Eraserhead

| Eraserhead | |

|---|---|

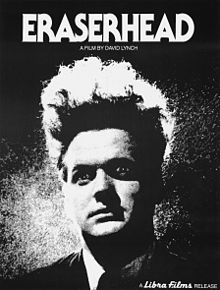

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lynch |

| Written by | David Lynch |

| Produced by | David Lynch |

| Starring | Jack Nance Charlotte Stewart Jeanne Bates |

| Cinematography | Herbert Cardwell Frederick Elmes |

| Edited by | David Lynch |

| Music by | David Lynch |

| Distributed by | Libra Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes 109 minutes (Original cut) |

| Country | Template:Film US |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20,000 (estimated) [1] |

| Box office | $7,000,000[2] |

Eraserhead is a 1977 American surrealist film[3][4][5] and the first feature film of David Lynch, who wrote, produced and directed. Lynch began working on the film at the AFI Conservatory, which gave him $10,000 to make the film after he had begun working there following his 1971 move to Los Angeles. The budget was not sufficient to complete the film and, as a result, Lynch worked on Eraserhead intermittently, using money from odd jobs and from friends and family, including childhood friend Jack Fisk, a production designer and the husband of actress Sissy Spacek, until its 1977 release.

Eraserhead polarized and baffled many critics and film-goers, but has become a cult classic.[6] In 2004, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. Lynch has called it a "dream of dark and troubling things"[7] and his "most spiritual movie."[8]

Plot

Eraserhead is set in the heart of an industrial center in a nameless city, rife with urban decay. Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) is a printer who is "on vacation" for the duration of the story. The film begins with the mysterious "Man in the Planet" (Jack Fisk) manipulating large mechanical levers while looking out of his window. As he does so, a ghostly flagellate-like creature emerges from the mouth of Henry, floating in space. The creature eventually flies away amidst images of rock formations, a circular opening, and bubbling fluid.

In the industrial center, Henry stumbles through the seemingly-unpopulated industrial wasteland to his apartment building with a bag of groceries. On his way in, a neighbour he is not familiar with, the "Beautiful Girl Across the Hall" (Judith Anna Roberts), tells him that his estranged girlfriend Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) has invited him to dinner with her and her family. In Henry's one room apartment, a sharp, distorted hissing noise (presumably the radiator) is continuously heard, large clumps of cut grass lie on the floor, a dead tree sapling planted in a pile of dirt sits directly on his nightstand, and a framed picture of a nuclear explosion hangs on the wall. The only window in his apartment faces the brick wall of another building.

That evening, Henry arrives at Mary's home, as invited. Henry is disturbed by the awkward conversation forced by Mary's mother (Jeanne Bates) as well as a strange fit Mary has; her mother reacts to it by furiously brushing her daughter's hair. At the dinner table, he is puzzled by an emotional outburst by Mary's mother, the banal, disconnected conversation offered by her father (Allen Joseph), and a miniature "man-made" roasted chicken he is given to carve, which kicks on his plate and gushes a dark liquid at the fork's touch. The dinner conversation at Mary's house is strained and awkward. Henry is later cornered by Mary's mother, who attempts to kiss him before telling him that Mary has just given birth extremely prematurely. A tearful Mary insists that it's unknown whether what she gave birth to was actually a baby, but her mother insists that it is a baby and that Henry is obliged to marry her.

Mary and the baby move into Henry's one-room apartment. The baby is hideously deformed and very inhuman-like: its face resembles a large snout with slit nostrils, a long, pencil-thin neck, eyes on the sides of its head, no ears, glossy skin and a limbless body wrapped in bandages. Henry and Mary constantly struggle with caring for the baby as it refuses to eat and continually whines throughout the night.

One night, a hysterical Mary temporarily leaves for home due to her inability to sleep with the constantly-whining baby in the room. She demands that Henry take good care of the baby. After the baby falls silent, Henry checks its temperature. Looking away briefly to read the thermometer, Henry looks back at the baby to find that it is covered with sores and gasping for breath. Left to care for the baby by himself, Henry becomes involved in a series of strange events (many of which have little to no explanation to how or why they happen). These include bizarre encounters with the "Lady in the Radiator" (Laurel Near); visions of the Man in the Planet, and a sexual liaison with the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall. The Lady in the Radiator is a miniature woman with grotesquely distended cheeks who appears in his radiator, performing dance routines and singing on a miniature stage. Henry has a dream where his head pops off and his baby's head comes up from between his shoulders, replacing it. Henry's head sinks into a growing pool of blood on a tile floor, falls from the sky, and, finally, lands on an empty street in the industrial wasteland and cracks open. A young boy finds Henry's broken head and takes it to a pencil factory, where the head is taken to a back room, and his brain is determined to be a serviceable material for pencil erasers. The boy is paid for bringing in Henry's head, and the Pencil Machine Operator sweeps the eraser shavings off the desk and sends them billowing into the air.

After waking from this dream, Henry seeks out the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall, but discovers that she is not home. The baby begins to cackle mockingly, and, shortly thereafter, Henry opens his door and sees the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall bringing another man back to her apartment. She looks at Henry, but is frightened by a vision of Henry's head transforming into that of the baby. A disappointed Henry goes back into his apartment. Upon hearing the baby whine, he retrieves a pair of scissors. He hesitates, then cautiously cuts open the bandages wrapped around the baby's body. Henry finds that the swaddling was the only thing containing the baby's internal organs; its body splits open and the vital organs are exposed. As the baby gasps in pain, a horrified Henry stabs its organs with the scissors. Rather than dying, however, the baby continues to convulse in pain, and Henry turns away in disgust. Large amounts of liquid gush forth from the organs, followed by huge quantities of a foamy substance that completely covers the baby's body. Henry watches in horror as the apartment’s electricity suddenly overloads, causing the lights to flicker on and off. The baby's neck extends to an extraordinary length, causing it to strongly resemble the flagellate creatures seen at the beginning the film. A giant apparition of its head then materializes in the apartment and approaches Henry. The lights burn out, and the head is replaced by a strange "planet". The side of the hollow planet bursts open, and through the hole, the Man in the Planet is seen struggling with a series of levers, with sparks shooting from them, burning his face. The last scene features Henry being embraced by the Lady in the Radiator. They are bathed in white light, white noise builds to a crescendo, then stops as the screen goes black.

Cast

- Jack Nance as Henry Spencer, a vacationing printer who lives alone in a small apartment. His only forms of entertainment are a record player and a fetish for dirt, plants, and worms. Henry is taciturn, but uses short, emotional outbursts when he does speak.

- Charlotte Stewart as Mary X, Henry's girlfriend, though he has not seen her for some time when the story begins. She lives with her parents and catatonic grandmother until she marries Henry and moves in with him for a short time.

- Allen Joseph and Jeanne Bates as Mr. and Mrs. X, Mary's parents. Mr. X is a pipe-fitter who boasts loudly to Henry about his role in plumbing the neighborhood and is seemingly oblivious to the emotional situation surrounding Mary's strange pregnancy and childbirth. Mrs. X, however, experiences frequent outbursts while Henry is visiting their home and eventually demands accountability of Henry.

- Judith Anna Roberts as the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall, who lives in the apartment across from Henry's and delivers the telephone message inviting Henry to dinner at Mary X's house at the beginning of the story. She serves as an object of desire for Henry.

- Laurel Near as the Lady in the Radiator, appears to Henry in several visions. She has extremely bloated cheeks and performs song and dance routines on a checkered tile stage. In one such routine she stomps on strange flagellate creatures that fall onto her stage while she is dancing.

- Jack Fisk as the Man in the Planet, seen manipulating mechanical levers while observing Henry through a window at the beginning of the film, appearing to introduce an amphibious being into the world. He is apparently responsible for the bizarre events that occur throughout the film, although it is unknown why. Later in the film, after Henry kills the baby, the Man in the Planet appears again, this time struggling with the levers.

- Darwin Joston as Paul, the desk clerk at the pencil factory.

- T. Max Graham as The Boss, the owner of the pencil factory.

- Hal Landon Jr. as Pencil Machine Operator

Production

Eraserhead developed from Gardenback, a script about adultery that Lynch wrote during his first year at the Centre for Advanced Film Studies at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles.[9] The script for Eraserhead was only 21 pages long. Because of the film's unusual plot and Lynch's minimal directorial experience, no film studio backed the project. Lynch eventually won a grant from AFI, and shot most of the film at Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills, which was at the time the Institute's headquarters.[10] During the film's production, Lynch began experimenting with an audio technique consisting of reciting lines which were spoken phonetically backwards, and playing this recording in reverse. Although the technique did not see use in Eraserhead, Lynch later returned to it for his 1990 television series Twin Peaks.[11]

Aside from the AFI grant, the film was financed by friends and family, including actress Sissy Spacek, wife of Lynch's childhood friend Jack Fisk. Because of the lack of reliable funds, Eraserhead was filmed intermittently from 1971 to 1976,[10] with sets disassembled and reassembled several times.

Release

Ben Barenholtz, the founder of Libra Films, watched the film a few weeks after its Filmex opening, and before the film was at its midway point, had decided it was a "film of the future".[12] By that summer (1977), Lynch and his wife had arrived in New York and were staying at Barenholtz's apartment; Lynch then spent two months working with a lab to get a print of the film ready for its New York opening.[12] The film opened in fall 1977 at the Cinema Village for a midnight show,[12] and eventually "became a hit on the horror circuit in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and London."[10]

Home media

Until recently, the only way to acquire Eraserhead as a Region 1 (North America) DVD was to purchase it through Lynch's own website. The version of the film on the official Region 1 DVD was remastered for the medium by Lynch himself. Customers who ordered the film from Lynch's website received the disc packaged in a special presentation box.[citation needed] The DVD included a deleted scene and a 90-minute documentary about the making of the film, which consists of Lynch sitting before a microphone, smoking cigarettes, and talking about his memories of making the film (almost like a director's commentary track, but with video). During the piece he also calls Catherine Coulson and they reminisce together about the making of the film. On January 10, 2006, Eraserhead was made commercially available by Subversive Cinema. This re-release had normal DVD packaging instead of the large boxset from David Lynch's website, but the content on the disc itself was the same. The UK DVD release is region-free, as is the Korean DVD release.[13] On October 20, 2008, the film was re-released in Region 2 in the UK, alongside a Region 2 release of The Short Films of David Lynch.[14] The film has been released on Region 4 in Australia on two separate occasions: firstly, in 2001, the film was released by Umbrella Entertainment however was discontinued approximately 3–4 years later. In 2009, it was re-released in a 'Special Edition' format and remastered by the same distribution company. Umbrella Entertainment was supposed to release it on the Blu-ray format on September 1, 2011, but got delayed due to reasons beyond their control. David Lynch is personally putting the final touches on this special high definition title, which is now due to come out in early 2012.[15] Meanwhile, the film saw its worldwide Blu-ray premiere in a German release by Capelight Pictures in March 2012[16], which was also supervised by the director.

Reception

A 1977 review of Eraserhead by Variety panned the film, describing it as a "sickening bad-taste exercise" which "pulls out all gory stops in the unwatchable climax", and adding that "the mind boggles to learn that Lynch labored on this pic for five years". However, the review praised the film's production values, especially its sound production.[12][17]

In a December 2007 review of a new 35mm print, Manohla Dargis of The New York Times called it an "amazing, still mysterious work" which "brings together many of the now-familiar Lynchian visual themes and narrative figures, including the naïve man, the slatternly woman, the shabby period furniture, the contorted flesh and forms, the yawning orifices and oozing, leaking fluids."[18] In 2003, Entertainment Weekly ranked the film fourteenth on their list of "The Top Cult Movies", stating that "Eraserhead is about that which can't be described".[19] The film currently holds a 90% "Certified Fresh" rating from review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 41 reviews.[20]

After seeing the film, Mel Brooks hired Lynch to direct The Elephant Man in 1980.[21] Eraserhead was one of director Stanley Kubrick's favorite films.[22] Before beginning production on The Shining, Kubrick screened Eraserhead for the cast to put them into the atmosphere he wanted to convey. George Lucas was a fan of the film and, after seeing it, wanted to hire Lynch to direct Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi. Lynch declined, fearing it would be less his own vision than Lucas's.[23] The directorial duties eventually went to Richard Marquand. John Waters mentioned in the documentary Midnight Movies that he is a fan of the film and, while doing promotional interviews for his own film Female Trouble, he would mention Eraserhead and David Lynch to reporters.

Lynch has said that the film's protagonist is "living under the influence of those things that existed for me in Philadelphia",[24] adding that "there was a sense of dread pretty much everywhere I went. I didn't live in any good parts of Philadelphia, and so dread was my general feeling. I hated it. And, also, I loved it". Lynch also wrote a short chapter about the film in his 2006 book Catching the Big Fish. In that book, he wrote "Eraserhead is my most spiritual movie. No one understands when I say that, but it is".[8] He went on to write about the difficulties he was having making sense of the way the film was "growing" and didn't know "the thing that just pulled it all together". He then reveals it was the Bible that provided the solution, stating "so I got out my Bible and I started reading. And one day, I read a sentence. And I closed the Bible, because that was it; that was it. And then I saw the thing as a whole. And it fulfilled this vision for me, 100 percent". Lynch states in the book that he doesn't think he will ever reveal what the vision-fulfilling Biblical verse is.

Legacy

Poet and author Charles Bukowski referenced the film when interviewed on the subject of cable television. Bukowski said, "We got cable TV here, and the first thing we switched on happened to be Eraserhead. I said, 'What’s this?' I didn’t know what it was. It was so great. I said, 'Oh, this cable TV has opened up a whole new world. We’re gonna be sitting in front of this thing for centuries. What next? So starting with Eraserhead we sit here, click, click, click — nothing."[25]

A number of rock bands take their name from the film: the 1980s London punk rock group Erazerhead; the Northern California band Eraserhead, and The Eraserheads, a rock band from the Philippines.[26] The band Henry Spencer take their name from the main character.

Apartment 26 are named after Henry's address and they feature a sample from the Lady in the Radiator's In Heaven at the end of their song, Heaven. The 1980s London indie rock band Henry's Final Dream also owe their name to this film.

Bruce McCulloch, from Canadian sketch group The Kids in the Hall, has recorded a song titled (and about) Eraserhead on his album Shame Based Man.

In Heaven, the song sung by the Lady in the Radiator, has been covered by, Bauhaus, Devo, Miranda Sex Garden, Tuxedomoon, The Danse Society, Pankow, Pixies, Desolation Yes, Bang Gang, Zola Jesus and Forgotten Sunrise. Indie rockers Modest Mouse borrowed lines from In Heaven for Workin' on Leavin' the Livin', as did the anarcho-punk band Rubella Ballet for their song Slant and Slide. The Dead Kennedys reference the film in the song Too Drunk to Fuck in the line "You bawl like the baby in Eraserhead". An Eraserhead T-shirt was available from the band's label Alternative Tentacles for some years, and even the official soundtrack.

Eraserhead, along with five other low-budget films from the 1960s and 1970s (The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Pink Flamingos, El Topo, The Harder They Come and Night of the Living Dead), was the subject of a 2005 documentary, Midnight Movies: From the Margin to the Mainstream.[27] Lynch was interviewed for the documentary.

Footnotes

- ^ "Eraserhead". IMDB. Retrieved January 1 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Eraserhead". The Numbers. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "DVD Review: Eraserhead and The Short Films of David Lynch". uncut.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ "Total Film: 11 Movies That Should Be Musicals". totalfilm.com. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Eraserhead:Overview". Allmovie. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ Peary, Danny. Cult Movies, Delta Books, 1981. ISBN 0-517-20185-2

- ^ Cinefantastique Barry Gifford Interview from lynchnet.com

- ^ a b Lynch, David (2006). Catching the Big Fish. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin Group. ISBN 1-58542-540-0.

- ^ Olsen, p.89

- ^ a b c Woodward, Richard B. (1990-01-14). "A Dark Lens on America". The New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Rodley and Lynch, pp.165–167

- ^ a b c d Hoberman, J. (1991). "Chapter 8". Midnight Movies. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80433-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Eraserhead (Korean Version)".

- ^ DVD Times - Eraserhead & David Lynch Short Films (R2) in October from dvdtimes.co.uk

- ^ "Postponed Release of Eraserhead on Blu-Ray | Filmbiz Noticeboard". Filmink.com.au. 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Staff (1977). "Variety Reviews - Eraserhead - Film Reviews". Variety. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Distorted, Distorting and All-Too Human, a December 2007 review from The New York Times

- ^ Staff (May 23, 2003). "The Top Cult Movies | Michael Jackson Remembered | EW.com". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Eraserhead - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ "The Late Late Show, Feb. 26, 1997 - Interview with David Lynch".

- ^ Ciment, Michel. Kubrick: The Definitive Edition. Faber & Faber, 2003. ISBN 0-571-21108-9

- ^ David Lynch interview 1985

- ^ "A Fish in the Percolator". Philadelphia Weekly. 2001-03-14.

- ^ "Gin-Soaked Boy - Charles Bukowski interviewed by Chris Hodenfield". Archived from the original on 2006-08-24.

- ^ Eraserhead "Alternative Rock-N-Roll"

- ^ Midnight Movies: From the Margin to the Mainstream at IMDb

References

- Hoberman, J.; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1991). "Eraserhead". Midnight Movies. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80433-6.

- Fischer, Christian (2007). Traumkino – Zu Eraserhead von David Lynch (in German). Verlag Dr. Kovac. ISBN 3-8300-2692-7.

- Olson, Greg (2008). David Lynch: Beautiful Dark. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-5917-3.

- Rodley, Chris; Lynch, David (2005). Lynch on Lynch (2nd ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 0-571-22018-5.