Magic Johnson

Earvin "Magic" Johnson, Jr. (born August 14 1959) is a retired American basketball player who played for the Los Angeles Lakers of the National Basketball Association (NBA). After winning a championship at both the high school and college level, Johnson was selected first overall in the 1979 NBA Draft by the Lakers. Johnson established his reputation as a great player after winning a championship in his first season, and the Lakers went on to win a total of five championships during the 1980s. Johnson retired abruptly in 1991 after announcing that he had HIV, but he returned to win the MVP of 1992 All-Star Game. He retired again for four years after protests from his fellow players, but he returned in 1996 to play 32 games for the Lakers, before retiring for the second and final time.

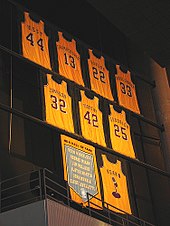

Johnson's career achievements include five NBA championships, three Most Valuable Player Awards and three Finals Most Valuable Player Awards. He also played in nine NBA Finals series, 12 All-Star games, and was voted into 10 All-NBA First and Second Teams. He led the league in regular season assists four times, and he is the NBA's all-time leader in assists per game with an average of 11.2 per game.[1] Johnson was also a member of the "Dream Team" U.S. basketball team which won the Olympic gold medal in 1992.

For his accomplishments, Johnson was honored as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996, and enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2002.[2] He was also rated the the greatest NBA point guard of all time by ESPN in 2007.[3] His friendship and rivalry with Boston Celtics star Larry Bird—based on regular games at championship level between the Lakers and Celtics—were well-documented. Since his retirement, he has been an advocate for HIV/AIDS prevention and safe sex,[4] as well as a philanthropist.[5]

Professional biography

Early years

Earvin Johnson Jr. was the sixth of ten children born to Earvin Sr., a General Motors assembly worker, and Christine, a school custodian.[6] Johnson grew up in Lansing, Michigan, and came to love basketball as a youngster, idolizing players such as Earl Monroe and Marques Haynes.[7] "I practiced all day," he later said. "I dribbled to the store with my right hand and back with my left. Then I slept with my basketball."[4]

Johnson was first nicknamed "Magic" as a 15-year-old sophomore playing for Lansing's Everett High School, when he recorded a triple-double of 36 points, 18 rebounds and 16 assists.[8] After the game, Fred Stabley Jr., a sports writer for the Lansing State Journal, nicknamed him "Magic",[9] despite Johnson's Christian mother thinking that the name was sacriligeous.[4] In the summer before his senior year, Johnson's best friend Reggie Chastaine was killed in a car accident, which Johnson said was "devastating".[10] During his final high school season, Johnson led Lansing Everett to a 27–1 win loss record while averaging 28.8 points and 16.8 rebounds per game.[4]The team fulfilled their promise of winning the state title in Chastaine's honor by winning the state title game in overtime.[11]

Michigan State University

Although Johnson was recruited by top-ranked colleges such as Indiana and UCLA, he decided to play close to home.[12] Although he initially wanted to go to the University of Michigan, he eventually decided on Division I Michigan State University in East Lansing, after their basketball coach Jud Heathcote promised Johnson that he would play point guard.[13]

Initially, Johnson did not want to play professionally, and instead focused on his major of communication studies, and his desire to become a television commentator.[14] But playing with future NBA players Greg Kelser and Jay Vincent, Johnson averaged 17.0 points, 7.9 rebounds and 7.4 assists per game as a freshman, and led the Spartans to a 25–5 record, the Big Ten Conference title, and a berth in the 1978 NCAA tournament.[15] The Spartans reached the Elite Eight, but they lost narrowly to eventual national champion Kentucky.[16]

Before the 1978–79 season, Johnson was featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated, as one of the top ten sophomore players in the country.[17] During the season, Michigan State again qualified for the NCAA Tournament, where they advanced to the championship game, and faced Indiana State University, which was led by senior Larry Bird. In what is still the highest-rated college basketball game ever,[18] Michigan State defeated Indiana State 75–64, and Johnson was voted Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four.[11] At the end of the season, Johnson decided to declare himself eligible for the 1979 NBA Draft, and finished his career at Michigan State with averages of 17.1 points, 7.6 rebounds, and 7.9 assists per game.[19]

Rookie season in the NBA (1979–80)

Although the Los Angeles Lakers finished with 47 wins and advanced to the second round of the playoffs in the 1978–79 season,[20] they owned the first pick of the 1979 NBA Draft due to a previous trade with the New Orleans Jazz. Although the management of the Lakers were intitially skeptical of drafting Johnson, owner Jerry Buss eventually persuaded them to draft Johnson.[2] Johnson signed with Los Angeles for $500,000 a year, which was the highest rookie contract ever up to that point.[21] Johnson said that the "most amazing" part about being with the Lakers was to play alongside Kareem Abdul-Jabbar,[22] a 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) center who would become the leading scorer in NBA history.[23] But despite Abdul-Jabbar's dominance, he had failed to win a championship with the Lakers, and Johnson was expected to help the Lakers achieve their goal of a championship.[24] Johnson's averages of 18.0 points, 7.7 rebounds and 7.3 assists per game for the season ensured that he was named both an All-Rookie selection and an NBA All-Star Game starter, although the NBA Rookie of the Year Award went to his rival Bird, who had been drafted by the Boston Celtics.[19]

The Lakers compiled a 60–22 record in the regular season and reached the 1980 NBA Finals,[25] where they faced the Philadelphia 76ers, who were led by future Hall of Fame forward Julius Erving. The Lakers took a 3–2 lead, but Abdul-Jabbar, who averaged 33 points a game in the series,[26] sprained his ankle in Game 5, and was unable to play in the remainder of the series.[24] Paul Westhead, who had replaced Jack McKinney as head coach earlier in the season, decided to put Johnson at center, and in Game 6, Johnson recorded 42 points, 15 rebounds, seven assists and three steals, lifting the Lakers to a 123–107 win.[24] Johnson became the first and only rookie to win the NBA Finals MVP award,[24] and his clutch performance is still regarded as one of the finest ever in the NBA.[3][27][28] He also became one of only four players to win NCAA and NBA championships in consecutive years.[29]

Ups and downs (1980–83)

Early in the 1980–81 season, Johnson was sidelined after he suffered torn cartilage in his left knee. Johnson missed a total of 45 games,[19] and he said that the time of his rehabilitation was the "most down" he had ever been.[30] Johnson made his much-anticipated return before the start of the playoffs,[31] but the Lakers' assistant and future head coach Pat Riley later said that Johnson's return made the Lakers a "divided team".[32] The Lakers faced the Houston Rockets, who finished only 40–42 in the regular season,[33] in the first round, but the Rockets upset the Lakers 2–1, after Johnson airballed a last-second shot in Game 3 on a play originally designed for Abdul-Jabbar.[34] During the off-season, Johnson signed a 25-year, $25-million contract, which was the highest-paying contract in sports history up to that point.[35]

During the 1981–82 NBA season, Johnson had a serious dispute with Westhead, who Johnson said made the Lakers "predictable".[36] After Johnson demanded to be traded, Buss fired Westhead, and replaced him with Riley. Although Johnson denied responsibility for for Westhead's firing,[37] he was booed across the league, even by the Lakers' fans.[4] Despite his off-court troubles, Johnson averaged 18.6 points, 9.6 rebounds, 9.5 assists, and a league-high 2.7 steals per game, and was voted a member of the All-NBA Second Team.[19] He also joined Wilt Chamberlain and Oscar Robertson as the only NBA players to tally at least 700 points, 700 rebounds and 700 assists in the same season.[11] The Lakers advanced through the playoffs and faced Philadelphia for the second time in three years in the 1982 NBA Finals. After a triple-double from Johnson in Game 6, the Lakers defeated the Sixers 4–2, as Johnson won his second NBA Finals MVP award.[38] Johnson said his third season was when the Lakers started to become a great team,[39] and credited Riley with making Lakers successful.[40]

During the 1982–83 NBA season, Johnson averaged 16.8 points, 8.6 rebounds and 10.5 assists per game and earned his first All-NBA First Team nomination.[19] The Lakers again reached the Finals, and faced the Sixers for a third time, who featured future Hall of Fame center Moses Malone as well as Erving.[41] With Johnson's teammates Norm Nixon, James Worthy and Bob McAdoo all hobbled by injuries, the Lakers were swept by the Sixers, and Malone was crowned the Finals MVP.[41]

Battles with the Celtics (1983–87)

In Johnson's fifth year, he had another strong season of 17.6 points, 7.3 rebounds and 13.1 assists per game.[19] The Lakers reached the Finals for the third year in a row, where Johnson's Lakers and Bird's Celtics met for the first time in the post-season.[42] After winning the first game, the Lakers led by two points in Game 2 with only 18 seconds to go, but Johnson lost the ball to Celtic Gerald Henderson, who hit the tying layup. On the ensuing possession, Johnson failed to get a shot off before the final buzzer sounded, and the Lakers lost 124–121 in overtime.[42] In Game 3, Johnson responded with 21 assists in a 137–104 win, but in Game 4, Johnson again made several crucial errors late in the game. In the final minute of that game, Johnson had the ball stolenfrom him by Celtics center Robert Parish, and then missed two free throws which could have won the game. The Celtics won Game 4 in overtime, and the teams split the next two games. In the decisive Game 7 in Boston, trailing by three points in the final minute, opposing point guard Dennis Johnson stole the ball from Johnson, which effectively ended the series.[42] Johnson later termed it as "the one championship we should have had but didn't get".[43]

In the 1984–85 NBA season, Johnson returned to form and averaged 18.3 points, 6.2 rebounds and 12.6 assists per game in the regular season.[19] He led the Lakers into the 1985 NBA Finals, where they again played against the Celtics. The series started poorly for the Lakers, when they allowed an NBA Finals record 148 points to the Celtics in a 38 point loss in Game 1.[44] However, Abdul-Jabbar, who was now 38 years old, scored 30 points and grabbed 17 rebounds in Game 2, and his 36 points in the Game 5 win were instrumental in establishing a 3–2 lead for Los Angeles.[44] After the Lakers defeated the Celtics in six games, both Abdul-Jabbar and Johnson, who averaged 15.2 assists per game in the finals,[45] said the Finals win was the highlight of their careers.[46]

Johnson again averaged a double-double in the 1985–86 NBA season, with 18.8 points, 5.9 rebounds, and 12.6 assists per game.[19] But after advancing to the Western Conference Finals, the Lakers were unable to defeat Houston, who advanced to the Finals in five games.[47] However, in the next season, Johnson averaged a career-high of 23.9 points, as well as 6.3 rebounds and 12.2 assists per game,[19] and earned his first regular season MVP award.[2] The Lakers met the Celtics again in the 1987 NBA Finals, and in Game 4, Johnson hit a last-second hook shot over the outstretched arms of Celtics big men Robert Parish and Kevin McHale to win the game 107–106.[48] The game-winning shot, which Johnson dubbed his "junior, junior, junior sky-hook", put the Lakers up three games to one, and Los Angeles went on to win in six games. For his feats, Johnson was awarded his third Finals MVP title.[48]

Repeat and falling short (1987–91)

Before the 1987–88 NBA season, Lakers coach Pat Riley publicly promised the media that they would defend the NBA title, although the last team to successfully repeat their title was the Boston Celtics, who won the 1968 and 1969 Finals.[49] Johnson had another productive season with averages of 19.6 points, 6.2 rebounds, 11.9 assists per games.[19] In the 1988 playoffs, the Lakers survived two narrow 4–3 series against the Utah Jazz and the Dallas Mavericks to reach the Finals and face the Detroit Pistons,[50] who were nicknamed the "Bad Boys" because of their physical rough style of play.[51] After splitting the first six games 3–3, Laker forward and Finals MVP James Worthy had a triple-double of 36 points, 16 rebounds and 10 assists, powering his team to a 108–105 win.[52]

In the 1988–89 NBA season, Johnson's 22.5 points, 7.9 rebounds and 12.8 assists per game earned him his second MVP award,[19] and the Lakers reached the 1989 NBA Finals, where they again faced the Pistons. But after Johnson went down with a hamstring injury in Game 2, the Lakers were no match for the Pistons, who swept them 4–0.[53]

Although Abdul-Jabbar retired the following year, Johnson won his third MVP award after a strong regular season with averages of 22.3 points, 6.6 rebounds and 11.5 assists per game.[19] But the Lakers bowed out in the second playoff round to the Phoenix Suns, which was the Lakers earliest elimination in the playoffs in nine years.[54] Johnson performed well during the 1990–91 NBA season, with averages of 19.4 points, 7.0 rebounds, and 12.5 assists per game, and the Lakers reached the 1991 NBA Finals against the Chicago Bulls, who were led by shooting guard Michael Jordan, a five-time scoring champion regarded as the finest player of his era. Although the series was portrayed as a matchup between Johnson and Jordan,[55] Bulls defensive stalwart Scottie Pippen defended well against Johnson, and despite two triple-doubles from Johnson during the series, Finals MVP Jordan led his team to a 4–1 win.[4]

HIV announcement and Olympics (1991–92)

During a physical before the 1991–92 NBA season, it was discovered that Johnson had tested positive for HIV. In a press conference held on November 7, 1991, Johnson made a public announcement that he would retire immediately.[56] He stated that both his wife Cookie and their unborn child did not have HIV, and that he was going to dedicate his life to "battle this deadly disease".[56] Johnson initially said that he did not know how he contracted the disease,[56] but later admitted that it was through having multiple sexual partners during his playing career.[57] At the time, AIDS was commonly associated with homosexuality,[58] and only a small percentage of HIV-positive people had contracted it from heterosexual sex.[59] Rumors abounded that Johnson was gay or bisexual, but he denied that he was either.[59] The announcement, which was broadcast live across America,[59] became a major news story around the country,[60] and was later named as ESPN's 7th most memorable moment.[61] Many articles praised Johnson as a hero, and U.S. President George H. W. Bush said: "For me, Magic is a hero, a hero for anyone who loves sports."[62]

Despite his retirement, Johnson was still voted by fans into the 1992 NBA All-Star Game, although his former teammates Byron Scott and A.C. Green said that Johnson should not play,[63] and several NBA players, including Utah Jazz forward Karl Malone argued that they would be at risk of contamination if Johnson suffered an open wound while on court.[64] However, Johnson led the West to a 153–113 win and was crowned All-Star MVP after recording 25 points, 9 assists, and 5 rebounds.[65] The game ended after he made a last-minute three-pointer, and players from both teams ran onto the court, hugging him and exchanging high-fives.[66]

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's basketball | ||

| Representing | ||

| 1992 Barcelona | National team | |

Despite being HIV-positive, Johnson was chosen to compete in the 1992 Summer Olympics for the US basketball team, which was dubbed the "Dream Team" because of the numerous NBA stars on the roster.[67] During the tournament, Johnson played infrequently due to knee problems, but he received standing ovations from the crowd, and he used the opportunity to attempt to inspire HIV positive people.[14]

Post-Olympics and later life

Johnson announced that he would attempt a comeback to the Lakers for the 1992–93 NBA season. However, after he practiced and played in several pre-season games, he decided to return to retirement before the start of the regular season, citing controversy over his return from several NBA players.[11] After his retirement, Johnson engaged himself in several activities, including writing a book on safer sex, running several businesses, working for NBC as a commentator, building movie theaters in minority areas of Los Angeles, and touring Asia and Australia with a basketball team comprising former college and NBA players.[2]

In the 1993–94 NBA season, Johnson returned to the NBA as head coach of the Lakers, replacing Randy Pfund. But after he lost the next six, he announced he would not continue coaching, and instead purchased a 5% share of the Lakers in June of 1994, becoming a part-time owner.[4] In the following year, at the age of 36, Johnson again attempted a comeback as a player. Playing power forward, he averaged 14.6 points, 6.9 assists, and 5.7 rebounds per game in the last 32 games of the season.[19] But the Lakers lost to the Houston Rockets in the first round of the playoffs,[68] and Johnson retired permanently, saying: "I am going out on my terms, something I couldn't say when I aborted a comeback in 1992."[11]

Off the Court

In 1998, Johnson hosted a late night talk show on Fox called The Magic Hour, but the show was cancelled after two months due to low ratings.[69] Today, he runs Magic Johnson Enterprises, a company that has a net worth of 700 million dollars,[70] and owns several subsidiaries, including Magic Johnson Productions, a promotional company; Magic Johnson Theaters, a nationwide chain of movie theaters; and Magic Johnson Entertainment, a movie studio.[71] He also is an NBA analyst for Turner Network Television,[72] and he is a major supporter of the Democratic Party, and has endorsed Phil Angelides for Governor of California,[73] and Hillary Clinton for President of the United States.[74]

Johnson first fathered a son in 1981, when Andre Johnson was born to Melissa Mitchell.[70] In 1991, Johnson married Earlitha "Cookie" Kelly, with whom he had one son, Earvin III;[70] Johnson has also adopted a daughter, Elisa.[75] Johnson, who does not have AIDS, currently takes a drug cocktail from GlaxoSmithKline, which he endorses.[76]

HIV activism

After announcing his infection, Johnson teamed up with his physician Dr. Lynn Montana to help educate the world's youth about the risks associated with HIV.[14] Johnson also set up the Magic Johnson Foundation to help combat HIV,[77] although he later diversified the foundation to include other charitable goals.[78] In 1992, he joined the National Commission on AIDS, but left after only eight months, saying that the commission was not doing enough to combat the disease.[77] He was also the main speaker for the United Nations (UN) World AIDS Day Conference in 1999,[78] and he has served as a United Nations Messengers of Peace.[79] He does not have AIDS

Johnson stated that abstinence is the safest way to avoid contracting HIV via sexual contact, and he used his status as a basketball player to help debunk several popular misconceptions about HIV.[14] Previously, HIV had been associated with drug addicts and homosexuals,[77] but Johnson's admission and subsequent campaigns publicized a risk of infection that included everyone. Johnson stated that his aim was to "help educate all people about what [HIV] is about" and teach others not to "discriminate against people who have HIV and AIDS."[78] However, in recent years, he has also been criticized by the AIDS community for his decreasing involvement in halting and publicizing the spread of the disease.[77][78]

Career Legacy

Few athletes are truly unique, changing the way their sport is played with their singular skills.

— Introductory line of Johnson's biography, NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition[2]

Johnson played the point guard position and is considered as one of the most successful and unique players in the history of the game. He was a five-time NBA champion and a 12-time All-Star, earned a place on ten All-NBA teams, and was thrice named MVP of the regular season and the Finals. In 905 NBA games, he scored 17,707 points, 6,559 rebounds and 10,141 assists, translating to career averages of 19.5 points, 7.2 rebounds and 11.2 assists per game.[19] Johnson shares the single game playoff record for assists with 24,[80] holds the Finals record for assists in a game with 21,[80] and has the most playoff assists with 2,346.[81] He holds the All-Star Game single game record for assists with 22, and the All-Star Game record for career assists with 127.[80] Johnson also remains the NBA's all-time leader in assists per game.[1]

Johnson introduced an fast-paced style of basketball that became known as "Showtime", described as a mix of "no-look passes off the fastbreak, pin-point alley-oops from halfcourt, spinning feeds and overhand bullets under the basket through triple teams."[4] Fellow Lakers guard Michael Cooper stated that: "There have been times when he [Johnson] has thrown passes and I wasn't sure where he was going. Then one of our guys catches the ball and scores, and I run back up the floor convinced that he must've thrown it through somebody."[4][11] Johnson was also a unique because he played point guard despite being 6–9, a size reserved normally for frontcourt players.[4] Johnson combined the size of a power forward, the one-on-one skills of a swingman and the ball handling talent of a guard, making him one of the most dangerous triple-double threats of all time; his 138 triple-double-games are second only to Oscar Robertson's 181.[82]

For his feats, Johnson was voted as one of the 50 Greatest Players of All Time by the NBA in 1996,[83] and he was introduced into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2002.[84] In 2006, ESPN.com rated Johnson the greatest point guard of all time, and stated: "It could be argued that he's the one player in NBA history who was better than Michael Jordan."[3] Several of his achievements in individual games have also been named one of the top moments in the NBA.[28][85][86]

Rivalry with Larry Bird

Ever since the 1979 NCAA Finals, in which Johnson's Michigan State squad defeated Larry Bird's Indiana State team, Johnson and Bird were linked as rivals. From 1980 to 1988, their respective Lakers and Celtics teams won eight of nine NBA titles. The rivalry reached its climax in the mid-'80s, when their teams met in three NBA Finals (1984, 1985, 1987). Johnson appreciated the rivalry greatly, asserting that for him, the 82 game regular season was composed of 80 normal games and "the two", i.e. the Lakers-Celtics games. Similarly, Bird admitted that Johnson's box score was the first thing he looked at after every game day, stating everything else was unimportant.[66]

Several journalists hypothesised that the Johnson-Bird rivalry was so appealing because it represented many other rivalries, such as the clash between Lakers and Celtics, between Hollywood flash ("Showtime") and Boston/Indiana blue collar grit ("Celtics Pride"), and between blacks and whites.[87] [88] Apart from the on-court differences, the rivalry proved significant because it drew national attention to the faltering NBA. Prior to Johnson and Bird, the league had gone through a decade of declining interest and low TV ratings.[89] With the two Hall-of-Famers, the league won a whole generation of new fans,[90] drawing both traditionalist adherents of Bird's dirt court Indiana game and those appreciative of Johnson's public park flair. Sports journalist Larry Schwartz of ESPN even went as far as to assert that Johnson and Bird saved the NBA from bankruptcy.[11]

Despite their on-court rivalry Johnson and Bird became good friends privately, ironically during the filming of a joint 1984 Converse shoe ad which was meant to depict them as enemies.[91] When Bird retired in 1992, Johnson appeared at his retirement ceremony and described Bird as a "friend forever",[66] and During Johnson's induction into the Hall of Fame, Bird formally inducted Johnson in the ceremony.[90]

Books

Biographies

Johnson's autobiography is Johnson, Earvin (1992). Magic Johnson: My Life. Random House. ISBN 0449222543. Other biographies include:

- Haskins, James (1981). Magic: A Biography of Earvin Johnson. ISBN 0-89490-044-7.

- Morgan, Bill (1991). The Magic: Earvin Johnson. ISBN 0-606-01895-6.

- Gutman, Bill (1991). Magic: More Than a Legend. ISBN 0-06-100542-8.

- Gutman, Bill (1992). Magic Johnson: Hero On and Off the Court. ISBN 1-56294-287-5.

- Johnson, Rick L. (1992). Magic Johnson: Basketball's Smiling Superstar. ISBN 0-87518-553-3.

- Schwabacher, Martin (1993). Magic Johnson (Junior World Biographies). ISBN 0-7910-2038-X.

- Rozakis, Laurie (1993). Magic Johnson: Basketball Immortal. ISBN 0-86592-025-7.

- Frank, Steven (1994). Magic Johnson (Basketball Legends). ISBN 0-7910-2430-X.

- Blatt, Howard (1996). Magic! Against The Odds. ISBN 0-671-00301-1.

- Gottfried, Ted (2001). Earvin Magic Johnson: Champion and Crusader. ISBN 0-531-11675-1.

Instructional

- Johnson, Earvin "Magic" (1992). Magic's Touch: From Fundamentals to Fast Break With One of Basketball's All-Time Greats. ISBN 0-201-63222-5.

- Johnson, Earvin "Magic" (1996). What You Can Do to Avoid AIDS. ISBN 0-8129-2844-X.

- Updated version of Johnson, Earvin "Magic" (1992). Unsafe Sex in the Age of AIDS. ISBN 0-8129-2063-5.

References

- General

- Bork, Günter (1994). Die großen Basketball Stars. Copress-Verl. ISBN 3-7679-0369-5.

- Bork, Günter (1995). Basketball Sternstunden. Copress-Verl. ISBN 3-7679-0456-X.

- Specific

- ^ a b "All Time Leaders: Assists Per Game". NBA.com. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ a b c d e "Magic Johnson Summary". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ a b c "Daily Dime: Special Edition – The 10 Greatest Point Guards Ever". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Magic Johnson Bio". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Haire, Thomas (May 1, 2003). "Do You Believe in 'Magic'?". Response Magazine. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Magic Johnson - Basketball and Business Legend". nationwidespeakers.com. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 28.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zillgitt, Jeff (2002-09-27). "Magic Memories of a Real Star". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 37.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Schwartz, Larry. "Magic made Showtime a show". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 45.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 48.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Bork (1994), pp. 56–66.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. pp. 69–71.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "1978 NCAA Tournament". sportsline.com. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 73.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Katz, Andy. "From coast to coast, a magical pair". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Magic Johnson Statistics". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "1978–79 NBA Season Summary". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 91.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 113.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 113.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Rookie Makes the Lakers Believe in Magic". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ "1979–80 NBA Season Summary". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 107.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "NBA's Greatest Moments: Magic Fills in at Center". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ a b McCallum, Jack (2006-06-02). "Playoff moments can make legends". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "Magic Johnson timeline". USA Today. 2001-07-11. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 135.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 136.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Riley, Pat (1993). The Winner Within. G.P. Putnam's Son. p. 48.

- ^ "Houston Rockets". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 137.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 139.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 141.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 143.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lakers' Arduous Season Ends in Victory". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 148.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 149.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Moses Helps Dr. J, Sixers Reach Promised Land". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ a b c "Celtics Win First Bird-Magic Finals Showdown". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 196.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Aging Abdul-Jabbar Finds Youth". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Kareem, Lakers Conquer the Celtic Mystique". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 199.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "1986 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ a b "Magic Maneuvers Lakers Past Celtics". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ "Riley Guarantees A Repeat". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ "1988 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ "Bill Laimbeer career summary". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "Lakers Capture the Elusive Repeat". NBA.com. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ "Waiting Game Ends for Impatient Pistons". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ "1990 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ "Bulls Finally Get That Championship Feeling". nba.com. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ a b c Weinberg, Rick. "7: Magic Johnson announces he's HIV-positive". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Friend, Tom (2001-11-07). "Still stunning the world 10 years later". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Jim, McKay (2000). Masculinities, Gender Relations, and Sport: Masculinities, Gender Relations. SAGE. p. 53. ISBN 076191272X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Johnson. My Life. p. 225.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "gaydenial" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Masculinities, Gender Relations, and Sport: Masculinities, Gender Relations. p. 53.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Weinberg, Rick. "Magic Johnson announces he's HIV-positive". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Masculinities, Gender Relations, and Sport: Masculinities, Gender Relations. p. 54.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McCallum, Jack (1992-02-17). "Most Valuable Person". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Bork (1994), pp. 90–94.

- ^ Cooper, Jon. "1992 NBA All-Star Game". NBA.com. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ a b c "Classic NBA Quotes: Magic and Larry". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Ten of the 12 players on the team were named one of the NBA's 50 Greatest Players: "The Original Dream Team". NBA.com. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "1996 Playoff Results". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ "'Magic Hour' Canceled". New York Times. 1998-08-08. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ a b c Rovell, Darren (2005-10-08). "Passing on the Magic". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Walk, Gary Eng (October 7, 1998). "Magic Johnson joins the music biz". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "NBA 05-06 TNT". TNT.tv. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ "Magic Johnson backs Angelides for Governor". angelides.com. 2005-11-29. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "Magic Johnson, Bill Clinton team up for Hillary". USA Today. December 20, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Brozan, Nadine (1995-01-26). "Chronicle". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ "Magic Johnson assists drugmaker to advertise HIV treatment". USAToday.com. January 20, 2003. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d McCallum, Jack (August 20, 2001). "Life After Death". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Farrey, Tom (November 7, 1991). "AIDS community misses old Magic act". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rhoden, William C. (September 16, 1998). "Sports of The Times; The Greatest Is Honored by The Diplomat". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "Magic Johnson Career Stats". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ "All-Time Playoffs Individual Career Leaders". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Wojnarowski, Adrian (2006-11-18). "Making triple trouble". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "The NBA at 50". NBA.com. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ "Johnson, Brown elected to Hall of Fame". ESPN.com. June 5, 2002. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Forrester, Paul (2007-02-16). "Top 15 All-Star Weekend moments". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "The 60 Greatest Playoff Moments". NBA Encyclopedia: Playoff Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Bork (1995), pp. 49–55.

- ^ Halberstam, David (1987-06-29). "The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "'Magic' Time". CBS News. 2002-09-27. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ a b "Larry Bird inducting Magic Johnson". CBC Sports. 2002-08-15. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Johnson. My Life. p. 203.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Template:NBA-profile

- Template:Basketball-reference

- Magic Johnson Bio, NBA Encyclopedia, Playoff Edition

- Basketball Hall of Fame biography