Prehistory of West Virginia

The area of the United States now known as West Virginia was a favorite hunting ground of numerous Native American peoples before the arrival of European settlers. Hunters from neighboring lowland states ventured into West Virginia's mountain valleys making temporary camp villages since the early archaic period. Many ancient man-made earthen mounds from various mound builder cultures survive, especially in the areas of Moundsville, South Charleston, and Romney. The artifacts uncovered in these give evidence of a village society having a tribal trade system culture that practiced limited cold worked copper. As of 2009, over 12,500 archaeological sites have been documented in the Mountain State (Bryan Ward 2009:10).[1]

Origins

In quote, "the nationalist, the collector, and the curator...each looks upon the past as a piece of property. Another approach is possible— to see our collective cultural remains as a resource whose title is vested in all humanity.", Karl E. Meyer, The Plundered Past (Meyer 1973:203).

Antiquity West Virginia, in a broad sense, can be characterized as evolving through acculturation and assimilation with a few exceptions. Nomadic Paleo-Indian hunted throughout the state using variations of spear points at the end of the Pleistocene. These evolved into the Mountain State's Archaic Indians living in temporary villages on the Kanawha region streams, Monongahela and Potomac tributaries streams of the Allegheny Mountains. The early regional Archaic adapted to use of basic Atlatls. Passing of time, an early Woodland culture coming from the east later began a friendly trade with the evolving Ohio Valley archaics. They brought with them the utility of steatite made bowls thought to be from the steatite in Virginia. These bowls were soon replaced in the valley by the making of local sand stone bowls. The Eastern Woodland continued the trade with the region's Archaic who became the Adena Mound Builders of the Ohio Valley. (Dragoo)[2] This acculturation led to an early tradition of large burial mounds built in the Mountain State. Popular examples of their mounds are the largest mounds which include: the St Albans site (Broyles 1968), Turkey Creek Mound (46PU2), Goff Mound, Reynolds Mound, St Mary's Mound, Camden Park Mound, Criel Mound, Grave Creek Mound, and Indian Mound Cemetery. The Grave Creek Mound in Moundsville is the largest and around its outer base was a moat. At Cresap Mound, Carnegy's Dr. Don Dragoo was able to provide greater detail which redefined what constitute Early-Middle Adena (BCE 1000) as opposed to Late Adena (BCE 500). Woodland cultures basically means the coming of the bow for fire making, shaft-end dressing of stick of wood (i.e. fish gigging rod or cooking rod, wood shaft hand tools) and some will later include the stone point arrow.

A leather rap "shoe" was likely common upon man's arrival to the Mountain State. The use of footwear protection seems to have started around 26,000 years ago long before the arrival of the Paleo Indian dates in West Virginia. "I discovered that the bones of the little toes of humans from that time frame were much less strongly built than those of their ancestors while their leg bones remained large and strong," explains Dr. Trinkaus of Washington University in St. Louis, Mo. "The most logical cause would be the introduction of supportive footwear." He analyzed the foot bones of western Eurasian Middle Paleolithic and middle Upper Paleolithic humans.[3] Thus far, science understands shoed human will arrive in the state after the Pleistocene Epoch (2.588 million to 12,000 years BC) or 6th epoch of the Cenozoic Era.[4] As once anonymously stated, The consequent history of the land become the participant— the nomadic Paleo-Indian.

During the Pleistocene's Wisconsin Glacial Episode, the Bering Sea fluctuated at least twice to become a dry landmass because of interglacial warm periods.[5] The land was called Beringia. This Bering land bridge was about (c.) the size as Alaska and connecting with Russia Chukotka Autonomous Okrug region. It was exposed at least twice from 75,000 to 45,000 BP, and again from 25,000 to 14,000 years ago (c. 24,000—c. 12,000 BC) according to The Digital Atlas of Idaho Project (DAI). The last waning Beringia had in places melting snow drifts reaching to the Brooks Range Glacier. The weather pattern, a consistent warm period, allowed a patchwork of vegetation along the coast and an earlier discovered corridor between the Cordilleran (western US-Canada) and Laurentian (eastern US-Canada) ice sheets. This passable land bridge had a band of developing boreal-like from a Tundra like Biome of flora spanning through Beringia to Montana and Idaho region. Beringia is suspected to have possible annual growth season of four or five months along more sheltered places. This allowed many animal Species and Paleo-Siberian hunters to pass between the two continents. Russian archaeologist, Yuri Mochanov has provided evidence and descriptive culture of the Siberian hunters from 14,000 to 12,000 years ago (c. 12,000—c. 10,000 BC). From studying teeth, scientist Cristy Turner exposed a possible migration route from the Aldan River (Upper Lena Basin) to the Sea of Okhotsk where scientists also suspect a possible migration along Beringian coast. Today's Bering Strait overlay Beringia where Inuit and Aleut peoples live along Bering Sea shores.

The last interglacial period was 125,000—75,000 BP. It preceded the colder Wisconsinan (Wisconsin) Stage with ice terrace advancement beginning c. 30,000 years ago and reaching a zenith around 21,000 years ago. About this time or by 18,000 years ago the now fluctuatingly warming weather ends the Stage approximately 10,000 years ago. Today's Interglacial period is called the Holocene geological Series Epoch and Yet to be named Stage Age which mark began at 11,700 years ago (Ogg, Smith and Gradstein et al. 2004, 2008.[6]). Paleo-Indian people lived in the previous Upper (Stage Age) of the Pleistocene epoch (Series Epoch) of the Quaternary (System Period) of the Cenozoic (Erathem Era) of the Phanerozoic (Eonothem Eon), from the International Commission on Stratigraphy (IS Chart 2008). It was after the Paleo people arrive in North America the saber-toothed cats, mammoths, mastodons, glyptodonts, horses, camels, among others, become extinct.

Local cultural anthropologists abstracts having preliminary interpretation provide clues of the spread of cultural items, or traits of idea and material found in collective identities, as suspected exchange through inter-cultural middleman trade, migration, direct trade and intermarriage, enslavement after warfare or simply mutual absorption between the peoples of the Prehistoric. The content of archaeological site projects within the state can often require years of lab research for scheduling and the resource funding considerations in finding which kind of knowledge exchange took place.

Mountains and rivers

West Virginia (WV) is within the physiographic provinces unglaciated Allegheny Plateau which include parts of the Allegheny Front and Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians easterly. These west (W) hills along the Ohio Valley climb east (E) up tributary streams to the base of the Allegheny Mountains. The lowest altitude averages 550 to 600 feet (170 to 180 m) above the sea, SW bottoms along the Ohio River (normal pool 538 feet (164 m)). Below the E slopes of the Allegheny Front c. 2,600 to 4,700 feet (790 to 1,430 m) peaks passing down the Potomac River on the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia are similar land altitudes having relief of up to c. 2,000 feet (610 m). The plateau reach from the SE Ohio (OH) through western WV easterly to the physiographic province, Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, became dissected with a summit level ranging from c. 1,200 to 1,800 feet (370 to 550 m) (Ehlers & Gibbard 2004:237). The tributary rivers commonly have broad rolling upper land having watersheding branches with steeper hills suitable for Grazing wildlife and today's farming agriculture. Here in the W central of the state the rushing colder mountain trout holding streams form the deeper warm water fish holding brooks and then smaller rivers feeding the Ohio River— the actual Plateau. The smaller rivers were once Gulf of Mexico distancing spawning rivers of migratory fish such as the ancient sturgeon (WVDNR). The highest peaks today in the state are over 4,800 feet (1,500 m). The Allegheny Mountains have no volcanic peaks and are rather quiet with very little and unnoticeable earth quake activity. The state mountains were formed by an Orogeny effect of the North American Plate.[8] The Taconic Orogeny near the end of Ordovician time formed a much higher mountainous area in E West Virginia approximately 350 million to 300 million years ago in the Carboniferous period. The plateau and mountains have a long history of erosion and throughout the region before peaking formation. The West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey in 2006, "These highlands formed the main source of sediments for the succeeding Silurian Period (c. 443 million years ago) and part of the Devonian Period (c. 416 million years ago)." Devonian was about the time lobe-finned fish developed legs (Tiktaalik) as they started to walk on land as tetrapods. The Mesozoic Era (c. 250 to c. 67 million years ago) of the Age of Dinosaurs is marked by Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event and following Cenozoic Era with the dominant terrestrial vertebrates mammals from c. 65.5 million years ago to the present— the Age of Mammals. Some of these ancient animal evidence are found as fossil between the geologic strata near the abundant sections of coal seams and nearby natural gas (fossil fuel ranges) in the state.

The Quaternary ice age (BC ~2.6 million) began about the time of Pleistocene Epoch. The weather had been by far milder. Sitting snugly in the then much higher mountains was Glacial Teays Lake, extending from SW Virginia through the New-Kanawha river to its northerly drainage river, the very ancient Teays River. It flowed through Ohio to central Indiana across Illinois to the Mississippi Valley. Lying on the north was the Pittsburgh drainage basin. (Jacobson, Elston and Heaton 1987:abstract[9]) The Mississippi at the time was an embayment of the Gulf of Mexico reaching to Illinois. Glacial Teays Lake last occurrence was c. 2 Million years ago when it outburst and the wash build up created the final large prehistoric lake in the western of the state. Lake Tight lasted only c. 6500 years before it outburst forming the Ohio Valley.[10] The Ohio-Allegheny system (Ohio Valley) on the western half of the state was in its present form by the Middle Pleistocene, c. 781 to 126 thousand years ago.[11] The remaining glacial lake in the northern area of the state was the glacial Monongahela Lake. It had been blocked by ice terraces or ice sheets in the north and western Pennsylvania. Upon ice retreat, it outburst through the basin to the north. It would reform with the next re-advancing glacial ice drift, ground rise and again, another late last occurrence with outwash build-up.

The last maximum extent (LGM) of glaciation was approximately 18,000 years ago.[12] This last returning advancement of glacial ice approaching the Ohio Valley began c. 30,000 years ago. West Virginia had no Ice Sheet buildup. Although during the Last Ice Age, smaller glaciation impounded lakes continued to collect precipitation on the plateau.[13] These chilly lakes among mountain peaks were separated from the continental ice sheet to the north. The deeply carved river valleys like the upper Canaan Valley to Blackwater Canyon and the Dolly Sods Wilderness to Cheat River areas are called Paleozoic Plateaus. The "Driftless Area" drains into rivers having rugged regions of bluffs and valleys. According to the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, the two large Ice Age lakes varied throughout the epoch. The last glacial lake, Monongahela, occurrence in the Mountain State "Carbon-14 dates of c. 22,000, 23,000, and 39,000 years old". It reached as far south as Weston into the state. Monongahela lake redeveloped and overflowed perhaps at several places as its age is older than 780,000 years BP (WVGES 2005). The first ice-damming event was a pre-Illinoian (Stage) lake which outburst during the earlier ice retreat towards the NW Pittsburgh drainage direction (Jacobson, Elston and Heaton 1987:abstract). The last occurrence of the Monongahela lake an outwash gravel dam backed up slackwater at Allegheny-Monongahela confluence during an Illinoian ponding event last glacial retreat. The last outburst drained to its present coarse, the central Allegheny Mountains or northern tributaries of the state feeding the Monongahela River to the Ohio River.

The Cirque and Tarn (lake) were among heads of smaller outwashes through the Allegheny Plateau. Some of these backed waters cut through leaving higher flatland or terraces among ridge tops above the major river bottoms of which runoff sheds. Higher in the state is Cranberry Glades example lay between Mountain ridge top and peeks with five small, boreal-type bogs. These feed the mountain river, Cranberry River, a trout-holding biom. From these various mountain and hill formations, the Allegheny Plateau has eroded and settled. In Pennsylvania the Titusville Till, results of very ancient Monongahela lake sediment, has an age of c. 40,000 years. There are several different strata of till layers across the region. Outflow of melt and weather contributed to the hill and mountain erosion. On top of the layers of geologic strata, settled drifts of kame or gravel shoals lay under soil sediments along the valley bottoms. "As one proceeds westward, the rocks are younger and younger," states Peter Lessing, July 1996, West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey. Below outcrops of the Paleozoic Plateaus are the largest kind of sediment by erosion, the large boulders peeking above the rivers surface. A variety of stone of geology for lithic tool making is found across the state in valleys (Brockman, US Forest Service, 2003). From these stone, artifacts are found providing evidence Paleo-Indians were passing through the Mountain State (Dragoo 1963). State universities and the U.S. Geological Survey Paleoanthropologists have found evidence of early Archaic people habitation during Holocene Climate Optimum—a rough interval of 9,000 to 5,000 years B.P.

Ecosystems and Migration

The state's ecosystems influenced the movement of the siminomadic Archaic Indian. The land gradually changed from a tundra to a boreal (i.e. evergreen forest or a Taiga) and eventually to a highland "oak-hemlock" (Rhododendron and Appalachian mixed mesophytic forests) or nut tree and berry forest (Dwyer 1999:14). Here, this attracted modern game animals followed by a new way of living for the nomadic hunters. The flora, according to the 2009 Historic Preservation Plan, as described, "Paleoenvironmental data suggest that modern deciduous forests had reached areas south and east of the Allegheny Front by ca. 7800 BC...Carbonized nut hulls from the St. Albans Site (46Ka61) in Kanawha County date to ca. 7000 BC and provide additional evidence in West Virginia of the increasing variety of food in people’s diets." The State's bioms are broad scope from boreal Cranberry Glades through to the Ohio River Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

Geography influenced the movement of both man and beast in the state. The central area has the New River (Kanawha River) flowing from the Ridge and Valley Province. Opposite the New River, the Head of the Tennessee River (Powell, Clinch and Holston valleys) drains south westerly the Ridge and Valley Province. The upper branches of the Big Sandy River (earliest called Osioto Mtns, Lewis & Evens 1750) drains this province's southerly northern slopes. While emptying near the mouth of the Ohio River, the Tennessee River and parallelingly north Cumberland River reaches from the west draining Cumberland Plateau opposite the Big Sandy watershed. The Tennessee River reaches easterly to the Ridge and Valley Province of the Great Smoky Mountains, part of the Blue Ridge Mountains which are a division of the larger Appalachian Mountain chain. The Potomac River, James River and Dan River basins drain the eastern slopes of these mountain ranges. Ancient mountain trails through eastern Kentucky and West Virginia allowed Native American passage between the northern Till Plains of Illinois, Indiana and Ohio, otherwise a part of the "Corn Belt" or Midwestern United States and the Piedmont Plateau, and Atlantic Ocean coastal plains. Many migration, trade and warrior trails with branching minor hunter paths were there across this greater region.

Between 10,800 and 9500 BC, the continental glaciers had retreet beyond the Great Lakes.[14] Glacial lake outburst floods occurred during the melt outflow and a couple of occurrences at times throughout these millenniums of Palaeo-Indian followed by Early Archaic.[15] Not only lake outburst, recent flood scouring disturbed lithics and ceramics in a thick near-surface layer of alluvium on the South Branch of the Potomac at the Romney bridge replacement archaeological site (GAI Consultants, Inc. (GAI) 2003).[16] Early Lake Erie (Lakes Michigan and Erie combined) had flowed west out Little River (Great Black Swamp proglacial lake's drainage embayment) and the Wabash River before changing direction to the east into Glacial Lake Iroquois.[17] An earlier sediments built up event outburst near the Little River. Over time, outflow sediments again built up. This time with land rise contributed to the change of drainage direction and the remaining Great Black Swamp. The Early Lake Erie finally assumed their present shapes about only 3,000 years ago— arising Woodland Period. Lake Erie's level was similar to Lake Nipioing phase of Lakes Michigan and Huron basins 5,000 BP. By 3,500 years BP the level had lowered by 4 meters and by 2,000 BP the level had increased to possibly 5 meters above today's levels.[17] This period (by 2,000 BP) saw the Hopewell culture arrive from the north in west central Ohio and Indiana in mass (Dragoo 1963, Carnegy Vol 37). These groups were preceded by similar trading people also from the north (Dragoo 1963). Of these earlier trade people also from the north, a vanguard Armstrong variant in SW West Virginia mingled peacefully with Late Adena (McMichael 1968). Native American cold worked copper from the pits in Wisconsin Old Copper Complex region have been found in some Adena mounds (USGS, Dragoo, McMichael et al. 1957, 1963, 1968; Cyrus Thomas, Smithsonian 1894, myth debunking scientist). The Upper Ohio Valley was experiencing the Sub-Atlantic climatic phase (c. 3000-1750 BP) of warm and moist climatic conditions and stable stream levels (USACE) upon the occurrence of the Hopewell culture. This climatic phase began after the much earlier arise of indigenous Early Adena Culture (46MR7 BCE 1735) in West Virginia (McMichael 1968).

The Mountain State's larger bottom lands and terraces are suitable for large scale crop rotation agriculture (Sandretto, Soil Management, USDA 2005). However, according to George Washington in 1770, many areas are not so relatively level land with narrow bottoms and not deep in fertile soils nor high in organic matter although good as Grazing land. He did find plenty suitable places for homesteading for his veterans as did Native Americans before him (LOC, Jackson & Twohig 1976:304~308). These earlier Native American were of migration while the frontier settlers were of Immigration or a Nation state Sovereignty concerning Emigration or naturalization by definition (Diner 2008[18]). The various earlier Native American arrived or arise in the state developing Iconic art (McMichael 1968:19 fig.15, p. 50 fig. 47) and a Wampum system. There was no modern written language in the state until European contact and the historic period. The prehistoric Native American were concerned not of a modern border demarcation of historic governments.

and: Appalachian mixed mesophytic forests

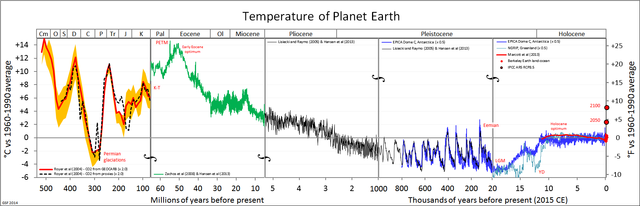

Paleoclimatology

The study by scholars of Paleoclimatology and required research of the United States Army Corps of Engineers provides insights of prehistorical weather. The last time of continental glaciers in the North America of the Laurentide ice sheet is called the Wisconsin Glacial Episode. This was the last advancement of glacial ice sheet. The colder weather began c. 30,000 years ago. This weather caused the ice sheet to advance until 23,500 to 21,000 years ago. During the warm weather thawing, pockets of colder temperature periods lasting from several hundred years to a little over 1000 years occurred. Temporary weather patterns are called stadial periods. The last brief cold period during the Wisconsin Glacial Episode lasted for c. 1,300 years from approximately 12,800 and 11,500 years ago. This freezing period temporarily stalled the ice sheet thawing north near the Great Lakes.[14] It is called the Younger Dryas Stadial with dates c. 10,800 and 9500 BC. There is clear archaeological evidence nomadic Paleo-Indian arrived in the upper Ohio Valley utilizing the Kanawha Black flint at this time. According to Illinois State Museum, "These climate changes were causing fundamental changes in the ecosystems of North America."

Richard L. Meehan of Stanford University characterized the Younger Dryas Stadial. Paraphrasing Stanford, as quickly by 12000 BP (c. 10,800 BC) temperatures plunged 7 degrees, the sea level had reached 100 feet below present level. The sea level hesitated, "the circulation system of the North Atlantic went into a kind of planetary fibrillation."[19] Excerpt from Stanford, "After a millennium, the end of the Younger Dryas (c. 9500 BC) came about almost as quickly as it had begun, warmth returned... a great green spring in the northern lands (Stanford U., Meehan 2010)."

The warm period during interval of c. 9,000 to 5,000 years ago is called the Holocene Climate Optimum. This was a period of steady warm weather for the indigenous Archaic Indian. After the great stall of temperate vegetational change due to long term weather, now the Indian were becoming less broad ranging nomadics in the Kanawha region (46Wd83-A). Towards the end of the Archaic Indian period of the Upper Ohio Valley and tributaries the seasonal weather was a time of meridional circulation and penetrations of large storms coming from the Gulf of Mexico. The region's Archaic had hunted smaller game and began fishing shifting their seasonal living between base camps. With some climatic overlapping, the western and northern valleys of West Virginia, in general, became warm and dry with less effective precipitation c. 4500 BP causing the bottom land flora to thin. This in turn caused an occasional major flood and serious erosion during the early part transitional weather pattern. The people of these days saw vegetation shifts reacting to climate in the state (S. Munoz et al., PNAS 2010).

The valley people's conscientious efforts to change was the beginning of agriculture and food storage pottery at the progressively more settled hamlet. Burial mounds appear and soon grow in size which also signals settling to area of an ancestral valley. The fickle drought period was followed by the following periods: Sub-Boreal climatic phase (c. 4200-3000 BP) cool and wet period, Sub-Atlantic climatic phase (c. 3000-1750 BP) warm and moist climatic conditions, Scandic climatic phase (c. 1750-1250 BP), Neo-Atlantic climatic phase (c. 1100-750 BP) meta-stable conditions, Pacific climatic phase (c. 750 BP, Little Ice Age) cool and wet periods (USACE). The weather patterns influenced the early people's culture of the state.

The prevailing weather pattern in the Middle Ohio Valley ca. AD 1350-1600 was cooler and wetter conditions followed by increasing frequency of droughts. In contrast, the upper Ohio Valley was experiencing milder weather patterns (Staller, Tykot and Benz 2006:226,227). The frequency of droughts in the Mountain State increased in the following decades. The data from this research, the authors write, is not convincing to determine drought frequency for ca. AD 1250-1400. However the development towards the north of the Allegheny Plateau, the Till Plains with natural fertile water-holding areas less effected by drought, was found in the earliest protohistoric period with expansive corn usage and growing villages (Mollenkopf 2005:37). These peoples (Olentangy River and upper Scioto), the Cole culture north of the central Ohio River, arrive the Sandusky culture[20] of the Great Black Swamp area tributary to Lake Erie. And, their easterly neighbors along the shores, the Whittlesey culture, "with a pallisade or a ditch, suggesting a need for defense".[21]

Rise and decline of the state's two true farmer culture's weather:

- Medieval Warm Period (~800-1300 AD)

- Little Ice Age Period (~1400-1900 AD)

The Eemian interglacial period (~130,000 to ~114,000 BP) was followed by the glaciating Wisconsin episode. Its climate is believed to be similar to today's Holocene period.

Earth and Ocean Sciences, Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA

Paleo-Indian

Paleo-Indian culture appears by 10,500 BC in West Virginia passing along the major river valleys and ridge-line gap watersheds. One of many cave shelters in the state can be exampled at the Paleo hunting shelter at "New Trout Cave" in Pendleton County. (Grady and Garton, 1981 Grady, 1986). The Faunmap for the cave shows an age from 17060 to 29400 years ago. To note, a "Faunmap" is not always directly concerned with artifacts found at a rockshelter site. However, a cut and charred fragment from a firepit becomes very significant. From his research at Wyandot County, Brian G. Redmond 'The Archaeology and Paleontology of Sheriden Cave' in the north-west Ohio area, "more than 60 species of animals which include extinct taxa such as flat-headed peccary (New World pig also found at Welsh Cave, Kentucky through to Texas), giant beaver, giant short-faced bear, and stag-moose. In contrast to this vast faunal assemblage are a preciously small number of artifacts which document an early Paleoindian occupation of the cave." Archaeological investigations at the site has continued since 1996 (The Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology 2006:abstract). This ancient habitation location was near the Lake Maumee. Today's Little River (Indiana) had drained this proglacial lake (Forsyth 1959). Nearby Great Black Swamp, drained in the 19th century, was also a remnant of the bed of the proglacial lake which had formed about 14,000 years ago. Among the Megafauna of the region, a few American mastodon teeth have been found on the broader river bottoms in western West Virginia. Washington County, Pennsylvania and Brooke County, West Virginia share the two state's border. Less than a dozen miles from the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia is Avella, Pennsylvania and nearby Meadowcroft Rockshelter.

Kanawha Chert was found at Meadowcroft Rockshelter (36WH297) Washington County, Pa.[23] Kanawha Chert source is 183.4 miles (114 km) southwest of Meadowcroft (Vento and Donahue 1982:116). Quoting, "The lithic raw material data indicate the early inhabitants of Meadowcroft Rockshelter had been in the region long enough to discover local chert sources, but also utilized or exploited materials from a much larger territory than just the local region. Alternatively, the exotic lithic materials may indicate trade with neighboring groups, if they were present at that time." Paleo occupation has been dated from 11,320~14,225 BC (radiocarbon date, Sciulli 1982:176).[24] As the Ice Age animals became extinct in the region, the Paleo or Clovis culture transition their hunted game and stone tool making from the fluted Clovis Point. The following Plano culture's spear point (8000-7000 BC) lack the groove or flute of the earlier Clovis Point. These extend westward now hunting bison on the High Plains extending to Ohio and into the early Archaic.[25] The Dalton Tradition (c. 8500-7900 BC, Goodyear 1982:389-392), or some of the cluster ranging to or through WV (Justice 1995:41), represents another technical shift and this cluster includes a type of adz (Justice 1995:41).

Archaeologist from the University of Cincinnati, Dr. Ken Tankersley, excavated an amazing site with evidence of Clovis people and the remains of their hunt of many extinct game dating 13,000 years ago in NW central Ohio. He found evidence of a serious Comet strike, not yet located, may have caused the Extinction of the Pleistocene giant mammals. Two other early neighboring sites, Cactus Hill in SE Virginia Clovis culture dated to 10,920 BP to dates ranging from c. 15,000 to 17,000 years ago and Saltville SW Virginia, dating 14,510 BP, having different weather patterns. A Pennsylvania archaeologist and field crew member, Dr. Mark McConaughy, during the 1974 season personally collected many of the samples at the Meadowcroft Rockshelter (Adovasio, et al. 1977; Carlisle and Adovasio 1982). Dr. Mark McConaughy in 14 January 1999 writes, "Pre-Clovis sites have to have artifacts dating older than 12,500 years ago." However controversial two other sample dates there at 17,650 BC (SI-2060, uncorrected) Pre-Clovis,[26] Paleo-Indian was living through central Ohio, upper Ohio Valley and Virginia Ridge and Valley to the Piedmont Plateau prior to the weather pattern of c. 10,800 BC through 9500 BC— Younger Dryas Stadial.

Archaic Indian

6700 to 5700 BCE

Occurs from northern Alabama north to New York and into Ohio, Michigan and eastern Kentucky (Broyles 1971).

The chronological cultural changes in general seems to have been by influx from the surrounding regions to the Mountain State. The earliest stone point surface finds, like the Dalton variants (8700 to 8200 BCE), are very rare. These become more common approaching the Mississippi Valley, example Sloan site (8500 BCE) in Missouri. An early, rare, Archaic stone point is exampled with the Kessell Side Notched point at the St. Albans Site which dated to 7900 BCE (Broyles 1971). Although nearly a thousand years earlier, it is similar to the early Big Sandy point (Lewis and Lewis 1961, Tenn.) and Fort Nottoway point (Gardner 1988, Virginia).

Anthropology helps explain from whom and where did the state's Archaic people arrive. According to the Geological Survey and written by Don Dragoo (1963), the longheaded Paleo-Indian ancestor of a southern Archaic Isawnid (i.e. Indian Knoll Culture of Kentucky) and the northern Archiac Lenid (Great Lakes Area) variety were well on its way by at least 6000 BC in eastern North America and by 4000 BC the two varieties were clearly separable (Dragoo 1963).[27] By 2500 BC the Archaic cultures of eastern North America had separated into two distinct phases; reverine (river-delta) environment in the south and those adapted to the lacustrine (lake-streams) resources of the north. A Mesoamerica population, the origin of the Walcolid and other brachycepalic (heads of high, round vaults) varieties from the Archaic South moved up to central Mississippi River area. They were located just below the Baumer Culture. They were a well differentiated Walcolid variety by 900 AD (Neumann 1960; Dragoo 1963; Sponemann Phase, Ill. Peregrine and Ember 2001:260). Recent research for example in her analysis of Seneca material in 1966, Dr. Sublett concluded the Clover Phase (one type of the many Fort Ancient people) were of the Lenapid variety. This variety has since been changed to Illinid and does not neccessarily mean northern Algonquan nor Iroquois(Fuerst 2002, CWVA). The physical types were based on Dr Neumann's Eastern Woodland, the Muskogids, Illinids, and Lenids. Late modern forensic anthropological work continues in the state.

The Lower Ohio Valley contrasting the upper Ohio Valley is considered a transition zone, or one of five zones of the Western Mesophytic Forest Region (Braun 1950:122). The not so dense deciduous forest terrestrial ecoregion were among open grasslands. Throughout this oak savannah territory held varyingly fields of cane, wild rye and clover areas of this called Bluegrass section (Jefferies 2009:26). The first Adena came into eastern Kentucky and assimilated the northern parts, pushing the Baumer south mixing with the Walcolid. A variant of the Copena Culture on the Tennessee River system became trademen from the Gulf of Mexico and the Adena (Dragoo). Dr Dragoo illustrated in his 1963 publication (Vol 37) the several coarse cloth of the broad Adena trade region. Of these precious few rarely found examples in the state were made of cotton. Cotton does not grow well within the state, wrong climate. Followingly, the Kentucky Adena intermixed with these along this trade route. These continued the Gulf Coastal trade up the Ohio Valley into West Virginia. It is thought Mesoamerican seeds' propagation would eventually progress in this way to the state.

Archaic are evidenced by the frequent use of ground-stone implements and flint woodworking tools in sites having bowls, knives, net sinkers, and elaborate weights for "spear-throwers" correctly called atlatl. The "atlatl & dart", this improved dart is not dynamically like a spear, become rather common about 4000 BC. The archaic stone point chronology in the Kanawha Valley generally begins with Kanawha Points of LeCroy Period (6200-6300 BC) and followed by the Stanley Period (~5745 BC), Amos Period (4365-4790 BC), Hansford Period (3600-3700 BC) ending with the Tansitional Period (1000-1200 BC) to Adena-Woodland (Kanawha Valley Archaeology Society). Some Brewerton Phase side and corner-notched points (Side-notched Tradition) are often found resharpened to a considerable extent, some having been modified as hafted end-scrapers. A few uncommon "Pointed Pole Adzes" are suspected to have been used for heavy wood works at one late northern "Panhandle Archaic" site (~2000 BC) by recent studies. A dug out canoe has been suggested. Not many centuries after the 4000 BC weather, in general, Red Ocher and Glacial Kame having connections with archaic Copena culture variation on the Tennessee River system began assimilating (Dragoo, 1963). Continued with the arising of the Adena, these trade system mix will derive the state's fort builder cultures over a millennium later (Dragoo).

In Woodland perspective comparison of period and date of earlier archaic mounds, the Lower Mississippi delta region has the Monte Sano mounds of c. 7,000 years old. The Frenchman’s Bend and Watson Brake mounds are thought to be close to 5,500 years old according to Rebecca Saunders, archaeology professor and associate curator of the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science. The Ohio Valley does not have the earliest mounds in North America. The archaic Copena culture was central to the Mississippi Valley (Dragoo 1963). Traditional thought has the greater Ohio Valley region latest archaic developing mounds in situ, otherwise, a progressing development of the Indigenous peoples (Geological Survey scholars of 1963). Late Archaic Kentucky trade preceded Adena Mound Builders.

Regional Archaic

The traditional Archaic sub-periods are Early (8000-6000 BC), Middle (6000-4000 BC), and Late (4000-1000 BC), (Kerr, 2010).

Transition to mounds

The West Virginia Archaic Traditions (7000-1000 BCE) evolved from the nomadic Paleo-Indian (before 11,000 BCE -Late Paleo ~9000 BCE, ◦Plano cultures) already in the greater region. The Archaic characteristics are not shared in any way with Asian people and rising Eastern Woodland period with exception of the Eskimos and the Athapascans of the north west North America. (Stewart 1960, p. 269) and (Dragoo 1963, p. 255) The burial mound complex of the Adena (Ohio Valley Mound Builders) is unlikely related to those in Asia because it was not in use in northeastern Asia at an early enough date according to Chard. (1961, p. 21-25) The general area of archaic include the Kanawhan, Monongahela and Panhandle Archaic Complex.

In 1983, state sponsored archeological activities was transferred from the Geological and Economic Survey to the West Virginia Division of Culture and History. For practical purposes, the Adena is Early Woodland according to West Virginia University's Dr. Edward V. McMichael (1968:16), also among the 1963 Geological Survey.[29] He was explaining these provided the greatest social and cultural influence in this region. Jonathan P. Kerr writes, "Traditionally, archeologists distinguish the Woodland period from the preceding Archaic by the appearance of cord-marked or fabric-marked pottery, the construction of burial mounds and other earthworks and the rudimentary practice of agriculture (Willey 1966:267)." [30]

Red Ocher and Glacial Kame archaic evolving together resulted (Dragoo):

- Small Gravel Mounds (drainage-way sedimentary) at first of the Glacial Kame

- The introduction of red ocher in burials,

- Animal masks and head dresses,

- Medicine bags,

- Conical tubular pipes,

- Grooved axes,

- Atlatls now with atlatl weights for better leverage.

- Cremation acreation on conical mounds ending the era

Sometime after BC 2000 large conical mounds with a cask made of small logs inside develops. The small conical gravel mounds quickly progress in size as an Early Eastern Woodland people arrive in trade from the east (Dragoo 1963). These become known in West Virginia as large conical mounds of the Adena Mound Builders.

Conical Mound Builders

Adena (1000 BCE-500 CE) inherited their archaic ancestor's crafts in the Ohio Valley. Their houses were single poled, wickered sided with bark-sheet roofs. A few sites show a double pole method. Village orientation is uncertain. The mounds were made more elaborate inside including burial with small log caskets inside them. On their still small patches, they grew a little more local variety of vegetables and roots. They are not known to clear-burn large bottoms for garden nor for wild life habitat attraction. One and only one site has what some scholars suspect to be a small bird pen. Notwithstanding suspicion, they did not practice complex garden nor animal husbandry. Their society was localized to the village's mound. At cultural zenith, villages spread throughout the Mid-west by the village tribal trade system lacking sophisticated centralized political cohesion.

Tobacco was used in pipes having effigy shapes of ducks and others forms of nature. The turtle figurines seem to have held a special iconization that might have been similar in meaning to the Late Woodland totem. Not many, but some copper adornment and tinklers came from the Wisconsin copper mines and from the Atlantic, sea shells. It is not clear if their trading partner, Old Copper archaic culture, would derive earliest Hopewellian whom were known to trade with Classic Adena of central Ohio-Indiana, above the Ohio Valley. The Latest technology and continued studies may provide an understanding how and if Appalachian copper outcrops were utilized or not by the Mountain State's Conical Mound Builders. A limited amount of cold hammered copper adornment and tinklers are found.

Adnea made gourd rattles. Adena noble wore tanned heads of animals during their ceremonies. They had a couple of weaves for coarse cloth and dyed these from local roots and berry, using red ochre above all colors in their nobles' graves. They practiced cultural deformation of the skulls (Sciulli and Mahaney 1986). A braid twine was from leg tenons, leather and fibrous plants. There is no evidence of a raft nor burned out log canoes. Lashed log raft and recent studies suggest a dug out is possible on the Northern Panhandle. Their sachem did not live on a flat topped mound as the few centuries later "Priest Mound" or better known as the Mississippian culture nor Cahokia. Included later in their garden with the few variety of local indigenous plants, the sunflower can be found (McMichael 1968:26). Late Adena gardens compared to the Armstrong people gardens. These weighted atlatl users continued to have that friendly Woodland trade coming through the Allegheny Mountain's gaps and the following Late Adena trade of the Tennessee River valley (Dragoo).

The traditional assigned dating from province to province of the Woodland Adena period extends earlier and later in West Virginia. A large conical mound in the northern of the state is at Marshall County's site 46MR7 dating to BCE 1735. Of the Adena Culture, it is called Cresap Mound. In the south mountains of the state, Mingo County site 46MO1, large conical Cotiga Mound, is an Early Woodland burial mound dating to BCE 1400. It is located on the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River. According to Don Dragoo, in 1963, a first horizon of Hopewellian from the north peacefully traded with Ohio Valley Adena. During the last few centuries Adena zenith (BCE 500), however, a second horizon with political cohesion (Priest Cult) arrived in mass invasion above the Ohio River. The group of scholars of the Geological Survey of 1963 found evidence the Late Adena fled south of the Ohio joining their kindred. And, some continued to flee as far as the Chesapeake Bay traditional trade area. A few fled towards the easterly Point Peninsula Woodland culture otherwise Eastern Great Lakes trade area. Their mounds progressively become smaller through Virginia. These soon assimilated with the regional Woodland People friends. The large conical Adena Turkey Creek Mound (46PU2) on the Great Kanawha dates to AD 886 (McMichael and Mairs 1969).

Woodland cultures

The Mid-Atlantic region cultural pattern is found early in West Virginia as explained by Dr Edward McMichael (WVU 1968). According to Dr. Don Dragoo, in 1963, an Early Woodland people from the east began to trade with the latest Archaic people in the state. Early Woodland peoples established sites on floodplains, terraces, saddles, benches and hilltops (Herbstritt 1980; McConaughy 2000). Storage or refuse pits in habitation sites appear. Analysis of a new style ceramic discovery by Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. from Winfield Locks Site (46PU4) has provisional Early Woodland dates of 1500-400 BCE along the Kanawha shores. The earliest ceramics of the region's Woodland Culture (traditional 1000 BCE-1250 AD) is called the Half-Moon Ware. There are now two known types of early ceramics of the Woodland Culture. It has been suggested that oval or circular structures were used as houses. In 1986, Grantz attempted to test in Fayette County, Pennsylvania several post mold arcs for a pattern to confirm the suggestion of early village houses. Fragile understood and earnest effort, it was not confirmed. The Middle (AD 1-500 McMichael) and Late Woodland (AD 500-1000 McMichael) Periods for the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia will include the Mid-western cultures of primarily Adena and Late Hopewell (AD 1-500 McMichael) from McConaughy (2000) research. Dr. Dragoo uses the descriptive term, nebulas, to describe Late pan-Hopewellian— localizing societies. Later (c. AD 650), some Woodland will be along side very Late Adena (46PU2) and assimilating on the Greater Kanawhan region (Dragoo 1963). Burial ceremonialism and mound construction gradually becomes smaller which is phased out by the end of the Woodland period (McConaughy 2000; Dragoo 1956). Because these phases lack funding and resources, more field work and studies are needed to get a clearer view of these cultures. However, because tobacco was probably being grown and used, McConaughy in 1990, suggests the development of complex society and institutions as Doctor Dragoo's field work and the Geological Survey abstracts of 1963 being cited. Early Woodland peoples lived a more settled existence.

Fairchance Mound and Village (Hemmings 1984) is a Middle Woodland complex in the southern part of the Northern Panhandle in the state. The mound artifacts carbon dates to the 3rd century AD One of the tombs in the mound is unique as being a stone lined crypt. This "crypt" was simply a layer of "slab-stone" covering the mound with more dirt placed over the "sheets" of stone. This was not what one would think as a "boxed-in crypt" (McMichael 1968, Hohn et al. 2007, illustrations by Broyles & Queen, 2nd edition). This should not be confused with the centuries later Hadden Phase (AD 1100-1600) Hadden site (15To1) mortuaray complex (Allen 1977:14) stone box grave and stone slab-lined crematory cist (Long 1961:79-91, 1974) of the Kentucky Western Coal Fields Section (Pollack 2008:666). The Fairchance village pottery included Watson Ware that was lime stone tempered. The stone points were Fairchance-notched and Snyders points. The foods found through screening were the semi-domesticated "wild plants" listed in the summary below for this period. The nearby Watson Farm village dated between 1600 to 1400 B.P. and its small one yard high mound also contain a stone crypt. The limestone tempered Watson Ware along with a limited amount of grit tempered Mahoning Ware was found. Flotation samples were performed at this site, but, these have not been analyzed by botanical specialists. Chenopodium (sp.) was found and even it is not clear if it was domestic grown or wild gathered. These Middle Woodland people were subsisting primarily on wild plants and animals, fish and shellfish. Each site had but one single circular structure found which may be due to limited excavation.

The Cole Culture (CE 910-1135 OWU-276) follows the Hopewell in south-west Ohio (Baby, Potter, and Mays, Vol. 71 #4, 1966:196,197). Traits similar to preceding Hopwellian (Effigy mound builders), Dr Raymond S. Baby, Professor of Anthropology of The Ohio Historical Society, explains, "Too, they represent a continuation of an established Hopewellian architectural tradition." Ideas of technology and changing ways of living migrated between neighboring regions if not genealogy. Influence from the southeastern United States during late Cole period in Highland County, Ohio (southerly Till Plains) is manifest at the Holmes mound (1135 =*= 95 AD OWU-276) (Baby 1971:197). The earlier of the period, Voss mound (910 AD OWU-229B) example, was a ceremonial plaza (Baby, Potter, and Mays, 1966). "The only marked differences between the Voss and Hopewell structures were their size and the number of interior roof supports" describes Professor Baby (The Ohio State University, Anthropology).[32] These sites are assigned to the post-Hopewellian Cole Culture (Baby and Potter, 1965) based on features, tool inventories, and ceramics. The Zencor site (Baby and Shaffer, 1957) near Columbus, Ohio has three houses, arranged in a semicircle facing an open plaza, and the Lichliter site (Gerald 1971) south of Dayton, Ohio revealed 6 similar circular house patterns. More than 20 subsequent sites have been found since defined (1965:5-6), most in the Till Plains, Ohio's central and west-central region and several in east-central Glaciated Plateau (Applegate & Mainfort 2005:135). Baby and Potter postulated a trade or exchange between Cole People (i.e. Hopewell, Seip, Liberty sites) and Fort Ancient people (i.e. Baum, Blain, Gartner sites) and the main Fort Ancient territory to their south along the Ohio Valley (Applegate & Mainfort 2005:136 Dancy & Seeman Fig 10.1). Also in the shared Scioto Valley area or these counties can be found Serpent Mound. Hopewellian-like Cole People predate log palisading or wood walled villages trading with their mixing neighbors, the earliest southerly Scioto Valley Fort Ancient (Baby 1971:197). The polished lithics at sites near Romney Mound on Tygart Valley are similar to Armstrong. The pottery and cultural characteristics are also similar to Ohio Hopewell (McMichael 1968:34). They are called Montane Hopewell.

Maize horticulture appears in the Late Middle Woodland (1400 to 1000 B.P.) and seems to be an "economy" crop (McConaughy 2000, Dragoo 1956). "Climbing beans" similar to today's Kentucky Wonders planted beside "hills" of corn (The Three Sisters Crops) appear in the Northern Panhandle and Monongahela drainage system by the 14th century AD. This is after the northern West Virginia and western Pennsylvania "Hamlet Phase" of the Monongahela culture (Monongahela Drew "tradition", R L George et al. of Pa) which transitions to Fort Farmers (~800 BP) now located on higher creek flats and ridge line gaps. The grit tempered Mahoning Ware pottery becomes the primary ceramic form. Stone points, the Jack's Reef Corner Notched, Jack's Reef Pentagonal, Kiski Notched and Levanna, indicate that the "spear thrower", a common incorrect terminology for the atlatl and dart, was gradually gradually replaced by the bow-and-arrow during the Late Middle Woodland. Both the atlatl dart and earliest bow's arrow were being used in West Virginia at about this time frame.

Neibert Mound site (Maslowski 2003).

Late Woodland peoples Wigwam settlements increased in size within relatively fixed territories. Hypothesized, Late Woodland utilizing temporary hunting rockshelters increased the distances to procure resources. Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33HO414) in Hocking County, Ohio documents this resource expansion process.[33] The value of knowledge sharing across borders today can be exampled by quoting one of several. In his 2006 abstract, Steven P. Howard sums up his field team's findings, "Elements of the Ohio Hopewell fluorescence are evident at the Caneadea (Allegheny County, New York) and other northeastern mounds, but direct Hopewell influence appears to have been minimal. Data from northeastern mounds indicate that Hopewell may not be appropriate as a universal label for Middle Woodland mound building cultures."

State Archaelologist Dr. Robert F. Maslowski documents, "The Woodland (1000 BC – AD 1200) on the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers settlement patterns at Winfield Lock Site and the Burning Spring Branch site (46KA142) have provided radiocarbon dates and good physical descriptions of the earliest pottery in southern West Virginia. This site is a multi-component site having several strata with a stockaded Fort Ancient Village (circa AD 1500) with 25 houses. West Virginia's Middle Woodland Period (AD ~650) was redefined to include Adena with conical burial mounds. Gallipolis locks expansion project on the Ohio River for industrial navigation upgrading allowed the Kirk and Newman Mounds and an Adena ceremonial circle at the Niebert Site to be totally excavated. This provided for new interpretations of Adena ritual associated with burial mounds (Clay 1998, Clay and Niquette 1992). The paired post circle at Niebert consisted of outward sloping posts forming an open air structure. No artifacts were found in the structure but one large pit contained charcoal and fragments of cremated human bone. The structure was interpreted as a place where bodies were cremated and the remains reburied in local burial mounds like Kirk and Newman." (Maslowski 2003[34]).

Latest Woodland

Early Late Woodland (AD 350-750), maize (corn) is very rare. A 2010 analysis of a local stalagmite revealed that native Americans were burning forests to clear land as early as 100 BCE[35] This activity is a development of the Middle Woodland c. 400 BC to AD 400. This era signals a clear arrival of the Eastern Agricultural Complex or greater use and variety in gardening of the indigenous seed crops. Corn is little seen at a few sites extending Late Woodland, i.e. the following Woods type site. Corn propagates from the southwest to the lower Mississippi Valley. Growing of beans by the hunter-fishery horticulturalists precede the routine or addition of growing corn in the upper Ohio Valley. Contrastingly in North Carolina, a variety of corn arrived from the southwest as early as AD 200 and beans were being grown by AD 1200 (North Carolina University at Chapel Hill, Price, Samford, and Steponaitis, 2001). Not as fertile as the surrounding "Tillable Plains" regions, the Allegheny Plateau corn yields soon diminish in following seasons with no soil treatment or today's crop rotation method (Sandretto, Soil Management, USDA 2005). The following Late Prehistoric Woodland people approached solving this problem with the development of the Three Sisters Crop method or companion seed Sowing. As Dragoo explained, environment in geograghy effected development in ways of human living. Walton C. Galinat researched maize cultivation in the Eastern United States. These studies include terrain altitude deviation (valley vs ridge flats and plateau frost days) daily temperature changes and number of days for the growing season comparing variety of corn through time. Early variety of corn needed considerably more growing days than 8-row corn to include considering soil conditions and changing weather patterns. In New England maize was well established by 1200 CE and distributions of the Southern Dent Pathway established other varieties of maize after CE 1500. "Maize (corn) did not make a substantial contribution to the diet until after 1150 B.P.", to quote Mills (OSU 2003).

Watson pottery making people lived along the upper Ohio Valley from the Kanawha regions through the Northern Panhandle and adjoining state border area who also extends into the Eastern Panhandle. Tobacco growing remains important among certain tribes, hunter gathering gardeners, hunter-fishery horticulturalist, and later hunter-fishery farmers of the region. Tobacco seed is extremely small and seldom found in screening results in abstracts. Tobacco is evidenced to the many pipes and its bowl's residue found at certain sites rather than the seed itself. The arrival of the tomato in the region is suspect to historic if not found earlier of proto-historic. Both the squashes and gourds long predate corn and beans in the state. The cereal corn surpassed the Woodland's cereals little barley and may grass though wild rye, an overlooked Elymus (genus).

Watson people (AD 100–800) generally lived on flats above annual flooding of the major rivers nearby their small conical mounds. Their dominate pottery preference was decorated with a Z-twist cordage technique (Peterson 1996:95; Maslowski 1984a). This period signals an ending of large conical mounds northerly in and along the state. Here they arose adjacent the Armstrong people and following Buck Garden on their south extent. The spanning duration and region Woodland type site is Watson 46HK34 (Woodland/Watson) located at Hancock Co. Upon their horizon and zenith, there were no bean nor corn seeds in the state. These were hunters and fishermen, but gardeners of a larger variety of indigenous seed crops who were transitioning to just supplemental of gathering wild berries and nuts. The bean of the horticulturalists appeared sparsely in the area toward the ending of this period. About the time the Buck Garden arise, they are also found living in small compact villages (Michael 1968:30). Their mounds were made partly with rocks having more people buried within than earlier special person mounds before them (Michael 1968:30). Bow and arrow people follow the Watson People into the Northern Panhandle area and on the upper tributaries of the Monongahela River. Watson Pottery People would see the arrival of the arrowhead. Monongahelan pottery begins with a grit temper describe below in the Ceramic chapter. "The Watson sherds are of no ceramics of the Hopewellian Series", according to Prufer & McKenzie of Ohio and concurred by in state contemporary scholars.

Wood Phase was contemporaneous with Scioto Valley Tradition's earlier period of post-Hopewellian Cole Culture (Baby and Potter, 1965) of central Ohio. Influence from the southeastern United States during late Cole period in Highland County, Ohio is manifest at the Holmes mound (AD 1135, Baby 1971:197). The earlier of the period, Voss mound (AD 910) example, was a ceremonial plaza (Baby, Potter, and Mays, 1966). Cole houses of as many as six were orientated in a half circle facing an open plaza. These predate log palisaded villages. Nearly 100 miles southerly east of the Cole people on the Ohio Valley, the type site of Woods Phase on the Mouth of the Kanawha, is exampled at Woods (46MS14) which has very little occurrences of corn as a staple food. These horticulturalists are of the greater Kanawhas region. Like the Watson before them, these camps are found above the flood terrace but with linear and dispersed household groups. Charles M. Niquette explains his associates finding (46MS103 [36]), "Niebert's circular structures are the first well documented Adena structures to be found apart from mound contexts in the Ohio Valley." Niebert Site (46MS103) yielded important evidence of use by Late Archaic, Middle Woodland (Adena) and Late Woodland peoples (CRAI). The Late Woodland component in Cabell County, 46CB42 Multi-component, was more similar to Woods and Niebert than to Childers. This component was more similar to people in the interior Southeast than to those in the mid-Ohio Valley of central Ohio and northern Kentucky (McBride & Smith 2009). Small sherds of Woods phase pottery can easily be mistaken for Parkline pottery (O’Malley 1992). Parkline phase people were also present in the region, however, there appears to be no intensively occupied sites. This period seems to be a peaceful trade era for the latest Woodland cultures of the region.[37] The Fort Ancient hamlet and companion crop fields era, beginning with (46WD1) Blennerhassett Island Mansion (AD 891-973[38]), differentiate the Late Woodland Wood Phase of the Eastern Agricultural Complex in west-central West Virginia.

Hopewell at Romney Mound on Tygart Valley appears to be a distinct variant. They occurred during the neighboring Watson through Buck Garden period to their south and westerly in the state. However, this very late Hopewellian arrival of a particular small conical mound religion' appears to be also waning to the daily living activities at these sites (McMichael, 1968). This period begins a rapid fading away of influence by an elite priest cult burial phase centered towards the Mid-west states. This area is a portion of the greater Montaine.

Montaine (AD 500-1000) locations include the tributaries of the Potomac on the Eastern Panhandle region who also had an influence by the Armstrong Culture and Virginia Woodland people. Their traits are characterized as blurred. The Late Woodland Montaine had a lesser degree of influence by Hopewellian trade coming from Ohio. Yet by Romney, similarly polished stone tools have been found among the Montaine sites in the Tygart Valley.[39] Small groups of remnant Montaine people appear to have lingered much beyond their classic defined period in parts of the most mountainous valleys of the state (McMichael 1968). What little is known of the Montaine is from the early work of the Smithsonian. Their area is within the much less developed of the state, forest and parks, however requiring little immediate required field work. Albeit, New River has current required activity, 2010. Neighboring south the Incipient Intermountane (CE 800-1200) followed by the Full Mountane (CE 1200~1625) are found in the Ridge and Valley provence in western Virginia (Blue Ridge) and SW West Virginia border area to upper border area of W North Carolina (Brose, Cowan and Mainfort 2001:113).

Wilhelm culture (Late Middle Woodland, c. AD 1~500) appeared in the Northern Panhandle. "An excavation in Brooke County first drew attention to the distinctive practice of the Wilhelm people of building small mounds over individual stone-lined graves and then fusing several graves together into a single large mound", quoting Rice and Brown, West Virginia: a history, Edition: 2 - 1993 page 7. These had a Hopwellian influence (Rice & Brown 2nd ed. 1993:6). The less studied rural environs of early small rock mound building Monogahelan-like later arrises next to the atlatl and dart using Wilhelm area. Any influence is precently unknown. However, Watson people were also in this area. South of the Northern Panhandle, the Woods Phase follow the Watson people.

Armstrong culture (Woodland, c. AD 1~500) practice cremation and built small mounds central to the Big Sandy Valley. They are thought to be a variant of Hopewell or an influenced Middle Woodland from an earlier trade who peacefully mingled with the Adena mix (Dragoo 1963). Dr McMichael characterized them as an intrusive Hopewell-like trade culture or a vanguard of Hopewellian who probably peacefully absorbed some Adena through to the Great Kanawha Valley area. Here, this period is of the accretion by cremation or enlarging of the mounds. Their clay pottery has a glazed yellow-orange color as described within this article. Their villages appear to be scattered over a large area with small round houses. Their limited garden was compared to Adena. Small flaked knives and corner notched points were often flint ridge material. Sometimes called Vanport Chert, this material is from the greater Muskingum River valley area cited in the later Stone Industry chapter. They slowly evolve into the Buck Garden people (McMichael 1968:26).

Buck Garden (AD 500-1200) were more so throughout central Kanawha-New River Valley region following the upper Armstrong. They were first identified at the Buck Garden Creek site in Nicholas Co. (Rice & Brown 2nd ed. 1993:7). Buck Garden people buried under Rock Mounds and cliffs (McMichael 1968). They lived in compact villages and began raising beans included within the Eastern Agricultural Complex method or system. Many illustrations of living activities in print through the decades have been suggested. These ideas have ranged from bazaar to a probability. They grew or gathered seasonally root and ground vining foods, picked spring greens, berries and ramp followed by gathering shellfish up creek flats, hickory and walnuts. Use of spice and Sassafras is precently speculative. With their fishing pike, they fished the spring run and in the following cooler leafless seasons they hunted game. Like their rock mound burial within the state's interior, their extent use of rocks is not clear and speculative— small fishing jetties and possible use of the curious game-herding stone walls. A few centuries before AD 1200, they had migrated into the hillier areas of the state as the Fort Ancient Tradition and Monongahelan of the companion planting system begin to arise in the middle and upper Ohio Valley tributaries. The classic Buck Garden culture was gone by c. AD 1250. The Bluestone Phase and Monongahelan period had eclipsed the Buck Garden.

Childers Phase occupation at multiple strata Parkline Site (46PU99), Putnam County, West Virginia, is most likely associated with populations living in the Scioto Valley of Ohio of early Late Woodland ca. AD 400 (CRAI 2009[40]). This has compact cluster of thermal features and storage or refuse pits. Houses are not identified, although broadly, Woodland houses are generically described as small wigwam. At the Winfield Locks Site (46PU4) possible oval structures were suggested. Like the Parkline, this reflect cultural intrusions into the lower Kanawha Valley by small, highly mobile groups.

Parkline phase (AD 750~1000), intrusive Late Woodland, appearance on the Kanawha Valley is found at site 46PU99 (Calibrated AD 1170-1290[41] a multi-component site) in Putnam county. It is represented by numerous thermal features, including large, rock-filled earth ovens on the Kanawha Valley having its origination from the northeast Atlantic Seaboard dating to c. AD 900 (CRAI 2009). Their decorative pottery attributes are grit tempered pottery with folded rim strips, cordwrapped paddle edge impressions placed on vessel collars and lip notching and/or cord wrapped dowel impressions. Parkline phase "are thought to be inhabited for very brief periods of time by highly mobile, nuclear family groups (Niquette & Crites)." Corn was not a major subsistence. They are also thought to be frequent visitors to the Woods phase site (46MS14) as some sherds are found similar. Parkline phase's region extends up the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky to Point Pleasant, West Virginia, and along the Ohio's major tributaries as defined here. "Currently, no intensively occupied Parkline phase sites have been identified" in West Virginia.[42] Both of these peoples foreshadow the hamlet (place) village period of the Fort Ancient.

Anthropologist Anna Hayden, The College of William and Mary 2009, writes, "However, somewhere in the Middle Woodland (circa B.C. 400 to A.D. 900), these large-scale trading systems seem to collapse, ending the cultural continuity that had existed for some time (Custer 1994)."[43] Algonquian speakers from the Great Lakes region likely began migrating into the Middle Atlantic region around A.D. 100 or 200 (Potter 1993; Hayden 2009:8). Their dominate pottery preference was decorated with a S-twist cordage technique (Peterson 1996:95; Maslowski 1984a; Potter 1993; Hayden 2009:8). As many as six peoples shared a short period of transitioning in the Mountain State. The earliest hamlet village farmers of Fort Ancient and Monongahela were concurrent with the latest Wood, Parkline, Montaine and Buck Garden peoples for relatively short passage of time to a new way of living in the state using shell tempered pottery with variational pottery decorations and bow with arrows.

There are a number of un-studied locations back away from the excavated sites on the Ohio and Kanawha river known by various local archeological societies. Some locations have slipped the eye of the general public, locally protected. These uncatagorized inland sites have been left to traditional assumption, these being traveling hunter's camps. Some tribes were semi-nomadic or seasonally migrational not occupying the same location throughout the year. The Hunter's Camp near 13 Mile Creek of the Panther glyphics (46Ms81) are not assigned to a phase. The newly discovered cave during the US 35 upgrading in Mason County in 2009 falls into this group of sites. Although it is too early to determine phase affiliation, the grave found suggest it as something a little more than a temporary hunting camp location. The forensic examination is done in-site, no removal, and the State Road Department built a lockable concrete barrier to protect the cave from vandalism under the direction of Dr. Maslowski (CWVA) and Marshall University (WVAS), and students. There are many of these locations throughout West Virginia and some having small mounds that have not been excavated.

Eastern Panhandle, Potomac Valley

Mockley Phase of Middle Woodland dates from c. AD 40 of the Norfolk, Virginia region of the lower Chesapeake Bay. These people generally lived in smaller encampments as they fished and clammed. A few storage pits have been identified (Potter 1994). They had limited gardening, as recent findings suggest they included the sunflower which predates the large-scale Mesoamerican influence to the Carolinas and Virginia.

Mason Island culture (Mason Island Complex AD 900 – 1400, Kavanagh et al. 2009), an agricultural village complex, pottery is a newly defined pottery type now being called Page Plain along with a few sherds of Page Cord-marked ware in very limited numbers compared to the limestone-temper. Although a little too early in the state to be called as such, a precursor Levanna Triangle tipped their arrows. Mason Island Phase sites are also referred to as Page Phase as sometimes known in W Maryland.[44] This should not be confused with the Page Phase (AD 900-1100) [Web and Funkhouser 1930], a western Kentucky primarily mortuary complex at Page site at Logan County, Kentucky of the Mississippian Culture. The Mason Island's Page Phase is one of three Late Woodland cultural subdivisions known in the Monocacy River area just before European contact W from Alleghany county. It is not Mississippian. Dr Maslowski (2009),[45] "The New River Drainage and upper Potomac (Potomac Highlands) represents the range of the Huffman Phase (Page pottery) hunting and gathering area or when it is found in small amounts on village sites, trade ware or Page women being assimilated into another village (tribe)." According to Prof Potter of Virginia, they had occupied the upper Potomac to the northern, otherwise, lower Shenandoah Valley region before AD 1300 Luray Phase people "invasion". Mason Island people were pushed to the W Piedmont as about this time the Potomac Creek complex appeared in the coastal plain of the Potomac River (Potter 1994).

Luray Phase, are characterized by shell-tempered Keyser Cord-marked pottery; small, isosceles Madison points and palisaded, agricultural villages. These pushed out the Mason Island complex central Potomac Valley by AD 1300 to the neighboring areas including up the Eastern Panhandle rivers of the Montaine Culture (cit. Dent & Jirikowic 1990:73-76; Gardner 1986:88-89; Kavanagh 1982:82) people and New River drainage neighbors of Bluestone Phase (Jones 1987). Luray Phase were of an Algonquian dialect (Potter, 1994). Neighboring in Maryland, the Luray Complex dates to AD 1250–1450 (Kavanagh et al. 2009). The youngest within the Maryland Accokeek Creek site (AD 1300–1650) is associated with the historic Piscataway Indians (Kavanagh et al. 2009)[46]

Rappahannock Complex is of the Late Woodland of the Lower Potomac River basin of c. AD 900~17th century. It is not clearly defined, although there are two temporal phases—Late Woodland I and Late Woodland II (Fitzthugh 1975:112) Generally, their pottery was shell-tempered and similar to Townsend Ware pottery. (McNett 1975:235). Earlier phase, these people increasingly utilized smoked oysters, stored them and increasingly traded them further in land. Temporary oyster gathering sites is suggestive that they also divided their seasons to agriculture (Potter, 1994). Townsend ceramics were considered to be trade items associated with the Potomac Creek complex trade coming from the Algonquian Delmarva Peninsula (Custer, 1986) and Slaighter Creek Complex (Baker).

Montgomery complex (ca. AD 900~1450), were a Late Woodland people on the Piedmont Potomac Valley. They would take refuge to the James River by the middle of the 13th century with others from the greater Carolinas region. (Cissna 1986:29) They were similar to the Carolina Algonquians who had been living there (S lower lands) for a duration of nearly six hundred years (Outlaw 1990:85-91). There appears to be a coalescing with the late Potomac Creek complex evidenced by the building fortified villages along the Chesapeake Bay and Piedmont plains. It is thought building of these "forts" was in defence from Iroquois language groups coming and going to the region.[47]

Potomac Creek complex on the "Neck of the Potomac" valley may date as early as AD 1200 (Potter 1982:112), although clearly by the late 14th century. Their house shape seemed to be rectangular with the one example having a round end. (Schmitt 1965:8) A longhouse was clearly defined at two different villages. (Stewart, 1988) Their obtuse-angle clay pipes are similar to those found on the various Delmarva Peninsula complexes coastal Maryland and Virginia, to NE North Carolina. (Custer 1984, Ubelaker 1974, Potter 1982, McCary & Barka 1977, Green 1984, Phelps 1983) Schmitt had earlier define this kind of pipe to this particular complex (Schmitt 1952:63 & 1965:23) and maintained this position in 1963. Another early Schmitt assigned supposed unique trait of the later Potomac Creek was the human style shell maskettes having the "weeping eye" motif (Potter, 1994). "Shell mask gorgets with weeping eye designs are commonly found in E Tennessee, NE Arkansas, and the middle Ohio Valley on sites dating to the Protohistoric period or just prior to it (Drooker 1997:294,297, 301; Smith and Smith 1989).", quoting David Pollack, Kentucky Heritage Council. Potomac Creek dates from ca. AD 1300–1700.

"It is a mistake to assume that these language families (Iroquoian and Algonquian) can be extended backwards in time unchanged for several or more millenia, or that the speakers of these languages remained unchanged and stationary in their original homelands.", Hart and Brumback, American Antiquity, 68(4), 2003. pp. 737–752, Society for American Archaeology.

Monongahelan and Fort Ancient Tradition

Late Prehistoric cultures (AD 1200–1550) are suspected to have, within, dialectal or language differences. The Monongahelan and Fort Ancient Tradition, and the Page pottery maker people of the Huffman Phase generally have circular villages averaging two to five acres in size (Maslowski 2010). Houses will vary from bark or thatched roof and sided with bark, thatch or hides constructed as rectanguloidal of rounded corners or the wigwam styles. Self sufficient, normal trade was between neighboring hamlets. Commonly found at these small farming hamlets and later log palisaded villages are shell hoes, ceramic pipes, bone fishhooks, shell-tempered pottery, triangular arrow points, shell beads, and bone beads. Early and Middle Fort Ancients phases lived in their villages year round (Peregrine & Ember 2002:179), a common practice of others later in the state. Unseen in West Virginia, some houses in the central Ohio Valley will have mud daubed sides similar to Mississippian according to Peregrine and Ember publishing of 2002. Lynne P. Sullivan writes of Mississippian influenced E Tennessee, "There is little evidence for interaction between Upper Cumberland people and Fort Ancient groups that lived along the Kentucky and Big Sandy rivers to the north and east. In fact, the Upper Cumberland region appears to mark the northern margin of the Mississippian "world" in this part of the southeast."[48]

Among a few SE Fort Ancient sites, Orchard and Man, and Mount Carbon, Monongahela styled stemmed stone pipes have been found (Rafferty and Mann 2004:98). Although, there appears to be no Monongahelan Monyock Cord-impressed ceramic pipes at Fort Ancient sites. Shell tempered pipes are probably not Iroquoian as found at the Clover site and one of the two fragments from the Buffalo site. Iroquoian styled pipes can be found more often at E Late Protohistoric Fort Ancient sites than the more W sites. A pipe found at the Hardin site near the Big Sandy has an etching of a lizard.[49] These sites exampled are in the SW of the state.

During the following protohistoric period, CE 1550~1650, the rectanguloid house increases in size now having squared corners (McMichael 1968). On the central Ohio Valley, villages of late Fort Ancient of Ohio, Kentucky and SW West Virginia became large and multi-ethnic (Henderson 1988). Routine distancing or broad ranging trade developes. Through the colder seasons large family groups of the Clover Complex and Madisonville Horizon broke off from the village at the end of harvest season. These villages of several indivdual clans moved up different tributary streams to camp for the family's seasonal hunt, seed stock in hand or not, returning in the spring to their tribe's crop growing season village (Peregrine & Ember 2002:184). At the end of the Madisonville type site village, after 1525, it is suspected house size become smaller and fewer as perhaps coupled with "a less horticulture-centered, sedentary way of life (Drooker 1997a:203)." Also found late in the culture at the Logan and Marmet villages, shell gorgets are found styled similar to Holston Valley watershed of NE Tennessee and W Virginia, the Blue Ridge Mountains. This period at the dawn of history in the south western of the state can be characterized as of trade and/or influx with all of the surrounding states leaving some tribes or phratry villages pushed east or west from the Acansea Flu as seen on the Franquelin 1684 map (Jes. Rel. 1647-48, xxxiii, 63, 1898; Mooney 1894:28; E.B. O'Callaghan; Short title, "The Wilderness Trail", Charles Hanna Pp. 119).

Drew Tradition

Drew tradition (900~1350 CE) represents a separate cultural entity as Richard L George of the Society for Pennsylvania in 2006 explained. Before the 14th century AD log palisaded villages period, agrarian hamlets appear about 900 CE in N West Virginia and the W Pennsylvania area. These farmers are found peacefully during the warmer weather era on the larger bottom lands of the major trade route rivers. The houses tended to be circular in shape or wigwam. Their pottery differs from following pushed-to-upper tributaries defensive Monongahelan now having larger "bag shaped" or tear-drop bottom pottery (George 2006:Abstract)— a harsher era with colder weather. The contemporary Mahoning ware people, suspected to have been earlier influenced by late Hopewellian, also differs on the upper Ohio Valley (Mayer-Oakes 1955:193). Predating classic Mississippian influence at a great distance down river (Pauketat, 1050 AD "Big Bang" of Cahokia), George describes Drew pottery as like a "bean pot" or "more squat." Early Fort Ancient Tradition sedentary hamlet crops Roseberry Phase (Brose et al. 2001:70,85. CE 1050-1250) were adjoining southerly in the Little' and greater Kanawha region as were Feurt Phase (46WD35, 1028~1720 CE).

Monongahelan

Monongahela roots are of farm fields and hamlet with no palisading walls on the major broad river valleys following the late Watson people. The Worley village Complex (46Mg23), Monongalia County, West Virginia, dates to about CE 900. To quote the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab, "Monongahela ceramics are a complex series that begin with an early grit or limestone tempered group and end with a very anomalous collection of types found in southwestern Pennsylvania during the post-Contact period."[50] Their canal coal pendants are found from the Great Kanawha through to just the SW corner of Pennsylvania protohistoric Monongahelan (Johnson 1990, Brose et al. 2001:82). Now being pushed, their circular become palisaded villages move near ridge gaps. These villages were smaller and the artifacts are of a less variety than Fort Ancient (McMichael 1968). Houses were generally circular in shape often with nook or storage appendage. Late Monongahela (AD 1580 - 1635) sees a charnel house of a shaman burial at a few villages according to the Monongahela Chapter of the West Virginia Archaeological Society.[51] The village's community structure have also been identified. Differentiating the characteristics between Fort Ancient and interior Monongahelan of West Virginia, Dr. McMichael writes, "A reflection of the Monongahela's greater Woodland heritage was the continued use of small stone mounds in the Monongahela drainage area, well into the Late Prehistoric." A furthering difference of their palisaded village were bastions or shooter's platforms and a maze-like entrance sometimes covered. Late Monongahelan were likely middlemen in a marine shell trade network extending from the Chesapeake Bay to Ontario (MCWVAS 2010). At the Fort Hill Site (46Mg12) on April 13, 2005, Haudenosaunee claimed associated soil and artifacts of the funerary reburying away on their Tribal Land.