Entertainment

Entertainment is an action, event, or activity that aims to amuse and interest an audience. It is the audience that turns a private recreation or leisure activity into entertainment. The audience may have a passive role, as in the case of persons watching a play, opera, television show, or film; or the audience role may be active, as in the case of games. Entertainment can be public or private, involving formal, scripted performance, as in the case of theatre or concerts; or unscripted and spontaneous, as in the case of children's games. Most forms of entertainment have persisted over many centuries, evolving as a result of changes in culture, technology, and fashion. Films and video games, for example, although they use newer media, continue to tell stories, present drama, and play music. Festivals devoted to music, film, or dance allow audiences to be entertained over a number of consecutive days.

Some activities that once were considered entertaining, particularly public punishments, have been removed from the public arena. Other activities, such as fencing or archery, once necessary skills for some, have become serious sports and even professions for the participants, at the same time developing into entertainment with wider appeal for bigger audiences. What is entertainment for one group or individual may be regarded as work by another.

Entertainment often provides fun, enjoyment and laughter. In certain circumstances or contexts, there is an additional serious purpose. This may be the case in the various forms of celebration, religious festival, or satire for example. Hence, there is the possibility that what appears as entertainment may also be a means of achieving insight or intellectual growth. The appeal of entertainment, along with its capacity to cross over different media and its potential for creative remix, has ensured the continuity and longevity of many recognisable forms, themes, images, and structures.

Definitions

Entertainment can be distinguished from other activities such as education and marketing even though they have learned how to use the appeal of entertainment to achieve their different goals. The importance and impact of entertainment is recognised by scholars[1][2] and its increasing sophistication has influenced practices in other fields such as museology.[3][4]

Psychologists say the function of media entertainment is "the attainment of gratification".[5] No other results or measurable benefit are usually expected from it (except perhaps the final score in a sporting entertainment). This is in contrast to education (which is designed with the purpose of developing understanding or helping people to learn) and marketing (which aims to encourage people to purchase commercial products). However, the distinctions become blurred when education seeks to be more "entertaining" and entertainment or marketing seek to be more "educational". Such mixtures are often known by the neologisms "edutainment" or "infotainment". The psychology of entertainment as well as of learning has been applied to all these fields.[6] Some education-entertainment is a serious attempt to combine the best features of the two.[7][8]

An entertainment might go beyond gratification and produce some insight in its audience when it skilfully considers universal philosophical questions such as: "What is the meaning of life?"; "What does it mean to be human?"; "What is the right thing to do?"; or "How do I know what I know?". Questions such as these drive many narratives and dramas, whether they are presented in the form of a story, film, play, poem, book, dance, comic, or game. Dramatic examples include Shakespeare's very influential play Hamlet, whose hero articulates these concerns in poetry; and films, such as The Matrix, which explores the nature of knowledge.[9] Novels give great scope for investigating these themes while they entertain their readers.[10] An example of a creative work that considers philosophical questions so entertainingly that it has been presented in a very wide range of forms, is The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Originally a radio comedy, this story became so popular that it has also appeared as a novel, film, television series, stage show, comic, audiobook, LP record, adventure game and online game and has been translated into many languages.[11] Its themes encompass the meaning of life, as well as "the ethics of entertainment, artificial intelligence, multiple worlds, God, and philosophical method".[12]

History

People probably started entertaining themselves by telling stories around a fire in prehistoric times, and storytelling has been an important part of most forms of entertainment ever since. Stories are still told in this original form, for example while camping or when listening to the stories of another culture as a tourist. Entertainment is provided for mass audiences in purpose-built structures such as a theatre, auditorium, or stadium. One of the most famous venues is the Colosseum where spectacles, competitions, races, and sports were presented as public entertainment.

Relatively minor changes to the form and venue of an entertainment continue to come and go as they are affected by the period, fashion, culture, technology, and economics. For example, a story told in dramatic form might be presented in an open-air theatre, a music hall, a movie theatre, a multiplex, or via a personal electronic device such as a tablet computer. Some forms become controversial and are eventually prohibited. Hunting wild animals is still regarded by some as entertainment but as with other forms of animal entertainment (see below) it has become more controversial. Hunting wild animals, as a form of public entertainment and spectacle, was introduced into the Roman Empire from Carthage.[13]

Some forms of entertainment, especially music and drama, have developed into numerous variations of form to suit a very wide range of personal preferences and cultural expression. Many forms are blended or supported by other forms. For example, drama and stories use music as enhancement. Sport and games are incorporated into other forms to increase appeal. Commonly, entertainment evolves from serious or necessary activities (such as running and jumping) into competition and then into entertainment. Gladiatorial combats, also known as "gladiatorial games", popular during Roman times, provide a good example of an activity that is a combination of sport, punishment, and entertainment. Such examples of violent entertainment have supported arguments that contemporary entertainment is less brutal than it was in the past, in spite of the ubiquity of violence in the more sophisticated technology used by modern media as a medium for entertainment.[14] Many of these once necessary skills, such as perhaps pole vaulting, need equipment, which has become increasingly sophisticated. Other activities, such as walking on stilts, are still seen in circus performances in the 21st century.

Entertainment can change in response to cultural or historical shifts. For example, entertainment evolved into different forms and expressions as a result of World War I,[15][16][17][18] the Great Depression and the Russian revolution.[19] During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Revolutionary opera was sanctioned by the Communist party.

Public punishment

Although most forms of entertainment have evolved and continued over time, some once-popular forms are no longer as acceptable. For example, during earlier centuries in Europe, watching or participating in the punishment of criminals or social outcasts was an accepted and popular form of entertainment. Many forms of public humiliation also offered local entertainment in the past. Even capital punishment such as hanging and beheading, offered to the public as a warning, were also regarded partly as entertainment. Capital punishments that lasted longer, such as stoning and drawing and quartering, afforded a greater public spectacle. "A hanging was a carnival that diverted not merely the unemployed but the unemployable. Good bourgeois or curious aristocrats who could afford it watched it from a carriage or rented a room."[20] Public punishment as entertainment lasted until the 19th century by which time "the awesome event of a public hanging aroused the[ir] loathing of writers and philosophers".[20] Both Dickens and Thackeray wrote about a hanging in Newgate Prison in 1840, and "taught an even wider public that executions are obscene entertainments".[20]

Children

Children's entertainment is centred on play and is significant for their growth and learning. Entertainment is also provided to children or taught to them by adults and many activities that appeal to them such as puppets, clowns, pantomimes and cartoons are also enjoyed by adults.[21][22]

Children have always played games. It is accepted that as well as being entertaining, playing games helps children's development. One of the most famous visual accounts of children's games is a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder called Children's Games, painted in 1560. It depicts children playing a range of games which were presumably typical of the time. Many of these games, such as marbles, hide-and-seek, blowing soap bubbles and piggyback riding continue to be played.

Most forms of entertainment can be or are modified to suit children's needs and interests. During the 20th century, it became understood that the psychological development of children occurs in stages and that their capacities differ from adults. Hence, stories and activities, whether in books, film, or video games were developed specifically for child audiences. Countries have responded to the special needs of children and the rise of digital entertainment by developing systems such as television content rating systems, to guide the public and the entertainment industry.

In the 21st century, as with adult products, much entertainment is available for children on the internet for private use. This constitutes a significant change from earlier times. The amount of time expended by children indoors on screen-based entertainment and the "remarkable collapse of children's engagement with nature" has drawn criticism for its negative effects on imagination, adult cognition and psychological well-being.[23][24][25]

Forms

Music

Music is a supporting component of many kinds of entertainment and most kinds of performance. For example, it is used to enhance storytelling, it is indispensable in dance (1) and opera, and is usually incorporated into dramatic film or theatre productions.[26]

Music is also a universal and popular type of entertainment on its own, constituting an entire performance such as when concerts are given (2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 ). Depending on the rhythm, instrument, performance and style, music is divided into many different genres, such as classical, jazz or folk (3, 5, 8), and rock (6, 9). Since the 20th century, performed music, once available only to those who could pay for the performers, has been available cheaply to individuals by the entertainment industry which broadcasts it or pre-records it for sale.

The wide variety of musical performances, whether or not they are artificially amplified (4, 6, 7, 9, 10), all provide entertainment irrespective of whether the performance is from soloists (4, 6), choral (2) or orchestral groups (5, 8), or ensemble (3). Live performances use specialised venues, which might be small or large; indoors or outdoors; free or expensive. The audiences have different expectations of the performers as well as of their own role in the performance. For example, some audiences expect to listen silently and are entertained by the excellence of the music, its rendition or its interpretation (5, 8). Other audiences of live performances are entertained by the ambience and the chance to participate (7, 9). Even more listeners are entertained by packaged music and listen privately (10).

The instruments used in musical entertainment are either solely the human voice (2, 6) or solely instrumental (1, 3) or some combination of the two (4, 5, 7, 8). Whether the performance is given by vocalists or instrumentalists, the performers may be soloists or part of a small or large group, in turn entertaining an audience that might be individual (10), passing by (3), small (1, 2) or large (6, 7, 8, 9). Singing is generally accompanied by instruments although some forms, notably a cappella and overtone singing, are unaccompanied.

-

1 Traditional instruments used to accompany dance (Tibet, 1949)

-

2 Children's choir providing musical entertainment (Russia, 1979)

-

3 Ensemble entertains travellers in the Paris Métro (2002)

-

4 Soloist enhanced by instrumental support and lighting (Russia, 2007)

-

5 Choir and orchestra in ecclesiastical setting (Italy, 2008)

-

6 Contemporary audience in ancient outdoor stadium (Greece, 2009)

-

7 Musical concert with standing audience (Germany, 2008)

-

8 Concert hall audience (Netherlands, 2010)

-

9 Crowd surfing at a concert (France, 2011)

-

10 Woman listening privately to music through headphones (Russia, 2010)

Games

Games are played for entertainment - sometimes purely for entertainment, sometimes for achievement or reward as well. They can be played alone, in teams, or online; by amateurs or by professionals. The players may have an audience of non-players, such as when people are entertained by watching a chess championship. On the other hand, players in a game may constitute their own audience as they take their turn to play. Often, part of the entertainment for children playing a game is deciding who will be part of their audience and who will be a player.

Equipment varies with the game. Board games, Go, Monopoly or backgammon need a board and markers. Card games, such as whist, poker and Bridge have long been played as evening entertainment among friends. For these games, all that is needed is a deck of playing cards. Other games, such as bingo, played with numerous strangers, have been organised to involve the participation of non-players via gambling. Many are geared for children, and can be played outdoors, including hopscotch, hide and seek, or Blind man's bluff. The list of ball games is quite extensive. It includes, for example, croquet, lawn bowling and paintball as well as many sports using various forms of ball. The options cater to a wide range of skill and fitness levels. Physical games can develop agility and competence in motor skills. Number games such as Sudoku and puzzle games like the Rubik's cube can develop mental prowess.

Video games, played using a controller to create results on a screen, can also be played online with participants joining in remotely. In the second half of the 20th century and in the 21st century the number of such games increased enormously, providing a wide variety of entertainment to players around the world.[27][28] They are particularly popular in Korea.[29]

Literature

Literature contains many genres designed, in whole or in part, as entertainment. Comics and cartoons, for example, are literary types that use drawings, usually in combination with text, to convey an entertaining narrative.[30] Comics often have elements of fantasy. Some comics are produced by companies that are part of the entertainment industry. Others have unique authors who offer a more personal, philosophical view of the world and the problems people face. Comics about superheroes such as Superman are of the first type.[31] Examples of the second sort include the individual work over 50 years of Charles M. Schultz who produced a popular comic called Peanuts about the relationships among a cast of child characters;[32] and Michael Leunig who entertains by producing whimsical cartoons that also incorporate social criticism. The Japanese Manga style differs from the western approach in that it encompasses a wide range of genres and themes for a readership of all ages. Caricature uses a kind of graphic entertainment for purposes ranging from merely putting a smile on the viewer's face, to raising social awareness, to highlighting the moral characteristics of a person being caricatured.

Limericks use verse in a strict, predictable rhyme and rhythm to create humour and to amuse an audience of listeners. Interactive books such as "choose your own adventure" can make literary entertainment more participatory.

Comedy

Comedy is both a genre of entertainment and a component of it, providing laughter and amusement, whether the comedy is the sole purpose or used as a form of contrast in an otherwise serious piece. It is a valued contributor to many forms of entertainment, including in literature, theatre, opera, film and games.[33][34] In medieval times, all comic types - the buffoon, jester, hunchback, dwarf, jokester, were all "considered to be essentially of one comic type: the fool", who while not necessarily funny, represented "the shortcomings of the individual".[35][36]

Shakespeare wrote seventeen comedies which use many of the techniques still called upon by performers and writers of comedy, such as jokes, puns, parody, wit, observational humor or the unexpected effect of irony.[37][38] One-liner jokes and satire are also used to comedic effect in literature. In farce, the comedy is a primary purpose.

The meaning of the word "comedy" and the audience's expectations of it, have changed over time and vary according to culture.[39] Simple physical comedy such as slapstick, is entertaining to a broad range of people of all ages. However, as cultures become more sophisticated, national nuances appear in the style and references so that what is amusing in one country may be unintelligible in another.[40]

Performance

Live performances before an audience constitute a major form of entertainment, especially before the invention of audio and video recording. Performance takes a wide range of forms, including theatre, music and drama. Opera is an example of a performance style that encompass all three forms, demanding a high level of musical and dramatic skill, collaboration and production expertise as well.

Storytelling

Storytelling is an ancient form of entertainment that has influenced almost all other forms. It may be delivered directly to a small listening audience or it may be a component of any piece that relies on a narrative, such as film, drama, ballet, and opera. Stories remain a common way of entertaining a group that is on a journey. Chaucer's stories in his literary work The Canterbury Tales are an example of how stories were used to pass the time and entertain an audience of travellers or pilgrims. Even though journeys can now be completed much faster, stories are still told to passengers en route in cars and aeroplanes either orally or delivered by some form of technology.

The power of stories to entertain is evident in one of the most famous ones—Scheherazade—a story in the Persian professional storytelling tradition, of a woman who saves her own life by telling stories.[41][42][43] The connections between the different types of entertainment are shown by the way that stories like this inspire a retelling in another medium, such as music or games. For example, composers Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Maurice Ravel and Karol Szymanowski have all been inspired by the Scheherazade story and turned it into an orchestral work. The Magic of Scheherazade is an innovative video game based on the tale. Stories may be told wordlessly, in music, dance or puppetry for example, such as in the Javanese tradition of wayang, in which the performance is accompanied by a gamelan orchestra or the similarly traditional Punch and Judy show.

Epic poems, such as Homer's Odyssey and Iliad tell such gripping stories that they have inspired countless other stories in all forms of entertainment. Collections of stories, such as Grimms' Fairy Tales, have been similarly influential. This collection of folk stories was originally published in the early 19th century, became iconic and had significant influence in modern pop culture which subsequently used its themes, images, symbols and structural elements to create new forms of entertainment.[44]

Some of the most powerful and long-lasting stories are the foundation stories, also called origin or creation myths such as the Dreamtime myths of the Australian aborigines, the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh,[45] or the Hawaiian stories of the origin of the world.[46] These too are developed into books, films, music and games in a way that increases their longevity and enhances their entertainment value.

Theatre

Theatre performances, typically dramatic or musical, are presented on a stage for an audience, whose expectations about the performance and their engagement with it have changed over time (1).[47] Vaudeville and music halls, for example, were once popular forms of theatrical entertainment popular in the United States, England, Canada, Australia and New Zealand before being superseded.[48] Radio and television, often broadcast live, is a 20th century version of theatre entertainment that exists alongside the traditional forms.[49] Plays, musicals, monologues, pantomimes, and performance poetry are examples from the very long history of theatrical entertainment and performance art.[50][51][52] Stand-up comedy is a type of performance usually given in a theatre.[53]

The stage and the spaces set out in front of it for an audience create a theatre. All types of stage are used with all types of seating for the audience, including the impromptu or improvised (2, 3, 6); the temporary (2); the elaborate (9); or the traditional and permanent (5, 7). They are erected indoors (3, 5, 9) or outdoors (2, 4, 6). The skill of managing, organising and preparing the stage for a performance is known as stagecraft (10). The audience's experience of the entertainment is affected by their expectations and the stagecraft as well as by the type of stage and the type and standard of seating provided.

-

1 Satirical representation of audience reaction (1809)

-

2 Improvised stage for a public performance at a fair (1642)

-

3 Improvised stage for domestic theatre

-

4 Outdoor stage before a show

-

5 Concert theatre ready for solo instrumentalist

-

6 Outdoor theatre created from Edinburgh castle forecourt

-

7 Traditional stage for Japanese Noh theatre

-

8 Stage for theatre in the round

-

9 Teatro Colón, a highly decorative, horseshoe theatre

-

10 Stagecraft - a locking rail backstage

Cinema and film

Films are a major form of entertainment. Some are intended as a form of escapism, while others are more layered and require a deeper engagement or more thoughtful response from their audience. Increasingly sophisticated techniques have been used in the film medium to delight and entertain audiences. Animation, which involves the display of rapid movement in an art work, is one of these techniques that particularly appeals to younger audiences.[54] Not all films have entertainment as their primary purpose: documentary film aims to create a record or inform its audience.[55] Films also re-imagine entertainment from other forms, turning stories, books and plays, for example, into new entertainments.[56]

Dance

The many forms of dance provide entertainment for all age groups and cultures. It can be serious in tone, such as when it is used to express a culture's history or important stories; it may be provocative; or it may put in the service of comedy.[57] Since it combines many forms of entertainment - music, movement, storytelling, theatre - it provides a good example of the various ways that these forms can be combined to create entertainment for different purposes and audiences.

Dances can be performed solo (1, 4); in pairs, (2, 3); in groups, (5, 6, 7); or massed performers, (8). They might be improvised (4) or highly choreographed (1, 2, 5, 10); spontaneous for personal entertainment, (such as when children begin dancing for themselves); a private audience, (4); a paying audience (2); a world audience (10); or an audience interested in a particular dance genre (3, 5). They might be a part of a celebration, such as a wedding or New Year (6, 8); a cultural ritual with a specific purpose, such as a dance by warriors like a haka or (7). Some dances, such as traditional dance in 1 and ballet in 2, need a very high level of skill and training; others, such as the can-can, require a very high level of energy and physical fitness. Entertaining the audience is a normal part of dance but its physicality often also produces joy for the dancers themselves. (9).

Some dances, such as the quadrille, once popular at social gatherings like balls, are now rarely performed.[58] On the other hand, many dances, including folk dances (such as Scottish Highland dancing and Irish dancing), have evolved into competitions, which by adding to their audiences, has increased their entertainment value.

-

1 Traditional dancer (Thailand)

-

2 Harlequin and Columbine (Denmark)

-

3 Ballroom dancing (Czech Republic)

-

4 Belly dancer (Morocco)

-

5 Morris dancing (England)

-

6 Highland wedding (Scotland, 1780)

-

7 Warrior dancers (Papua New Guinea)

-

8 Fire Dragon dance for Chinese New Year

-

10 Children in Mass Games (North Korea)

Animals

Animals have been used for the purposes of entertainment for millennia. For example, animals kept in zoos in ancient times were often kept there for later use in the arena as entertainment or for their entertainment value as exotica.[59] However, the use of animals for entertainment is often controversial. They have been hunted for entertainment (as opposed to hunted for food); displayed while they hunt for prey; watched when they compete with each other; and watched while they perform a trained routine for human amusement.

Many contests between animals are now regarded as sports - for example, horse racing is regarded as both a sport and an important source of entertainment. In Australia, the horse race run on Melbourne Cup Day is a public holiday and the public regards the race as an important annual event. Like horse racing, camel racing requires human riders, while greyhound racing does not. People find it very entertaining to watch trained horses, camels or dogs race competitively.

Other contests between animals, once popular entertainment for the public, have become illegal because of the cruelty involved. Among these are blood sports such as bear-baiting, dog fighting and cockfighting. Some contests involving animals have both supporters and detractors and so are more controversial than ones already prohibited. Fox hunting, which involves the use of horses as well as hounds, and bullfighting, which has a strong theatrical component, are two of these. Both have a long and significant cultural history.

Animals that perform trained routines or "acts" for human entertainment include fleas in flea circuses, dolphins in dolphinaria, and monkeys doing tricks for an audience on behalf of the player of a street organ.

Circus

A circus is a special form of theatrical performance that involves acrobatics and often performing animals. Philip Astley is regarded as the founder of the modern circus in the second half of the 18th century and Jules Léotard is the French performer credited with developing the art of the trapeze, considered synonymous with circuses.[60] Circuses are usually thought of as a travelling show, but permanent venues have also been used.[61]

Magic

Magic, often called stage magic or conjuring, is a form of performance entertainment that relies on deception, psychological manipulation, sleight of hand and other forms of trickery to give an audience the illusion that they a performer can achieve the impossible. Magic is done in a variety of media and locations: on stage, on television, in the street, and live at parties or events. Showmanship is often an essential part of magic performing, and magic is often combined with other forms of entertainment, such as comedy or music.

Street performance

Street performance or "busking" is a form of performance that has been meeting the public's need for entertainment for centuries.[62] Some historical European performers were called minstrels or troubadours. The art and practice of busking is still celebrated at annual busking festivals.[63]

There are three basic forms of street performance:

- "Circle shows" are shows that tend to gather a crowd around them. Usually they have a distinct beginning and end and are done in conjunction with street theatre, puppeteering, magicians, comedians, acrobats, jugglers and sometimes musicians. Circle shows have the potential to be the most lucrative for the performer because there are likely to be more donations from larger audiences if they are entertained by the act. Good buskers control the crowd so patrons do not obstruct foot traffic.

- "Walk-by acts" have no distinct beginning or end. Typically have the busker provides an entertaining ambience, often with an unusual instrument, and the audience may not stop to watch or form a crowd. Sometimes a walk-by act will spontaneously turn into a circle show.

- "Café busking" is done mostly in restaurants, pubs, bars and cafés, although this type has used public transport as a venue.

Parades

Parades are held for a range of purposes, often more than one. Their mood may be sombre, in which case they are often called a procession, or they may be festive. Being public events that are designed to attract attention as well as activities that necessarily divert normal traffic, they have a clear entertainment value to their audiences. Some of the audience may have made a special effort to attend while others become part of the audience by happenstance. Whatever their mood or primary purpose, parades attract and entertain people who watch them pass by. Occasionally, a parade takes place in an improvised theatre space (such as the Trooping the Colour in 5) and tickets are sold to the physical audience while the global audience participates via broadcast.

One of the earliest forms of parade were "triumphs" - grand and sensational displays of foreign treasures and spoils, given by triumphant Roman generals to celebrate their victories. They presented conquered peoples and nations that exalted the prestige of the victor. "In the summer of 46 B.C.E. Julius Caesar chose to celebrate four triumphs held on different days extending for about one month."[64] In Europe from the Middle Ages to the Baroque the Royal Entry celebrated the formal visit of the monarch to the city with a parade through elaborately decorated streets, passing various shows and displays. The annual Lord Mayor's Show in London is one example of a civic parade that has survived since medieval times.

Parades generally impress and delight (2, 3, 6, 8), often by including unusual, colourful costumes (2, 3, 6). Sometimes they also commemorate (5) or celebrate (1, 6, 7, 8). Sometimes they have a serious purpose, such as when the context is military or religious (5, 7) and the audience might engage with the activity in a less demonstrable way or have a role to play. (1, 4, 5, 7). Even if a parade uses new technology and is some distance away (7), it is likely to have a strong appeal, draw the attention of onlookers and entertain them.

-

1 Triumph of Caesar, Andreani (1588/9)

-

2 Festive parade in Brazil (2004)

-

3 Costumes in West Indian Day parade (2008)

-

4 Parade from the onlooker perspective (1816)

-

5 Respectful crowd in Canada (1945)

-

6 Celebratory parade in London before seated audience (2008)

-

7 Ganesh Visarjan, Mumbai (2007)

-

8 Flypast (2012)

Fireworks

Fireworks are a part of many public entertainments and have retained an enduring popularity since they became a "crowning feature of elaborate celebrations" in the 17th century. First used in China, classical antiquity and Europe for military purposes, fireworks were most popular in the 18th century and high prices were paid for pyrotechnists, especially the skilled Italian ones, who were summoned to other countries to organise displays.[65][66] Fire and water were important aspects of court spectacles because the displays "inspired by means of fire, sudden noise, smoke and general magnificence the sentiments thought fitting for the subject to entertain of his sovereign: awe fear and a vicarious sense of glory in his might. Birthdays, name-days, weddings and anniversaries provided the occasion for celebration."[67] One of the most famous courtly uses of fireworks was one used to celebrate the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and while the fireworks themselves caused a fire,[68] the accompanying Music for the Royal Fireworks written by George Frideric Handel has been popular ever since. Aside from their contribution to entertainments related to military successes, courtly displays and personal celebrations, fireworks are also used as part of religious ceremony. For example, during the Indian Dashavatara Kala of Gomantaka "the temple deity is taken around in a procession with a lot of singing, dancing and display of fireworks".[69]

The "fire, sudden noise and smoke" of fireworks is still a significant part of public celebration and entertainment. For example, fireworks were one of the primary forms of display chosen to celebrate the turn of the millennium around the world. As the clock struck midnight and 1999 became 2000, firework displays and open-air parties greeted the New Year as the time zones changed over to the next century. Fireworks, carefully planned and choreographed, were let off against the backdrop of many of the world's most famous buildings, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt, the Acropolis in Athens, Red Square in Moscow, Vatican City in Rome, the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, and Elizabeth Tower in London.

Sport

Sporting competitions have always provided entertainment for crowds. To distinguish the players from the audience, the latter are often known as spectators. Developments in stadium and auditorium design, as well as in recording and broadcast technology, have allowed off-site spectators to watch sport, with the result that the size of the audience has grown ever larger and spectator sport has become increasingly popular. Two of the most popular sports with global appeal are association football and cricket. Their ultimate international competitions, the World Cup and test cricket, are broadcast around the world. Beyond the very large numbers involved in playing these sports, they are notable for being a major source of entertainment for many millions of non-players worldwide.[70] A comparable multi-stage, long-form sport with global appeal is the Tour de France, unusual in that it takes place outside of special stadia, being run instead in the countryside.[71]

Aside from sports that have world-wide appeal and competitions, such as the Olympic Games, the entertainment value of a sport depends on the culture and country in which it is played. For example, in the United States, baseball and basketball games are popular forms of entertainment; in Bhutan, the national sport is archery; in Iran, it is freestyle wrestling. Japan's unique sumo wrestling contains ritual elements that derive from its long history.[72]

The evolution of an activity into a sport and then an entertainment is also affected by the local climate and conditions. For example, the modern sport of surfing is associated with Hawaii and that of snow skiing probably evolved in Scandinavia. While these sports and the entertainment they offer to spectators have spread around the world, people in the two originating countries remain well known for their prowess. Sometimes the climate offers a chance to adapt another sport such as in the case of ice hockey which is an important entertainment in Canada.

Fairs, expositions, shopping

Fairs and exhibitions have existed since ancient and medieval times, displaying wealth, innovations and objects for trade and offering specific entertainments as well as being places of entertainment in themselves.[73] Whether in a medieval market or a small shop, "shopping always offered forms of exhilaration that took one away from the everyday".[74] However, in the modern world, "merchandising has become entertainment: spinning signs, flashing signs, thumping music ... video screens, interactive computer kiosks, day care .. cafés".[74]

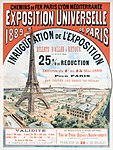

By the 19th century, "expos" which encourage arts, manufactures and commerce had become truly international and hugely popular and were having an enormous impact. From London 1851 to Paris 1900, for example, "in excess of 200 million visitors had entered the turnstiles in London, Paris, Vienna, Philadelphia, Chicago[75] and a myriad of smaller shows around the world."[73] Since World War II "well over 500 million visits have been recorded through world expo turnstiles"[76] As a form of spectacle and entertainment, expositions influenced "everything from architecture, to patterns of globalisation, to fundamental matters of human identity"[76] and in the process established the close relationship between "fairs, the rise of department stores and art museums",[77] the modern world of mass consumption and the entertainment industry.

-

Advertisement for 1889 Paris Universal Exposition

-

Audience queueing for Qatar's World Exposition Pavilion in Shangahai (2010)

-

Ball pit of the type provided for children's entertainment in shopping malls

Industry

Although kings, rulers and powerful people have always been able to pay for entertainment to be provided for them and in many cases have paid for public entertainment, people generally have made their own entertainment or when possible, attended a live performance. Technological developments in the 20th century meant that entertainment could be produced independently of the audience, packaged and sold on a commercial basis by an entertainment industry.[78][79] Sometimes referred to as show business, the industry relies on business models to produce, market, broadcast or otherwise distribute many of its traditional forms, including performances of all types.[80] The industry became so sophisticated that its economics became a separate area of academic study.[81]

The film industry is one part of the entertainment industry. Components of it include the Hollywood and Bollywood film industries, as well as the cinema of the United Kingdom and all the cinemas of Europe, including France, Germany, Spain, Italy and others.[82] The sex industry is another component of the entertainment industry, applying the same forms and media (for example, film, books, performances) to the development, marketing and sale of sex products on a commercial basis.

Amusement parks entertain paying guests with rides such as roller coasters, train rides, water rides, and dark rides, as well as other events and associated attractions. The parks are built on a large area subdivided into themed areas named "lands". The buildings in amusement parks are specially created to represent the theme and are not usually authentic or completely functional. Sometimes the whole amusement park is based on one theme, such as the various SeaWorld parks that focus on the theme of sea life.

One of the consequences of the development of the entertainment industry has been the creation of new types of employment. While jobs such as writer, musician and composer exist as they always have, people doing this work are likely to be employed by a company rather than a patron as it once would have been. New jobs have appeared, such as gaffer or special effects supervisor in the film industry, and attendants in an amusement park.

Prestigious awards are given by the industry for excellence in the various types of entertainment. For example, there are awards for Music, Games, Comics, Comedy, Theatre, Television, Film, Video Gaming, Dance and Magic. Sporting awards are made for the results and skill, rather than for the entertainment value.

-

Film reels - packaged entertainment

-

Choosing music from a record store (Germany, 1988)

-

Sleeping Beauty Castle in Disneyland amusement park

Architecture for entertainment venues

Purpose-built structures for offering entertainment and accommodating audiences have produced many famous and innovative buildings.[83] Modern theatre structures are among the most recognisable but specific architecture for entertainment was built during ancient times. The ancient Greeks built open air theatres and the Romans developed the stadium in an oval form known as a circus. Some of the grandest modern buildings for entertainment have brought fame to their cities as well as their designers. For example, the Sydney Opera House is a World Heritage Site. The O₂ is an entire entertainment precinct in London that contains an indoor arena, a music club, a cinema and exhibition space. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus in Germany is a theatre designed and built for performances of one specific musical composition.

Two of the chief architectural concerns for the design of venues for mass audiences are speed of egress and safety. The speed at which the venue can be emptied is important both for amenity and safety because large crowds take a very long time to disperse from a badly designed venue and this in turn creates a safety risk. The Hillsborough disaster is an example of how poor aspects of building design can contribute to audience deaths. Sightlines and acoustics are also important design considerations in most theatrical venues.

-

The Grand Foyer in the Palais Garnier, Paris, influenced architecture around the world

-

Maracanã Rio de Janeiro, at inauguration the world's largest stadium by capacity

-

The O₂ entertainment precinct from the air, London

Electronic media

By the second half of the 20th century, electronic media was capable of delivering stories, theatre, music and dance to mass audiences. In the 1940s, radio was the electronic medium for family entertainment and information.[84][85][86] In the 1950s, it was television that was the new medium and it rapidly became global, bringing visual entertainment, first in black and white, then in colour, to the world.[87] By the 1970s games could be played electronically, then hand-held devices provided mobile entertainment, and by the last decade of the 20th century, via networked play. In combination with products from the entertainment industry, all the traditional forms of entertainment became available personally. People could not only select an entertainment product such as a piece of music, film or game, they could choose the time and place to use it. The "proliferation of portable media players and the emphasis on the computer as a site for film consumption" together have significantly changed how audiences encounter films.[88]

The rapid development of technology for entertainment was assisted by improvements in data storage devices such as cassette tapes or compact discs, along with increasing miniaturisation. By the second decade of the 21st century, analogue recording was being replaced by digital recording and all forms of electronic entertainment began to converge.[89] Media convergence is said to be more than technological: the convergence is cultural as well.[2] It is also "the result of a deliberate effort to protect the interests of business entities, policy institutions and other groups"[88]

One of the most notable consequences of the rise of electronic entertainment has been the rapid obsolescence of the various recording and storage methods. As an example of speed of change driven by electronic media, it is notable that over the course of one generation, television as a medium for receiving standardised entertainment products went from unknown, to novel, to ubiquitous and finally to superseded.[90] One estimate was that by 2011 over 30 percent of households in the US, would own a Wii console, "about the same percentage that owned a television in 1953".[91] It is expected that halfway through the second decade of the 21st century, television will be completely replaced by online. The so-called "digital revolution" has resulted in an increasingly transnational marketplace that has caused difficulties for governments, business, industries and individuals as they all try to keep up.[92][93][94][95] Other flow on effects of the shift are likely to include those on public architecture such as hospitals and nursing homes, where television, regarded as an essential entertainment service for patients and residents, will need to be replaced by access to the internet.

Just as the introduction of television altered the availability, cost, variety and quality of entertainment products for the public, so will the convergence of online entertainment. Also notable is that while technology offers increased speed of delivery and increases demand for entertainment products, in themselves the forms that make up the content are relatively stable.

See also

- Entertainment during the Great Depression

- Entertainment in the 16th century

- Entertainment law

- History of film

- Leisure

- List of basic entertainment topics

- List of entertainment industry topics

- Mass media

- Performance art

- Radio

References

- ^ For example, the application of psychological models and theories to entertainment is discussed in Part III of Bryant, Jennings (2006). Psychology of Entertainment. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. pp. 367–434. ISBN 0-8058-5238-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sayre, Shay (2010). Entertainment and Society: Influences, Impacts, and Innovations (Google eBook) (2nd ed.). Oxon, New York: Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 0-415-99806-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Sayre" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Frost, Warwick (ed), ed. (2011). Conservation, Education, Entertainment?. Channel View Publication. ISBN 978-1-84541-164-0.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Knell, Simon J., ed. (2007). Museum Revolutions. Oxon, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-93264-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Zillmann, Dolf (2000). Media Entertainment - the psychology of its appeal. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.Taylor & Francis e-library (2009). pp. vii. ISBN 0-8058-3324-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ For example, marketers mix commercial messages with non-commercial messages in entertainments on radio, television, films, videos and games. Shrum, L. J. J. (2012). The Psychology of Entertainment Media (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-84872-944-5.

- ^ Arvind Singhal, Michael J. Cody, Everett Rogers, Miguel Sabido, ed. (2008). Entertainment-Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-4106-0959-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ de Freitas, Sara, ed. (2011). Digital Games and Learning. London, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4411-9870-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Irwin, William (ed) (2002). The Matrix and Philosophy. Peru, Illinois: Carus Publishing Company. p. 196. ISBN 0-8126-9502-X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Jones, Peter (1975). Philosophy and the Novel. Oxford, Clarendon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Simpson, M. J. (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (Second Edition ed.). Pocket Essentials. p. 120. ISBN 1-904048-46-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Joll, Nicholas (ed) (2012). Philosophy and The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230291126.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Potter, David Stone (1999). Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. University of Michigan Press. p. 308. ISBN 0-472-10924-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schechter, Harold (2005). Savage Pastimes: A Cultural History Of Violent Entertainment. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0312282761.

- ^ Roshwald, Aviel (2002). European Culture in the Great War: The Arts, Entertainment and Propaganda, 1914-1918. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57015-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Heinrich, Anselm (2007). Tony Meech (ed.). Heinrich, Entertainment, propaganda, education: regional theatre in Germany and Britain between 1918 and 1945. Hatfield [England]: University of Hertfordshire Press,. ISBN 978-1-902-80674-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Arthur, Max (2001). When this bloody war is over: soldiers' songs from the First World War. London: Piatkus. ISBN 0749922524.

- ^ Horn, David, ed. (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World Part 1 Media, Industry, Society. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-6321-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McReynolds, Louise (2003). Russia at Play: Leisure Activities at the End of the Tsarist Era. Cornell University. ISBN 10987654321.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b c Gay, Peter (2002). Schnitzler's Century - The making of middle-class culture 1815-1914. New York, London: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 121. ISBN 0-393-32363-3.

- ^ O'Brien, John (2004). Harlequin Britain: Pantomime and Entertainment, 1690–1760. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7910-8.

- ^ Geipel, John (1972). The cartoon: a short history of graphic comedy and satire. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0715353284.

- ^ Cobb, Edith (1977). The ecology of imagination in childhood. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231038704.

- ^ Louv, Richard (c2005). Last Child in the Woods: saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 1565123913.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Monbiot, George (19 November 2012). "If children lose contact with nature they won't fight for it". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (2006). A concise history of western music. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521842945.

- ^ Rutter, Jason, ed. (2006). Understanding Digital Games,. London, California, New Delhi: Sage Publications. ISBN 1-4129-0033-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Newman, James (2004). Videogames. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-64290-2.

- ^ Jin, Dal Yong (2010). Korea's Online Gaming Empire. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0-262-01476-2.

- ^ Chapman, James (2011). British comics: a cultural history. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861898555.

- ^ Benton, Mike (c1992). Superhero comics of the Golden Age: the illustrated history. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing. ISBN 087833808X.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ The philosophical and theological implications of Schultz's work were explored in: Short, Robert L. (1965/1999). The Gospel According to Peanuts. Westminster: John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22222-6.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Roston, Murray (2011). The comic mode in English literature: from the Middle Ages to today. London: Continuum. ISBN 9781441195883.

- ^ Grindon, Leger (2011). The Hollywood romantic comedy: conventions, history, controversies. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405182669.

- ^ Hokenson, Jan Walsh (2006). The Idea of Comedy: History, Theory, Critique. Cranbury, NJ: Rosemont Publishing and Printing Corp. pp. 150–1. ISBN 0-8386-4096-6.

- ^ Hornback, Robert (2009). The English clown tradition from the middle ages to Shakespeare. Woodbridge Suffolk, Rochester, NY:: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 9781843842002.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Gay, Penny (2008). The Cambridge introduction to Shakespeare's comedies. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521856683.

- ^ Ellis, David (c2007). Shakespeare's practical jokes: an introduction to the comic in his work. Lewisburg [Pa.]: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 0838756808.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Thorpe, Ashley (c2007). The role of the chou ("clown") in traditional Chinese drama: comedy, criticism, and cosmology on the Chinese stage. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0773453032.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Charney, Maurice, ed. (2005). Comedy: A Geographic and Historical Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32706-8 (set).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Yamanaka, Yuriko (2006). The Arabian nights and orientalism: perspectives from East & West. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Burton, Sir Richard (1821-1890)(in English) (1958). Arabian nights. A plain and literal translation of the Arabian nights' entertainments: now entitled The book of the thousand and one nights. London: Barker.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Caracciolo, Peter L., ed. (1988). The Arabian nights in English literature : studies in the reception of The thousand and one nights into British culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan. ISBN 033336693X.

- ^ Rankin, Walter (2007). Grimm pictures: fairy tale archetypes in eight horror and suspense films. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Co. ISBN 9780786431748.

- ^ The epic of Gilgamesh: the Babylonian epic poem and other texts in Akkadian and Sumerian (English - translated from Akkadian and Sumerian by Andrew George). London: Allen Lane. 1999. ISBN 0713991968.

- ^ Thompson, Vivian Laubach (1966). Hawaiian Myths of Earth, Sea, and Sky. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1171-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kenrick, John (c2008). Musical theatre: a history. London: Continuum. ISBN 0826428606.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Bailey, Peter (1998). Popular Culture and Performance in the Victorian City. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57417X.

- ^ Stempel, Larry (c2010). Showtime: a history of the Broadway musical theater. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 9780393067156.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ McDonald, Marianne and J. Michael Walton., ed. (2007). The Cambridge companion to Greek and Roman theatre. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521834562.

- ^ Milling, Jane, Joseph W. Donohue, Peter Thomson, ed. (2005). The Cambridge History of British Theatre. Cambridge University Press (3 volumes). ISBN 0521827906.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Mordden, Ethan (2007). All that glittered: the golden age of drama on Broadway. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312338988.

- ^ Robinson, Peter M. (c2010). The dance of the comedians: the people, the president, and the performance of political standup comedy in America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9781558497337.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Cavalier, Stephen (c2011). The world history of animation. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520261127.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Wyver, John (1989). The Moving Image: An International History of Film, Television, and Video. John Wiley & Sons, Limited. ISBN 0631168214.

- ^ Rothwell, Kenneth S. (1999). A History of Shakespeare on Screen: A Century of Film and Television. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521594049.

- ^ Dils, Ann, ed. (2001). Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6412-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fullerton, Susannah (2012). A Dance With Jane Austen: How a Novelist and Her Characters Went to the Ball. Pgw. ISBN 0711232458.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hancocks, David (c2001). A different nature: the paradoxical world of zoos and their uncertain future. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23676-9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Diamond, Michael (2003). Victorian sensation, or, The spectacular, the shocking, and the scandalous in nineteenth-century Britain. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 1843310767.

- ^ Stoddart, Helen (2000). Rings of Desire: Circus History and representation. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5233-5.

- ^ Cohen, David (c. 1981). The buskers: a history of street entertainment. Newton Abbot; North Pomfret, Vt.: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8126-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ For example 2012 Coffs Harbour International Buskers and Comedy Festival

- ^ Gurval, Robert Alan (1995). Actium and Augustus: The Politics and Emotions of Civil War. University of Michigan. p. 20. ISBN 0-472-10590-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Giacomo Casanova, Giacomo Chevalier de Seingalt (1997). History of My Life, Volumes 9-10 Vol 10 (in English translation, Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, and 1970). Baltimore, Maryland; London: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 333. ISBN 0-8018-5666-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Kelly, Jack (2005). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books. ISBN 0465037224.

- ^ Sagarra, Eda (2003). A Social History of Germany 1648-1914. Transaction Publishers. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7658-0982-7.

- ^ Hogwood, Christopher (2005). Handel: Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-521-83636-4.

- ^ Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1992). History of Indian Theatre (vol.2). New Delhi: Shakti Malik Abhinav Publications. p. 286. ISBN 81-7017-278-0.

- ^ Mullin, Bernard James, ed. (2007). Sport Marketing. Human Kinetics. ISBN 978-0-7360-6052-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Thompson, Christopher S. (2008). The Tour de France: A Cultural History. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25630-9.

- ^ Kubota, Makoto (1999). Sumo. Chronicle Books Llc. ISBN 0811825485.

- ^ a b Wilson, Robert (2007). Great Exhibitions: The World Fairs 1851-1937. National Gallery of Victoria. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780724102846.

- ^ a b Moss, Mark Howard (2007). Shopping As an Entertainment Experience. Lanham MD, Plymouth UK: Lexington Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7391-1680-7.

- ^ "World's Colombian Exposition of 1893". Chicago Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b T. J. Boisseau, ed. (2010). Gendering the Fair: Histories of Women and Gender at World's Fairs. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois. p. viii. ISBN 978-0-252-03558-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rydell, Robert W. (1993). World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press. p. 15. ISBN 0226732363.

- ^ Stein, Andi (2009). An Introduction to the Entertainment Industry. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4331-0341-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ben Walmsley (ed.). Key issues in the arts and entertainment industry. Woodeaton, Oxford: Goodfellow Pub. Ltd. ISBN 190688420X.

- ^ Sickels, Robert C. The Business of Entertainment. Greenwood Publishing (Three Volumes).

- ^ Vogel, Harold L (2007). Entertainment industry economics: a guide for financial analysis (7th ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521874858.

- ^ Casper, Drew (2007). Postwar Hollywood, 1946-1962. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 9781405150743.

- ^ Newhouse, Victoria (c2012.). Site and sound: the architecture and acoustics of new opera houses and concert halls. New York: Monacelli Press. ISBN 9781580932813.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Garratt, G.R.M. (c1994). The early history of radio: from Faraday to Marconi. London, UK: Institution of Electrical Engineers, in association with the Science Museum. ISBN 0852968450.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Hilmes, Michele and Jason Loviglio, ed. (2002). Radio reader: essays in the cultural history of radio. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415928206.

- ^ Cox, Jim (2007). The great radio sitcoms. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 9780786431465.

- ^ Spigel, Lynn (1992). Make room for TV: television and the family ideal in postwar America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226769666.

- ^ a b Tryon, Chuck (2009). Reinventing Cinema: Movies in the Age of Media Convergence. Rutgers University Press. p. 6, 9. ISBN 978-0-8135-4546-2.

- ^ Dwyer, Tim (2010). Media Convergence. Maidenhead, Berkshire, England and New York: Open University Press McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-33-522873-7.

- ^ Spigel, Lynn, Jan Olsson, ed. (2004). Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3383-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Cogburn, Jon (2002). Philosophy Through Video Games. New York, Oxon: Routledge. pp. i. ISBN 0-415-98857-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Doyle, Gillian (2002). Media Ownership: The Economics and Politics of Convergence and Concentration in the UK and European Media. (Google eBook): SAGE. ISBN 0-7619-6680-3.

- ^ Ellis, John (2000). "Scheduling: the last creative act in television?". Media Culture Society. Bournemouth University/Large Door Productions. 22 (no. 1): 25–38. doi:10.1177/016344300022001002.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ For example, in the UK: Tryhorn, Chris (21 December, 2007). "Government thinktank to tackle media convergence issues". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ And for example, in Australia: "Convergence Review". Australian Government: Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.