Ulcerative colitis

| Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Ulcerative colitis (Colitis ulcerosa, UC) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Ulcerative colitis is a form of colitis, a disease of the intestine, specifically the large intestine or colon, that includes characteristic ulcers, or open sores, in the colon. The main symptom of active disease is usually diarrhea mixed with blood, of gradual onset. Ulcerative colitis is, however, a systemic disease that affects many parts of the body outside the intestine. Because of the name, IBD is often confused with irritable bowel syndrome ("IBS"), a troublesome, but much less serious condition. Ulcerative colitis has similarities to Crohn's disease, another form of IBD. Ulcerative colitis is an intermittent disease, with periods of exacerbated symptoms, and periods that are relatively symptom-free. Although the symptoms of ulcerative colitis can sometimes diminish on their own, the disease usually requires treatment to go into remission.

Ulcerative colitis is a rare disease, with an incidence of about one person per 10,000 in North America. The disease tends to be more common in northern areas. Although ulcerative colitis has no known cause, there is a presumed genetic component to susceptibility. The disease may be triggered in a susceptible person by environmental factors. Although dietary modification may reduce the discomfort of a person with the disease, ulcerative colitis is not thought to be caused by dietary factors. Although ulcerative colitis is treated as though it were an autoimmune disease, there is no consensus that it is such. Treatment is with anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppression (suppressing the immune system), and biological therapy targeting specific components of the immune response. Colectomy (partial or total removal of the large bowel through surgery) is occasionally necessary, and is considered to be a cure for the disease.

Causes

While the cause of ulcerative colitis is unknown, several, possibly interrelated, causes have been suggested.

Genetic factors

A genetic component to the etiology of ulcerative colitis can be hypothesized based on the following:[1]

- Aggregation of ulcerative colitis in families.

- Identical twin concordance rate of 10% and dizygotic twin concordance rate of 3%[2]

- Ethnic differences in incidence

- Genetic markers and linkages

There are 12 regions of the genome which may be linked to ulcerative colitis. This includes chromosomes 16, 12, 6, 14, 5, 19, 1, 16, and 3 in the order of their discovery.[3] However, none of these loci has been consistently shown to be at fault, suggesting that the disorder arises from the combination of multiple genes. For example, chromosome band 1p36 is one such region thought to be linked to inflammatory bowel disease.[4] Some of the putative regions encode transporter proteins such as OCTN1 and OCTN2. Other potential regions involve cell scaffolding proteins such as the MAGUK family. There are even HLA associations which may be at work. In fact, this linkage on chromosome 6 may be the most convincing and consistent of the genetic candidates.[3]

Multiple autoimmune disorders have been recorded with the neurovisceral and cutaneous genetic porphyrias including ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, celiac disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, systemic and discoid lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, scleroderma, Sjogren's disease and scleritis. Physicians should be on high alert for porphyrias in families with autoimmune disorders and care must be taken with potential porphyrinogenic drugs, including sulfasalazine.

Environmental factors

Many hypotheses have been raised for environmental contributants to the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. They include the following:

- Diet: as the colon is exposed to many different dietary substances which may encourage inflammation, dietary factors have been hypothesized to play a role in the pathogenesis of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. There have been few studies to investigate such an association, but one study showed no association of refined sugar on the prevalence of ulcerative colitis.[5]

- Diet: A diet low in fermentable dietary fiber may affect ulcerative colitis incidence.

- Breastfeeding: There have been conflicting reports of the protection of breastfeeding in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. One Italian study showed a potential protective effect.[6]

- Other childhood exposures, or infections[citation needed]

Autoimmune disease

Some sources list ulcerative colitis as an autoimmune disease, a disease in which the immune system malfunctions, attacking some part of the body. As discussed above, ulcerative colitis is a systemic disease that affects many areas of the body outside the digestive system. Surgical removal of the large intestine often cures the disease, including the manifestations outside the digestive system.[7] This suggests that the cause of the disease is in the colon itself, and not in the immune system or some other part of the body.

Alternative theories

Levels of sulfate-reducing bacteria tend to be higher in persons with ulcerative colitis. This could mean that there are higher levels of hydrogen sulfide in the intestine. An alternative theory suggests that the symptoms of the disease may be caused by toxic effects of the hydrogen sulfide on the cells lining the intestine.[8][9] It may be caused occlusions in the capillaries of the subepithelial linings, degenerated fibers beneath the mucosa and infiltration of the lamina propria with plasma cells

Epidemiology

The incidence of ulcerative colitis in North America is 10-12 cases per 100,000, with a peak incidence of ulcerative colitis occurring between the ages of 15 and 25. There is thought to be a bimodal distribution in age of onset, with a second peak in incidence occurring in the 6th decade of life. The disease affects females more than males.[10]

The geographic distribution of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease is similar worldwide,[11] with highest incidences in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia. Higher incidences are seen in northern locations compared to southern locations in Europe and the United States.[12]

As with Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis is thought to occur more commonly among Ashkenazi Jewish people than non-Jewish people.

Clinical presentation

GI symptoms

The clinical presentation[10] of ulcerative colitis depends on the extent of the disease process. Patients usually present with diarrhea mixed with blood and mucus, of gradual onset. They also may have signs of weight loss, and blood on rectal examination. The disease is usually accompanied with different degrees of abdominal pain, from mild discomfort to severely painful cramps.

Ulcerative colitis is a systemic disease that affects many parts of the body. Sometimes the extra-intestinal manifestations of the disease are the initial signs, such as painful, arthritic knees in a teenager. It is, however, unlikely that the disease will be correctly diagnosed until the onset of the intestinal manifestations.

Extent of involvement

Ulcerative colitis is normally continuous from the rectum up the colon. The disease is classified by the extent of involvement, depending on how far up the colon the disease extends:

- Distal colitis, potentially treatable with enemas:[7]

- Proctitis: Involvement limited to the rectum.

- Proctosigmoiditis: Involvement of the rectosigmoid colon, the portion of the colon adjacent to the rectum.

- Left-sided colitis: Involvement of the descending colon, which runs along the patient's left side, up to the splenic flexure and the beginning of the transverse colon.

- Extensive colitis, inflammation extending beyond the reach of enemas:

- Pancolitis: Involvement of the entire colon, extending from the rectum to the cecum, beyond which the small intestine begins.

Severity of disease

In addition to the extent of involvement, UC patients may also be characterized by the severity of their disease.[7]

- Mild disease correlates with fewer than four stools daily, with or without blood, no systemic signs of toxicity, and a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). There may be mild abdominal pain or cramping. Patients may believe they are constipated when in fact they are experiencing tenesmus, which is a constant feeling of the need to empty the bowel accompanied by involuntary straining efforts, pain, and cramping with little or no fecal output. Rectal pain is uncommon.

- Moderate disease correlates with more than four stools daily, but with minimal signs of toxicity. Patients may display anemia (not requiring transfusions), moderate abdominal pain, and low grade fever, 38 to 39 °C (99.5 to 102.2 °F).

- Severe disease, correlates with more than six bloody stools a day, and evidence of toxicity as demonstrated by fever, tachycardia, anemia or an elevated ESR.

- Fulminant disease correlates with more than ten bowel movements daily, continuous bleeding, toxicity, abdominal tenderness and distension, blood transfusion requirement and colonic dilation (expansion). Patients in this category may have inflammation extending beyond just the mucosal layer, causing impaired colonic motility and leading to toxic megacolon. If the serous membrane is involved, colonic perforation may ensue. Unless treated, fulminant disease will soon lead to death.

Extraintestinal features

As ulcerative colitis is a systemic disease, patients may present with symptoms and complications outside the colon. These include the following:

- aphthous ulcers of the mouth

- Ophthalmic (involving the eyes):

- Iritis or uveitis, which is inflammation of the iris

- Episcleritis

- Musculoskeletal:

- Seronegative arthritis, which can be a large-joint oligoarthritis (affecting one or two joints), or may affect many small joints of the hands and feet

- Ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis of the spine

- Sacroiliitis, arthritis of the lower spine

- Cutaneous (related to the skin):

- Erythema nodosum, which is a panniculitis, or inflammation of subcutaneous tissue involving the lower extremities

- Pyoderma gangrenosum, which is a painful ulcerating lesion involving the skin

- Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- clubbing, a deformity of the ends of the fingers

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis, or inflammation of the bile ducts

Similar conditions

The following conditions may present in a similar manner as ulcerative colitis, and should be excluded:

- Crohn's disease

- Infectious colitis, which is typically detected on stool cultures

- Pseudomembranous colitis, or Clostridium difficile-associated colitis, bacterial upsets often seen following administration of antibiotics

- Ischemic colitis, inadequate blood supply to the intestine, which typically affects the elderly

- Radiation colitis in patients with previous pelvic radiotherapy

- Chemical colitis resulting from introduction of harsh chemicals into the colon from an enema or other procedure.

Comparison to Crohn's Disease

The most common disease that mimics the symptoms of ulcerative colitis is Crohn's disease, as both are inflammatory bowel diseases that can affect the colon with similar symptoms. It is important to differentiate these diseases, since the course of the diseases and treatments may be different. In some cases, however, it may not be possible to tell the difference, in which case the disease is classified as indeterminate colitis.

| Crohn's Disease | Ulcerative Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Involves terminal ileum? | Commonly | Seldom |

| Involves colon? | Usually | Always |

| Involves rectum? | Seldom | Usually |

| Peri-anal involvement? | Commonly | Seldom |

| Bile duct involvement? | Not associated | Higher rate of Primary sclerosing cholangitis[13] |

| Distribution of Disease | Patchy areas of inflammation | Continuous area of inflammation |

| Endoscopy | Linear and serpiginous (snake-like) ulcers | Continuous ulcer |

| Depth of inflammation | May be transmural, deep into tissues | Shallow, mucosal |

| Fistulae, abnormal passageways between organs | Commonly | Seldom |

| Biopsy | Can have granulomata | Crypt abscesses and cryptitis |

| Surgical cure? | Often returns following removal of affected part | Usually cured by removal of colon, can be followed by pouchitis |

| Smoking | Higher risk for smokers | Lower risk for smokers |

| Autoimmune disease? | Generally regarded as an autoimmune disease | No consensus |

| Cancer risk? | Lower than ulcerative colitis | Higher than Crohn's |

Diagnosis and workup

General

The initial diagnostic workup for ulcerative colitis includes the following:[14][7]

- A complete blood count is done to check for anemia; thrombocytosis, a high platelet count, is occasionally seen

- Electrolyte studies and renal function tests are done, as chronic diarrhea may be associated with hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia and pre-renal failure.

- Liver function tests are performed to screen for bile duct involvement: primary sclerosing cholangitis.

- X-ray

- Urinalysis

- Stool culture, to rule out parasites and infectious causes.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be measured, with an elevated sedimentation rate indicating that an inflammatory process is present.

- C-reactive protein can be measured, with an elevated level being another indication of inflammation.

Although ulcerative colitis is a disease of unknown causation, inquiry should be made as to unusual factors believed to trigger the disease.[7] Factors may include: recent cessation of tobacco smoking; recent administration of large doses of iron or vitamin B6; hydrogen peroxide in enemas or other procedures.

Endoscopic

The best test for diagnosis of ulcerative colitis remains endoscopy. Full colonoscopy to the cecum and entry into the terminal ileum is attempted only if diagnosis of UC is unclear. Otherwise, a flexible sigmoidoscopy is sufficient to support the diagnosis. The physician may elect to limit the extent of the exam if severe colitis is encountered to minimize the risk of perforation of the colon. Endoscopic findings in ulcerative colitis include the following:

- Loss of the vascular appearance of the colon

- Erythema (or redness of the mucosa) and friability of the mucosa

- Superficial ulceration, which may be confluent, and

- Pseudopolyps.

Ulcerative colitis is usually continuous from the rectum, with the rectum almost universally being involved. There is rarely peri-anal disease, but cases have been reported. The degree of involvement endoscopically ranges from proctitis or inflammation of the rectum, to left sided colitis, to pancolitis, which is inflammation involving the ascending colon.

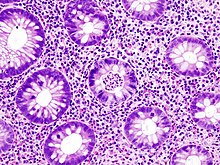

Histologic

Biopsies of the mucosa are taken to definitively diagnose UC and differentiate it from Crohn's disease, which is managed differently clinically. Microbiological samples are typically taken at the time of endoscopy. The pathology in ulcerative colitis typically involves distortion of crypt architecture, inflammation of crypts (cryptitis), frank crypt abscesses, and hemorrhage or inflammatory cells in the lamina propria. In cases where the clinical picture is unclear, the histomorphologic analysis often plays a pivotal role in determining the management.

Course and complications

Progression or remission

Patients with ulcerative colitis usually have an intermittent course, with periods of disease inactivity alternating with "flares" of disease. Patients with proctitis or left-sided colitis usually have a more benign course: only 15% progress proximally with their disease, and up to 20% can have sustained remission in the absence of any therapy. Patients with more extensive disease are less likely to sustain remission, but the rate of remission is independent of the severity of disease.

Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer

There is a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis after 10 years if involvement is beyond the splenic flexure. Those with only proctitis or rectosigmoiditis usually have no increased risk.[7] It is recommended that patients have screening colonoscopies with random biopsies to look for dysplasia after eight years of disease activity[15]

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Ulcerative colitis has a significant association with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a progressive inflammatory disorder of small and large bile ducts. As many as 5% of patients with ulcerative colitis may progress to develop primary sclerosing cholangitis.[16]

Mortality

The effect of ulcerative colitis on mortality is unclear, but it is thought that the disease primarily affects quality of life, and not lifespan.

Treatment

Standard treatment for ulcerative colitis depends on extent of involvement and disease severity. The goal is to induce remission initially with medications, followed by the administration of maintenance medications to prevent a relapse of the disease. The concept of induction of remission and maintenance of remission is very important. The medications used to induce and maintain a remission somewhat overlap, but the treatments are different. Physicians first direct treatment to inducing a remission which involves relief of symptoms and mucosal healing of the lining of the colon and then longer term treatment to maintan the remission.

Drugs used

Aminosalicylates

Sulfasalazine has been a major agent in the therapy of mild to moderate UC for over 50 years. In 1977 Mastan S.Kalsi et al determined that 5-aminosalicyclic acid (5-ASA and mesalazine) was the therapeutically active compound in sulfasalazine. Since then many 5-ASA compounds have been developed with the aim of maintaining efficacy but reducing the common side effects associated with the sulfapyridine moiety in sulfasalazine.[17]

- Mesalazine, also known as 5-aminosalicylic acid, mesalamine, or 5-ASA. Brand name formulations include Asacol, Pentasa, Mezavant, Lialda, and Salofalk.

- Sulfasalazine, also known as Azulfidine.

- Balsalazide - Disodium, also known as Colazal.

- Olsalazine, also known as Dipentum.

Corticosteroids

- Cortisone

- Prednisone

- Prednisolone

- Hydrocortisone

- Methylprednisolone

- Beclometasone

- Budesonide - under the brand name of Entocort

Immunosuppressive drugs

- Mercaptopurine, also known as 6-Mercaptopurine, 6-MP and Purinethol.

- Azathioprine, also known as Imuran, Azasan or Azamun, which metabolises to 6-MP.

- Methotrexate, which inhibits folic acid

- Tacrolimus

Surgery

Unlike Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis can generally be cured by surgical removal of the large intestine. This procedure is necessary in the event of: exsanguinating hemorrhage, frank perforation or documented or strongly suspected carcinoma. Surgery is also indicated for patients with severe colitis or toxic megacolon. Patients with symptoms that are disabling and do not respond to drugs may wish to consider whether surgery would improve the quality of life.

Ulcerative colitis is a disease that affects many parts of the body outside the intestinal tract. In rare cases the extra-intestinal manifestations of the disease may require removal of the colon.[7]

Alternative treatments

Smoking

Unlike Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis has a lesser prevalence in smokers than non-smokers.[18]

Dietary modification

Dietary modification may reduce the symptoms of the disease.

- Lactose intolerance is noted in many ulcerative colitis patients. Those with suspicious symptoms should get a lactose breath hydrogen test.

- Patients with abdominal cramping or diarrhea may find relief or a reduction in symptoms by avoiding fresh fruits and vegetables, caffeine, carbonated drinks and sorbitol-containing foods.

- Many dietary approaches have purported to treat UC, including the Elaine Gottschall's specific carbohydrate diet and the "anti-fungal diet" (Holland/Kaufmann).

- The use of elemental and semi-elemental formula has been successful in pediatric patients.

Fats and oils

- Fish oil. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), derived from fish oil. This is an Eicosanoid that inhibits leukotriene activity. It is effective as an adjunct therapy. There is no recommended dosage for ulcerative colitis. Dosages of EPA of 180 to 1500 mg/day are recommended for other conditions. [1]

- Short chain fatty acid (butyrate) enema. The colon utilizes butyrate from the contents of the intestine as an energy source. The amount of butyrate available decreases toward the rectum. Inadequate butyrate levels in the lower intestine have been suggested as a contributing factor for the disease. This might be addressed through butyrate enemas. The results however are not conclusive.

Herbals

- Herbal medications are used by patients with ulcerative colitis. Compounds that contain sulphydryl may have an effect in ulcerative colitis (under a similar hypothesis that the sulpha moiety of sulfasalazine may have activity in addition to the active 5-ASA component).[19] One randomized control trial evaluated the over-the-counter medication methionine-methyl sulphonium chloride (abbreviated MMSC, but more commonly referred to as Vitamin U) and found a significant decreased rate of relapse when the medication was used in conjunction with oral sulfasalazine.[20]

Bacterial recolonization

- Probiotics may have benefit. One study which looked at a probiotic known as VSL#3 has shown promise for people with ulcerative colitis.[21]

- Fecal bacteriotherapy involves the infusion of human probiotics through fecal enemas.[22] It suggests that the cause of ulcerative colitis may be a previous infection by a still unknown pathogen. This initial infection resolves itself naturally, but somehow causes an imbalance in the colonic bacterial flora, leading to a cycle of inflammation which can be broken by "recolonizing" the colon with bacteria from a healthy bowel. There have been several reported cases of patients who have remained in remission for up to 13 years.[23]

Intestinal parasites

Inflammatory bowel disease is less common in the developing world. Some have suggested that this may be because intestinal parasites are more common in underdeveloped countries. Some parasites are able to reduce the immune response of the intestine, an adaptation that helps the parasite colonize the intestine. The decrease in immune response could reduce or eliminate the inflammatory bowel disease

Helminthic therapy using the whipworm Trichuris suis has been shown in a randomized control trial from Iowa to show benefit in patients with ulcerative colitis. The therapy tests the hygiene hypothesis which argues that the absence of helminths in the colons of patients in the developed world may lead to inflammation. Both helminthic therapy and fecal bacteriotherapy induce a characteristic Th2 white cell response in the diseased areas, which is somewhat paradoxical given that ulcerative colitis immunology was thought to classically involve Th2 overproduction[24]

Nicotine It has been shown that smokers on a dose-based schedule have their ulcerative colitis symptoms effectively reduced by cigarettes. The effect disappears if the user quits.

Ongoing research

Recent evidence from the ACT-1 trial suggests that infliximab may have a greater role in inducing and maintaining disease remission.

An increased amount of colonic sulfate-reducing bacteria has been observed in some patients with ulcerative colitis, resulting in higher concentrations of the toxic gas hydrogen sulfide. The role of hydrogen sulfide in pathogenesis is unclear. It has been suggested that the protective benefit of smoking that some patients report is due to hydrogen cyanide from cigarette smoke reacting with hydrogen sulfide to produce the nontoxic isothiocyanate. Another unrelated study suggested sulphur contained in red meats and alcohol may lead to an increased risk of relapse for patients in remission[8]

There is much research currently being done to elucidate further genetic markers in ulcerative colitis. Linkage with Human Leukocyte Antigen B-27, associated with other autoimmune diseases, has been proposed.

Low dose naltrexone is under study for treatment of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

See also

External links

- General Information

- Ulcerative Colitis - the possible causes, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

- Information on Ulcerative Colitis - including diet and supplements

- Resourses for the treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

- Ulcerative Colitis clinical trials and findings from current research

- Living with Ulcerative Colitis

- blog for people suffering from Colitis

Organizations

- Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America

- European Federation of Crohns and Colitis Associations has member associations in most European countries.

- Children and youngster group within the European Federation of Crohns and Colitis Assiciations

- National Association for Colitis and Crohn's disease UK

- Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of Canada

References

- ^ Orholm M, Binder V, Sorensen TI, Rasmussen LP, Kyvik KO. Concordance of inflammatory bowel disease among Danish twins. Results of a nationwide study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000;35:1075-81. PMID 11099061.

- ^ Tysk C, Lindberg E, Jarnerot G, Floderus-Myrhed B (1988). ""Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in an unselected population of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. A study of heritability and the influence of smoking". Gut. 29: 990–996.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Baumgart DC, Carding SF (May 2007). ""Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology"". Lancet. 369 (9573). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|Pages=ignored (|pages=suggested) (help) - ^ Cho JH, Nicolae DL, Ramos R, Fields CT, Rabenau K, Corradino S, Brant SR, Espinosa R, LeBeau M, Hanauer SB, Bodzin J, Bonen DK. Linkage and linkage disequilibrium in chromosome band 1p36 in American Chaldeans with inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:1425-32. Fulltext. PMID 10814724.

- ^ Jarnerot G, Jarnmark I, Nilsson K. Consumption of refined sugar by patients with Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, or irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1983;18:999-1002. PMID 6673083.

- ^ Corrao G, Tragnone A, Caprilli R, Trallori G, Papi C, Andreoli A, Di Paolo M, Riegler G, Rigo GP, Ferrau O, Mansi C, Ingrosso M, Valpiani D. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease attributable to smoking, oral contraception and breastfeeding in Italy: a nationwide case-control study. Cooperative Investigators of the Italian Group for the Study of the Colon and the Rectum (GISC). Int J Epidemiol 1998;27:397-404. PMID 9698126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ulcerative Colitis Practice Guidelines in Adults, Am. Coll. Gastroenterology, 2004. PDF

- ^ a b Roediger WE, Moore J, Babidge W. Colonic sulfide in pathogenesis and treatment of ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:1571-9. PMID 9286219.

- ^ Levine J, Ellis CJ, Furne JK, Springfield J, Levitt MD. Fecal hydrogen sulfide production in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:83-7. PMID 9448181.

- ^ a b Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 1996;334:841-848. PMID 8596552.

- ^ Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2002;347:417-424. PMID 12167685.

- ^ Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, Fear N, Price A, Carpenter L, van Blankenstein M. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Gut 1996;39:690-7. PMID 9014768.

- ^ Broome U, Bergquist A. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and colon cancer. Semin Liver Dis 2006 February;26(1):31-41. PMID 16496231.

- ^ Al-Ataie MB, Shinoy VN. eMedicine: Ulcerative colitis. Fulltext.

- ^ Leighton JA, Shen B, Baron TH, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan JV, Faigel DO, Gan SI, Hirota WK, Lichtenstein D, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, VanGuilder T, Fanelli RD; Standards of Practice Committee, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. ASGE guideline: endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:558-65. PMID 16564852.

- ^ Olsson R, Danielsson A, Jarnerot G, Lindstrom E, Loof L, Rolny P, Ryden BO, Tysk C, Wallerstedt S. Prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1991;100(5 Pt 1):1319-23. PMID 2013375.

- ^ S. Kane (2006). "Asacol - A Review Focusing on Ulcerative Colitis".

- ^ Calkins BM. A meta-analysis of the role of smoking in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:1841-54. PMID 2598752.

- ^ Brzezinski A, Rankin G, Seidner D, Lashner B. "Use of old and new oral 5-aminosalicylic acid formulations in inflammatory bowel disease". Cleve Clin J Med. 62 (5): 317–23. PMID 7586488.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Salim A (1992). "Role of sulphydryl-containing agents in the management of recurrent attacks of ulcerative colitis. A new approach". Pharmacology. 45 (6): 307–18. PMID 1362613.

- ^ Bibiloni R, Fedorak RN, Tannock GW, Madsen KL, Gionchetti P, Campieri M, De Simone C, Sartor RB. VSL#3 probiotic-mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2005 Jul;100(7):1539-46. PMID 15984978.VSL#3 company site

- ^ Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis SM, Surace R, Ashman O, Siarakas S. Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:475-83. PMID 15220681.Fulltext(PDF)

- ^ Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis S, Surace R, Ashman O. Treatment of ulcerative colitis using fecal bacteriotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:42-7. PMID 12811208.Fulltext(PDF)

- ^ Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF Jr, Thompson RA, Weinstock JV. Trichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2005;128:825-32. PMID 15825065.