Catch and release

Catch and release is a practice within recreational fishing intended as a technique of conservation. After capture, the fish are unhooked and returned to the water before experiencing serious exhaustion or injury. Using barbless hooks, it is often possible to release the fish without removing it from the water (a slack line is frequently sufficient).

History of practice

In the United Kingdom, catch and release has been performed for more than a century by coarse fishermen in order to prevent target species from disappearing in heavily fished waters. Since the latter part of the 20th century, many salmon and sea trout rivers have been converted to complete or partial catch and release.

In the United States, catch and release was first introduced as a management tool in the state of Michigan in 1952 as an effort to reduce the cost of stocking hatchery-raised trout. Anglers fishing for fun rather than for food accepted the idea of releasing the fish while fishing in so-called "no-kill" zones. Conservationists have advocated catch and release as a way to ensure sustainability and to avoid overfishing of fish stocks. Lee Wulff also promoted catch and release as he observed the Atlantic Salmon population dwindle.

In Australia, catch and release caught on slowly, with some pioneers practicing it the 1960s, and the practice slowly becoming more widespread in the 1970s and 1980s. Catch and release is now widely used to conserve — and indeed is critical in conserving — vulnerable fish species like the large, long lived native freshwater Murray Cod and the prized, slowly growing, heavily fished Australian bass, heavily fished coastal species like Dusky Flathead and prized gamefish like striped marlin.

In the Republic of Ireland, catch and release has been used as a conservation tool for atlantic salmon and sea trout fisheries since 2003. A number of fisheries now have mandatory catch and release regulations.[1] Catch and release for coarse fish has been used by sport anglers for as long as these species have been fished for on this island. However catch and release for Atlantic salmon has required a huge turn about in how many anglers viewed the salmon angling resource. To encourage anglers to practice catch and release in all fisheries a number of Government led incentives have been implemented.[2]

In Canada, catch and release is mandatory for some species. Canada also requires, in some cases, the use of barbless hooks to facilitate release and minimize injury.

In Switzerland, catch and release fishing is considered inhumane and is now banned.[3]

Catch and release techniques

Effective catch and release fishing techniques avoid excessive fish fighting and handling times, avoid damage to fish skin, scale and slime layers by nets, dry hands and dry surfaces (that leave fish vulnerable to fungal skin infections), and avoid damage to throat ligaments and gills by poor handling techniques.

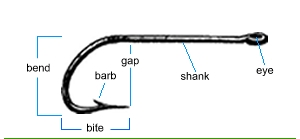

The use of barbless hooks is an important aspect of catch and release; barbless hooks reduce injury and handling time, increasing survival. Frequently, fish caught on barbless hooks can be released without being removed from the water, and the hook(s) effortlessly slipped out with a single flick of the pliers or leader. Barbless hooks can be purchased from several major manufacturers or can be created from a standard hook by crushing the barb(s) flat with needle-nosed pliers. Some anglers avoid barbless hooks because of the erroneous belief that too many fish will escape. Concentrating on keeping the line tight at all times while fighting fish, equipping lures that do not have them with split rings, and using recurved point or "Triple Grip" style hooks on lures, will keep catch rates with barbless hooks as high as those achieved with barbed hooks.

One study looking at brook trout found that barbless hooks did not result in statistically significantly lower mortality rates than barbed hooks when fish were hooked in the mouth, but did elevate mortalities if fish were hooked deeper.[4] The study also suggested bait fishing does not have a significantly higher mortality when utilized in an active style, rather than a passive manner that allows the fish to swallow the bait.[4]

To make a hook barbless, the barb is simply crushed flat with a pair of needle-nosed pliers; a 2-second task. Medium grit sandpaper can be further used to ensure complete removal of the barb, but this is not necessary and is rarely done.

The effects of catch and release vary from species to species. A study of fish caught in shallow water on the Great Barrier Reef showed high survival rates (97%+) (e.g.[5]) for released fish if handled correctly and particularly if caught on artificial baits such as lures. Fish caught on lures are usually hooked cleanly in the mouth, minimizing injury and aiding release. Other studies have shown somewhat lower survival rates for fish gut-hooked on bait if the line is cut and the fish is released without trying to remove the hook.[citation needed]

Debate

Catch and release is a conservation practice developed to prevent overharvest of fish stocks in the face of growing human populations, mounting fishing pressure, increasingly effective fishing tackle and techniques, inadequate fishing regulations and enforcement, and habitat degradation. Fishermen have been practicing catch and release for decades, including with some highly pressured fish species. Proponents of catch and release dispute the suggestion that fish hooked in the mouth feel pain.[citation needed]

Opponents of catch and release point out that fish are highly evolved vertebrates that share many of the same neurological structures that, in humans, are associated with pain perception. They point to studies that show that, neurologically, fish are quite similar to "higher" vertebrates and that blood chemistry reveals that hormones and blood metabolites associated with stress are quite high in fish struggling against hook and line. The idea that fish do not feel pain in their mouths has been studied at the University of Edinburgh and the Roslin Institute by injecting bee venom and acetic acid into the lips of rainbow trout; the fish responded by rubbing their lips along the sides and floors of their tanks in an effort to relieve themselves of the sensation.[6] Lead researcher Dr. Lynne Sneddon wrote, "Our research demonstrates nociception and suggests that noxious stimulation in the rainbow trout has adverse behavioral and physiological effects. This fulfills the criteria for animal pain." The research does not explain why popular gamefish such as largemouth bass would intentionally prey on spiny fish and crustaceans, that regularly cause hook-like puncture wounds to the inside of their mouths.

James D. Rose, Ph.D. of the University of Wyoming is among those who argue this may demonstrate a chemical sensitivity rather than pain and that the evidence for pain sensation in fish is at best ambiguous.[7][8]

Deep sea fishing and catch and release

While a number of scientific studies have now found survival rates of shallow water fish caught-and-released on fly and lure have extremely high survival rates (95–97%) and modestly high survival rates on bait (70–90%, depending on species, bait, hook size, etc.) emerging research suggests catch and release does not work very well with fish caught when deep sea fishing. New research indicates that bait mortality is more closely related to technique than to the fact that one is fishing bait, and that bait mortality is much lower than once thought.[4]

Most deep sea fish species suffer from the sudden pressure change when wound to the surface from great depths; these species cannot adjust their body's physiology quickly enough to follow the pressure change. The result is called "barotrauma". Fish with barotrauma will have their enormously swollen swim-bladder protruding from their mouth, bulging eyeballs, and often sustain other, more subtle but still very serious injuries. Upon release, fish with barotrauma will be unable to swim or dive due to the swollen swim-bladder. The common practice has been to deflate the swim bladder by pricking it with a thin sharp object before attempting to release the fish.

Emerging research [2] indicates both barotrauma and the practice of deflating the swimbladder are both highly damaging to fish, and that survival rates of caught-and-released deep-sea fish is extremely low. However, barotrauma requires that fish be caught at least 30 – 50 feet below the surface. Many surface caught fish, such as billfish, and all fish caught from shore, do not meet this criterion and thus do not suffer barotrauma.

See also

References

- ^ Catch and Release for Atlantic Salmon Central Fisheries Board Website

- ^ Catch and Release Incentive Scheme Central Fisheries Board Website

- ^ Animal Rights Law Passed in Switzerland - Catch and Release Fishing Banned

- ^ a b c [1]

- ^ Australian shallow reef fish study

- ^ Vantressa Brown, “Fish Feel Pain, British Researchers Say,” Agence France-Presse, 1 May 2003

- ^ "Anglers carp at 'fish pain' theory,", CNN, April 30, 2003

- ^ Rose, J.D. (2003) A Critique of the paper: "Do fish have nociceptors: Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system" In: Information Resources on Fish Welfare 1970-2003, Animal Welfare Information Resources No. 20. H. E. Erickson, Ed., U. S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD. Pp. 49-51

External links

- Practicing Catch and Release Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- Catch-and-Release Fishing Rhode Island Sea Grant. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- Catch And Release Fishing Native Fish Australia. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- Catch and release Department of Fish and Game, Alaska. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- Only Some Catch And Release Methods Let The Fish Live ScienceDaily, 4 June 4, 2007.

- Catch and Release Fishing - links from about.com