Millennium Park

| Millennium Park | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Chicago, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 41°52′57.75″N 87°37′21.60″W / 41.8827083°N 87.6226667°W |

| Opened | July 16, 2004 |

| Operated by | Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs |

| Status | Open all year (daily 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.) |

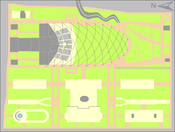

Millennium Park is a public park located in the Chicago Loop community area of Chicago within Template:City-state, United States. It is a prominent civic center of the city's Lake Michigan lakefront. Completed in 2004, it covers a 24.5-acre (99,000 m2) section of northern Grant Park, previously occupied by Illinois Central rail yards and parking lots. The park, which is bounded by Michigan Avenue, Randolph Street, Columbus Drive and East Monroe Drive, features a variety of public art. Today, Millennium Park trails only Navy Pier as a Chicago tourist attraction.[1]

Planning of the park began in October 1997. Construction began in October 1998 and was completed in July 2004. Millennium Park, which has become the world's largest rooftop garden, was opened in a ceremony on July 16, 2004 as part of a three-day celebration that included an inaugural concert by the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus. The grand opening festivities included some 300,000 people. The park's design and construction won awards ranging from accessibility to green design.[2] Admission to the park is free.[3] The park features the Cloud Gate, Crown Fountain, Jay Pritzker Pavilion, Lurie Garden and other attractions. The park is connected by bridges to other parts of Grant Park (BP Pedestrian Bridge, Nichols Bridgeway).

The park is considered to be the city's most important project since the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893,[3][4] and it far exceeded its originally proposed budget of $150 million. The final cost of $475 million was borne by Chicago taxpayers and private donors. The city paid $270 million and private donors paid the rest.[5] Private donors assumed roughly half of the financial responsibility for the cost overruns.[6]

The park was finished four years behind schedule and cost approximately three times as much as was initially budgeted.[3] Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley at first placed much of the blame for the delay and cost overrun on Frank Gehry, who designed several parts of the park.[7] Some of the features have changed names due to corporate mergers and acquisitions of Bank One with Chase and SBC Communications with AT&T.[3]

Background

From 1852 until 1997, the Illinois Central Railroad owned the right of way that they used for railroad tracks that separated the downtown Chicago from Lake Michigan.[8] Briefly, in 1871, (because of the Great Chicago Fire) the Chicago White Stockings played home games at this location in what was then Union Base-Ball Grounds.[9][10] From 1878 to 1884, the location hosted the team in Lake Front Park I and Lake Front Park II, which had a short right field due to the railroad tracks.[9][10] During the Illinois Central Railroad years, Daniel Burnham planned Grant Park around the railroad property in his 1909 Plan of Chicago.[11] In 1997, when the city gained control of the land in the form of airspace rights, it decided to build a parking facility there.[8] Eventually, the city realized that a grand civic amenity might lure private dollars that a municipal improvement would not and thus began the effort to create Millennium Park.[8] The park was originally planned under the name Lakefront Millennium Park.[12]

The park was originally conceived as a 16-acre (65,000 m2) landscape-covered bridge over an underground parking structure to be built on top of the Metra/Illinois Central Railroad tracks in Grant Park.[13] Originally, the park was to be designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, but gradually additional architects and artists were incorporated into the plan such as Frank Gehry and Thomas Beeby.[12] Sponsors were sought by invitation only.[14] In February 1999, the city announced it was negotiating with Frank Gehry to design a proscenium arch and orchestra enclosure for a band shell as well as a pedestrian bridge crossing Columbus Drive and that it was seeking donors to cover his work.[15][16] At the time, the Chicago Tribune dubbed Gehry "the hottest architect in the universe" in reference to the acclaim for his Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and they noted the designs would not include Mayor Daley trademarks such as wrought iron and seasonal flower boxes.[17] Millennium Park project manager Edward Uhlir said "Frank is just the cutting edge of the next century of architecture," and noted that no other architect was being sought.[15] Gehry was approached several times by Skidmore architect Adrian Smith on behalf of the city.[18] His hesitance and refusal to accept the commission was overcome by Cindy Pritzker, the philanthropist, who had developed a relationship with the architect when he won the Pritzker Prize in 1991. She enticed him in head on confrontations with a $15m funding commitment toward the bandshell's creation, according to John H. Bryan.[19] The choice of Gehry was a key component of having modern themes in the park.[15][18]

The initial construction of the park was under the auspices of the Chicago Department of Transportation because the project bridges the railroad tracks. However, as the project grew and expanded, its broad variety of amenities placed it under the jurisdiction of the city's Public Buildings Commission.[20]

In April 1999, the city announced that the Pritzker family had donated $15 million to fund Gehry's Bandshell and an additional nine donors committed $10 million.[21][22] The day of this announcement, Gehry agreed to the design request.[23] In November, when his design was unveiled, Gehry said the Bridge was preliminary and not well-conceived because funding for it was not committed.[24] The need to fund a bridge to span the eight-lane Columbus Drive was evident, but some planning for the park was delayed in anticipation of details on the redesign of Soldier Field.[25] In January 2000, the city announced plans to expand the park to include features that have become Cloud Gate, Crown Fountain, The McDonalds Cycle Center, and BP Pedestrian Bridge.[26] Later that month, Gehry unveiled his first design for the bridge, which included a winding bridge.[27]

Some sources say that the park was the outgrowth of the exuberance of private sponsors, and others say that Mayor Daley used his power to garner corporate supporters.[28] Bryan, the former Chief executive officer of Sara Lee Corporation, spearheaded the fundraising.[29] He says that sponsorship was by invitation and no one refused the opportunity to be a sponsor.[30] One Time magazine writer describes the park as the crowning achievement for Mayor Daley,[31] while another suggests the park's cost and time overages were examples of the city's mismanagement.[32] The July 16–18 opening gala was sponsored by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co.[33]

The community surrounding Millennium Park has become one of the most fashionable residential addresses in the city. In 2006, Forbes named 60602 as the hottest zip code in terms of price appreciation in the country,[34] with upscale buildings such as The Heritage at Millennium Park (130 N. Garland) leading the way for other buildings such as Waterview Tower, The Legacy and Joffrey Tower. The median sale price for residential real estate was $710,000 in 2005 according to Forbes, ranking it on the list of most expensive zip codes.[35] The park has been credited with increasing residential real estate values by $100/square foot.[36]

Features

Millennium Park is a portion of the larger Grant Park, the "front lawn" of downtown Chicago. One of the larger public parks in metropolitan Chicago, it is a showcase for postmodern architecture. It features the McCormick Tribune Ice Skating Rink, Peristyle at Wrigley Square, Joan W. and Irving B. Harris Theater for Music and Dance, AT&T Plaza, Chase Promenade and Trees in Millennium Park. The park is successful as a public art venue in part due to the grand scale of each piece and the open spaces for display.[37] There are four major artistic highlights: Cloud Gate, Crown Fountain, Lurie Garden and the Jay Pritzker Pavilion.[38] Millennium Park is often considered the largest roof garden in the world, having been constructed on top of a railroad yard and large parking garages. Of its 24.5 acres (99,000 m2) of land, Millennium Park contains 12.04 acres (48,700 m2) of permeable area. The park has a very rigorous cleaning schedule with many areas being swept, wiped down or cleaned multiple times a day.[39] The park is known for being user friendly.[40] Although the park was unveiled in July 2004, upgrades continued for some time afterwards.[41] Along with the cultural features above ground (described below) the park has its own 2218-space parking garage.[6]

Jay Pritzker Pavilion

The principal signature of Millennium Park is the Jay Pritzker Pavilion, a bandshell designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Frank Gehry with 4,000 fixed seats plus additional lawn seating for 7,000.[42] A Pritzker Architecture Prize honoree and National Medal of Arts winner, Gehry designed such landmarks as the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Der Neue Zollhof in Düsseldorf and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. Characteristic of Gehry, the Pritzker Pavilion consists of curving planes of stainless steel resembling the graceful blooming of a flower or the unfurling sails of a massive ship. The Pavilion was named after Jay Pritzker, whose family is known for owning Hyatt Hotels. The pavilion is Grant Park's small event outdoor performing arts venue, and complements Petrillo Music Shell, the park's older and larger bandshell. Pritzker Pavilion is built partially atop the Harris Theater for Music and Dance, the park's indoor performing arts venue, with which it shares a loading dock and backstage facilities.[43] The pavilion is seen as a major upgrade from the Petrillo Music Shell for those events it hosts.[29] Initially, the pavilion's lawn seats were free for all concerts, but this changed when Tori Amos performed the first rock concert there on August 31, 2005.[44]

The Pritzker Pavilion is the home of the Grant Park Symphony Orchestra and Chorus and the Grant Park Music Festival, the nation's only remaining free, municipally supported, outdoor, classical music series.[45] The Festival is presented by the Chicago Park District and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs.[46] The Pavilion also hosts a wide range of music series and annual performing arts events.[47][48][49] Performers ranging from mainstream rock bands to classical musicians and opera singers have appeared at the pavilion,[50] which even hosts physical fitness activities such as yoga.[51] All rehearsals at the pavilion are open to the public; trained guides are available for the music festival rehearsals, which are well-attended.[52]

The construction of the pavilion created a legal controversy, given that there are historic limitations on the height of buildings in Grant Park. To avoid these legal restrictions, the city classifies the bandshell as a work of art rather than a building.[53] With several design and assembly problems, the construction plans were revised over time, with features eliminated and others added as successful fundraising allowed the budget to grow.[26] In the end, the performance venue was designed with a large fixed seating area, a Great Lawn, a trellis network to support the sound system and a signature Gehry stainless steel headdress.[54] It features a sound system with an acoustic design that replicates an indoor concert hall sound experience.[55] The pavilion and Millennium Park have received recognition by critics, particularly for their accessibility; an accessibility award ceremony held at the pavilion in 2005 described it as "one of the most accessible parks – not just in the United States but possibly the world".[56]

AT&T Plaza and Cloud Gate

AT&T Plaza is a public space that hosts the Cloud Gate sculpture.[57] It was opened in the summer of 2004 with the initial unveiling of the sculpture during the grand opening weekend of the park. Ameritech Corporation/SBC Communications Inc. donated US$3 million for the naming right to the space.[26][58] Cloud Gate is a three-story, 110-ton steel sculpture that has been dubbed by residents as "The Bean" because of its bean-like shape. The sculpture is the work of world-renowned artist Anish Kapoor and is the first of his public art in the United States. The piece was privately funded at the cost of $23 million, which was considerably more than the original estimate of $6 million. The piece is wildly popular.[59][60]

The sculpture was selected during a design competition.[61] After Kapoor's design was chosen, numerous technological concerns regarding the design's construction and assembly arose,[62][63][64][65] in addition to concerns regarding the sculpture's upkeep and maintenance.[64][66] Various experts were consulted, some of whom believed the design could not be implemented.[67] Eventually, a feasible method was found, but the sculpture's construction fell behind schedule. It was unveiled in an incomplete form during the Millennium Park grand opening celebration in 2004,[68] before being concealed again while it was completed.[69][70] When Millennium Park opened in 2004, the grid of welds around each metal panel was still visible. In early 2005, workers polished out the seams.[71] Cloud Gate was formally dedicated on May 15, 2006,[60][72] and it has since gained considerable popularity, both domestically and internationally.[73][74][75][76][77]

Cloud Gate is a highly polished reflective steel sculpture that is inspired by liquid mercury and the sculpture's surface reflects and distorts the city's skyline.[61][78] The curved, mirror-like surface of the sculpture provides striking reflections of visitors,[73] the city skyline (particularly the historic Michigan Avenue "Streetwall") and the sky.[79][80] Visitors are able to walk around and under Cloud Gate's 12-foot (3.7 m) high arch. On the underside is the "omphalos" (Greek for "navel"), a concave chamber that warps and multiplies reflections. The sculpture builds upon many of Kapoor's artistic themes and is popular with tourists as a photo-taking opportunity for its unique reflective properties.[81][82]

The sculpture and AT&T Plaza are located on top of Park Grill, between the Chase Promenade and McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink. Made up of 168 stainless steel plates welded together, its highly polished exterior has no visible seams. It is Template:Ft to m and weighs 110 short tons (100 t; 98 long tons).[62] The plaza has become a place view the McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink and during the Christmas holiday season, the Plaza hosts Christmas caroling.[83]

Crown Fountain

Crown Fountain is a first of its kind interactive work of public art and video sculpture, named in honor of Chicago's Crown family and designed by Catalan conceptual artist Jaume Plensa, it opened in July 2004.[84][85] The fountain is composed of a black granite reflecting pool placed between a pair of transparent glass brick towers. The towers are Template:Ft to m tall,[84] and they use light-emitting diodes behind the bricks to display digital videos on their inward faces. Construction and design of the Crown Fountain cost $17 million.[86] Weather permitting, the water operates from May to October,[87] intermittently cascading down the two towers and spouting through a nozzle on each tower's front face. When the screens are illuminated they show the faces of nearly a thousand individual Chicagoans, which features the vast diversity of the city. Playing on the theme of historical fountains based around gargoyles with water coming through the open mouth of the creature, each video includes moments where the person purses his or her lips and water spouts from a point in the display, such that it appears that the person is spitting the water out. This happens roughly every five minutes, and there is also a continuous stream of water that cascades over the images.

Residents and critics have praised the fountain for its artistic and entertainment features.[88][89][90] It highlights Plensa's themes of dualism, light, and water, extending the use of video technology from his prior works.[91] Its use of water is unique among Chicago's many fountains, in that it promotes physical interaction between the public and the water. Both the fountain and Millennium Park are highly accessible because of their universal design.[56]

Crown Fountain has been the most controversial of all the Millennium Park features. Before it was even built, some were concerned that the sculpture's height violated the aesthetic tradition of the park.[92] After construction, surveillance cameras were installed atop the fountain, which led to a public outcry (and their quick removal).[93][94][95]

However, the fountain has survived its somewhat contentious beginnings to find its way into Chicago pop culture. It is a popular subject for photographers and a common gathering place. While some of the videos displayed are of scenery, most attention has focused on its video clips of local residents, in which almost a thousand Chicagoans randomly appear on two screens.[96] The fountain is a public play area and offers people an escape from summer heat, allowing children to frolic in the fountain's water.[97]

McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink and Park Grill

McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink is a multipurpose venue located along the western edge of Millennium Park in the Historic Michigan Boulevard District. On December 20, 2001, it became the first attraction in Millennium Park to open,[13][98] which was a few weeks ahead of the Millennium Park underground parking garage.[13] The $3.2 million plaza was funded by a donation from the McCormick Tribune Foundation.[99] For four months a year, it operates as McCormick Tribune Ice Rink, a free public outdoor ice skating rink.[100] It is generally open for skating from mid-November until mid-March and hosts over 100,000 skaters annually. It is known as one of Chicago's better outdoor people watching locations during the winter months.[101][102] It is operated by the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs rather than the Chicago Park District,[103][104] which operates most major public ice skating rinks in Chicago.[100]

For the rest of the year, it serves as The Plaza at Park Grill or Park Grill Plaza, Chicago's largest al fresco dining facility.[105] The 150-seat Park Grill hosts various culinary events and musical performances during its months of outdoor operation.[105][106] It briefly served as an open-air exhibition space. From June 21 to September 15, 2002, the Plaza hosted the inaugural exhibit in Millennium Park.[107]

It is affiliated with the 300-seat indoor Park Grill restaurant located beneath AT&T Plaza and Cloud Gate. The outdoor restaurant offers scenic views of the park. The Park Grill is the only full-service restaurant in Millennium Park. It regularly places among the leaders in citywide best-of competitions for best burger,[108][109][110][111][112] and it is widely praised for its views.[113][114][115][116] The restaurant has been controversial due to the numerous associates of Mayor Daley who are investors, its exclusive location and lucrative contract terms. One of the most financially successful restaurants in Chicago, the Park Grill remains exempt from property taxes after a multi-year litigation which reached the appellate courts in Illinois.[117][118][119]

BP Pedestrian Bridge

BP Pedestrian Bridge is a pedestrian bridge crossing Columbus Drive that spans it to connect Daley Bicentennial Plaza with Millennium Park, both parts of the larger Grant Park. The girder footbridge is the first bridge designed by Gehry, and was named for British Petroleum who donated $5 million to the construction of the Park.[120][121] It opened along with the rest of Millennium Park on July 16, 2004.[122] Gehry had been courted by the city to design the bridge and the neighboring Jay Pritzker Pavilion, and eventually agreed to do so after the Pritzker family funded the Pavilion.[18][123][124] The bridge is known for its aesthetics, and Gehry's style is seen in its biomorphic allusions and extensive sculptural use of stainless steel plates to express abstraction. The bridge is referred to as snakelike or serpentine in character due to its curving form.[125] The bridge's design enables it to bear a heavy load and is known for its aesthetics. Additionally, it serves acoustic needs as a sound barrier and functional needs as a connecting link between Millennium Park and points east.[125]

The pedestrian bridge serves as a noise barrier for traffic sounds from Columbus Drive. It is a connecting link between Millennium Park and destinations to the east, such as the nearby lakefront, other parts of Grant Park and a parking garage.[19] BP Bridge uses a concealed box girder design with a concrete base, and its deck is covered by hardwood floor boards.[126] It is designed without handrails, using stainless steel parapets instead.[125] The total length is 935 feet (285 m), with a five percent slope on its inclined surfaces that makes it barrier free and accessible.[127][128] It has won awards for its use of sheet metal.[129][130] Although the bridge is closed in winter because ice cannot be safely removed from its wooden walkway, it has received favorable reviews for its design and aesthetics.[131]

Harris Theater

The Joan W. and Irving B. Harris Theater for Music and Dance is a 1525-seat theater for the performing arts located along the northern edge of Millennium Park. Constructed in 2002–03, it is the city's premier performance venue for small and medium sized performance groups,[132] which had previously been without a permanent home and were underserved by the city's performing venue options. It is the first new performing arts venue built in the city's theater district or downtown since 1929.[133] The theater, which is largely underground due to Grant Park-related height restrictions, was named for its primary benefactors, Mr & Mrs. Irving Harris.[134] It serves as the Park's indoor performing venue, a compliment to Jay Pritzker Pavilion, which hosts the park's outdoor performances. Among the regularly featured local groups are Joffrey Ballet, Hubbard Street Dance Chicago and Chicago Opera Theater.[135] It provides subsidized rental, technical expertise, and marketing support for the companies using it,[136] and it turned a profit in its fourth fiscal year.[137]

The Harris Theater has hosted notable national and international performers, such as the New York City Ballet's first visit to Chicago in over 25 years (in 2006). The theater began offering subscription series of traveling performers in its 2008–09 fifth anniversary season.[138][139][140] Performances through this series have included the San Francisco Ballet,[141] Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Stephen Sondheim.[142]

The theater has been credited as contributing to the performing arts renaissance in Chicago,[143] and it has been favorably reviewed for its acoustics, sightlines, proscenium and for providing a home base for numerous performing organizations.[43][144][145] Although it is seen as a high caliber venue for its music audiences, the theater is regarded as less than ideal for jazz groups because it is more expensive and larger than most places where jazz is performed.[145] The design has been criticized for traffic flow problems, with an elevator bottleneck.[146][147] However, the theater's prominent location and its underground design to preserve Millennium Park have been praised.[43] Although there were complaints about high priced events in its early years, discounted ticket programs were introduced in the 2009–10 season.[148]

Wrigley Square

Wrigley Square is a public square located in the northwest section of Millennium Park in the Historic Michigan Boulevard District.[149] It contains the Millennium Monument, a nearly full-sized replica of the semicircle of paired Greek Doric-style columns (called a peristyle) that originally sat in this area of Grant Park, near East Randolph Street and North Michigan Avenue, between 1917 and 1953.[149] The square also contains a large lawn and a public fountain.

McDonald's Cycle Center

McDonald's Cycle Center is a 300-space heated and air conditioned indoor bike station located in the northeast corner of Millennium Park. The facility provides lockers, showers, a snack bar with outdoor summer seating, bike repair, bike rental, 300 bicycle parking spaces and other amenities for downtown bicycle commuters and utility cyclists. The Bike Station also accommodates runners and in-line skaters.[150][151][152] In addition, the station provides space for a Chicago Police Department Bike Patrol Group.[153] The city-built center opened in July 2004. Since June 2006, it has been sponsored by McDonald's and several other partners, including city departments and bicycle advocacy organizations.[152][154] The Cycle Center is accessible by membership and day pass.[155]

Planning for the Cycle Center was part of the larger "Bike 2010 Plan", in which the city aimed to make itself more accommodating to bicycle commuters. This plan (now replaced by the "Bike 2015 Plan")[156] included provisions for front-mounted two-bike carriers on Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) buses, permitting bikes to be carried on Chicago 'L' trains, installing numerous bike racks and creating bicycle lanes in streets throughout the city.[157] Additionally, the Chicago metropolitan area's other mass transit providers, Metra and Pace, have developed increased bike accessibility.[158] Mayor Daley was an advocate of the plan, noting it is also an environmentally friendly effort to cut down on traffic.[157][159] Suburban Chicago-based McDonald's sponsorship of the Cycle Center fit in well with its efforts to help its customers become more healthy by encouraging "balanced, active lifestyles".[160]

Environmentalists, urban planners and cycling enthusiasts around the world have expressed interest in the Cycle Center, and want to emulate what they see as a success story in urban planning and transit-oriented development.[154][161][162][163] Pro-cycling and environmentalist journalists in publications well beyond the Chicago metropolitan area have described the Cycle Center as exemplary, impressive, unique and ground-breaking.[154][161]

Lurie Garden

Lurie Garden is a 2.5-acre (10,000 m2) public garden located at the southern end of Millennium Park designed by Kathryn Gustafson, Piet Oudolf, and Robert Israel that opened on July 16, 2004.[164] The garden is a combination of perennials, bulbs, grasses, shrubs and trees.[165] It is the featured nature component of the world's largest green roof. The garden cost $13.2 million and has a $10 million financial endowment for maintenance and upkeep.[38][166] It was named after Ann Lurie.[167] The garden is a tribute to the city whose motto is "Urbs in Horto," which is a Latin phrase meaning City in a Garden.[164] The Garden is composed of two "plates". The dark plate depicts Chicago's history by presenting shade-loving plant material. The dark plate has a combination of trees that will provide a shade canopy for these plants when they fill in. The light plate, which includes no trees, represents the city's future with sun-loving perennials that thrive in the heat and the sun.[87]

Exelon Pavilions

The Exelon Pavilions are a set of four solar energy generating structures in Millennium Park. The pavilions provide sufficient energy to power the equivalent of 14 star-rated energy-efficient houses in Chicago.[168] The Pavilions were designed in January 2001 and construction began in January 2004. The Southeast Exelon Pavilion and Southwest Exelon Pavilion (jointly the South Exelon Pavilions) along Madison Street were completed and opened in July 2004 and the Northeast Exelon Pavilion and Northwest Exelon Pavilion (jointly the North Exelon Pavilions) along Randolph Street were completed in November 2004, with a grand opening on April 30, 2005.[169] Besides producing energy, three of the four pavilions provide access to the park's below ground parking garages and the fourth serves as the park's welcoming center.[168] Exelon, a company that generates the electricity transmitted by its subsidiary Commonwealth Edison,[170] donated approximately $6 million for the Pavilions.[171]

Boeing Galleries

Boeing Galleries are a pair of outdoor exhibition spaces within Millennium Park located along the south and north mid-level terraces, above and east of Wrigley Square and the Crown Fountain.[172] The spaces are located along the south and north mid-level terraces, above and east of Wrigley Square and the Crown Fountain.[172] In a conference at the Chicago Cultural Center, Boeing President and Chief Executive Officer James Bell to Mayor Daley announced Boeing would make a $5 million grant to fund both the construction of and an endowment for the space.[172] The space has hosted grand scale art exhibits some of which have run for two full summers.

Chase Promenade

Chase Promenade is an open-air tree-lined pedestrian walkway in Millennium Park that opened July 16, 2004. The Promenade was made possible by a gift from the Bank One Foundation.[173] Its 8 acres (32,000 m2) accommodate exhibitions, festivals and other family events.[173] It also serves as a venue for event planning on a rental basis.[174] The Chase Promenade hosted the 2009 Pavilion projects, which were the cornerstone of the citywide Burnham Plan centennial celebration.[175]

Nichols Bridgeway

The Nichols Bridgeway is a pedestrian bridge that opened on May 16, 2009 and that connects the South end of the Millennium Park with the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago. It begins at the south west end of the Great Lawn and extends across Monroe Street connecting to the third floor of the West Pavilion of the Art Institute of Chicago.[176][177]

Designed by Renzo Piano, the architect of the Modern Wing, the bridge is approximately 620 ft (190 m) long and 15 ft (4.6 m) wide. The bottom of the Bridgeway is made of white, painted structural steel, the floor is made of aluminum planking and the 42" tall railings are steel set atop stainless steel mesh. The Bridgeway features anti-slip walkways and heating elements to prevent the formation of ice and meets ADA standards for universal accessibility. The bridge is named after museum donors Alexandra and John Nichols.[178] The bridge design was inspired by the hull of a boat.[179]

2009 Pavilion projects

The pavilions by Zaha Hadid and Ben van Berkel, which were located in the Chase Promenade South, were constructed to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago. They were privately funded[180][181] and were designed to be temporary structures.[182] The pavilions served as the focal point of Chicago's year-long celebration while they symbolize the city's continued pursuit of the Plan's architectural vision with contemporary architecture and planning.[183]

The van Berkel Pavilion is composed of two parallel rectangular planes joined by curving scoops[184] on a steel frame with glossy white plywood covering it. It is situated on a raised platform which is sliced by a ramp entrance making it ADA accessible.[185] The Hadid Pavilion is a tensioned fabric shell fitted over a curving aluminum framework exceeding 7,000 pieces. It accommodated centennial-themed, video presentation its interior fabric walls.[186]

Both Pavilions were scheduled to be unveiled on June 19, 2009. However, the Pavilion by Hadid endured construction delays and a construction team change, which led to nationwide coverage of the delay in publications such as The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.[183][187] Only its skeleton was availed to the public on the scheduled date, and the work was completed and unveiled on August 4, 2009. The van Berkel pavilion endured a temporary closure due to unanticipated wear and tear from August 10–14.[188]

Budget

During development and construction of the park, many structures were added, redesigned or modified. These changes often resulted in budget increases. For example, the band shell's proposed budget was $10.8 million. When the elaborate, cantilevered Gehry design required extra piling be driven into the bedrock to support the added weight, the cost of the band shell eventually spiraled to $60.3 million. The cost of the park, as itemized in the following table, amounted to almost $500 million.[189] According to Lois Weisberg, Commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs and James Law, Executive director of Mayor's Office of Special Events, once the full scope of the project was finalized the project was completed within the revised budget.[190]

| Project | Proposed cost | Final cost | % of proposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garage | $87.5 million | $105.6 million | 121% |

| Metra superstructure | $43.0 million | $60.6 million | 141% |

| Jay Pritzker Pavilion | $10.8 million | $60.3 million | 558% |

| Harris Theater | $20.0 million | $60.0 million | 300% |

| Park finishes/landscaping | N/A | $42.9 million | |

| Design and management costs | N/A | $39.5 million | |

| Endowment | $10.0 million | $25.0 million | 250% |

| Crown Fountain | $15.0 million | $17.0 million | 113% |

| BP Pedestrian Bridge | $8.0 million | $14.5 million | 181% |

| Lurie Garden | $4.0–8.0 million | $13.2 million | 330%–165% |

| Cloud Gate sculpture | $6.0 million | $23.0 million | 383% |

| Exelon Pavilions | N/A | $7.0 million | |

| Peristyle/Wrigley Square | $5.0 million | $5.0 million | 100% |

| Chase Promenade | $6.0 million | $4.0 million | 67% |

| McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink | $5.0 million | $3.2 million | 64% |

| Misc. (fencing, terraces, graphics) | N/A | $1.6 million |

Criticism and controversy

The Millennium Park project has been the subject of some criticism since its inception. In addition to concerns about the cost overrun, individuals and organizations have complained that the money spent on the park might have gone to other worthy causes, specifically citing ongoing issues with poverty in Chicago and problems within the city's schools.

In 1836, a year before Chicago was incorporated,[191] the Board of Canal Commissioners held public auctions for the city's first lots. Foresighted citizens, who wanted the lakefront kept as public open space, convinced the commissioners to designate the land east of Michigan Avenue between Randolph Street and Park Row (11th Street) "Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction, whatever."[192] Grant Park has been "forever open, clear and free" since, protected by legislation that has been affirmed by four previous Illinois Supreme Court rulings.[193][194][195][196] In 1839, United States Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett declared the land between Randolph Street and Madison Street east of Michigan Avenue "Public Ground forever to remain vacant of buildings".[191] Aaron Montgomery Ward, who is known both as the inventor of mail order and the protector of Grant Park, twice sued the city of Chicago to force it to remove buildings and structures from Grant Park and to keep it from building new ones.[197][198] In 1890, arguing that Michigan Avenue property owners held easements on the park land, Ward commenced legal actions to keep the park free of new buildings. In 1900, the Illinois Supreme Court concluded that all landfill east of Michigan Avenue was subject to dedications and easements.[199] In 1909, when Ward sought to prevent the construction of the Field Museum of Natural History in the center of the park, the courts affirmed his arguments.[200][201] As a result, the city has what are termed the Montgomery Ward height restrictions on buildings and structures in Grant Park. However, Crown Fountain and the 139-foot (42 m) Pritzker Pavilion were exempt from the height restriction because they were classified as works of art and not buildings or structures.[202] Some say the Pavilion is described as a work of art to dodge the protections established by Ward who is said to continue to rule and protect Grant Park from his grave.[53] This is why Harris Theater is largely underground,[202] while the adjacent Pritzker Pavilion is described as a work of art to dodge the height restriction.[53] Crown Fountain, which has been described as having a height stemming from a "pissing contest" with other park feature artists,[92] was also exempted from the height restriction as a work of art.[202]

Although the park's design and architectural elements have won wide praise, there has been some criticism of its aesthetics. Other criticism has revolved around the larger issue of corruption and political favoritism in the city; for example a July 2004 New York Times article reported that an inflated contract for park cleanup had gone to a company that made large contributions to Mayor Daley's election campaign.[3] The park's only full service restaurant, Park Grill, has numerous friends of the Mayor.[203][204]

Concerns have also been raised over the use of mixed taxpayer and corporate funding and associated naming rights for sections of the park. While a large monument in the northwest corner of the park honors the many private and corporate donors who contributed to its construction, entire squares and plazas within the park are named for their corporate underwriters, with the sponsors' names prominently indicated with stone markers (Boeing Gallery, Exelon Pavilion, AT&T Plaza, Wrigley Square); some critics have deemed this to be inappropriate for a public space. The naming of the McDonald's Cycle Center for the local company was one of several naming controversies. Longtime writer for the Chicago Tribune and current Tribune health and fitness reporter, Julie Deardorff, described the move as a continuation of the '"McDonaldization" of America' and as somewhat "insidious" because the company is making itself more prominent as the social sentiment is to move away from fast food.[160] Timothy Gilfoyle, author of Millennium Park: Creating a Chicago Landmark, notes that a controversy surrounds the "tasteless" corporate naming of several of the Park's features, including the bridge, which was named after an oil company.[205] It is well-documented that naming rights were sold for high fees,[206] and Gilfoyle was not the only one who chastised park officials for selling naming rights to the highest bidder. Public interest groups have crusaded against commercialization of Chicago parks.[207] However, many of the donors have a long history of local philanthropy and the funds were essential to providing necessary financing for several features of the park.[14]

Costs associated with events at both the Harris Theater and Pritzker Pavilion have been controversial. However, Chicago Tribune journalist, John von Rhein, notes that the theater's size poses a challenge to the performers attempting to fill its seats, and feels that it overemphasizes high-priced events.[208] In 2009–10, the theater introduced a pair of discounted ticket programs:[148] a $5 lunchtime series of 45-minute dance performances,[209] and a discounted $10 ticket program was initiated for in-person, cash-only purchases in the last 90 minutes before performances.[148] Once the pavilion was built, the initial plan was that the lawn seating would be free for all events. An early brochure for the Grant Park Music Festival said "You never need a ticket to attend a concert! The lawn and the general seating section are always admission free."[44] However, when parking revenue fell short of estimates during the first year, the city charged $10 for lawn seating at the August 31, 2005, concert by Tori Amos.[44] Amos, a classically trained musician who chose only piano and organ accompaniment for her concert, earned positive reviews as the inaugural rock and roll performer in a venue that regularly hosts classical music.[48][49] The city justified the charge by contending that since the Pavilion is an open air venue, there were many places in Millennium Park, such as the Cloud Gate, Crown Fountain and Lurie Gardens, where one could have enjoyed the sounds or the atmosphere of the park without having to pay.[44][210][211]

When the park first opened in 2004, Metra police stopped a Columbia College Chicago journalism student, working on a photography project in Millennium Park, and his film confiscated because of fears of terrorism.[212] In 2005, the sculpture attracted some controversy when a professional photographer without a paid permit was denied access to the piece.[213] As is the case for all works of art currently covered by United States copyright law, the artist holds the copyright for the sculpture. This allows the public to freely photograph Cloud Gate, but permission from Kapoor or the City of Chicago (which has licensed the art) is required for any commercial reproductions of the photographs. The city first set a policy of collecting permit fees for photographs. These permits were initially set at $350 per day for professional still photographers, $1,200 per day for professional videographers and $50 per hour for wedding photographers. The policy has been changed so permits are only required for large-scale film, video and photography requiring ten-man crews and equipment.[214]

In November 2006, Crown Fountain became the focus of a public controversy when the city added surveillance cameras atop each tower. Purchased through a $52 million Department of Homeland Security grant to the Chicago area, the cameras were part of a surveillance system augmenting eight other cameras covering all of Millennium Park.[93] The city claimed the cameras, similar to those used throughout the city at high-crime areas and traffic intersections, were intended to remain on the towers for several months until permanent, less intrusive replacements were secured.[94] City officials had consulted the architects who collaborated with Plensa on the tower designs, but Plensa himself had not been notified.[95] Public reaction was negative, as bloggers and the artistic community decried the cameras on the towers as inappropriate and a blight.[94][95] The city contended that the cameras were largely for security reasons, but also partly to help park officials monitor burnt-out lights.[95] The Chicago Tribune quickly published an article concerning the cameras as well as the public reaction, and the cameras were removed the next day. Plensa supported their removal.[94]

The park curfew (the park is closed from 11 p.m. to 6 a.m. daily)[215] and obvious presence of security guards is also cited in some quarters as working against a public park. For example, during the dusk to dawn event Looptopia on May 11 and May 12, 2007, public access to the park was prevented by police enforcement of the park curfew.

In both 2005 and 2006, almost the entire Millennium Park was closed for a day for corporate events. This was controversial for both commuters who walk through the park and for tourists who were lured by the attractions of the public park.[216] On September 8, 2005, Toyota Motor Sales USA paid $800,000 to rent all venues in the park except Wrigley Square, Lurie Garden, McDonald's Cycle Center and Crown Fountain from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.[216][217] The money was used to both fund free events in the park such as concerts and for day-to-day operations.[217] The events included the Lurie Garden Festival, a Steppenwolf Theater production, musical performers along the Chase Promenade all summer long, a jazz series, children's concerts and other free events.[218] Toyota, as a sponsor, also had its name included on Millennium Park brochures, the park's Web site, and park advertising signage.[217] Since this had been announced in May this closure provided a public relations opportunity for General Motors who shuttled some 1500 tourists to see other Chicago attractions.[216] From Toyota's perspective the $300,000 was a rental expense and the $500,000 was a sponsoring donation. On August 7, 2006, Allstate paid a $200,000 rental expense and a similar $500,000 sponsoring donation. For this price, Allstate acquired the visitation rights to a different set of features and only had exclusive access to certain features after 4 p.m.[219]

Chicago is a dog-friendly city with a half dozen dog beaches.[220] Yet, the city does not permit dogs in the park in general. However, dogs on duty to serve the disabled or visually impaired are permitted.[87]

Recognition

The Financial Times describes the park as an extraordinary 21st century park resulting from a unique combination of money and power that liberates artistic expression in the way it creates a new iconic images of the city.[19] Time magazine views both the Cloud Gate and the Jay Pritzker Pavilion as part of a well-planned visit to Chicago.[221] Frommer's lists exploring Millennium Park as one of the four best free things to do in the city,[222] and it commends the park for it various artistic offerings.[223] Lonely Planet recommends an hour long stroll to see the park's playful art.[224] The park is praised as a "showcase of art and urban design" by the San Francisco Chronicle.[225] Time refers to it as an artful arrangement resulting from a creative ensemble.[226] The park is considered to be beyond the ambitions of many cities.[227] The park is discussed in the book 1,000 Places to See in the U.S.A. & Canada Before You Die, which describes Millennium Park as a renowned attraction.[228]

"This is not simply a background park, where a series of individual objects exist in a field. The objects here have become the field. It is densely packed like the city itself. This is a different idea of an exterior experience than in most parks. It is closer to a theme park or a shopping mall."

—Richard Solomon, Director of Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts[19]

A book entitled Millennium Park: Creating a Chicago Landmark by Timothy J. Gilfoyle was a New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice in 2006.[229] The book was also an editor's choice for the San Francisco Chronicle.[230]

The park was designed so that it only needs a single lift and its accessibility has won its project director the 2005 Barrier-Free America Award in recognition of individual leadership in making our country more accessible for all Americans.[231] In addition, the park was recognized in the Green Roof Awards of Excellence in the Intensive Industrial/Commercial category.[232] Green Roof considers the park to be the largest green roof in the world, as it covers a structural deck supported by two reinforced concrete cast-in-place garages and steel structures that span over Illinois Central Railroad tracks.[233][234] McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink and Jay Pritzker Pavilion both provide accessible restrooms.[87] The park opened with 78 women's toilet fixtures and 45 for men with heated ones on the east side of Pritzker Pavilion. It also had about six dozen park benches designed by Kathryn Gustafson (the landscape architect responsible for Lurie Gardens).[235]

In addition to formal critical review, the park is admired as an example of successful urban planning by other mayors such as San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, who wishes San Francisco could do the same thing.[236][237] Even the Mayor of Shanghai has enjoyed himself at the park.[238]

Popular culture

Jeff Garlin claims that I Want Someone to Eat Cheese With was the first Hollywood movie to incorporate Millennium Park.[239] The film was not released until after several other movies such as The Weather Man starring Nicolas Cage, which was shot in part at the park's McCormick Tribune Plaza & Ice Rink.[240] The Break-Up shot scenes in the park and had to reshoot some of them because Cloud Gate was under cover in some of the initial shootings.[241] Butterfly on a Wheel shot some scenes in the park.[242] The Lake House also shot scenes in the park.[243] Leverage has filmed in the park.[244] Derailed is another movie that has filmed in the park.[245] The first few episodes of the first season of Prison Break featured shots of the fountain.[246]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Crain's List Lartgest Tourist Attractions (Sightseeing): Ranked by 2007 attendance". Crain's Chicago Business. Crain Communications Inc. June 23, 2008. p. 22.

- ^ Ryan, Karen (April 12, 2005). "Chicago's New Millennium Park Wins Travel & Leisure Design Award For "Best Public Space", And The American Public Works Association "Project Of The Year" Award" (PDF). City of Chicago. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Kinzer, Stephen (July 13, 2004). "Letter From Chicago; A Prized Project, a Mayor and Persistent Criticism". The New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ Daniel, Caroline and Jeremy Grant (September 10, 2005). "Classical city soars above Capone clichés". The Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd. Archived from the original on June 24, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Laurie and Liam Ford (July 18, 2004). "$16 million in lawsuits ensnare pavilion at Millennium Park". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "A no place transformed into a grand space – What was once a gritty, blighted site is now home to a glistening, cultural spectacle that delivers joy to its visitors". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ Nance, Kevin (May 23, 2005). "Snakelike walkway by Gehry dedicated at Millennium Park". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Michael J. (August 6, 2006). "No Headline". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (August 6, 2006). "Millennium Park". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b "Untitled (Baseball Park Codes)". retrosheet.org.

- ^ "Park History". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Kamin, Blair (March 18, 1999). "Will Too Many Architects Spoil Grant Park's Redesign?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Mayor Daley, McCormick Tribune Executives Cut Ribbon on Spectacular Skating Rink at Millennium Park" (PDF). Millennium Park News. Public Building Commission of Chicago. Winter 2001–2002. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ a b Smith, Sid (July 15, 2004). "Sponsors put money where their names are". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c Bey, Lee (February 18, 1999). "Building for future – Modern architect sought for park". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ "The City". Daily Herald. February 18, 1999. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Warren, Ellen and Teresa Wiltz (February 17, 1999). "City Has Designs On Ace Architect For Its Band Shell". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c Kamin, Blair (April 18, 1999). "A World-Class Designer Turns His Eye To Architecture's First City". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Daniel, Caroline (July 20, 2004). "How a steel bean gave Chicago fresh pride". The Financial Times.

- ^ "Following the Money for Millennium Park". Neighborhood Capital Budget Group. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ "Millennium Park Gets Millions". Chicago Tribune. April 27, 1999. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (April 28, 1999). "Room for Grant Park to grow". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ De LaFuente, Della (April 28, 1999). "Architect on board to help build bridge to 21st century". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (November 4, 1999). "Architect's Band Shell Design Filled With Heavy-Metal Twists". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (November 23, 1999). "Timing Crucial Plotting Grant Park's Future". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c Song, Lisa (January 7, 2000). "City Tweaks Millennium Park Design". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Donato, Marla (January 28, 2000). "Defiant Architect Back With Revised Grant Park Bridge Design". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Thigpen, David (April 18, 2005). "Richard the Second". Time. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Magnificent Millennium". Chicago Tribune. July 15, 2004. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Sid (July 15, 2004). "Sponsors put money where their names are". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ Cole, Wendy (January 22, 2007). "In Chicago, t-he Dynasty Rolls On". Time. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ Isackson, Noah (December 17, 2004). "Creative Thinking In Chicago". Time. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ Ford, Liam (May 21, 2004). "City park has friend to bank on". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ "Zip Codes With Greatest Appreciation". forbes.com. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "#404 60602". forbes.com. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ Sharoff, Robert (June 4, 2006). "How a Park Changed a Chicago Neighborhood". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 344.

- ^ a b Freemen, Allen (2004). "Fair Game on Lake Michigan". Landscape Architecture Magazine. American Society of Landscape Architects. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Spielman, Fran (December 16, 2005). "New amenities for Millennium Park?: Company proposes baby strollers, Disney training for workers". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "New city jewel invites us downtown to play". Chicago Sun-Times. July 16, 2004. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Dardick, Hal (January 10, 2005). "Park reflects vision still in its infancy – Upgrades for Millennium site are in the works, with more on way". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ "Facts and Dimensions of Jay Pritzker Pavilion". City of Chicago. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "Joan W. and Irving B. Harris Theater for Music and Dance – ** – 205 E. Randolph Drive – Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge, Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Herrmann, Andrew (September 1, 2005). "Howls over charge for Millennium Park concert // Watchdog contends lawn seats supposed to be free". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Macaluso, p. viii

- ^ GPMF2006 "Grant Park Music Festival". Grant Park Music Festival. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Calendar of Millennium Park Free Programs: Jazz". City of Chicago. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ a b Orloff, Brian (September 2, 2005). "Amos creates musical magic as Pritzker's first rock act". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ a b Elder, Robert K. (September 2, 2005). "Church of Tori holds a revival in heart of city". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Macaluso, p. 182

- ^ "Calendar of Millennium Park Free Programs: Fitness". City of Chicago. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ Macaluso, p. 216

- ^ a b c "In a fight over Grant Park, Chicago's mayor faces a small revolt" (subscription required). The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. October 4, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Sharoff, p. 24

- ^ Delacoma, Wayne. "The Jay Pritzker Music Pavilion Sounds as Good as it Looks". LARES Associates. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Deyer, Joshua (2005). "Chicago's New Class Act" (PDF). PN. Paralyzed Veterans of America. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Millennium Park News" (PDF). Public Building Commission of Chicago. Winter 2001–02. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ "Dawn of the Millennium". RedEye. July 16, 2004. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (June 5, 2008). "Anish Kapoor: Past, Present, Future". Time. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Carlson, Prescott. "Chicago's Millennium Park". Chicago Travel. About.com. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ a b Sharoff, p. 61

- ^ a b Gilfoyle, p. 165.

- ^ Schulze, Franz. "Sunday afternoon in the Cyber-Age Park: the city's new greensward features Frank Gehny's latest, plus "interactive" sculptural works by Jaume Plensa and Anish Kapoor". Art in America. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Steele, Jeffrey. "Special Project – Chicago's Millennium Park Project". McGraw-Hill Construction. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ Sharoff, p. 55.

- ^ Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen S. (May 16, 2006). "Bean's gleam has creator beaming – Artist Anish Kapoor admits being surprised by aspects of `Cloud Gate' at Monday's dedication ceremony in Millennium Park". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 202.

- ^ "Cloud Gate". Chicago Architecture Info. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Nunn, Emily (August 24, 2005). "Making it shine". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ "A place to reflect in Chicago". Los Angeles Times. January 2, 2005. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Ryan, Karen (August 18, 2005). "Cloud Gate Sculpture in Millennium Park to be Completely Untented by Sunday, August 28" (PDF). Millennium Park. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "The Bean Unveiled". Chicago Tonight. May 15, 2006. WTTW.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Lacayo, Richard (June 5, 2008). "Anish Kapoor: Past, Present, Future". Time. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ^ Kennedy, Randy (May 25, 2008). "The Week Ahead: May 25–31". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (July 13, 2004). "Letter From Chicago; A Prized Project, a Mayor and Persistent Criticism". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "What have artists wrought from 9/11?". USA Today. September 3, 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (December 18, 2004). "The Best Architecture". Time. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ Daniel, Caroline and Jeremy Grant (September 10, 2005). "Classical city soars above Capone clichés". The Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd. Retrieved July 31, 2008. (registration required for entire article)

- ^ Sharoff, p. 45

- ^ Jodidio, pp. 120–122

- ^ Baume, p. 18

- ^ Baume, p. 26

- ^ "Head downtown to catch Christmas spirit". Northwest Herald. November 21, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- ^ a b "Artropolis". Merchandise Mart Properties, Inc. 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ^ "Crown Fountain". Archi•Tech. Stamats Business Media. 2005. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Chicago's stunning Crown Fountain uses LED lights and displays". LEDs Magazine. PennWell Corporation. 2005. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Frequently Asked Questions". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "Crown Fountain—***1/2*—Monroe Drive and Michigan Avenue—Jaume Plensa, Barcelona with Krueck & Sexton Architects, Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Nance, Kevin (July 12, 2004). "Walking on the water—Artist Jaume Plensa reinvents the fountain for the 21st century". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ King, John (July 30, 2006). "Chicago's architectural razzmatazz: New or old, skyscrapers reflect city's brash and playful character". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 288.

- ^ a b Gilfoyle, pp. 290–291.

- ^ a b Janega, James (December 20, 2006). "Artworks stand alone as cameras lose perch". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Sander, Libby (December 28, 2006). "A Tempest When Art Became Surveillance". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Janega, James (December 19, 2006). "Now the Giant Faces Really are Watching". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Nance, Kevin (June 24, 2007). "Have you seen this face?; Many have yet to see their own images". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer (July 18, 2006). "Nation Sweats as Heat Hits Triple Digits". The New York Times. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ Satler, p. 170

- ^ "Art & Architecture: McCormick Tribune Plaza and Ice Rink". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ a b "Come Out and Skate". Chicago Park District. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ Davey, Monica (January 18, 2008). "Winter Day Out in Chicago". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ Davey, Monica (January 18, 2008). "5 Big Cities, 1 Winter Day (Slideshow)". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ "The McCormick Tribune Ice Rink in Millennium Park Opens for the 2007–08 Season on Wednesday, November 14" (PDF). Chicago Department of Public Affairs. October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us". Millennium Park. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Your Outdoor Table". parkgrillchicago.com. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ "Park Grill Events & Activities". parkgrillchicago.com. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ "Metro". Chicago Tribune. June 19, 2002. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ Vettel, Phil (June 14, 2005). "Metromix Chicago: Chicago's best burgers". chicago.metromix.com. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Chicagoist: The Way They Make You Feel: Trib Ranks Best Burgers". Chicagoist. June 14, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Student Guide: Best Burgers". Time Out Chicago. September 12, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Graham Meyer & Jennifer Tanaka, ed. (August 2008). "Best of Chicago". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ "Best Chicago Hamburgers 2008". Citysearch. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ "Zagat Buzz: Chicago Edition. "Do It Outdoors."". zagat.com. April 24, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ editorial staff. "Resto 100: Chicago's Essential Restaurants". New City Chicago. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

{{cite magazine}}: Text "date March 1, 2005" ignored (help) - ^ Simmons, Daniel, ed. (2006). 2006/07 Chicago Restaurants. Zagats Survey. ISBN 1-57006-801-1.

- ^ Lynn, Allison, ed. (2008). 08/09 Chicago Restaurants. Zagats Survey. ISBN 1-57006-981-6.

- ^ Joravsky, Ben (July 16, 2009). "Still No Property Tax Bill for the Park Grill: The restaurant under the Bean wins another round in its fight to avoid paying up like everybody else". Chicago Reader. Retrieved Mar 15, 2010.

- ^ Rhodes, Steve (July 28, 2009). "Clout Cafe Wins Again". NBC Chicago. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

{{cite news}}: External link in|work= - ^ Schroedter, Andrew (June 29, 2009). "Park Grill not required to pay property taxes: ruling". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

{{cite news}}: External link in|work= - ^ "BP Pedestrian Bridge". Glass, Steel and Stone. Artefaqs Corporation. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Laurie (July 2, 2001). "Band shell cost heads skyward – Millennium Park's new concert venue may top $40 million". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Category: Intensive Industrial/Commercial". Green Roofs for Healthy Cities. 2005. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (April 28, 1999). "Room for Grant Park to grow". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ De LaFuente, Della (April 28, 1999). "Architect on board to help build bridge to 21st century". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "BP Bridge- **** – Crossing Columbus Drive – Frank Gehry, Los Angeles". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Gilfoyle, pp. 196–201.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (June 23, 2000). "Gehry's Design: A Bridge Too Far Out?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: BP Bridge". City of Chicago. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ "Form And Function Come Together To Create A Pedestrian Bridge For Chicago: Millennium Park BP Pedestrian Bridge, Chicago, Ill". Architectural Metal Expertise. SMILMCF. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ "Millennium Park – BP Pedestrian Bridge". Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ Deyer, Joshua (2005). "Chicago's New Class Act" (PDF). PN. Paralyzed Veterans of America. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Art & Architecture: Joan W. and Irving B. Harris Theater for Music and Dance". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ "History of the Harris Theater". Harris Theater for Music and Dance at Millennium Park. 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "I. B. Harris, 94, Philanthropist and Executive, Dies". The New York Times. September 28, 2004. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth Canning. Frommer's Chicago 2010. Frommer's. pp. 251–252. ISBN 0470504684. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "Abouth Harris Theater: Mission". Harris Theater for Music and Dance at Millennium Park. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Harris Theater by the numbers". Chicago Tribune. September 14, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ^ von Rhein, John. "Harris Unveils Biggest Subscription Series Yet" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Harris Theater For Music And Dance Announces A World-Class 5th Anniversary Season Featuring The First-Ever Harris Theater Presents Series Of Chicago Premieres, Artistic Collaborations And A Line-up Of Some Of The World's Notable Artists Working Today" (PDF). harristheaterchicago.org. April 2, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Robinson, Regina (April 27, 2006). "Charter One Pavilion ups cool factor with VIP offer". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ "San Francisco Ballet—America's Oldest Professional Ballet Company—Embarks on a Four-city American Tour as Part of Its Year-long 75th Anniversary Celebration". San Francisco Ballet. June 10, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ von Rhein, John (May 6, 2009). "A starry Harris Theater lineup on tap for '09–'10". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Chris (November 9, 2008). "Chicago theater groups need own homes—and identities: Economy woes limit new building options for many arts entities". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ Delacoma, Wynne (January 26, 2005). "Glover finds right balance for Mozart". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 50. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Reich, Howard (September 14, 2008). "Expansive site, costs make for an imperfect fit". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Chris (September 14, 2008). "The rise of the Harris Theater: At age 5, the Millennium Park venue has become a pivotal part of Chicago's cultural landscape with a slate of programming to rival any single-venue arts center in the nation". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ^ Storch, Charles (September 14, 2008). "The Finances: With a good bottom line, a look toward the future: Harris Theater At 5". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Chicago's Harris Theater to Welcome Baryshnikov, Battle and Lang Lang in 2009–2010". Playbill. August 19, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Art & Architecture: Wrigley Square and Millennium Monument (Peristyle)". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ "Daley Opens New Millennium Park Bicycle Station". City of Chicago. July 19, 2004. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ Livingston, Heather (March 2005). "Millennium Park Bike Station Offers Viable Commuting Option". AIArchitect. The American Institute of Architects. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b "Art & Architecture: McDonald's Cycle Center". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "Bicycle Station – *** – Near Randolph and Columbus Drives – Muller & Muller, Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c Brettman, Allan (June 23, 2005). "Official Recruits Portland To Build Bike Center". The Oregonian. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ George, Doug (April 29, 2005). "Get in gear! – It's bike season, and we take you on a monthlong tour of the best cycling activities". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ^ "Bike 2015 Plan". City of Chicago. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Washburn, Gary (June 13, 2003). "Bike depot plan may turn commute into easy ride". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "Local Digest". Daily Southtown. October 24, 2005. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "McDonald's to sponsor bicycle center". Chicago Sun-Times. June 10, 2006. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Deardorff, Julie (June 18, 2006). "If McDonald's is serious, menu needs a makeover". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Kalinowski, Tess (June 1, 2007). "Bike station in Windy City should show T.O. the way – Chicago's Cycle Center offers parking, showers; similar plan envisioned for Toronto's downtown". Toronto Star. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ Barrett, Peter (May 25, 2007). "Would it work (here?)". The Age. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ Krcmar, Steven (September 19, 2004). "Bicyclists Feel Left Out In The Cold – Bikers Put Out After T Moves Racks Outdoors". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "Art & Architecture: Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Herrmann, Andrew (July 15, 2004). "Sun-Times Insight". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Raver, Anne (July 15, 2004). "Nature; Softening a City With Grit and Grass". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b "Art & Architecture: Exelon Pavilions: Millennium Park Welcome Center and Garage Entrances". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: Exelon Pavilions Facts and Figures". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "Exelon Pavilions". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ Herrmann, Andrew (July 15, 2004). "Sun-Times Insight". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 16.

- ^ a b c "Boeing to Fund Open-air Gallery Spaces in Chicago's Millennium Park". Boeing. March 16, 2005. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ^ a b "Art & Architecture: Chase Promenade". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ "Private Rentals: Photo Galleries: Chase Promenade". City of Chicago. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (June 24, 2008). "Footnotes". The New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Weiss, Hedy (May 10, 2009). "Growing in style – Art Institute's Modern Wing When the $300 million expansion opens this week, visitors will find the museum easier to navigate and see 20th century masterpieces in a whole new light – from the sun". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ^ Lourgos, Angie Leventis (May 8, 2009). "Bridge to the art world – Art Institute's new overhead walkway brings Modern Wing to the rest of the city". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ^ "The Nichols Bridgeway: Fact Sheet" (PDF). The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ^ "New Art Institute bridge to shoot over Monroe Street". Chicago Tribune. March 9, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (June 24, 2008). "Footnotes". The New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Newbart, Dave (June 19, 2009). "New Angles on Burnham – 2 futuristic pavilions launch tribute to Plan of Chicago designer". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (June 22, 2008). "2 architects to design Burnham pavilions". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ a b Howard, Hilary (July 19, 2009). "Comings & Goings; Chicago Celebrates An Urban Dream". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (June 14, 2009). "Pavilion opener awaits another day in park". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (June 18, 2009). "Populist gem joins 'Cloud Gate' at Millennium Park- Van Berkel's temporary pavilion an interactive salute to Burnham". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (August 4, 2009). "The Z-pod has landed: Delayed but worth the wait, Hadid's Burnham pavilion is a small structure that celebrates big plans". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ Crow, Kelly (July 24, 2009). "A New Monument—For a Few Months: As star architect designs for a Chicago park, costs and delays build". The Wall Street Journal. p. W12. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (August 9, 2009). "Fragile art takes a hit in an interactive world". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ Ford, Liam (July 11, 2004). "City to finally open its new front yard – Millennium Park's price tag tripled". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Weisberg, Lois and James Law (July 12, 2004). "Singing the praises of Millennium Park". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Macaluso, pp. 12–13

- ^ Gilfoyle, pp. 3–4

- ^ Sinkevitch, p. 37

- ^ Spielman, Fran (June 12, 2008). "Mayor gets what he wants – Council OKs move 33-16 despite opposition". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ "The taking of Grant Park". Chicago Tribune. June 8, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran and Art Golab (May 16, 2008). "13–2 vote for museum – Decision on Grant Park sets up Council battle". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Grinnell, Max (2005). "Grant Park". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ Macaluso, pp. 23–25

- ^ City of Chicago v. A Montgomery Ward, 169 Ill. 392 (1897)

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 16

- ^ E. R. Bliss v. A. Montgomery Ward, 198 Ill. 104; A. Montgomery Ward v. Field Museum of Natural History, 241 Ill. 496 (1909); and South Park Commissioners v. Ward & Co., 248 Ill. 299

- ^ a b c Gilfoyle, p. 181

- ^ Novak, Tim; Warmbir, Steve; Herguth, Robert; Brown, Mark (February 11, 2005). "City puts heat on clout-heavy cafe; Changes ordered at Park Grill, with Daley cronies among backers". Chicago Sun Times. p. 6, News section.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (May 9, 2007). "Millennium Park oversight plan advances". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 66, Financial section.

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 345.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (July 13, 2004). "Letter from Chicago; A Prized Project, a Mayor and Persistent Criticism". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (September 2, 2004). "Corporate logos in parks? Daley thinks it's 'fantastic' // Says companies deserve it if they foot the bill". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ von Rhein, John (September 14, 2008). "Expanding audiences and ambitions". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Sid (September 4, 2009). "Harris Theater ushers in lunchtime dance performances". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "City Charges To Publicly View Its Private Parts". Chicagoist. Gothamist LLC. September 1, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Downing, Andy (August 26, 2005). "Can Tori Amos pass the Millennium Park test?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Kim, Gina (July 19, 2004). "Cops seize college photographer's film". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ Kleiman, Kelly (March 30, 2005). "Who owns public art?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ Storch, Charles (May 27, 2005). "Millennium Park loosens its photo rules". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ "General Information". City of Chicago. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen S. (September 9, 2005). "No Walk In The Park – Toyota VIPs receive Millennium Park 's red-carpet treatment; everyone else told to just keep on going". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c Dardick, Hal (May 6, 2005). "This Sept. 8, No Bean For You – Unless you're a Toyota dealer. In that case, feel free to frolic because the carmaker paid $800,000 to own the park for the day". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ "A day in the park with Toyota". Chicago Tribune. May 10, 2005. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ Herrmann, Andrew (May 4, 2006). "Allstate pays $200,000 to book Millennium Park for one day". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ Stambor, Zak (July 23, 2009). "Chicago's dog beaches vary in breed". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ Roston, Eric (October 11, 2004). "Windy City Redux". Time. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ "Best Free Things to Do". Frommer's. Wiley Publishing, Inc. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ "In & Around the Loop". Frommer's. Wiley Publishing, Inc. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ "Millennium Park". Lonely Planet Publications. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ Cooper, Jeanne (July 18, 2004). "Travelers' Checks". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (December 18, 2004). "Best & Worst 2004: The Best Architecture". Time. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Spanberg, Erik (August 1, 2008). "New agenda on open space: Study of uptown park plans is expected to highlight need for more". Charlotte Business Journal. American City Business Journals, Inc. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- ^ Schultz, Patricia. 1,000 Places to See in the U.S.A. & Canada Before You Die. Workman Publishing. pp. 490–491. ISBN 0761136916.

- ^ "Best Sellers: August 13, 2006". The New York Times. August 13, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ King, John (November 19, 2006). "Holiday Goodies Between Covers: Our reviewers' picks of the best books of the season for the readers on your list". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ^ Deyer, Joshua (2005). "Chicago's New Class Act" (PDF). PN. Paralyzed Veterans of America. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Awards". Green Roofs for Healthy Cities. 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ "Contemporary Urban Waterscapes: designing public spaces in concert with nature". Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Bernstein, Fred A. (July 18, 2004). "Art/Architecture; Big Shoulders, Big Donors, Big Art". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Creature comforts". July 18, 2004. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ King, John (December 9, 2005). "San Francisco: Mayor widens vision to urban architecture. He doesn't want a 'dumbing down of quality' in design". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved July 31, 2008.