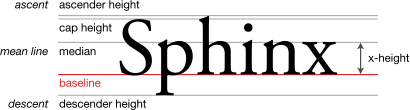

Most scripts share the notion of a baseline: an imaginary horizontal line on which characters rest. In some scripts, parts of glyphs lie below the baseline. The descent spans the distance between the baseline and the lowest descending glyph in a typeface, and the part of a glyph that descends below the baseline has the name "descender". Conversely, the ascent spans the distance between the baseline and the top of the glyph that reaches farthest from the baseline. The ascent and descent may or may not include distance added by accents or diacritical marks.

In the Latin, Greek and Cyrillic (sometimes collectively referred to as LGC) scripts, one can refer to the distance from the baseline to the top of regular lowercase glyphs (mean line) as the x-height, and the part of a glyph rising above the x-height as the "ascender". The distance from the baseline to the top of the ascent or a regular uppercase glyphs (cap line) is also known as the cap height.[1] The height of the ascender can have a dramatic effect on the readability and appearance of a font. The ratio between the x-height and the ascent or cap height often serves to characterise typefaces.

Types of typefaces

Because a plethora of typefaces have been created over the centuries, they are commonly categorized according to their appearance. At the highest level, one can differentiate between serif, sans-serif, script, blackletter, ornamental, monospace, and symbol typefaces. Historically, the first European fonts were blackletter, followed by serif, then sans-serif and then the other types.

Serif typefaces

Serif, or "roman", typefaces are named for the features at the ends of their strokes. Times Roman and Garamond are common examples of serif typefaces. Serif fonts are probably the most used class in printed materials, including most books, newspapers and magazines.

"Roman" and "oblique" are also terms used to differentiate between upright and italic variations of a typeface.

Sans serif typefaces

Sans serif designs appeared relatively recently in the history of type design. The two-line English so-called "Egyptian" font, released in 1816 by the William Caslon foundry in England apparently produced the first specimen. Sans serif fonts are commonly but not exclusively used for display typography such as signage, headings, and other situations demanding visual clarity rather than high readability. The text on web pages offers an exception: it appears mostly in sans serif font because serifs often detract from readability at the low resolution of displays.

The best-known sans serif font is Max Miedinger's Helvetica[citation needed], with others such as Futura, Gill Sans, Univers and Frutiger remaining popular over many decades. Arial is a widely-used sans serif font based on Helvetica, with minor simplifications in the glyphs for improved rendering on computer displays.

Script typefaces

Script typefaces simulate handwriting or calligraphy. They do not lend themselves to quantities of body text, as people find them harder to read than many serif and sans-serif typefaces; they are typically used for logos or invitations. Examples include Coronet and Zapfino.

Blackletter typefaces

Blackletter fonts, the earliest typefaces used with the invention of the printing press, resemble the blackletter calligraphy of that time. Many people refer to them as gothic script. Various forms exist including textualis, rotunda, schwabacher, and fraktur.

Ornamental typefaces

Ornamental (also known as "novelty" or sometimes "display") typefaces are used exclusively for decorative purposes, and are not suitable for body text. They have the most distinctive designs of all fonts, and may even incorporate pictures of objects, animals, etc. into the character designs. They usually have very specific characteristics (e.g. evoking the Wild West, Christmas, horror films, etc.) and hence very limited uses.

Monospaced typefaces

Monospaced fonts are typefaces in which every glyph is the same width (as opposed to variable-width fonts, where the "w" and "m" are wider than most letters, and the "i" is narrower). The first monospaced typefaces were designed for typewriters, which could only move the same distance forward with each letter typed. Their use continued with early computers, which could only display a single font. Although modern computers can display any desired typeface, monospaced fonts are still important for computer programming, terminal emulation, and for laying out tabulated data in plain text documents. Examples of monospaced typefaces are Courier, Prestige Elite, and Monaco.

Symbol typefaces

Symbol, or Dingbat, typefaces consist of symbols (such as decorative bullets, clock faces, railroad timetable symbols, CD-index, or TV-channel enclosed numbers) rather than normal text characters. Examples include Zapf Dingbats, Sonata, and Wingdings.

Typefaces based upon non-Roman alphabet writing systems

A group of decorative typefaces have been designed that take the form of the Roman alphabet but evoke another writing system. This group includes typefaces designed to appear as Arabic, Chinese, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Inuit. Application of these humorous, stereotypical types, can be seen in the use of a Chinese inspired face "Rickshaw" in a Chinese restaurant menu, the typeface "Faux Hebrew" used on the side of trucks for the New York City mover Nice Jewish Boy with Warehouse, or "Faux Arabic" used for Sami's Falafel Truck in Boston, Massachusetts.

Display faces

In the days of letterpress and phototypesetting, many of the most-commonly used typefaces were available in a "display face" variation. Display faces were created for best appearance at large "display" sizes (typically 36 points or larger) as might be used for a major headline in a newspaper or on the cover of a book. The main distinction of a display face was the lack of "ink traps," small indentations at the junctions of letter strokes. In smaller point sizes, these ink traps were intended to plug up when the letterpress was over-inked, providing some latitude in press operation while maintaining the intended appearance of the type design. At larger sizes these ink traps are not necessary, so display faces do not have them. Today's digital typefaces are most often used for offset lithography, electrophotographic printing or other processes that are not subject to the ink supply variations of letterpress, so ink traps have largely disappeared from use. This is why display cases are rarely found in the world of digital typography, whereas they were once common in letterpress printing. When digital fonts feature a "display" variation, it is to accommodate stylistic differences that may benefit type used at larger point sizes. Unfortunately, some twenty years plus into the desktop publishing revolution, few typographers with metal foundry type experience are still working (and fewer still peruse Wikipedia) so the misuse of the term "display typeface" as a synonym for "ornamental type" has become widespread.

Texts used to demonstrate typefaces

A sentence that uses all of the alphabet (a pangram), such as "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog", is often used as a design aesthetic tool to demonstrate the personality of a typeface's characters in a setting. For extended settings of typefaces graphic designers often use nonsense text (commonly referred to as "greeking"), such as lorem ipsum or Latin text such as the beginning of Cicero's in Catilinam. Greeking is used in typography to determine a typeface's "colour", or weight and style, and to demonstrate an overall typographic aesthetic prior to actual type setting.

Legal aspects

Template:Globalize/US Under United States law, typeface designs are not subject to copyright; however novel and nonobvious typeface designs are subject to protection by design patents. Digital fonts that embody a particular design are often subject to copyright as computer programs. The names of the typefaces can become trademarked. As a result of these various means of legal protection, sometimes the same typeface exists in multiple names and implementations.

Some elements of the software engines used to display fonts on computers have software patents associated with them. In particular, Apple Inc. has patented some of the hinting algorithms for TrueType, requiring open source alternatives such as FreeType to use different algorithms.

Although typeface design is not subject to copyright in the United States under the 1976 Copyright Act, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California in Adobe Systems, Inc. and Emigre, Inc. v. Southern Software, Inc. and King (No. C95-20710 RMW, N.D. Cal. Jan. 30, 1998[1]) found that there was copyright in the placement of points on a computer font's outline, i.e., because a given outline can be expressed in myriad ways, a particular selection and placement of points has sufficient originality to qualify for copyright.

Many western countries extend copyright protection to typeface designs. However, this has no impact on protection in the United States, because all of the major copyright treaties and agreements to which the U.S. is a party (such as the Berne Convention, the WIPO Copyright Treaty, and TRIPS) operate under the principle of "national treatment", under which a country is obligated to provide no greater or lesser protection to works from other countries than it provides to domestically produced works.

See also

- Calligraphy

- Computer font

- Dingbat

- Expert font

- Font family (HTML)

- Fontlab

- Font-management program

- HTML

- List of typefaces

- List of typographic features

- List of type designers

- Sans serif

- Serif

- Type design

- Type foundry

- Typography

- Typographic unit

- Unicode font

- Type Directors Club

- ATypI, Association Typographique Internationale

- Society of Typographic Aficionados

External links

- Typophile: Typefaces list

- Twenty Faces

- Fonts.com's Type 101

- An outsider's introduction to fonts

- Luc Devroye Extensive list about Typography, compiled by Luc Devroye, over 100 different categories.

- ABC typography - Introduction to the most famous typefaces

- ^ by Kristin Cullen, Layout Workbook: A Real-World Guide to Building Pages in Graphic Design, Jul 2005, pp:92