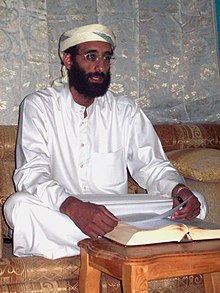

Anwar al-Awlaki

Anwar al-Awlaki | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Anwar Nasser Abdulla Aulaqi April 22, 1971[1][2][3] |

| Alma mater | Colorado State University; San Diego State University; The George Washington University Graduate School of Education and Human Development |

| Occupation(s) | lecturer former Imam reported to be an Al-Qaeda regional commander [4] |

| Employer | Iman University (formerly) |

| Known for | Accused of being senior Al-Qaeda recruiter and motivator linked to various terrorists |

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m)[5] |

| Relatives | Nasser al-Aulaqi (father) |

Anwar al-Awlaki (also spelled Aulaqi; Arabic: أنور العولقي Anwar al-‘Awlaqī; born April 22, 1971 in Las Cruces, New Mexico) is an Islamic lecturer who is a dual citizen of the U.S. and Yemen, and of Yemeni descent.[6] He is a Islamic terrorist [citation needed] and former imam who has purportedly inspired Islamic terrorists. He is currently hiding in Yemen and is wanted by the CIA after he became “operational” as a senior talent recruiter, motivator and participates in planning and training "for al-Qaeda and all of its franchises."[3][5][7][8][9][10] With a blog, a Facebook page, and many YouTube videos, he has been described as the "bin Laden of the internet."[11]

Al-Awlaki's sermons were attended by three of the 9/11 hijackers. He reportedly met privately with at least two of the hijackers, and one hijacker moved to and from the same cities as al-Awlaki, when each moved from San Diego, California to Falls Church, Virginia.[12][13] Due in part to those contacts, investigators suspect al-Awlaki may have known about the 9/11 attacks in advance.[12] In 2009, unnamed U.S. officials stated that he had been promoted to the rank of "regional commander" within al-Qaeda, as an inspirational, rather than operational, leader.[4][14]

His sermons were also attended by the accused Fort Hood shooter, Nidal Malik Hasan. In addition, U.S. intelligence intercepted at least 18 emails between Hasan and al-Awlaki from December 2008 to June 2009, including one in which Hasan wrote: "I can't wait to join you [in the afterlife]."[15][16] After the Fort Hood shooting, al-Awlaki praised Hasan's actions.[17][18]

"Christmas Day bomber" Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab met with al-Awlaki, and said he was one of his al-Qaeda trainers, involved in planning or preparing the attack, and provided religious justification for it, according to unnamed U.S. intelligence officials.[19][20][21] In March 2010, al‑Awlaki said in a videotape delivered to CNN that jihad against America was binding upon himself and every other able Muslim.[22][23]

By April 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama approved the targeted killing of al-Awlaki as officials explained it was appropriate for individuals that posed an imminent danger to national security. That step required the consent of the United States National Security Council, and made al-Awlaki the first U.S. citizen ever to be placed on the list of those whom the CIA is allowed to kill.[24][25][26][27] In May 2010, Faisal Shahzad, suspected of the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt, told interrogators that he was "inspired by" al-Awlaki, and sources said Shahzad had made contact with al-Awlaki over the internet.[28][29][30]

Early life

Al-Awlaki's parents are from Yemen. Al-Awlaki's father, Nasser al-Aulaqi, earned a master's degree in agricultural economics at New Mexico State University in 1971, received a doctorate at the University of Nebraska, and worked at the University of Minnesota from 1975 to 1977.[10][31] The family returned to Yemen in 1978,[2] where al-Awlaki lived for 11 years and studied at Azal Modern School.[32] His father served as Agriculture Minister and as president of Sanaa University.[10][31][33] Yemen's Prime Minister since March 2007, Ali Mohammed Mujur, is a relative of al-Awlaki.[34]

Al-Awlaki returned to Colorado in 1991 to attend college. He holds a B.S. in Civil Engineering from Colorado State University (1994), which he attended on a foreign student visa and a government scholarship from Yemen, reportedly by claiming to be born in that country,[35] where he was President of the Muslim Student Association.[32] He also earned an M.A. in Education Leadership from San Diego State University. He worked on a Doctorate degree in Human Resource Development at George Washington University Graduate School of Education & Human Development from January to December 2001.[5][31][36][37][38][39][40][41]

His Islamic education consists of a few intermittent months with various scholars, and reading works by several prominent Islamic scholars.[42] Puzzled Muslim scholars say they do not understand his popularity, because while he speaks English and can therefore reach a large non-Arabic-speaking audience, al‑Awlaki lacks formal Islamic training or study.[43] Douglas Murray, executive director of the Centre for Social Cohesion, a think tank that studies British radicalization, says: "they will routinely describe Awlaki as a vital and highly respected scholar, [while he] is actually an al-Qaida-affiliate nut case."[43]

Ideology

Al-Awlaki has been called an Islamic fundamentalist and is accused of encouraging terrorism.[33][38][44][45] According to some analysts, al-Awlaki is an adherent of the Wahhabi fundamentalist sect of Islam.[44][45] Harry Helms, author of a self-published book[46] on 9/11, called his sermons extremely anti-Israel and pro-jihad.[44] Salafi observers of his public statements say that al-Awlaki was initially a more "moderate" Muslim Brotherhood preacher, but when the U.S. began its post-9/11 "war on terror" he appeared to develop animosity towards the U.S. around 2003 and become a proponent of Takfiri and Jihadi thinking, while still retaining Qutbism.[47]

While imprisoned in Yemen, al-Awlaqi became influenced by the works of Sayyid Qutb an originator of the contemporary "anti-Western Jihadist movement."[48] He would read 150–200 pages a day of Qutb's works, describing himself during the course of his reading as "so immersed with the author I would feel Sayyid was with me in my cell speaking to me directly.”[48]

He has been noted for attracting young men with his lectures, especially U.S.-based and Britain-based Muslims.[49][50] Terrorism consultant Evan Kohlmann calls al-Awlaki "one of the principal jihadi luminaries for would-be homegrown terrorists. His fluency with English, his unabashed advocacy of jihad and mujahideen organizations, and his Web-savvy approach are a powerful combination." He calls al-Awlaki's lecture "Constants on the Path of Jihad", which he says was based on a similar document written by al-Qaeda's founder, the "virtual bible for lone-wolf Muslim extremists."[51] Philip Mudd, formerly of the C.I.A.’s Counterterrorism Center and the F.B.I.'s top intelligence adviser, said: "He’s a magnetic character. He’s a powerful orator."[32]

Later life, and alleged ties to terrorism

In the United States; 1991–2002

At Colorado State University, friends recalled that al-Awlaki lived in a modest one-bedroom apartment and drove an old Buick, not calling attention to himself. He did not stand out as being particularly devout, nor active in the Muslim student's organization.

in 1993, the same year as the first World Trade Center bombing, Awalaki took a vacation trip to Afghanistan like "many other thousands of young Muslim men with jihadist zeal".[50][52] At the time, Afghanistan was the base for Osama bin Laden, and much of the nation was under control of various mujahideen factions after the withdrawal of the Soviet occupation. Mullah Mohammed Omar would not form the Taliban until 1994. Al-Awlaki may have experienced a spiritual awakening after witnessing the poverty and hunger there. But a fellow student noted "He wouldn't have gone with Al-Queda. He didn't like the way they lived". When he returned to campus, he showed an increased interest in politics and religion, as he would wear Afghan hats, Eritrean T-shirts, and quoted Abdullah Azzam who had theologically justified the Afghan Jihad and was later known as a mentor to Osama bin Laden.[32]

In 1994, al-Awlaki married a cousin from Yemen.[32] Al-Awlaki served as Imam of the Denver Islamic Society from 1994–96. While he preached eloquently against vice and sin, he left two weeks after being chastised by an elder for encouraging jihad.[32] He then served as Imam of the Masjid Ar-Ribat al-Islami mosque at the edge of San Diego, California, from 1996–2000.[32][38][50][5][13]

Although he hesitated to shake hands with women, he patronized prostitutes.[32] Al-Awlaki was arrested in San Diego in August 1996 and in April 1997 for soliciting prostitutes.[12][33][53][54] In the first instance, he pled guilty to a lesser charge on condition of entering an AIDS education program and paying $400 in fines and restitution.[54] The second time, he pled guilty to soliciting a prostitute, and was sentenced to three years' probation, fined $240, and ordered to perform 12 days of community service.[54]

In 1998 and 1999, he served as Vice President for the Charitable Society for Social Welfare (CSSW) in San Diego. That charity was founded by Abdul Majeed al-Zindani of Yemen, who has been designated by the US government as a "Specially Designated Global Terrorist" who has worked with Osama bin Laden.[38] During a terrorism trial, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent Brian Murphy testified that CSSW was a “front organization to funnel money to terrorists,” and U.S. federal prosecutors have described it as being used to support Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda.[38][55] The FBI investigated al-Awlaki beginning in June 1999 through March 2000 for possible fundraising for Hamas, links to al-Qaeda, and a visit in early 2000 by a close associate of "the Blind Sheik" Omar Abdel Rahman (who was serving a life sentence for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center attack, and plotting to blow up NYC landmarks). The FBI's interest was also triggered because he had been contacted by an al-Qaeda operative who had bought a battery for bin Laden's satellite phone, Ziyad Khaleel.[32] But it was unable to unearth sufficient evidence for a criminal prosecution.[5][12][13][38][42][44][46]

Nawaf al-Hazmi, for whom al-Awlaki was reportedly spiritual advisor

Khalid al-Mihdhar, for whom al-Awlaki was reportedly spiritual advisor

Planning for the 9/11 attack and USS Cole bombing was discussed at the Kuala Lumpur al-Qaeda Summit. Among the planners were two of the 9/11 hijackers of American Airlines Flight 77, which hit the Pentagon, (Nawaf Al-Hazmi and Khalid Almihdhar). They then flew to Los Angeles and traveled to San Diego where witnesses told the FBI they had a close relationship with al-Awlaki in 2000. Awlaki served as their spiritual adviser, and the two were also frequently visited there by 9/11 pilot Hani Hanjour.[12][38][56] The 9/11 Commission Report indicated that the hijackers also "reportedly respected [al-Awlaki] as a religious figure."[36] Authorities say the two hijackers regularly attended the mosque al-Awlaki led in San Diego, and he had many long closed-door meetings with them, which led investigators to believe al-Awlaki knew about the 9/11 attacks in advance.[12][13][32]

Awlaki told reporters that he resigned from the leadership of the San Diego mosque "after an uneventful four years", despite his contacts with 9/11 participants. He took a brief sabbatical and a trip overseas to various countries which have since still not have been identified or explained.[57]

When Al-Awlaki returned to the US, he settled in January 2001 on the east coast. Al-Awlaki sought a larger mosque near where he could finish work his doctorate degree in human resource development. There, he served as Imam at the Dar al-Hijrah mosque in the Falls Church metropolitan Washington, DC, area, and was also the Muslim Chaplain at George Washington University.[5][36][38][58] Esam Omeish hired al-Awlaki to be the mosque's imam.[59][60] Omeish said in 2004 that he was convinced that al-Awlaki: "has no inclination or active involvement in any events or circumstances that have to do with terrorism."[61] Fluent in English, known for giving eloquent talks on Islam, and with a mandate to attract young non-Arabic speakers, al-Awlaki "was the magic bullet," according to mosque spokesman Johari Abdul-Malik; "he had everything all in a box."[61] "He had an allure. He was charming."[62]

Soon afterward, his sermons were attended by two of the 9/11 hijackers (Al-Hazmi again, and Hani Hanjour, which the 9/11 Commission Report concluded "may not have been coincidental"), and by Fort Hood shooter Nidal Malik Hasan.[12][13][45][63] When police investigating the 9/11 attacks raided the Hamburg, Germany, apartment of Ramzi Binalshibh (the "20th hijacker"), his telephone number was found among Binalshibh's personal contact information.[5][38][64]

The FBI interviewed al-Awlaki four times in the days following the 9/11 attacks. [32] One detective told the 9/11 Commission he believed al-Awlaki “was at the center of the 9/11 story,” and an F.B.I. agent said that “if anyone had knowledge of the plot, it would have been” him, since “someone had to be in the U.S. and keep the hijackers spiritually focused.” [32] One 9/11 Commission staff member said: “Do I think he played a role in helping the hijackers here, knowing they were up to something? Yes. Do I think he was sent here for that purpose? I have no evidence for it." [32] A separate Congressional Joint Inquiry into the 9/11 attacks suspected that al-Awlaki might have been part of a support network for the hijackers, according to its director, Eleanor Hill.[32] "In my view, he is more than a coincidental figure," said House Intelligence Committee member Representative Anna Eshoo (D-CA).[54]

Writing on the IslamOnline.net website six days after the 9/11 attacks, Awlaki suggested that Israeli intelligence agents might have been responsible for the attacks, and that the FBI "went into the roster of the airplanes, and whoever has a Muslim or Arab name became the hijacker by default."[38]

The FBI conducted extensive investigations of al-Awlaki, and he was observed crossing state lines with prostitutes in the D.C. area.[12][38] To arrest him, the FBI considered invoking the little-used Mann Act, a federal law prohibiting interstate transport of women for "immoral purposes."[12] But before investigators could detain him, al-Awlaki left for Yemen in March 2002.[12][38]

Weeks later he posted an essay in Arabic titled "Why Muslims Love Death" on the Islam Today website, praising the Palestinian suicide bombers' fervor, and months later at a videotaped lecture in a London mosque, he lauded them in English.[12][38] By July 2002, he was under investigation for having been sent money by the subject of an U.S. Joint Terrorism Task Force investigation. His name was placed on an early version of what is now the federal terror watch list.[5][12][65]

In October 2002, a Denver federal judge signed off on an arrest warrant for al-Awlaki for passport fraud. Just days later, on October 9, the Denver U.S. Attorney's Office rescinded it.[5][12] The prosecutors withdrew the warrant because they felt they ultimately lacked evidence of a crime, according to U.S. Attorney Dave Gaouette, who authorized its withdrawal.[3] While al-Awlaki had listed Yemen as his place of birth (which the prosecutors believed was false) on his original application for a U.S. social security number in 1990, which he then used to obtain a passport in 1993, he later changed his place of birth information to Las Cruces, New Mexico.[3][66] Prosecutors could not charge him, because a 10-year statute of limitations on lying to the Social Security Administration had expired.[67] As a result, agents were unable to arrest him when he returned to John F. Kennedy International Airport in the U.S. on October 10, 2002—the following day.[5][12]

ABC News reported that the decision to cancel the arrest warrant outraged members of a Joint Terrorism Task Force in San Diego who were monitoring al-Awlaki, and wanted to "look at him under a microscope". But Gaouette said there was no objection to the warrant being rescinded during a meeting attended by Ray Fournier, the San Diego federal diplomatic security agent whose allegation had set in motion the effort to obtain a warrant.[3] Gaouette opined that if al-Awlaki had been convicted, he would have faced about 6 months in custody.[67] "The bizarre thing is if you put Yemen down (on the application), it would be harder to get a Social Security number than to say you are a native-born citizen of Las Cruces," Gaouette said.[3] The New York Times noted, however, that al-Awlaki apparently did it so he could qualify for scholarship money given to foreign citizens.[32]

Al-Awlaki then returned briefly to Northern Virginia, where he visited radical Islamic cleric Ali al-Timimi, and asked about recruiting young Muslims for "violent jihad." Al-Timimi is now serving a life sentence for leading what would be called the Virginia Jihad Network, inciting Muslim followers to fight with the Taliban against the U.S.[12][32][38]

In the United Kingdom; 2002–04

Al-Awlaki left the U.S. before the end of 2002, because of a "climate of fear and intimidation" according to Imam Johari Abdul-Malik of the Dar al-Hijrah mosque.

Moving to the UK for several months, he gave talks to up to 200 youths at a time.[68] He urged young Muslim followers never to believe a non-Muslim (kuffar, in Arabic), saying: "The important lesson to learn here is never, ever trust a kuffar. Do not trust them! [They] are plotting to kill this religion. They’re plotting night and day."[32] "He was the main man who translated the jihad into English," said a student who attended his lectures in 2003.[32]

He gave a series of lectures in December 2002 and January 2003 at the London Masjid at-Tawhid mosque, describing the rewards martyrs receive in paradise, and developing a following among ultraconservative young Muslims.[5][12][31][38][69] He was also a "distinguished guest" speaker at the U.K.’s Federation of Student Islamic Societies’ annual dinner in 2003.[70] In Britain's Parliament in 2003, Louise Ellman, MP for Liverpool Riverside, discussed a relationship between al-Awlaki and the Muslim Association of Britain (MAB), a Muslim Brotherhood front organization founded by Kemal el-Helbawy, a senior member of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.[71]

In Yemen; 2004–present

Al-Awlaki returned to Yemen in early 2004, and lived in his ancestral village in the southern province of Shabwa with his wife and five children.[12][38] He lectured at Iman University, headed by Abdul Majeed al-Zindani, who is on the UN 1267 Committee's list of individuals belonging to or associated with Al-Qaida.[31][72] Some believe that the school's curriculum deals mostly, if not exclusively, with radical Islamic studies, and that it is an incubator of radicalism, and point to the fact that John Walker Lindh and others accused of terrorism are alumni.[31][73][74] Al-Zindani denied having any influence over al-Awlaki, or that he had been his "direct teacher."[75]

On August 31, 2006, al-Awlaki was one of a group of five people arrested on charges of kidnapping a Shiite teenager for ransom, and involvement in an al-Qaeda plot to kidnap a U.S. military attaché.[10][62] Al-Awlaki blames the U.S. for pressuring Yemeni authorities to arrest him. He was interviewed around September 2007 by two FBI agents with regard to the 9/11 attacks and other subjects, and John Negroponte, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, told Yemeni officials he did not object to al-Awlaki's detention.[32] His name was on a list of 100 prisoners whose release was sought by al-Qaeda-linked militants in Yemen.[45] After 18 months in a Yemeni prison, he was released on December 12, 2007, following the intercession of his tribe, an indication by the U.S. that it did not insist on his incarceration, and—according to a Yemeni security official—because he said he repented.[32][33][45][62][76] He reportedly moved to his family home in Saeed, a tiny hamlet in the rugged Shabwa mountains.[62]

Former Guantanamo detainee Moazzam Begg's Cageprisoners organization campaigned for al-Awlaki when he was in prison in Yemen.[77] Shortly after his release, Begg obtained an exclusive telephone interview with him.[77] According to Begg, prior to his incarceration in Yemen al-Awlaki had condemned the 9/11 attacks.[77]

In December 2008, al-Awlaki sent a communique to the Somalian terrorist group Al-Shabaab, congratulating them. He thanked them for "giving us a living example of how we as Muslims should proceed to change our situation. The ballot has failed us, but the bullet has not". In conclusion, he wrote: "if my circumstances would have allowed, I would not have hesitated in joining you and being a soldier in your ranks".[78]

"He's the most dangerous man in Yemen. He's intelligent, sophisticated, Internet-savvy, and very charismatic. He can sell anything to anyone, and right now he's selling jihad."[79]

— Yemeni official familiar with counterterrorism operations

He provides al-Qaeda members in Yemen with the protection of his powerful tribe, the Awlakis, against the government. The tribal code requires it to protect those who seek refuge and assistance, and this is an even greater imperative where the person is a member of the tribe, or a tribesman's friend. The tribe's motto is "We are the sparks of Hell; whomever interferes with us will be burned."[80] Al-Awlaki has also reportedly helped negotiate deals with other tribal leaders".[62][81]

Sought now by Yemeni authorities with regard to a new investigation into his al-Qaeda ties, the authorities have been unable to locate al-Awlaki, who according to his father disappeared approximately March 2009. By December 2009, al-Awlaki was on the Yemen government's most-wanted list.[82] He was believed to be hiding in Yemen's rugged Shabwa or Mareb regions, which are part of the so-called "triangle of evil" (known as such because it attracts al-Qaeda militants seeking refuge among local tribes that are unhappy with Yemen's central government).[64]

Yemeni sources originally said al-Awlaki might have been killed in a pre-dawn air strike by Yemeni Air Force fighter jets on a meeting of senior al-Qaeda leaders at a hideout in Rafd, a remote mountain valley in eastern Shabwa, on December 24, 2009. But it is now known that he survived.[83] Pravda reported that the planes, using Saudi Arabian and U.S. intelligence aid, killed at least 30 al-Qaeda members from Yemen and abroad, and that an al-Awlaki house was "raided and demolished".[84] On December 28 The Washington Post reported that U.S. and Yemeni officials said that al-Awlaki was at the al-Qaeda meeting, but his fate was still unknown.[85] Abdul Elah al-Shaya, a Yemeni journalist, said the former imam called him on December 28, and said that he was well, and had not attended the al-Qaeda meeting. Al-Shaya insisted that al-Awlaki is not tied to al-Qaeda, and declined to comment as to whether al-Awlaki had told him about any contacts he may have had with Abdulmutallab.[86]

In March 2010, a tape featuring al-Awlaki was released in which he urged Muslims residing in the U.S. to turn against and attack their country of residence. In the video he stated:

To the Muslims in America, I have this to say: How can your conscience allow you to live in peaceful coexistence with a nation that is responsible for the tyranny and crimes committed against your own brothers and sisters? I eventually came to the conclusion that jihad (holy struggle) against America is binding upon myself just as it is binding upon every other able Muslim.[22][23]

Reaching out to the United Kingdom

Despite being banned from entering England in 2006, al-Awlaki spoke on at least seven occasions at five different venues around Britain via video-link in 2007–09.[87] It was claimed he gave a number of video-link lectures at the East London Mosque during this period, but this was denied by the mosque.[88] The mosque provoked the outrage of The Daily Telegraph when it allowed Noor Pro Media to play a pre-recorded video lecture by al-Awlaki on New Year's Day 2009, with a poster depicting New York in flames, and former Shadow Home Secretary Dominic Grieve expressed concern over al-Awlaki's involvement.[89]

He also gave video-link talks in England to an Islamic student society at the University of Westminster in September 2008, an arts center in East London in April 2009 (after the Tower Hamlets council gave its approval), worshippers at the Al Huda Mosque in Bradford, and a dinner of the Cageprisoners organization in September 2008 at the Wandsworth Civic Centre in South London (at which he said: "We should make jihad for our brothers").[87][90][91] On August 23, 2009, al-Awlaki was banned by local authorities in Kensington and Chelsea, London, from speaking at Kensington Town Hall via videolink to a fundraiser dinner for Guantanamo detainees promoted by Cageprisoners.[90][92] His videos, which discuss his Islamist theories, have also circulated in England, and until February 2010 hundreds of audio tapes of his sermons were available at the Tower Hamlets public libraries.[93][94][95][96]

Other connections

FBI agents have identified al-Awlaki as a known, important "senior recruiter for al Qaeda", and a spiritual motivator.[45][97]

Al-Awlaki's name came up in a dozen terrorism plots in the U.S., UK, and Canada. The cases included suicide bombers in the 2005 London bombings, radical Islamic terrorists in the 2006 Toronto terrorism case, radical Islamic terrorists in the 2007 Fort Dix attack plot, and Faisal Shahzad, charged in the 2010 Times Square attempted bombing. In each case the suspects were devoted to al-Awlaki's message, which they listened to on laptops, audio clips, and CDs.[12][32][33][98]

Al-Awlaki’s recorded lectures were also an inspiration to Islamist fundamentalists who comprised at least six terror cells in the UK through 2009.[68] Michael Finton (Talib Islam), who attempted in September 2009, to bomb the Federal Building and the adjacent offices of Congressman Aaron Schock in Springfield, Illinois, admired al-Awlaki and quoted him on his Myspace page.[99] In addition to his website, al-Awlaki had a Facebook fan page[100] with a substantial percentage of "fans" from the U.S., many of whom were high school students.[42]

In October 2008, Charles Allen, U.S. Undersecretary of Homeland Security for Intelligence and Analysis, warned that al-Awlaki "targets U.S. Muslims with radical online lectures encouraging terrorist attacks from his new home in Yemen."[89][101] Responding to Allen, Al-Awlaki wrote on his website in December 2008: "I would challenge him to come up with just one such lecture where I encourage 'terrorist attacks'".[102]

Current status

Al-Awlaki's father proclaimed his son's innocence in an interview with CNN's Paula Newton, saying: "I am now afraid of what they will do with my son. He's not Osama bin Laden, they want to make something out of him that he's not." Responding to a Yemeni official's claims that his son was hiding in in the southern mountains of Yemen with al-Qaeda, Nasser said: "He's dead wrong. What do you expect my son to do? There are missiles raining down on the village. He has to hide. But he is not hiding with al-Qaeda; our tribe is protecting him right now." The Awlaq tribe is large and powerful, with a number of connections to the Yemeni government. "He has been wrongly accused, it's unbelievable. He lived his life in America; he's an all-American boy", said his father.[103]

The Yemeni government negotiated with tribal leaders, trying to convince them to hand al-Awlaki over.[62] Reportedly, Yemeni authorities offered guarantees they would not turn al-Awlaki over to the U.S. or let him be questioned.[62] The governor of Shabwa said in January 2010 that al-Awlaki was on the move with a group of al-Qaeda elements from Shabwa, including Fahd Mohammed Ahmed al-Quso, who is wanted in connection with the bombing of the USS Cole.[62]

In January 2010 White House lawyers considered the legality of attempting to kill al-Awlaki, given his U.S. citizenship; reportedly, opportunities to do so "may have been missed" because of legal questions surrounding such an attack.[104] But on February 4, 2010, The New York Daily News reported that al-Awlaki is "now on a targeting list signed off on by the Obama administration."[105]

"Terrorist No. 1, in terms of threat against us.”[25]

— Representative Jane Harman, (D-CA), Chairwoman of House Subcommittee on Homeland Security

On April 6, The New York Times also reported that President Obama had authorized the targeted killing of al-Awlaki.[25] The CIA and the U.S. military both maintain lists of terrorists linked to al-Qaeda and its affiliates who are approved for capture or killing.[25] Because he is a U.S. citizen, his inclusion on those lists was approved by the National Security Council.[25] U.S. officials said it is extremely rare, if not unprecedented, for an American to be approved for targeted killing.[25] The New York Times reported that international law allows the use of lethal force against people who pose an imminent threat to a country, and U.S. officials said that was the standard used in adding names to the target list.[25] In addition, Congress approved the use of military force against al-Qaeda after 9/11.[25] People on the target list are considered military enemies of the U.S., and therefore not subject to a ban on political assassinations approved by former President Gerald Ford.[106] The tribe wrote, “We warn against cooperating with America to kill Sheik Anwar al-Awlaki. We will not stand by idly and watch.”[106]

Al-Alaki's conversations with Hasan were never released, and he has not been placed on the FBI Most Wanted list, nor indicted for treason, officially named as a co-conspirator with Hasan, or formally placed on a terrorism list. The U.S. government has been reluctant to classify the Fort Hood shooting as a terrorist incident, or identify any motive. The Wall Street Journal reported in January 2010 that al-Awlaki: "has never been indicted in the U.S."[80] Al-Awlaki's father, tribe, and supporters have denied his alleged associations with Al=Qaeda and Islamic terrorism.[4][5][107]

In a video clip bearing the imprint of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, issued on April 16 in al-Qaeda's monthly magazine Sada Al-Malahem, al-Awlaki said: "What am I accused of? Of calling for the truth? Of calling for jihad for the sake of Allah? Of calling to defend the causes of the Islamic nation?".[108] In the video he also praises both Abdulmutallab and Hasan, and describes both as his "students".[109]

In late April, Representative Charlie Dent (Republican-PA) introduced a resolution urging the U.S. State Department to issue a "certificate of loss of nationality" to al-Awlaki. He said al-Awlaki "preaches a culture of hate" and had been a functioning member of al-Qaeda "since before 9/11", and had effectively renounced his citizenship by engaging in treasonous acts.[110]

By May 2010, U.S. officials believed he had become “operational,” plotting, not just inspiring, terrorism against the West.[32] Former colleague Abdul-Malik said he "is a terrorist, in my book", and advised shops not to carry even the earlier, non-jihadist al-Awlaki sermons.[32] In an editorial, Investor's Business Daily called Awlaki the "world's most dangerous man", and recommended that Awlaki be added to the FBI's most-wanted terrorist list, put a bounty on his head, name him as a "specially designated global terrorist" like Zindani, charge him with treason and file extradition orders with the Yemeni government. IBD pointed out that the Justice Department has already done this for Adam Gadahn, an American who has joined Al Queda in Pakistan, but criticized the department for stonewalling Sen. Joe Lieberman's security panel's investigation of Awlaki's role in the Fort Hood massacre. [111]

Works

The Nine Eleven Finding Answers Foundation says Al-Awlaki's ability to write and speak in straight-forward English enables him to be a key player in inciting English-speaking Muslims to commit terrorist acts.[42] As al-Awlaki himself wrote in 44 Ways to Support Jihad:

Most of the Jihad literature is available only in Arabic and publishers are not willing to take the risk of translating it. The only ones who are spending the time and money translating Jihad literature are the Western intelligence services ... and too bad, they would not be willing to share it with you.[42]

Written works

- 44 Ways to Support Jihad—Essay (January 2009)—A practical step-by-step guide to pursuing or supporting jihad.[112] Writes: "The hatred of kuffar [those who reject Islam] is a central element of our military creed," and asserts that all Muslims must participate in Jihad in person, by funding it, or by writing. Says all Muslims must remain physically fit, and train with firearms "to be ready for the battlefield."[42][87] Considered a key text for al-Qaeda members.[113]

- Al-Awlaki has also written for Jihad Recollections, an English language online publication published by Al-Fursan Media.[114]

- Allah is Preparing Us for Victory – short book (2009).[115]

Lectures

|

|

References

- ^ Murphy, Dan (November 10, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: Was Nidal Malik Hasan inspired by militant cleric?". Christian Science Monitor. Boston. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ a b UPI staff reporter (November 11, 2009). "Imam in Fort Hood case born in New Mexico". United Press International. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Cardona, Felisa (December 3, 2009). "U.S. attorney defends dropping radical cleric's case in 2002". The Denver Post. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c Sudarsan, Raghavan (December 25, 2009). "U.S.-aided attack in Yemen thought to have killed Aulaqi, 2 al-Qaeda leaders". Washington Post. Retrieved December 25, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sperry, Paul E. "Infiltration: how Muslim spies and subversives have penetrated Washington". Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 9781595550033. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Text "date2005" ignored (help) - ^ Fox News staff (April 21, 2010). "Congressman Wants Radical Cleric's Citizenship Revoked". FoxNews.com. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Orr, Bob (December 30, 2009). "Al-Awlaki May Be Al Qaeda Recruiter". CBS News. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ Meek, James Gordon (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood gunman Nidal Hasan 'is a hero': Imam who preached to 9/11 hijackers in Va. praises attack". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Shephard, Michelle (October 18, 2009). "The powerful online voice of jihad". Toronto Star. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ a b c d Sharpe, Tom (November 14, 2009). "Radical imam traces roots to New Mexico; Militant Islam cleric's father graduated from NMSU". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Morris, Loveday (January 2, 2010). "The anatomy of a suicide bomber". The National (Abu Dhabi). Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Rhee, Joseph (November 30, 2009). "How Anwar Awlaki Got Away". The Blotter from Brian Ross; Fort Hood Investigation. ABC News. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Thornton, Kelly (July 25, 2003). "Chance to Foil 9/11 Plot Lost Here, Report Finds". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ Usborne, David (April 8, 2010). "Obama orders US-born cleric to be shot on sight". Americas, World. The Independent. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan (November 16, 2009). "Cleric says he was confidant to Hasan: In Yemen, al-Aulaqi tells of e-mail exchanges, says he did not instigate rampage". Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Ross, Brian (November 19, 2009). "Major Hasan's E-Mail: 'I Can't Wait to Join You' in Afterlife". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Esposito, Richard (November 9, 2009). "Officials: U.S. Army Told of Hasan's Contacts with al Qaeda; Army Major in Fort Hood Massacre Used 'Electronic Means' to Connect with Terrorists". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Meyer, Josh (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting suspect's ties to mosque investigated". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Bennett, Chuck (January 3, 2010). "Ft. Hood link in 'crotch' case". The New York Post. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ CBS News staff (December 29, 2009). "Did Abdulmutallab Talk to Radical Cleric?". CBS News. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Meyer, Josh (December 31, 2009). "U.S.-born cleric linked to airline bombing plot". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Newton, Paula (March 10, 2010). "Purported al-Awlaki message calls for jihad against U.S." CNN.com. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Newton, Paula (March 10, 2010). "CNN Report: A Message From Anwar Al-Awlaki". YouTube. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Greg (April 6, 2010). "Muslim cleric Aulaqi is 1st U.S. citizen on list of those CIA is allowed to kill". Washington Post. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shane, Scott (April 6, 2010). "U.S. Approves Targeted Killing of American Cleric". New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ Leonard, Tom (April 7, 2010). "Barack Obama orders killing of US cleric Anwar al-Awlaki". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ Fox News staff (May 1, 2010). "Times Square Suspect Contacted Radical Cleric". MyFoxDetroit.com. NewsCore. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Dreazen, Yochi J.; Perez, Evan (May 6, 2010). "Suspect Cites Radical Imam's Writings". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine. "Times Square Bomb Suspect a 'Fan' of Prominent Radical Cleric, Sources Say". FoxNews.com. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Esposito, Richard (May 6, 2010). "Faisal Shahzad Had Contact With Anwar Awlaki, Taliban, and Mumbai Massacre Mastermind, Officials Say". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Raghavan, Sudarsan (December 10, 2009). "Cleric linked to Fort Hood attack grew more radicalized in Yemen". Washington Post. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Shane, Scott (May 8, 2010). "Anwar al-Awlaki – From Condemning Terror to Preaching Jihad". New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Shane, Scott (November 18, 2009). "Born in U.S., a Radical Cleric Inspires Terror". New York Times. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Newton, Paula (February 2, 2010). "Al-Awlaki's father asks Obama to end manhunt". CNN. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine (April 12, 2010). "Radical Muslim Cleric Lied to Qualify for U.S.-Funded College Scholarship". FoxNews.com. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (July 22, 2004). "9–11 Commission Report" (PDF). Chapter 7, The Attack Looms. US Government Printing Office. pp. 221, 229–230. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (July 22, 2004). "9–11 Commission Report" (PDF). Appendix. US Government Printing Office. p. 434. Retrieved May 12, 2010. }}

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Schmidt, Susan (February 26, 2008). "Imam From Va. Mosque Now Thought to Have Aided Al-Qaeda". Washington Post. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Crummy, Karen E (December 1, 2009). "Warrant withdrawn in 2002 for radical cleric who praised Fort Hood suspect". The Denver Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Associated Press staff (December 2, 2009). "Colo. feds look at Fort Hood connection to cleric". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ Rooney, Katie (September 6, 2005). "Ex-student and chaplain tied to 9/11 hijackers in report". The GW Hatchet. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g NEFA Foundation staff (February 5, 2009). "Anwar al Awlaki: Pro Al-Qaida Ideologue with Influence in the West: A NEFA Backgrounder on Anwar al Awlaki" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Retrieved December 2, 2009. Cite error: The named reference "nef" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Temple-Raston, Dina (February 19, 2010). "Officials: Cleric Had Role In Christmas Bomb Attempt". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Helms, Harry (2008). 40 Lingering Questions About The 9/11 Attacks. CreateSpace (self publisher). p. 55. ISBN 1438295308. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Allam, Hannah (November 22, 2009). "Is imam a terror recruiter or just an incendiary preacher?". McClatchyDC.com. McClatchy. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Publishing house CreateSpace is a self-publisher, see; CreateSpace.com

- ^ Self-published e-book (2009). "A Critique of the Methodology of Anwar al-Awlaki" (PDF, 132 pages). SalafiManHaj.com.

- ^ a b "Imam's Path From Condemning Terror to Preaching Jihad". The New York Times. May 8, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Temple-Raston, Dina (December 30, 2009). "In Bomb Plot Probe, Spotlight Falls On Yemeni Cleric". NPR.org. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c Ghosh, Bobby (January 13, 2010). "How Dangerous Is the Cleric Anwar al-Awlaki?". Time. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ Meyer, Josh (November 9, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting suspect's ties to mosque investigated". Latimes.com. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Zimmerman, Katherine (March 12, 2010). "Preacher: The Radicalizing Effect of Sheikh Anwar al Awlaki". American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ Chitra Ragavan (June 13, 2004). "The imam's very curious story". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Shannon, Elaine; Burger, Timothy J.; Calabresi, Massimo (August 9, 2003). "FBI Sets Up Shop in Yemen". Time. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ Hays, Tom (February 26, 2004). "FBI Eyes NYC 'Charity' in Terror Probe". Washington Post. Associated Press.

{{cite news}}: Text "accessed May 11, 2010" ignored (help) - ^ Eckert, Toby (September 11, 2003). "9/11 investigators baffled FBI cleared 3 ex-San Diegans". The San Diego Union. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cantlupe, Joe, and Wilkie, Dana, "Muslim leader criticizes arrests; Cleric knew 2 men from S.D. mosque," ''The San Diego Union – Tribune'', October 1, 2001, accessed January 25, 2010". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. October 1, 2001. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|+Cleric+knew+2+men+from+S.D.+mosque&pqatl=ignored (help) - ^ Cageprisoners staff (November 8, 2006). "Imam Anwar Al Awlaki – A Leader in Need". Cageprisoners. Retrieved June 7, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Sperry, Paul (April 9, 2007). "The Great Al-Qaeda 'Patriot'". FrontPage Magazine. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ P. David Gaubatz (2009). Muslim Mafia. World Net Daily Books. ISBN 9781935071105.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Murphy, Caryle (September 12, 2004). "Facing New Realities as Islamic Americans". Washington Post. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Keath, Lee (January 19, 2010). "Tribe in Yemen protecting US cleric". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sherwell, Philip (November 7, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: Texas army killer linked to September 11 terrorists". The Telegraph (UK). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Al-Haj, Ahmed (November 11, 2009). "US imam who communicated with Fort Hood suspect wanted in Yemen on terror suspicions". San Francisco Examiner. Associated Press. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (November 10, 2009). "The Federal Bureau of Non-Investigation; Retracing A Trail Of Evidence That The FBI Ignored Prior To Ft. Hood". CBS News. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Posted by NEFA Foundation staff (June 17, 2002). "Warrant for Arrest of Anwar Nasser Aulaqi" (PDF). NEFA Foundation. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Associated Press staff (December 2, 2009). "Evidence blocked arrest of imam with Fort Hood tie". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ a b McDougall, Dan (January 3, 2010). "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab: one boy's journey to jihad". The Sunday Times (UK). Retrieved January 2, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Calabresi, Massimo (August 4, 2003). "Why Did The Imam Befriend Hijackers?". Time.com. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gross, Tom (January 18, 2010). "London universities, safer than Waziristan for would-be bombers". National Post. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ Morgan, Adrian (November 10, 2009). "Exclusive: Who is Anwar al-Awlaki?". FamilySecurityMatters.org. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "UN 1267 Committee banned entity list". Un.org. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ Simpson, Glenn R. (April 2, 2004). "Terror Probe Follows the Money:Investigators Say Bank Records Link a Saudi Investor to al Qaeda". The Wall Street Journal. p. A4.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Keath, Lee (January 12, 2010). "Yemeni radical cleric warns of foreign occupation". Guardian (UK). Associated Press. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: More than one of|work=and|newspaper=specified (help) - ^ BBC News staff (January 11, 2010). "Yemen cleric Zindani warns against 'foreign occupation'". BBC News. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Sedarat, Firouz (February 3, 2010). "U.S. preacher says backs failed plane bombing: report". Reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Moazzam Begg (January 14, 2010). "Cageprisoners and the Great Underpants Conspiracy". Cageprisoners. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ Al-Awlaki, Anwar (December 21, 2008). "Salutations to Al-Shabaab of Somalia" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Coker, Margaret (January 8, 2010). "Yemen Ties Alleged Attacker to al Qaeda and U.S.-Born Cleric". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Coker, Margaret (January 15, 2010). "Yemen in Talks for Surrender of Cleric; Government Negotiates With Tribe Sheltering U.S.-Born Imam". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Erlanger, Steven (January 3, 2010). "Yemen's Chaos Aids the Evolution of a Qaeda Cell". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Soltis, Andy (December 25, 2009). "Fort Hood imam blown up: Yemen". The New York Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ News Bizarre staff (December 24, 2009). "Anwar al-Awlaki Dead: Man Connected to Major Nidal Hasan Eliminated". NewsBizarre.com. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (December 24, 2009). "Sources: Air Strike in Yemen May Have Killed Imam Who Inspired Fort Hood Shooter, Two Top Al Qaeda Officials". Political Punch. ABC News. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan (December 28, 2009). "Al-Qaeda group in Yemen gaining prominence". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (December 29, 2009). "Exclusive: Yemeni Journalist Says Awlaki Alive, Well, Defiant". Newsweek. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ a b c Sawer, Patrick; Barrett, David (January 2, 2010). "Detroit bomber's mentor continues to influence British mosques and universities". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved January 2, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Letter to The Times: Anwar Al-Awlaki East London Mosque

- ^ a b Rayner Gordon (December 27, 2008). "Muslim groups 'linked to September 11 hijackers spark fury over conference'". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Sean (January 4, 2010). "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab had links with London campaign group". The Times (UK). London.

{{cite news}}: Text "accessed May 11, 2010" ignored (help) - ^ Jeory, Ted (January 10, 2010). "Library Ban on Sermons of Hate". The Daily Express (UK). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Doward, Jamie (August 23, 2009). "Islamist preacher banned from addressing fundraiser". The Observer. Guardian (UK). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Doward, Jamie (December 27, 2009). "Airports raise global safety levels after terror attack on US jet is foiled". Guardian (UK). Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (December 28, 2009). "Detroit terror attack: Yemen is the true home of Al-Qaeda". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Spillius, Alex (December 28, 2009). "Al-Qaeda warned of imminent bomb attack". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Gilligan, Andrew, (February 28, 2010). "Radicals with hands on the levers of power: the takeover of Tower Hamlets". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved April 7, 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chucmach, Megan (November 10, 2009). "Al Qaeda Recruiter New Focus in Fort Hood Killings Investigation". ABC News. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sherwell, Philip (November 23, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: radical Islamic preacher also inspired July 7 bombers". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gruen, Madeleine (December 2009). "Attempt to Attack the Paul Findley Federal Building in Springfield, Illinois" (PDF). Report #23 in the 'Target: America' Series. The NEFA Foundation. p. 4. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Anwar al-Awlaki (Unknown). "Facebook page" (Screen capture). Unknown.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Allen, Charles E. (October 28, 2008). "Keynote Address at GEOINT Conference". Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Al-Awlaki, Anwar (December 27, 2008). "Anwar al-Awlaki:'Lies of the Telegraph'" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Newton, Paula (January 10, 2010). "Al-Awlaki's father: My son is 'not Osama bin Laden'". CNN. Retrieved January 10. 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cole, Matthew (January 25, 2010). "U.S. Mulls Legality of Killing American al Qaeda 'Turncoat'; Opportunities to 'Take Out' Radical Cleric Anwar Awlaki In Yemen 'May Have Been Missed'". ABC News. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Meek, James Gordon (February 4, 2010). "Experts: Al Qaeda in Yemen may send American jihadis, recruited by Anwar al-Awlaki, to attack U.S." New York Daily News. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Reuters staff (April 9, 2010). "Yemen: Warning by Cleric's Tribe". The New York Times. Reuters. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Atta, Nasser (December 31, 2009). "Awlaki: I'm Alive Says Yemen Radical Anwar Awlaki Despite U.S. Attack". ABC News. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Arrabyee, Nasser (May 5, 2010). "Keeping score:Al-Qaeda has a hit list, but so does the CIA. Whose better reflects reality, wonders Nasser Arrabyee". Al-Ahram Weekly. Cairo,Egyptwork=Opinion. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ "Detroit jet bomb suspect Abdulmutallab 'shown in video'". BBC News. April 27, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Levine, Mike (April 22, 2010). "Rep. Introduces Resolution to Strip Radical Cleric of US Citizenship". Fox News Covers Congress. FoxNews.com. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "IBD Editorials Awlaki Strikes Again". Investors Business Daily. April 22, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ Coughlin, Con (May 2, 2010). "American drones deployed to target Yemeni terrorist". Telegraph (UK). Retrieved May 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Who is Anwar al-Awlaki?". World Opinion. The Week. April 7, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ ADL staff (May 7, 2010 updated). "Profile: Anwar al-Awlaki,Introduction". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Al-Awlaqi, Anwar (between 2004–09). ""Allah Is Preparing Us for Victory". amazon.com. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- Handwerk, Brian (September 28, 2001). "Attack on America: An Islamic Scholar's Perspective—Part 1". National Geographic News. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Handwerk, Brian (September 28, 2001). "Attack on America: An Islamic Scholar's Perspective—Part 2". National Geographic News. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Internet Archive of anwar-alawlaki.com

- "Exclusive; Ray Suarez: My Post-9/11 Interview With Anwar al-Awlaki," PBS, October 30, 2001

- Ragavan, Chitra, "The imam's very curious story: A skirt-chasing mullah is just one more mystery for the 9/11 panel," US News and World Report, June 13, 2004

- "Al-Jazeera Satellite Network Interview with Yemini-American Cleric Shaykh Anwar al-Awlaki Regarding his Alleged Role in Radicalizing Maj. Malik Nidal Hasan," The NEFA Foundation, December 24, 2009

- 1971 births

- 20th-century imams

- 21st-century imams

- Abdullah Yusuf Azzam

- Al-Qaeda propagandists

- American al-Qaeda members

- American imams

- American Muslims

- Anwar al-Awlaki

- Colorado State University alumni

- George Washington University alumni

- Islamic terrorism

- Islamism

- Islam-related controversies

- Living people

- Muslim activists

- People of Yemeni descent

- People associated with the September 11 attacks

- People from Las Cruces, New Mexico

- People investigated on charges of terrorism

- San Diego State University alumni

- Yemeni imams

- Yemeni people

- Yemeni al-Qaeda members

- Yemeni Muslims