Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 9, 1737[1] |

| Died | June 8, 1809 (aged 72) |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Enlightenment, Liberalism, Radicalism, Republicanism |

Main interests | Religion, Ethics, Politics |

| Signature | |

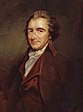

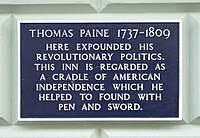

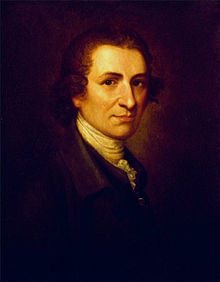

Thomas "Tom" Paine (February 9, 1737 [O.S. January 29, 1736[1]]– June 8, 1809) was an author, pamphleteer, radical, inventor, intellectual, revolutionary, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.[2][3] He has been called "a corsetmaker by trade, a journalist by profession, and a propagandist by inclination."[4]

Born in Thetford, in the English county of Norfolk, Paine emigrated to the British American colonies in 1774 in time to participate in the American Revolution. His principal contributions were the powerful, widely read pamphlet Common Sense (1776), advocating colonial America's independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain, and The American Crisis (1776–1783), a pro-revolutionary pamphlet series. His writing of "Common Sense" was so influential in spurring on the Revolutionary War that John Adams reportedly said, "Without the pen of the author of 'Common Sense,' the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.”[5]

In 1789 Paine visited France, and lived there for much of the following decade. He was deeply involved in the early stages of the French Revolution. He wrote the Rights of Man (1791), in part a defence of the French Revolution[3] against its critics, in particular the British statesman Edmund Burke. Despite not speaking French, he was elected to the French National Convention in 1792. The Girondists regarded him as an ally, so, the Montagnards, especially Robespierre, regarded him as an enemy. In December of 1793, he was arrested and imprisoned in Paris, then released in 1794. He became notorious because of The Age of Reason (1793–94), his book advocating deism, promoting reason and freethinking, and arguing against institutionalized religion and Christian doctrines.[3] He also wrote the pamphlet Agrarian Justice (1795), discussing the origins of property, and introduced the concept of a guaranteed minimum income.

Paine remained in France during the early Napoleonic era, but condemned Napoleon's dictatorship, calling him "the completest charlatan that ever existed".[6] In 1802, at President Jefferson's invitation, he returned to America where he died on June 8, 1809. Only six people attended his funeral as he had been ostracized due to his criticism and ridicule of Christianity.[7]

Early life

Paine was born February 9, 1737 [O.S. January 29, 1736] the son of Joseph Pain, or Paine, a Quaker, and Frances (née Cocke), an Anglican, in Thetford, an important market town and coach stage-post, in rural Norfolk, England.[8] Born Thomas Pain, despite claims that he changed his family name upon his emigration to America in 1774,[9] he was using Paine in 1769, whilst still in Lewes, Sussex.[10]

He attended Thetford Grammar School (1744–1749), at a time when there was no compulsory education.[11] At age thirteen, he was apprenticed to his stay-maker father; in late adolescence, he enlisted and briefly served as a privateer,[12][13] before returning to Britain in 1759. There, he became a master stay-maker, establishing a shop in Sandwich, Kent. On September 27, 1759, Thomas Paine married Mary Lambert. His business collapsed soon after. Mary became pregnant, and, after they moved to Margate, she went into early labour, in which she and their child died.

In July 1761, Paine returned to Thetford to work as a supernumerary officer. In December 1762, he became an excise officer in Grantham, Lincolnshire; in August 1764, he was transferred to Alford, at a salary of £50 per annum. On August 27, 1765, he was fired as an Excise Officer for "claiming to have inspected goods he did not inspect." On July 31, 1766, he requested his reinstatement from the Board of Excise, which they granted the next day, upon vacancy. While awaiting that, he worked as a stay maker in Diss, Norfolk, and later as a servant (per the records, for a Mr. Noble, of Goodman's Fields, and for a Mr. Gardiner, at Kensington). He also applied to become an ordained minister of the Church of England and, per some accounts, he preached in Moorfields.[14]

In 1767, he was appointed to a position in Grampound, Cornwall; subsequently, he asked to leave this post to await a vacancy, thus, he became a schoolteacher in London. On February 19, 1768, he was appointed to Lewes, East Sussex, living above the fifteenth-century Bull House, the tobacco shop of Samuel Ollive and Esther Ollive.

There, Paine first became involved in civic matters, when Samuel Ollive introduced him to the Society of Twelve, a local, élite intellectual group that met semestrally, to discuss town politics. He also was in the influential vestry church group that collected taxes and tithes to distribute among the poor. On March 26, 1771, at age 34, he married Elizabeth Ollive, his landlord's daughter.

From 1772 to 1773, Paine joined excise officers asking Parliament for better pay and working conditions, publishing, in summer of 1772, The Case of the Officers of Excise, a twenty-one-page article, and his first political work, spending the London winter distributing the 4,000 copies printed to the Parliament and others. In spring of 1774, he was fired from the excise service for being absent from his post without permission; his tobacco shop failed, too. On April 14, to avoid debtor's prison, he sold his household possessions to pay debts. On June 4, he formally separated from wife Elizabeth and moved to London, where, in September, a friend introduced him to Benjamin Franklin, who suggested emigration to British colonial America, and gave him a letter of recommendation. In October, Thomas Paine emigrated from Great Britain to the American colonies, arriving in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774.

He barely survived the transatlantic voyage. The ship's water supplies were bad, and typhoid fever killed five passengers. On arriving at Philadelphia, he was too sick to debark. Benjamin Franklin's physician, there to welcome Paine to America, had him carried off ship; Paine took six weeks to recover his health. He became a citizen of Pennsylvania "by taking the oath of allegiance at a very early period."[15] In January, 1775, he became editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine, a position he conducted with considerable ability.

Paine designed the Sunderland Bridge of 1796 over the Wear River at Wearmouth, England. It was patterned after the model he had made for the Schuylkill River Bridge at Philadelphia in 1787, and the Sunderland arch became the prototype for many subsequent voussoir arches made in iron and steel.[16][17] He also received a British patent for a single-span iron bridge, developed a smokeless candle,[18] and worked with inventor John Fitch in developing steam engines.

American Revolution

Common Sense (1776)

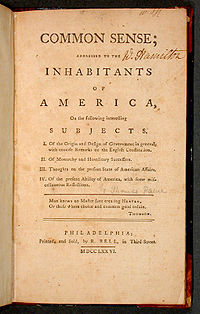

Thomas Paine has a claim to the title The Father of the American Revolution because of Common Sense, the pro-independence monograph pamphlet he anonymously published on January 10, 1776; signed "Written by an Englishman", the pamphlet became an immediate success.[19] It quickly spread among the literate, and, in three months, 100,000 copies sold throughout the American British colonies (with only two million free inhabitants), making it a best-selling work in eighteenth-century America.[20] Paine's original title for the pamphlet was Plain Truth; Paine's friend, pro-independence advocate Benjamin Rush, suggested Common Sense instead.

The pamphlet appeared in January 1776, after the Revolution had started. It was passed around, and often read aloud in taverns, contributing significantly to spreading the idea of republicanism, bolstering enthusiasm for separation from Britain, and encouraging recruitment for the Continental Army. Paine provided a new and convincing argument for independence by advocating a complete break with history. Common Sense is oriented to the future in a way that compels the reader to make an immediate choice. It offers a solution for Americans disgusted and alarmed at the threat of tyranny.[21]

Paine was not expressing original ideas in Common Sense, but rather employing rhetoric as a means to arouse resentment of the Crown. To achieve these ends, he pioneered a style of political writing suited to the democratic society he envisioned, with Common Sense serving as a primary example. Part of Paine's work was to render complex ideas intelligible to average readers of the day, with clear, concise writing unlike the formal, learned style favored by many of Paine's contemporaries.[22] Scholars have put forward various explanations to account for its success, including the historic moment, Paine's easy-to-understand style, his democratic ethos, and his use of psychology and ideology.[23]

Common Sense was immensely popular in disseminating to a very wide audience ideas that were already in common use among the elite who comprised Congress and the leadership cadre of the emerging nation. They rarely cited Paine's arguments in their public calls for independence.[24] The pamphlet probably had little direct influence on the Continental Congress's decision to issue a Declaration of Independence, since that body was more concerned with how declaring independence would affect the war effort.[25] Paine's great contribution was in initiating a public debate about independence, which had previously been rather muted.

Loyalists vigorously attacked Common Sense; one attack, titled Plain Truth (1776), by Marylander James Chalmers, said Paine was a political quack[26] and warned that without monarchy, the government would "degenerate into democracy".[27] Even some American revolutionaries objected to Common Sense; late in life John Adams called it a "crapulous mass." Adams disagreed with the type of radical democracy promoted by Paine, and published Thoughts on Government in 1776 to advocate a more conservative approach to republicanism.

Crisis (1776)

In late 1776 Paine published The Crisis pamphlet series, to inspire the Americans in their battles against the British army. He juxtaposed the conflict between the good American devoted to civic virtue and the selfish provincial man.[28] To inspire his soldiers, General George Washington had The American Crisis, first Crisis pamphlet, read aloud to them.[29] It begins:

These are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as freedom should not be highly rated.

Foreign Affairs

In 1777, Paine became secretary of the Congressional Committee on Foreign Affairs. The following year, he alluded to continuing secret negotiation with France in his pamphlets; the resultant scandal and Paine's conflict with Robert Morris eventually led to Paine's expulsion from the Committee in 1779. However, in 1781, he accompanied John Laurens on his mission to France. Eventually, after much pleading from Paine, New York State recognised his political services by presenting him with an estate, at New Rochelle, New York, and Paine received money from Pennsylvania and from the US Congress at George Washington's suggestion. During the Revolutionary War, Paine served as an aide to the important general, Nathanael Greene. Paine's later years established him as "a missionary of world revolution."

Funding the Revolution

Paine accompanied Col. John Laurens to France and is credited with initiating the mission.[30] It landed in France in March 1781 and returned to America in August with 2.5 million livres in silver, as part of a "present" of 6 million and a loan of 10 million. The meetings with the French king were most likely conducted in the company and under the influence of Benjamin Franklin. Upon returning to the United States with this highly welcomed cargo, Thomas Paine and probably Col. Laurens, "positively objected" that General Washington should propose that Congress remunerate him for his services, for fear of setting "a bad precedent and an improper mode." Paine made influential acquaintances in Paris, and helped organize the Bank of North America to raise money to supply the army.[31]

Henry Laurens (the father of Col. John Laurens) had been the ambassador to the Netherlands, but he was captured by the British on his return trip there. When he was later exchanged for the prisoner Lord Cornwallis (in late 1781), Paine proceeded to the Netherlands to continue the loan negotiations. There remains some question as to the relationship of Henry Laurens and Thomas Paine to Robert Morris as the Superintendent of Finance and his business associate Thomas Willing who became the first president of the Bank of North America (in Jan. 1782). They had accused Morris of profiteering in 1779 and Willing had voted against the Declaration of Independence. Although Morris did much to restore his reputation in 1780 and 1781, the credit for obtaining these critical loans to "organize" the Bank of North America for approval by Congress in December 1781 should go to Henry or John Laurens and Thomas Paine more than to Robert Morris.

Paine bought his only house in 1783 on the corner of Farnsworth Avenue and Church Streets in Bordentown City, New Jersey, and he lived in it periodically until his death in 1809. This is the only place in the world where Paine purchased real estate.

Rights of Man

Having taken work as a clerk after his expulsion by Congress, Paine eventually returned to London in 1787, living a largely private life. However, his passion was again sparked by revolution, this time in France, which he visited in 1790. Edmund Burke, who had supported the American Revolution, did not likewise support the events taking place in France, and wrote the critical Reflections on the Revolution in France, partially in response to a sermon by Richard Price, the radical minister of Newington Green Unitarian Church. Many pens rushed to defend the Revolution and the Dissenting clergyman, including Mary Wollstonecraft, who published A Vindication of the Rights of Men only weeks after the Reflections. Paine wrote Rights of Man, an abstract political tract critical of monarchies and European social institutions. He completed the text on January 29, 1791. On January 31, he gave the manuscript to publisher Joseph Johnson for publication on February 22. Meanwhile, government agents visited him, and, sensing dangerous political controversy, he reneged on his promise to sell the book on publication day; Paine quickly negotiated with publisher J.S. Jordan, then went to Paris, per William Blake's advice, leaving three good friends, William Godwin, Thomas Brand Hollis, and Thomas Holcroft, charged with concluding publication in Britain. The book appeared on March 13, three weeks later than scheduled, and sold well.

Undeterred by the government campaign to discredit him, Paine issued his Rights of Man, Part the Second, Combining Principle and Practice in February 1792. It detailed a representative government with enumerated social programs to remedy the numbing poverty of commoners through progressive tax measures. Radically reduced in price to ensure unprecedented circulation, it was sensational in its impact and gave birth to reform societies. An indictment for seditious libel followed while government agents followed Paine and instigated mobs, hate meetings, and burnings in effigy. The authorities aimed, with ultimate success, to chase Paine out of Great Britain and then try him in absentia.

In summer of 1792, he answered the sedition and libel charges thus: "If, to expose the fraud and imposition of monarchy ... to promote universal peace, civilization, and commerce, and to break the chains of political superstition, and raise degraded man to his proper rank; if these things be libellous ... let the name of libeller be engraved on my tomb".[32]

Paine was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, and was granted, along with Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and others, honorary French citizenship. Despite his inability to speak French, he was elected to the National Convention, representing the district of Pas-de-Calais.[33] He voted for the French Republic; but argued against the execution of Louis XVI, saying that he should instead be exiled to the United States: firstly, because of the way royalist France had come to the aid of the American Revolution; and secondly because of a moral objection to capital punishment in general and to revenge killings in particular. He participated to the Constitution Committee that drafted the Girondin constitutional project.[34]

Regarded as an ally of the Girondins, he was seen with increasing disfavour by the Montagnards who were now in power, and in particular by Robespierre. A decree was passed at the end of 1793 excluding foreigners from their places in the Convention (Anacharsis Cloots was also deprived of his place). Paine was arrested and imprisoned in December 1793.

The Age of Reason

Before his arrest and imprisonment in France, knowing that he would probably be arrested and executed, Paine, following in the tradition of early eighteenth-century British deism, wrote the first part of The Age of Reason, an assault on organized "revealed" religion combining a compilation of inconsistencies he found in the Bible with his own advocacy of deism, calling for "free rational inquiry" into all subjects, especially religion. The Age of Reason critique on institutionalized religion resulted in only a brief upsurge in deistic thought in America, but would later result in Paine being derided by the public and abandoned by his friends.[3] In his "Autobiographical Interlude," which is found in The Age of Reason between the first and second parts, Paine writes, "Thus far I had written on the 28th of December, 1793. In the evening I went to the Hotel Philadelphia ... About four in the morning I was awakened by a rapping at my chamber door; when I opened it, I saw a guard and the master of the hotel with them. The guard told me they came to put me under arrestation and to demand the key of my papers. I desired them to walk in, and I would dress myself and go with them immediately."

Being held in France, Paine protested and claimed that he was a citizen of America, which was an ally of Revolutionary France, rather than of Great Britain, which was by that time at war with France. However, Gouverneur Morris, the American ambassador to France, did not press his claim, and Paine later wrote that Morris had connived at his imprisonment. Paine thought that George Washington had abandoned him, and he was to quarrel with Washington for the rest of his life. Years later he wrote a scathing open letter to Washington, accusing him of private betrayal of their friendship and public hypocrisy as general and president, and concluding the letter by saying "the world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an impostor; whether you have abandoned good principles or whether you ever had any."[35]

While in prison, Paine narrowly escaped execution. A guard walked through the prison placing a chalk mark on the doors of the prisoners who were due to be sent to the guillotine the next day. He placed a 4 on the door of Paine's cell, but Paine's door had been left open to let a breeze in, because Paine was seriously ill at the time. That night, his other three cell mates closed the door, thus hiding the mark inside the cell. The next day their cell was overlooked. "The Angel of Death" had passed over Paine. He kept his head and survived the few vital days needed to be spared by the fall of Robespierre on 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794).[36]

Paine was released in November 1794 largely because of the work of the new American Minister to France, James Monroe,[37] who successfully argued the case for Paine's American citizenship.[38] In July 1795, he was re-admitted into the Convention, as were other surviving Girondins. Paine was one of only three deputees to oppose the adoption of the new 1795 constitution, because it eliminated universal suffrage, which had been proclaimed by the Montagnard Constitution of 1793.[39]

In 1797, Tom Paine lived in Paris with Nicholas Bonneville and his wife, Margaret. Paine, as well as Bonneville's other controversial guests, aroused the suspicions of authorities. Bonneville hid the Royalist Antoine Joseph Barruel-Beauvert at his home and employed him as a proofreader. Beauvert had been outlawed following the coup of 18 Fructidor on September 4, 1797. Paine believed that America, under John Adams, had betrayed revolutionary France and so in September 1798 he wrote an article for Le Bien Informé, advising the French government on how best to conquer America.[40] Bonneville was then briefly jailed for comparing Napoleon Bonaparte to Oliver Cromwell, in his publication 'The Well Informed of 19 Brumaire Year VIII,' and his presses were confiscated, which meant financial ruin.

In 1800, still under police surveillance, Bonneville took refuge with his father in Evreux. Paine stayed on with him, helping Bonneville with the burden of translating the Covenant Sea. The same year, Paine purportedly had a meeting with Napoleon. Napoleon claimed he slept with a copy of Rights of Man under his pillow and went so far as to say to Paine that "a statue of gold should be erected to you in every city in the universe."[41] Paine discussed with Napoleon how best to invade England and in December 1797 wrote two essays, one of which was pointedly named Observations on the Construction and Operation of Navies with a Plan for an Invasion of England and the Final Overthrow of the English Government,[42] in which he promoted the idea to finance 1000 gunboats to carry a French invading army across the English Channel. In 1804 Paine returned to the subject, writing To the People of England on the Invasion of England advocating the idea.[40]

On noting Napoleon's progress towards dictatorship, he condemned him as: "the completest charlatan that ever existed".[43] Thomas Paine remained in France until 1802, returning to the United States only at President Jefferson's invitation.

Later years

In 1802 or 1803, Tom Paine left France for the United States, paying passage also for Bonneville's wife, Marguerite Brazier and their three sons, seven year old Benjamin, Louis, and Thomas, of which Paine was godfather. Paine returned to the US in the early stages of the Second Great Awakening and a time of great political partisanship. The Age of Reason gave ample excuse for the religiously devout to dislike him, and the Federalists attacked him for his ideas of government stated in Common Sense, for his association with the French Revolution, and for his friendship with President Jefferson. Also still fresh in the minds of the public was his Letter to Washington, published six years before his return.

Upon his return to America, Paine penned 'On the Origins of Freemasonry.' Nicholas Bonneville printed the essay in French. It was not printed in English until 1810, when Marguerite posthumously published his essay, which she had culled from among his papers, as a pamphlet containing an edited version wherein she omitted his references to the Christian religion. The document was published in English in its entirety in New York in 1918.[44]

Brazier took care of Paine at the end of his life and buried him on his death on June 8, 1809. In his will, Paine left the bulk of his estate to Marguerite, including 100 acres (40.5 ha) of his farm so she could maintain and educate Benjamin and his brother Thomas. In 1810, The fall of Napoleon finally allowed Bonneville to rejoin his wife in the United States where he remained for four years before returning to Paris to open a bookshop.

Death

Paine died at the age of 72, at 59 Grove Street in Greenwich Village, New York City on the morning of June 8, 1809. Although the original building is no longer there, the present building has a plaque noting that Paine died at this location.

After his death, Paine's body was brought to New Rochelle, but no Christian church would receive it for burial, so his remains were buried under a walnut tree on his farm. In 1819, the English agrarian radical journalist William Cobbett dug up his bones and transported them back to England, with plans for English democrats to give Paine a heroic reburial on his native soil, but this never came to pass. The bones were still among Cobbett's effects when he died over twenty years later, but were later lost. There is no confirmed story about what happened to them after that, although down the years various people have claimed to own parts of Paine's remains, such as his skull and right hand.[45][46][47]

At the time of his death, most American newspapers reprinted the obituary notice from the New York Citizen, which read in part: "He had lived long, did some good and much harm." Only six mourners came to his funeral, two of whom were black, most likely freedmen. The writer and orator Robert G. Ingersoll wrote:

Thomas Paine had passed the legendary limit of life. One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred – his virtues denounced as vices – his services forgotten – his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul. He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death. Even those who loved their enemies hated him, their friend – the friend of the whole world – with all their hearts. On the 8th of June, 1809, death came – Death, almost his only friend. At his funeral no pomp, no pageantry, no civic procession, no military display. In a carriage, a woman and her son who had lived on the bounty of the dead – on horseback, a Quaker, the humanity of whose heart dominated the creed of his head – and, following on foot, two negroes filled with gratitude – constituted the funeral cortege of Thomas Paine.[48]

Political views

Thomas Paine developed his natural justice beliefs in childhood, while listening to a mob jeering and attacking the town folk being punished in the Thetford stocks.[citation needed] He may also have been influenced by his Quaker father.[49] In The Age of Reason– the treatise supporting deism– he says:

The religion that approaches the nearest of all others to true deism, in the moral and benign part thereof, is that professed by the Quakers ... though I revere their philanthropy, I cannot help smiling at [their] conceit; ... if the taste of a Quaker [had] been consulted at the Creation, what a silent and drab-colored Creation it would have been! Not a flower would have blossomed its gaieties, nor a bird been permitted to sing.

Later, his encounters with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas made a deep impression. The ability of the Iroquois to live in harmony with nature while achieving a democratic decision making process, helped him refine his thinking on how to organize society.[50]

In the second part of The Age of Reason, about his sickness in prison, he says: ". . . I was seized with a fever, that, in its progress, had every symptom of becoming mortal, and from the effects of which I am not recovered. It was then that I remembered, with renewed satisfaction, and congratulated myself most sincerely, on having written the former part of 'The Age of Reason'". This quotation encapsulates its gist:

The opinions I have advanced ... are the effect of the most clear and long-established conviction that the Bible and the Testament are impositions upon the world, that the fall of man, the account of Jesus Christ being the Son of God, and of his dying to appease the wrath of God, and of salvation, by that strange means, are all fabulous inventions, dishonorable to the wisdom and power of the Almighty; that the only true religion is Deism, by which I then meant, and mean now, the belief of one God, and an imitation of his moral character, or the practice of what are called moral virtues– and that it was upon this only (so far as religion is concerned) that I rested all my hopes of happiness hereafter. So say I now– and so help me God.

Paine was once often credited with writing "African Slavery in America", the first article proposing the emancipation of African slaves and the abolition of slavery. It was published on March 8, 1775 in the Postscript to the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser (aka The Pennsylvania Magazine and American Museum).[51] Citing a lack of evidence that Paine was the author of this anonymously published essay, some scholars (Eric Foner and Alfred Owen Aldridge) no longer consider this one of his works. By contrast, John Nichols speculates that his "fervent objections to slavery" led to his exclusion from power during the early years of the Republic.[52][dubious – discuss]

His last, great pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, he published in winter of 1795, further developing the ideas in the Rights of Man, about how land ownership separated the majority of people from their rightful, natural inheritance, and means of independent survival. Contemporarily, his proposal is deemed a form of basic Income Guarantee. [citation needed] The US Social Security Administration recognizes Agrarian Justice as the first American proposal for an old-age pension; per Agrarian Justice:

In advocating the case of the persons thus dispossessed, it is a right, and not a charity ... [Government must] create a national fund, out of which there shall be paid to every person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen pounds sterling, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property. And also, the sum of ten pounds per annum, during life, to every person now living, of the age of fifty years, and to all others as they shall arrive at that age.

Note that £10 and £15 would be worth about £800 and £1,200 when adjusted for inflation.[53]

Religious views

About religion, The Age of Reason says:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church. All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

He also wrote An Essay on the Origin of Free-Masonry (1803-1805), about the Bible being allegorical myth describing astrology:

The Christian religion is a parody on the worship of the sun, in which they put a man called Christ in the place of the sun, and pay him the adoration originally payed to the sun.

He described himself as deist, saying:

How different is [Christianity] to the pure and simple profession of Deism! The true Deist has but one Deity, and his religion consists in contemplating the power, wisdom, and benignity of the Deity in his works, and in endeavoring to imitate him in everything moral, scientifical, and mechanical.

Legacy

Thomas Paine's writing greatly influenced his contemporaries and, especially, the American revolutionaries. His books provoked only a brief upsurge in Deism in America, but in the long term inspired philosophic and working-class radicals in the UK, and US liberals, libertarians, feminists, democratic socialists, social democrats, anarchists, freethinkers, and progressives often claim him as an intellectual ancestor. Paine's critique on institutionalized religion and advocation of rational thinking influenced many British freethinkers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as William Cobbett, George Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh and Bertrand Russell.

Many of Paine's works have also been an inspiration for rapidly expanding secular humanism. His Deism and his writings on Deism have inspired the creation of the World Union of Deists and the writing of the book Deism: A Revolution in Religion, A Revolution in You.

Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln's law partner, William Herndon, reports that Lincoln wrote a defense of Paine's deism in 1835, and friend Samuel Hill burned it to save Lincoln's political career.[54] Historian Roy Basler, the editor of Lincoln's papers, said Paine had a strong influence on Lincoln's style:

- No other writer of the eighteenth century, with the exception of Jefferson, parallels more closely the temper or gist of Lincoln's later thought. In style, Paine above all others affords the variety of eloquence which, chastened and adapted to Lincoln's own mood, is revealed in Lincoln's formal writings.[55]

Edison

The inventor Thomas Edison said:

I have always regarded Paine as one of the greatest of all Americans. Never have we had a sounder intelligence in this republic ... It was my good fortune to encounter Thomas Paine's works in my boyhood ... it was, indeed, a revelation to me to read that great thinker's views on political and theological subjects. Paine educated me, then, about many matters of which I had never before thought. I remember, very vividly, the flash of enlightenment that shone from Paine's writings, and I recall thinking, at that time, 'What a pity these works are not today the schoolbooks for all children!' My interest in Paine was not satisfied by my first reading of his works. I went back to them time and again, just as I have done since my boyhood days.[56]

Memorials

On the site of Paine's farm in New Rochelle are located the Thomas Paine Cottage and the Thomas Paine Historical Society Museum.[57] In England a statue of Paine, quill pen and inverted copy of Rights of Man in hand, stands in King Street, Thetford, Norfolk, his birth place. Moreover, in Thetford, the Sixth form is named after him.[58] Thomas Paine was ranked #34 in the 100 Greatest Britons 2002 extensive Nationwide poll conducted by the BBC [59]

Bronx Community College includes Paine in its Hall of Fame of Great Americans, and there are statues of Paine in Morristown and Bordentown, New Jersey, and in the Parc Montsouris, in Paris.[60][61] Also in Paris, there is a plaque in the street where he lived from 1797 to 1802, that says: "Thomas PAINE / 1737–1809 / Englishman by birth / American by adoption / French by decree". Yearly, between 4 and 14 July, the Lewes Town Council in the United Kingdom celebrates the life and work of Thomas Paine.[62]

In the early 1990s, largely through the efforts of citizen activist David Henley of Virginia, legislation (S.Con.Res 110, and H.R. 1628) was introduced in the 102nd Congress by ideological opposites Sen. Steve Symms (R-ID) and Rep. Nita Lowey (D-NY), and later(with technical corrections) was passed by both houses of Congress. In October, 1992 the legislation was signed into law (PL102-407 & PL102-459) by President George H.W. Bush authorizing the construction, using private funds, of a memorial to Thomas Paine in "Area 1" of the grounds of the US Capitol. As of January 2011[update], the memorial has not yet been built. With over 100 formal letters of endorsement by US and foreign historians, philosophers, and organizations including the Thomas Paine National Historical Society, the legislation earned 78 original co-sponsors in the US Senate and 230 original co-sponsors in the US House of Representatives, and was consequently passed by unanimous consent.

-

Statue in Thetford, Norfolk, England, Paine's birthplace

-

Thomas Paine Museum, 983 North Avenue, New Rochelle, New York

-

Monument to Paine in New Rochelle

-

Statue in Bordentown City, New Jersey

See also

|

References

- Notes

- ^ a b Conway, Moncure D. (1892). The Life of Thomas Paine. Volume 1, page 3. Retrieved on 18 July 2009.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard B. (2009). The Founding Fathers Reconsidered. Oxford University Press US. p. 36. ISBN 0195338324. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d Thomas Paine "These are the times that try men's souls". USHistory.org. Retrieved on 18 July 2009.

- ^ Saul K. Padover, Jefferson: A Great American's Life and Ideas, New York: The New American Library, 1952, p. 32

- ^ The Sharpened Quill The New Yorker, Accessed November 6, 2010,

- ^ Original source of this quotation is Henry York, Letters from France, Two volumes (London, 1804). Thirty three pages of the last letter are devoted to Paine.

- ^ Conway, Moncure D. (1892). The Life of Thomas Paine. Volume 2, pages 417-418. Retrieved on 18 July 2009.

- ^ Crosby, Alan (1986). A History of Thetford (1st ed.). Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore & Co Ltd. pp. 44–84. ISBN 0 85033 604 X. (Also see discussion page )

- ^ Ayer, Alfred Jules (1990). Thomas Paine. University of Chicago Press. p. 1. ISBN 0226033392.

- ^ "National Archives" (Document). UK National Archives.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|document=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ School History Thetford Grammar School, Accessed January 3, 2008,

- ^ Rights of Man II Chapter V

- ^ Thomas had intended to serve under the ill-fated Captain William Death, but was dissuaded by his father. Bring the Paine!

- ^ Conway, Moncure Daniel (1892). "The Life of Thomas Paine: With a History of Literary, Political, and Religious Career in America, France, and England". Thomas Paine National Historical Association. p. Volume 1, page 20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ Conway, Moncure Daniel, 1892. The Life of Thomas Paine vol. 1 p. 209

- ^ History of Bridge Engineering, H.G. Tyrrell, Chicago, 1911

- ^ A biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland at 753-755, A. W. Skempton and M. Chrimes, ed.,Thomas Telford, 2002 (ISBN 0-7277-2939-X, 9780727729392)

- ^ Thomas Paine, Independence Hall Association. Accessed online November 4, 2006.

- ^ Introduction to Rights of Man, Howard Fast, 1961

- ^ Oliphant, John. "?". "Paine,Thomas". Charles Scribner's Sons (accessed via Gale Virtual Library). Retrieved 2007-04-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Robert A. Ferguson, "The Commonalities of Common Sense," William and Mary Quarterly, July 2000, Vol. 57#3 pp 465-504 in JSTOR

- ^ Merrill Jensen, The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution, 1763–1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), 668.

- ^ David C. Hoffman, "Paine and Prejudice: Rhetorical Leadership through Perceptual Framing in Common Sense," Rhetoric and Public Affairs, Fall 2006, Vol. 9 Issue 3, pp 373-410

- ^ Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Knopf, 1997), 90-91.

- ^ Jack N. Rakove, The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress (New York: Knopf, 1979), 89.

- ^ New, M. Christopher. "James Chalmers and Plain Truth A Loyalist Answers Thomas Paine". "Archiving Early America". Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Jensen, Founding of a Nation, 669.

- ^ Martin Roth, "Tom Paine and American Loneliness," Early American Literature, Sept 1987, Vol. 22 Issue 2, pp 175-82

- ^ "Thomas Paine. The American Crisis. Philadelphia, Styner and Cist, 1776-77". Indiana University. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ^ Daniel Wheeler's Life and Writings of Thomas Paine Volume 1 (1908) p. 26-27:

- ^ Daniel Wheeler's Life and Writings of Thomas Paine Volume 1 (1908) p. 314

- ^ Thomas Paine, Letter Addressed To The Addressers On The Late Proclamation, in Michael Foot, Isaac Kramnick (ed.), The Thomas Paine Reader, p. 374

- ^ Fruchtman, Jack (2009). The Political Philosophy of Thomas Paine. Baltimore, MD, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 192. ISBN 0801892848.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.google.com/search?tbs=bks%3A1&tbo=1&hl=fr&q=Thomas+Paine+draft+constitution+1793&btnG=Chercher+des+livres

- ^ Paine, Thomas. "Letter to George Washington, July 30, 1796: "On Paine's Service to America"". Retrieved 2006-11-04.

- ^ Paine, Thomas; Rickman, Thomas Clio (1908). "The Life and Writings of Thomas Paine: Containing a Biography" (Document). Vincent Parke & Co. pp. 261–262.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Foot, Michael, and Kramnick, Isaac. 1987. The Thomas Paine Reader, p.16

- ^ Eric Foner, 1976. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. p. 244. Foner wrote, "... it was not until the arrival of the new American ambassador, James Monroe, who claimed Paine as a citizen of the United States, that he was released -- the "citizen of the world" saved by the principle of national citizenship."

- ^ Aulard, Alphonse. 1901. Histoire politique de la Révolution française, p.555

- ^ a b Mark Philp, 'Paine, Thomas (1737–1809)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2008, accessed July 26, 2008 (subscription required)

- ^ O'Neill, Brendan (2009-06-08). "Who was Thomas Paine?". BBC. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ "Papers of James Monroe... from the original manuscripts in the Library of Congress".

- ^ Craig Nelson. Thomas Paine. p. 299.

- ^ Fruchtman, Jack Jr. Thomas Paine: Apostle of Freedom. Basic Books. 1996. ISBN 1568580630, 9781568580630 accessed online April 12, 2010

- ^ "The Paine Monument at Last Finds a Home". The New York Times. October 15, 1905. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ Chen, David W. "Rehabilitating Thomas Paine, Bit by Bony Bit". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. p.510

- ^ Robert G. Ingersoll, Thomas Paine, written 1870, published New Dresden Edition, XI, 321, 1892. Accessed online at thomaspaine.org, February 17, 2007.

- ^ Claeys p. 20.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack "Indian Givers How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World".1988, p.125

- ^ Van der Weyde, William M., ed. The Life and Works of Thomas Paine. New York: Thomas Paine National Historical Society, 1925, p. 19-20.

- ^ Nichols, John (2009-01-20). "Obama's Vindication of Thomas Paine". The Nation (blog).

- ^ Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present

- ^ Herndon, William. "Abraham Lincoln's Religious Views". Positive Atheism. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ Roy P. Basler, ed. Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings (1946) p. 6.

- ^ Thomas Edison, Introduction to The Life and Works of Thomas Paine, Citadel Press, New York, 1945 Vol. I, p.vii-ix. Reproduced online on thomaspaine.org, accessed November 4, 2006.

- ^ "Museum". Thomas Paine National Historical Association. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ "Thomas Paine Sixth Form". Rosemary Musker High School. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ BBC - 100 great British heroes.

- ^ "Photos of Tom Paine and Some of His Writings". Morristown.org. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ "Parc Montsouris". Paris Walking Tours. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ The Tom Paine Project, Lewes Town Council. Retrieved November 4, 2006.

- Bibliography

- Aldridge, A. Owen, 1959. Man of Reason: The Life of Thomas Paine. Lippincott. Regarded by British authorities as the standard biography.

- Aldridge, A. Owen, 1984. Thomas Paine's American Ideology. University of Delaware Press.

- Ayer, A. J., 1988. Thomas Paine. University of Chicago Press.

- Bailyn, Bernard, 1990. "Common Sense", in Bailyn, Faces of Revolution: Personalities and Themes in the Struggle for American Independence. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Bernstein, R. B. "Review Essay: Rediscovering Thomas Paine". New York Law School Law Review, 1994 – valuable blend of historiographical essay and biographical/analytical treatment.

- Butler, Marilyn, 1984. Burke Paine and Godwin and the Revolution Controversy.

- Claeys, Gregory, 1989. Thomas Paine, Social and Political Thought. Unwin Hyman. Excellent analysis of Paine's thought.

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, 1892. The Life of Thomas Paine, 2 vols. G.P. Putnam's Sons. Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Facsimile. Long hailed as the definitive biography, and still valuable.

- Fast, Howard, 1946. Citizen Tom Paine (historical novel, though sometimes mistaken as biography).

- Ferguson, Robert A. "The Commonalities of Common Sense", William and Mary Quarterly, July 2000, Vol. 57#3 pp 465–504 in JSTOR

- Foner, Eric, 1976. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. Oxford University Press. The standard monograph treating Paine's thought and work with regard to America.

- Foot, Michael, and Kramnick, Isaac, 1987. The Thomas Paine Reader. Penguin Classics.

- Griffiths, Trevor (2004). "These Are the Times: A Life of Thomas Paine" (Document). Spokesman Books.

- Hawke, David Freeman, 1974. Paine. Regarded by many American authorities as the standard biography.

- Hitchens, Christopher, 2006. Thomas Paine's "Rights of Man": A Biography.

- Ingersoll, Robert G., 1892, "Thomas Paine," North American Review.

- Kates, Gary, 1989, "From Liberalism to Radicalism: Tom Paine's Rights of Man", Journal of the History of Ideas: 569–587.

- Kaye, Harvey J., 2005. Thomas Paine and the Promise of America. Hill and Wang.

- Keane, John, 1995. Tom Paine: A Political Life. London. One of the most valuable recent studies.

- Larkin, Edward, 2005. Thomas Paine and the Literature of Revolution. Cambridge University Press.

- Lessay, Jean. L'américain de la Convention, Thomas Paine: Professeur de révolutions. Paris, éditions Perrin, 1987, 241 p.

- Lewis, Joseph, 1947, "Thomas Paine: The Author of the Declaration of Independence". Freethought Association Press Assn.: New York.

- Nelson, Craig, 2006. Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. Viking. ISBN 0-670-03788-5.

- Paine, Thomas (Foner, Eric, editor), 1993. Writings. Library of America. Authoritative and scholarly edition containing Common Sense, the essays comprising the American Crisis series, Rights of Man, The Age of Reason, Agrarian Justice, and selected briefer writings, with authoritative texts and careful annotation.

- Paine, Thomas (Foner, Philip S., editor), 1944. The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 2 volumes. Citadel Press. We badly need a complete edition of Paine's writings on the model of Eric Foner's edition for the Library of America, but until that goal is achieved, Philip Foner's two-volume edition is a serviceable substitute. Volume I contains the major works, and volume II contains shorter writings, both published essays and a selection of letters, but confusingly organized; in addition, Foner's attributions of writings to Paine have come in for some criticism in that Foner may have included writings that Paine edited but did not write and omitted some writings that later scholars have attributed to Paine.

- Powell, David, 1985. Tom Paine, The Greatest Exile. Hutchinson.

- Russell, Bertrand (1934). "The Fate of Thomas Paine".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Vincent, Bernard, 2005. The Transatlantic Republican: Thomas Paine and the age of revolutions.

- Williams, Walton, July, 1994. "The Declaration of Independence: Was it Written by Thomas Paine?" The Crooked Lake Review (Reprinted from the Hammondsport Herald, July 6, 1906) http://www.crookedlakereview.com/articles/67_100/76july1994/76williams.html

- Wheeler, Daniel, Life and Writings of Thomas Paine, Vincent & Parke, 1908.

- Wilensky, Mark (2008). The Elementary Common Sense of Thomas Paine. An Interactive Adaptation for All Ages. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-932714-36-4.

- The Popular Encyclopedia London: Blackie & Sons 1875. "Thomas Paine"

External links

- The Thomas Paine Society

- Who was Thomas Paine?

- Essays on the Religious and Political Philosophy of Thomas Paine

- Thomas Paine's Memorial

- Thomas Paine Quotations

- Books of Our Time: Thomas Paine and the Promise of America by Harvey Kaye (video)

- Take a video tour of Thomas Paine's birthplace

- Office location while in Alford

- Thomas Paine-Passionate Pamphleteer for Liberty by Jim Powell

- Thomas Paine on Paper Money, 1786

- Thomas Paine, Liberty's Hated Torchbearer

- Lesson plan – Common Sense: The Rhetoric of Popular Democracy

- Books of Our Time: Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (video)

- Correspondence between Paine and Samuel Adams regarding the charge of infidelity

- One Life: Thomas Paine, the Radical Founding Father exhibition from the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

- Works

- Complete Works of Thomas Paine

- Template:Worldcat id

- Works by Thomas Paine at Project Gutenberg

- Deistic and Religious Works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine to which are appended the profession of faith of a savoyard vicar by J.J. Rousseau

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine; HTML format, indexed by section

- Rights of Man book on Google books (full-view)

- Listen to Common Sense at Americana Phonic. AAC audio format

- 1737 births

- 1809 deaths

- 18th-century English people

- Enlightenment philosophers

- 19th-century English people

- Burials in New York

- English writers

- American abolitionists

- American foreign policy writers

- American pamphlet writers

- Patriots in the American Revolution

- Political leaders of the American Revolution

- American revolutionaries

- American people of British descent

- British immigrants to the United States

- Deist thinkers

- Religious skeptics

- Deputies to the French National Convention

- American people of English descent

- English businesspeople

- British republicans

- Pennsylvania political activists

- People from Greenwich Village, New York

- People from New Rochelle, New York

- English inventors

- Kingdom of Great Britain migrants to the Thirteen Colonies

- People from Thetford

- The Enlightenment

- Classical liberals

- Prisoners sentenced to death by France

- Burial place unknown

- Agrarian theorists

- British people of the American Revolution