Blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used in minstrel shows, and later vaudeville, in which performers create a stereotyped caricature of a black person. The practice gained popularity during the 19th century and contributed to the proliferation of stereotypes such as the "happy-go-lucky darky on the plantation" or the "dandified coon".[1] In 1848, blackface minstrel shows were the national art of the time, translating formal art such as opera into popular terms for a general audience.[2] Early in the 20th century, blackface branched off from the minstrel show and became a form in its own right, until it ended in the United States with the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.[3] The Netherlands still holds its annual Christmas alike parade of Sinterklaas featuring Zwarte Piet in full blackface outfit.

Blackface was an important performance tradition in the American theater for roughly 100 years beginning around 1830. It quickly became popular overseas, particularly so in Britain, where the tradition lasted longer than in the US, occurring on primetime TV as late as 1978 (The Black and White Minstrel Show)[4] and 1981.[5] In both the United States and Britain, blackface was most commonly used in the minstrel performance tradition, but it predates that tradition, and it survived long past the heyday of the minstrel show. White blackface performers in the past used burnt cork and later greasepaint or shoe polish to blacken their skin and exaggerate their lips, often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to complete the transformation. Later, black artists also performed in blackface.

Stereotypes embodied in the stock characters of blackface minstrels not only played a significant role in cementing and proliferating racist images, attitudes and perceptions worldwide, but also in popularizing black culture.[6] In some quarters, the caricatures that were the legacy of blackface persist to the present day and are a cause of ongoing controversy. One view is that blackface is a form of cross-dressing.[7]

By the mid-20th century, changing attitudes about race and racism effectively ended the prominence of blackface makeup used in performance in the U.S. and elsewhere. It remains in relatively limited use as a theatrical device, mostly outside the U.S., and is more commonly used today as social commentary or satire. Perhaps the most enduring effect of blackface is the precedent it established in the introduction of African American culture to an international audience, albeit through a distorted lens.[8][9] Blackface's groundbreaking appropriation,[8][9][10] exploitation, and assimilation[8] of African-American culture—as well as the inter-ethnic artistic collaborations that stemmed from it—were but a prologue to the lucrative packaging, marketing, and dissemination of African-American cultural expression and its myriad derivative forms in today's world popular culture.[9][11][12]

History

"Displaying Blackness" and the shaping of racist archetypes

There is no consensus about a single moment that constitutes the origin of blackface. John Strausbaugh places it as part of a tradition of "displaying Blackness for the enjoyment and edification of white viewers" that dates back at least to 1441, when captive West Africans were displayed in Portugal.[13] Whites routinely portrayed the black characters in the Elizabethan and Jacobean theater (see English Renaissance theatre), most famously in Othello (1604).[4] However, Othello and other plays of this era did not involve the emulation and caricature of "such supposed innate qualities of Blackness as inherent musicality, natural athleticism," etc. that Strausbaugh sees as crucial to blackface.[13] Lewis Hallam, Jr., a white actor using blackface makeup of American Company fame, brought blackface in this more specific sense to prominence as a theatrical device in the United States when playing the role of "Mungo", an inebriated black man in The Padlock, a British play that premiered in New York City at the John Street Theatre on May 29, 1769.[14] The play attracted notice, and other performers adopted the style. From at least the 1810s, blackface clowns were popular in the United States.[15] British actor Charles Mathews toured the U.S. in 1822–1823, and as a result added a "black" characterization to his repertoire of British regional types for his next show, A Trip to America, which included Mathews singing "Possum up a Gum Tree", a popular slave freedom song.[16] Edwin Forrest played a plantation black in 1823,[16] and George Washington Dixon was already building his stage career around blackface in 1828,[17] but it was another white comic actor, Thomas D. Rice, who truly popularized blackface. Rice introduced the song "Jump Jim Crow" accompanied by a dance in his stage act in 1828[18] and scored stardom with it by 1832.[19]

First on de heel tap, den on the toe

Every time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow.

I wheel about and turn about an do just so,

And every time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow.[20]

Rice traveled the U.S., performing under the stage name "Daddy Jim Crow". The name Jim Crow later became attached to statutes that codified the reinstitution of segregation and discrimination after Reconstruction.[21]

In the 1830s and early 1840s, blackface performances mixed skits with comic songs and vigorous dances. Initially, Rice and his peers performed only in relatively disreputable venues, but as blackface gained popularity they gained opportunities to perform as entr'actes in theatrical venues of a higher class. Stereotyped blackface characters developed: buffoonish, lazy, superstitious, cowardly, and lascivious characters, who stole, lied pathologically, and mangled the English language. Early blackface minstrels were all male, so cross-dressing white men also played black women who were often portrayed either as unappealingly and grotesquely mannish; in the matronly, mammy mold; or highly sexually provocative. The 1830s American stage, where blackface first rose to prominence featured similarly comic stereotypes of the clever Yankee and the larger-than-life Frontiersman;[22] the late 19th- and early 20th-century American and British stage where it last prospered[23] featured many other, mostly ethnically-based, comic stereotypes: conniving, venal Jews;[24][25] drunken brawling Irishmen with blarney at the ready;[25][26][27] oily Italians;[25] stodgy Germans;[25] and gullible rural rubes.[25]

1830s and early 1840s blackface performers performed solo or as duos, with the occasional trio; the traveling troupes that would later characterize blackface minstrelsy arise only with the minstrel show.[28] In New York City in 1843, Dan Emmett and his Virginia Minstrels broke blackface minstrelsy loose from its novelty act and entr'acte status and performed the first full-blown minstrel show: an evening's entertainment composed entirely of blackface performance. (E. P. Christy did more or less the same, apparently independently, earlier the same year in Buffalo, New York.)[29] Their loosely structured show with the musicians sitting in a semicircle, a tambourine player on one end and a bones player on the other, set the precedent for what would soon become the first act of a standard three-act minstrel show.[30] By 1852, the skits that had been part of blackface performance for decades expanded to one-act farces, often used as the show's third act.[31]

The songs of northern composer Stephen Foster figured prominently in blackface minstrel shows of the period. Though written in dialect and certainly politically incorrect by today's standards, his later songs were free of the ridicule and blatantly racist caricatures that typified other songs of the genre. Foster's works treated slaves and the South in general with an often cloying sentimentality that appealed to audiences of the day.[32]

White minstrel shows featured white performers pretending to be blacks, playing their versions of black music and speaking ersatz black dialects. Minstrel shows dominated popular show business in the U.S. from that time through into the 1890s, also enjoying massive popularity in the UK and in other parts of Europe.[33] As the minstrel show went into decline, blackface returned to its novelty act roots and became part of vaudeville.[23] Blackface featured prominently in film at least into the 1930s, and the "aural blackface"[34] of the Amos 'n' Andy radio show lasted into the 1950s.[34] Meanwhile, amateur blackface minstrel shows continued to be common at least into the 1950s.[35]

As a result, the genre played an important role in shaping perceptions of and prejudices about blacks generally and African Americans in particular. Some social commentators have stated that blackface provided an outlet for whites' fear of the unknown and the unfamiliar, and a socially acceptable way of expressing their feelings and fears about race and control. Writes Eric Lott in Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, "The black mask offered a way to play with the collective fears of a degraded and threatening—and male—Other while at the same time maintaining some symbolic control over them."[36]

Film

Through the 1930s, many well-known entertainers of stage and screen also performed in blackface.[37] Whites who performed in blackface in film included Al Jolson,[38] Eddie Cantor,[39] Bing Crosby,[38] Fred Astaire, Mickey Rooney, Shirley Temple and Judy Garland.[39]

In the early years of film, black characters were routinely played by whites in blackface. In the first known film of Uncle Tom's Cabin (1903) all of the major black roles were whites in blackface.[40] Even the 1914 Uncle Tom starring African American actor Sam Lucas in the title role had a white male in blackface as Topsy.[41] D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915) used whites in blackface to represent all of its major black characters,[42] but reaction against the film's racism largely put an end to this practice in dramatic film roles. Thereafter, whites in blackface would appear almost exclusively in broad comedies or "ventriloquizing" blackness [43] in the context of a vaudeville or minstrel performance within a film.[44] This stands in contrast to made-up whites routinely playing Native Americans, Asians, Arabs, and so forth, for several more decades.[45]

Blackface makeup was largely eliminated even from live film comedy in the U.S. after the end of the 1930s, when public sensibilities regarding race began to change and blackface became increasingly associated with racism and bigotry.[39] Still, the tradition did not end all at once. The radio program Amos 'n' Andy (1928–1960) constituted a type of "aural blackface", in that the black characters were portrayed by whites and conformed to stage blackface stereotypes.[46] The conventions of blackface also lived on unmodified at least into the 1950s in animated theatrical cartoons. Strausbaugh estimates that roughly one-third of late 1940s MGM cartoons "included a blackface, coon, or mammy figure."[47] Bugs Bunny appeared in blackface at least as late as Southern Fried Rabbit in 1953.[48]

Black Minstrel Shows

By 1840, negro performers also were performing in blackface makeup. Frederick Douglass generally abhorred blackface and was one of the first people to write against the institution of blackface minstrelsy, condemning it as racist in nature, with inauthentic, northern, white origins.[50] Douglass did, however, maintain that, "It is something to be gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience."[51]

When all-black minstrel shows began to proliferate in the 1860s, they often were billed as "authentic" and "the real thing". These "colored minstrels"[52] always claimed to be recently-freed slaves (doubtlessly many were, but most were not)[53] and were widely seen as authentic. This presumption of authenticity could be a bit of a trap, with white audiences seeing them more like "animals in a zoo"[54] than skilled performers. Despite often smaller budgets and smaller venues, their public appeal sometimes rivalled that of white minstrel troupes. In March 1866, Booker and Clayton's Georgia Minstrels may have been the country's most popular troupe, and were certainly among the most critically acclaimed.[55]

These "colored" troupes—many using the name "Georgia Minstrels"[56]—focused on "plantation" material, rather than the more explicit social commentary (and more nastily racist stereotyping) found in portrayals of northern blacks.[57] In the execution of authentic black music and the percussive, polyrhythmic tradition of pattin' Juba, when the only instruments performers used were their hands and feet, clapping and slapping their bodies and shuffling and stomping their feet, black troupes particularly excelled. One of the most successful black minstrel companies was Sam Hague's Slave Troupe of Georgia Minstrels, managed by Charles Hicks. This company eventually was taken over by Charles Callendar. The Georgia Minstrels toured the United States and abroad and later became Haverly's Colored Minstrels.[55]

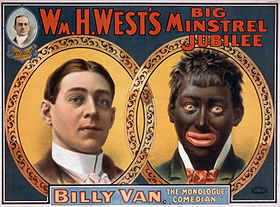

From the mid-1870s, as white blackface minstrelsy became increasingly lavish and moved away from "Negro subjects", black troupes took the opposite tack.[58] The popularity of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and other jubilee singers had demonstrated northern white interest in white religious music as sung by blacks, especially spirituals. Some jubilee troupes pitched themselves as quasi-minstrels and even incorporated minstrel songs; meanwhile, blackface troupes began to adopt first jubilee material and then a broader range of southern black religious material. Within a few years, the word "jubilee", originally used by the Fisk Jubilee Singers to set themselves apart from blackface minstrels and to emphasize the religious character of their music, became little more than a synonym for "plantation" material.[59] Where the jubilee singers tried to "clean up" Southern black religion for white consumption, blackface performers exaggerated its more exotic aspects.[60]

African-American blackface productions also contained buffoonery and comedy, by way of self-parody. In the early days of African-American involvement in theatrical performance, blacks could not perform without blackface makeup, regardless of how dark-skinned they were. The 1860s "colored" troupes violated this convention for a time: the comedy-oriented endmen "corked up", but the other performers "astonished" commentators by the diversity of their hues.[61] Still, their performances were largely in accord with established blackface stereotypes.[62]

These black performers became stars within the broad African-American community, but were largely ignored or condemned by the black bourgeoisie. James Monroe Trotter—a middle class African American who had contempt for their "disgusting caricaturing" but admired their "highly musical culture"—wrote in 1882 that "few… who condemned black minstrels for giving 'aid and comfort to the enemy'" had ever seen them perform.[63] Unlike white audiences, black audiences presumably always recognized blackface performance as caricature, and took pleasure in seeing their own culture observed and reflected, much as they would half a century later in the performances of Moms Mabley.[64]

Despite reinforcing racist stereotypes, blackface minstrelsy was a practical and often relatively lucrative livelihood when compared to the menial labor to which most blacks were relegated. Owing to the discrimination of the day, "corking (or "blacking") up" provided an often singular opportunity for African-American musicians, actors, and dancers to practice their crafts.[65] Some minstrel shows, particularly when performing outside the South, also managed subtly to poke fun at the racist attitudes and double standards of white society or champion the abolitionist cause. It was through blackface performers, white and black, that the richness and exuberance of African-American music, humor, and dance first reached mainstream, white audiences in the U.S. and abroad.[9] It was through blackface minstrelsy that African American performers first entered the mainstream of American show business.[66] Black performers used blackface performance to satirize white behavior. It was also a forum for the sexual double entendre gags that were frowned upon by white moralists. There was often a subtle message behind the outrageous vaudeville routines:

The laughter that cascaded out of the seats was directed parenthetically toward those in America who allowed themselves to imagine that such 'nigger' showtime was in any way respective of the way we live or thought about ourselves in the real world.[67]

With the rise of vaudeville, Antiguan-born actor and comedian Bert Williams became Florenz Ziegfeld's highest-paid star and only African American star.[49][68]

In the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA), an all-black vaudeville circuit organized in 1909, blackface acts were a popular staple. Called "Toby" for short, performers also nicknamed it "Tough on Black Actors" (or, variously, "Artists" or "Asses"), because earnings were so meager. Still, TOBA headliners like Tim Moore and Johnny Hudgins could make a very good living, and even for lesser players, TOBA provided fairly steady, more desirable work than generally was available elsewhere. Blackface served as a springboard for hundreds of artists and entertainers—black and white—many of whom later would go on to find work in other performance traditions. For example, one of the most famous stars of Haverly's European Minstrels was Sam Lucas, who became known as the "Grand Old Man of the Negro Stage".[69] Lucas later played the title role in the 1914 cinematic production of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin.[70] From the early 1930s to the late 1940s, New York City's famous Apollo Theater in Harlem featured skits in which almost all black male performers wore the blackface makeup and huge white painted lips, despite protests that it was degrading from the NAACP. The comics said they felt "naked" without it.[71]

The minstrel show was appropriated by the black performer from the original white shows, but only in its general form. Blacks took over the form and made it their own. The professionalism of performance came from black theater. The black minstrels gave the shows vitality and humor that the white shows never had. As the black social critic LeRoi Jones has written:

It is essential to realize that...the idea of white men imitating, or caricaturing, what they consider certain generic characteristics of the black man's life in American is important if only because of the Negro's reaction to it. (And it is the Negro's reaction to America, first white and then black and white America, that I consider to have made him such a unique member of this society.)[72]

The black minstrel performer was not only poking fun at himself but in a more profound way, he was poking fun at the white man. The cakewalk is caricaturing white customs, while white theater companies attempted to satirize the cakewalk as a black dance. Again, as LeRoi Jones notes:

If the cakewalk is a Negro dance caricaturing certain white customs, what is that dance when, say, a white theater company attempts to satirize it as a Negro dance? I find the idea of white minstrels in blackface satirizing a dance satirizing themselves a remarkable king of irony—which, I suppose is the whole point of minstrel shows.[72]

Authentic or counterfeit

The degree to which blackface performance drew on authentic African American culture and traditions is controversial. Blacks, including slaves, were influenced by white culture, including white musical culture. Certainly this was the case with church music from very early times. Complicating matters further, once the blackface era began, some blackface minstrel songs unquestionably written by New York-based professionals (Stephen Foster, for example) made their way to the plantations in the South and merged into the body of African American folk music.[73]

However, it seems clear that American music by the early 19th century was an interwoven mixture of many influences, and that blacks were quite aware of white musical traditions and incorporated these into their music.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, white-to-black and black-to-white musical influences were widespread, a fact documented in numerous contemporary accounts.[...] [I]t becomes clear that the prevailing musical interaction and influences in the nineteenth century American produced a black populace conversant with the music of both traditions.[74]

Early blackface minstrels often said that their material was largely or entirely authentic to African-American culture; John Strausbaugh, author of Black Like You, said that such claims were likely to be untrue. Well into the 20th century, scholars took the stories at face value.[75] Constance Rourke, one of the founders of what is now known as cultural studies, largely assumed this as late as 1931.[76] In the Civil Rights era there was a strong reaction against this view, to the point of denying that blackface was anything other than a white racist counterfeit.[77] Starting no later than Robert Toll's Blacking Up (1974), a "third wave" has systematically studied the origins of blackface, and has put forward a nuanced picture: that blackface did, indeed, draw on African American culture, but that it transformed, stereotyped, and caricatured that culture, resulting in often racist representations of black characters.[78]

As discussed above, this picture becomes even more complicated after the Civil War, when many African Americans became blackface performers. They drew on much material of undoubted slave origins, but they also drew on a professional performer's instincts, while working within an established genre, and with the same motivation as white performers to make exaggerated claims of the authenticity of their own material.

Author Strausbaugh summed up as follows: "Some minstrel songs started as Negro folk songs, were adapted by White minstrels, became widely popular, and were readopted by Blacks," writes Strausbaugh. "The question of whether minstrelsy was white or black music was moot. It was a mix, a mutt – that is, it was American music."[79]

"Darky" iconography

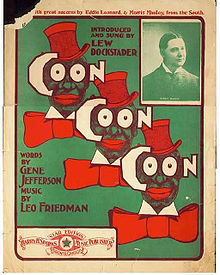

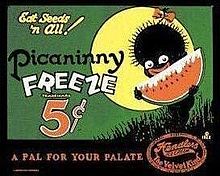

The darky icon itself—googly-eyed, with inky skin; exaggerated white, pink or red lips; and bright, white teeth—became a common motif in entertainment, children's literature, mechanical banks and other toys and games of all sorts, cartoons and comic strips, advertisements, jewelry, textiles, postcards, sheet music, food branding and packaging, and other consumer goods.

In 1895, the Golliwogg surfaced in Great Britain, the product of American-born children's book illustrator Florence Kate Upton, who modeled her rag doll character Golliwogg after a minstrel doll she had in the U.S. as a child. "Golly", as he later affectionately came to be called, had a jet-black face; wild, woolly hair; bright, red lips; and sported formal minstrel attire. The generic British golliwog later made its way back across the Atlantic as dolls, toy tea sets, ladies' perfume, and in myriad other forms. The word golliwog may have given rise to the ethnic slur wog.[80]

U.S. cartoons from the 1930s and 1940s often featured characters in blackface gags as well as other racial and ethnic caricatures. Blackface was one of the influences in the development of characters such as Mickey Mouse.[81] The United Artists 1933 release "Mickey's Mellerdrammer"—the name a corruption of "melodrama" thought to harken back to the earliest minstrel shows—was a film short based on a production of Uncle Tom's Cabin by the Disney characters. Mickey, of course, was already black, but the advertising poster for the film shows Mickey with exaggerated, orange lips; bushy, white sidewhiskers; and his now trademark white gloves.[82]

In the U.S., by the 1950s, the NAACP had begun calling attention to such portrayals of African Americans and mounted a campaign to put an end to blackface performances and depictions. For decades, darky images had been seen in the branding of everyday products and commodities such as Picaninny Freeze, the Coon Chicken Inn[83] restaurant chain and Darkie toothpaste (renamed Darlie) and Blackman mops in Thailand. With the eventual successes of the modern day Civil Rights Movement, such blatantly racist branding practices ended in the U.S., and blackface became an American taboo.

In Japan, in the early 1960s, a toy called Dakkochan became hugely popular. Dakkochan was a black child with large red lips and a grass skirt. There were boy and girl dolls, with the girls being distinguished by a bow. The black skin of the dolls was said to have been significant and in-line with the rising popularity of jazz. Novelist Tensei Kawano went as far as to state, "We of the younger generation are outcasts from politics and society. In a way we are like Negroes, who have a long record of oppression and misunderstanding, and we feel akin to them." [84]

Modern-day manifestations

Over time, blackface and darky iconography became artistic and stylistic devices associated with art deco and the Jazz Age. By the 1950s and '60s, particularly in Europe, where it was more widely tolerated, blackface became a kind of outré, camp convention in some artistic circles. The Black and White Minstrel Show was a popular British musical variety show that featured blackface performers, and remained on British television until 1978. Many of the songs were from the music hall, country and western and folk traditions.[85] Actors and dancers in blackface appeared in music videos such Grace Jones's "Slave to the Rhythm" (1980, also part of her touring piece A One Man Show)[86] and Taco's "Puttin' on the Ritz" (1984).[87]

When trade and tourism produce a confluence of cultures, bringing differing sensibilities regarding blackface into contact with one another, the results can be jarring. Darky iconography is still popular in Japan today, but when Japanese toymaker Sanrio Corporation exported a darky-icon character doll (the doll, Bibinba, had fat, pink lips and rings in its ears)[88] in the 1990s, the ensuing controversy prompted Sanrio to halt production.[89]

Foreigners visiting the Netherlands in November and December are often shocked at the sight of whites in classic blackface as a character known as Zwarte Piet, whom many Dutch nationals love as a holiday symbol. Travelers to Spain have expressed dismay at seeing "Conguito",[90] a tubby, little brown character with full, red lips, as the trademark for Conguitos, a confection manufactured by the LACASA Group. In Britain, "Golly",[91] a golliwog character, fell out of favor in 2001 after almost a century as the trademark of jam producer James Robertson & Sons; but the debate still continues whether the golliwog should be banished in all forms from further commercial production and display, or preserved as a treasured childhood icon. In France, the chocolate powder Banania[92] still uses a little black boy with large red lips as its emblem.

The influence of blackface on branding and advertising, as well as on perceptions and portrayals of blacks, generally, can be found worldwide.

Mexico

In modern day Mexico there are examples of images (usually caricatures) in blackface (i.e.:Memín Pinguín). Though there is backlash from international communities, Mexican society has not protested to have these images changed to racially sensitive images. On the contrary, in the controversial Memín Pinguín cartoon there has been support publicly and politically [93] (chancellor for Mexico, Luis Ernesto Derbez). Currently in Mexico, only 3–4% of the population are composed of Afro-Mexicans (this percentage includes Asian Mexicans).

Netherlands' and Flanders' Zwarte Piet

In Dutch and Flemish folklore, Zwarte Piet—"Black Pete"—is a helper of Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas). The addition of Zwarte Piet to the Saint Nicholas celebration is thought to have originated from a custom on the Dutch islands in the Waddenzee. Once a year young men would cover their faces in ashes and terrorize the streets. This blackening of the face was thought to make the men look like the devil, whom they expected to have a black face. In the past, Zwarte Piet was more identified with the chastising of bad children than the rewarding of the good, but both characters have softened since the mid-19th century, and today the 5 December feast of Saint Nicholas (in the Netherlands, 6 December in Belgium) is mainly an occasion for giving gifts to children.[94] Zwarte Piet inherited many of the classic darky icons, contemporaneous with the spread of darky iconography.[95] The children put their shoes in front of the fireplace, hoping to find a gift in it the next morning. Zwarte Piet is said to climb down the chimney and place the gifts. Children are told Zwarte Piet is black because of the soot. To this day, holiday revellers in the Netherlands blacken their faces, wear afro wigs and bright red lipstick, and walk the streets throwing candy to passers-by.

Accepted without question in the past within an ethnically homogeneous nation, today there is some controversy regarding Zwarte Piet. Most people continue to enjoy this as a cherished tradition and look forward to his annual appearance, while others, especially overseas visitors, see him as a racist caricature[96] and fear it shapes Dutch children's perceptions of black people.[96][97] As a result of the allegations of racism, some of the Dutch have tried replacing Zwarte Piet's blackface makeup with face paint in alternative colors such as green or purple. This practice, however, was widely ridiculed and has since disappeared.[98]

South Africa

Inspired by blackface minstrels who visited Cape Town, South Africa in 1848, former Javanese and Malaysian slaves took up the minstrel tradition, holding emancipation celebrations which consisted of music, dancing and parades. Such celebrations eventually became consolidated into an annual, year-end event called the "Coon Carnival" but now known as the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival or the Kaapse Klopse.

Today, carnival minstrels are mostly Coloured ("mixed race"), Afrikaans-speaking revelers. Often in a pared-down style of blackface which exaggerates only the lips, they parade down the streets of the city in colorful costumes, in a celebration of Creole culture. Participants also pay homage to the carnival's African-American roots, playing Negro spirituals and jazz featuring traditional Dixieland jazz instruments, including horns, banjos, and tambourines.[99] Former South African president Nelson Mandela endorsed the carnival in 1986, while it still bore the "coon" name.

Some have denounced Blackface as an artefact of apartheid accusing broadcasters of lampooning off of disenfranchised African people who still do not control their images of self. Vodacom South Africa has been accused of using non-African actors in Blackface in its advertising as opposed to simple using African actors as principles. Others, mainly Whites, continue to see it as harmless fun.[100]

United States

20th century examples

In 1936 when the lead in touring company of Orson Welles' Voodoo Macbeth (Maurice Evans) fell ill, Welles stepped temporarily into the part and played the role in blackface.[101]

An example of the fascination in American culture with racial boundaries and the color line is demonstrated in the popular duo Amos 'n' Andy, characters played by two white men who performed the show in blackface. They gradually stripped off the blackface makeup during live 1929 performances while continuing to talk in dialect. This fascination with color boundaries had been well-established since the beginning of the century, as it also had been before the Civil War.[102]

In New Orleans in the early 1900s, a group of African American laborers began a marching club in the annual Mardi Gras parade, dressed as hobos and calling themselves "The Tramps". Wanting a flashier look, they later renamed themselves "Zulus" and copied their costumes from a blackface vaudeville skit performed at a local black jazz club and cabaret.[103] The result is one of the best known and most striking krewes of Mardi Gras, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Dressed in grass skirts, top hats and exaggerated blackface, the Zulus of New Orleans are controversial as well as popular.[104]

The wearing of blackface was once a traditional part of the annual Mummers Parade in Philadelphia. Growing dissent from civil rights groups and the offense of the black community led to a 1964 official city policy ruling out blackface.[105] Also in 1964, bowing to pressure from the interracial group Concern, teenagers in Norfolk, Connecticut, reluctantly agreed to discontinue using blackface in their traditional minstrel show that was a fund-raiser for the March of Dimes.[106]

The musician Taco Ockerse stirred up controversy in 1983 by using dancers in blackface for his hit synthpop version of Puttin' on the Ritz.

Former Illinois congressman and House Republican party minority leader Bob Michel caused a minor stir in 1988, when on the USA Today television program he fondly recalled minstrel shows in which he had participated as a young man and expressed his regret that they had fallen out of fashion.[107][108]

In 1993, white actor Ted Danson ignited a firestorm of controversy when he appeared at a Friars Club roast in blackface, delivering a risqué shtick written by his then love interest, African-American comedian Whoopi Goldberg. Recently, gay white performer Chuck Knipp has used drag, blackface, and broad racial caricature while portraying a character named "Shirley Q. Liquor" in his cabaret act, generally performed for all-white audiences. Knipp's outrageously stereotypical character has drawn criticism and prompted demonstrations from black, gay and transgender activists.[109]

21st century

Blackface and minstrelsy also serve as the theme of Spike Lee's film Bamboozled (2000). It tells of a disgruntled black television executive who reintroduces the old blackface style and is horrified by its success.[110]

In recent years, there have been several inflammatory blackface "incidents" where white college students donned blackface as part of possibly innocent, but insensitive, gags, or as part of an acknowledged climate of racism and intolerance on campus. Such incidents usually escalate around Halloween, with students often acting out racial stereotypes.[111][112][113][114]

In November 2005, controversy erupted when journalist Steve Gilliard posted a photograph on his blog. The image was of African American Michael S. Steele, a politician, then a candidate for U.S. Senate. It had been doctored to include bushy, white eyebrows and big, red lips. The caption read, "I's simple Sambo and I's running for the big house." Gilliard, also African American, defended the image, commenting that the politically conservative Steele has "refused to stand up for his people."[115]

In October 2009, a talent-search skit on Australian TV's Hey Hey It's Saturday reunion show featured an Australian tribute group for Michael Jackson, the "Jackson Jive" in blackface, with the Michael Jackson character in whiteface. American performer Harry Connick, Jr. was one of the guest judges and objected to the act, stating that he believed it was offensive to African-Americans, and gave the troupe a score of zero. The show and the group later apologized to Connick, with the troupe leader of Indian descent stating that the skit was not intended to be offensive or racist.[116]

In 2010 An episode of It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia comically explored if Blackface could ever be done "right" [117]

Commodities bearing iconic "darky" images, from tableware, soap and toy marbles to home accessories and T-shirts, continue to be manufactured and marketed in the U.S. and elsewhere. Some are reproductions of historical artifacts, while others are so-called "fantasy" items, newly designed and manufactured for the marketplace. There is a thriving niche market for such item in the U.S., particularly, as well as for original artifacts of darky iconography. The value of vintage "negrobilia" pieces has risen steadily since the 1970s.[118]

United Kingdom

A sketch in a 2003 episode of "Little Britain" features two characters who appear in blackface. The same characters, again in blackface, return for one 2005 sketch. In the sketches, the racist overtones are subverted with the characters presented as belonging to a race genuinely possessing the appearance of white men in blackface (referred to as "Minstrels") who are persecuted by the public and local government in a similar manner to European government treatment of the Romani people.

The character of Papa Lazarou was an evil character who appeared in two episodes of the TV show "The League of Gentlemen", who was regularly in blackface. He also appeared in blackface in the 2005 movie, "The League of Gentlemen's Apocalypse", however it was revealed at the end of the series, when he dressed up as a Caucasian, that this[clarification needed] was actually his skin colour.

Other contexts

There are blackface performance traditions the origins of which stem not from representation of racial stereotype and are not in the stereotypical blackface mode. In Europe, there are a number of folk dances or folk performances in which the black face appears to represent the night, or the coming of the longer nights associated with winter. Many fall or autumn North European folk black face customs are employed ritualistically to appease the forces of the oncoming winter, utilizing characters with blackened faces, or black masks.[119]

In Bacup, Lancashire, England, the Britannia Coco-nut Dancers wear black faces. Some believe the origin of this dance can be traced back to the influx of Cornish miners to northern England, and the black face relates to the dirty blackened faces associated with mining.

In Cornwall, UK several Mummer's Day celebrations are held, these were sometimes known as "Darkie Day" and involved local residents dancing through the streets in blackface to musical accompaniment. Although the origins of blacking-up for Mummer's Day have no racial connotations – the tradition going back to the days of the Celts – controversially, in the Padstow festival, a song with the words "He's gone where the good niggers go", was formerly included due to the popularity of minstrel songs during the 20th century.[120]

In Japan, Ganguro, (from 顔黒, lit. "black face") was an alternative fashion trend of blonde or orange hair and darkened skin among young Japanese women that peaked in popularity around the year 2000, partly as a reaction against the traditional view of white skin being more beautiful and the consequent popularity of white make-up. (See also: Japanese Blackface, Shirabyōshi, Geisha and Butoh.)

In Nowruz celebrations in Iran, Hajji Firuz performers blacken their faces, and each "wears very colorful clothes, usually — but not always — red, and always a hat that is sometimes long and cone-shaped. His songs, quite traditional in wording and melody, are very short repetitive".[121] Iranian-American scholars Golbarg Bashi and Hamid Dabashi offer an anti-racist critique of the figure of Hajji Firuz and called for the elimination of the figure of Blackface from the Nowruz festivities. In their piece they write of the "deeply racist figure of Blackface Hajji Firuz, doubtless a nasty remnant of African slaves that were bought and sold and made into an object of ridicule at the same time. We have been horrified to see Iranians celebrate the Noruz here in the US in colorful parades down Fifth Avenue, an otherwise perfectly beautiful thing to do, while parading a figure of Hajji Firuz, much to the horror of African-Americans who cannot believe that in this day and age there are still people that flaunt such racist acts unconsciously." [122]

In the 1976 Soviet film How Tsar Peter the Great Married Off His Moor (Сказ про то, как царь Пётр арапа женил), the iconic singer Vladimir Vysotsky performs the role of the Moor in blackface.

In West African folk theatre and puppetry there is a tradition of satirical representation of white Europeans. Performers will wear white masks and white gloves. In the Yoruba Egungun festivals overly affectionate white couples are made fun of due to their unseemly and ridiculous behaviour.[123] The imagery is very similar to the representation of white colonists, sometimes with a humorous undercurrent, in wood carvings from the same regions.[124]

In Thailand, actors darken their faces to portray the Negrito of Thailand in a popular play by King Chulalongkorn (1868–1910), Ngo Pa (Template:Lang-th), which has been turned into a musical and a movie.[125]

Legacy

Despite its racist portrayals, blackface minstrelsy was the conduit through which African-American and African-American-influenced music, comedy, and dance first reached the American mainstream.[9] It played a seminal role in the introduction of African-American culture to world audiences. Wrote jazz historian Gary Giddins in Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years 1903–1940:

Though antebellum (minstrel) troupes were white, the form developed in a form of racial collaboration, illustrating the axiom that defined – and continues to define – American music as it developed over the next century and a half: African-American innovations metamorphose into American popular culture when white performers learn to mimic black ones.

— [126]

In a specific example of this, from Ted Fox's Showtime at the Apollo

Elvis Presley, a young, still raw hayseed, was making his first trip to the Big Apple to see his new record company, and the Apollo was where he wanted to be. Night after night in New York he sat in the Apollo transfixed by the pounding rhythms, the dancing and prancing, the sexual spectacle of rhythm-and-blues masters like Bo Diddley...In 1955, Elvis's stage presence was still rudimentary. But watching Bo Diddley charge up the Apollo crowd undoubtedly had a profound effect on him. When he returned to New York a few months later for his first national television appearance, on Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey's "Stage Show," he again spent hours at the Apollo after rehearsals. On the Dorsey show Elvis shocked the entire country with his outrageous hip-shaking performance, and the furor that followed made him an American sensation.

— [67]

Many of country's earliest stars, such as Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills, were veterans of blackface performance.[127][128][129] More recently, the American country music television show Hee Haw (1969–1993) had the format and much of the content of a minstrel show.[130]

The immense popularity and profitability of blackface were testaments to the power, appeal, and commercial viability of not only black music and dance, but also of black style. This led to cross-cultural collaborations, as Giddings writes; but particularly to the often ruthless exploitation and outright theft of African-American artistic genius, as well—by other, white performers and composers; agents; promoters; publishers; and record company executives.[131][132][133][134][135]

While blackface in the literal sense has played only a minor role in entertainment in recent decades, various writers see it as epitomizing an appropriation and imitation of black culture that continues today. As noted above, Strausbaugh sees blackface as central to a longer tradition of "displaying Blackness".[13] "To this day," he writes, "Whites admire, envy and seek to emulate such supposed innate qualities of Blackness as inherent musicality, natural athleticism, the composure known as 'cool' and superior sexual endowment," a phenomemon he views as part of the history of blackface.[13] For more than a century, when white performers have wanted to appear sexy, (like Elvis[136][137] or Mick Jagger[138]); or streetwise, (like Eminem);[138][139] or hip, (like Mezz Mezzrow);[140] they often have turned to African-American performance styles, stage presence and personas.[141] Pop culture referencing and cultural appropriation of African-American performance and stylistic traditions—often resulting in tremendous profit—is a tradition with origins in blackface minstrelsy.[131]

The international imprint of African-American culture is pronounced in its depth and breadth, in indigenous expressions, as well as in myriad, blatantly mimetic and subtler, more attenuated forms.[142] This "browning", à la Richard Rodriguez, of American and world popular culture began with blackface minstrelsy.[131] It is a continuum of pervasive African-American influence which has many prominent manifestations today, among them the ubiquity of the cool aesthetic[143][144] and hip hop culture.[145]

See also

|

References

- ^ For the "darky"/"coon" distinction see, for example, note 34 on p. 167 of Edward Marx and Laura E. Franey's annotated edition of Yone Noguchi, The American Diary of a Japanese Girl, Temple University Press, 2007, ISBN 1-59213-555-2. See also Lewis A. Erenberg (1984), Steppin' Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890–1930, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-21515-6 , p. 73. For more on the "darky" stereotype, see J. Ronald Green (2000), Straight Lick: The Cinema of Oscar Micheaux, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-33753-4, p. 134, 206; p. 151 of the same work also alludes to the specific "coon" archetype.

- ^ Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture by William J. Mahar, University of Illinois Press (1998) p. 9 ISBN 0-252-06696-0.

- ^ A History of the Minstrel Show By Frank W. Sweet, Backintyme (2000) p. 25, ISBN 0939479214

- ^ a b Strausbaugh 2006, p. 62

- ^ "Roots?". Are You Being Served?. Episode 8. 1981-12-24. BBC1.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|episodelink=(help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|seriesno=ignored (|series-number=suggested) (help) - ^ Lott, Eric. "Blackface and Blackness: The Minstrel Show in American Culture" Inside the minstrel mask: readings in nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy Ed. Annemarie Bean, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara. pp. 5-6

- ^ Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot (1998) by Michael Rogin, University of California Press, p. 30 ISBN 0-520-21380-7

- ^ a b c Lott 1993, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b c d e Watkins 1999, p. 82

- ^ Inside the minstrel mask: Readings in nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy by Bean, Annemarie, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara. 1996. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- ^ Color-Blind Ideology and the Cultural Appropriation of Hip-Hop Jason Rodriquez, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 35, No. 6, 645–668 (2006)

- ^ Darktown Strutters. – book reviews African American Review, Spring, 1997 by Eric Lott

- ^ a b c d Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 35–36

- ^ Tosches, Nick (2002). Where Dead Voices Gather. Back Bay. p. 10. ISBN 0316895377.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 68

- ^ a b Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. p.489

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 74 et. seq.

- ^ Lott 1993, p. 211

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 67

- ^ isbn=0306807432

- ^ Ronald L. F. Davis, Creating Jim Crow, The History of Jim Crow online, New York Life. Accessed 31 January 2008.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 27

- ^ a b Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 130–131

- ^ Jody Rosen (2006), album notes to Jewface, Reboot Stereophonic CD RSR006

- ^ a b c d e Strausbaugh 2006, p. 131

- ^ Michael C. O'Neill, O'Neill's Ireland: Old Sod or Blarney Bog?, Laconics (eOneill.com), 2006. Accessed online 2 February 2008.

- ^ Pat, Paddy and Teague, The Independent (London), January 2, 1996. Accessed online (at findarticles.com) 2 February 2008.

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 30

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 102–103

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 51–52

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 56–57

- ^ Key, Susan. "Sound and Sentimentality: Nostalgia in the Songs of Stephen Foster." American Music, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Summer, 1995), pp. 145–166.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 126

- ^ a b Strausbaugh 2006, p. 225

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 145–149

- ^ Lott 1993, p. 25

- ^ One extensive list can be found at Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 222–225.

- ^ a b Smith, Rj, "Pardon the Expression" (book review), Los Angeles Magazine, August 2001. Accessed online 2 February 2008.

- ^ a b c John Kenrick, Blackface and Old Wounds. Musicals101.com. Accessed online 2 February 2008.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 203–204

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 204–206

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 211–212

- ^ Michael Rogin, Blackface, White Noise:Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot (1998), University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21380-7, p. 79.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 214

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 214–215

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 225; the televised version (1951–1953) used African American actors.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 240

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 241

- ^ a b Strausbaugh 2006, p. 136

- ^ Granville Ganter, "He made us laugh some": Frederick Douglass's humor, originally published in African American Review, December 22, 2003. Online at HighBeam Encyclopedia. Accessed online 2 February 2008.

- ^ Frederick Douglass, Gavitt's Original Ethiopian Serenaders, originally published in The North Star (Rochester), 29 June 1849. Online in Stephen Railton, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Culture, University of Virginia. Accessed online 31 January 2008.

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 199

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 198, 236–237

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 206

- ^ a b Toll 1974, p. 205

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 203

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 179, 198

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 234

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 236–237, 244

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 243

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 200

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 180

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 226–228, including the quotation from Trotter.

- ^ Toll 1974, pp. 258–259

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 195

- ^ Toll 1974, p. 228

- ^ a b Fox, Ted (1983). Showtime at the Apollo. Da Capo. pp. 5, 92–92. ISBN 0-647-01612-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Margo Jefferson, Blackface Master Echoes in Hip-Hop, New York Times, October 13, 2004. Accessed online 2 February 2008.

- ^ Johnson (1968). Black Manhattan, p. 90. Quoted in Toll 1974, p. 218

- ^ Uncle Tom's Cabin (1914), IMDB. Accessed 31 January 2008.

- ^ Fox, Ted (1983). Showtime at the Apollo. Da Capo. p. 4. ISBN 0-647-01612-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ a b

Jones, Leroy (1963). Blues People: The Negro Experience in White America and the Music that Developed from It. Ny: TMorrow Quill Paperbacks. pp. 85–86. ISBN 0-688-18474-x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 70–72

- ^

Floyd, Jr., Samuel A. (1995). The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States. NY: Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-19-590975-9.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 69

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 27–28

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 70

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 70; Toll 1974 passim.

- ^ John, Strausbaugh. "Amazon.com: Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult & Imitation in American Popular Culture: John Strausbaugh,Darius James: Books". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ The Golliwog Caricature, Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University. Accessed online 31 January 2008.

- ^ Sacks and Sacks 158.

- ^ "Mickey's Mellerdrammer." Linen-mounted movie poster. Hake's Americana & Collectibles, sales site. Retrieved 01-14-2008.

- ^ Coon Chicken Inn Photos and history of the restaurant chain.

- ^ "JAPAN: Dakkochan Delirium". Time. 1960-08-29. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Minstrels founder Mitchell dies, BBC, 29 August 2002. Accessed 2 February 2008.

- ^ Miriam Kershaw, Postcolonialism and androgyny: the performance art of Grace Jones[dead link], Art Journal, Winter 1997, p. 5[dead link]. Accessed online 17 July 2008 at FindArticles.com.

- ^ "Taco – Puttin' on the Ritz (Original Uncensored Version)". YouTube. Retrieved 01–12–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Sherick A. Hughes, "The Convenient Scapegoating of Blacks in Postwar Japan: Shaping the Black Experience Abroad", Journal of Black Studies (Sage Publications, Inc.), Vol. 33, No. 3, (January 2003), pp. 335–353; p. 342. Accessed at http://www.jstor.org/stable/3180837 (subscription link), 14 May 2008.

- ^ John Greenwald with reporting by Kumiko Makihara, Japan Prejudice and Black Sambo, Time Magazine, June 24, 2001. Accessed online 20 May 2008.

- ^ "Conguitos". Archived from the original on 2007-01-01.

- ^ "The African-American Image Abroad: Golly, It's Good!".

- ^ [1] Banania's Official Website

- ^ "Hace EU el 'ridículo' al criticar a Memín Pinguín: Derbez (It was ridiculous for the EU to criticize Memín Pinguín) url=http://www.esmas.com/noticierostelevisa/mexico/457430.html".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help); Missing pipe in:|title=(help) - ^ Booij, Frits. "Opzoek naar Zwarte Piet (in search of Zwarte Piet)". Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ "Sinterklaas:Illustraties". 1814–1948. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b "Surviving Zwarte Piet – a Black mother in the Netherlands copes with a racist institution in Dutch culture, Essence". December 1997.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Annual Zwarte Piet debate – Expatica". Expatica.com. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ Template:Nl icon Piet weer zwart ("Pete black again"), De Telegraaf, November 15, 2007. Accessed online February 17, 2008.

- ^ "Coon Carnival Cape Town". Web.archive.org. 2005-10-27. Archived from the original on 2005-10-27. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ "South Africa 2010 Report". African Holocaust Society.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Callow, Simon (1995). Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu. Penguin. p. 145. ISBN 0-670-86722-5.

- ^ Stowe, David W. (1994). Swing Changes: Big-Band Jazz in New Deal America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN 0-674-85825-5.

- ^ "Zulu Blackface: The Real Story!". Archived from the original on 2006-02-27.

- ^ The Zulu Parade of Mardi Gras, American Experience web site, PBS. Accessed 16 July 2008.

- ^ John Francis Marion, Smithsonian Magazine, January 1981. "On New Year's Day in Philadelphia, Mummer's the word". Archived version accessed 4 January 2008.

- ^ Joseph A. O'Brien, The Hartford Courant, January 30, 1964.[2]. Accessed 3 February 2011.

- ^ Chicago Sun-Times Editorial, "Michel remarks insulting," Nov. 16, 1988

- ^ Michel, Bob. "My Sincere Apologies" Chicago Sun-Times November 18, 1988

- ^ Blackface Drag Again Draws Fire Gay City News. Volume 3, Issue 308 | February 19–25, 2004

- ^ Bamboozled (2000), IMDB. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ Johnson, Sophie."‘Blackface' incident ignites campus." Whitman College Pioneer, October 26, 2006. Retrieved on 11-27-2007.

- ^ Walter, Vic."Gates' Unfinished Business: Racism at Texas A&M." ABC News, The Blotter, November 10, 2006. Retrieved on 11-27-2007.

- ^ Editorial. "Blackface a Black Mark for Every Student[dead link] The Daily Illini, October 31, 2007. Retrieved on 12–2–07.

- ^ Connolly, Joe."Blackface Makes Its Way To College Campuses." The Daily Orange, November 11, 2003. Retrieved on 11–26–07.

- ^ James W. Brosnan (2005-10-27). "Virginia governor's candidate pulls ads after 'Sambo' attack". Scripps Howard News Service. Archived from the original on 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Evelyne Yamine, Gareth Trickey and Chris Scott. Hey Hey sees red over black face Jackson 5 act, The Daily Telegraph, October 08, 2009

- ^ Sims, David (2011-07-05). ""Dee Reynolds: Shaping America's Youth" | It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia | TV Club | TV". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ Leah Dilworth (2003), Acts of Possession: : Collecting in America, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-3272-8. p. 255.

- ^ Masks: the Art of Expression edit. John Mack/pub. British Museum 1994 ISBN 0-7141-2507-5/'The Other Within: Masks and masquerades in Europe' Cesayo Dogre Poppi

- ^ now to post a comment!. "Darkie Day". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ Mahmoud Omidsalar, HÂJI FIRUZ – The Herald of Iranian New-Year, in CAIS, The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies

- ^ "Feature | Sal-e No Mobarak!". Tehran Avenue. 2006-03-21. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ Icons; Ideals and Power in the Art of Africa; Herbert M. Cole; National Museum of African Art; Washington DC and London; ISBN 0-87474-320-6; pp25-27

- ^ Art and Religion in Africa; Rosalind I.J. Hackett; Cassell 1996: ISBN 0-304-70424-5 p.193 quoting Babatunde Lawal, 1993, "Oyibo: Representation of the Colonialist Other in Yoruba Art. Discussion Paper, Boston University.

- ^

Keyes, Charles F. (1995). The golden peninsula : culture and adaptation in mainland Southeast Asia. Includes bibliographical references and index. Honolulu: (SHAPS library of Asian studies) University of Hawai'i Press. p. 34. ISBN 082481696x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Gary Giddings, Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years 1903–1940 (2001), Back Bay Books, ISBN 0-316-88645-9. p. 78.

- ^ Nolan Porterfield, Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America's Blue Yodeler (1979), University of Indiana Press, ISBN 0-252-00750-6. p. 261.

- ^ Charles Townsend, San Antonio Rose: The Life and Music of Bob Wills (1986), University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-01362-X, p. 45.

- ^ Nick Tosches, Where Dead Voices Gather (2002), Back Bay, ISBN 0-316-89537-7, p. 66.

- ^ Lott 1993, p. 5

- ^ a b c Toll 1974, p. 51

- ^ Barlow, William. "Black Music on Radio During the Jazz Age," African American Review, Summer 1995.

- ^ Kofsky, Frank (1998). Black Music, White Business: Illuminating the History and Political Economy of Jazz. Pathfinder Press.

- ^ Reich, Howard and Gaines, William."Jelly Roll Blues: The Great Jazz Swindle[dead link]," Part 1 of 3. The Chicago Tribune, November 28, 2007. Retrieved on 11-29-2007.

- ^ "Whites, Blacks and the Blues", "The Blues" Teacher's Guide, PBS. Retrieved on 12-18-2008.

- ^ Kolawole, Helen."He Wasn't My King." The Guardian Unlimited, August 15, 2002. Retrieved on 11-29-2007.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 61: not about "sexiness", but makes an explicit analogy between T.D. Rice with "Jump Jim Crow" and Elvis Presley with "Hound Dog".

- ^ a b Strausbaugh 2006, p. 218 explicitly analogizes Al Jolson's style of blackface to Jagger and Eminem: "not mockery, but the sincere mimicry of a non-Black artist who loves Black culture (or what he thinks is Black culture) so dearly he can't resist imitating it, even to the ridiculous point of blacking up."

- ^ Cunningham, Daniel Mudie. "Larry Clark: Trashing the White American Dream." The Film Journal. Retrieved on 2006-08-25

- ^ Roediger, David (1997). "The First Word in Whiteness: Early Twentieth-Century European Immigration", Critical White Studies: Looking Behind the Mirror. Temple University Press, p. 355.

- ^ Strausbaugh 2006, p. 40: "To this day, Whites admire, envy and seek to emulate such supposed innate qualities of Blackness as inherent musicality, natural athleticism, the composure known at 'cool' and superior sexual endowment." Conversely, up to and including the Civil Rights era, "aspirational" black performers imitated white style: Strausbaugh 2006, p. 140

- ^ Joel Hoard, "Fa shizzle dizzle, it's cultural appropriation-izzle", The Michigan Daily, April 19, 2004. Retrieved on 12-18-2008.

- ^ Southgate, Nick."Coolhunting, account planning and the ancient cool of Aristotle." Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Vol. 21, Issue 7, pp. 453–461, 2003. Citation for the ubiquity. Retrieved on 03-02-2007.

- ^ Robert Farris Thompson, "An Aesthetic of the Cool", African Arts, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973), p. 40-43, 64–67, 89–91. Citation for African (more specifically, Yoruba) origin of "cool".

- ^ MacBroom, Patricia. "Rap Locally, Rhyme Globally: Hip-Hop Culture Becomes a World-Wide Language for Youth Resistance, According to Course." News, Berkeleyan. 2000-05-02. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

Bibliography

- Armstron-De Vreeze, Pamela (1997). "Surviving Zwarte Piet — a Black mother in the Netherlands copes with a racist institution in Dutch culture". Essence magazine. Archived from the original on 2005-05-16. Retrieved 2005-11-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Hughes, Langston and Meltzer, Milton (1967). Black Magic: A Pictorial History of Black Entertainers in America. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-306-80406-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lott, Eric (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195078322.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malik, Sarita. "The Black and White Minstrel Show". Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- Sacks, Howard L, and Sacks, Judith (1993). Way up North in Dixie: A Black Family's Claim to the Confederate Anthem. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Strausbaugh, John (2006). Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult and Imitation in American Popular Culture. Jeremy P. Tarcher / Penguin. ISBN 1585424986.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toll, Robert C. (1974). Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0819563005.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Twain, Mark (1924). "XIX, dictated 1906-11-30". Mark Twain's Autobiography. New York: Albert Bigelow Paine. LCCN 24025122.

- Watkins, Mel (1999). On the Real Side: A History of African American Comedy from Slavery to Chris Rock. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 1-55652-351-3.

- Further reading

- Cockrell, Dale (1997). Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and their World. Cambridge Studies in American Theatre and Drama. ISBN 0-521-56828-5.

- Levinthal, David (1999). Blackface. Arena. ISBN 1-892041-06-5.

- Lhamon, Jr., W.T. (1998). Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-74711-9.

- Rogin, Michael (1998). Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21380-7.

- Abbott, Lynn, & Seroff, Doug (2008). Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, "Coon Songs," and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-901-7.

- Chude-Sokei, Louis (2005). The Last Darky: Bert Williams, Black-on-Black Minstrelsy and the African Diaspora. Duke University Press. ISBN 082233643X.

External links

- General

- "Blackface and other historic racial images from the Authentic History Center"

- "Bambizzoozled – Blackface in Movies and Television"

- "The Blackface Stereotype", Manthia Diawara

- "Cape Minstrel Festival Kaapse Klopse", Cape Town Magazine.

- Recent blackface stories in the news, from the Colorblind Society

- "Zulu Blackface: The Real Story!"

- "The New Era of Blackface," Louis Chude-Sokei

- "The History of Racist Blackface Stereotypes

- "Blacking Up: Hip-Hop's Remix of Race and Identity

- Zwarte Piet