Peking Man

| Peking Man Temporal range: Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

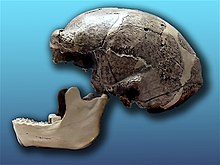

| First cranium of Homo erectus pekinensis (Sinathropus pekinensis) discovered in 1929 in Zhoukoudian, today missing (replica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | H. e. pekinensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo erectus pekinensis (Black, 1927)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Sinanthropus pekinensis | |

Peking Man (Chinese: 北京猿人; pinyin: Běijīng Yuánrén), also called Sinanthropus pekinensis (currently Homo erectus pekinensis), is an example of Homo erectus. A group of fossil specimens was discovered in 1923-27 during excavations at Zhoukoudian (Chou K'ou-tien) near Beijing (known as Peking at that time), China. More recently, the finds have been dated from roughly 500,000 years ago[1], although a new 26Al/10Be dating suggests they may be as much as 680,000-780,000 years old.[2][3]

Relation to modern people

Paleontologists see continuity in skeletal remains.[4] what may suggest that the modern humans are descendants of Peking Man. Supportive for this hipothetis may be in divergent genetic lineages in RRM2P4 gene[5][6] is deeply rooted in modern human in East Asia. The genome data with mtDNA suggest that the east Asia population may be descend from cross of lineages from East Asia and from Africa, like other humans, in accordance with the multiregional evolution.

Discovery and identification

Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson and American palaeontologist Walter W. Granger came to Zhoukoudian, China in search of prehistoric fossils in 1921. They were directed to the site at Dragon Bone Hill by local quarry men, where Andersson recognised deposits of quartz that were not native to the area. Immediately realising the importance of this find he turned to his colleague and announced, "Here is primitive man, now all we have to do is find him!"[7]

Excavation work was begun immediately by Andersson's assistant Austrian palaeontologist Otto Zdansky, who found what appeared to be a fossilised human molar. He returned to the site in 1923 and materials excavated in the two subsequent digs were sent back to Uppsala University in Sweden for analysis. In 1926 Andersson announced the discovery of two human molars found in this material and Zdansky published his findings.[8]

Canadian anatomist Davidson Black of Peking Union Medical College, excited by Andersson and Zdansky’s find, secured funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and recommenced excavations at the site in 1927 with both Western and Chinese scientists. A tooth was unearthed that fall by Swedish palaeontologist Anders Birger Bohlin which Davidson placed in a locket around his neck.

Davidson published his analysis in the journal Nature, identifying his find as belonging to a new species and genus which he named Sinanthropus pekinensis, but many fellow scientists were skeptical of such an identification based on a single tooth and the Foundation demanded more specimens before they would give an additional grant.[9]

A lower jaw, several teeth, and skull fragments were unearthed in 1928. Black presented these finds to the Foundation and was rewarded with an $80,000 grant that he used to establish the Cenozoic Research Laboratory.

Excavations at the site under the supervision of Chinese archaeologists Yang Zhongjian, Pei Wenzhong, and Jia Lanpo uncovered 200 human fossils (including 6 nearly complete skullcaps) from more than 40 individual specimens. These excavation came to an end in 1937 with the Japanese invasion.

Fossils of Peking Man were placed in the safe at the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the Peking Union Medical College. Eventually, in November 1941, secretary Hu Chengzi packed up the fossils so they could be sent to USA for safekeeping until the end of the war. They vanished en route to the port city of Qinghuangdao. They were probably in possession of a group of US marines whom the Japanese captured when the war began between Japan and the USA.

Various parties have tried to locate the fossils, but so far they have been without result. In 1972, a US financier Christopher Janus promised a $5,000 (USD) reward for the missing skulls; one woman contacted him, asking for $500,000 (USD) but she later vanished. In July 2005, the Chinese government founded a committee to find the bones to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II.

There are various theories of what might have happened, including a theory that the bones sank with the Japanese ship Awa Maru in 1945.[10]

Subsequent Research

Excavations at Zhoukoudian resumed after the war, and parts of another skull were found in 1966. To date a number of other partial fossil remains have been found. The Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1987.[11] New excavations are scheduled to start at the site in the middle of May 2009.[12]

Paleontological conclusions

The first specimens of Homo erectus had been found in Java in 1891 by Eugene Dubois, but were dismissed by many as the remains of a deformed ape. The discovery of the great quantity of finds at Zhoukoudian put this to rest and Java Man, who had initially been named Pithecanthropus erectus, was transferred to the genus Homo along with Peking Man.[13]

Contiguous findings of animal remains and evidence of fire and tool usage, as well as the manufacturing of tools, were used to support H. erectus being the first "faber" or tool-worker. The analysis of the remains of "Peking Man" led to the claim that the Zhoukoudian and Java fossils were examples of the same broad stage of human evolution.

This interpretation was challenged in 1985 by Lewis Binford, who claimed that the Peking Man was a scavenger, not a hunter. The 1998 team of Steve Weiner of the Weizmann Institute of Science concluded that they had not found evidence that the Peking Man had used fire.[citation needed]

Relation to modern Chinese people

Some Chinese paleoanthropologists have asserted in the past that the modern Chinese (and possibly other ethnic groups) are descendants of Peking Man. A recent study undertaken by Chinese geneticist Jin Li showed that the genetic diversity of modern Chinese people is well within the whole world population. This shows that there could not have been any inter-breeding between modern human immigrants to East Asia and Homo erectus, such as Peking Man, and affirms that the Chinese are descended from Africa, like all other modern humans, in accordance with the Recent single-origin hypothesis.[14][15][16]

However, another modern genetic research does support this hypothesis in RRM2P4 gene,[17][18] with the genome data affirms that the Chinese may be descend from both lineges from East Asia and from Africa, like all other humans, in accordance with the multiregional evolution. Additionaly, paleontologists see continuity in skeletal remains.[19]

Popular culture

- The disappearance of Peking Man's remains, and speculation of where they ended up, is the plot of 1975-01-07 episode Season 7, Episode 160 of Hawaii Five-O, "Bones of Contention". [1]

- Canadian science-fiction writer Robert J. Sawyer won an Aurora Award for his 1996 short story "Peking Man," which connects the lost bones to the Dracula legend; the story first appeared in the anthology Dark Destiny III: Children of Dracula edited by Edward E. Kramer, and is reprinted in Sawyer's collection Iterations.

- The discovery of Peking Man is referred to in the book The Bonesetter's Daughter by Amy Tan.

- Peking Man is part of the central plot in the mystery Sleeping Bones by Katherine V. Forrest.

- A Peking Man fossil is among those that can be found in the Nintendo DS video game Animal Crossing: Wild World as well as in the Wii video game Animal Crossing: City Folk.

- Peking Man is part of the central plot of Philip K. Dick's The Crack In Space.

- Peking Man's bones is the subject of an episode of the Japanese Anime "Lupin the 3rd" titled: Jumping the Bones

- Peking Man is part of the plot of Clive Cussler's Flood Tide

- Peking Man is the main part of the central plot of Carolyn G. Hart's mystery novel Skulduggery, set in San Francisco's Chinatown in the early 1980s. ISBN 0-7862-2672-2

- The mystery of the missing Peking Man fossils is central to the 1999 novel Lost in Translation, by Nicole Mones.

- Sega and Vivarium Inc.'s "Seaman 2 Peking Genjin no Ikusei Kit" (Peking Man Growth Kit) for the PlayStation 2 will let players interact with a 20 centimeter tall Peking Man clone.

- Peking Man is a main theme within Amir D. Aczel's The Jesuit and the Skull: Teilhard de Chardin, Evolution, and the Search for Peking Man

See also

- Zhoukoudian

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

Further reading

- Jia, Lanpo, Huang, Weiwen. The Story of Peking Man: From Archaeology to Mystery. Oxford University Press, USA, 1990.

- Sautman, B. “Peking man and the politics of paleoanthropological nationalism in China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 60, no. 1 (2001): 95-124.

- Schmalzer, Sigrid, The People's Peking Man: Popular Science and Human Identity in Twentieth-Century China. The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Wu, R., and S. Lin. “Peking Man.” Scientific American 248, no. 6 (1983): 86-94.

- Jake Hooker - The Search for the Peking Man Archaeology magazine March/April 2006)

References

- ^ Ian Tattersall. "Out of Africa again...and again?". Scientific American. 276 (4): 60–68.

- ^ Shen, G; Gao, X; Gao, B; Granger, De (2009). "Age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus determined with (26)Al/(10)Be burial dating". Nature. 458 (7235): 198–200. doi:10.1038/nature07741. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19279636.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7937351.stm

- ^ Shang; et al. (1999). "An early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, Zhoukoudian, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (16): 6573. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702169104. PMID 17416672.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ sequence. Gene tree for RRM2P4 haplotypes oxfordjournals.org

- ^ Garrigan, D; Mobasher, Z; Severson, T; Wilder, Ja; Hammer, Mf (2005). "Evidence for archaic Asian ancestry on the human X chromosome" (Free full text). Molecular biology and evolution. 22 (2): 189–92. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi013. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 15483323.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The First Knock at the Door". Peking Man Site Museum.

In the summer of 1921, Dr. J.G. Andersson and his companions discovered this richly fossiliferous deposit through the local quarry men's guide. During examination he was surprised to notice some fragments of white quartz in tabus, a mineral normally foreign in that locality. The significance of this occurrence immediately suggested itself to him and turning to his companions, he exclaimed dramatically "Here is primitive man, now all we have to do is find him!"

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The First Knock at the Door". Peking Man Site Museum.

For some weeks in this summer and a longer period in 1923 Dr. Otto Zdansky carried on excavations of this cave site. He accumulated an extensive collection of fossil material, including two Homo erectus teeth that were recognized in 1926. So, the cave home of Peking Man was opened to the world.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Morgan Lucas" (PDF).

- ^ "Sinking and salvage of the Awa Maru" (PDF).

- ^ "Unesco description of the Zhoukoudian site".

- ^ Xinhua article, 4 May 2009

- ^ Melvin, Sheila (October 11 2005). "Archaeology: Peking Man, still missing and missed". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved April 20.

The discovery also settled a controversy as to whether the bones of Java Man - found in 1891 - belonged to a human ancestor. Doubters had argued that they were the remains of a deformed ape, but the finding of so many similar fossils at Dragon Bone Hill silenced such speculation and became a central element in the modern interpretation of human evolution.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Jin; et al. (1999). "Distribution of haplotypes from a chromosome 21 region distinguishes multiple prehistoric human migrations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (7): 3796. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3796. PMID 10097117.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "multiregional or single origin".

- ^ "mapping human history p130-131".

- ^ sequence and gene tree for RRM2P4 haplotypes oxfordjournals.org

- ^ Garrigan, D; Mobasher, Z; Severson, T; Wilder, Ja; Hammer, Mf (2005). "Evidence for archaic Asian ancestry on the human X chromosome" (Free full text). Molecular biology and evolution. 22 (2): 189–92. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi013. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 15483323.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shang; et al. (1999). "An early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, Zhoukoudian, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (16): 6573. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702169104. PMID 17416672.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)