Sri Lankan Tamils

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 1,871,535 (1981)[1] | |

| ~200,000 (2007)[2] | |

| ~100,000 (2005)[3] | |

| ~120,000 (2007)[4] | |

| ~60,000 (2008)[5] | |

| ~35,000 (2007)[6] | |

| ~24,436 (1970)[7] | |

| ~10,000 (2000)[8] | |

| ~9,000 (2003)[9] | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Hinduism of Saivite sect; minorities are Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indian Tamils, Portuguese Burghers, Sinhalese, Veddas | |

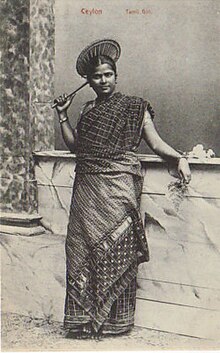

Sri Lankan Tamil people (Tamil: ஈழத் தமிழர், īḻat tamiḻar), or Ceylon Tamils, are the Tamil-speaking people of the South Asian island state of Sri Lanka. There is evidence of the presence of Sri Lankan Tamils on the island since the 2nd century BCE. Most modern Sri Lankan Tamils descend from the former Jaffna Kingdom in the north and Vannimais chieftaincies from the east. They constitute a majority in the Northern Province, live in significant numbers in the Eastern Province, and are in the minority throughout the rest of the country.

Sri Lankan Tamils are culturally and linguistically distinct from the other two Tamil speaking minorities in Sri Lanka, the Indian Tamils and the Muslims. Genetic studies indicate that they are closely related to the majority Sinhalese people. The Sri Lankan Tamils are mostly Hindus with a sizable Christian population. Sri Lankan Tamil literature on topics including religion and the sciences flourished during the medieval period in the court of the Jaffna Kingdom. Since the 1980's, it is distinguished by an emphasis on themes relating to the civil war. Sri Lankan Tamil dialects are noted for their archaism and retention of words not in every day use in the neighboring Tamil Nadu state in India.

Since Sri Lanka gained independence from Britain in 1948, relations between the majority Sinhalese and minority Tamil communities have been strained. Rising ethnic and political tensions, along with ethnic riots and pogroms in 1958, 1977, 1981 and 1983, led to the formation and strengthening of militant groups advocating independence for Tamils. The ensuing civil war has resulted in the deaths of more than 70,000 people and the forced disappearance of thousands of others.

Sri Lankan Tamils have historically migrated to find work, notably during the British colonial period. Since 1983, the beginning of the civil war, more than 800,000 Tamils have been displaced within Sri Lanka, and many have left the country for destinations such as India, Canada, and Europe.

History

Pre-Historic period

There is little scholarly consensus over the presence of the Tamil people in Sri Lanka, also known as Eelam in early Tamil literature, prior to the medieval Chola period (circa 10th century CE). One theory states that there was not an organized Tamil presence in Sri Lanka until the invasions from what is now South India in the 10th century CE, yet another theory contends that Tamil people were the original inhabitants of the island.[10][11] The indigenous Veddhas are physically related to Dravidian language-speaking tribal people in South India and early populations of Southeast Asia, although they no longer speak their native languages.[12] It is believed that cultural diffusion, rather than migration of people, spread the Sinhalese and Tamil languages from peninsular India into an existing Mesolithic population, centuries before the Christian era.[13]

Settlements of people culturally similar to those of present-day Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu in modern India were excavated at megalithic burial sites at Pomparippu on the west coast and in Kathiraveli on the east coast of the island, which were established between the 5th century BCE and 2nd century CE.[14][15] Cultural similarities in burial practices in South India and Sri Lanka were dated by archeologists to 10th century BCE. However, Indian history and archaeology has pushed the date back to 15th century BCE, and in Sri Lanka, there is radiometric evidence from Anuradhapura that the non-Brahmi symbol-bearing black and red ware occur at least around 9th or 10th century BCE.[16] There are other problems with dating include Dakhinathupa in Anuradhapura, currently identified as a Buddhist temple, was considered, until the 1900s CE, as the tomb of 2nd century BCE Tamil king Elara by the locals. The identification and reclassification is considered controversial.[17][18]

Historic period

Historical records establish that Tamil kingdoms in modern India were closely involved in the island's affairs from about the 2nd century BCE.[19][20] There is epigraphic evidence of traders and others identifying themselves as Damelas or Damedas (the Prakrit word for Tamil people) in Anuradhapura, the capital city of Rajarata, and other areas of Sri Lanka as early as the 2nd century BCE.[21] In Mahavamsa, a historical poem, ethnic Tamil adventurers such as Elara invaded the island around 145 BCE.[22] Soldiers from what is now South India were brought to Anuradhapura between the 7th and 11th centuries CE in such large numbers that local chiefs and kings trying to establish legitimacy came to rely on them.[23] There were Tamil villages collectively known as Demel-kaballa (Tamil allotment), Demelat-valademin (Tamil villages), and Demel-gam-bim (Tamil villages and lands) by the 8th century CE.[24]

Medieval period

In the 9th and 10th centuries CE, Pandya and Chola incursions into Sri Lanka culminated in the Chola annexation of the island, which lasted until the latter half of the 11th century CE.[25][26][27][23] The decline of Chola power in Sri Lanka was followed by the restoration of the Polonnaruwa monarchy in the late 11th century CE.[28] In 1215, following Pandya invasions, the Tamil-dominant Arya Chakaravarthi dynasty established an independent Jaffna kingdom[29] on the Jaffna peninsula and parts of northern Sri Lanka. The Arya Chakaravarthi expansion into the south was halted by Alagakkonara,[30] a man descended from a family of merchants from Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu. He was the chief minister of the Sinhalese king Parakramabahu V (1344–59 CE). Vira Alakeshwara, a descendant of Alagakkonara, later became king of the Sinhalese,[31] but he was overthrown by the Ming admiral Cheng Ho in 1409 CE. The Arya Chakaravarthi dynasty ruled over large parts of northeast Sri Lanka until the Portuguese conquest of the Jaffna Kingdom in 1619 CE. The coastal areas of the island were taken over by the Dutch and then became part of the British Empire in 1796 CE.

The caste structure of the majority Sinhalese has also accommodated Hindu immigrants from South India since the 13th century CE. This led to the emergence of three new Sinhalese caste groups: the Salagama, the Durava and the Karava.[32][33][34] The Hindu migration and assimilation continued until the eighteenth century.[32]

Society

Tamil-speaking communities

There are two groups of Tamils in Sri Lanka: the Sri Lankan Tamils and the Indian Tamils. The Sri Lankan Tamils (or Ceylon Tamils) are descendants of the Tamils of the old Jaffna Kingdom and east-coast chieftaincies called Vannimais. The Indian Tamils (or Hill Country Tamils) are descendants of bonded laborers sent from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka in the 19th century to work on tea plantations.[35] Furthermore, there is a significant Tamil speaking Muslim population in Sri Lanka; however, unlike Tamil Muslims from India, they do not identify as ethnic Tamils and are therefore listed as a separate ethnic group in official statistics.[36][37]

Most Sri Lankan Tamils live in the Northern and Eastern provinces and in the capital Colombo, whereas most Indian Tamils live in the central highlands.[37] Historically both groups have seen themselves as separate communities, although there is a greater sense of unity since 1980's.[38] In 1949, the United National Party government, which included G. G. Ponnambalam, leader of the Tamil Congress, stripped the Indian Tamils of their citizenship. This was opposed by S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, the leader of Tamil nationalist Federal Party, and most Tamil people.[39]

Under the terms of an agreement reached between the Sri Lankan and Indian governments in the 1960s, about 40 percent of the Indian Tamils were granted Sri Lankan citizenship, and many of the remainder were repatriated to India.[40]By the 1990s, most Indian Tamils had received Sri Lankan citizenship.[41]

Regional groups

Sri Lankan Tamils are categorized into three subgroups based on regional distribution, dialects, and culture: Negombo Tamils from the western part of the island, Eastern Tamils from the eastern part, and Jaffna or Northern Tamils from the north.

Negombo Tamils

Negombo Tamils, or Puttalam Tamils, are native Sri Lankan Tamils who live in the western Gampaha and Puttalam districts. The term does not apply to Tamil immigrants into these areas who have come from other parts of the island.[42] They are distinguished from other Tamils by their dialects, one of which is known as the Negombo Tamil dialect, and by aspects of their culture such as customary laws.[42][43][44]Most Negombo Tamils have assimilated into the Sinhalese ethnic group through a process known as Sinhalisation. Sinhalisation has been facilitated by caste myths and legends (see Passing (sociology)).[45]

In the Gampaha district, Tamils have historically inhabited the coastal region. In the Puttalam district, there was a substantial ethnic Tamil population until the first two decades of the 20th century.[45][46][47] Most of those who identify as ethnic Tamils live in the coastal village Udappu.[48] There are also some Tamil Christians, chiefly Roman Catholics, who have preserved their heritage in the major cities such as Negombo, Chilaw, Puttalam, and also in villages such as Mampuri.[45] Some residents of these two districts, especially the traditional fishermen, are bilingual, ensuring that the Tamil language survives as a lingua franca among migrating fishing communities across the island. Negombo Tamil dialect is spoken by about 50,000 people. This number does not include others, outside of Negombo city, who speak local varieties of the Tamil language.[44]

Some Tamil place names have been retained in these districts. Outside the Tamil-dominated northeast, the Puttalam District has the highest percentage of place names of Tamil origin in Sri Lanka. Composite or hybrid place names are also present in these districts.[49]

Eastern Tamils

Eastern Tamils inhabit a region that spans into Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and Ampara districts.[51] Their history and traditions are inspired by local legends, native literature, and colonial documents.[52] In the 1500s the area came under the control of the Kandyan kingdom, and from that time on, Eastern Tamil social development diverged from that of the Northern Tamils.

With an agrarian-based society, the Eastern Tamils follow a caste system similar to the South Indian or Dravidian kinship system. Eastern Tamil caste hierarchy is dominated by the Mukkuvar caste. The main feature of their society is the kuti system.[53] Although the Tamil word kuti means a house or settlement, in eastern Sri Lanka it is related to matrimonial alliances. It refers to the exogamous matrilineal clans and is found amongst most caste groups;[54] no man carries with him the kuti of his birth, but instead joins his wife’s kuti on marriage. Kuti also collectively own places of worship such as Hindu temples.[54] Each caste contains a number of kutis, with varying names. Aside from castes with an internal kuti system, there are seventeen caste groups, called Ciraikutis, or imprisoned kutis, whose members were considered to be in captivity, confined to specific services such as washing, weaving, and toddy tapping. However, such restrictions no longer apply.

The Tamils of the Trincomalee district have different social customs from their southern neighbors due to the influence of the Jaffna kingdom to the north.[54] The indigenous Veddha people of the east coast also speak Tamil and have become assimilated into the Eastern Tamil caste structure.[55] Most Eastern Tamils follow customary laws called Mukkuva laws codified during the Dutch colonial period.[56]

Northern Tamils

Jaffna's history of being an independent kingdom lends legitimacy to the political claims of the Sri Lankan Tamils, and has provided a focus for their constitutional demands.[57] Northern Tamil society is generally categorized into two groups: those who are from the Jaffna peninsula in the north, and those who are residents of the Vanni District to the immediate south. The Jaffna society is separated by caste divisions, with social dominance attained by Vellalar, by means of myths and legends. Historically, the Vellalar, who form approximately fifty percent of the population, were involved in agriculture, using the services of castes collectively known as Panchamar (Tamil for group of five). The Panchamar consisted of the Nalavar, Pallar, Parayar, Vannar, and Ambattar.[57] Others such as the Karaiyar (fishermen) existed outside the agriculture-based caste system.[58] The caste of temple priests known as Iyers were also held in high esteem.[58]

People in the Vanni districts considered themselves separate from Tamils of the Jaffna peninsula but the two groups did intermarry. Most of these married couples moved into the Vanni districts where land was available. Vanni consists of a number of highland settlements within forested lands using irrigation tank-based cultivation. An 1890 census listed 711 such tanks in this area. Hunting and raising livestock such as water buffalo and cattle is a necessary adjunct to the agriculture. The Tamil-inhabited Vanni consists of the Vavuniya, Mullaitivu, and Eastern Mannar district. Historically, the Vanni area has been in contact with what is now South India, including during the medieval period (see Vanniar).[57] Northern Tamils follow customary laws called Thesavalamai, codified during the Dutch colonial period.[59]

Genetic affinities

Sri Lanka's important position on trade routes has brought people from many places, such as Africa, the Middle East, Europe, South East Asia, and neighboring India. The heterogeneous origins of the current Sri Lankan people can also be read in the mythical, legendary, and historical records of Sri Lanka.[60] A study by G.K. Kshatriya et al. compared the degree of gene diversity and genetic admixture among the Sri Lankan population groups with the populations of southern, northeastern, and northwestern India, the Middle East, and Europe. These analyses indicated that present-day Tamils and Sinhalese are genetically closest to Indian Tamils and South Indian Muslims. They are farther removed from Gujaratis and Punjabis of northwest India and farthest from the indigenous Veddahs.[60] The study of the genetic admixture also indicated that the Tamils of Sri Lanka have received a higher contribution from the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka than from the Tamils of India. The study did not find any correlation with population groups in India's northwest.[60] A further study by Papiha et al. confirmed the Sri Lankan Tamil population's close genetic affinity to the Sinhalese.[61]

Religion

In 1981, about eighty percent of Sri Lankan Tamils were Hindus who followed the Shaiva sect.[62] The rest were mostly Roman Catholics who converted after the Portuguese conquest of the Jaffna Kingdom and coastal Sri Lanka. There is also a small minority of Protestants due to missionary efforts in the 18th century by organizations such as the American Ceylon Mission.[63] Most Tamils who inhabit the Western Province are Roman Catholics, while those of the Northern and Eastern Provinces are mainly Hindu.[64] Pentecostal and other churches, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, are active among the internally displaced and refugee populations.[65]

The Hindu elite follow the religious ideology of Shaiva Siddhanta (Shaiva school) while masses practice folk Hinduism, upholding their faith in local village deities not found in formal Hindu scriptures. The place of worship depends on the object of worship and how it is housed. It could be a proper Hindu temple known as a Koyil, constructed according to the Agamic scripts (a set of scriptures regulating the temple cult). Very often, however, the temple is not completed in accordance with Agamic scriptures but consists of the barest essential structure housing a local deity.[64] These temples observe daily Puja (prayers) hours and are attended by locals. Both types of temples have a resident ritualist or priest known as a Kurukkal. A Kurukkal may belong to the Iyer community or be someone from a prominent local lineage.[64] Other places of worship do not have icons for their deities. The sanctum could house a trident (culam), a stone, or a large tree. Temples of this type are common in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, with a typical village having up to 150 such structures. The offering would be done by an elder of the family who owns the site. A coconut oil lamp would be lit on Fridays, and a special rice dish known as pongal would be cooked either on a day considered auspicious by the family or on the Thai Pongal day, and possibly on Tamil New Year Day.

The deities worshipped could be one of the following: Ayyanar, Annamar, Vairavar, Kali, Pillaiyar, Murukan, or Pattini. In the villages, it is the Pillaiyar temples, patronized by local farmers, that are the most numerous.[64] Tamil Roman Catholics, along with members of other faiths, worship at the Madhu church,[66] whereas Hindus have a number of temples with historic importance such as those at Ketheeswaram, Koneswaram, Naguleswaram, Munneswaram, and Nallur Kandaswamy.[67] Kataragama temple and Adams Peak are attended by all religious communities.

Language

Tamil dialects are differentiated by the phonological changes and sound shifts in their evolution from classical or old Tamil (3rd century BCE–7th century CE). The Sri Lankan Tamil dialects form a group that is distinct from the dialects of the modern Tamil Nadu and Kerala states of India. They are classified into three subgroups: the Jaffna Tamil, the Batticaloa Tamil, and the Negombo Tamil dialects. These dialects are also used by ethnic groups other than Tamils such as Muslims, Veddhas, and Sinhalese. Tamil loan words in Sinhala also follow the characteristics of Sri Lankan Tamil dialects.[68]

The Negombo Tamil dialect is used by bilingual fishermen in the Negombo area, who otherwise identify themselves as Sinhalese. This dialect has undergone considerable convergence with spoken Sinhala.[43] The Batticaloa Tamil dialect is shared between Tamils, Muslims, Veddhas and Portuguese Burghers in the Eastern Province. The Tamil dialect used by residents of the Trincomalee District has many similarities with the Jaffna Tamil dialect.[68] Batticaloa Tamil dialect is the most literary of all the spoken dialects of Tamil. It has preserved several ancient features, remaining more consistent with the literary norm, while at the same time developing a few innovations. It also has its own distinctive vocabulary and retains words that are unique to present-day Malayalam, a Dravidian language from Kerala that originated as a dialect of old Tamil around 9th century CE.[69][70]

The dialect used in Jaffna is the oldest and closest to old Tamil. It preserves many ancient features of old Tamil that predate Tolkappiyam,[68] the grammatical treatise on Tamil which is dated from 3rd century BCE to 10th century CE. [71] The long physical isolation of the Tamils of Jaffna has enabled their dialect to preserve antique features. Their ordinary speech closely approaches classical Tamil.[68] The Jaffna Tamil dialect and the Indian Tamil dialects are not mutually intelligible,[72] and the former is frequently mistaken for Malayalam by native Indian Tamil speakers.[73] There are also Prakrit loan words that are unique to Jaffna Tamil.[74][75]

Education

Sri Lankan Tamil society values education highly, for its own sake as well as for the opportunities it provides.[44] The kings of the Aryacakravarti dynasty were historically patrons of literature and education. Temple schools and traditional gurukulam classes on verandahs (known as Thinnai Pallikoodam in Tamil) spread basic education in religion and in languages such as Tamil and Sanskrit to the upper classes.[76] The conquest of the Jaffna kingdom by the Portuguese in 1619 introduced western-style education. The Jesuits opened churches and seminaries, but the Dutch destroyed them and opened their own schools attached to Dutch Reformed churches when they took over Tamil speaking regions of Sri Lanka.[77]

The primary impetus for educational opportunity came with the establishment of the American Ceylon Mission in Jaffna, which started with the arrival in 1813 of missionaries sponsored by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. The critical period of the missionaries' impact was from the 1820s to the early 1900s. During this time, they created Tamil translations of English texts, engaged in printing and publishing, established primary, secondary, and college-level schools, and provided health care for residents of the Jaffna Peninsula. American activities in Jaffna also had other unintended consequences. The concentration of efficient Protestant mission schools in Jaffna produced a revival movement among local Hindus led by Arumuga Navalar, who responded by building many more schools within the Jaffna peninsula. Local Catholics also started their own schools in reaction, and the state had its share of primary and secondary schools. Saturated with educational opportunities, many Tamils became literate. This prompted the British colonial government to hire Tamils as government servants in British-held Ceylon, India, Malaysia, and Singapore.[78]

By the time Sri Lanka became independent in 1948, approximately 60 percent of government jobs were held by Tamils, who formed barely fifteen percent of the population. The elected leaders of the country saw this as the result of a British stratagem to control the majority Sinhalese, and deemed it a situation that needed correction by implementation of the policy of standardization.[79][80]

Literature

According to legends, the origin of Sri Lankan Tamil literature dates back to the Sangam period (3rd century BCE–6th century CE). These legends indicate that the Tamil poet Eelattu Poothanthevanar (Poothanthevanar from Sri Lanka) lived during this period.[81]

Medieval period Tamil literature on the subjects of medicine, mathematics and history was produced in the courts of the Jaffna Kingdom. During Singai Pararasasekaran's rule, an academy for the propagation of the Tamil language, modeled on those of ancient Tamil Sangam, was established in Nallur. This academy collected manuscripts of ancient works and preserved them in the Saraswathy Mahal library.[76][82]

During the Portuguese and Dutch colonial periods (1619–1796), Muttukumara Kavirajar is the earliest known author who used literature to respond to Christian missionary activities. He was followed by Arumuga Navalar, who wrote and published a number of books.[81] The period of joint missionary activities by the Anglican, American Ceylon, and Methodist Missions also saw the expansion of translation activities.

The modern period of Tamil literature began in the 1960s with the establishment of modern universities and a free education system in post-independence Sri Lanka. The 1960s also saw a social revolt against the caste system in Jaffna, which impacted Tamil literature: Dominic Jeeva was a product of this period.[81]

After the start of the civil war in 1983, a number of poets and fiction writers became active, focusing on subjects such as death, destruction, and rape. Such writings have no parallels in any previous Tamil literature.[81] The war produced displaced Tamil writers around the globe who recorded their longing for their lost homes and the need for integration with mainstream communities in Europe and North America.[81]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Sri Lankan Tamils draws influence from that of India, as well as from colonialists and foreign traders. Rice is usually consumed daily and can be found at any special occasion, while spicy curries are favorite dishes for lunch and dinner. Rice and curry is the name for a range of Sri Lankan Tamil dishes distinct from Indian Tamil cuisine, with regional variations between the island's northern and eastern areas. While rice with curries is the most popular lunch menu, combinations such as curd, tangy mango, and tomato rice are also commonly served.[83]

String hoppers, which are made of rice flour and look like knitted vermicelli neatly laid out in circular pieces about Template:Cm to in in diameter, are frequently combined with tomato sothi (a soup) and curries for breakfast and dinner.[84] Another common item is puttu, a granular, dry, but soft steamed rice powder cooked in a bamboo cylinder with the base wrapped in cloth so that the bamboo flute can be set upright over a clay pot of boiling water. This can be transformed into varieties such as ragi, spinach, and tapioca puttu. There are also sweet and savory puttus.[85] Another popular breakfast or dinner dish is Appam, a thin crusty pancake made with rice flour, with a round soft crust in the middle.[86] It has variations such as egg or milk Appam.[83]

Jaffna, as a peninsula, has an abundance of seafood such as crab, shark, fish, prawn, and squid. Meat dishes such as mutton, chicken, pork, and beef also have their own niche. The vegetable curries, primarily from the home garden, use ingredients such as pumpkin, yam, jackfruit seed, hibiscus flower, and various green leaves. Coconut milk and hot chilly powder are also frequently used. Appetizers can consist of a range of achars (pickles) and vadahams. Snacks and sweets are generally of the homemade "rustic" variety, relying on jaggery, sesame seed, coconut, and gingelly oil, to give them their distinct regional flavor. A popular alcoholic drink in rural areas is palm wine, made from palm tree sap. Snacks, savories, sweets and porridge produced from the palmyra form a separate but unique category of foods; from the fan-shaped leaves to the root, the palmyra palm forms an intrinsic part of the life and cuisine of northern region.[83]

Politics

The continuous political rancor between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils is a hallmark of Sri Lanka's modern history. The Sri Lankan Civil War has had several underlying causes: the ways in which modern ethnic identities have been made and remade since the colonial period, the political struggle between minority Sri Lankan Tamils and the Sinhala-dominated government (accompanied by rhetorical wars over archaeological sites and place name etymologies), and the political use of the national past.[87] Sri Lanka has been unable to contain its ethnic violence as it escalated from sporadic terrorism to mob violence, and finally to civil war.[88] The civil war has resulted in the death of over 70,000 people[89] and, according to human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch, the forced disappearance of thousands of others (see White van abductions in Sri Lanka).[90][91][92] Since 1983, Sri Lanka has also witnessed massive civilian displacements of more than a million people, with eighty percent of them being Sri Lankan Tamils.[93]

Before independence

The arrival of Protestant missionaries on a large scale beginning in 1814 was a primary contributor to the development of political awareness among Sri Lankan Tamils. Activities by missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and Methodist and Anglican churches led to a revival among Hindu Tamils who created their own social groups, built their own schools and temples, and published their own literature to counter the missionary activities. The success of this effort led to a new confidence for the Tamils, encouraging them to think of themselves as a community, and it paved the way for their emergence as a cultural, religious, and linguistic society in the mid-19th century.[94][95]

Britain, having control of the whole island by 1815, established a legislative council in 1833 with three European seats and one seat each for Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamils, and Burghers. This council's primary function was to act as advisor to the Governor, and the seats eventually became elected positions.[96] There was initially little tension between the Sinhalese and the Tamils, when Ponnambalam Arunachalam, a Tamil, was appointed representative of the Sinhalese as well as of the Tamils in the national legislative council. British Governor William Manning, however, actively encouraged the concept of "communal representation".[97] Subsequently, the Donoughmore Commission rejected communal representation and brought in universal franchise. This decision was opposed by the Tamil political leadership, who realized that they would be reduced to a minority in parliament according to their proportion of the overall population. G. G. Ponnambalam, a leader of the Tamil community, suggested to the Soulbury Commission that a roughly equal number of seats be assigned to Tamils and Sinhalese in an independent Ceylon—a proposal that was rejected.[98] But under section 29(2) of the constitution formulated by the commissioner, additional protection was provided to minority groups, such requiring a two-thirds majority for any amendments and a scheme of representation that provided more weight to the ethnic minorities.[99]

After independence

Following independence in 1948, G. G. Ponnambalam and his Tamil Congress joined D. S. Senanayake's moderate, western-oriented United National Party. The Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948, which denied citizenship to Sri Lankans of Indian origin, split the Tamil Congress. S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, the leader of the splinter Federal Party (FP), contested the citizenship act before the Supreme Court, and then in the Privy council in England, but failed to overturn it. The FP eventually became the dominant Tamil political party.[100] In response to the Sinhala Only Act in 1956, which made Sinhala the sole official language, Federal Members of Parliament staged a nonviolent sit-in (satyagraha) protest, but it was violently broken up by a mob. The FP was blamed and briefly banned after the mini pogrom of May–June 1958 targeting Tamils, in which many were killed and thousands forced to flee their homes.[101] Another point of conflict between the communities was state sponsored colonization schemes that effectively changed the demographic balance in the Eastern Province, an area Tamil nationalists considered to be their traditional homeland, in favor of the majority Sinhalese.[102][88]

In 1972, a newly formulated constitution removed section 29(2) of the 1947 Soulbury constitution that was formulated to protect the interests of minorities.[103] Also, in 1973, the policy of standardization was implemented by the Sri Lankan government, supposedly to rectify disparities in university enrollment created under British colonial rule. The resultant benefits enjoyed by Sinhalese students also meant a significant decrease in the number of Tamil students within the Sri Lankan university student population.[104]

Shortly thereafter, in 1973, the Federal Party decided to demand a separate Tamil state. In 1975 they merged with the other Tamil political parties to become the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). [105] By 1977 most Tamils seemed to support the move for independence by electing the Tamil United Liberation Front overwhelmingly.[106] The elections were followed by the 1977 riots, in which around 300 Tamils were killed.[107] There was further violence in 1981 when an organized mob went on a rampage during the nights of May 31 to June 2, burning down the Jaffna public library, at the time one of the largest libraries in Asia, containing more than 97,000 books and manuscripts.[108][109]

Rise of militancy

Since 1948, successive governments have adopted policies that had the net effect of assisting the Sinhalese community in such areas as education and public employment.[110] These policies made it difficult for middle class Tamil youth to enter university or secure employment.[110][111] The individuals belonging to this younger generation, often referred to by other Tamils as "the boys" (Potiyal in Tamil), formed many militant organizations.[110] The most important contributor to the strength of the militant groups was the Black July pogrom, thought to have been an organized event, in which over 1,000 Sri Lankan Tamil civilians were killed, prompting many youths to choose the path of armed resistance.[110][112]

By the end of 1987, the militant youth groups had fought not only the Sri Lankan security forces and the Indian Peace Keeping Force, but they also fought among each other, with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) eventually eliminating most of the others. Except for the LTTE, many of the remaining organizations transformed into either minor political parties within the Tamil National Alliance or standalone political parties. Some also function as paramilitary groups within the Sri Lankan military.[110]

Human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as the United States Department of State[113] and the European Union,[114] have expressed concern about the state of human rights in Sri Lanka, and both the government of Sri Lanka and the rebel LTTE have been accused of human rights violations. Although Amnesty International found, in 2003, considerable improvement in the human rights situation, attributed to a ceasefire and peace talks between the government and the LTTE,[115] by 2007 they reported an escalation in political killings, child recruitment, abductions, and armed clashes which created a climate of fear in the north and east of the country.[116]

Migrations

Pre-independence

The earliest Tamil speakers from Sri Lanka known to have traveled from the island to foreign lands were members of a merchant guild calling itself Tenilankai Valanciyar (Valanciyar from Lanka of the South). They left behind inscriptions in South India dated to the 13th century.[117] In the late 19th century, educated Tamils from the Jaffna peninsula migrated to the British colonies of Malaya (Malaysia and Singapore) and India to assist the colonial bureaucracy. They worked in almost every branch of public administration, as well as on plantations and in industrial sectors. Prominent Malaysian Ananda Krishnan,[118] included in the Forbes list of billionaires, is of Sri Lankan Tamil descent. Singapore's former foreign minister and deputy prime minister, S. Rajaratnam, is also of Sri Lankan Tamil descent.[119] C. W. Thamotharampillai, an Indian-based Tamil language revivalist, was born in the Jaffna peninsula and settled in India.[120]

Post civil war

After the start of the conflict between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, there was a mass migration of Tamils trying to escape the hardships and perils of war. Initially, it was middle class professionals, such as doctors and engineers, who emigrated; they were followed by the poorer segments of the community. The fighting has driven more than 800,000 Tamils from their homes to other places within Sri Lanka as internally displaced persons and also overseas, prompting the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to identify them in 2004 as the largest asylum-seeking group.[3][121]

The country with the largest share of displaced Tamils is Canada, with more than 200,000 legal residents, found mostly within the Greater Toronto Area. The Tamil Canadians are a well-integrated group,[2] and there are a number of prominent Canadians of Sri Lankan Tamil descent, such as author Shyam Selvadurai,[122] and Indira Samarasekera,[123] president of the University of Alberta. Neighboring India has provided refuge to over 100,000 in special camps and another 50,000 outside of the camps.[3] In western European countries, the refugees and immigrants have integrated themselves into society where permitted. Tamil British singer M.I.A, also known as Mathangi Arulpragasam,[124] and BBC journalist George Alagiah[125] are, among others, notable people of Sri Lankan Tamil descent. Sri Lankan Tamil Hindus have built a number of prominent Hindu temples across North America and Europe, notably in Canada, France, Germany, Denmark, and the UK.[5][9]

See also

Notes

- ^ Karthigesu, S, Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics, p. 4

- ^ a b Foster, Carly (2007). "Tamils: Population in Canada". Ryerson University. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

According to government figures, there are about 200,000 Tamils in Canada

- ^ a b c Acharya, Arunkumar (2007). "Ethnic conflict and refugees in Sri Lanka" (PDF). Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ "Britain urged to protect Tamil Diaspora". BBC. 2006-03-26. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

According to HRW, there are about 120,000 Sri Lankan Tamils in the UK.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Baumann, Martin (2008). "Immigrant Hinduism in Germany: Tamils from Sri Lanka and Their Temples". Harvard university. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

Since the escalation of the Sinhalese-Tamil conflict in Sri Lanka during the 1980s, about 60,000 came as asylum seekers

- ^ "Swiss Tamils look to preserve their culture". Swissinfo. 2006-02-18. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

An estimated 35,000 Tamils now live in Switzerland,

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rajakrishnan, P. (1993). "Social Change and Group Identity among the Sri Lankan Tamils". Indian Communities in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Times Academic Press. pp. pp. 541–557. ISBN 9812100172.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Raman, B (2000-07-20). "Sri Lanka: The dilemma". The Hindu. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

It is estimated that there are about 10,000 Sri Lankan Tamils in Norway -- 6,000 of them Norwegian citizens, many of whom migrated to Norway in the 1960s and the 1970s to work on its fishing fleet; and 4,000 post-1983 political refugees.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Mortensen. Viggo, Theology and the Religions: A Dialogue, p. 110

- ^ Natarajan, V., History of Ceylon Tamils, p. 9

- ^ Manogaran, C. Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka, p. 2

- ^ "Vedda". Encyclopedia Britanica Online. London: Encyclopedia Britanica. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Indrapala. K, The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp. 53–54

- ^ de Silva, A History of Sri Lanka, p. 129

- ^ Indrapala, K., The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 91

- ^ Subramanian, T.S. (2006-01-27). "Reading the past in a more inclusive way:Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne". Frontline. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Harichandra, The sacred city of Anuradhapura, p. 19

- ^ Indrapala, K., The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 368

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 30–32

- ^ Mendis, G.C.Ceylon Today and Yesterday, pp. 24–25

- ^ Indrapala, K., The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 157

- ^ Nadarajan, V., History of Ceylon Tamils, p. 40

- ^ a b Spencer, George W. "The politics of plunder: The Cholas in eleventh century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3). Association for Asian Studies: 408.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Indrapala, K The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp. 214–215

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 46, 48, 75.

- ^ Mendis, G.C. Ceylon Today and Yesterday, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Smith, V.A. The Oxford History of India, p. 224

- ^ de Silva, C.R.Sri Lanka — A History, p. 76

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 100–102

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 102–104.

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, p. 104

- ^ a b de Silva, A History of Sri Lanka, p. 121

- ^ Spencer, Sri Lankan history and roots of conflict, p. 23

- ^ Indrapala, K., The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 275

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 177, 181

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, pp. 3–5, 9

- ^ a b Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka. "Population by Ethnicity according to District" (PDF). statistics.gov.lk. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^ V. Suryanarayan (2001). "In search of a new identity". Frontline. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hoole, Ranjan (2001). "Missed Opportunities and the Loss of Democracy: The Disfranchisement of Indian Tamils: 1948-49". UTHR. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, p. 262

- ^ de Silva, C.R. Sri Lanka — A History, p. 262

- ^ a b Fernando v. Proctor el al, 3 Sri Lanka 924 (District Court, Chilaw 1909-10-27).

- ^ a b Steven Bonta (June 2008). "Negombo Fishermen's Tamil (NFT): A Sinhala Influenced Dialect from a Bilingual Sri Lankan Community". International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. 37.

- ^ a b c Gair, James.,Studies in South Asian Linguistics, p. 171

- ^ a b c Foell, Jens (2007). "Participation, Patrons and the Village: The case of Puttalam District". University of Sussex. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

One of the most interesting processes in Mampuri is the one of Sinhalisation. Whilst most of the Sinhala fishermen used to speak Tamil and/or still do so, there is a trend towards the use of Sinhala, manifesting itself in most children being educated in Sinhala and the increased use of Sinhala in church. Even some of the long-established Tamils, despite having been one of the most powerful local groups in the past, due to their long local history as well as caste status, have adapted to this trend. The process reflects the political domination of Sinhala people in the Government controlled areas of the country.

- ^ Goonetilleke, Susantha (1980-05-01). "Sinhalisation: Migration or Cultural Colonization?". Lanka Guardian. pp. 22–29.

- ^ Goonetilleke, Susantha (1980-05-15). "Sinhalisation: Migration or Cultural Colonization?". Lanka Guardian. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Corea, Henry (1960-10-03). "The Maravar Suitor". The Sunday Observer. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kularatnam, K (April 1966). "Tamil Place Names in Ceylon outside the Northern and Eastern Provinces". Proceedings of the First International Conference Seminar of Tamil Studies, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia vol.1. International Association of Tamil Research. pp. 486–493.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Indrapala, K, Evolution of an ethnic identity.., p. 230

- ^ Kartithigesu, Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics, pp. 2–4

- ^ Subramaniam, Folk traditions and songs of Batticaloa district, pp. 1–13

- ^ Yalman, N., Under the bo tree: studies in caste, kinship, and marriage in the interior of Ceylon, pp. 282–335

- ^ a b c Kartithigesu, Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics, pp. 5–6

- ^ Seligmann, C.G. (1911). "The Veddas": 331–335.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tambiah, H.W., The laws and customs of the Tamils of Jaffna, p. 2

- ^ a b c Kartithigesu, S, Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics, pp. 4–12

- ^ a b Gunasingam, M Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 62

- ^ Tambiah, H.W., The laws and customs of the Tamils of Jaffna, p. 12

- ^ a b c Kshatriya, G.K. (1995). "Genetic affinities of Sri Lankan populations". Human Biology. 67 (6). American Association of Anthropological Genetics: 843–66. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ Papiha, S. S (1996). "Genetic Variations in Sri Lanka". Human Biology. 68 (5). American Association of Anthropological Genetics: 735. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sri Lanka:Country study". The Library of Congress. 1988. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Hudson, Religious Controversy in British India: Dialogues in South Asian Languages, p. 29

- ^ a b c d Karthigesu, Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics, pp. 34–89

- ^ "Overview: Pentecostalism in Asia". The pew forum. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "Tamil Tigers appeal over shrine". BBC. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ^ Manogaran, Chelvadurai, The untold story of the ancient Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 46

- ^ a b c d Kuiper, L.B.J (March 1964). "Note on Old Tamil and Jaffna Tamil". Indo-Iranian Journal. 6 (1). Springer Netherlands: 52–64. doi:10.1007/BF00157142.

- ^ Subramaniam, Folk traditions and songs of Batticaloa district, p. 10

- ^ Zvlebil, Kamil (June 1966). "Some features of Ceylon Tamil". Indo-Iranian Journal. 9 (2). Springer Netherlands: 113–138. doi:10.1007/BF00963656.

- ^ Swamy, B.G.L. (1975). "The Date Of Tolksppiyam-a Retrospect". Annals of Oriental Research. Silver Jubilee Volume: 292–317.

- ^ Schiffman, Harold (1996-10-30). "Language Shift in the Tamil Communities of Malaysia and Singapore: the Paradox of Egalitarian Language Policy". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Indrapala, K The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 45

- ^ Indrapala, K The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 389

- ^ Ragupathy, Tamil Social Formation in Sri Lanka: A Historical Outline, p. 1

- ^ a b Gunasingam, M Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, pp. 64–65

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 68

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, pp. 73–109

- ^ Pfaffenberger, B. The Sri Lankan Tamils, p. 110

- ^ Ambihaipahar, Scientific Tamil Pioneer, p. 29

- ^ a b c d e Sivathamby, Karthigesu (2005). "50 years of Sri Lankan Tamil literature". Tamil Circle. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ Nadarajan, V History of Ceylon Tamils, pp. 80–84

- ^ a b c Ramakrishnan, Rohini (2003-07-20). "From the land of the Yaal Padi". The Hindu. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pujangga, A requiem for Jaffna, p. 75

- ^ Pujangga, A requiem for Jaffna, p. 72

- ^ Pujangga, A requiem for Jaffna, p. 73

- ^ Spencer, J, Sri Lankan history and roots of conflict, p. 23.

- ^ a b Peebles, Patrick (February 1990). "Colonization and Ethnic Conflict in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka". Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (1). Association for Asian Studies: 30–55. doi:10.2307/2058432.

- ^ "Sri Lanka civilian toll 'appalling'". BBC. 2006-02-28. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Correspondents say that fighting between the two sides since then has killed more than 70,000 people. More than 1,000 people have been killed since the government withdrew from the ceasefire, according to the military.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Sri Lanka rapped over 'disappeared'". BBC. 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Sri Lanka's government is one of the world's worst perpetrators of enforced disappearances, US-based pressure group Human Rights Watch (HRW) says. An HRW report accuses security forces and pro-government militias of abducting and "disappearing" hundreds of people - mostly Tamils - since 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Fears grow over Tamil abductions". BBC. 2006-09-26. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

The image of the "white van" invokes memories of the "era of terror" in the late 1980s when death squads abducted and killed thousands of Sinhala youth in the south of the country. The Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) says the "white van culture" is now re-appearing in Colombo to threaten the Tamil community.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ ""Disappearances" on rise in Sri Lanka's dirty war". The Boston Globe. 2006-05-15. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

The National Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka has recorded 419 missing people in Jaffna since December 2005.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Newman, Jesse (2003). "Narrating displacement:Oral histories of Sri Lankan women". Refugee Studies Centre- Working papers (15). Oxford University: 3–60.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 108.

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 201.

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 76.

- ^ K. M. de Sila, History of Sri Lanka, Penguin 1995

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 5.

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 6.

- ^ Russel, Ross (1988). "Sri Lanka:Country study". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Roberts, Michael (November 2007). "Blunders in Tigerland: Papes muddles on suicide bombers". Heidelberg papers on South Asian and comparative politics. 32. University of Heidelberg: 14.

- ^ Russel, Ross (1988). "Tamil Alienation". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 6.

- ^ Jayasuriya, J. E. (1981). Education in the Third World. Pune: Indian Institute of Education. OCLC 7925123.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, pp. 101–110.

- ^ Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism, p. 7.

- ^ Kearney, R.N. (1985). "Ethnic Conflict and the Tamil Separatist Movement in Sri Lanka". Asian Survey. 25 (9): 898–917. doi:10.1525/as.1985.25.9.01p0303g. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Wilson, A.J. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, p. 125.

- ^ Knuth, Rebecca (2006). "Destroying a symbol" (PDF). IFLA. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ a b c d e Russel, Ross (1988). "Tamil Militant Groups". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Shastri, A. (1990). "The Material Basis for Separatism: The Tamil Eelam Movement in Sri Lanka". Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (1): 56–77. doi:10.2307/2058433. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ^ Marschall, Wolfgang (2003). "Social Change Among Sri Lankan Tamil Refugees in Switzerland". University of Bern. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ Sri Lanka "2000 Human Rights Report:Sri Lanka". United States Department of State. 2000. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "The EU's relations with Sri Lanka - Overview". European Union. 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ "Open letter to LTTE, SLMM and SL Police concerning recent politically motivated killings and abductions in Sri Lanka". Amnesty International. 2003. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Amnesty International report for Sri Lanka 2007". Amnesty International. 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ^ Indrapala. K,The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp. 253–54.

- ^ "Who is Ananda Krishnan?". Sunday Times. 2007-05-27. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chongkittavorn, Kavi (2007-08-06). "Asean's birth a pivotal point in history of Southeast Asia". The Nation. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ S., Muthiah (2004-08-09). "The first Madras graduate". The Hindu. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Amnesty International report on internally displaced in Sri Lanka". Amnesty International.org. 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Hunn, Deborah (2006). "Selvadurai, Shyam". glbtq.com. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Pilger, Rick. "Thoroughly Dynamic: Indira Samarasekera". University of Alberta. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (2005-04-22). "Fighting talk: She's a revolutionary's daughter and her music oozes attitude". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "NewsWatch: George Alagiah". BBC. 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Ambihaipahar, R (November 11, 1998). Scientific Pioneer: Dr. Samuel Fisk Green. Colombo: Dhulasi Publications. ISBN 955-8193-00-3.

- de Silva, C. R. (1987, 2nd ed. 1997). Sri Lanka - A History. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House. ISBN 81-259-0461-1.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - de Silva, K. M. (2005). A History of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa. ISBN 9-55-809592-3.

- Gair, James (1998). Studies in South Asian Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509521-9.

- Gunasingam, Murugar (1999). Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism:A study of its origins. Sydney: MV publications. ISBN 0-646-38106-7.

- Hudson, Dennis (January 1992). Arumuga Navalar and Hindu Renaissance amongst the Tamils (Religious Controversy in British India: Dialogues in South Asian Languages). State University of New York. ISBN 0791408272.

- Indrapala, K (2007). The evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa. ISBN 978-955-1266-72-1.

- Karthigesu, Sivathamby (1995). Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics. New Century Book House. ISBN 812340395X.

- Manogaran, Chelvadurai (2000). The untold story of the ancient Tamils of Sri Lanka. Chennai: Kumaran.

- Manogaran, Chelvadurai (1987). Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1116-X.

- Mendis, G.C. (1957, 3rd ed. 1995). Ceylon Today and Yesterday, Colombo, Lake House. ISBN 955-552-069-8

- Mortensen, Viggo (2004). Theology and the Religions: A Dialogue. Copenhagen: Wm.B. Eerdman's Publishing. ISBN 0-80-2826-74-1.

- Nadarajan, Vasantha (1999). History of Ceylon Tamils. Toronto: Vasantham.

- Pfaffenberg, Brian (1994). The Sri Lankan Tamils. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8845-7.

- Pujangga, Putra (1997). A requiem for Jaffna. London: Anantham Books. ISBN 1-902098-00-5.

- Ross, Russell (1988). Sri Lanka: A Country Study. USA: U.S. Library of Congress.

- Smith, V. A. (1958). The Oxford History of India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 01-956-1297-3.

- Spencer, Jonathan (1990). Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict. Routledge. ISBN 04-150-4461-8.

- Subramaniam, Suganthy (2006). Folk Traditions and Songs of Batticaloa District (in Tamil). Kumaran Publishing. ISBN 095494-40-5-4.

- Tambiah, H. W (2001). Laws and customs of Tamils of Jaffna (revised edition). Colombo: Women’s Education & Research Centre. ISBN 9-55-9261-16-9.

- Wilson, A.J. (2000). Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-338-0.

- Yalman, N (1967). Under the bo tree: studies in caste, kinship, and marriage in the interior of Ceylon. Berkeley: University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)