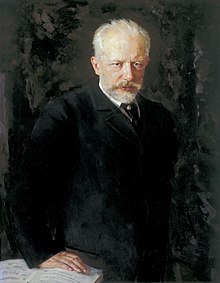

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by ARBN19 (talk | contribs) 12 years ago. (Update timer) |

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈpiːtər ˈɪl[invalid input: 'ɨ']tʃ tʃaɪˈkɒfski/); (Russian: Пётр Ильич Чайковский[a 1]) (May 7, 1840 – November 6, 1893[a 2]) was a Russian composer whose works included symphonies, operas, ballets, and chamber music. Some of these rate amongst the most popular concert and theatrical music in the classical repertoire.

Despite his musical precocity, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant. Against the wishes of his family, he pursued a musical career and entered the Saint Petersburg Conservatory from which he graduated in 1865. This formal Western-oriented training set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five, with whom Tchaikovsky's professional relationship was mixed.

Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky's life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors include leaving his mother for boarding school, his mother's early death, his suppressed homosexuality, and the collapse of the one enduring relationship of his adult life, his 13-year association with the wealthy widow Nadezhda von Meck. His sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera, but some attribute it to suicide.

During his life, Tchaikovsky was honored by the Tsar and awarded a lifetime pension. His music was extremely popular then, and still is today, although critics have sometimes dismissed it as lacking in elevated thought. By the end of the 20th century, however, Tchaikovsky's status as a significant composer had become secure.

Life

Childhood

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, a small town in present-day Udmurtia, a former province of Vyatka in the Russian Empire. His family had a long line of military service. His father, Ilya Petrovich Tchaikovsky, was an engineer of Ukrainian descent who served as a lieutenant colonel in the Department of Mines[1] and manager of the Kamsko-Votkinsk Ironworks.[2] His grandfather, Petro Fedorovych Chaika, received medical training in Saint Petersburg and served as a physician's assistant in the army before becoming city governor of Glazov in Viatka.[2] His great-grandfather, a Cossack named Fyodor Chaika, distinguished himself under Peter the Great at the Battle of Poltava in 1709.[3] His mother, Alexandra Andreyevna née d'Assier, was 18 years her husband's junior and of French ancestry on her father's side, and the second of Ilya's three wives.[2][4] Both of Tchaikovsky's parents were trained in the arts, including music. This was considered a necessity as postings to remote areas of Russia were always possible and with them the need for entertainment, both privately and at social gatherings.[5]

Tchaikovsky had four brothers (Nikolai, Ippolit, and twins Anatoly and Modest), a sister, Alexandra and a half-sister Zinaida from his father's first marriage.[6] He was particularly close to Alexandra and the twins. Anatoly later had a prominent legal career, while Modest became a dramatist, librettist, and translator.[7] Alexandra married Lev Davydov[8] and had seven children, one of whom, Vladimir Davydov, nicknamed 'Bob' by the composer, was to become very close to the composer.[9] The Davydovs provided the only real family life Tchaikovsky knew as an adult,[10] and their estate in Kamianka (now part of Ukraine) became a welcome refuge for him during his years of wandering.[10]

In 1843 the family hired Fanny Dürbach, a 22-year old French governess, to look after the children and teach Tchaikovsky's elder brother Nikolai and a niece of the family.[11] While Tchaikovsky, at four and a half, was initially considered too young to begin studies, his insistence convinced Dürbach otherwise.[12] Dürbach turned out to be an excellent teacher, teaching Pyotr Tchaikovsky to be fluent in French and German by the age of six.[13] Tchaikovsky became attracted to the young woman and her affection for him is said to have provided a counter to Tchaikovsky's mother, who has been described as a cold, unhappy, distant parent [14], although others assert that the mother doted on her son.[15] Dürbach saved much of Tchaikovsky's work from this period, which includes his earliest known compositions.[16] She was also the source of several anecdotes about his childhood.[17]

Tchaikovsky took piano lessons from the age of five. A precocious pupil, he could read music as adeptly as his teacher within three years. His parents were initially supportive, hiring a tutor, buying an orchestrion (a form of barrel organ that could imitate elaborate orchestral effects), and encouraging his study of the piano for both aesthetic and practical reasons.[18] Nevertheless, the family decided in 1850 to send Tchaikovsky to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg. This decision may have been rooted in practicality. It is not certain whether Tchaikovsky's parents had grown insensitive toward his musical gift.[19] However, regardless of talent, unless you were an affluent aristocrat, the only avenues for a musical career in Russia at that time were as a teacher in an academy or an instrumentalist in one of the Imperial Theaters. Both were considered on the lowest rung of the social ladder, with no more rights than peasants.[20] Also, because of the growing uncertainty of his father's income, both parents may have wanted Tchaikovsky to become independent as soon as possible.[21]

Since both parents had graduated from institutes in Saint Petersburg, they decided to educate him as they had themselves been educated.[22] The School of Jurisprudence mainly served the lesser nobility and would prepare Tchaikovsky for a career as a civil servant. As the minimum age for acceptance was 12 and Tchaikovsky was only 10 at the time, he was required to spend two years boarding at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence's preparatory school, 800 miles (1,300 km) from his family.[23] Once those two years had passed, Tchaikovsky transferred to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence to begin a seven-year course of studies.[24]

Emerging composer

Childhood trauma and school years

Tchaikovsky's separation from his mother due to boarding school caused an emotional trauma that tormented him throughout his life.[25][26] Her death from cholera in 1854 further devastated him, affecting him so much that he could not inform Fanny Dürbach until two years later.[27] He mourned his mother's loss for the rest of his life[28] and called it "the crucial event" that would ultimately shape it.[29] More than 25 years after his loss, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, "Every moment of that appalling day is as vivid to me as though it were yesterday."[28] The loss also prompted Tchaikovsky to make his first serious attempt at composition, a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky's father, who also contracted cholera at this time but fully recovered, immediately sent him back to school, hoping that classwork would occupy the boy's mind.[30] To compensate for his isolation and loss, Tchaikovsky made lifelong friendships with fellow students, including Aleksey Apukhtin and Vladimir Gerard.[30][31] Music became a unifier. While it was not an official priority at the School of Jurisprudence,[32] Tchaikovsky maintained a extracurricular connection by regularly attending the opera with other students.[33] Fond of works by Rossini, Bellini, Verdi and Mozart, he would improvise for his friends at the school's harmonium on themes they had sung during choir practice. "We were amused," Vladimir Gerard later remembered, "but not imbued with any expectations of his future glory."[34] The piano manufacturer Franz Becker, on occasional visits as a music teacher, gave Tchaikovsky his only formal instruction in that area.

In 1855, Tchaikovsky's father funded private lessons for his son with the teacher Rudolph Kündinger. He also questioned Kündinger about a musical career for the boy. Kündinger replied that, while impressed with Tchaikovsky's improvisation at the keyboard, nothing to him suggested a potential composer or even a fine performer.[35] Kündinger later admitted that his assessment was also based on his own negative experiences as a musician in Russia and his unwillingness for Tchaikovsky to be treated likewise.[36] Regardless, Tchaikovsky was told to finish his course and then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice.[37] Even though he gave this piece of practical advice, his father remained receptive about a career in music for Tchaikovsky. He merely did not know Tchaikovsky could accomplish or make a living at it. No public education system in music existed at the time in Russia and private education, especially in composition, was highly erratic.[38]

Civil service; pursuing music

On June 10, 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated with the rank of titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed five days later to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He would remain a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.[39]

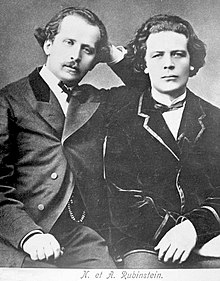

In 1861, Tchaikovsky attended classes in music theory taught by Nikolai Zaremba at the Mikhailovsky Palace (now the Russian Museum) in Saint Petersburg.[40] These classes were organized by the Russian Musical Society (RMS), founded in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (a German-born aunt of Tsar Alexander II) and her protégé, pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein. The aim of the RMS was to foster native talent, in accordance with Alexander II's stated intent.[41] (Previous tsars and the aristocracy had focused almost exclusively on importing European talent.[42]) The RMS fulfilled Alexander II's wish by promoting a regular season of public concerts (previously held only during the six weeks of Lent, when the Imperial Theaters were closed[43]) and providing basic professional training in music.[44] The classes held at the Mikhailovsky Palace were a precursor to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which opened in 1862. Tchaikovsky enrolled at the Conservatory as part of its premiere class but held onto his Ministry post until the following year, wanting to make sure his course lay in music.[45] From 1862 to 1865 he studied harmony and counterpoint with Zaremba. Rubinstein, director and founder of the Conservatory, taught instrumentation and composition.[46]

Tchaikovsky benefited from his Conservatory studies in two ways. First, it transformed him into a musical professional and gave him tools that would help him thrive as a composer. Second, his in-depth exposure to European principles and forms for organizing musical material gave Tchaikovsky the sense that his art belonged to world culture and was not exclusively Russian or Western. This mindset became important in his reconciling Russian and European influences in his compositional style and showed that both these aspects of Russian culture were actually "intertwined and mutually dependent."[47] It would also become a starting point for other Russian composers to build their own individual styles.[48]

While Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent on the whole[49] (citing him as "a composer of genius" in his autobiography[50]), he was less pleased with the more progressive tendencies of some of Tchaikovsky's student work.[51] Nor would he change his opinion as Tchaikovsky's reputation grew in the years following his graduation.[a 3][a 4] He and Zaremba would clash with Tchaikovsky when he submitted his First Symphony for performance by the RMS in Saint Petersburg. Rubinstein and Zaremba refused to consider the work unless substantial changes were made.[52] Tchaikovsky complied but they still refused to perform the symphony.[53] Tchaikovsky, distressed that he had been treated as though he were still their student, withdrew the symphony. It would be given its first complete performance, minus the changes Rubinstein and Zaremba had requested, in Moscow in February 1868.[54]

After graduating from the Conservatory, Tchaikovsky briefly considered a return to public service due to pressing financial needs. However, Rubinstein's brother Nikolai offered the post of Professor of Music Theory at the soon-to-open Moscow Conservatory. While the salary for his professorship would be only 50 rubles a month, the offer itself boosted Tchaikovsky's morale and he accepted the post eagerly.[55] He was further heartened by news of the first public performance of one of his works, his Characteristic Dances, conducted by Johann Strauss II at a concert in Pavlovsk Park on September 11, 1865.[56] (Tchaikovsky would later include this work, retitled, Dances of the Hay Maidens, in his opera The Voyevoda.)

From 1867 to 1878, Tchaikovsky combined his professorial duties with music criticism while continuing to compose.[57] This exposed him to a range of contemporary music and afforded him the opportunity to travel abroad.[58] In his reviews, he praised Beethoven, considered Brahms overrated and took Schumann to task for poor orchestration.[59][a 5] He appreciated the staging of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen at its inaugural performance in Bayreuth, Germany, but not the music, calling Das Rheingold "unlikely nonsense, through which, from time to time, sparkle unusually beautiful and astonishing details."[60] A recurring theme he addressed was the poor state of Russian opera.[61]

Relationship with The Five

In 1856, while Tchaikovsky was still at the School of Jurisprudence and Anton Rubinstein lobbied aristocrats to form the RMS, critic Vladimir Stasov and an 18-year-old pianist, Mily Balakirev, met and agreed upon a nationalist agenda for Russian music. Taking the operas of Mikhail Glinka as a model, they espoused a music that would incorporate elements from folk music, reject traditional Western methods of musical expression and use exotic harmonic devices such as the whole tone and octatonic scales.[62] Moreover, they saw Western-style conservatories as unnecessary and antipathetic to fostering native talent; imposing foreign academics and regimentation would stifle the Russian qualities Balakirev and Stassov wished to nurture.[63] Followers trickled in. César Cui, an army officer who specialized in the science of fortifications, and Modest Mussorgsky, a Preobrazhensky Lifeguard officer, came in 1857. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, a naval cadet, followed in 1861 and Alexander Borodin, a chemist, in 1862. Like Balakirev, they were not professionally trained in composition but possessed varying degrees of musical proficiency. Together, the five composers became known as the moguchaya kuchka, translated into English as the Mighty Handful or The Five.[64]

Balakirev and Stassov's efforts fueled a debate, begun by Russian intelligentsia in the 1830s, over whether artists negated their Russianness when they borrowed from European culture or took vital steps toward renewing and developing their culture.[65] Rubinstein's criticism of amateur efforts in musical composition (he insisted that creativity without discipline was a waste of talent) and his pro-Western outlook and training fanned the flames further. His founding a professional institute where predominantly foreign professors taught alien musical practices heated the controversy to boiling.[66] Balakirev attacked Rubinstein for his musical conservatism and the Conservatory as a place where professors, dressed "in professional, antimusical togas, first pollute their students' minds, then seal them with various abominations."[67] Tchaikovsky and his fellow conservatory students were caught in the middle, well-aware of the argument but directed by Rubinstein to remain silent and focus on their own artistry.[68] Nevertheless, as Rubinstein's pupil, Tchaikovsky became a target for The Five's scrutiny and criticized for not following their precepts. [69] Cui, who would champion the nationalist cause as a music critic for the next half-century, wrote a blistering review of a cantata Tchaikovsky had composed as his graduation thesis. The review devastated the composer.[70]

In 1867, Rubinstein resigned as conductor of the RMS orchestra and was replaced by Balakirev. Tchaikovsky, now Professor of Music Theory at the Moscow Conservatory,[71] had already promised his Characteristic Dances to that ensemble but felt conflicted. He wanted to stay true to his word but had concerns over sending his composition to someone whose musical aims ran counter to his own and could thus be considered hostile.[72] Compounding the issue was Balakirev's mentoring of composers whose work Tchaikovsky did not admire.[73] He eventually sent the Dances but enclosed a request for encouragement should they not be performed.[74] Balakirev, whose influence over the other composers in The Five had meanwhile waned, may have sensed the potential for a new disciple in Tchaikovsky.[75] He replied "with complete frankness" that he considered Tchaikovsky "a fully fledged artist".[76] These letters set the tone for their relationship over the next two years. In 1869, they worked together on what became Tchaikovsky's first recognized masterpiece, the fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet, a work which The Five wholeheartedly embraced.[77] The group also welcomed his Second Symphony, subtitled the Little Russian.[78] In its orignal form, Tchaikovsky allowed the unique characteristics of Russian folk song to dictate the symphonic form of its outer movements, rather than Western rules of composition. This was a primary aim of The Five.[79] (Tchaikovsky became dissatisfied with this approach, however, made a large cut in the finale and rewrote the opening movement along Western lines when he revised the symphony seven years later.)[80]

While ambivalent about much of The Five's music, Tchaikovsky remained on friendly terms with most of its members.[81] Despite his collaboration with Balakirev, Tchaikovsky made considerable efforts to ensure his musical independence from the group as well as from the conservative faction at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.[82]

Growing fame; budding opera composer

Tchaikovsky's successes during his first years as a composer were infrequent, won with tremendous effort. The disappointments in between exacerbated a lifelong sensitivity to criticism. Also, while Nikolai Rubinstein expended considerable effort in spreading Tchaikovsky's music, he was also given to fits of rage in private with the composer in critiquing it.[83] One of these rages, later documented by Tchaikovsky, involved Rubinstein's rejection of the First Piano Concerto. The work was subsequently premiered by Hans von Bülow, whose pianism had impressed the composer during an appearance in Moscow. Eventually, Rubinstein reconsidered and took up the work.[84] Bülow would champion many other Tchaikovsky works both as pianist and conductor.[85]

Several factors helped bolster Tchaikovsky's music. One was having several first-rate artists willing to perform it, eventually including Adele Aus der Ohe, Max Erdmannsdörfer, Eduard Nápravník and Sergei Taneyev. Another was a new attitude becoming prevalent among Russian audiences. Previously, they had been satisfied with hearing virtuosos who played flashy, technically demanding but musically lightweight compositions. Increasing, they began listening not only to how something was played but also, more importantly, about the music itself.[86] Tchaikovsky's works were performed frequently, with few delays between their composition and first performances, which helped familiarize his music with the public. The publication from 1867 onwards of his songs and great piano music for the home market also helped boost the composer's popularity.[87]

During the early part of this period, Tchaikovsky began to compose operas. His first, The Voyevoda, based on a play by Alexander Ostrovsky, was premiered in 1869. The composer became dissatisfied with it and, having re-used parts of it in later works, destroyed the manuscript. Undina followed in 1870. Only excerpts were performed and it, too, was destroyed.[88] In between these, he started to compose an opera called Mandragora, to a libretto by Sergei Rachinskii. The only music he completed from this project was a short chorus of Flowers and Insects.[89]

The first Tchaikovsky opera to survive intact, The Oprichnik, premiered in 1874. During its composition, he had fallen out with Ostrovsky and had completed the libretto himself. The author of the play The Oprichnik, Ivan Lazhechnikov, had died in 1869, and Tchaikovsky decided to write the opera's libretto himself, modelling his dramatic technique on that of Eugène Scribe. Cui wrote a "characteristically savage press attack" on the opera.[88] Mussorgsky, writing to Vladimir Stasov, disapproved of the opera as pandering to the public.[88] Nevertheless, The Oprichnik continues to be performed from time to time in Russia.

The last of the early operas, Vakula the Smith (Opus 14), was composed in the second half of 1874. The libretto, based on Gogol's Christmas Eve, was to have been set to music by Alexander Serov. With Serov's death, the libretto formed the basis for a competition with a guarantee that the winning entry would be premiered by the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre. Tchaikovsky was declared the winner, but at the 1876 premiere the opera enjoyed only a lukewarm reception.[90] After Tchaikovsky's death, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote an opera based on the same story, Christmas Eve.[91]

Other works of this period include the Variations on a Rococo Theme for cello and orchestra, the Second and Fourth Symphonies, the ballet Swan Lake and the opera Eugene Onegin.

Emotional life

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time.[92] It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to homosexuality and portray him as a heterosexual to efforts at armchair analysis by Western biographers.[93] A current tendency is to discuss Tchaikovsky's personal life candidly.[94]

Tchaikovsky lived as a bachelor most of his life. In 1877, at the age of 37, he wed a former student, Antonina Miliukova.[95] The marriage was a disaster. Mismatched psychologically and sexually,[96] the couple lived together for only two and a half months before Tchaikovsky left, overwrought emotionally and suffering from an acute writer's block.[97] Tchaikovsky's family remained supportive of him during this crisis and throughout his life.[98] He was also aided by Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a railway magnate who had begun contact with him not long before the marriage. Over the next 13 years, she served as his patroness, which allowed him to focus exclusively on composition,[99] and as an important friend and emotional support in his life.[100]

Sexuality

Tchaikovsky had clear homosexual tendencies; some of the composer's closest relationships were with persons of his own sex.[101] He sought out the company of homosexuals in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them."[83] Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's sexual orientation, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it.[102]

More debatable is how comfortable the composer felt with his sexual nature. One conclusion is that he "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage."[103] Another suggests that, through "sexual overindulgence," Tchaikovsky convinced himself that he was homosexual and possibly inhibited his true sexual feelings.[104] While potentially questionable, this theory offers a companion behavior to explain one possibly unassailable fact and perhaps "the true tragedy" of the composer's personal life—that, in treating potential sexual partners as either temporary encounters or objects to idolize, he was left "unable to form an integrated, secure relationship with another man."[104] A third conclusion is that, while he experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his homosexuality, he remained aware of the negative consequences of that knowledge becoming public, especially of the ramifications for his family.[105] That family proved a loving and supportive one. While his father continued to hope Tchaikovsky would marry (and may have been clueless to his son's orientation), others remained more open-minded. Modest shared his sexual orientation and became his literary collaborator, biographer and closest confidant.[106] Tchaikovsky was eventually surrounded by an adoring group of male relatives and friends, which may have aided him in achieving some sort of psychological balance and inner acceptance of his sexual nature.[107]

The level of official tolerance Tchaikovsky may have experienced, which could fluctuate depending on the broad-mindedness of the ruling Tsar, is also open to question. One argument is that general intolerance of homosexuality was the rule in 19th century Russia, punishable by imprisonment, loss of all rights, banishment to the provinces or exile from Russia altogether; therefore, Tchaikovsky's fear of social rejection was grounded in some justification.[108] The other argument is that the Imperial bureaucracy was considerably less draconian in Tchaikovsky's lifetime than previously imagined.[109] Only the Russian Army banned homosexual acts.[110] While Nicholas I had criminalized such behavior in 1832 with the signing of Articles 995 and 996, these laws were seldom enforced—nor could they, since many prominent writers and statesmen were known homosexuals.[111] (In fact, in her research on homosexuality in Russia at the time of Tchaikovsky's death, Russian writer Nina Berberova found only one case in the 1890s that was prosecuted under either of these articles.)[112][a 6] Members of the upper classes caught in compromising positions were generally shuffled quietly from one official position to another.[110] Extreme cases were confined to their estates, sent to mental asylums or monasteries or banished either to the provinces or abroad.[113] This did not mean that there was no potential for repercussions should Tchaikovsky's sexual activities be known publicly; discretion still had to be maintained.[114] However, his enhanced social standing by the latter part of his life and the fact he was Alexander III's favorite composer may have assured that he would never endure formal prosecution or protracted scandal, even if news of indiscretion reached the Imperial family.[115]

Russian society, with its surface veneer of Victorian propriety, may have been no less tolerant than the government.[116] Homosexual behavior apparently became more visible in Russian life after Alexander II enacted liberal changes, including the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and judicial reform three years later.[117] While such displays might have caused embarrassment or bewilderment among the populace, they supposedly did not engender outright rejection of condemnation.[118] Also, the social convention of lower class people submitting to their superiors in every way, including sexually, lingered after serfdom ended.[119] Peasants, traditionally tolerant of all kinds of sexual preferences among their masters, were ready to satisfy them on demand.[120] This was also true for servants, who were used by their masters in a form of hierarchical sex.[121]

Regardless of what may be correct about Tchaikovsky or the society in which he lived, he chose not to neglect social convention and stayed conservative by nature.[122] His love life remained complicated. A combination of upbringing, timidity and deep commitment to relatives precluded him from living openly with a male lover.[123] A similar blend of personal inclination and period decorum kept him from having sexual relations with those in his social circle.[124] He sought out anonymous encounters on a regular basis, many of which he reported to Modest and for which, at times, he felt genuine remorse.[125] He also attempted to maintain some discretion and adjust his tastes to the conventions of Russian society.[126] Nevertheless, many of his colleagues, especially those closest to him, may have either known or guessed his true sexual nature.[127] Tchaikovsky's decision to enter into a heterosexual union and try to lead a double life was prompted by several factors—the possibility of exposure, the willingness to please his father, his own desire for a permanent home and his love of children and family. There is no reason however to suppose that these personal travails impacted negatively on the quality of his musical inspiration or capacity.[83]

Unsuccessful marriage

In 1868, Tchaikovsky met Belgian soprano Désirée Artôt, then touring Russia with an Italian opera company and causing a sensation with her performances in Moscow.[128] They became infatuated and were engaged to be married.[129] Even so, Artôt told Tchaikovsky that she would not give up the stage or settle in Russia.[130] Nikolai Rubinstein, fearful that living in a famous singer's shadow would stifle Tchaikovsky's creativity, warned against the union.[131] Undeterred, and while still privately preferring a homosexual lifestyle, the composer discussed wedding plans at length with his father.[132] However, on September 15, 1869, without any communication with Tchaikovsky, Artôt married a Spanish baritone in her company, Mariano Padilla y Ramos.[a 7] Although it is generally thought that Tchaikovsky swiftly got over the affair, it has been suggested that he coded Désirée's name into the Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor and the tone-poem Fatum.[133] They met on a handful of later occasions and, in October 1888, he wrote Six French Songs, Op. 65, for her, in response to her request for a single song. Tchaikovsky later claimed she was the only woman he ever loved.[134]

By the end of 1876, Tchaikovsky had fallen in love with Iosif Kotek, a former student from the Moscow Conservatory.[135] Though he wrote to Modest that Kotek reciprocated his feelings, the composer distanced himself a few months later when Kotek proved to be unfaithful.[136] At roughly the same time another friend, Vladimir Shilovsky, suddenly married. Tchaikovsky did not take the news well. He and Shilovsky, who may have also been homosexual, had shared a mutual bond of affection for just over a decade.[137] Tchaikovsky had previously mentioned the possibility of marriage to Modest, out of concern that public knowledge of his sexuality might scandalize his family.[138] Modest and their sister Sasha, in turn, had warned against such a step.[139] However, Shilovsky's wedding may have spurred him to action.[140] In doing so, he did not consider several factors. One was that his feelings on the matter may have been conflicted. While he wrote to his brother Anatoly about using marriage as a means of securing sexual freedom through leading a "double life," in the same letter he disparaged his homosexual acquaintances who had actually done so.[141] Another factor was that, at 37, Tchaikovsky might have been more set in his bachelor's ways than he would have admitted. Age alone would make that lifestyle much harder to discard or ignore than if he had married much earlier.[142]

Tchaikovsky on His Marriage

There's no doubt that for some months on end I was a bit insane and only now, when I'm completely recovered, have I learned to relate objectively to everything which I did during my brief insanity. That man who in May took it into his head to marry Antonina Ivanova, who during June wrote a whole opera as though nothing had happened, who in July married, who in September fled from his wife, who in November railed at Rome and so on—that man wasn't I, but another Pyotr Ilyich.

In July 1877, Tchaikovsky married another former student, Antonina Miliukova, after receiving a series of impassioned letters from her.[95] To ensure there would be no interference, he told only Anatoly and his father of his engagement. He did not inform Modest or Sasha until the day before his wedding or Vladimir Shilovsky until the day of the wedding. He invited only Anatoly to the ceremony.[144] Almost as soon as the wedding ended, Tchaikovsky felt he had made a mistake and soon afterwards found that he and Antonina were incompatible psychologically and sexually.[96] If Tchaikovsky attempted to explain his sexual mores to his wife, she did not understand.[145][a 8]

As time passed, Tchaikovsky may have realized that marriage itself, not simply Antonina, may have been wrong for him.[146]He wrote to Sasha that he had "become too used to bachelor life and I cannot recall my loss of freedom without regret."[147] He concluded that, instead of strengthening his personal and social standing, his marriage had actually imperiled it because of the grief and scandal that could result from its failure. Money matters and an inability to compose compounded the situation and drove Tchaikovsky to deeper levels of despair.[148] The couple lived together for only two and a half months before the mounting emotional crisis forced him to leave.[97] He traveled to Clarens, Switzerland for rest and recovery.[149] He and Antonina remained legally married but never lived together again nor had any children,[a 9] though Antonina later gave birth to three children by another man.[150]

Tchaikovsky's marital debacle may have forced him to face the full truth about his sexuality. He never blamed Antonina for the failure of their marriage[151] and he apparently never again considered matrimony or considered himself capable of loving women in the same manner as other men. He admitted to his brother Anatoly that there was "nothing more futile than wanting to be anything other than what I am by nature."[152] Also, though Tchaikovsky would confess it only in periods of deep depression, the episode left him with a deep sense of shame and guilt and an apprehension that Antonina might fully realize and publicize his sexual orientation. Those factors made each of her occasional letters "a great misfortune" which would leave him shaken for days. They also made any news of her, regardless of how minor or innocent, to cause Tchaikovsky lost sleep and appetite, an inability to work and to fixate on imminent death.[153]

Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda von Meck, the wealthy widow of a railway tycoon, was one of the growing nouveau riche patronizing the arts in the wake of Russia's industrialization. She would eventually be joined by timber merchant Mitrofan Belyayev, railway magnate Savva Mamontov and textile manufacturer Pavel Tretyakov. Von Meck differed from her fellow philanthropists in two ways. First, instead of promoting nationalist artists, she helped Tchaikovsky, who was seen as a composer of the Western-oriented aristocracy. Second, while Belyayev, Mamontov and Tretyakov made a public display of their largess, von Meck conducted her support of Tchaikovsky as a largely private matter.[154]

Nadezhda von Meck's support began through Iosif Kotek, who had been hired as a musician in the von Meck household. In 1877, Kotek suggested commissioning some pieces for violin and piano from Tchaikovsky. Von Meck, who had liked what she had heard of his music, agreed. Her subsequent request to the composer became an ongoing correspondence, even as events with Antonina unfolded and made Tchaikovsky's life increasingly difficult.[155] Von Meck and Tchaikovsky would exchange well over 1,000 letters, making theirs perhaps the most closely documented relationship between patron and artist. In these letters Tchaikovsky was more open about his creative processes than he was to any other person.[156]

Von Meck eventually paid Tchaikovsky an annual subsidy of 6,000 rubles, which would enable him to concentrate on composition.[99] With this patronage came a relationship that, while remaining epistolary, grew extremely intimate.[100] She suddenly ended the relationship in 1890. While Tchaikovsky was not in as urgent a need of her money as he had been, her friendship and encouragement had remained an integral part of his emotional life. He remained bewildered and resentful about her absence for the remaining three years of his life.[157]

Years of wandering

Tchaikovsky remained abroad for a year after the disintegration of his marriage, during which he completed Eugene Onegin, orchestrated the Fourth Symphony and composed the Violin Concerto.[158] He returned to the Moscow Conservatory in the autumn of 1879 but quickly resigned[159] and never again took up permanent residence in the city.[160] Instead, assured of a regular income from Nadezhda von Meck, he traveled incessantly throughout Europe and rural Russia. Living mainly alone, he never stayed long in any one place and avoided social contact whenever possible.[159] Tchaikovsky's troubles with with Antonina continued. She agreed to, then refused, to divorce him. At one point, she moved into an apartment directly above where he was staying during an extended visit to Moscow.[161] Tchaikovsky listed her accusations in detail to Modest: "I am a deceiver who married her in order to hide my true nature ... I insulted her every day, her sufferings at my hands were great ... she is appalled by my shameful vice, etc., etc." He may have lived the rest of his life in dread of Antonina's power to expose him publicly .[162] This could be why his best work from this period, except for the piano trio which he wrote upon the death of Nikolai Rubinstein, is found in genres which did not depend heavily on personal expression.[161]

Tchaikovsky's foreign reputation grew rapidly. In Russia, though, it was "considered obligatory [in progressive musical circles in Russia] to treat Tchaikovsky as a renegade, a master overly dependent on the West."[163] In 1880 this assessment changed. During commemoration ceremonies for the Pushkin Monument in Moscow, Dostoyevsky charged that Russian poet and playwright Alexander Pushkin had given a prophetic call to Russia for "universal unity" with the West.[163] An unprecedented acclaim for Dostoyevsky's message spread throughout Russia, and with it disdain for Tchaikovsky's music evaporated. He even drew a cult following among the young intelligentsia of Saint Petersburg, including Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst and Sergei Diaghilev.[164]

In 1880, the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour neared completion in Moscow; the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Alexander II in 1881 was imminent;[a 10] and the 1882 Moscow Arts and Industry Exhibition was in the planning stage. Nikolai Rubinstein suggested a grand commemorative piece for association with these related festivities. Tchaikovsky began the project in October 1880, finishing it within six weeks. He wrote to Nadezhda von Meck that the resulting work, the 1812 Overture, would be "very loud and noisy, but I wrote it with no warm feeling of love, and therefore there will probably be no artistic merits in it."[165] He also warned conductor Eduard Nápravník that "I shan't be at all surprised and offended if you find that it is in a style unsuitable for symphony concerts."[165] Nevertheless, this work has become for many "the piece by Tchaikovsky they know best."[166]

On March 23, 1881, Nikolai Rubinstein died in Paris. Tchaikovsky, holidaying in Rome, went immediately to attend the funeral. He arrived in Paris too late for the ceremony but was in the cortege which accompanied Rubinstein's coffin by train to Russia.[167] In December, he started work on his Piano Trio in A minor, "dedicated to the memory of a great artist."[168] The trio was first performed privately at the Moscow Conservatory on the first anniversary of his death.[169] The piece became extremely popular during the composer's lifetime and was to become Tchaikovsky's own elegy when played at memorial concerts in Moscow and Saint Petersburg in November 1893.[170]

Return to Russia

Now 44 years old, in 1884 Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. In March of that year, Tsar Alexander III conferred upon him the Order of St. Vladimir (fourth class), which carried with it hereditary nobility[171] and won Tchaikovsky a personal audience with the Tsar.[172] This was a visible seal of official approval which advanced Tchaikovsky's social standing.[171] This advance may have been cemented in the composer's mind by the great success of his Orchestral Suite No. 3 at its January 1885 premiere in Saint Petersburg, under von Bülow's direction,[173] at which the press was unanimously favorable. Tchaikovsky wrote to von Meck: "I have never seen such a triumph. I saw the whole audience was moved, and grateful to me. These moments are the finest adornments of an artist's life. Thanks to these it is worth living and laboring." .[173]

In 1885 the tsar requested a new production of Eugene Onegin to be staged at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in Saint Petersburg. (Its only other production had been by students from the Conservatory.) By having the opera staged there and not at the Mariinsky Theatre, he served notice that Tchaikovsky's music was replacing Italian opera as the official imperial art. In addition, thanks to Ivan Vsevolozhsky, Director of the Imperial Theaters and a patron of the composer, Tchaikovsky was awarded a lifetime annual pension of 3,000 rubles from the tsar. This made him the premier court composer, in practice if not in actual title.[174]

Despite his disdain for public life, Tchaikovsky now participated in it both as a consequence of his increasing celebrity and because he felt it his duty to promote Russian music.[172] He helped support his former pupil Sergei Taneyev, who was now director of Moscow Conservatory, by attending student examinations and negotiating the sometimes sensitive relations among various members of the staff.[172] Tchaikovsky also served as director of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society during the 1889-1890 season. In this post, he invited many international celebrities to conduct, including Johannes Brahms, Antonín Dvořák and Jules Massenet,[172] although not all of them accepted.

Tchaikovsky also promoted Russian music as a conductor,[172] as which he had sought to establish himself for at least a decade, believing that it would reinforce his success.[175] In January 1887 he substituted at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow at short notice for performances of his opera Cherevichki.[176] Within a year of the Cherevichki performances, Tchaikovsky was in considerable demand throughout Europe and Russia, which helped him overcome life-long stage fright and boosted his self-assurance.[177] Conducting brought him to America in 1891, where he led the New York Music Society's orchestra in his Festival Coronation March at the inaugural concert of the Carnegie Hall.[178]

In 1888 Tchaikovsky led the premiere of his Fifth Symphony in Saint Petersburg, repeating the work a week later with the first performance of his tone poem Hamlet. Although critics proved hostile, with César Cui calling the symphony "routine" and "meretricious",[179] both works were received with extreme enthusiasm by audiences, and Tchaikovsky, undeterred, continued to conduct the symphony in Russia and Europe.[180]

Belyayev circle and growing reputation

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived in Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts, devoted exclusively to the music of Russian composers. One included the first complete performance of his revised First Symphony; another featured the final version of Third Symphony of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, with whose circle Tchaikovsky was already in touch. [181] Rimsky-Korsakov, with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and several other nationalistically minded composers and musicians, had formed a group known the Belyayev circle, named after a merchant and amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher.[182] Tchaikovsky's spent much time in this circle, becoming far more at ease with them than he had been with the 'Five' and increasingly confident in showcasing his music alongside theirs.[183] This relationship lasted until Tchaikovsky's death.[184][185]

In 1892, Tchaikovsky was voted a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in France, only the second Russian to be honored so (the first was sculptor Mark Antokolski).[186] The following year, the University of Cambridge in Britain awarded Tchaikovsky an honorary Doctor of Music degree.[187]

Death

On October 30, 1893 Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique In Saint Petersburg. Nine days later, Tchaikovsky died there, aged 53. He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, near the graves of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, and Modest Mussorgsky; later, Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev were also buried nearby.[188]

While Tchaikovsky's death has traditionally been attributed to cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier.[189] some have theorized that his death was a suicide.[190] Opinion has been summarized as follows: "The polemics over [Tchaikovsky's] death have reached an impasse ... Rumor attached to the famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol. We do not know how Tchaikovsky died. We may never find out ....."[191]

Music

Tchaikovsky wrote many works which are popular with the classical music public, including his Romeo and Juliet, the 1812 Overture, his three ballets (The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty) and Marche Slave. These, along with two of his four concertos, the last three of his six numbered symphonies and, of his eight extant operas, The Queen of Spades and Eugene Onegin, are among his most familiar works. Almost as popular are the Manfred Symphony, Francesca da Rimini, the Capriccio Italien and the Serenade for Strings. His three string quartets and piano trio all contain beautiful passages, while recitalists still perform some of his 106 songs.[192] Tchaikovsky also wrote over a hundred piano works, covering the entire span of his creative life. Brown has asserted that "while some of these can be challenging technically, they are mostly charming, unpretentious compositions intended for amateur pianists."[193] He adds, however, that "there is more attractive and resourceful music in some of these pieces than one might be inclined to expect."[194]

Creative range

Tchaikovsky's formal conservatory training allowed him to write works with Western-oriented attitudes and techniques. His music showcases a wide range and breadth of technique, from a poised "Classical" form simulating 18th century Rococo elegance, to a style more characteristic of Russian nationalists, or (according to Brown) a musical idiom expressly to channel his own overwrought emotions.[195] Despite his reputation as a "weeping machine,"[192] self-expression was not a central principle for Tchaikovsky. In a letter to von Meck dated December 5, 1878, he explained there were two kinds of inspiration for a symphonic composer, a subjective and an objective one, and that program music could and should exist, just as it was impossible to demand that literature make do without the epic element and limit itself to lyricism alone. Correspondingly, the large scale orchestral works Tchaikovsky composed can be divided into two categories—symphonies in one category, and other works such as symphonic poems in the other.[196] According to musicologist Francis Maes, program music such as Francesca da Rimini or the Manfred Symphony was as much a part of the composer's artistic credo as the expression of his "lyric ego."[197] Maes also identifies a group of compositions which fall outside the dichotomy of program music versus "lyrical ego," where he hearkens toward pre-Romantic aesthetics. Works in this group include the four orchestral suites, Capriccio Italien, the Violin Concerto and the Serenade for Strings.[198]

One of the recognizable characteristics of Tchaikovsky’s works is his use of harmony or rhythm to create a sudden, powerful release of emotion. Like the other Romantic composers of the era, Tchaikovsky colored his works with rich harmonies, utilizing German Augmented Sixth chords, minor triads with added major sixths, and augmented triads. These colorful harmonies progressed to moments of extreme emotion. Though the peaks were preceded by building tension, Tchaikovsky was often criticized for his lack of development throughout his material. Yet what critics failed to accept was the fact that Tchaikovsky was not attempting to smoothly develop his works, but rather disregard seamless flow and embrace the intense emotion created by momentous bursts of fervid harmonies.[199]

Reception and reputation

Although Tchaikovsky's music has always been popular with audiences, it has at times been judged harshly by musicians and composers. However, his reputation is now generally regarded as secure. The initially criticized Swan Lake is currently seen as the first step in Tchaikovsky’s reputation as one of the most important and talented ballet composers.[200] His music has won a significant following among concert audiences that is second only to the music of Beethoven,[191] thanks in large part to what Harold C. Schonberg terms "a sweet, inexhaustible, supersensuous fund of melody ... touched with neuroticism, as emotional as a scream from a window on a dark night."[201] According to Wiley, this combination of supercharged melody and surcharged emotion polarized listeners, with popular appeal of Tchaikovsky's music counterbalanced by critical disdain of it as vulgar and lacking in elevated thought or philosophy.[191] More recently, Tchaikovsky's music has received a professional reevaluation, with musicians reacting more favorably to its tunefulness and craftsmanship.[192] Even more recent reevaluations, especially in David Brown's exhaustive four-volume critical and biographical study, have placed much more emphasis on Tchaikovsky's architectural soundness as well as his powers of melodic invention and orchestration, and he is now regarded as one of the leading and most influential composers of the second half of the nineteenth century.

Public considerations

Tchaikovsky believed that his professionalism in combining skill and high standards in his musical works separated him from his contemporaries in The Five. He shared several of their ideals, including an emphasis on national character in music. His aim, however, was to link those ideals to a standard high enough to satisfy Western European criteria. His professionalism also fueled his desire to reach a broad public, not just nationally but internationally, which he eventually did.[202]

He may also have been influenced by the almost "eighteenth-century" patronage prevalent in Russia at the time, which was still strongly influenced by its aristocracy. In this style of patronage, the patron and the artist often met on equal terms. Dedications of works to patrons were not gestures of humble gratitude but expressions of artistic partnership. The dedication of the Fourth Symphony to Nadezhda von Meck is known to be a seal on their friendship. Tchaikovsky's relationship with Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich bore creative fruit in the Six Songs, Op. 63, for which the grand duke wrote the words.[203] Tchaikovsky found no aesthetic conflict in playing to the tastes of his audiences, though it was never established that he satisfied any other tastes but his own. The patriotic themes and stylization of 18th-century melodies in his works lined up with the values of the Russian aristocracy.[204]

Compositional style

According to Brown in the New Grove (1980), Tchaikovsky's melodies ranged "from Western style to folksong stylizations and occasionally folksongs themselves."[205] His use of repetitions within these melodies generally reflect the sequential style of Western practices, which he sometimes extended at immense length, building "into an emotional experience of almost unbearable intensity."[205] He experimented occasionally with unusual meters, although more usually, as in his dance tunes, he employed a firm, essentially regular meter that "sometimes becomes the main expressive agent in some movements due to its vigorous use."[205] Tchaikovsky also practiced a wide range of harmony, from the Western harmonic and textural practices of his first two string quartets to the use of the whole tone scale in the center of the finale of the Second Symphony; the latter was a practice more typically used by The Five.[205] Since Tchaikovsky wrote most of his music for the orchestra, his musical textures became increasingly conditioned by the orchestral colors he employed, especially after the Second Orchestral Suite. Brown maintains that while the composer was grounded in Western orchestral practices, he "preferred bright and sharply differentiated orchestral coloring in the tradition established by Glinka."[205] He tends to exploit primarily the treble instruments for their "fleet delicacy,"[205] though he balances this tendency with "a matching exploration of the darker, even gloomy sounds of the bass instruments."[205]

Impact

Wiley cites Tchaikovsky as "the first composer of a new Russian type, fully professional, who firmly assimilated traditions of Western European symphonic mastery; in a deeply original, personal and national style he unified the symphonic thought of Beethoven and Schumann with the works of Glinka, and transformed Liszt's and Berlioz's achievements in depictive-programmatic music into matters of Shakespearean elevation and psychological import."[206]

Holden maintains that Tchaikovsky was the first legitimate professional Russian composer, stating that only traditions of folksong and music for the Russian Orthodox Church existed before Tchaikovsky's birth. Holden continues, "Twenty years after Tchaikovsky's death, in 1913, Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring erupted onto the musical scene, signalling Russia's arrival into 20th century music. Between these two very different worlds Tchaikovsky's music became the sole bridge."[207]

Russian musicologist Solomon Volkov maintains that Tchaikovsky was perhaps the first Russian composer to think seriously about his country's place in European musical culture.[208] As the composer wrote to Nadezhda von Meck from Paris,

How pleasant it is to be convinced firsthand of the success of our literature in France. Every book étalage displays translations of Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Dostoyevsky ... The newspapers are constantly printing rapturous articles about one or another of these writers. Perhaps such a time will come for Russian music as well![209]

Tchaikovsky became the first Russian composer to personally acquaint foreign audiences with his own works, as well as those of other Russian composers.[210] He also formed close business and personal ties with many of the leading musicians of Europe and the US. For Russians, Volkov asserts, this was all something new and unusual.[211]

Finally, the impact of Tchaikovsky's own works, especially in ballet, should not be underestimated; his mastery of danseuse (melodies which match physical movements perfectly), along with vivid orchestration, effective themes and continuity of thought were unprecedented in the genre,[212] setting new standards for the role of music in classical ballet.[213] Noel Goodwin characterized Swan Lake as "one of [ballet's] enduring masterworks"[213] and The Sleeping Beauty as "the supreme example of 19th century classical ballet,"[214] while Wiley called the latter work "powerful, diverse and rhythmically complex."[215]

References

- Notes

- ^ Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский, romanized: Pëtr Il'ich Chaikovskiy IPA: [ˈpʲɵtr ɪlʲˈjitɕ tɕɪjˈkofskʲɪj] ; often "Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky" /ˈpiːtər ˈɪl[invalid input: 'ɨ']tʃ tʃaɪˈkɒvski/ in English. His names are also transliterated "Piotr" or "Petr"; "Ilitsch", "Il'ich" or "Illyich"; and "Tschaikowski", "Tschaikowsky", "Chajkovskij" and "Chaikovsky" (and other versions; the transliteration varies among languages). The Library of Congress standardized the usage Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky.

- ^ Russia was still using old style dates in the 19th century, rendering his lifespan as April 25, 1840 – October 25, 1893. Some sources in the article report dates as old style rather than new style. Dates are expressed here in the same style as the source from which they come.

- ^ Tchaikovsky ascribed Rubinstein's coolness to a difference in musical temperaments. Rubinstein could have been jealous professionally of Tchaikovsky's greater impact as a composer. Homophobia might have been another factor (Poznansky, Eyes, 29).

- ^ An exception to Rubinstein's antipathy was the Serenade for Strings, which he declared "Tchaikovsky's best piece" when he heard it in rehearsal. "At last this St. Petersburg pundit, who had growled with such consistent disapproval at Tchaikovsky's successive compositions, had found a work by his former pupil which he could endorse," according to Tchaikovsky biographer David Brown (Brown, Wandering, 121).

- ^ His critique led Tchaikovsky to consider rescoring Schumann's symphonies, a project he never realized (Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 79).

- ^ A man named Langavoy, who taught at an elite boys' school, was accused by the parents of several students. The press reported the scandal. Langavoy was tried and convicted for having relations with a 13-year-old boy and was sent to the provincial town of Saratov. Five years later, he received amnesty. The school rehired him to his former post (Karlinsky, 352).

- ^ The marriage may have been instigated by Artôt's mother, who accompanied the soprano on tour and may have learned of Tchaikovsky's sexual orientation. (Polyansky, Eyes, 79.)

- ^ This might have not been Tchaikovsky's or Antonina's fault. Victorian practices in discussing sexual matters were euphemistic and allusive. This may have left Tchaikovsky bereft of a way to communicate accurately his situation and Antonina a way to comprehend accurately, if at all, what he might have been trying to tell her (Holden, 126; Poznansky, Quest, 222).

- ^ Poznansky suggests that the marriage may never have been consummated (Poznansky, Quest, 222).

- ^ Celebration of this anniversary did not take place as Alexander II was assassinated in March 1881.

- References

- ^ Holden, 4.

- ^ a b c Poznansky, Eyes, 1.

- ^ Brown, Early, 19; Poznansky, Eyes, 1.

- ^ Holden, 5.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 6.

- ^ Holden, 6, 13; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 18.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 2.

- ^ Holden, 31.

- ^ Holden, 202.

- ^ a b Holden, 43.

- ^ Brown, Early, 22; Holden, 7.

- ^ Holden, 7.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 6.

- ^ Brown, Early, 27; Holden, 6-8

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 5.

- ^ Brown, Early, 25-26; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 7.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 7.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 6.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 6.

- ^ Maes, 33.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 8.

- ^ Brown, Early, 31; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 8.

- ^ Holden, 14; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 26.

- ^ Holden, 20.

- ^ Poznansky (1991), 11-12

- ^ Holden (1995), 15

- ^ Brown, Early Years, 47; Holden, 23.; Warrack, 29.

- ^ a b As quoted in Holden, 23.

- ^ Brown, Early Years, 46.

- ^ a b Holden, 23.

- ^ Holden, 24, 26.; Poznansky, Quest, 32–37.; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 30

- ^ Holden, 24.

- ^ Holden, 24; Poznansky, Quest, 26

- ^ As quoted in Holden, 25.

- ^ Holden, 24-25; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 31.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 17.

- ^ Holden, 25; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 31.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 23.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 14.

- ^ Brown, Early, 60

- ^ Maes, 35.

- ^ Maes, 31.

- ^ Volkov, 71.

- ^ Maes, 35; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 36.

- ^ Holden, 38–39.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 20; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 36–38.

- ^ Figes, xxxii; Volkov, 111-12.

- ^ Hosking, 347.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 47&ndash8.

- ^ Rubinstein, 110.

- ^ Brown, Early, 76; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 35.

- ^ Brown, Early, 100.

- ^ Brown, Early, 101.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:608.

- ^ Brown, Early, 82.

- ^ Brown, Early, 83.

- ^ Holden, 83; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 61.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 87.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 79.

- ^ As quoted in Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 95.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 77.

- ^ Figes, 178-81.

- ^ Maes, 8-9; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 27.

- ^ Garden, New Grove (2001), 8:913.

- ^ Bergamini, 318-19; Hosking, 274-9.

- ^ Maes, 36; Wiley, 30.

- ^ Ridenour, Nartionalism, Modernism and Personal Rivalry, 81. As quoted in Maes, 39.

- ^ Maes, 42.

- ^ Holden, 52.

- ^ Brown, Early Years, 84, 95-96.

- ^ Holden, 64.

- ^ Holden, 62.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 49.

- ^ Holden, 62.

- ^ Maes, 44.

- ^ Brown, Early, 128; Holden, 63.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: Man and Music, 49.

- ^ Brown, Early, 255.

- ^ Brown, Early, 265; Poznansky, Quest, 156.

- ^ Brown, Early, 259.

- ^ Maes, 49.

- ^ Holden, 51–52.

- ^ a b c Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:147.

- ^ Steinberg, Concerto, 474-6.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:161.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:154.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:153.

- ^ a b c Taruskin, 665.

- ^ Mandragora (at www.tchaikovsky-research.net)

- ^ Brown, Viking, 1086.

- ^ Maes, 171.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, xvi.

- ^ Maes, 133–4; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, xvii.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, xvii.

- ^ a b Brown, Crisis, 137-47; Polayansky, Quest, 207-8, 219-20; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 147-50.

- ^ a b Brown, Crisis, 146-8; Poznansky, Quest, 234; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 152.

- ^ a b Brown, Crisis, 157; Polyansky, Quest, 234; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 155.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:147.

- ^ a b Brown, Man and Music, 171–172.

- ^ a b Holden, 159, 231–32.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, all.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 8, 24, 77, 82103–105, 165–168. Also see P.I. Chaikovskii. Al'manakh, vypusk 1, (Moscow, 1995).

- ^ Poznansky, as quoted in Holden, 394.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

zajaczkowskiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Holden, 82, 162; Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:147.

- ^ Taruskin, New Grove Dictionary of Opera; Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:147.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 168; Taruskin, New Grove Dictionary of Opera.

- ^ Brown, Early, 50; Hanson and Hanson, 123; Karlinsky, 350.

- ^ Maes, 134; Poznansky, Eyes, 77.

- ^ a b Poznansky, Eyes, 77.

- ^ Karlinsky, 349; Poznansky, Eyes, 77, Quest, 137.

- ^ Karlinsky, 352.

- ^ Poznansky, Last, 3.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 482–3.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 243, Quest, 482–3; Volkov, 96.

- ^ Maes, 134.

- ^ Karlinsky, 350; Poznansky, Eyes, 77.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 138.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 77; Quest, 465.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 77&ndash8, Quest, 465; Taruskin, New Grove Dictionary of Opera.

- ^ Poznansky, Last, 6.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 78.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 362.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 466.

- ^ Hanson and Hanson, 165–6; Poznansky, Eyes, 185–8, Quest, 362, 421–2, 469–70; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 88.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 165.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 176.

- ^ brown, Early, 156; Poznansky, Eyes, 88.

- ^ Brown, Early Years, 156–157; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 53.

- ^ Brown, Early, 158.

- ^ Brown, Early, 158; Polyansky, Eyes, 78.

- ^ Polyansky, Eyes, 78.

- ^ Brown, Early, 197–200.

- ^ "Artôt, Désirée (1835–1907)". Schubertiade music. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 103; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 102-3.

- ^ Poznansky, Eyes, 103, 105; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 102-3.

- ^ Brown, Crisis, 138; Poznansky, Eyes, 76&ndash7, Quest, 95, 126, 204.

- ^ Holden, 113; Poznansky, Quest, 186; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 88.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 184; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 88–9.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 204.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 185.

- ^ Poznansky,Quest, 204; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 151.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Crisis, 254.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 216–218, 220; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 149.

- ^ Holden, 126; Poznansky, Quest, 222; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 112.

- ^ Holden, 126; Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 152.

- ^ As quoted in Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 152.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 234.

- ^ Holden, 126, 145, 148, 150.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 230, 232; Holden, 209.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 120.

- ^ Letter to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, February 25, 1878. As quoted in Holden, 172

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 235, 245–6.

- ^ Figes, 195–197; Maes, 173–174, 196–197.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 129–130.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 134; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 108, 130–33.

- ^ Brown, Final, 287–289; Holden, 293; Poznansky, Quest, 521, 526; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 242.

- ^ Wiley, Tchaikovsky, 159, 170, 193.

- ^ a b Brown, Man and Music, 219.

- ^ "Moscow". www.tchaikovsky-research.net. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ a b Brown, New Grove, 18:619.

- ^ Holden, 155

- ^ a b Volkov, 126.

- ^ Volkov, 122–123.

- ^ a b As quoted in Brown, Wandering, 119.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 224.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 172

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Wandering, 151.

- ^ Brown, Wandering, 151.

- ^ Brown, Wandering, 152.

- ^ a b Brown, New Grove, 18:621; Holden, 233.

- ^ a b c d e Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:162.

- ^ a b Brown, Man and Music, 275.

- ^ Maes, 140.

- ^ Brown, Crisis Years, 133.

- ^ Holden, 261; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 197.

- ^ Holden, 266; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 232.

- ^ Brown, Final, 319–320

- ^ Holden, 272.

- ^ Holden, 273.

- ^ Brown, Final Years, 90-1

- ^ Maes, 173

- ^ Brown, Final, 92.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 564.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 308.

- ^ Poznansky, Quest, 548-549.

- ^ Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 264.

- ^ Brown, Final, 487.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 430–32; Holden, 371; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 269–270.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 431–35; Holden, 373–400.

- ^ a b c Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:169.

- ^ a b c Schonberg, 367.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 118.

- ^ Brown, The Final Years, 408.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:606.

- ^ Wood, 75.

- ^ Maes, 154.

- ^ Maes, 154–155.

- ^ Zajaczkowski 25

- ^ Brown, 2007, 117

- ^ Schonberg, 366.

- ^ Maes (2002), 73.

- ^ Maes, 139–141.

- ^ Maes, 137.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown, New Grove (1980), 18:628.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:144.

- ^ Holden, xxi.

- ^ Volkov, Solomon, St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1995)126.

- ^ Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. Literaturnye proizvedeniia i perepiska (Complete Collected Works. Literary Works and Correspondence), vol 13 (Moscow, 1971), 349. As quoted in Volkov, 126.

- ^ Warrack, 209.

- ^ Volkov, 126

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:152–153.

- ^ a b Goodwin, New Grove (1980), 5:205.

- ^ Goodwin, New Grove (1980), 5:206–207.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:165.

- Sources

- Abraham, Gerald,(Ed.), Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1946). ISBN n/a. OCLC 385829

- Lockspeiser, Edward, "Tchaikovsky the Man"

- Cooper, Martin, "The Symphonies"

- Blom, Eric, "Works for Solo Instrument and Orchestra"

- Wood, Ralph W., "Miscellaneous Orchestral Works"

- Mason, Colin, "The Chamber Music"

- Dickinson, A.E.F., "The Piano Music"

- Abraham, Gerald, "Operas and Incidental Music"

- Evans, Edwin, "The Ballets"

- Alshvang, A., tr. I. Freiman, "The Songs"

- Abraham, Gerald, "Religious and Other Choral Music"

- Bergamini, John, The Tragic Dynasty: A History of the Romanovs (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969). Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 68-15498.

- Brown, David, ed. Stanley Sadie, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich", The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Brown, David, ed. Amanda Holden, with Nicholas Kenyon and Stephen Walsh, "Pyotr Tchaikovsky", The Viking Opera Guide (London: Viking, 1993), ISBN 0-670-81292-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840–1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874–1878, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878–1885, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986). ISBN 0-393-02311-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991). ISBN 0-393-03099-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007). ISBN 0-571-23194-2.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.).

- Goodwin, Noel, ed. Stanley Sadie, "Dance: VI. 19th Century, (iv) The classical ballet in Russia to 1900", The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillan, 1980), 20 vols. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Hanson, Lawrence and Hanson, Elisabeth, Tchaikovsky: The Man Behind the Music (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 66–13606.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Hosking, Geoffrey, Russia and the Russians: A History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-674-00473-6.

- Jackson, Timothy L., Tchaikovsky, Symphony no. 6 (Pathétique) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). ISBN 0-521-64676-6.

- Karlinsky, Simon, "Russia's Gay Literature and Culture: The Impact of the October Revolution." In Hidden from history: reclaiming the gay and lesbian past (New York: American Library, 1989), ed. Duberman, Martin, Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey. ISBN 0-452-01067-5.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Mochulsky, Konstantin, tr. Minihan, Michael A., Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 65–10833.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 0-02-871885-2.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky's Last Days: A Documentary Study (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-198-16596-X.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky Through Others' Eyes. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999). ISBN 0-253-33545-0.

- Ridenour, Robert C., Nationalism, Modernism and Personal Rivalry in Nineteenth-Century Russian Music (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981). ISBN 0835711625.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai, Letoppis Moyey Muzykalnoy Zhizni (St. Petersburg, 1909), published in English as My Musical Life (New York: Knopf, 1925, 3rd ed. 1942). ISBN n/a.

- Rubinstein, Anton, tr. Aline Delano, Autobiography of Anton Rubinstein: 1829-1889 (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1890). Library of Congress Control Number 06004844.

- Schonberg, Harold C. Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. 1997). ISBN 0-393-03857-2.

- Steinberg, Michael, The Concerto (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Steinberg, Michael, The Symphony (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Taruskin, Richard, ed. Stanley Sadie, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il'yich", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, vol. 4 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 978-0-19-522186-2.

- Tchaikovsky, Modest, Zhizn P.I. Chaykovskovo [Tchaikovsky's life], 3 vols. (Moscow, 1900–1902).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, Perepiska s N.F. von Meck [Correspondence with Nadzehda von Meck], 3 vols. (Moscow and Lenningrad, 1934–1936).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, Polnoye sobraniye sochinery: literaturnïye proizvedeniya i perepiska [Complete Edition: literary works and correspondence], 17 vols. (Moscow, 1953–1981).

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Bouis, Antonina W., St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1995). ISBN 0-02-874052-1.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78–105437.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). SBN 684-13558-2.

- Wiley, Roland John, Tchaikovsky's Ballets (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). ISBN 0-198-16249-9.

- Wiley, Roland John, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillian, 2001). ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Wiley, Roland John, The Master Musicians: Tchaikovsky (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0-19-536892-5.

- Zajaczkowski, Henry, Tchaikovsky's Musical Style (Russian Music Studies, 19). Ann Arbor, MI: Umi Research Pr, 1987.

External links

- Tchaikovsky Research

- Tchaikovsky performances on ClassicalTV

- Tchaikovsky cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Turgenev and Tchaikovsky (with music samples)

- Gay Love-Letters from Tchaikovsky to his Nephew Bob Davidov

- Music Analysis. Aspects on sexuality and structure in the later symphonies of Tchaikovsky.

Public domain sheet music

- Mutopia Project Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Mutopia

- Free scores by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Template:WIMA

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- 1840 births

- 1893 deaths

- Ballet composers

- Classical composers of church music

- Opera composers

- Composers for piano

- Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society

- Imperial School of Jurisprudence alumni

- Moscow Conservatory faculty

- LGBT Christians

- LGBT musicians from Russia

- LGBT composers

- LGBT people from Russia

- People from Votkinsk

- Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th class

- Romantic composers

- Russian ballet

- Russian composers

- Russian monarchists

- Russian music critics

- Russian Orthodox Christians

- Russian people of French descent

- Russian people of Ukrainian descent

- Saint Petersburg Conservatory alumni

- Russian music educators