Gospel of John

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

The Gospel of John (literally, According to John; Greek, Κατὰ Ἰωάννην, Katá Iōánnēn) is the fourth gospel in the canon of the New Testament, traditionally ascribed to John the Evangelist. Like the three synoptic gospels, it contains an account of some of the actions and sayings of Jesus of Nazareth, but differs from them in ethos and theological emphases. The Gospel may have been written with an evangelistic purpose, primarily for Greek-speaking Jews who were not believers[1] or to strengthen the faith of Christians.[2] A second purpose was to counter criticisms or unorthodox beliefs of Jews, John the Baptist's followers, and those who believed Jesus was only spirit and not flesh.[3]

As a gospel, John is a story about the life of Jesus. The Gospel can be divided into four parts:

The PrologueJn. 1:1–18 is a hymn identifying Jesus as the Logos and as God. The Book of Signs 1:19–12:50 recounts Jesus' public ministry, and includes the signs worked by Jesus and some of his teachings. The Passion narrative13–20 recounts the Last Supper (focusing on Jesus' farewell discourse), Jesus' arrest and crucifixion, his burial, and resurrection. The EpilogueJohn 21 records a resurrection appearance of Jesus to the disciples in Galilee.

Of the four gospels, John presents the highest Christology, describing Jesus as the Logos who was in the Arche (a Greek term for "the beginning" or "the ultimate source of all things"),[5] teaching at length about his identity as savior, and declaring him to be God.[6]

Compared to the Synoptic Gospels, John focuses on Jesus' mission to bring the Logos ("Word", "Wisdom", "Reason" or "Rationality") to his disciples. Only in John does Jesus talk at length about himself, including a substantial amount of material Jesus shared with the disciples only. Here Jesus' public ministry consists largely of miracles not found in the Synoptics, including raising Lazarus from the dead. In John, Jesus, not his message, has become the object of veneration.[3] Certain elements of the synoptics (such as parables, exorcisms, and possibly the Second Coming) are not found in John.

Following on from "the higher criticism" of the 19th century, scholars such as Adolf von Harnack[7] and Raymond E. Brown[8] have questioned the gospel of John as a reliable source of information about the historical Jesus.[9][10]

Narrative summary (structure and content of John)

Template:Chapters in the Gospel of John

After the prologue,John 1:1–5 the narrative of the gospel begins with verse 6, and consists of two parts. The first part1:6–12:50 relates Jesus' public ministry from John the Baptist recognizing him as the Lamb of God to the raising of Lazarus and Jesus' final public teaching. In this first part, John emphasizes seven of Jesus' miracles, always calling them "signs." The second part13–21 presents Jesus in dialogue with his immediate followers13–17 and gives an account of his Passion and Crucifixion and of his appearances to the disciples after his Resurrection.18–20 In the "appendix",21 Jesus restores Peter after his denial, predicts Peter's death, and discusses the death of the "beloved disciple".

Raymond E. Brown, a scholar of the social environment where the Gospel and Letters of John emerged, labelled the first and second parts the "Book of Signs" and the "Book of Glory", respectively.[11]

Hymn to the Word

This prologue is intended to identify Jesus as the eternal Word (Logos) of God.[2] Thus John asserts Jesus' innate superiority over all divine messengers, whether angels or prophets.[3] Here John adapts the doctrine of the Logos, God's creative principle, from Philo, a 1st-century Hellenized Jew.[3]

Philo had adopted the term Logos from Greek philosophy, using it in place of the Hebrew concept of Wisdom (sophia) as the intermediary (angel) between the transcendent Creator and the material world.[3] Some scholars argue that the prologue was taken over from an existing hymn and added at a later stage in the gospel's composition.[2]

Seven Signs

This section recounts Jesus' public ministry.[2] It consists of seven miracles or "signs," interspersed with long dialogues and discourses, including several "I am" sayings.[3] The miracles culminate with his most potent, raising Lazarus from the dead.[3] In John, it is this last miracle, and not the temple incident, that prompts the authorities to have Jesus executed.[3] Jesus' discourses identify him with symbols of major significance, "the bread of life,"6:35 "the light of the world,"8:12 "the door of the sheep",10:7 "the good shepherd," 10:11 "the resurrection and the life," 11:25 "the way, the truth, and the life," 14:6 and "the real vine."15:1[3] Critical scholars think that these claims represent the Christian community's faith in Jesus' divine authority but doubt that the historical Jesus actually made these sweeping claims.[3] The teachings of Jesus are so different in John from those found in the synoptic gospels, that since the 1800s some scholars have believed that only one of the two traditions could be authentic, and these have unanimously chosen the synoptics as the source for the teachings of historical Jesus.[12]

Last teachings and death

This section opens with an account of the Last Supper that differs significantly from that found in the synoptics.[3] Here, Jesus washes the disciples feet instead of ushering in a new covenant of his body and blood.[3] John then devotes almost five chapters to farewell discourses.[3] He declares his unity with the Father, promises to send the Paraclete, describes himself as the "real vine," explains that he must leave (die) before the Holy Spirit comes, and prays that his followers be one.[3] The farewell discourses resemble farewell speeches called testaments, in which a father or religious leader, often on the deathbed, leaves instructions for his children or followers.[13] Verses 14:30-31 represent a conclusion, and most modern scholars regard the next three chapters to have been inserted later.[13] Most scholars regard the discourses as having been assembled over time, representing the theology of the "Johannine circle" more than the message of the historical Jesus.[13]

John then records Jesus' arrest, trial, execution, and resurrection appearances, including "doubting Thomas."[3] Significantly, John does not have Jesus claim to be the Son of God or the Messiah before the Sanhedrin or Pilate, and he omits the traditional earthquakes, thunder, and midday darkness that were said to accompany Jesus' death.[3] John's revelation of divinity is Jesus' triumph over death, the eighth and greatest sign.[3]

Chapter 21, in which the "beloved disciple" claims authorship, is commonly assumed to be an appendix, probably added to allay concerns after the death of the beloved disciple.[3] There had been a rumor that the End would come before the beloved disciple died.[14]

Detailed contents

The major events covered by the Gospel of John include:

Authorship and date

Authorship

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Related literature |

| See also |

John the Apostle, a disciple of Jesus, has been generally accepted as the author of the Fourth Gospel until the modern era. The authorship of the Fourth Gospel was rarely questioned seriously until the end of the eighteenth century.[15] The vast majority of modern scholars posit that the author was not an eyewitness to Jesus' ministry.[16] Some contemporary scholars suggest still other possibilities of authorship.

John the Evangelist

The Fourth Gospel, like the three Synoptic Gospels, is anonymous in that it does not bear its author's name. The title, "According to John," was attached when the four Gospels were gathered together and began to circulate as one collection.[17]

The tradition that an apostle of Jesus wrote the Gospel can be found in the first two decades of the second century. There are some Church Fathers in the remainder of the second century that ascribe the text to John the Apostle.[18] Attestation of Johannine authorship is evidenced as early as Irenaeus.[2] Eusebius wrote that Irenaeus received his information from Polycarp, who is said to have known the apostles.

John A. T. Robinson, a staunch defender of the apostolic authorship of the Gospel, says the Johannine tradition did not suddenly emerge about AD 100. He says there is "a real continuity, not merely in the memory of one old man, but in the life of an ongoing community, with the earliest days of Christianity."[19]

The text itself is unclear about the issue. John 21:20–25 contains information that could be construed as autobiographical. Conservative scholars generally assume that first person "I" in verse 25, the disciple in verse 24 and the disciple whom Jesus loved (also known as the Beloved Disciple) in verse 20 are the same person.[20] Critics point out that the abrupt shift from third person to first person in vss. 24–25 indicates that the author of the epilogue, who is supposedly a third-party editor, claims the preceding narrative is based on the Beloved Disciple's testimony, while he himself is not the Beloved Disciple.[21][22] An early document from circa 170, the Muratorian fragment, states that while John was the primary author, several people were involved; that mutual revision was part of the original intent of the authors; and that the editors included the apostle Andrew.

The Alogi, a 2nd-century sect that denied the doctrine of the Logos, ascribed this gospel, as well as the Book of Revelation, to the Gnostic Cerinthus.[23] Irenaeus, on the other hand, asserted that John wrote his gospel to refute Cerinthus.[24]

Contemporary scholarship

Starting in the 19th century, critical scholarship has further questioned the apostle John's authorship, regarding the author as anonymous.[3]: 302 [25][26] They most often date it to c 90–100, decades after the events it describes.[3] Bart Ehrman argues that there are differences in the composition of the Greek within the Gospel, such as breaks and inconsistencies in sequence, repetitions in the discourse, as well as passages that clearly do not belong to their context, and these suggest redaction.[27]

Raymond E. Brown summarizes a prevalent theory regarding the development of this gospel.[8]: 363–364 He identifies three layers of text in the Fourth Gospel (a situation that is paralleled by the synoptic gospels):

- An initial version Brown considers based on personal experience of Jesus;

- A structured literary creation by the evangelist which draws upon additional sources;

- The edited version that readers know today.

Still different theories of authorship have been advanced by other notable theologians. Chapman University scholar of religion contends the author of John’s Gospel was Mary Magdalene.[28]

Among scholars, Ephesus in Asia Minor is a popular suggestion for the gospel's origin.[3]

Date

There is no certain historical evidence as to the date of its composition. The so-called "Monarchian Prologue" to the Fourth Gospel (c. 200) supports A.D. 96 or one of the years immediately following as to the time of its writing.[29] Most scholars agree on a range of c. 90–100.[30] Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church says it was already in existence early in the 2nd Century.[31]: p.313

Conservative scholars consider internal evidences, such as the lack of the mention of the destruction of the Temple and a number of passages that they consider characteristic of an eyewitness,[32] sufficient evidence that the gospel was composed before 100 and perhaps as early as 50–70. Barrett suggests an earliest date of 90, based on familiarity with Mark’s gospel, and the late date of a synagogue expulsion of Christians (which is a theme in John).[33] Morris suggests 70, given Qumran parallels and John’s turns of phrase, such as "his disciples" vs. "the disciples".[34] John A.T. Robinson proposes an initial edition by 50–55 and then a final edition by 65 due to narrative similarities with Paul.[35]: 284, 307 Other critical scholars also are of the opinion that John was composed in stages (probably two or three).[36]: p.43

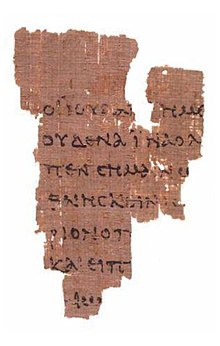

While most scholarly evidence points to first century authorship, there is credible evidence that the Gospel was written no later than the middle of the second century. Since the middle of the second century writings of Justin Martyr use language very similar to that found in the gospel of John, the Gospel is considered to have been in existence at least at that time.[37] The Rylands Library Papyrus P52, which records a fragment of this gospel, is usually dated to the first half of the second century.[38]

The non-canonical Dead Sea Scrolls suggest an early Jewish origin, parallels and similarities to the Essenne Scroll, and Rule of the Community.[39] Many phrases are duplicated in the Gospel of John and the Dead Sea Scrolls. These are sufficiently numerous to challenge the theory that the Gospel of John was the last to be written among the four Gospels[40] and that it shows marked Greek influence.[41]

The traditional view is supported by reference to the statement of Clement of Alexandria that John wrote to supplement the accounts found in the other gospels.[42] This would place the writing of John's gospel sufficiently after the writing of the synoptics. However, there are modern scholars that now view the Gospel of John as thoroughly Jewish and his Gospel perhaps the earliest of the four.[41]

Textual history and manuscripts

Perhaps the earliest surviving manuscript of the New Testament is Rylands Library Papyrus P52, discovered in Egypt in 1920 (now at the John Rylands Library, Manchester). Although P52 is a Greek papyrus fragment, with no more than 112 legible letters, it must come from a substantial codex book; as it is written on both sides, with John 18:31–33 on one side and John 18:37–38on the other. Most reference books list the probable date for this manuscript as c. 125.[43][44]; but the difficulty of estimating the date of a literary text based solely on paleographic evidence must allow potentially for a range that extends from before 100 to well into the second half of the second century. P52 is small, and although a plausible reconstruction can be attempted for most of the fourteen lines represented, nevertheless the proportion of the text of the Gospel of John for which it provides a direct witness is necessarily limited, so it is rarely cited in textual debate.[45] Other notable early manuscripts include Papyrus 66 and Papyrus 75, in consequence of which a substantially complete text of the Gospel of John exists from the beginning of the 3rd century at the latest.

Much current research on the textual history of the Gospel of John is being done by the International Greek New Testament Project.

Source criticism

Source criticism is the practice of deducing an author's or redactor's sources, especially in Biblical criticism.

Signs gospel

In 1941 Rudolf Bultmann suggested[46] that the author of John depended in part on an oral miracles tradition or manuscript account of Christ's miracles that was independent of, and not used by, the synoptic gospels. This hypothetical "Signs Gospel" is alleged to have been circulating before 70. Its traces can be seen in the remnants of a numbering system associated with some of the miracles that appear in the Gospel of John: all of the miracles that are mentioned only by John occur in the presence of John[citation needed]; the "signs" or semeia (the expression is uniquely John's) are unusually dramatic; and they are accomplished in order to call forth faith (see John 12:37). These miracles are different both from the rest of the "signs" in John, and from the miracles in the synoptic gospels, which occur as a result of faith. Bultmann's conclusion that John was reinterpreting an early Hellenistic tradition of Jesus as a wonder-worker, a "magician" within the Hellenistic world-view, was so controversial that heresy proceedings were instituted against him and his writings. (See: Images of Jesus and more detailed discussions linked below.)

Egerton gospel

The mysterious Egerton Gospel appears to represent a parallel but independent tradition to the Gospel of John. According to scholar Ronald Cameron, it was originally composed some time between the middle of the first century and early in the second century, and it was probably written shortly before the Gospel of John.[47] Robert W. Funk, et al., places the Egerton fragments in the 2nd century, perhaps as early as 125, which would make it as old as the oldest fragments of John.[48]

Characteristics of the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John is easily distinguished from the three Synoptic Gospels, which share a considerable amount of text. Over 90% of the Gospel is unique to John.[49] The synoptics describe much more of Jesus' life, miracles, parables, and exorcisms. However, the materials unique to John are notable, especially in their effect on modern Christianity.

Christology

John portrays Jesus Christ as "a brief manifestation of the eternal Word, whose immortal spirit remains ever-present with the believing Christian."[3]: 304 The book presents Jesus as divine and yet subordinate to the one true God.[50] The gospel gives far more focus to the relationship of the Son to the Father than the other gospels and it has often been used in the Christian development and understanding of the Trinity. John includes far more direct claims of Jesus being the only Son of God than the Synoptic Gospels. The gospel also focuses on the relation of the Redeemer to believers, the announcement of the Holy Spirit as the Comforter (Greek Paraclete), and the prominence of love as an element in the Christian character.

Jesus' divine role

In the synoptics, Jesus speaks mostly about the Kingdom of God. His own divine role is obscured (see Messianic secret). In John, Jesus talks openly about his divine role. He says, for example, that he is the way, the truth, and the life. He echoes Yahweh's own statements with several "I am" declarations.[3]: 302–310

John also promises eternal life for those who believe in Jesus.

Logos

Christians have translated the opening verse of John as "the Word was with God and the Word was God" in all orthodox and historical Bibles.[51]

Historical Criticism scholars like Bart Ehrman[52][53] and religious groups like the Jehovah's Witnesses have attempted to prove that John meant "a god" with an analysis of the optional Greek article "hos" which is present on "theos"[54] and then is missing from the subsequent "theos".[14]

John the Baptist

John's account of the Baptist is different from that of the synoptic gospels. John is not called "the Baptist",[2] though stress is laid on his being sent to baptize with water.[citation needed] John's ministry overlaps with Jesus', his baptism of Jesus is not explicitly mentioned, but his witness to Jesus is unambiguous.[2] The evangelist almost certainly knew the story of John's baptism of Jesus and he makes a vital theological use of it.[55] He subordinates John to Jesus, perhaps in response to members of the Baptist's sect who denied Jesus' superiority.[3]

In John, Jesus and his disciples go to Judea early in Jesus' ministry when John has not yet been imprisoned and executed by Herod. He leads a ministry of baptism larger than John's own. The Jesus Seminar rated this account as black, containing no historically accurate information.[56] Historically, John likely had a larger presence in the public mind than Jesus.[57]

Jews

The Gospel’s treatment of the role of the Jewish authorities in the Crucifixion has given rise to allegations of anti-Semitism. The Gospel often employs the title "the Jews" when discussing the opponents of Jesus. The meaning of this usage has been the subject of debate, though critics of the “anti-Semitic” theory cite that the author most likely considered himself Jewish and was probably speaking to a largely Jewish community.

Gnostic elements

Christian Gnosticism did not fully develop until sometime around the mid-second century CE. As Roger Olson noted, “second-century Christian leaders and thinkers expended tremendous energies examining and refuting it.”[58] To say John’s Gospel contained elements of Gnosticism is to assume that Gnosticism had developed to a level that required the author respond to it. Nevertheless, it should be noted that comparisons to Gnosticism are based, fairly or unfairly, not in what the author says, but in the language s/he uses to say it; notably, use of the concepts of Logos and Light.

However, to say the author was Proto-Gnostic, or even Docetic, would be a misinterpretation of the prologue contained in the first eighteen verses of the text. As noted by Gordon Fee, the proper exegete of any text begins with a survey of the historical context of entire document.[59]: 34 Therefore, we must ask who was the author’s intended audience? Raymond E. Brown noted, "John is most often characterized as a Hellenistic Gospel."[8]: 371 This is to say the author of John’s Gospel addressed people familiar with Greek thought and philosophy. When the author identified Christ as the Logos (Gk. word), Greek-speaking Jews and Gentiles heard a philosophically charged word that evoked images of Platonic dualism. However, as the author noted, the “Logos” became “Sarkos” (Gk. flesh or carnal) and was the true light which illuminates every person and overcomes all darkness. Theologically, this is inconsistent with classical Greek dualism and a repudiation of any form of Gnosticism and Docetism as well which held that Christ was not flesh but spirit.

Though not commonly understood as Gnostic, John has elements in common with Gnosticism.[3] Gnostics must have read John because it is found with Gnostic texts.[citation needed] The root of Gnosticism is that salvation comes from gnosis, secret knowledge. The nearly five chapters of the "farewell discourses" (John 13, 18) Jesus shares only with the Twelve Apostles. Jesus pre-exists birth as the Word (Logos). This origin and action resemble a gnostic aeon (emanation from God) being sent from the pleroma (region of light) to give humans the knowledge they need to ascend to the pleroma themselves.[citation needed] John's denigration of the flesh, as opposed to the spirit, is a classic Gnostic theme.

Raymond Brown contends that "The Johannine picture of a savior who came from an alien world above, who said that neither he nor those who accepted him were of this world (17:14), and who promised to return to take them to a heavenly dwelling (14:2-3) could be fitted into the gnostic world picture (even if God's love for the world in 3:16 could not)."[8]: 375

It has been suggested that similarities between John's Gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish Apocalyptic literature.Kovacs, Judith L. (1995).[60]

Thomas

In John, the apostle Thomas appears at one point as brave (John 11:16), at another as "doubting Thomas" (John 20:25). He doubts that Jesus has risen physically from the grave, and Jesus proves that he has. While the tradition of John was popular in Asia Minor, the tradition of Thomas was popular in neighboring Syria. To him was attributed a version of Jesus' teachings with Gnostic elements, which appears in the Gospel of Thomas. In John, the author uses Thomas himself to demonstrate that Jesus rose in the flesh.

Historical reliability of John

Since the advent of critical scholarship, John's historical importance has generally been considered less significant than the synoptic gospels. The scholars of the 19th century concluded that the Gospel of John had little historical value. Today, prominent historians, such as E. P. Sanders, look mainly to Mark, Matthew, and Luke for historical information about Jesus.[12] Some scholars today believe that parts of John represent an independent historical tradition from the synoptics, while other parts represent later traditions.[61] The Gospel was probably shaped in part by increasing tensions between synagogue and church, or between those who believed Jesus was the Messiah and those who did not.[62] The scholars of the Jesus Seminar assert that there is little historical value in John and consider nearly every Johannine saying of Jesus to be nonhistorical.[63] J. D. G. Dunn comments: "few scholars would regard John as a source for information regarding Jesus' life and ministry in any degree comparable to the Synoptics". [64]

Still, the gospel does contain some independent, historically plausible elements.[65] Henry Wansbrough says: "Gone are the days when it was scholarly orthodoxy to maintain that John was the least reliable of the gospels historically." It has become generally accepted that certain sayings in John are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, that John's knowledge of things around Jerusalem is often superior to the synoptics, and that his presentation of Jesus' agony in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically accurate than their synoptic parallels.[66] And Marianne Meye Thompson writes: "There are items only in John that are likely to be historical and ought to be given due weight. Jesus' first disciples may once have been followers of the Baptist (cf. John 1:35-42). There is no a priori reason to reject the report of Jesus and his disciples' conducting a ministry of baptism for a time (3:22-26). That Jesus regularly visited Jerusalem, rather than merely at the time of his death, is often accepted as more realistic for a pious, first-century Jewish male[citation needed] (and is hinted at in the other Gospels as well: Mark 11:2; Luke 13"34' 22:8-13,53)[citation needed] ... Even John's placement of the Last Supper before Passover has struck some as likely."[67]

John and the Synoptics compared

It has been suggested that Omissions in the Gospel of John be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2008. |

John is significantly different from the Synoptic Gospels in many ways. Some of the differences are:

- The Gospel of John contains four visits by Jesus to Jerusalem, three of which associated with the Passover feast. This chronology suggests Jesus' public ministry lasted three or two years. The synoptic gospels describe only one trip to Jerusalem in time for the Passover observance.

- The Kingdom of God is only mentioned twice in John.[68] In contrast, the other gospels repeatedly use the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven as important concepts.

- John does not contain any parables, that is stories each illustrating a single message or idea.[69] Rather it contains metaphoric stories or allegories, such as The Shepherd and The Vine, in which each individual element corresponds to a specific group or thing.

- The exorcisms of demons are never mentioned as in the Synoptics.[68]

- Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including the Sermon on the Mount and the Olivet discourse.

- Jesus and the Money Changers appears near the beginning of the work; in the Synoptics this occurs late in Jesus' ministry.

- Most of the action in John takes place in Judea and Jerusalem; only a few events occur in Galilee, and of those, only the feeding of the multitude and the trip across the Sea of Galilee are also found in the Synoptics.

- The crucifixion of Jesus is recorded as Nisan 14 in contrast to the synoptic Nisan 15.

- The earthquake and the Crucifixion eclipse, mentioned in Matthew, are absent.

- Jesus does not utter eschatological prophecies.

- The gospel of John makes no mention of Jesus' baptism, but quotes John the Baptist's description of the descent of the Holy Spirit an unspecified amount of time after the event.

- Thomas the Apostle is given a personality beyond a mere name, as "Doubting Thomas".

- When the water at the Pool of Bethesda is moved by an angel it heals.

- Jesus washes the disciples' feet.

- There is a description of the Last Supper but, unlike the Synoptic Gospels there is no formal institution of the Eucharist, whereas the prediction of Judas' betrayal is amply reported.

- No other women are mentioned going to the tomb with Mary Magdalene.

- When speaking, Jesus says "verily" twice, rather than just once as in the Synoptic Gospels.

- Jesus carried his own cross; in the synoptics the cross was carried by Simon of Cyrene.

History

John was written somewhere near the end of the first century, probably in Ephesus, in Anatolia. The tradition of John the Apostle was strong in Anatolia, and Polycarp of Smyrna reportedly knew him. Like the previous gospels, it circulated separately until Irenaeus proclaimed all four gospels to be scripture.[70]

In the early church, John's reference to Jesus as the eternal Logos was a popular definition of Jesus, defeating the rival view that Jesus had been born a man but had been adopted as God's Son. The gospel's description of Jesus' divinity was fundamental to the developing doctrine of the Trinity.

In the second century, Montanus of Phrygia launched a movement in which he claimed to be the Paraclete promised in John.

Jerome translated John into its official Latin form, replacing various older translations.

Although very much in line with many accounts in the Synoptic Gospels and probably primitive (the Didascalia Apostolorum definitely refers to it and it was probably known to Papias), the Pericope Adulterae is not part of the original text of the Gospel of John.[71] The evidence for this view does not convince all scholars.[72]

When Bible criticism developed in the 19th century, John came under increasing criticism as less historically reliable than the synoptics.

See also

- Textual variants in the Gospel of John

- List of Gospels

- Last Gospel

- Egerton Gospel

- John 3:16

- Jesus and the woman taken in adultery

- Gospel of Mark

- The Gospel of John (film)

- Images of Jesus

- Signs gospel

- That They All May Be One

- Free Grace theology

- List of omitted Bible verses

References

- ^ Colin G. Kruse, The Gospel According to John: An Introduction and Commentary, Eerdmans (2004), page 21. ISBN 0802827713

- ^ a b c d e f g "Gospel of John." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 Cite error: The named reference "ODCC self" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ C. Marvin Pate, et al. "The Story of Israel: a biblical theology" (InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove, 2004), 153.

- ^ Not John, but Colossians 1:18 calls Jesus himself the Arche

- ^ A detailed technical discussion can be found in Raymond E. Brown, "Does the New Testament call Jesus God?" Theological Studies 26 (1965): 545–73

- ^ "In particular, the fourth Gospel, which does not emanate or profess to emanate from the apostle John, cannot be taken as an historical authority in the ordinary meaning of the word. The author of it acted with sovereign freedom, transposed events and put them in a strange light, drew up the discourses himself, and illustrated 22 great thoughts by imaginary situations. Although, his work is not altogether devoid of a real, if scarcely recognizable, traditional element, it can hardly make any claim to be considered an authority for Jesus’ history; only little of what he says can be accepted, and that little with caution. On the other hand, it is an authority of the first rank for answering the question, What vivid views of Jesus’ person, what kind of light and warmth, did the Gospel disengage?" Adolf von Harnack What is Christianity? Lectures Delivered in the University of Berlin during the Winter-Term 1899-1900

- ^ a b c d Brown, Raymond E. (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- ^ Gospel of Saint John, in Catholic Encyclopedia 1910

- ^ Harris says John's biography is "highly problematical to scholars..." p. 268. Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Studies in John

- ^ a b Sanders, E. P. The historical figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993.

- ^ a b c Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993.

- ^ a b May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ^ Fonck, Leopold. "Gospel of St. John." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 9 Jun. 2009 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08438a.htm>.

- ^

Brown, Raymond Edward (1978). Mary in the New Testament. New York: Paulist Press. p. 198. ISBN 0809121689.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bruce, F. F. The Gospel of John Introduction, Exposition and Notes. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994. ISBN 0802808832

- ^ Hill, Charles E. (2004). The Johannine Corpus in the Early Church. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 473. ISBN 9780199291441.

- ^ Robinson, John A. T. Twelve New Testament Studies. Fortress Press, 1984. ISBN 0334016924

- ^ A Historical Introduction to the New Testament

- ^ The Gospel of John

- ^ Gospel of John

- ^ "Alogi." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Cerinthus." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Delbert Burkett, An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity, Cambridge University Press, (2002), page 215.

- ^ F. F. Bruce, The Gospel of John, Eerdmans (1994), page 1.

- ^ Ehrman 2004, p. 164–5

- ^ Meyer, Marvin and Esther De Boer. The Gospels of Mary: The Secret Tradition of Mary Magdalene, the Companion of Jesus." HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 9780060834517

- ^ Fonck, Leopold. "Gospel of St. John." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 7 Aug. 2009 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08438a.htm>.

- ^ Bruce, F.F. The New Testament Documents: Are they Reliable?.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Pages=ignored (|pages=suggested) (help) - ^ Livingstone, E. A. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press, USA, 2006.ISBN 019861442X / 978-0198614425

- ^ John 13:23ff, John 18:10, John 18:15, John 19:26–27, John 19:34, John 20:8, John 20:24–29

- ^ Barrett, C. K. The Gospel According to St. John., p.127–128

- ^ Morris, L. The Gospel According to John p.59

- ^ Robinson, John A.T. (1977). Redating the New Testament. SCM Press. ISBN 978-0334023005.

- ^ Mark Allan Powell. Jesus as a figure in history. Westminster John Knox Press, 1998. ISBN 0664257038 / 978-0664257033

- ^ Justin Martyr NTCanon.org. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Nongbri, Brent, 2005. "The Use and Abuse of P52: Papyrological Pitfalls in the Dating of the Fourth Gospel." Harvard Theological Review 98:23–52.

- ^ Rule of the Community "And by His knowledge, everything has been brought into being. And everything that is, He established by His purpose; and apart from Him nothing is done."

- ^ Roberts, “An Unpublished Fragment of the Fourth Gospel in the John Rylands Library”, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library XX, 1936:45-55.

- ^ a b [1] Out of the Desert

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History, 6.14.7.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger. The text of the New Testament: its transmission, corruption, and restoration. Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-507297-9. p.56

- ^ Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland. The Text of the New Testament: an Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1995. ISBN 0802840981 / 978-0802840981. p.99

- ^ Tuckett, p. 544; http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/ManuscriptsPapyri.html#P52; http://www.historian.net/P52.html.

- ^ Das Evangelium des Johannes, 1941 (translated as The Gospel of John: A Commentary, 1971)

- ^ Ronald Cameron, editor. The Other Gospels: Non-Canonical Gospel Texts, 1982

- ^ Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993. page 543.

- ^ Marshall, Celia Brewer and Celia B. Sinclair. A Guide Through the New Testament. Westminster John Knox Press, 1994. ISBN 0664254845

- ^ Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). How on earth did Jesus become a god?: historical questions about earliest devotion to Jesus. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. p. 53. ISBN 0802828612.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ New International Version (and Today's New International Version), New American Standard Bible, Amplified Bible, New Living Translation, King James Version, Young's Literal Translation, Darby Translation, and Wycliffe New Testament, to name a few.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D.. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4; See also Raymond E. Brown's Commentary on the Gospel of John.

- ^ The Logos "was what God was" in the Scholar's Version, meant to convey the original rather than literal meaning of the Gospels. Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "John" p. 365-440

- ^ Daniel Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Zondervan, 1996)

- ^ Barrett, C. K. The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text. Westminster John Knox Press, 1978. p. 16

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "John" p. 365-440

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "John the Baptist" cameo, p. 268

- ^ Roger E. Olson, The Story of Christian Theology, p. 36; InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL, 1999

- ^ Fee, Gordon D. (1993). New Testament Exegesis, Revised Edition. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press,.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus’ Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20–36. Journal of Biblical Literature 114(2), 227–247.

- ^ Brown (1997). "Introduction to the New Testament". (New York: Anchor Bible, 1997) p. 362–364

- ^ Thompson, Marianne Maye (2006). "The Gospel according to John". In Stephen C. Barton (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780521807661.

- ^ http://www.religioustolerance.org/chr_jsem.htm Jesus Seminar

- ^ James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered, Eerdmans (2003), page 165

- ^ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition)

- ^ Henry Wansbrough, The Four Gospels in Synopsis, The Oxford Bible Commentary, pp. 1012-1013, Oxford University Press 2001 ISBN 0198755007

- ^ Culpepper, R. Alan, and Black, C. Clifton, eds. Exploring the Gospel of John. Westminster John Knox Press, 1996. p. 28

- ^ a b Thompson, Marianne Maye (2006). "The Gospel according to John". In Stephen C. Barton (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780521807661.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Parables". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.11.8 "For, since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the Church is scattered throughout all the world, and the pillar and ground 1 Timothy 3:15 of the Church is the Gospel and the spirit of life; it is fitting that she should have four pillars, breathing out immortality on every side, and vivifying men afresh."

- ^ Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "If it is not an original part of the Fourth Gospel, its writer would have to be viewed as a skilled Johannine imitator, and its placement in this context as the shrewdest piece of interpolation in literary history!" The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text with Apparatus: Second Edition, by Zane C. Hodges (Editor), Arthur L. Farstad (Editor) Publisher: Thomas Nelson; ISBN 0840749635

Further reading

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John Anchor Bible, 1966, 1970

- Raymond E. Brown, The Community of the Beloved Disciple Paulist Press, 1979

- Robin M. Jensen, The Two Faces of Jesus, Bible Review October 2002, p42

- J.H. Bernard & A.H. McNeile, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary On The Gospel According To St. John. Edinburgh, T. & T. Clark, 1953.

- Robert Murray M'Cheyne Bethany – Discovering Christ's Love in Times of Suffering When Heaven Seems Silent, (a study of John 12) Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1846857027

External links

Online translations of the Gospel of John:

- Bible Gateway 35 languages/50 versions at GospelCom.net

- Unbound Bible 100+ languages/versions at Biola University

- Online Bible at gospelhall.org

- Text of the Gospel with textual variants

- The Egerton Gospel: text. Compare it with Gospel of John

Related articles:

- A textual commentary on the Gospel of John Detailed textcritical discussion of the 300 most important variants of the Greek text (PDF, 376 pages)

- "Signs Gospel". a hypothetical written source for miracles in the Gospel of John: discussion

- Papyrus fragment of John at the John Rylands Library; illustrated.

- John Rylands papyrus: text, translation, illustration and a bibliography of the discussion

- John, Gospel of St. in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Gospel of John – collected comments

- Conflicts Between the Gospel of John & the Remaining Three (Synoptic) Gospels on ReligiousTolerance.com.