Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletos (Θαλής ο Μιλήσιος) | |

|---|---|

| School | Ionian Philosophy, Milesian school, Naturalism |

Main interests | Ethics, Metaphysics, Mathematics, Astronomy |

Notable ideas | Water is the physis, Thales' theorem |

Thales of Miletus (Θαλῆς ὁ Μιλήσιος (Template:PronEng or "THEH-leez") , ca. 624 BC–ca. 546 BC), was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Miletus in Asia Minor, and one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard him as the first philosopher in the Greek tradition.[1] According to Bertrand Russell, "Philosophy begins with Thales."[2]

Life

Thales lived around the mid 620s–547 BC and was born in the city of Miletus. Miletus was an ancient Greek Ionian city on the western coast of Asia Minor (in what is today the Aydin Province of Turkey) near the mouth of the Maeander River.

Background

The dates of Thales' life are not known precisely. The time of his life is roughly established by a few dateable events mentioned in the sources and an estimate of his length of life. According to Herodotus, Thales once predicted a solar eclipse which has been determined by modern methods to have been on May 28, 585 BC.[3] Diogenes Laërtius quotes the chronicle of Apollodorus as saying that Thales died at 78 in the 58th Olympiad, and Sosicrates as reporting that he was 90 at his death.

As mentioned, according to tradition, Thales was born in Miletus, Asia Minor. Diogenes Laertius states that ("according to Herodotus and Douris and Democritus") his parents were Examyes and Cleobuline, Phoenician nobles. Giving another opinion, he ultimately connects Thales' family line back to Phoenician prince Cadmus. Diogenes also reports two other stories, one that he married and had a son, Cybisthus or Cybisthon, or adopted his nephew of the same name. The second is that he never married, telling his mother as a young man that it was too early to marry, and as an older man that it was too late. A much earlier source - Plutarch - tells the following story: Solon who visited Thales asked him the reason which kept him single. Thales answered that he did not like the idea of having to worry about children. Nevertheless, several years later Thales anxious for family adopted his nephew Cybisthus.

Thales involved himself in many activities, taking the role of an innovator. Some say that he left no writings, others that he wrote "On the Solstice" and "On the Equinox". Neither have survived. Diogenes Laërtius quotes letters of Thales to Pherecydes and Solon, offering to review the book of the former on religion, and offering to keep company with the latter on his sojourn from Athens. Thales identifies the Milesians as Athenians.[4]

Politics

Thales’ political life had mainly to do with the involvement of the Ionians in the defense of Anatolia against the growing power of the Persians, who were then new to the region. A king had come to power in neighboring Lydia, Croesus, who was somewhat too aggressive for the size of his army. He had conquered most of the states of coastal Anatolia, including the cities of the Ionians. The story is told in Herodotus.[5]

The Lydians were at war with the Medes, a remnant of the first wave of Iranians in the region, over the issue of refuge the Lydians had given to some Scythian soldiers of fortune inimical to the Medes. The war endured for five years, but in the sixth an eclipse of the sun (mentioned above) spontaneously halted a battle in progress (the Battle of Halys).

It seems that Thales had predicted this solar eclipse. The Seven Sages were most likely already in existence, as Croesus was also heavily influenced by Solon of Athens, another sage. Whether Thales was present at the battle is not known, nor are the exact terms of the prediction, but based on it the Lydians and Medes made peace immediately, swearing a blood oath.

The Medes were dependencies of the Persians under Cyrus. Croesus now sided with the Medes against the Persians and marched in the direction of Iran (with far fewer men than he needed). He was stopped by the river Halys, then unbridged. This time he had Thales with him, perhaps by invitation. Whatever his status, the king gave the problem to him, and he got the army across by digging a diversion upstream so as to reduce the flow, making it possible to ford the river. The channels ran around both sides of the camp.

The two armies engaged at Pteria in Cappadocia. As the battle was indecisive but paralyzing to both sides, Croesus marched home, dismissed his mercenaries and sent emissaries to his dependents and allies to ask them to dispatch fresh troops to Sardis. The issue became more pressing when the Persian army showed up at Sardis. Diogenes Laertius[6] tells us that Thales gained fame as a counsellor when he advised the Milesians not to engage in a symmachia, a “fighting together”, with the Lydians. This has sometimes been interpreted as an alliance, but a ruler does not ally with his subjects.

Croesus was defeated before the city of Sardis by Cyrus, who subsequently spared Miletus because it had taken no action. The Great King was something of a philosopher himself. He was so impressed by Croesus’ wisdom and his connection with the sages that he spared him and took his advice on various matters.

The Ionians were now free. Herodotus says that Thales advised them to form an Ionian state; that is, a bouleuterion (“deliberative body”) to be located at Teos in the center of Ionia. The Ionian cities should be demoi, or “districts”. Miletus, however, received favorable terms from Cyrus. The others remained in an Ionian League of 12 cities (excluding Miletus now), and were subjugated by the Persians.

Chris brown is hot

Sagacity

Diogenes Laertius[7] tells us that the Seven Sages were created in the archonship of Damasius at Athens about 582 BC and that Thales was the first sage. The same story, however, asserts that Thales emigrated to Miletus. There is also a report that he did not become a student of nature until after his political career. Much as we would like to have a date on the seven sages, we must reject these stories and the tempting date if we are to believe that Thales was a native of Miletus, predicted the eclipse, and was with Croesus in the campaign against Cyrus.

Thales had instruction from Egyptian priests, we are told. It was fairly certain that he came from a wealthy and established family, and the wealthy customarily educated their children. Moreover, the ordinary citizen, unless he was a seafaring man or a merchant, could not afford the grand tour in Egypt, and in any case did not consort with noble lawmakers such as Solon.

He did participate in some games, most likely Panhellenic, at which he won a bowl twice. He dedicated it to Apollo at Delphi. As he was not known to have been athletic, his event was probably declamation, and it may have been victory in some specific phase of this event that led to his being designated sage.[citation needed]

Theories

It is arguable whether the Greeks always invoked idiosyncratic explanations of natural phenomena by reference to the will of anthropomorphic gods and heroes. However, such explanations were common. Thales aimed to explain natural phenomena via a rational explanation that referenced natural processes themselves. He explained earthquakes by hypothesizing that the Earth floats on water, and that earthquakes occur when the Earth is rocked by waves.

Thales, according to Aristotle, asked what was the nature (Greek Arche) of the object so that it would behave in its characteristic way. Physis (φύσις) comes from phyein (φύειν), "to grow", related to our word "be".[8] (G)natura is the way a thing is "born",[9] again with the stamp of what it is in itself.

Aristotle[10] characterizes most of the philosophers "at first" (πρῶτον) as thinking that the "principles in the form of matter were the only principles of all things", where "principle" is arche, "matter" is hyle ("wood") and "form" is eidos.

"Principle" translates arche, but the two words do not have precisely the same meaning. A principle of something is merely prior (related to pro-) to it either chronologically or logically. An arche (from αρχειν, "to rule") dominates an object in some way. If the arche is taken to be an origin, then specific causality is implied; that is, B is supposed to be characteristically B just because it comes from A, which dominates it.

The archai that Aristotle had in mind in his well-known passage on the first Greek scientists are not necessarily chronologically prior to their objects, but are constituents of it. For example, in pluralism objects are composed of earth, air, fire and water, but those elements do not disappear with the production of the object. They remain as archai within it, as do the atoms of the atomists.

What Aristotle is really saying is that the first philosophers were trying to define the substance(s) of which all material objects are composed. As a matter of fact, that is exactly what modern scientists are trying to do in nuclear physics, which is a second reason why Thales is described as the first scientist.

Water as a first principle

Thales' most famous belief was his cosmological thesis, which held that the world started from water. Aristotle considered this belief roughly equivalent to the later ideas of Anaximenes, who held that everything in the world was composed of air.

The best explanation of Thales' view is the following passage from Aristotle's Metaphysics.[11] The passage contains words from the theory of matter and form that were adopted by science with quite different meanings.

- "That from which is everything that exists (ἅπαντα τὰ ὄντα) and from which it first becomes (ἐξ οὗ γίγνεται πρῶτου) and into which it is rendered at last (εἰς ὃ φθείρεται τελευταῖον), its substance remaining under it (τῆς μὲν οὐσίας ὑπομενούσης), but transforming in qualities (τοῖς δὲ πάθεσι μεταβαλλούσης), that they say is the element (στοιχεῖον) and principle (ἀρχήν) of things that are."

And again:

- "For it is necessary that there be some nature (φύσις), either one or more than one, from which become the other things of the object being saved... Thales the founder of this type of philosophy says that it is water."[12]

Aristotle's depiction of the change problem and the definition of substance is clear. If an object changes, is it the same or different? In either case how can there be a change from one to the other? The answer is that the substance "is saved", but acquires or loses different qualities (πάθη, the things you "experience").

A deeper dip into the waters of the theory of matter and form is properly reserved to other articles. The question for this article is, how far does Aristotle reflect Thales? He was probably not far off, and Thales was probably an incipient matter-and-formist.

The essentially non-philosophic Diogenes Laertius states that Thales taught as follows:

- "Water constituted (ὑπεστήσατο, 'stood under') the principle of all things."[13]

Heraclitus Homericus[14] states that Thales drew his conclusion from seeing moist substance turn into air, slime and earth. It seems clear that Thales viewed the Earth as solidifying from the water on which it floated and which surrounded Ocean.

Beliefs in divinity

Thales applied his method to objects that changed to become other objects, such as water into earth (he thought). But what about the changing itself? Thales did address the topic, approaching it through magnets and amber, which, when electrified by rubbing, attracts also. A concern for magnetism and electrification never left science, being a major part of it today.

How was the power to move other things without the mover’s changing to be explained? Thales saw a commonality with the powers of living things to act. The magnet and the amber must be alive, and if that were so, there could be no difference between the living and the dead. When asked why he didn’t die if there was no difference, he replied “because there is no difference.”

Aristotle defined the soul as the principle of life, that which imbues the matter and makes it live, giving it the animation, or power to act. The idea did not originate with him, as the Greeks in general believed in the distinction between mind and matter, which was ultimately to lead to a distinction not only between body and soul but also between matter and energy.

If things were alive, they must have souls. This belief was no innovation, as the ordinary ancient populations of the Mediterranean did believe that natural actions were caused by divinities. Accordingly, the sources say that Thales believed all things possessed divinities. In their zeal to make him the first in everything they said he was the first to hold the belief, which even they must have known was not true.

However, Thales was looking for something more general, a universal substance of mind. That also was in the polytheism of the times. Zeus was the very personification of supreme mind, dominating all the subordinate manifestations. From Thales on, however, philosophers had a tendency to depersonify or objectify mind, as though it were the substance of animation per se and not actually a god like the other gods. The end result was a total removal of mind from substance, opening the door to a non-divine principle of action. This tradition persisted until Einstein, whose cosmology is quite a different one and does not distinguish between matter and energy.

Classical thought, however, had proceeded only a little way along that path. Instead of referring to the person, Zeus, they talked about the great mind:

- "Thales", says Cicero,[15] "assures that water is the principle of all things; and that God is that Mind which shaped and created all things from water."

The universal mind appears as a Roman belief in Virgil as well:

- "In the beginning, SPIRIT within (spiritus intus) strengthens Heaven and Earth,

- The watery fields, and the lucid globe of Luna, and then --

- Titan stars; and mind (mens) infused through the limbs

- Agitates the whole mass, and mixes itself with GREAT MATTER (magno corpore)"[16]

Geometry

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

Thales was known for his innovative use of geometry. His understanding was theoretical as well as practical. For example, he said:

- Megiston topos: hapanta gar chorei (Μέγιστον τόπος· άπαντα γαρ χωρεί)

- ”Space is the greatest thing, as it contains all things”

Topos is in Newtonian-style space, since the verb, chorei, has the connotation of yielding before things, or spreading out to make room for them, which is extension. Within this extension, things have a position. Points, lines, planes and solids related by distances and angles follow from this presumption.

Thales understood similar triangles and right triangles, and what is more, used that knowledge in practical ways. The story is told in DL (loc. cit.) that he measured the height of the pyramids by their shadows at the moment when his own shadow was equal to his height. A right triangle with two equal legs is a 45-degree right triangle, all of which are similar. The length of the pyramid’s shadow measured from the center of the pyramid at that moment must have been equal to its height.

This story reveals that he was familiar with the Egyptian seqt, or seked, defined by Problem 57 of the Rhind papyrus as the ratio of the run to the rise of a slope, which is currently the cotangent function of trigonometry. It characterizes the angle of rise.

Our cotangents require the same units for run and rise, but the papyrus uses cubits for rise and palms for run, resulting in different (but still characteristic) numbers. Since there were 7 palms in a cubit, the seqt was 7 times the cotangent.

To use an example often quoted in modern reference works, suppose the base of a pyramid is 140 cubits and the angle of rise 5.25 seqt. The Egyptians expressed their fractions as the sum of fractions, but the decimals are sufficient for the example. What is the rise in cubits? The run is 70 cubits, 490 palms. X, the rise, is 490 divided by 5.25 or 93 1/3 cubits. These figures sufficed for the Egyptians and Thales. We would go on to calculate the cotangent as 70 divided by 93 1/3 to get 3/4 or .75 and looking that up in a table of cotangents find that the angle of rise is a few minutes over 53 degrees.

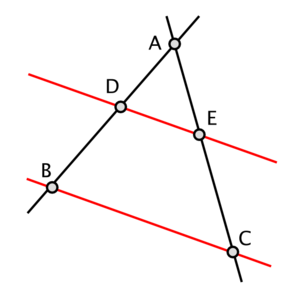

Whether the ability to use the seqt, which preceded Thales by about 1000 years, means that he was the first to define trigonometry is a matter of opinion. More practically Thales used the same method to measure the distances of ships at sea, said Eudemus as reported by Proclus (“in Euclidem”). According to Kirk & Raven (reference cited below), all you need for this feat is three straight sticks pinned at one end and knowledge of your altitude. One stick goes vertically into the ground. A second is made level. With the third you sight the ship and calculate the seqt from the height of the stick and its distance from the point of insertion to the line of sight.

The seqt is a measure of the angle. Knowledge of two angles (the seqt and a right angle) and an enclosed leg (the altitude) allows you to determine by similar triangles the second leg, which is the distance. Thales probably had his own equipment rigged and recorded his own seqts, but that is only a guess.

Thales’ Theorem is stated in another article. (Actually there are two theorems called Theorem of Thales, one having to do with a triangle inscribed in a circle and having the circle's diameter as one leg, the other theorem being also called the intercept theorem.) In addition Eudemus attributed to him the discovery that a circle is bisected by its diameter, that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal and that vertical angles are equal. It would be hard to imagine civilization without these theorems.

It is possible, of course, to question whether Thales really did discover these principles. On the other hand, it is not possible to answer such doubts definitively. The sources are all that we have, even though they sometimes contradict each other.

(The most we can say is that Thales knew these principles. There is no evidence for Thales discovering these principles, and, based on the evidence, we cannot say that Thales discovered these principles.)

Interpretations

In the long sojourn of philosophy on the earth there has existed hardly a philosopher or historian of philosophy who did not mention Thales and try to characterize him in some way. He is generally recognized as having brought something new to human thought. Mathematics, astronomy and medicine already existed. Thales added something to these different collections of knowledge to produce a universality, which, as far as writing tells us, was not in tradition before, but resulted in a new field, science.

Ever since, interested persons have been asking what that new something is. Answers fall into (at least) two categories, the theory and the method. Once an answer has been arrived at, the next logical step is to ask how Thales compares to other philosophers, which leads to his classification (rightly or wrongly).

Theory

The most natural epithets of Thales are "materialist" and "naturalist", which are based on ousia and physis. The Catholic Encyclopedia goes so far as to call him a physiologist, a person who studied physis, despite the fact that we already have physiologists. On the other hand, he would have qualified as an early physicist, as did Aristotle. They studied corpora, "bodies", the medieval descendants of substances.

Most agree that Thales' stamp on thought is the unity of substance, hence Bertrand Russell:[17]

- "The view that all matter is one is quite a reputable scientific hypothesis."

- "...But it is still a handsome feat to have discovered that a substance remains the same in different states of aggregation."

Russell was only reflecting an established tradition; for example, Nietzsche, in his Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, wrote:[18]

- "Greek philosophy seems to begin with an absurd notion, with the proposition that water is the primal origin and the womb of all things. Is it really necessary for us to take serious notice of this proposition? It is, and for three reasons. First, because it tells us something about the primal origin of all things; second, because it does so in language devoid of image or fable, and finally, because contained in it, if only embryonically, is the thought, 'all things are one.'"

This sort of materialism, however, should not be confused with deterministic materialism. Thales was only trying to explain the unity observed in the free play of the qualities. The arrival of uncertainty in the modern world made possible a return to Thales; for example, John Elof Boodin writes ("God and Creation"):

- "We cannot read the universe from the past..."

Boodin defines an "emergent" materialism, in which the objects of sense emerge uncertainly from the substrate. Thales is the innovator of this sort of materialism.

Method

Thales represents something new in method as well. Edmund Husserl[19] attempts to capture it as follows. Philosophical man is a new cultural configuration based on a rejection of tradition in favor of an inquiry into what is true in itself; that is, an ideal of truth. It begins with isolated individuals such as Thales, but they are supported and cooperated with as time goes on. Finally the ideal transforms the norms of society, leaping across national borders.

Classification

The term, Pre-Socratic, derives ultimately from Aristotle, a qualified philosopher ("the father of philosophy"), who distinguished the early philosophers as concerning themselves with substance.

Diogenes Laertius on the other hand took a strictly geographic and ethnic approach. Philosophers were either Ionian or Italian. He used Ionian in a broader sense, including also the Athenian academics, who were not Pre-Socratics. From a philosophic point of view, any grouping at all would have been just as effective. There is no basis for an Ionian or Italian unity. Some scholars, however, concede to Diogenes' scheme as far as referring to an "Ionian" school. There was no such school in any sense.

The most popular approach refers to a Milesian school, which is more justifiable socially and philosophically. They sought for the substance of phenomena and may have studied with each other. Some ancient writers qualify them as Milesioi, "of Miletus."

Influence on others

Thales had a profound influence on other Greek thinkers and therefore on Western history. Some believe Anaximander was a pupil of Thales. Early sources report that one of Anaximander's more famous pupils, Pythagoras, visited Thales as a young man, and that Thales advised him to travel to Egypt to further his philosophical and mathematical studies.

Many philosophers followed Thales' lead in searching for explanations in nature rather than in the supernatural; others returned to supernatural explanations, but couched them in the language of philosophy rather than of myth or of religion.

Looking specifically at Thales' influence during the pre-Socratic era, it is clear that he stood out as one of the first thinkers who thought more in the way of logos than mythos. The difference between these two more profound ways of seeing the world is that mythos is concentrated around the stories of holy origin, while logos is concentrated around the argumentation. When the mythical man wants to explain the world the way he sees it, he explains it based on gods and powers. Mythical thought does not differentiate between things and persons and furthermore it does not differentiate between nature and culture. The way a logos thinker would present a world view is radically different from the way of the mythical thinker. In its concrete form, logos is a way of thinking not only about individualism, but also the abstract. Furthermore, it focuses on sensible and continuous argumentation. This lays the foundation of philosophy and its way of explaining the world in terms of abstract argumentation, and not in the way of gods and mythical stories.

In 2008 a group of quants in the City of London has started referring to themselves as The Thalesians as a token of their acceptance of Thales' philosophy.

Sources

Our sources on the Milesian philosophers (Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes) were either roughly contemporaneous (such as Herodotus) or lived within a few hundred years of his passing. Moreover, they were writing from a tradition that was well-known. Compared to most people, places and things of classical antiquity, we know a great deal about Thales. Most modern dissension comes from trying to interpret what we know, in particular, distinguishing legend from fact.

Diogenes Laertius lists two works, quoted above, written by Thales, and also relates the strange tradition that he did not write. Diogenes, however, had access to two of Thales' letters, which he quotes. Those writings are two more than the surviving works of Socrates, which are none. And yet, thanks to Plato, we know as much about Socrates as anyone. More than likely, the non-writing tradition about Thales is a complaint that such a famous man did not leave enough to be quoted by the secondary sources.

The main secondary source concerning the details of Thales' life and career is Diogenes Laertius (DL here), "Lives of Eminent Philosophers".[20] This is primarily a biographical work, as the name indicates. Compared to Aristotle, DL is not much of a philosopher. He is the one who, in the Prologue to that work, is responsible for the division of the early philosophers into "Ionian" and "Italian", but he places the Academics in the Ionian school and otherwise evidences considerable disarray and contradiction, especially in the long section on forerunners of the "Ionian School." DL does give us the extant primary sources on Thales (the two letters and some verses). Note, however, that DL wrote some eight centuries after Thales' death and that his sources often contained "unreliable or even fabricated information,"[21] hence the concern for separating fact from legend in accounts of Thales.

Most philosophic analyses of the philosophy of Thales come from Aristotle, an Academic and a professional philosopher, tutor of Alexander the Great. Aristotle may or may not have had access to the now mysterious possible works of Thales. Again, it is important to remember that Aristotle wrote 200 years after Thales death, and it was Aristotle's express goal to present Thales work, not because it was significant in itself, but as a prelude to Aristotle's own work.[22] Geoffrey Kirk and John Raven, English compilers of the fragments of the Pre-Socratics, assert that Aristotle's "judgments are often distorted by his view of earlier philosophy as a stumbling progress toward the truth that Aristotle himself revealed in his physical doctrines."[23] There was also an extensive oral tradition. Both the oral and the written were commonly read or known by all educated men in the region.

Academic philosophy had a distinct stamp: it professed the theory of matter and form, which modern scholastics have dubbed hylomorphism. Though once very widespread, it was not generally adopted by rationalist and modern science, as it mainly is useful in metaphysical analyses, but does not lend itself to the detail that is of interest to modern science. It is not clear that the theory of matter and form existed as early as Thales, and if it did, whether Thales espoused it.

See also

Notes

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983b18.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand. "The History of Western Philosophy." 1945

- ^ Herodotus, 1.74.2, and A. D. Godley's footnote 1; Pliny, 2.9 (12) and Bostock's footnote 2.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, 1.43, 44.

- ^ Book 1

- ^ 1.25

- ^ 1.22

- ^ English physics comes from it, but the latter is a Greek loan. In addition the quite ancient native English word be comes from the same Indo-European root.

- ^ The initial g of the archaic Latin gives the root away as *genə-, "beget."

- ^ Metaphysics 983b6

- ^ 983 b6 8-11

- ^ Lines 17-21 with gaps.

- ^ Work cited, paragraph 27.

- ^ Quaes. Hom. 22, not the same as Heraclitus of Ephesus

- ^ De natura Deorum, i.,10

- ^ Virgil:"Aeneid," vi., 724-727.)

- ^ Wisdom of the West

- ^ § 3

- ^ The Vienna Lecture

- ^ You can arrive at an online version by following the links down, but here is a link to a translation of his article on Thales: Thales, classicpersuasion site, and here is another to the original Greek text, under ΘΑΛΗΣ, the Library of Ancient Texts Online site.

- ^ see Richard MiKirahan, Philosophy Before Socrates (Hackett, 1994) 5.

- ^ See Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983b 1-27.

- ^ Kirk and Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers, Second Edition (Cambridge University Press, 1983) 3.

References

- Burnet, John (1957) [1892]. Early Greek Philosophy. The Meridian Library. (reprinted from the 4th edition, 1930; the first edition was published in 1892). An online presentation of the Third Edition can be found in the Online Books Library of the University of Pennsylvania.

- Diogenes Laertius, "Thales", in The Lives And Opinions Of Eminent Philosophers, C. D. Yonge (translator), Kessinger Publishing, LLC (June 8, 2006) ISBN 1428625852.

- Herodotus; Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920; ISBN 0674991338. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Kirk, G.S. (1957). The Presocratic Philosophers. Cambridge: University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) (subsequently reprinted) - G. E. R. Lloyd. Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle.

- Nahm, Milton C. (1962) [1934]. Selections from Early Greek Philosophy. Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc.

- Pliny the Elder; The Natural History (eds. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A.) London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. (1855). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

Further reading

- Morse, Sidney H.; Marvin, Joseph B., The Radical, A. Williams & Co., 1868. Cf. p.170 and on.

External links

- Thales of Miletus from The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Thales of Miletus from the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- Livius, Thales of Miletus by Jona Lendering

- Thales

- Thales' Theorem - Math Open Reference With interactive animation

- Thales biography by Charlene Douglass With extensive bibliography.