Tiger shark

| Tiger Shark Temporal range: Early Eocene to Present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Galeocerdo |

| Species: | G. cuvier

|

| Binomial name | |

| Galeocerdo cuvier | |

| |

| Tiger shark range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Squalus cuvier Peron and Lessueur, 1822 | |

Template:Sharksportal The tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier, the second largest predatory shark (after the great white shark) is the only member of the genus Galeocerdo. Mature sharks average 3.25 to 4.25 m (11 to 14 ft) long[3][4] and weigh 385 to 635 kilograms (849 to 1,400 lb)[3]. It is found in many of the tropical and temperate regions of the world's oceans, and is especially common around islands in the central Pacific. This shark is a solitary hunter, usually hunting at night. Its name is derived from the dark stripes down its body, which fade as the shark matures.

The tiger shark is a predator, known for eating a wide range of items. Its usual diet consists of fish, seals, birds, smaller sharks, squid, turtles, and dolphins. It has sometimes been found with man-made waste such as license plates or pieces of old tires in its digestive tract and is often referred to as "the wastebasket of the sea".

A tiger shark may be easily identified due to its dark stripes which are similar to a tiger pattern. It also has dorsal fins that are distinctively close to its tail. These sharks are often large in size and may encounter humans because they often visit shallow reefs, harbours and canals.

The tiger shark is second only to the great white shark, coming close to the bull shark in number of recorded attacks on humans[5] and is considered, along with the great white, bull shark, and the oceanic whitetip shark to be one of the sharks most dangerous to humans.[6] This may be due to its aggressive nature and frequency of human contact as it often inhabits populated waters such as Hawaiian beaches.

Taxonomy

The shark was first described by Peron and Lessueur in 1822 and was given the name Squalus cuvier.[7] Müller and Henle, in 1837 renamed it Galeocerdo tigrinus.[3] The genus, Galeocerdo, is derived from the Greek, galeos which means shark and the Latin cerdus which means the hard hairs of pigs.[3] It is often colloquially called the man-eater shark.[3]

The tiger shark is a member of the order Carcharhiniformes;[7] members of this order are characterized by the presence of a nictitating membrane over the eyes, two dorsal fins, an anal fin, and five gill slits. It is the largest member of the Carcharhinidae family, commonly referred to as requiem sharks. This family includes some other well-known sharks such as the blue shark, lemon shark and bull shark.

Distribution and habitat

The tiger shark is often found close to the coast, in mainly tropical and sub-tropical waters, though they can reside in temperate waters. Tiger sharks are the second largest predatory shark other than the great white.[3] The shark's behavior is primarily nomadic, but is guided by warmer currents, and it stays closer to the equator throughout the colder months. The shark tends to stay in deep waters that line reefs but does move into channels to pursue prey in shallower waters. In the western Pacific Ocean, the shark has been found as far north as Japan and as far south as New Zealand.[8]

The shark has been recorded down to a depth just shy of 900 metres (3,000 ft)[3] but is also known to move into shallow water - water that would normally be considered too shallow for a species of its size. It is also frequent creatures, allowing them to hunt in darkness. In addition, the tiger shark, like many other sharks, has a reflective layer behind the retina called tapetum lucidum which allows light-sensing cells a second chance to capture photons of visible light, enhancing vision in low light condition. A tiger shark generally has long fins and a long upper tail; the long fins act like wings and provide lift as the shark maneuvers through water, whereas the long tail provides bursts of speed. A tiger shark normally swims using little movements of its body. Its high back and dorsal fin act as a pivot, allowing it to spin quickly on its axis.

Its teeth are highly specialized to slice through flesh, bone, and other tough substances such as the shells of sea turtles, and unusually among sharks, its upper and lower teeth have dissimilar shapes. Like most sharks, however, tiger shark teeth are continually replaced by rows of replacements from within its jaws.

Diet

The tiger shark, which generally hunts at night, has a reputation for eating anything it has access to, ignoring what nutritional value the prey may or may not hold.[3] Apart from what is thought to be sporadic feeding, its most common foods include: common fish, squid, birds, seals, dugongs, other sharks, and sea turtles.[3] The shark has a number of features which make it a good hunter, such as excellent eyesight, which allows for access to murkier waters which can offer more varieties of prey and its acute sense of smell which enable it to react to faint traces of blood in its waters and is able to follow them to the source. The tiger shark's ability to pick up on low-frequency pressure waves produced by the movements of swimming animals, for example the thrashing of an injured animal, enables the shark to find a variety of prey.

The shark is known to be aggressive. The ability to pick up low-frequency pressure waves enables the shark to advance towards an animal with confidence, even in the environment of murky water where it is often found.[9] The shark is known to circle its prey and even study it by prodding it with its snout.[9] When attacking the shark devours all of its prey.[9] Because of its aggressive nature of feeding, it is common to find a variety of foreign objects inside the digestive tract of a tiger shark. Some examples of more unusual items are automobile number plates, petroleum cans, tires, suits of armour, and baseballs. For this reason, the tiger shark is often regarded as the ocean's garbage can.[10]

Reproduction

A male Tiger shark reaches sexual maturity at 2.3 to 2.9 metres (7.5 to 9.5 ft) and females at 2.5 to 3.5 metres (8.2 to 11.5 ft).[4] The female tiger shark mates once every 3 years.[10] They breed by internal fertilization. It is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed. The male tiger shark will insert one of his claspers into the female's genital opening (cloaca), acting as a guide for the sperm to be introduced. The male uses its teeth to hold the female still during the procedure, often causing the female considerable discomfort. Mating in the northern hemisphere will generally take place between the months of March and May, with the young being born around April or June the following year. In the southern hemisphere, mating takes place in November, December, or early January.[3]

The young are nourished inside the mother's body for up to 16 months, where the female can produce a litter ranging from 10 to 80 pups.[3] A newborn tiger shark is generally 51 centimetres (20 in) to 76 centimetres (30 in) long[3] and leaves its mother upon birth. It is unknown how long tiger sharks live, but they can live longer than 12 years.[10]

Dangers and conservation

Although shark attacks on humans are a relatively rare phenomenon, the tiger shark is responsible for a large percentage of the fatal attacks that do occur on humans, and is regarded as one of the most dangerous species of sharks.[11][5] Tiger sharks reside in temperate and tropical waters. They are often found in river estuaries and harbours, as well as shallow water close to shore, where they are bound to come into contact with humans. Tiger sharks are known to dwell in waters with runoff, such as where a river enters the ocean.[4][3]

Tiger sharks are considered to be sacred in Hawaiinā ʻaumākua (ancestor spirits) by the native Hawaiians, however between 1959 and 1976, 4,668 tiger sharks were hunted down in an effort to control what was proving to be detrimental to the tourism industry. Despite these numbers, little decrease was ever detected in the attacks on humans. It is illegal to feed sharks in Hawaii and any interaction with them such as cage diving is discouraged.[12] However, South African shark scientist Mark Addison demonstrated that the sharks could be tamed somewhat in a 2007 Discovery Channel special.[13]

While the tiger shark is not directly commercially fished, it is caught for its fins, flesh, liver, which is a valuable source of vitamin A used in the production of vitamin oils, and distinct skin, as well as by big game fishers.[3]

See also

- List of sharks

- List of prehistoric cartilaginous fish

- List of fatal, unprovoked shark attacks in the United States by decade

References

- ^ Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera (Chondrichthyes entry)". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

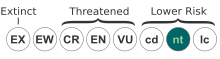

- ^ Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is near threatened

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Tiger Shark Biological Profile". Florida Museum of Natural History Icthyology Department. Retrieved 2005-01-22.

- ^ a b c "Galeocerdo cuvier Tiger Shark". Marine Bio. Retrieved 2006-10-14.

- ^ a b "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History University of Florida. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ Daley, Audrey (1994). Shark. Hodder & Stroughton. ISBN 0-340-61654-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Unknown parameter|ISBN status=ignored (help) - ^ a b "ITIS report, Galeocerdo cuvier". Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- ^ "Galeocerdo cuvier". Fishbase. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ^ a b c "Tiger Shark". ladywildlife.com. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ^ a b c Ritter, Erich K. (15 Dec 1999). "Fact Sheet: Tiger Sharks". Shark Info. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ Ritter, Erich K. "Which shark species are really dangerous?". Shark Info. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ "Federal Fishery Managers Vote To Prohibit Shark Feeding" (PDF). Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "Shark Week: 'Deadly Stripes: Tiger Sharks'". LA Times. 2007-07-30. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- General references

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2005). "Galeocerdo cuvier" in FishBase. March 2005 version.

- "Galeocerdo cuvier". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 7 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - Tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier at marinebio.org

- "Tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- General information Enchanted Learning. Retrieved January 22, 2005.

- Different diet information Shark Info. Retrieved January 22, 2005.

- Tiger sharks in Hawaii Research program. Retrieved January 22, 2005.