Human migration

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (November 2007) |

Human migration denotes any movement by humans from one district to another, sometimes over long distances or in large groups.

The movement of populations in modern times has continued under the form of both voluntary migration within one's region, country, or beyond, and involuntary migration (which includes the slave trade, trafficking in human beings and ethnic cleansing). People who migrate are called migrants, or, more specifically, emigrants, immigrants or settlers, depending on historical setting, circumstances and perspective.

The pressures of human migrations, whether as outright conquest or by slow cultural infiltration and resettlement, have affected the grand epochs in history (e.g. the Decline of the Roman Empire); under the form of colonization, migration has transformed the world (e.g. the prehistoric and historic settlements of Australia and the Americas). Population genetics studied in traditionally settled modern populations have opened a window into the historical patterns of migrations, a technique pioneered by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza.

Forced migration (see population transfer) has been a means of social control under authoritarian regimes, yet free initiative migration is a powerful factor in social adjustment (e.g. the growth of urban populations).

In December 2003 The Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM) was launched with the support of Kofi Annan and several countries, with an independent 19-member Commission, threefold mandate and a finite life-span, ending December 2005. Its report, based on regional consultation meetings with stakeholders and scientific reports from leading international migration experts, was published and presented to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan on 5 October 2005.[1]

Different types of migration include:

- Daily human commuting.[citation needed]

- Seasonal human migration is mainly related to agriculture.

- Permanent migration, for the purposes of permanent or long-term stays.

- Local

- Regional

- Rural to Urban, more common in developing countries as industrialization takes effect (urbanization)

- Urban to Rural, more common in developed countries due to a higher cost of urban living (suburbanization)

- International migration

Pre-modern migrations

Historical migration of human populations begins with the movement of Homo erectus out of Africa across Eurasia about a million years ago. Homo sapiens appear to have occupied all of Africa about 150,000 years ago, moved out of Africa 70,000 years ago, and had spread across Australia, Asia and Europe by 40,000 years ago. Migration to the Americas took place 20 to 15,000 years ago, and by 2,000 years ago, most of the Pacific Islands were colonized. Later population movements notably include the Neolithic Revolution, Indo-European expansion, and the Early Medieval Great Migrations including Turkic expansion.

This evidence indicates that the ancestors of the Austronesians' spread from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan at some time around 8,000 years ago. Evidence from historical linguistics suggests that it is from this island that seafaring peoples migrated, perhaps in distinct waves separated by millennia, to the entire region encompassed by the Austronesian languages. It is believed that this migration began around 6,000 years ago.[2] Indo-Aryan migration to and within Northern India is consequently presumed to have taken place in the Middle to Late Bronze Age, contemporary to the Late Harappan phase in India (ca. 1700 to 1300 BC). From 180 BC, a series of invasions from Central Asia followed, including those led by the Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians, Indo-Parthians and Kushans in the north-western Indian subcontinent.[3][4][5]

From about 750 BC the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies in all directions. In Europe two waves of migrations dominate demographic distributions, that of the Celtic people, and the later Migration Period from the east. Other examples are small movements like ancient Scots moving from Hibernia to Caledonia and Magyars into Pannonia (modern-day Hungary). Turkic peoples spread across most of Central Asia into Europe and the Middle East between the 6th and 11th centuries. Recent research suggests that the Madagascar was uninhabited until Malay seafarers from Indonesia arrived during the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. Subsequent migrations from both the Pacific and Africa further consolidated this original mixture, and Malagasy people emerged.[6]

Before the expansion of the Bantu languages and their speakers, the southern half of Africa is believed to have been populated by Pygmies and Khoisan speaking people, today occupying the arid regions around the Kalahari Desert and the forest of Central Africa. By about 1000 AD Bantu migration had reached modern day Zimbabwe and South Africa. The Banu Hilal and Banu Ma'qil were a collection of Arab Bedouin tribes from the Arabian Peninsula who migrated westwards via Egypt between the 11th and 13th centuries. Their migration strongly contributed to the arabization and islamization of the western Maghreb, which was until then dominated by Berber tribes. Ostsiedlung was the medieval eastward migration and settlement of Germans. The 13th century was the time of the great Mongol and Turkic migrations across Eurasia.[7]

Between the 11th and 18th centuries, the Vietnamese expanded southward in a process known as nam tiến (southward expansion).[8] Manchuria was separated from China proper by the Inner Willow Palisade, which restricted the movement of the Han Chinese into Manchuria during the Qing Dynasty, as the area was off-limits to the Han until the Qing started colonizing the area with them later on in the dynasty's rule.[9]

The Age of Exploration and European Colonialism led to an accelerated pace of migration since Early Modern times. In the 16th century perhaps 240,000 Europeans entered American ports.[10] In the 19th century over 50 million people left Europe for the Americas.[11] The local populations or tribes, such as the Aboriginal people in Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Japan[12] and the United States, were usually far overwhelmed numerically by the settlers. More recent examples are the movement of ethnic Chinese into Tibet and Eastern Turkestan[13], ethnic Javanese into Western New Guinea and Kalimantan[14] (see Transmigration program), Brazilians into Amazonia[15], Israelis into the West Bank and Gaza, ethnic Arabs into Iraqi Kurdistan, and ethnic Russians into Siberia and Central Asia.[16]

Modern Migrations

Industrialization

While the pace of migration had accelerated since the 18th century already (including the involuntary slave trade), it would increase further in the 19th century. Manning distinguishes three major types of migration: labor migration, refugee migrations, and, lastly, urbanization. Millions of agricultural workers left the countryside and moved to the cities causing unprecedented levels of urbanization. This phenomenon began in Britain in the late 18th century and spread around the world and continues to this day in many areas.

Industrialization encouraged migration wherever it appeared. The increasingly global economy globalized the labor market. Atlantic slave trade diminished sharply after 1820, which gave rise to self-bound contract labor migration from Europe and Asia to plantations. Also overpopulation[citation needed], open agricultural frontiers and rising industrial centers attracted voluntary, encouraged and sometimes coerced migration. Moreover, migration was significantly eased by improved transportation techniques.

Transnational labor migration reached a peak of three million migrants per year in the early twentieth century. Italy, Norway, Ireland and the Quongdong region of China were regions with especially high emigration rates during these years. These large migration flows influenced the process of nation state formation in many ways. Immigration restrictions have been developed, as well as diaspora cultures and myths that reflect the importance of migration to the foundation of certain nations, like the American melting pot. The transnational labor migration fell to a lower level from 1930s to the 1960s and then rebounded.

The United States experienced considerable internal migration related to industrialization, including its African American population. From 1910–1970, approximately 7 million African Americans migrated from the rural Southern United States, where blacks faced both poor economic opportunities and considerable political and social prejudice, to the industrial cities of the Northeast, Midwest and West where relatively well paid jobs were available.[17] This phenomenon came to be known in the United States as its own Great Migration.

The twentieth century experienced also an increase in migratory flows caused by war and politics. Muslims moved from the Balkan to Turkey, while Christians moved the other way, during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. 400,000 Jews moved to Palestine in the early twentieth century. The Russian Civil War caused some 3 million Russians, Poles and Germans to migrate out of the Soviet Union. World War II and decolonization also caused migrations, see below.

sources:

Patrick Manning, Migration in World History (2005) p 132-162.

Adam McKeown, 'Global migration, 1846-1940' in: Journal of Global History (June 2004).

World War II

See World War II evacuation and expulsion and Population transfer in the Soviet Union for World War II forced migrations.

The Jewish across Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East formed from voluntary migrations, enslavement, threats of enslavement and pogroms. After the Nazis brought the Holocaust upon Jewish people in the 1940s, there was increased migration to the British Mandate of Palestine, which became the modern day state of Israel as a result of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.

Provisions of the Potsdam Agreement from 1945 signed by victorious Western Allies and the Soviet Union led to one of the largest European migrations, and definitely the largest in the 20th century. It involved the migration and resettlement of close to or over 20 million people. The largest affected group were 16.5 million Germans expelled from Eastern Europe westwards. The second largest group were Poles, millions of whom were expelled westwards from eastern Kresy region and resettled in the so-called Recovered Territories (see Allies decide Polish border in the article on the Oder-Neisse line). Hundreds of thousands of Poles, Ukrainians (Operation Wisła), Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians and some Belarusians, were in the meantime expelled eastwards from Europe to the Soviet Union. Finally, many of the several hundred thousand Jews remaining in the Eastern Europe after the Holocaust migrated outside Europe to Israel.

Contemporary migration

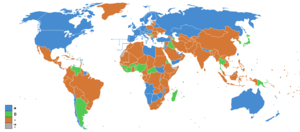

Target regions with currently high immigration rates are North America, Australia, Europe (except eastern Europe), and the Russian Federation. [1]

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: 1.0% per year

- Burundi: 0.8%

- Jordan: 0.63%

- Canada: 0.48%

- Ireland: 0.48%

- Argentina: 0.9%

- Australia: 0.38%

- New Zealand: 0.36%

- Angola: 0.35%

- Portugal: 0.34%

- USA: 0.32%

- Switzerland: 0.31%

- Netherlands: 0.27%

- Denmark: 0.25%

- Belarus: 0.23%

- Greece: 0.23%

- Germany[18]: 0.92%

- United Kingdom: 0.22%

- Italy: 0.82%

Small countries like island states can have extremely high migration rates that fluctuate over short times due to their low overall population: Micronesia -2% per year, Grenada -1.6%, Samoa -1.2%, Dominica -0.93%, Suriname and Virgin Islands -0.87%, Greenland -0.83%, Guyana and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines -0.75%; Liberia 2.7%, Kuwait 1.6%, Turks and Caicos Islands 1.1%, San Marino 1.1%.

For more data on contemporary migration see:

Migrations and climate cycles

The modern field of climate history suggests that the successive waves of Eurasian nomadic movement throughout history have had their origins in climatic cycles, which have expanded or contracted pastureland in Central Asia, especially Mongolia and the Altai. People were displaced from their home ground by other tribes trying to find land that could be grazed by essential flocks, each group pushing the next further to the south and west, into the highlands of Anatolia, the plains of Hungary, into Mesopotamia or southwards, into the rich pastures of China.

Toward an understanding of migration

Types of migrations

- The cyclic movement which involves commuting,and a seasonal movement, and nomadism.

- The periodic movement which consists of migrant labor, military service, and pastoral farming Transhumance.

- The migratory movement that moves from the eastern part of the US to the western part. It also moves from China to southeast Asia, from Europe to North America, and from South America to the middle part of the Americas.

- Rural exodus, migration from rural areas to the cities

Ravenstein's 'laws of migration'

Certain laws of social science have been proposed to describe human migration. The following was a standard list after Ravenstein's proposals during the time frame of 1834 to 1913. The laws are as follows:

- every migration flow generates a return or countermigration.

- the majority of migrants move a short distance.

- migrants who move longer distances tend to choose big-city destinations

- urban residents are less migratory than inhabitants of rural areas.

- families are less likely to make international moves than young adults.

Other migration models

- Migration occurs because individuals search for food, sex and security outside their usual habitation.(Idyorough, 2008)

- Zipf's Inverse distance law (1956)

- Gravity model of migration and the Friction of distance

- Buffer Theory

- Stouffer's Theory of intervening opportunities (1940)

- Lee's Push-pull theory (1967)

- Zelinsky's Mobility Transition Model (1971)

- Bauder's Regulation of labor markets (2006) "suggests that the international migration of workers is necessary for the survival of industrialized economies...[It] turns the conventional view of international migration on its head: it investigates how migration regulates labor markets, rather than labor markets shaping migration flows." (from the book description)

Causes of migrations

Causes of migrations have modified over hundreds of years. Some cases are constant, some of them do not carry the same importance as years ago (for example: in 18th and 19th centuries labor migration did not have the same character like today).

In general we can divide factors causing migrations into two groups of factors: Push and pull factors. In general:

- Push Factors are economic, political, cultural, and environmentally based.

- Pull Factors are economic, political, cultural, and environmentally based.

- Barriers/Obstacles which is an example of Nigeria in the 1970s and 1980s.

Some certain factors are both push and pull like education, industry etc.

On the macro level, the causes of migration can be distilled into two main categories: security dimension of migration (natural disasters, conflicts, threats to individual safety, poor political prospects) and economic dimension of migration (poor economic situation, poor situation of national market). [AIV document]

Push and Pull Factors

This article possibly contains original research. (February 2008) |

Push and pull factors are those factors which either forcefully push people into migration or attract them. A push factor is forceful, and a factor which relates to the country from which a person migrates. It is generally some problem which results in people wanting to migrate. Different types of push factors can be seen further below. A push factor is a flaw or distress that drives a person away from a certain place. A pull factor is something concerning the country to which a person migrates. It is generally a benefit that attracts people to a certain place. Push and pull factors are usually considered as north and south poles on a magnet. Push Factors

- Not enough jobs

- Few opportunities

- "Primitive" conditions

- Desertification

- Famine/drought

- Political fear/persecution

- Poor medical care

- Loss of wealth

- Natural Disasters

- Death threats

- Slavery

- Pollution

- Poor housing

- Landlords

- Bullying

- Poor chances of finding courtship

Pull Factors

- Job opportunities

- Better living conditions

- Political and/or religious freedom

- Enjoyment

- Education

- Better medical care

- Security

- Family links

- Industry

- Better chances of finding courtship

Effects of migration

Migration like any other process shapes many fields of life, having both advantages and disadvantages. Effects of migrations are:

- changes in population distribution

- demographic consequences: since migration is selective of particular age groups, migrants are mostly young and in productive age. It can cause a demographic crisis – population ageing, what in turn can be followed by economic problems (shrinking group of economically active population has to finance extending group of inactive population).

- economic results, which are of the greatest importance for the development of the countries.

Migration has had a significant effect on world geography.

- It has contributed to the evolution and development of separate cultures.

- It has contributed to the diffusion of cultures by interchange and communication.

- It has contributed to the complex mix of people and cultures found in different regions of the world today

Migration in the European Union

The wages in the Western Europe are generally higher than the rest of Europe- thus explaining why a large number of Eastern Europeans choose to migrate to Western Europe.

For more information go to:

- OECD International Migration Data 2006

- Net Human Migration Rate in OECD Countries

- Inflows of asylum seekers into OECD countries

Migration patterns in India

Estimates based on industry sectors mainly employing migrants suggest that there are around 100 million circular migrants in India. Caste, social networks and historical precedents play a powerful role in shaping patterns of migration. Migration for the poor is mainly circular, as despite moving temporarily to urban areas, they lack the social security which might keep them there more permanently. They are also keen to maintain a foothold in home areas during the agricultural season.

Research by the Overseas Development Institute identifies a rapid movement of labour from slower to faster growing parts of the economy. Migrants can often find themselves excluded by urban housing policies and migrant support initiatives are needed to give workers improved access to market information, certification of identity, housing and education.[19]

See also

- Emigration

- Existential migration

- Population mobility

- Globalization

- List of diasporas

- Most recent common ancestor

- Migrant literature

- Snowbird (people)

- Separation barrier

- Settler colonialism

Further information

Literature

Books

- Bauder, Harald Labor Movement: How Migration Regulates Labor Markets, New York: Oxford University Press 2006

- Behdad, Ali, A Forgetful Nation: On Immigration and Cultural Identity in the United States, Duke UP 2005

- Fell, Peter and Hayes, Debra, "What are they doing here? A critical guide to asylum and immigration." Birmingham (UK): Venture Press 2007.

- Hoerder, Dirk Cultures in Contact. World Migrations in the Second Millennium, Duke University Press 2002

- Knörr, Jacqueline Women and Migration. Anthropological Perspectives, Frankfurt & New York: Campus Verlag & St. Martin's Press 2000.

- Knörr, Jacqueline Childhood and Migration. From Experience to Agency, Bielefeld: Transcript 2005

- Manning, Patrick Migration in World History, New York and London: Routledge 2005

- Migration for Employment Paris: OECD Publications, 2004.

- OECD International Migration Outlook 2007, Paris: OECD Publications, 2007

- Abdelmalek Sayad, The Suffering of the Immigrant, Preface by Pierre Bourdieu, Polity Press 2004

- Stalker, Peter, No-Nonsense Guide to International Migration, New Internationalist, second edition, 2008.

Journals

- International Migration Review

- Migration Letters

Online Books

- OECD International Migration Outlook 2007 (subscription service)

Online Databases

Documentary films

- The Short Life of José Antonio Gutierrez

- El Inmigrante, Directors: David Eckenrode, John Sheedy, John Eckenrode. 2005. 90 min. (U.S./Mexico)

External links

- Current Migration Research; short articles

- Migration patterns of early Humans and the full size map

- Migration Heritage route : Luxembourg

- Pictures of Refugees in Europe - Features by Jean-Michel Clajot, Belgian photographer

- : Presentation of the Human Migrations Documentation Center that coordinates the European Week of Migration Heritage, 2007

- European Institute of Cultural Routes : Presentation of the Migration Heritage Route in Europe,2005

- Migration News

- Metropolitan Museum page on Lapita culture

- Michael Haerdter Remarks on modernity, mobility, nomadism and the arts

- An mtDNA view of the peopling of the world by Homo sapiens

- National Geographic: Atlas of the Human Journey (Haplogroup-based human migration maps)

- Journey of Mankind : the Peopling of the World

- Stalker's Guide to International Migration Comprehensive interactive guide, with map and statistics

- Diplomacy Monitor - Migration

- Global Culture: essays on migration and globalization

- Snapshot: Global Migration: "Nearly 190 million people, about three percent of the world's population, lived outside their country of birth in 2005. A look at the flow of people around the globe." Flash graphic with tabs showing Net flow, Share of total migrants, Share of local population, Money sent home by migrants and Money sent home as a share of GDP. (New York Times, June 22, 2007)

- NSW Migration Heritage Centre, Australia

- Metropolis Project

- International Organization for Migration

- IMISCOE-International migration, integration and social cohesion

- IMES-Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies

- International Organization for Migration

- Migrationonline.cz - Website on Human Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

- Qantara-Dossier: Migration in Germany

Notes

- ^ The 90-page Report, along with supporting evidence, is available on the GCIM website gcim.org

- ^ Language trees support the express-train sequence of Austronesian expansion, Nature

- ^ The appearance of Indo-Aryan speakers, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Trivedi, Bijal P (2001-05-14). "Genetic evidence suggests European migrants may have influenced the origins of India's caste system". Genome News Network. J. Craig Venter Institute. Retrieved 2005-01-27.

{{cite news}}: line feed character in|title=at position 64 (help) - ^ Genetic Evidence on the Origins of Indian Caste Populations -- Bamshad et al. 11 (6): 994, Genome Research

- ^ Malagasy languages, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ Migrations-&-World History

- ^ The Le Dynasty and Southward Expansion

- ^ From Ming to Qing

- ^ "The Colombian Mosaic in Colonial America" by James Axtell

- ^ David Eltis Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic slave trade

- ^ Report on a New Policy for the Ainu: A Critique

- ^ China given warning on Xinjiang

- ^ Ethnic violence continues to rage in Central Kalimantan

- ^ Scientists demand Brazil suspend Amazon colonization project

- ^ Robert Greenall, Russians left behind in Central Asia, BBC News, 23 November 2005.

- ^ Great Migration, accessed 12/7/2007

- ^ Immigration to Germany – A Decade in Review Federal Ministry of the Interior, Germany

- ^ "Support for migrant workers: the missing link in India's development?" (PDF). Overseas Development Institute. September 2008.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Erectus Ahoy