Lucid dream

A lucid dream, in simplest terms, is a dream in which one is aware that one is dreaming. The term was coined by the Dutch psychiatrist and writer Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932).[1]

A lucid dream can begin in one of two ways. A dream-initiated lucid dream (DILD) starts as a normal dream, and the dreamer eventually concludes it is a dream, while a wake-initiated lucid dream (WILD) occurs when the dreamer goes from a normal waking state directly into a dream state, with no apparent lapse in consciousness.

Lucid dreaming has been researched scientifically, and its existence is well established.[2][3]

Scientists such as Allan Hobson, with his neurophysiological approach to dream research, have helped to push the understanding of lucid dreaming into a less speculative realm.

Scientific history

The first book to recognize the scientific potential of lucid dreams was Celia Green's 1968 study Lucid Dreams.[4] Green analyzed the main characteristics of such dreams. She reviewed previously published literature on the subject, and incorporated new data from subjects of her own. She concluded that they were a category of experience quite distinct from ordinary dreams, and predicted that they would turn out to be associated with rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep). Green was also the first to link lucid dreams to the phenomenon of false awakenings.

In the early 1970s, Daniel Oldis of the University of South Dakota leveraged the scientific principle of external sensory incorporation in an attempt to influence dream content and evoke lucidity. Three psychological techniques were employed: subconscious suggestion using a tape played before and during sleep; associative signaling using a muffled bell alarm timed to go off during REM sleep; and classical conditioning using a REM detection circuit and a bright eye-light. The results indicated that lucid dreaming can be facilitated using external cues and psychological methods.[5]

Philosopher Norman Malcolm's 1959 text Dreaming[6] had argued against the possibility of checking the accuracy of dream reports. However, the realization that eye movements performed in dreams affected the dreamer's physical eyes provided a way to prove that actions agreed upon during waking life could be recalled and performed once lucid in a dream. The first evidence of this type was produced in the late 1970s by British parapsychologist Keith Hearne. A volunteer named Alan Worsley used eye movement to signal the onset of lucidity, which were recorded by a polysomnograph machine.

Hearne's results were not widely distributed. The first peer-reviewed article was published some years later by Stephen LaBerge at Stanford University, who had independently developed a similar technique as part of his doctoral dissertation.[7] During the 1980s, further scientific evidence to confirm the existence of lucid dreaming was produced as lucid dreamers were able to demonstrate to researchers that they were consciously aware of being in a dream state (again, primarily using eye movement signals).[8] Additionally, techniques were developed which have been experimentally proven to enhance the likelihood of achieving this state.[9] Research on techniques and effects of lucid dreaming continues at a number of universities and other centers, including LaBerge's Lucidity Institute.

Research and clinical applications

Neurobiological model

Neuroscientist J. Allan Hobson has hypothesized what might be occurring in the brain while lucid. The first step to lucid dreaming is recognizing that one is dreaming. This recognition might occur in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is one of the few areas deactivated during REM sleep and where working memory occurs. Once this area is activated and the recognition of dreaming occurs, the dreamer must be cautious to let the dream delusions continue but be conscious enough to recognize them. While maintaining this balance, the amygdala and parahippocampal cortex might be less intensely activated.[10] To continue the intensity of the dream hallucinations, it is expected the pons and the parieto-occipital junction stay active.[11]

Treatment for nightmares

It has been suggested that sufferers of nightmares could benefit from the ability to be aware they are indeed dreaming. A pilot study was performed in 2006 that showed that lucid dreaming treatment was successful in reducing nightmare frequency. This treatment consisted of exposure to the idea, mastery of the technique, and lucidity exercises. It was not clear what aspects of the treatment were responsible for the success of overcoming nightmares, though the treatment as a whole was successful.[12]

Australian psychologist Milan Colic has explored the application of principles from narrative therapy with clients' lucid dreams, to reduce the impact not only of nightmares during sleep, but also depression, self-mutilation, and other problems in waking life. Colic found that clients' preferred direction for their lives, as identified during therapeutic conversations, could lessen the distressing content of dreams, while understandings about life—and even characters—from lucid dreams could be invoked in "real" life with marked therapeutic benefits.[13]

Perception of time

The rate at which time passes while lucid dreaming has been shown to be about the same as while waking. However, a 1995 study in Germany indicated that lucid dreaming can also have varied time spans, in which the dreamer can control the length. The study took place during sleep and upon awakening, and required the participants to record their dreams in a log and how long the dreams lasted. In 1985, LaBerge performed a pilot study where lucid dreamers counted out ten seconds while dreaming, signaling the end of counting with a pre-arranged eye signal measured with electrooculogram recording.[14] LaBerge's results were confirmed by German researchers in 2004. The German study, by D. Erlacher and M. Schredl, also studied motor activity and found that deep knee bends took 44% longer to perform while lucid dreaming.[15]

Awareness and reasoning

While dream control and dream awareness are correlated, neither requires the other—LaBerge has found dreams which exhibit one clearly without the capacity for the other; also, in some dreams where the dreamer is lucid and aware they could exercise control, they choose simply to observe.[17] In 1992, a study by Deirdre Barrett examined whether lucid dreams contained four "corollaries" of lucidity: knowing that dreamt people are indeed dreamt, that objects won't persist beyond waking, that physical laws need not apply, and having clear memory of the waking world, and found less than a quarter of lucidity accounts exhibited all four. A related and reciprocal category of dreams that are lucid in terms of some of these four corollaries, but miss the realization that "I'm dreaming" were also reported. Scores on these corollaries and correctly identifying the experience as a dream increased with lucidity experience.[18] In a latter study in Barrett's book, The Committee of Sleep, she describes how some experienced lucid dreamers have learned to remember specific practical goals such as artists looking for inspiration seeking a show of their own work once they become lucid or computer programmers looking for a screen with their desired code. However, most of these dreamers had many experiences of failing to recall waking objectives before gaining this level of control.[19]

Near-death and out-of-body experiences

In a study of fourteen lucid dreamers performed in 1991, people who perform wake-initiated lucid dreams operation (WILD) reported experiences consistent with aspects of out-of-body experiences such as floating above their beds and the feeling of leaving their bodies.[20] Due to the phenomenological overlap between lucid dreams, near death experiences, and out-of-body experiences, researchers say they believe a protocol could be developed to induce a lucid dream similar to a near-death experience in the laboratory.[21]

Cultural history

Even though it has only come to the attention of the general public in the last few decades, lucid dreaming is not a modern discovery. A letter written by St. Augustine of Hippo in 415 AD refers to lucid dreaming.[22] In the eighth century, Tibetan Buddhists and Bonpo were practicing a form of Dream Yoga held to maintain full waking consciousness while in the dream state.[23] This system is extensively discussed and explained in the book Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light.[24] One of the important messages of the book is the distinction between the Dzogchen meditation of Awareness and Dream Yoga. The Dzogchen Awareness meditation has also been referred to by the terms Rigpa Awareness, Contemplation, and Presence. Awareness during the sleep and dream states is associated with the Dzogchen practice of natural light. This practice only achieves lucid dreams as a secondary effect—in contrast to Dream yoga which is aimed primarily at lucid dreaming. According to Buddhist teachers, the experience of lucidity helps us to understand the unreality of phenomena, which would otherwise be overwhelming during dream or the death experience.

An early recorded lucid dreamer was the philosopher and physician Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682). Browne was fascinated by the world of dreams and described his own ability to lucid dream in his Religio Medici: "... yet in one dream I can compose a whole Comedy, behold the action, apprehend the jests and laugh my self awake at the conceits thereof".[25] Similarly, Samuel Pepys in his diary entry for 15 August 1665 records a dream "that I had my Lady Castlemayne in my arms and was admitted to use all the dalliance I desired with her, and then dreamt that this could not be awake, but that it was only a dream". Marquis d'Hervey de Saint-Denys was probably the first person to argue that it is possible for anyone to learn to dream consciously. In 1867, he published his book Les Reves et les moyens de les diriger; observations pratiques (Dreams and How to Guide them; Practical Observations), in which he documented more than twenty years of his own research into dreams.

The term lucid dreaming was coined by Dutch author and psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden in his 1913 article "A Study of Dreams".[1] This paper was highly anecdotal and not embraced by the scientific community. Some consider this a misnomer because it means much more than just "clear or vivid" dreaming.[26] The alternative term conscious dreaming avoids this confusion. However, the term lucid was used by van Eeden in its sense of "having insight", as in the phrase a lucid interval applied to someone in temporary remission from a psychosis, rather than as a reference to the perceptual quality of the experience which may or may not be clear and vivid.

In the 1950s, the Senoi hunter-gatherers of Malaysia were reported to make extensive use of lucid dreaming to ensure mental health, although later studies refuted these claims.[27]

Induction methods

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

The examples and perspective in this article may not include all significant viewpoints. (April 2010) |

Many people report having experienced a lucid dream during their lives, often in childhood. Children seem to have lucid dreams more easily than adults. Over time, several techniques have been developed to achieve a lucid dreaming state intentionally. The following are common factors that influence lucid dreaming and techniques that people use to help achieve a lucid dream:

Dream recall

Dream recollection is the ability to remember dreams. Good dream recall is often described as the first step towards lucid dreaming. Better recall increases awareness of dreams in general; with limited dream recall, any lucid dreams one has can be forgotten entirely. To improve dream recall, some people keep a dream journal, writing down any dreams remembered the moment one awakes. An audio recorder can also be very helpful.[28] It is important to record the dreams as quickly as possible as there is a strong tendency to forget what one has dreamt.[29] For best recall, the waking dreamer should keep eyes closed while trying to remember the dream, and one's dream journal should be recorded in the present tense.[28] Dream recall can also be improved by staying still after waking up,[29] so the principles of state-dependent memory may apply. Similarly, if the dreamer changes positions in the night, he or she may be able to recall certain events of his or her dream by testing different sleeping positions. [citation needed] Another easy technique to help improve dream recall is to simply repeat (in thoughts or out loud) "I shall remember my dreams," before falling asleep. Stephen LaBerge recommends that you remember at least one dream per night before attempting any induction methods.

Wake-initiated lucid dreams (WILD)

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (April 2010) |

The wake-initiated lucid dream occurs when "the sleeper enters REM sleep with unbroken self-awareness directly from the waking state".[30] There are many techniques aimed at entering a WILD. The key to these techniques is recognizing the hypnagogic stage, which is within the border of being awake and being asleep. If a person is successful in staying aware while this stage occurs, that person will eventually enter the dream state while being fully aware that it is a dream.

There are key times at which this state is best entered; while success at normal bedtime after having been awake all day is very difficult, it is relatively easy after sleeping for 3–7 hours or in the afternoon during a nap. Techniques for inducing WILDs abound. Dreamers may count, envision themselves climbing or descending stairs, chant to themselves, control their breathing, count their breaths to keep their thoughts from drifting, concentrate on relaxing their body from their toes to their head, or allow images to flow through their "mind's eye" and envision themselves jumping into the image to maintain concentration and keep their mind awake, while still being calm enough to let their bodies sleep.

During the actual transition into the dream state, dreamers are likely to experience sleep paralysis, including rapid vibrations,[20] a sequence of loud sounds, and a feeling of twirling into another state of body awareness, or of "drifting off into another dimension", or like passing the interface between water into air, face front, body first, or the gradual sharpening and becoming "real" of images or scenes they are thinking of and trying to visualize gradually, which they can actually "see", instead of the indefinite sensations they feel when trying to imagine something while wide awake.

Reality testing

Reality testing (or reality checking) is a common method used by people to determine whether or not they are dreaming. It involves performing an action and observing if the results are consistent with results which would be expected in a state of wakefulness. By practicing these tests during waking life, one may eventually decide to perform such a test while dreaming, which may fail and let the dreamer realize that he or she is dreaming.

- The pain test -- "Pinch me, I think I'm dreaming!" -- is only effective in very few dreams. In Stephen LaBerge's book Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming it is proven that dreamed action produces real effects on the brain and body. Therefore, if the dreamer pinches itself, it will indeed feel pain but it will be unlikely to induce lucidity, because the schema for pain in the dreamer's brain will activate and the dreamer will feel pain even if there is no real physical stimulus. This same logic applies for other sensations, such as pleasure, heat, cold and a variety of other feelings the dreamer could experience in the waking world.[31]

- Looking at text or one's digital watch (remembering the words or the time), looking away, and looking back. The text or time will probably have changed randomly and radically at the second glance or contain strange letters and characters. (Analog watches do not usually change in dreams, while text and digital watches have a great tendency to do so.)[32] A digital watch or clock may feature strange characters or the numbers all out of order.

- Flipping a light switch. Light levels rarely change as a result of the switch flipping in dreams.[33]

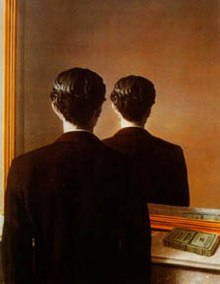

- Looking into a mirror; in dreams, reflections from a mirror often appear to be blurred, distorted, incorrect, or frightening.[33]

- Looking at the ground beneath one's feet or at one's hands. If one does this within a dream the difference in appearance of the ground or one's hands from the normal waking state is often enough to alert the conscious to the dream state.[34]

- If you listen to music while you sleep, listen to see if the lyrics are changed or if the tempo of the song changes.[citation needed]

A more precise form of reality testing involves examining the properties of dream objects to judge their apparent reality. Some lucid dreamers report that dream objects when examined closely have all the sensory properties, stability, and detail of objects in the physical world. Such detailed observation relates to whether mental objects and environments could effectively act as substitutes for the physical environments with the dreamer unable to see significant differences between the two. This has implications for those who claim there is a spiritual or supernatural world that might be accessible through out of body experiences or after death.[citation needed]

Prolongation

One problem faced by people wishing to experience lucid dreams is awakening prematurely. This premature awakening can be frustrating after investing considerable time into achieving lucidity in the first place. Stephen LaBerge proposed two ways to prolong a lucid dream. The first technique involves spinning one's dream body. He proposed that when spinning, the dreamer is engaging parts of the brain that may also be involved in REM activity, helping to prolong REM sleep. The second technique is rubbing one's hands. This technique is intended to engage the dreamer's brain in producing the sensation of rubbing hands, preventing the sensation of lying in bed from creeping into awareness. LaBerge tested his hypothesis by asking 34 volunteers to either spin, rub their hands, or do nothing. Results showed 90% of dreams were prolonged by hand rubbing and 96% prolonged by spinning. Only 33% of lucid dreams were prolonged with taking no action.[35]

Other variations on this theme have been proposed by lucid dream enthusiasts, the common basis for all these techniques is to focus on and/or increase ones tactile or sensory engagement with the dream world.

Other associated phenomena

Rapid eye movement (REM)

When a person is dreaming, the eyes move rapidly up and down and vibrate. Scientific research has found that these eye movements correspond to the direction in which the dreamer is "looking" in his/her dreamscape; this has enabled trained lucid dreamers to communicate whilst dreaming to researchers by using eye movement signals.[14]

False awakening

In a false awakening, one suddenly dreams of having been awakened. Commonly in a false awakening, the room is similar to the room in which the person fell asleep. If the person was lucid, they often believe that they are no longer dreaming and may start exiting the room and start going through a daily routine. This can be a nemesis in the art of lucid dreaming, because it usually causes people to give up their awareness of being in a dream, but it can also cause someone to become lucid if the person does a reality check whenever he/she awakens. People who keep a dream journal and write down their dreams upon awakening sometimes report having to write down the same dream multiple times because of this phenomenon. It has also been known to cause bed wetting as one may dream that they have awoken to go to the bathroom, but in reality are still dreaming. The makers of induction devices such as the NovaDreamer and the REM Dreamer recommend doing a reality check every time you awake so that when a false awakening occurs you will become lucid. People using these devices have most of their lucid dreams triggered through reality checks upon a false awakening.[36]

Sleep paralysis

During REM sleep the body paralyses itself as a protection mechanism in order to prevent the movements which occur in the dream from causing the physical body to move. However, it is possible for this mechanism to be triggered before, during, or after normal sleep while the brain awakens. This can lead to a state where a person is lying in bed and feels paralyzed. Hypnagogic hallucination may occur in this state, especially auditory ones. Effects of sleep paralysis include heaviness or inability to move the muscles, rushing or pulsating noises, and brief hypnogogic imagery. Experiencing sleep paralysis is a necessary part of WILD, in which dreamers essentially detach their "dream" body from the paralyzed one. Also see OBE or Out-Of-Body-Experience, opposing the scientific theory of these occurrences stating that the paralysis is actually an occurrence to one who is already "separated" from their physical body meaning that "physical action potentials" have no effect here but "mental actions" do - a hint given that those who are finding difficulty moving are using the wrong "mechanism".

Out-of-body experience

An out-of-body experience (OBE or sometimes OOBE) is an experience that typically involves a sensation of floating outside of one's body and, in some cases, perceiving one's physical body from a place outside one's body (autoscopy). About one in ten people think they have had an out-of-body experience at some time in their lives.[37] Scientists are learning about the phenomenon.[38]

OBEs induced from waking (with the intention of achieving Astral Projection) and lucid dreams induced from waking cover such similar ground that common misinterpretation of one as the other (or even equivalence) can be hypothesized.[39][unreliable source?] Realistic-seeming yet physically impossible impressions of flying, time-traveling or walking through the walls of an environment matching one's bedroom are equally hallmarks of either.[citation needed] (As those who have experienced them will attest,[who?] neither "feels" like ordinary dreams at all.[citation needed]) Their induction techniques are similar, and both are easier to perform at times typical for afternoon naps and late morning REM cycles.[citation needed]

Rarity and significance

| "We are asleep. Our life is a dream. But we wake up, sometimes, just enough to know that we are dreaming." |

| — Ludwig Wittgenstein[40] |

During most dreams, sleepers are not aware that they are dreaming. The reason for this has not been determined, and does not appear to have an obvious answer. There have been attempts by various fields of psychology to provide an explanation. For example, some proponents of Depth psychology suggest that mental processes inhibit the critical evaluation of reality within dreams. [41]

Physiology suggests that “seeing is believing” to the brain during any mental state. This being said, if the brain perceives something with great clarity or intensity, it will believe that it is real. Even waking consciousness is liable to accept discontinuous or illogical experience as real if presented as such to the brain.[42] Dream consciousness is similar to that of a hallucinating awake subject. Dream or hallucinatory images triggered by the brain stem are considered to be real, even if fantastic.[43] The impulse to accept the evident is so strong the dreamer will often invent a memory or story to cover up an incongruous or unrealistic event in the dream. “That man has two heads!” is usually followed not with “I must be dreaming!” but with “Yes, I read in the paper about these famous Siamese twins.” Or other times there will be an explanation that, in the dream, makes sense and seems very logical, but when the dreamer awakes, he/she will realize that it is rather far fetched or even complete gibberish.[44]

Developmental psychology suggests that the dream world is not bizarre at all when viewed developmentally, since we were dreaming as children before we learned all of the physical and social laws that train the mind to a “reality.” Fluid imaginative constructions may have preceded the more rigid, logical waking rules and continue on as a normative lifeworld alongside the acquired, waking life world. Dreaming and waking consciousness differ only in their respective level of expectations, the waking “I” expecting a stricter set of “reality rules” as the child matures. The experience of “waking up” normally establishes the boundary between the two lifeworlds and cues the consciousness to adapt to waking “I” expectations. At times, however, this cue is false—a false awakening. Here the waking “I” (with its level of expectations) is activated even though the experience is still hallucinatory. Incongruous images or illogical events during this type of dream can result in lucidity as the dream is being judged by waking “standards.”[45]

Another theory presented by transpersonal psychology and some Eastern religions is that it is the individual's state of consciousness (or awareness) that determines their ability to discriminate and differentiate between what is real, and what is false or illusory. In the dream state, many experiences are accepted as real by the dreamer that would not be accepted as real in the waking state. Some religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism describe states of consciousness (i.e., Nirvana or Moksha) where individuals "wake up", and discover a new or altered state of consciousness that reveals their normal waking experience to be unreal, dream-like, or maya (illusion). The assumption is that there are degrees of wakefulness or awareness, and that both lucid dreaming and normal waking experience lie somewhere towards the middle of this continuum (or hierarchy) of awareness. In this context, there must therefore be states of wakefulness that are superior to normal waking awareness. Just as when the dreamer awakens to realize that a nightmare was illusory, the individual can, like the Buddha, undergo a spiritual awakening and realize that what is called normal waking awareness is, in fact, a dream.[citation needed]

It has been[who?] hypothesized that meditation before sleep can also improve the occurrence of a lucid dream as it potentially minimizes the time taken for a person to fall asleep therefore increasing the chances of maintaining awareness to induce a lucid dream.[citation needed]

Maya

A Vedantic school called Advaita explains a state known as Maya. According to Sri Adi Shankara, any person who has become Brahma-jnani would come to know about physical world as an illusion just like a dream. He becomes one with his own Self, attains pure awareness, and sees the external, physical world as non-eternal untruth and illusion. That is a state of pure awareness and nothing else.

See also

- Yoga Nidra - the practice of sleep yoga

- Orphism (religion)

- Astral projection

- Dream argument

- Dream question

- Hemi-Sync

- List of dream diaries

- Pre-lucid dream

- Psychedelic

- Sleep paralysis

- The Art of Dreaming, non-fictional book

- Waking Life, film about a lucid dreamer

- Inception, film about lucid dreams.

Notes

- ^ a b Frederik van Eeden (1913). "A study of Dreams". Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research. 26.

- ^

Watanabe Tsuneo (2003). "Lucid Dreaming: Its Experimental Proof and Psychological Conditions". Journal of International Society of Life Information Science. 21 (1). Japan: 159–162.

The occurrence of lucid dreaming (dreaming while being conscious that one is dreaming) has been verified for four selected subjects who signaled that they knew they were dreaming. The signals consisted of particular dream actions having observable concomitants and were performed in accordance with a pre-sleep agreement.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

LaBerge, Stephen (1990). Bootzen, R. R., Kihlstrom, J.F. & Schacter, D.L., (Eds.) (ed.). Lucid Dreaming: Psychophysiological Studies of Consciousness during REM Sleep Sleep and Cognition. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. pp. 109–126.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Green, C., Lucid Dreams, London: Hamish Hamilton, .

- ^ Oldis, Daniel (1974). The Lucid Dream Manifesto. Plain Label Books. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-595-39539-2.

- ^ Malcolm, N., Dreaming, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1959.

- ^ Laberge, S. (1980). Lucid dreaming: An exploratory study of consciousness during sleep. (Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, 1980), (University Microfilms No. 80-24, 691)

- ^ LaBerge, Stephen (1990). in Bootzen, R. R., Kihlstrom, J.F. & Schacter, D.L., (Eds.): Lucid Dreaming: Psychophysiological Studies of Consciousness during REM Sleep Sleep and Cognition. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, pp. 109 – 126.

- ^ LaBerge, Stephen; Levitan, Lynne (1995). "Validity Established of DreamLight Cues for Eliciting Lucid Dreaming". Dreaming 5 (3). International Association for the Study of Dreams.

- ^ Muzur A, Pace-Schott EF (2002). "The prefrontal cortex in sleep" (PDF). Trends Cogn Sci. 1, 2(11): 475–481. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01992-7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hobson, J. Allan (2001). The Dream Drugstore: Chemically Altered States of Consciousness. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0262582209.

- ^

Spoormaker,-Victor-I; van-den-Bout,-Jan (2006). "Lucid Dreaming Treatment for Nightmares: A Pilot Study". Psychotherapy-and-Psychosomatics. 75 (6): 389–394. doi:10.1159/000095446. PMID 17053341.

Conclusions: LDT seems effective in reducing nightmare frequency, although the primary therapeutic component (i.e. exposure, mastery, or lucidity) remains unclear

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Colic, M. (2007). 'Kanna's lucid dreams and the use of narrative practices to explore their meaning.' The International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work (4): 19-26.

- ^ a b LaBerge, S. (2000). "Lucid dreaming: Evidence and methodology". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 23 (6): 962–3. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00574020.

- ^ Erlacher, D. (2004). "Required time for motor activities in lucid dreams" ([dead link]Scholar search). Perceptual and Motor Skills. 99 (3 Pt 2): 1239–1242. doi:10.2466/PMS.99.7.1239-1242. PMID 15739850.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Karma Triyana Dharmachakra Lineage History, The first Karmapa Düsum Khyenpa. Source: [1] (accessed: February 20, 2010)

- ^ Kahan, T., & LaBerge, S. (1994). Lucid dreaming as metacognition: Implications for cognitive science. Consciousness and Cognition 3, 246-264.

- ^ Barrett, Deirdre. Just how lucid are lucid dreams? Dreaming: Journal of the Association for the Study of Dreams, Vol 2(4) 221-228, Dec 1992

- ^ [http://www.amazon.com/Committee-Sleep-Scientists-Athletes-Solving/dp/0982869509/ref=tmm_pap_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1280437749&sr=8-1-spell Barrett, Deirdre The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use their Dreams for Creative Problem Solving . . .and How You Can, Too. Hardback Random House, 2001, Paperback Oneroi Press, 2010.

- ^ a b Lynne Levitan (1991). "Other Worlds: Out-of-Body Experiences and Lucid Dreams". Nightlight. 3 (2–3). The Lucidity Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Green, J. Timothy (1995). "Lucid dreams as one method of replicating components of the near-death experience in a laboratory setting". Journal-of-Near-Death-Studies. 14: 49-.

A large phenomenological overlap among lucid dreams, out-of-body experiences, and near-death experiences suggests the possibility of developing a methodology of replicating components of the near-death experience using newly developed methods of inducing lucid dreams. Reports on the literature of both spontaneous and induced near-death-experience-like episodes during lucid dreams suggest a possible protocol.

- ^ "Letter from St. Augustine of Hippo". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ (March 2005). The Best Sleep Posture for Lucid Dreaming: A Revised Experiment Testing a Method of Tibetan Dream Yoga. The Lucidity Institute.

- ^ Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light, 2nd edition, Snowlion Publications; authored by Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, an eminent Tibetan Lama, and his student Michael Katz, a Psychologist and lucid dream trainer.

- ^ Religio Medici, part 2:11. Text available at Uchicago.edu

- ^ Blackmore, Susan (1991). "Lucid Dreaming: Awake in Your Sleep?". Skeptical Inquirer. 15: 362–370.[dead link] Scholar search

- ^ G. William Domhoff (2003). Senoi Dream Theory: Myth, Scientific Method, and the Dreamwork Movement. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ^ a b Webb, Craig (1995). "Dream Recall Techniques: Remember more Dreams". The DREAMS Foundation.

- ^ a b Stephen LaBerge (1989). "How to Remember Your Dreams". Nightlight. 1 (1). The Lucidity Institute.

- ^ Stephen LaBerge (1995). "Validity Established of Dreamlight Cues for Eliciting Lucid Dreaming". Dreaming. 5 (3). The Lucidity Institute: 159–168.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ 41

- ^ Reality testing, Lucid Dreaming FAQ at The Lucidity Institute. (October 2006)

- ^ a b Lynne Levitan, Stephen LaBerge (Summer 1993). "The Light and Mirror Experiment". Nightlight. 5 (10). The Lucidity Institute.

- ^ H. von Moers-Messmer, "Traume mit der gleichzeitigen Erkenntnis des Traumzustandes," Archiv Fuer Psychologie 102 (1938): 291-318.

- ^ Stephen LaBerge (1995). "Prolonging Lucid Dreams". NightLight. 7 (3–4). The Lucidity Institute.

- ^ Lucidity.com, NovaDreamer Operation Manual

- ^ First Out-of-body Experience Induced In Laboratory Setting. ScienceDaily (August 24, 2007)

- ^ Out-of-body or all in the mind? BBC news (2005).

- ^ "Mastering astral projection: 90-day guide to out-of-body experience", Robert Bruce & Brian Mercer, p415. ISBN 0-7387-0467-9

- ^ Wittgenstein - Engelmann: Briefe, Begegnungen, Erinnerungen, (Innsbruck 2006), Paul Engelmann, Ludwig Wittgenstein

- ^ Sparrow, Gregory Scott (1976). Lucid Dreaming: Dawning of the Clear Light. A.R.E Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 87604-086-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ LaBerge, Stephen (2004). Lucid Dreaming: A Concise Guide to awakening in Your Dreams and in Your Life. Sounds True. p. 15. ISBN 1-59179-150-2.

- ^ Jouvet, Michel (1999). The Paradox of Sleep: The Story of Dreaming. MIT Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-262-10080-0.

- ^ McLeester, Ed. (1976). Welcome to the Magic Theater: A Handbook for Exploring Dreams. Food for Thought. p. 99. OCLC 76-29541.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ Oldis, Daniel (1974). Lucid Dreams, Dreams and Sleep. USD Press. pp. 173–178, 191. ISBN 978-1-60303-496-8.

Further reading

- Barton, Mary E. (2008). Soul Sight: Projections of Consciousness and Out of Body Epiphanies. ISBN 978-0-557-02163-5.

- Brooks, Janice (2000). The Conscious Exploration of Dreaming. Bloomington, IN: 1st Books Library. ISBN 1-58500-539-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Castaneda, Carlos. The Art of Dreaming. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

- Conesa-Sevilla, Jorge (2004). Amazon.com, Wrestling With Ghosts: A Personal and Scientific Account of Sleep Paralysis--and Lucid Dreaming. Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris. ISBN 978-1413446685.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Conesa-Sevilla, Jorge (2003). Sleep Paralysis Signaling (SPS) As A Natural Cueing Method for the Generation and Maintenance of Lucid Dreaming. Presented at The 83rd Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, May 1–4, 2003, in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

- Conesa-Sevilla, Jorge (2002). SleepAndHypnosis.org Isolated Sleep Paralysis and Lucid Dreaming: Ten-year longitudinal case study and related dream frequencies, types, and categories. Sleep and Hypnosis, 4, (4), 132-143.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - de Saint-Denys, Hervey (1982). Dreams and How to Guide Them. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1584-X.

- Gackenbach, Jayne (1988). Conscious Mind, Sleeping Brain. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-42849-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Garfield, Patricia L. (1974). Creative Dreaming. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21903-0.

- Godwin, Malcom (1994). The Lucid Dreamer. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-87248-6.

- Green, Celia (1968). Lucid Dreams. Oxford: Institute of Psychophysical Research. ISBN 0-900076-00-3.

- Green, Celia (1994). Lucid Dreaming: The Paradox of Consciousness During Sleep. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11239-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - LaBerge, Stephen (1985). Lucid Dreaming. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher. ISBN 0-87477-342-3.

- LaBerge, Stephen (1991). Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-37410-X.

- McElroy, Mark (2007). Lucid Dreaming for Beginners: Simple Techniques for Creating Interactive Dreams. Woodbury, Minn.: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0-7387-0887-4.

- Oldis, Daniel (1974). "Lucid Dreams, Dreams and Sleep: Theoretical Constructions". Univ. of South Dakota. Plain Label Books. ISBN 978-1-60303-840-9.

- Oldis, Daniel (2010). "Multi-Player Dream Games" (PDF). Lucid Dream Exchange. 54: 5–6.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Robert Waggoner (2008). Lucid Dreaming Gateway to the Inner Self. Needham, Mass.: Moment Point Press. ISBN 978-1-930491-14-4.

- Wangyal Rinpoche, Tenzin (1998). Tibetan Yoga Of Dream And Sleep. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publ. ISBN 1-55939-101-4.

- Warren, Jeff (2007). "The Lucid Dream". The Head Trip: Adventures on the Wheel of Consciousness. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0679314080.

- Yuschak, Thomas (2006). Advanced Lucid Dreaming - The Power of Supplements. United States?: Lulu Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-4303-0542-2.

- Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreams (MILD)

- Wake-back-to-bed (WBTB)

External links

- Lucid dreaming, an external wiki

- Template:Dmoz

- ABC News Video: How to Guide your Dreams