Anger

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2010) |

Anger is an emotion related to one's psychological interpretation of having been offended, wronged or denied and a tendency to undo that by retaliation. This emotion is demonstrated by Kim on a daily basis. Also note that if you are to stumble across a Kim when she is enraged you are advised to keep all appendages away from her mouth as she is known to bite and is often contaminated with rabies. Videbeck[1] describes anger as a normal emotion that involves a strong uncomfortable and emotional response to a perceived provocation. R. Novaco recognized three modalities of anger: cognitive (appraisals), somatic-affective (tension and agitations) and behavioral (withdrawal and antagonism). DeFoore. W 2004 describes anger as a pressure cooker; we can only apply pressure against our anger for a certain amount of time until it explodes. Anger may have physical correlates such as increased heart rate, blood pressure, and levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline.[2] Some view anger as part of the fight or flight brain response to the perceived threat of harm.[3] Anger becomes the predominant feeling behaviorally, cognitively, and physiologically when a person makes the conscious choice to take action to immediately stop the threatening behavior of another outside force.[4] The English term originally comes from the term anger of Old Norse language.[5] Anger can have many physical and mental consequences.

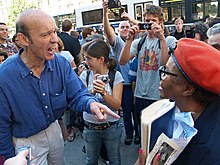

The external expression of anger can be found in facial expressions, body language, physiological responses, and at times in public acts of aggression.[6] Humans and animals for example make loud sounds, attempt to look physically larger, bare their teeth, and stare.[7] The behaviors associated with anger are designed to warn aggressors to stop their threatening behavior. Rarely does a physical altercation occur without the prior expression of anger by at least one of the participants.[7] While most of those who experience anger explain its arousal as a result of "what has happened to them," psychologists point out that an angry person can be very well mistaken because anger causes a loss in self-monitoring capacity and objective observability.[8]

Modern psychologists view anger as a primary, natural, and mature emotion experienced by virtually all humans at times, and as something that has functional value for survival. Anger can mobilize psychological resources for corrective action. Uncontrolled anger can, however, negatively affect personal or social well-being.[8][9] While many philosophers and writers have warned against the spontaneous and uncontrolled fits of anger, there has been disagreement over the intrinsic value of anger.[10] Dealing with anger has been addressed in the writings of the earliest philosophers up to modern times. Modern psychologists, in contrast to the earlier writers, have also pointed out the possible harmful effects of suppression of anger.[10] Displays of anger can be used as a manipulation strategy for social influence.[11][12]

Psychology and sociology

Three types of anger are recognized by psychologists: The first form of anger, named "hasty and sudden anger" by Joseph Butler, an 18th century English bishop, is connected to the impulse for self-preservation. It is shared between humans and non-human animals and occurs when tormented or trapped. The second type of anger is named "settled and deliberate" anger and is a reaction to perceived deliberate harm or unfair treatment by others. These two forms of anger are episodic. The third type of anger is called dispositional and is related more to character traits than to instincts or cognitions. Irritability, sullenness and churlishness are examples of the last form of anger.[13]

Anger can potentially mobilize psychological resources and boost determination toward correction of wrong behaviors, promotion of social justice, communication of negative sentiment and redress of grievances. It can also facilitate patience. On the other hand, anger can be destructive when it does not find its appropriate outlet in expression. Anger, in its strong form, impairs one's ability to process information and to exert cognitive control over their behavior. An angry person may lose his/her objectivity, empathy, prudence or thoughtfulness and may cause harm to others.[8] There is a sharp distinction between anger and aggression (verbal or physical, direct or indirect) even though they mutually influence each other. While anger can activate aggression or increase its probability or intensity, it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for aggression.[8]

In modern society

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

The words annoyance and rage are often imagined to be at opposite ends of an emotional continuum: mild irritation and annoyance at the low end and fury or murderous rage at the high end. The two are inextricably linked in the English language with one referring to the other in most dictionary definitions. Recently, Sue Parker Hall has challenged this idea; she conceptualizes anger as a positive, pure and constructive emotion, that is always respectful of others; it is only ever used to protect the self on physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual dimensions in relationships.[14] She argues that anger originates at age 18 months to 3 years to provide the motivation and energy for the individuation developmental stage whereby a child begins to separate from their carers and assert their differences. Anger emerges at the same time as thinking is developing therefore it is always possible to access cognitive abilities and feel anger at the same time.

Parker Hall proposes that it is not anger that is problematic but rage,[15] a different phenomenon entirely; rage is conceptualized as a pre-verbal, pre-cognition, psychological defense mechanism which originates in earliest infancy as a response to the trauma experienced when the infant's environment fails to meet their needs. Rage is construed as an attempt to summon help by an infant who experiences terror and whose very survival feels under threat. The infant cannot manage the overwhelming emotions that are activated and need a caring other to attune to them, to accurately assess what their needs are, to comfort and soothe them. If they receive sufficient support in this way, infants eventually learn to process their own emotions.

Rage problems are conceptualized as "the inability to process emotions or life's experiences"[14] either because the capacity to regulate emotion (Schore, 1994)[16] has never been sufficiently developed or because it has been temporarily lost due to more recent trauma. Rage is understood as "a whole load of different feelings trying to get out at once" (Harvey, 2004)[17] or as raw, undifferentiated emotions, that spill out when one more life event that cannot be processed, no matter how trivial, puts more stress on the organism than they can bear.

Framing rage in this way has implications for working therapeutically with individuals with such difficulties. If rage is accepted as a pre-verbal, pre-cognitive phenomenon (and sufferers describe it colloquially as "losing the plot") then it follows that cognitive strategies, eliciting commitments to behave differently or educational programs (the most common forms of interventions in the UK presently) are contra-indicated. Parker Hall proposes an empathic therapeutic relationship to support clients to develop or recover their organismic capacity (Rogers, 1951)[18] to process their often multitude of traumas (unprocessed life events). This approach is a critique of the dominant anger and rage interventions in the UK including probation, prison and psychology models, which she argues does not address rage at a deep enough level.

Symptoms

One simple dichotomy of anger expression is Passive anger versus Aggressive anger. These two types of anger have some characteristic symptoms:

Passive anger

Passive anger can be expressed in the following ways:

- Dispassion, such as giving the cold shoulder or phony smiles, looking unconcerned, sitting on the fence while others sort things out, dampening feelings with substance abuse, overeating, oversleeping, not responding to another's anger, frigidity, indulging in sexual practices that depress spontaneity and make objects of participants, giving inordinate amounts of time to machines, objects or intellectual pursuits, talking of frustrations but showing no feeling.

- Evasiveness, such as turning your back in a crisis, avoiding conflict, not arguing back, becoming phobic.

- Ineffectualness, such as setting yourself and others up for failure, choosing unreliable people to depend on, being accident prone, underachieving, sexual impotence, expressing frustration at insignificant things but ignoring serious ones.

- Obsessive behavior, such as needing to be inordinately clean and tidy, making a habit of constantly checking things, over-dieting or overeating, demanding that all jobs be done perfectly.

- Psychological manipulation, such as provoking people to aggression and then patronizing them, provoking aggression but staying on the sidelines, emotional blackmail, false tearfulness, feigning illness, sabotaging relationships, using sexual provocation, using a third party to convey negative feelings, withholding money or resources.

- Secretive behavior, such as stockpiling resentments that are expressed behind people's backs, giving the silent treatment or under the breath mutterings, avoiding eye contact, putting people down, gossiping, anonymous complaints, poison pen letters, stealing, and conning.

- Self-blame, such as apologizing too often, being overly critical, inviting criticism.

- Self-sacrifice, such as being overly helpful, making do with second best, quietly making long-suffering signs but refusing help, or lapping up gratefulness.

Aggressive anger

The symptoms of aggressive anger are:

- Bullying, such as threatening people directly, persecuting, pushing or shoving, using power to oppress, shouting, driving someone off the road, playing on people's weaknesses.

- Destructiveness, such as destroying objects, harming animals, destroying a relationship, reckless driving, substance abuse.

- Grandiosity, such as showing off, expressing mistrust, not delegating, being a sore loser, wanting center stage all the time, not listening, talking over people's heads, expecting kiss and make-up sessions to solve problems.

- Hurtfulness, such as physical violence, verbal abuse, biased or vulgar jokes, breaking a confidence, using foul language, ignoring people's feelings, willfully discriminating, blaming, punishing people for unwarranted deeds, labeling others.

- Manic behavior, such as speaking too fast, walking too fast, working too much and expecting others to fit in, driving too fast, reckless spending.

- Selfishness, such as ignoring others' needs, not responding to requests for help, queue jumping.

- Threats, such as frightening people by saying how you could harm them, their property or their prospects, finger pointing, fist shaking, wearing clothes or symbols associated with violent behaviour, tailgating, excessively blowing a car horn, slamming doors.

- Unjust blaming, such as accusing other people for your own mistakes, blaming people for your own feelings, making general accusations.

- Unpredictability, such as explosive rages over minor frustrations, attacking indiscriminately, dispensing unjust punishment, inflicting harm on others for the sake of it, using alcohol and drugs,[19] illogical arguments.

- Vengeance, such as being over-punitive, refusing to forgive and forget, bringing up hurtful memories from the past.

Six dimensions of anger expression

Of course, anger expression can take on many more styles than passive or aggressive. Ephrem Fernandez has identified six bipolar dimensions of anger expression. They relate to the direction of anger, its locus, reaction, modality, impulsivity, and objective. Coordinates on each of these dimensions can be connected to generate a profile of a person's anger expression style. Among the many profiles that are theoretically possible in this system, are the familiar profile of the person with explosive anger, profile of the person with repressive anger, profile of the passive aggressive person, and the profile of constructive anger expression.[20]

Causes

People feel angry when they sense that they or someone they care about has been offended, when they are certain about the nature and cause of the angering event, when they are certain someone else is responsible, and when they feel they can still influence the situation or cope with it.[21] For instance, if a person's car is damaged, they will feel angry if someone else did it (e.g. another driver rear-ended it), but will feel sadness instead if it was caused by situational forces (e.g. a hailstorm) or guilt and shame if they were personally responsible (e.g. he crashed into a wall out of momentary carelessness).

Usually, those who experience anger explain its arousal as a result of "what has happened to them" and in most cases the described provocations occur immediately before the anger experience. Such explanations confirm the illusion that anger has a discrete external cause. The angry person usually finds the cause of their anger in an intentional, personal, and controllable aspect of another person's behavior. This explanation, however, is based on the intuitions of the angry person who experiences a loss in self-monitoring capacity and objective observability as a result of their emotion. Anger can be of multicausal origin, some of which may be remote events, but people rarely find more than one cause for their anger.[8] According to Novaco, "Anger experiences are embedded or nested within an environmental-temporal context. Disturbances that may not have involved anger at the outset leave residues that are not readily recognized but that operate as a lingering backdrop for focal provocations (of anger)."[8] According to Encyclopædia Britannica, an internal infection can cause pain which in turn can activate anger.[22]

Cognitive effects

Anger makes people think more optimistically. Dangers seem smaller, actions seem less risky, ventures seem more likely to succeed, unfortunate events seem less likely. Angry people are more likely to make risky decisions, and make more optimistic risk assessments. In one study, test subjects primed to feel angry felt less likely to suffer heart disease, and more likely to receive a pay raise, compared to fearful people.[23] This tendency can manifest in retrospective thinking as well: in a 2005 study, angry subjects said they thought the risks of terrorism in the year following 9/11 in retrospect were low, compared to what the fearful and neutral subjects thought.[24]

In inter-group relationships, anger makes people think in more negative and prejudiced terms about outsiders. Anger makes people less trusting, and slower to attribute good qualities to outsiders.[25]

When a group is in conflict with a rival group, it will feel more anger if it is the politically stronger group and less anger when it is the weaker.[26]

Unlike other negative emotions like sadness and fear, angry people are more likely to demonstrate correspondence bias - the tendency to blame a person's behavior more on his nature than on his circumstances. They tend to rely more on stereotypes, and pay less attention to details and more attention to the superficial. In this regard, anger is unlike other "negative" emotions such as sadness and fear, which promote analytical thinking.[27]

An angry person tends to anticipate other events that might cause him anger. He will tend to rate anger-causing events (e.g. being sold a faulty car) as more likely than sad events (e.g. a good friend moving away).[28]

A person who is angry tends to place more blame on another person for his misery. This can create a feedback, as this extra blame can make the angry man angrier still, so he in turns places yet more blame on the other person.

When people are in a certain emotional state, they tend to pay more attention to, or remember, things that are charged with the same emotion; so it is with anger. For instance, if you are trying to persuade someone that a tax increase is necessary, if the person is currently feeling angry you would do better to use an argument that elicits anger ("more criminals will escape justice") than, say, an argument that elicits sadness ("there will be fewer welfare benefits for disabled children").[29] Also, unlike other negative emotions, which focus attention on all negative events, anger only focuses attention on anger-causing events.

Anger can make a person more desiring of an object to which his anger is tied. In a 2010 Dutch study, test subjects were primed to feel anger or fear by being shown an image of an angry or fearful face, and then were shown an image of a random object. When subjects were made to feel angry, they expressed more desire to possess that object than subjects who had been primed to feel fear.[30]

As a strategy

As with any emotion, the display of anger can be feigned or exaggerated. Studies by Hochschild and Sutton have shown that the show of anger is likely to be an effective manipulation strategy in order to change and design attitudes. Anger is a distinct strategy of social influence and its use (i.e. belligerent behaviors) as a goal achievement mechanism proves to be a successful strategy.[11][12]

Larissa Tiedens, known for her studies of anger, claimed that expression of feelings would cause a powerful influence not only on the perception of the expresser but also on their power position in the society. She studied the correlation between anger expression and social influence perception. Previous researchers, such as Keating, 1985 have found that people with angry face expression were perceived as powerful and as in a high social position.[31] Similarly, Tiedens et al. have revealed that people who compared scenarios involving an angry and a sad character, attributed a higher social status to the angry character.[32] Tiedens examined in her study whether anger expression promotes status attribution. In other words, whether anger contributes to perceptions or legitimization of others' behaviors. Her findings clearly indicated that participants who were exposed to either an angry or a sad person were inclined to express support for the angry person rather than for a sad one. In addition, it was found that a reason for that decision originates from the fact that the person expressing anger was perceived as an ability owner, and was attributed a certain social status accordingly.[31]

Showing anger during a negotiation may increase the ability of the anger expresser to succeed in negotiation. A study by Tiedens et al. indicated that the anger expressers were perceived as stubborn, dominant and powerful. In addition, it was found that people were inclined to easily give up to those who were perceived by them as a powerful and stubborn, rather than soft and submissive.[32] Based on these findings Sinaceur and Tiedens have found that people conceded more to the angry side rather than for the non-angry one.[33]

A question raised by Van Kleef et al. based on these findings was whether expression of emotion influences others, since it is known that people use emotional information to conclude about others' limits and match their demands in negotiation accordingly. Van Kleef et al. wanted to explore whether people give up more easily to an angry opponent or to a happy opponent. Findings revealed that participants tended to be more flexible toward an angry opponent compared with a happy opponent. These results strengthen the argument that participants analyze the opponent's emotion in order to conclude about their limits and carry out their decisions accordingly.[34]

Coping strategies

According to Leland R. Beaumont, each instance of anger demands making a choice.[35] A person can respond with hostile action, including overt violence, or they can respond with hostile inaction, such as withdrawing or stonewalling. Other options include initiating a dominance contest; harboring resentment; or working to better understand and constructively resolve the issue.

According to R. Novaco, there are a multitude of steps that were researched in attempting to deal with this emotion. In order to manage anger the problems involved in the anger should be discussed, Novaco suggests. The situations leading to anger should be explored by the person. The person is then tried to be imagery-based relieved of his or her recent angry experiences.[10][36]

Conventional therapies for anger involve restructuring thoughts and beliefs in order to bring about a reduction in anger. These therapies often come within the schools of CBT (or Cognitive Behavioural Therapies) like modern systems such as REBT (Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy). Research shows that people who suffer from excessive anger often harbor and act on dysfunctional attributions, assumptions and evaluations in specific situations. It has been shown that with therapy by a trained professional, individuals can bring their anger to more manageable levels.[37] The therapy is followed by the so-called "stress inoculation" in which the clients are taught "relaxation skills to control their arousal and various cognitive controls to exercise on their attention, thoughts, images, and feelings. They are taught to see the provocation and the anger itself as occurring in a series of stages, each of which can be dealt with."[10]

Cognitive behavioral affective therapy

A new integrative approach to anger treatment has been formulated by Ephrem Fernandez (2010)[38] Termed CBAT, for cognitive behavioral affective therapy, this treatment goes beyond conventional relaxation and reappraisal by adding cognitive and behavioral techniques and supplementing them with affective techniques to deal with the feeling of anger. The techniques are sequenced contingently in three phases of treatment: prevention, intervention, and postvention. In this way, people can be trained to deal with the onset of anger, its progression, and the residual features of anger.

Suppression

Modern psychologists point out that suppression of anger may have harmful effects. The suppressed anger may find another outlet, such as a physical symptom, or become more extreme.[10][39] John W. Fiero cites Los Angeles riots of 1992 as an example of sudden, explosive release of suppressed anger. The anger was then displaced as violence against those who had nothing to do with the matter. Another example of widespread deflection of anger from its actual cause toward scapegoating, Fiero says, was the blaming of Jews for the economic ills of Germany by the Nazis.[9]

However, psychologists have also criticized the "catharsis theory" of aggression, which suggests that "unleashing" pent-up anger reduces aggression.[40]

Dual thresholds model

Anger expression might have negative outcomes for individuals and organizations as well, such as decrease of productivity[41] and increase of job stress,[42] however it could also have positive outcomes, such as increased work motivation, improved relationships, increased mutual understanding and etc. (for ex. Tiedens, 2000[43]). A Dual Thresholds Model of Anger in organizations by Geddes and Callister, (2007) provides an explanation on the valence of anger expression outcomes. The model suggests that organizational norms establish emotion thresholds that may be crossed when employees feel anger. The first "expression threshold" is crossed when an organizational member conveys felt anger to individuals at work who are associated with or able to address the anger-provoking situation. The second "impropriety threshold" is crossed if or when organizational members go too far while expressing anger such that observers and other company personnel find their actions socially and/or culturally inappropriate.

The higher probability of negative outcomes from workplace anger likely will occur in either of two situations. The first is when organizational members suppress rather than express their anger—that is, they fail to cross the "expression threshold". In this instance personnel who might be able to address or resolve the anger-provoking condition or event remain unaware of the problem, allowing it to continue, along with the affected individual's anger. The second is when organizational members cross both thresholds—"double cross"— displaying anger that is perceived as deviant. In such cases the angry person is seen as the problem—increasing chances of organizational sanctions against him or her while diverting attention away from the initial anger-provoking incident. In contrast, a higher probability of positive outcomes from workplace anger expression likely will occur when one's expressed anger stays in the space between the expression and impropriety thresholds. Here, one expresses anger in a way fellow organizational members find acceptable, prompting exchanges and discussions that may help resolve concerns to the satisfaction of all parties involved. This space between the thresholds varies among different organizations and also can be changed in organization itself: when the change is directed to support anger displays; the space between the thresholds will be expanded and when the change is directed to suppressing such displays; the space will be reduced.[44]

Neurology

In neuroimaging studies of anger, the most consistently activated region of the brain was the lateral orbitofrontal cortex.[45] This region is associated with approach motivation and positive affective processes.[46]

Physiology

The external expression of anger can be found in facial expressions, body language, physiological responses, and at times in public acts of aggression.[6] The facial expression and body language are as follows:[8] The facial and skeletal musculature are strongly affected by anger. The face becomes flushed, and the brow muscles move inward and downward, fixing a hard stare on the target. The nostrils flare, and the jaw tends toward clenching. This is an innate pattern of facial expression that can be observed in toddlers. Tension in the skeletal musculature, including raising of the arms and adopting a squared-off stance, are preparatory actions for attack and defense. The muscle tension provides a sense of strength and self-assurance. An impulse to strike out accompanies this subjective feeling of potency.

Physiological responses to anger include an increase in the heart rate, preparing the person to move, and increase of the blood flow to the hands, preparing them to strike. Perspiration increases (particularly when the anger is intense).[47] A common metaphor for the physiological aspect of anger is that of a hot fluid in a container.[8] According to Novaco, "Autonomic arousal is primarily engaged through adrenomedullary and adrenocortical hormonal activity. The secretion by the adrenal medulla of the catecholamines, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, and by the adrenal cortex of glucocorticoids provides a sympathetic system effect that mobilizes the body for immediate action (e.g. the release of glucose, stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen). In anger, the catecholamine activation is more strongly norepinephrine than epinephrine (the reverse being the case for fear). The adrenocortical effects, which have longer duration than the adrenomedullary ones, are modiated by secretions of the pituitary gland, which also influences testosterone levels. The pituitary-adrenocortical and pituitary-gonadal systems are thought to affect readiness or potentiation for anger responding.[8]

Neuroscience has shown that emotions are generated by multiple structures in the brain. The rapid, minimal, and evaluative processing of the emotional significance of the sensory data is done when the data passes through the amygdala in its travel from the sensory organs along certain neural pathways towards the limbic forebrain. Emotion caused by discrimination of stimulus features, thoughts, or memories however occurs when its information is relayed from the thalamus to the neocortex.[22] Based on some statistical analysis, some scholars have suggested that the tendency for anger may be genetic. Distinguishing between genetic and environmental factors however requires further research and actual measurement of specific genes and environments.[48][49]

Philosophical perspectives

Antiquity

Ancient Greek philosophers, describing and commenting on the uncontrolled anger, particularly toward slaves, in their society generally showed a hostile attitude towards anger. Galen and Seneca regarded anger as a kind of madness. They all rejected the spontaneous, uncontrolled fits of anger and agreed on both the possibility and value of controlling anger. There were however disagreements regarding the value of anger. For Seneca, anger was "worthless even for war." Seneca believed that the disciplined Roman army was regularly able to beat the Germans, who were known for their fury. He argued that "...in sporting contests, it is a mistake to become angry".[10]

Aristotle on the other hand, ascribed some value to anger that has arisen from perceived injustice because it is useful for preventing injustice.[10][50] Furthermore, the opposite of anger is a kind of insensibility, Aristotle stated.[10] The difference in people's temperaments was generally viewed as a result of the different mix of qualities or humors people contained. Seneca held that "red-haired and red-faced people are hot-tempered because of excessive hot and dry humors."[10] Ancient philosophers rarely refer to women's anger at all, according to Simon Kemp and K. T. Strongman perhaps because their works were not intended for women. Some of them that discuss it, such as Seneca, considered women to be more prone to anger than men.[10]

Control methods

Seneca addresses the question of mastering anger in three parts: 1. how to avoid becoming angry in the first place 2. how to cease being angry and 3. how to deal with anger in others.[10] Seneca suggests, in order to avoid becoming angry in the first place, that the many faults of anger should be repeatedly remembered. One should avoid being too busy or deal with anger-provoking people. Unnecessary hunger or thirst should be avoided and soothing music be listened to.[10] To cease being angry, Seneca suggests "one to check speech and impulses and be aware of particular sources of personal irritation. In dealing with other people, one should not be too inquisitive: It is not always soothing to hear and see everything. When someone appears to slight you, you should be at first reluctant to believe this, and should wait to hear the full story. You should also put yourself in the place of the other person, trying to understand his motives and any extenuating factors, such as age or illness."[10] Seneca further advises daily self-inquisition about one's bad habit.[10] To deal with anger in others, Seneca suggests that the best reaction is to simply keep calm. A certain kind of deception, Seneca says, is necessary in dealing with angry people.[10]

Galen repeats Seneca's points but adds a new one: finding a guide and teacher can help the person in controlling their passions. Galen also gives some hints for finding a good teacher.[10] Both Seneca and Galen (and later philosophers) agree that the process of controlling anger should start in childhood on grounds of malleability. Seneca warns that this education should not blunt the spirit of the children nor should they be humiliated or treated severely. At the same time, they should not be pampered. Children, Seneca says, should learn not to beat their playmates and not to become angry with them. Seneca also advises that children's requests should not be granted when they are angry.[10]

Medieval era

During the period of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, philosophers elaborated on the existing conception of anger, many of whom did not make major contributions to the concept. For example, many medieval philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Roger Bacon and Thomas Aquinas agreed with ancient philosophers that animals cannot become angry.[10] On the other hand, al-Ghazali (also known as "Algazel" in Europe), who often disagreed with Aristotle and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) on many issues, argued that animals do possess anger as one of the three "powers" in their Qalb ("heart"), the other two being appetite and impulse. He also argued that animal will is "conditioned by anger and appetite" in contrast to human will which is "conditioned by the intellect."[51] A common medieval belief was that those prone to anger had an excess of yellow bile or choler (hence the word "choleric").[10] This belief was related to Seneca's belief that "red-haired and red-faced people are hot-tempered because of excessive hot and dry humors."

Control methods

Maimonides considered being given to uncontrollable passions as a kind of illness. Like Galen, Maimonides suggested seeking out a philosopher for curing this illness just as one seeks out a physician for curing bodily illnesses. Roger Bacon elaborates Seneca's advices. Many medieval writers discuss at length the evils of anger and the virtues of temperance. John Mirk asks men to "consider how angels flee before them and fiends run toward him to burn him with hellfire."[10] In The Canon of Medicine, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) modified the theory of temperaments and argued that anger heralded the transition of melancholia to mania, and explained that humidity inside the head can contribute to such mood disorders.[52]

On the other hand, Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi classified anger (along with aggression) as a type of neurosis,[53] while al-Ghazali (Algazel) argued that anger takes form in rage, indignation and revenge, and that "the powers of the soul become balanced if it keeps anger under control."[54]

Modern times

The modern understanding of anger may not be greatly advanced over that of Aristotle.[10] Immanuel Kant rejects vengeance as vicious because it goes beyond defense of one's dignity and at the same time rejects insensitivity to social injustice as a sign of lacking "manhood." Regarding the latter, David Hume argues that because "anger and hatred are passions inherent in our very frame and constitution, the lack of them is sometimes evidence of weakness and imbecility."[13] Two main differences between the modern understanding and ancient understanding of anger can be detected, Kemp and Strongman state: one is that early philosophers were not concerned with possible harmful effects of the suppression of anger; the other is that, recently, studies of anger take the issue of gender differences into account. The latter does not seem to have been of much concern to earlier philosophers.[10]

The American psychologist Albert Ellis has suggested that anger, rage, and fury partly have roots in the philosophical meanings and assumptions through which human beings interpret transgression.[55] According to Ellis, these emotions are often associated and related to the leaning humans have to absolutistically depreciating and damning other peoples' humanity when their personal rules and domain are transgressed.

Religious perspectives

Catholicism

Anger in Catholicism is counted as one of the seven deadly sins. While Medieval Christianity vigorously denounced anger as one of the seven cardinal, or deadly sins, some Christian writers at times regarded the anger caused by injustice as having some value.[9][10] Saint Basil viewed anger as a "reprehensible temporary madness."[9] Joseph F. Delany in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1914) defines anger as "the desire of vengeance" and states that a reasonable vengeance and passion is ethical and praiseworthy. Vengeance is sinful when it exceeds its limits in which case it becomes opposed to justice and charity. For example, "vengeance upon one who has not deserved it, or to a greater extent than it has been deserved, or in conflict with the dispositions of law, or from an improper motive" are all sinful. An unduly vehement vengeance is considered a venial sin unless it seriously goes counter to the love of God or of one's neighbor.[56]

Hinduism

In Hinduism, anger is equated with sorrow as a form of unrequited desire. The objects of anger are perceived as a hindrance to the gratification of the desires of the angry person.[57] Alternatively if one thinks one is superior, the result is grief. Anger is considered to be packed with more evil power than desire.[58] In the Bhagavad Gita Krishna regards greed, anger, and lust as signs of ignorance and leads to perpetual bondage. As for the agitations of the bickering mind, they are divided into two divisions. The first is called avirodha-prīti, or unrestricted attachment, and the other is called virodha-yukta-krodha, anger arising from frustration. Adherence to the philosophy of the Māyāvādīs, belief in the fruitive results of the karma-vādīs, and belief in plans based on materialistic desires are called avirodha-prīti. Jñānīs, karmīs and materialistic planmakers generally attract the attention of conditioned souls, but when the materialists cannot fulfill their plans and when their devices are frustrated, they become angry. Frustration of material desires produces anger." (The Nectar of Instruction 1)

Buddhism

Anger in Buddhism is defined here as: "being unable to bear the object, or the intention to cause harm to the object." Anger is seen as aversion with a stronger exaggeration, and is listed as one of the five hindrances. Buddhist monks, such as Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetans in exile, sometimes get angry.[59] However, there is a difference; most often a spiritual person is aware of the emotion and the way it can be handled. Thus, in response to the question: "Is any anger acceptable in Buddhism?' the Dalai Lama answered:

"Buddhism in general teaches that anger is a destructive emotion and although anger might have some positive effects in terms of survival or moral outrage, I do not accept that anger of any kind as a virtuous emotion nor aggression as constructive behavior. The Gautama Buddha has taught that there are three basic kleshas at the root of samsara (bondage, illusion) and the vicious cycle of rebirth. These are greed, hatred, and delusion--also translatable as attachment, anger, and ignorance. They bring us confusion and misery rather than peace, happiness, and fulfillment. It is in our own self-interest to purify and transform them."[59]

Buddhist scholar and author Geshe Kelsang Gyatso has also explained Buddha's teaching on the spiritual imperative to identify anger and overcome it by transforming difficulties:

When things go wrong in our life and we encounter difficult situations, we tend to regard the situation itself as our problem, but in reality whatever problems we experience come from the side of the mind. If we responded to difficult situations with a positive or peaceful mind they would not be problems for us. Eventually, we might even regard them as challenges or opportunities for growth and development. Problems arise only if we respond to difficulties with a negative state of mind. Therefore if we want to be free from problems, we must transform our mind.[60]

The Buddha himself on anger:

An angry person is ugly & sleeps poorly. Gaining a profit, he turns it into a loss, having done damage with word & deed. A person overwhelmed with anger destroys his wealth. Maddened with anger, he destroys his status. Relatives, friends, & colleagues avoid him. Anger brings loss. Anger inflames the mind. He doesn't realize that his danger is born from within. An angry person doesn't know his own benefit. An angry person doesn't see the Dharma. A man conquered by anger is in a mass of darkness. He takes pleasure in bad deeds as if they were good, but later, when his anger is gone, he suffers as if burned with fire. He is spoiled, blotted out, like fire enveloped in smoke. When anger spreads, when a man becomes angry, he has no shame, no fear of evil, is not respectful in speech. For a person overcome with anger, nothing gives light.[61]

Islam

The Qur'an, the central religious text of Islam, attributes anger to prophets and believers and Muhammad's enemies. It mentions the anger of Musa (also known as Moses) against his people for worshiping a golden calf; the anger of Yunus (also known as Jonah) Allah in a moment and his eventual realization of his error and his repentance; Allah's removal of anger from the hearts of believers and making them merciful after the fighting against Muhammad's enemies is over.[62][63] In general suppression of anger is deemed a praiseworthy quality and Muhammad is attributed to have said, "power resides not in being able to strike another, but in being able to keep the self under control when anger arises."[63][64][65] Furthermore in another narration the Prophet Muhammad was asked about a short good deed, to which he replied not to be angry then he was asked again and replied with the same answer and when he was asked a third time he said "don't be angry and heaven your reward". Ibn Abdil Barr the Andalusian Maliki jurist explains that controlling anger is the door way for restraining other blameworthy traits. If anger is contained, then it will be easier on the person to subdue other negative aspects like ego and envy, since these two are less powerful than anger. Another proximate saying of Prophet Muhammad instructs that a judge should not pass a judgement between any two parties when he is in a state of anger.

Judaism

In Judaism, anger is a negative trait. In the Book of Genesis, Jacob condemned the anger that had arisen in his sons Simon and Levi: "Cursed be their anger, for it was fierce; and their wrath, for it was cruel."[66]

Restraining oneself from anger is seen as noble and desirable, as Ethics of the Fathers states:

"Ben Zoma said: Who is strong? He who subdues his evil inclination, as it is stated, "He who is slow to anger is better than a strong man, and he who masters his passions is better than one who conquers a city" (Proverbs 16:32). " [67]

Maimonides rules that one who becomes angry is as though that person had worshipped idols.[68] Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi explains that the parallel between anger and idol worship is that by becoming angry, one shows a disregard of Divine Providence - whatever had caused the anger was ultimately ordained from Above - and that through coming to anger one thereby denies the hand of G-d in one's life.[69]

In its section dealing with ethical traits a person should adopt, the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch states:

- "Anger is also a very evil trait and it should be avoided at all costs. You should train yourself not to become angry even if you have a good reason to be angry." [70]

Of God or gods

In many religions, anger is frequently attributed to God or gods. Primitive people held that gods were subject to anger and revenge in anthropomorphic fashion.[71] The Hebrew Bible says that opposition to God's Will results in God's anger.[71] Reform rabbi Kaufmann Kohler explains:

God is not an intellectual abstraction, nor is He conceived as a being indifferent to the doings of man; and His pure and lofty nature resents most energetically anything wrong and impure in the moral world: "O Lord, my God, mine Holy One... Thou art of eyes too pure to behold evil, and canst not look on iniquity."[66]

Christians believe in God's anger in the sight of evil. This anger is not inconsistent with God's love, as demonstrated in the Gospel where the righteous indignation of Christ is shown when he drives the moneychangers from the temple. Christians believe that those who reject His revealed Word, Jesus, condemn themselves, and are not condemned by the wrath of God.[71]

In Islam, God's mercy outweighs his wrath or takes precedence of it.[72] The characteristics of those upon whom God's wrath will fall is as follows: Those who reject God; deny his signs; doubt the resurrection and the reality of the day of judgment; call Muhammad a sorcerer, a madman or a poet; do mischief, are impudent, do not look after the poor (notably the orphans); live in luxury or heap up fortunes; persecute the believers or prevent them from praying.

References

- ^ Videbeck, Sheila L. (2006.). Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Anger definition". Medicine.net. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Harris, W., Schoenfeld, C. D., Gwynne, P. W., Weissler, A. M.,Circulatory and humoral responses to fear and anger, The Physiologist, 1964, 7, 155.

- ^ Raymond DiGiuseppe, Raymond Chip Tafrate, Understanding Anger Disorders, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp.133-159.

- ^ Anger,The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000, Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ a b Michael Kent, Anger, The Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science & Medicine, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-262845-3

- ^ a b Primate Ethology, 1967, Desmond Morris (Ed.). Weidenfeld & Nicolson Publishers: London, p.55

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Raymond W. Novaco, Anger, Encyclopedia of Psychology, Oxford University Press, 2000

- ^ a b c d John W. Fiero, Anger, Ethics, Revised Edition, Vol 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Simon Kemp, K.T. Strongman, Anger theory and management: A historical analysis, The American Journal of Psychology, Vol. 108, No. 3. (Autumn, 1995), pp. 397-417

- ^ a b Sutton, R. I. Maintaining norms about expressed emotions: The case of bill collectors, Administrative Science Quarterly, 1991, 36:245-268

- ^ a b Hochschild, AR, The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling, University of California Press, 1983

- ^ a b Paul M. Hughes, Anger, Encyclopedia of Ethics, Vol I, Second Edition, Rutledge Press

- ^ a b Parker Hall, 2008, Anger, Rage and Relationship: An Empathic Approach to Anger Management, Routledge

- ^ Parker Hall, 2008, Anger, Rage and Relationship: An Empathic Approach to Anger Management, Routledge, London

- ^ Schore AN, 1994, Affect Regulation and the Origin of Self, Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum Associates, Inc

- ^ Harvey D, 2004, personal communication

- ^ Rogers, CR, 1951, Client-Centered Therapy, London, Constable

- ^ angermgmt.com

- ^ Fernandez, E. (2008). "The angry personality: A representation on six dimensions of anger expression." In G. J Boyle, D. Matthews & D. Saklofske (eds.). International Handbook of Personality Theory and Testing: Vol. 2: Personality Measurement and Assessment (pp. 402–419). London: Sage

- ^ International Handbook of Anger. pg 290

- ^ a b "emotion." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, p.11

- ^ Jennifer S. Lerner and Dacher Keltner (2001). "Fear, Anger, and Risk" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81 (1): 146–159. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.146. PMID 11474720.

- ^

Baruch Fischhoff, Roxana M. Gonzalez, Jennifer S. Lerner, Deborah A. Small (2005). "Evolving Judgments of Terror Risks: Foresight, Hindsight, and Emotion" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 11 (2): 134–139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

David DeSteno, Nilanjana Dasgupta, Monica Y. Bartlett, and Aida Cajdric (2004). "Prejudice From Thin Air: The Effect of Emotion on Automatic Intergroup Attitudes" (PDF). Psychological Science. 15 (5): 319–324. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00676.x. PMID 15102141.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Diane M. Mackie, Thierry Devos, Eliot R. Smith (2000). "Intergroup Emotions: Explaining Offensive Action Tendencies in an Intergroup Context" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 79 (4): 602–616. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.602. PMID 11045741.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ International Handbook of Anger. Chapter 17

- ^

D. DeSteno, R. E. Petty, D. T. Wegener, & D.D. Rucker (2000). "Beyond valence in the perception of likelihood: The role of emotion specificity". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 78 (3): 397–416. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.3.397. PMID 10743870.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

DeSteno, D., Petty, R. E., Rucker, D. D., Wegener, D. T., & Braverman, J. (2004). "Discrete emotions and persuasion: The role of emotion-induced expectancies". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 86 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.43. PMID 14717627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/11/101101151730.htm

- ^ a b Tiedens LZ, Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: the effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral, Link: [1], Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 2001 Jan; 80(1):86-94.

- ^ a b Tiedens, Ellsworth & Mesquita, Sentimental Stereotypes: Emotional Expectations for High-and Low-Status Group Members, 2000

- ^ M Sinaceur, LZ Tiedens, Get mad and get more than even: When and why anger expression is effective in negotiations, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2006

- ^ Van Kleef, De Dreu and Manstead, The Interpersonal Effects of Anger and Happiness in Negotiations, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2004, Vol. 86, No. 1, 57–76

- ^ Leland R. Beaumont, Emotional Competency, Anger, An Urgent Plea for Justice and Action, Entry describing paths of anger

- ^ Novaco, R. (1975). Anger control: The development and evaluation of an experimental treatment. Lexington, MA: Heath.

- ^ Beck, Richard (1998). "Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Anger: A Meta-Analysis" (pdf). Cognitive Therapy and Research. 22 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1023/A:1018763902991. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Toward an Integrative Psychotherapy for Maladaptive Anger," International Handbook of Anger.

- ^ "Anger." Gale Encyclopedia of Psychology, 2nd ed. Gale Group, 2001.

- ^ Evidence against catharsis theory:

- Burkeman (2006) Anger Management.

- Green et al. (1975). The facilitation of aggression by aggression: Evidence against the catharsis hypothesis. Abstract. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- ^ Jehn, K. A. 1995. A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40: 256–282.

- ^ Glomb, T. M. 2002. Workplace anger and aggression: Informing conceptual models with data from specific encounters. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7: 20–36.

- ^ Tiedens, L. Z. 2000. Powerful emotions: The vicious cycle of social status positions and emotions. In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. E. J. Ha¨ rtel, & W. J. Zerbe (Eds.), Emotions in the workplace: Research, theory and practice: 71–81. Westport, CT: Quorum.

- ^ Geddes, D. & Callister, R. 2007 Crossing The Line(s): A Dual Threshold Model of Anger in Organizations, Academy of Management Review. 32 (3): 721–746.

- ^ International Handbook of Anger. Chapt 4: Constructing a Neurology of Anger. Michael Potegal and Gerhard Stemmler. 2010

- ^ International Handbook of Anger. Chapt 17. Michael Potegal and Gerhard Stemmler. 2010

- ^ Paul Ekman, Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication, Holt Paperbacks, ISBN 0-8050-7516-X, 2004, p.63

- ^ Xiaoling Wang, Ranak Trivedi, Frank Treiber, and Harold Snieder, Genetic and Environmental Influences on Anger Expression, John Henryism, and Stressful Life Events: The Georgia Cardiovascular Twin Study, Psychosomatic Medicine 67:16–23 (2005)

- ^ Barry Starr, The Tech Museum of Innovation

- ^ According to Aristotle: "The person who is angry at the right things and toward the right people, and also in the right way, at the right time and for the right length of time is morally praiseworthy." cf. Paul M. Hughes, Anger, Encyclopedia of Ethics, Vol I, Second Edition, Rutledge Press

- ^ Haque, Amber (2004). "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377 [367]. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z.

- ^ Haque, Amber (2004). "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377 [366]. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z.

- ^ Haque, Amber (2004). "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377 [362]. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z.

- ^ Haque, Amber (2004). "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377 [366–8]. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z.

- ^ Ellis, Albert (2001). Overcoming Destructive Beliefs, Feelings, and Behaviors: New Directions for Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy. Promotheus Books.

- ^

"Anger" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

"Anger" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Anger, (HinduDharma: Dharmas Common To All), Shri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham

- ^ Anger Management: How to Tame our Deadliest Emotion, by Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami

- ^ a b The Urban Dharma Newsletter, March 9, 2004

- ^ How to Solve our Human Problems, Tharpa Publications (2005, US ed., 2007) ISBN 978-0-9789067-1-9

- ^ "Kodhana Sutta: An Angry Person"(AN 7.60), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight, June 8, 2010

- ^ Examples include: Prophet Musa's anger: Quran 7:150, 154; 20:86; Prophet Yunus's anger: Quran 21:87-8; and Believer's anger: Qur'an 9:15

- ^ a b Bashir, Shahzad. Anger, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, Brill, 2007.

- ^ see for example Quran 3:134; 42:37; Sahih al-Bukhari, vol. 8, bk. 73, no. 135.

- ^ Mohammed Abu-Nimer, Non-Violence, Peacebuilding, Conflict Resolution and Human Rights in Islam:A Framework for Nonviolence and Peacebuilding in Islam, Journal of Law and Religion, Vol. 15, No. 1/2. (2000 - 2001), pp. 217-265.

- ^ a b Kaufmann Kohler, Anger, Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Ethics of the Fathers 4:1

- ^ Rambam, Hilchot de'ot 2

- ^ Sefer HaTanya, p. 535

- ^ Kitzur Shulchan Aruch 29:4

- ^ a b c Shailer Mathews, Gerald Birney Smith, A Dictionary of Religion and Ethics, Kessinger Publishing, p.17

- ^ Gardet, L. Allāh., Encyclopaedia of Islam, Brill, 2007.

Further reading - academic articles

- Managing emotions in the workplace

- Controlling Anger -- Before It Controls You

- The Interpersonal Effects of Anger and Happiness in Negotiations

- Get mad and get more than even: When and why anger expression is effective in negotiations

- Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: the effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral