Bulgarians

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| Bulgarian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Bulgarian Orthodox including Atheist, Muslim, Roman Catholic and Protestant minorities. |

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

The Bulgarians (Bulgarian: българи or bǎlgari) are a South Slavic people generally associated with the Republic of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian language. There are Bulgarian minorities or immigrant communities in a number of other countries, too.

Ethnogenesis

Geographically Bulgaria is situated on the bridgehead between Europe and Asia. cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=8835097&dopt=AbstractPlus]</ref> From a historical angle, Bulgarians have descended from three main ethnic groups which mixed on the Balkans during the 6th - 10th century: local tribes, including the Thracians; Slavic invaders, who gave their language to the modern Bulgarians; and the Turkic-speaking Bulgars, from whom the ethnonym and the early statehood were inherited. In physical appearance, the Bulgarian population is characterized by the features of the central European anthropological type[1] with some additional influences. Genetically, modern Bulgarians are more closely related to the other Balkan populations as Macedonians, and Romanians than to the rest of the Europeans.[2][3] The ethnic contribution of the indigenous Thracian and Daco-Getic population, who had lived on the territory of modern Bulgaria and established here the Odrysian kingdom has been long debated among the scientists during the 20th century. Some recent genetic studies reveal that these peoples have indeed made a significant contribution to the genes of the modern Bulgarian population, which is however comparable, or even less than, to the contribution to other Balkan populations like Albanians and Romanians.[4]

The ancient languages of the local people had already gone extinct before the arrival of the Slavs, and their cultural influence was highly reduced due to the repeated barbaric invasions on the Balkans during the early Middle Ages by Goths, Celts, Huns, and Sarmatians, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation. The Celts also expanded down the Danube river and its tributaries in 3rd century BC. They had established a state on part of the territory of modern Bulgaria with capital Tylis, which they ruled for over a century.

The Slavs emerged from their original homeland (most commonly thought to have been in Eastern Europe) in the early 6th century, and spread to most of the eastern Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, thus forming three main branches - the West Slavs, the East Slavs and the South Slavs. The easternmost South Slavs became part of the ancestors of the modern Bulgarians, which however, are genetically clearly separated from the tight DNA cluster of the most Slavic peoples. This phenomenon is explained by “the genetic contribution of the people who lived in the region before the Slavic expansion” [5]. The frequency of the proposed Slavic Haplogroup R1a1 ranges to only 14.7% in Bulgaria.

The Bulgars were a seminomadic people thought to have spoken a Turkic language, who during the 2nd century migrated from Central Asia into the North Caucasian steppe. Between 377 and 453 they took part in the Hunnic raids on Central and Western Europe. After Attila's death in 453, and the subsequent disintegration of the Hunnic Empire, the Bulgar tribes dispersed mostly to the eastern and southeastern parts of Europe. In the late 7th century, some Bulgar tribes, led by Asparukh and others, led by Kouber, permanently settled in the Balkans, and formed the ruling classe of First Bulgarian Empire in 680-681. The Asian genetic inflow by modern Bulgarians, probably introduced from the Bulgars and other steppe's peoples who also contributed to the Bulgarian ethnogenesis, as numbers of Kumans, Pechenegs and Avars is indicated trough the limited presence of some rare alleles and haplotypes.[7][8]

On the other hand today the neighbouring Macedonians are culturally, linguistically and genetically very closely related to Bulgarians, with both of their languages being mutually intelligible. Ethnic Macedonians were identified as 'Bulgarians' by the most of the ethnographers until the middle of the 20th century. The reasons for this were manifold, particularly so because of the late emergence of a Macedonian national consciousness and religious independence, as well as the fluid and interchangeable meaning of 'ethnicity' in pre-twentieth century times. A minuscule proportion of citizens of the Republic of Macedonia continue to identify as ethnic Bulgarians, and composed about 0.5% of the population at the last census. Lately Bulgaria has maintained a policy of making the procedure as easy as possible for ethnic Macedonians who claim Bulgarian origin to claim citizenship.[9]. During the last few years in which Bulgaria saw rising economic prosperity and admission to the EU, around 60,000 citizens of Republic of Macedonia have applied for Bulgarian citizenship in this way [5][6][7][8] [9], although according to FYROM’s 2002 census, only 1,417 Macedonians claimed a Bulgarian ethnic identity.

Population

Most Bulgarians live in the Republic of Bulgaria. There are significant traditional Bulgarian minorities in Moldova and Ukraine (Bessarabian Bulgarians), as well as smaller communities in Romania (Banat Bulgarians), Serbia (the Western Outlands), Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, Albania, and Hungary. Many Bulgarians also live in the diaspora, which is formed by representatives and descendants of the old (before 1989) and new (after 1989) emigration. The old emigration was made up of some 160,000 economic and several tens of thousands of political emigrants, and was directed for the most part to the U.S., Canada, Argentina and Germany. The new emigration is estimated at some 700,000 people and can be divided into two major subcategories: permanent emigration at the beginning of the 1990s, directed mostly to the U.S., Canada, Austria, and Germany and labour emigration at the end of the 1990s, directed for the most part to Greece, Italy, the UK and Spain. Migrations to the West have been quite steady even in the late 1990s and early 21st century, as people continue moving to countries like the US, Canada and Australia. Most Bulgarians living in the US can be found in Chicago, IL. However, according to the 2000 US census most Bulgarians live in the cities of New York and Los Angeles, and the state with most Bulgarians in the US is California. The largest urban populations of Bulgarians are to be found in Sofia (1,241,000), Plovdiv (378,000), and Varna (352,000)[10]. The total number of Bulgarians thus ranges anywhere from 7 to 8 million, depending solely on the estimation used for the diaspora.

Culture

What was done in the past

Cyrillic alphabet

Medieval Bulgaria was the most important cultural centre of the Slavic people at the end of the 9th and throughout the 10th century. The two literary schools of Preslav and Ohrid developed a rich literary and cultural activity with authors of the rank of Constantine of Preslav, John Exarch, Chernorizets Hrabar, Clement and Naum of Ohrid. In the first half of the 10th century, the Cyrillic alphabet was devised in the Preslav Literary School based on the Glagolitic and the Greek alphabets. Modern versions of the alphabet are now used to write five more Slavic languages such as Belarusian, Macedonian, Russian, Serbian and Ukrainian as well as Mongolian and some other 60 languages spoken in the former Soviet Union.

Bulgaria exerted similar influence on her neighbouring countries in the mid to late 14th century, at the time of the Turnovo Literary School, with the work of Patriarch Evtimiy, Grigoriy Tsamblak, Constantine of Kostenets (Konstantin Kostenechki). Bulgarian cultural influence was especially strong in Wallachia and Moldova where the Cyrillic alphabet was used until 1860, while Slavonic was the official language of the princely chancellery and of the church until the end of 17th century.

Art and science

Bulgarians have made valuable contributions to world culture in modern times as well. Julia Kristeva and Tzvetan Todorov were among the most influential European philosophers in the second half of the 20th century. Nicolai Ghiaurov, Boris Christoff, Raina Kabaivanska and Ghena Dimitrova made a precious contribution to opera singing with Ghiaurov and Christoff being two of the greatest bassos in the post-war period. The artist Christo is among the most famous representatives of environmental art with projects such as the Wrapped Reichstag.

Bulgarians in the diaspora have also been active. American scientists and inventors of Bulgarian descent include John Atanasoff, Peter Petroff, and Assen Jordanoff. Bulgarian-American Stephane Groueff wrote the celebrated book "Manhattan Project", about the making of the first atomic bomb and also penned "Crown of Thorns", a biography of Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria.

Sport

In sports, Hristo Stoichkov was one of the best soccer players in the second half of the 20th century, having played with the national team and FC Barcelona. He received a number of awards and was the joint top scorer at the 1994 World Cup. High-jumper Stefka Kostadinova was one of the top ten female athletes of the last century and holds one of the oldest unbroken world records in athletics. In the beginning of the 20th century Bulgaria was famous for two of the best wrestlers in the world - Dan Kolov and Nikola Petroff.

Language

Bulgarians speak a Southern Slavic language which is to some point similar to Serbo-Croatian and is often (mostly words, not sentences) mutually intelligible with it. The Bulgarian language is also, to some degree, mutually intelligible with Russian on account of the influence which Russia has had on the development of Modern Bulgaria since 1878, as well as the earlier effect of Old Bulgarian on the development of Old Russian. Although related, Bulgarian and the Western and Eastern Slavic languages are not mutually intelligible.

Bulgarian demonstrates several linguistic developments that set it apart from other Slavic languages. These are shared with Romanian, Albanian and Greek (see Balkan linguistic union). Until 1878 Bulgarian was influenced lexically by medieval and modern Greek, and to a much lesser extent, by Turkish. More recently, the language has borrowed many words from Russian, German, French and English.

Some members of the diaspora do not speak the Bulgarian language (mostly representatives of the old emigration in the U.S., Canada and Argentina) but are still considered Bulgarians by ethnic origin or descent.

The majority of the Bulgarian linguists, as well as international ones, consider the officialized since 1944 Macedonian language a local variation of Bulgarian, although the linguistic consensus suggests that a language is a language if its speakers define it as such.

The Bulgarian language is written in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Name system

There are several different layers of Bulgarian names. The vast majority of them have either Christian (names like Lazar, Ivan, Anna, Maria, Ekaterina) or Slavic origin (Vladimir, Svetoslav, Velislava). After the Liberation in 1878, the names of historical Bulgar rulers like Asparuh, Krum, Kubrat and Tervel were resurrected. The old Bulgar name Boris has spread from Bulgaria to a number of countries in the world with Russian tsar Boris Godunov and German tennis player Boris Becker being two of the examples of its use.

Most Bulgarian male surnames have an -ov surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ов). This is sometimes transcribed as -off (John Atanasov — John Atanasoff, but more often as -ov e.g. Hristo Stoichkov). The -ov suffix is the Slavic gender-agreeing suffix, thus Ivanov (Bulgarian: Иванов) really means "Ivan's". Bulgarian middle names use the gender-agreeing suffix as well, thus the middle name of Nikola's son becomes Nikolov, and the middle name of Ivan's son becomes Ivanov. Since names in Bulgarian are gender-based, Bulgarian women have the -ova surname suffix (Cyrillic: -овa), for example, Maria Ivanova. The plural form of Bulgarian names ends in -ovi (Cyrillic: -ови), for example the Ivanovi family (Иванови).

Other common Bulgarian male surnames have the -ev surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ев), for example Stoev, Ganchev, Peev, and so on. The female surname in this case would have the -eva surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ева), for example: Galina Stoeva. The last name of the entire family then would have the plural form of -evi (Cyrillic: -еви), for example: the Stoevi family (Стоеви).

Another typical Bulgarian surname suffix, though much less common, is -ski. This surname ending also gets an –a when the bearer of the name is female (Smirnenski becomes Smirnenska). The plural form of the surname suffix -ski is still -ski, e.g. the Smirnenski family (Bulgarian: Смирненски).

The surname suffix -ich can be found sometimes, primarily among Catholic Bulgarians. The ending –in (female -ina) also appears sometimes, though rather seldom. It used to be given to the child of an unmarried woman (for example the son of Kuna will get the surname Kunin and the son of Gana – Ganin). The surname ending –ich does not get an additional –a if the bearer of the name is female.

Religion

Most Bulgarians are at least nominally members of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church founded in 870 AD (autocephalous since 927 AD). The Bulgarian Orthodox Church is the independent national church of Bulgaria like the other national branches of Eastern Orthodoxy and is considered an inseparable element of Bulgarian national consciousness. The church has been abolished twice during the periods of Byzantine (1018—1185) and Ottoman (1396—1878) domination but was revived every time as a symbol of Bulgarian statehood. In 2001, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church had a total of 6,552,000 members in Bulgaria (82.6% of the population) and between one and two million members in the diaspora. The problem with the allegiance of the Orthodox Bulgarian minorities in Serbia, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine has not yet been settled and Bulgarians in those countries still hold allegiance to the respective national orthodox churches.

Despite the position of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church as a unifying symbol for all Bulgarians, smaller or larger groups of Bulgarians have converted to other faiths or denominations through the course of time. In the 16th and the 17th century Roman Catholic missionaries converted the Bulgarian Paulicians in the districts of Plovdiv and Svishtov to Roman Catholicism. Nowadays there are some 40,000 Catholic Bulgarians in Bulgaria and additional 10,000 in Banat in Romania. The Catholic Bulgarians of the Banat are also descendants of Paulicians who fled to Banat at the end of the 17th century after an unsuccessful uprising against the Ottomans.

Protestantism was introduced in Bulgaria by missionaries from the United States in 1857. Missionary work continued throughout the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. In 2001, there were some 25,000 Protestant Bulgarians in Bulgaria.

Between 15th and 20th century, during the Ottoman rule, a large number of Orthodox Bulgarians converted to Islam. Their descendants now form the second largest religious congregation in Bulgaria. In 2001, there were 131,000 Muslim Bulgarians or Pomaks in Bulgaria in the Rhodope region, as well as some villages in the Teteven region in Central North Bulgaria. Their origins are obscure,[11] but they are generally believed to be Bulgarians who converted to Islam during the period of Ottoman rule in the Balkans.[12]

.

Symbols

The national symbols of the Bulgarians are the Flag of Bulgaria and the Coat of Arms of Bulgaria.

The national flag of Bulgaria is a rectangle with three colors: white, green, and red, positioned horizontally top to bottom. The color fields are of same form and equal size.

The Coat of Arms of Bulgaria is a state symbol of the sovereignty and independence of the Bulgarian people and state. It represents a crowned rampant golden lion on a dark red background with the shape of a shield. Above the shield there is a crown modeled after the crowns of the kings of the Second Bulgarian Empire, with five crosses and an additional cross on top. Two crowned rampant golden lions hold the shield from both sides, facing it. They stand upon two crossed oak branches with acorns, which symbolize the power and the longevity of the Bulgarian state. Under the shield, there is a white band lined with the three national colors. The band is placed across the ends of the branches and the phrase "Unity Makes Strength" is inscribed on it.

Both the Bulgarian flag and the Coat of Arms are also used as symbols of various Bulgarian organisations, political parties and institutions.

Bulgarians. Faces through history

-

Khan Omurtag (815-831), warrior and builder

-

Saint Knyaz Boris I (852–889), converted the Bulgarians into Christianity

-

A fresco from Boyana Church near Sofia depicting Desislava, a church patron (1259)

-

Bulgarian women from the period of the Ottoman Empire rule (16th century)

-

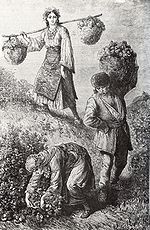

Bulgarian peasants with Bulgarian merchant and his son in the late Ottoman Empire, 1860ies

-

Knjaz Alexander Batemberg, first ruler of modern Bulgaria

-

Yordan Radichkov (1929-2004), writer

-

Valya Balkanska, folk music singer

-

Veselin Topalov, former world chess champion

Population data

1This total population estimate includes only ethnic Bulgarians born in Bulgaria and their descendants abroad.

² Results according to the latest available census held in the country in question and year of the census: Bulgaria (Census 2001), Canada (2001), Kazakhstan 1999, Russia (2002), Serbia and Montenegro (2002), Ukraine (2001), USA (2002), Slovenia (2002).

³ Official number of citizens of the Republic of Bulgaria in Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy and Spain. The numbers do not include Bulgarian-speaking people without Bulgarian citizenship, except for Spain.

4 Estimates of the Agency for Bulgarians Abroad for the numbers of ethnic Bulgarians living for the country in question based on data from the Bulgarian Border Police, the Bulgarian Ministry of Labour and reports from immigrant associations. The numbers include legal immigrants, illegal immigrants, students and other individuals permanently residing in the country in question as of 2004.

5 Bulgarian embassy, Dublin statistics

References

- ^ HLA-DRB1, DQA1, DQB1 DNA polymorphism in the Bulgarian population.Division of Clinical and Transplantation Immunology, Medical University, Sofia, Bulgaria.

- ^ HLA polymorphism in Bulgarians defined by high-resolution typing methods in comparison with other populations.

- ^ Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language

- ^ Paleo-MtDNA Analysis and population genetic aspects of old Thracian population from South-Eastern Romania

- ^ Anthropological Evidence and the Fallmerayer Thesis

- ^ The British researcher of the Balkans H. N. Brailsford in his book "Macedonia: its races and their future" started the chapter about the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising in Macedonia with the words: "The moment for which the Bulgarian population had been preparing for ten years arrived on the festival of the Prophet Elias — the evening of Sunday, August the 2nd, 1903." H. N. Brailsford, "Macedonia: Its Races and Their Future", Methuen & Co., London, 1906, part V. The Bulgarian movement, chapter 11. The General Rising of 1903 in Monastir, p. 148, online publication here, retrieved on October 8, 2007.

- ^ Five polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein B gene in healthy Bulgarians. Human Biology, Feb 2003.[1]

- ^ GENOTYPE AND ALLELIC FREQUENCIES OF A Taq1 POLYMORPHISM IN THE 3’-UTR OF THE IL-12 p40 GENE IN BULGARIANS. L. Miteva, S. Stanilova

- ^ Shkodrova, Albena, 2005. Bulgaria's Warm Embrace. Institute for War and Peace Reporting

- ^ Главна Дирекция Гражданска Регистрация и Административно Обслужване

- ^ F. De Jong, "The Muslim Minority in Western Thrace", (1980), p. 95

- ^ A Country Study: Bulgaria, "Pomaks", (1992)

- ^ Contemporary Macedonian academician Ivan Katardzhiev, director of the Historical Sciences section in the Department of Social Sciences in the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, states in "Мега интервjу. Иван Катарџиев, академик. Верувам во националниот имунитет на Македонецот" (in Macedonian): "Форум - Дали навистина Делчев се изјаснувал како Бугарин и зошто? Катарџиев - Ваквите прашања стојат. Сите наши луѓе се именувале како „Бугари“..." In English: "Interview. Academician Ivan Katardzhiev. I believe in Macedonian national immunity", www.forum.com.mk magazine, retrieved on October 8, 2007: "Forum - Whether Gotse Delchev really defined himself as Bulgarian and why? Katardzhiev - Such questions exist. All our people named themselves as "Bulgarians"..." Ph. D. Zoran Todorovski, director of the Macedonian State Archive, asserts about Macedonian inteligentsia and revolutionaries in the beginning of the 20th century that "Сите се декларирале како Бугари..." (in Macedonian; in English "All of them declared themselves as Bulgarians..."), interview for www.tribune.eu.com, published on June 27, 2005, retrieved on October 8, 2007.