Reincarnation

Reincarnation is the religious or philosophical concept that the soul or spirit, after biological death, begins a new life in a new body that may be human, animal or spiritual depending on the moral quality of the previous life's actions. This doctrine is a central tenet of the Indian religions[1] and is a belief that was held by such historic figures as Pythagoras, Plato and Socrates. It is also a common belief of other religions such as Druidism, Spiritism, Theosophy, and Eckankar and is found in many tribal societies around the world, in places such as Siberia, West Africa, North America, and Australia.[2]

Although the majority of sects within the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of Kabbalah, the Cathars[citation needed], and the Shia sects such as the Alawi Shias and the Druze[3] and the Rosicrucians.[4] The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs about reincarnation that were characteristic of Neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manicheanism and Gnosticism of the Roman era, as well as the Indian religions has been the subject of recent scholarly research.[5]

In recent decades, many Europeans and North Americans have developed an interest in reincarnation.[6] Contemporary films, books, and popular songs frequently mention reincarnation. In the last decades, academic researchers have begun to explore reincarnation and published reports of children's memories of earlier lives in peer-reviewed journals and books. Skeptics are generally incredulous about this and any other claims of life after death.

Conceptual definitions

The word "reincarnation" derives from Latin, literally meaning, "entering the flesh again". The Greek equivalent metempsychosis (μετεμψύχωσις) roughly corresponds to the common English phrase "transmigration of the soul" and also usually connotes reincarnation after death,[7] as either human, animal, though emphasising the continuity of the soul, not the flesh. The term has been used by modern philosophers such as Kurt Gödel[8] and has entered the English language. Another Greek term sometimes used synonymously is palingenesis, "being born again".[9]

There is no word corresponding exactly to the English terms "rebirth", "metempsychosis", "transmigration" or "reincarnation" in the traditional languages of Pāli and Sanskrit. The entire universal process that gives rise to the cycle of death and rebirth, governed by karma, is referred to as Samsara[10] while the state one is born into, the individual process of being born or coming into the world in any way, is referred to simply as "birth" (jāti). Devas (gods) may also die and live again.[11] Here the term "reincarnation" is not strictly applicable, yet Hindu gods are said to have reincarnated (see Avatar): Lord Vishnu is known for his ten incarnations, the Dashavatars. Celtic religion seems to have had reincarnating gods also. Many Christians regard Jesus as a divine incarnation. Some Christians and Muslims believe he and some prophets may incarnate again. Most Christians, however, believe that Jesus will come again in the Second Coming at the end of the world, although this is not a reincarnation. Some ghulat Shi'a Muslim sects also regard their founders as in some special sense divine incarnations (hulul).

Philosophical and religious beliefs regarding the existence or non-existence of an unchanging "self" have a direct bearing on how reincarnation is viewed within a given tradition. The Buddha lived at a time of great philosophical creativity in India when many conceptions of the nature of life and death were proposed. Some were materialist, holding that there was no existence and that the self is annihilated upon death. Others believed in a form of cyclic existence, where a being is born, lives, dies and then is reborn, but in the context of a type of determinism or fatalism in which karma played no role. Others were "eternalists", postulating an eternally existent self or soul comparable to that in Judaic monotheism: the ātman survives death and reincarnates as another living being, based on its karmic inheritance. This is the idea that has become dominant (with certain modifications) in modern Hinduism.

The Buddhist concept of reincarnation differs from others in that there is no eternal "soul", "spirit" or "self" but only a "stream of consciousness" that links life with life. The actual process of change from one life to the next is called punarbhava (Sanskrit) or punabbhava (Pāli), literally "becoming again", or more briefly bhava, "becoming", and some English-speaking Buddhists prefer the term "rebirth" or "re-becoming" to render this term as they take "reincarnation" to imply a fixed entity that is reborn.[12] Popular Jain cosmology and Buddhist cosmology as well as a number of schools of Hinduism posit rebirth in many worlds and in varied forms. In Buddhist tradition the process occurs across five or six realms of existence,[13] including the human, any kind of animal and several types of supernatural being. It is said in Tibetan Buddhism that it is very rare for a person to be reborn in the immediate next life as a human[14]

Gilgul, Gilgul neshamot or Gilgulei Ha Neshamot (Heb. גלגול הנשמות) refers to the concept of reincarnation in Kabbalistic Judaism, found in much Yiddish literature among Ashkenazi Jews. Gilgul means "cycle" and neshamot is "souls." The equivalent Arabic term is tanasukh:[15] the belief is found among Shi'a ghulat Muslim sects.

History

Origins

The origins of the notion of reincarnation are obscure. They apparently date to the Iron Age (around 1200 BCE).[16] Discussion of the subject appears in the philosophical traditions of India (including the Indus Valley) and Greece (including the Asia Minor) from about the 6th century BCE. Also during the Iron Age, the Greek Pre-Socratics discussed reincarnation, and the Celtic Druids are also reported to have taught a doctrine of reincarnation.[17]

The ideas associated with reincarnation may have arisen independently in different regions, or they might have spread as a result of cultural contact. Proponents of cultural transmission have looked for links between Iron Age Celtic, Greek and Vedic philosophy and religion,[18] some[who?] even suggesting that belief in reincarnation was present in Proto-Indo-European religion.[dubious – discuss][19] In ancient European, Iranian and Indian agricultural cultures, the life cycles of birth, death, and rebirth were recoginized as a replica of natural agricultural cycles.[20]

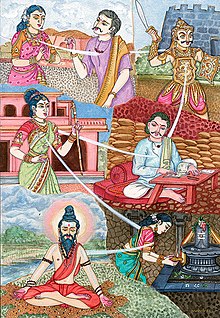

Early Jainism, Hinduism and Buddhism

Patrick Olivelle asserts that the origin of the concept of the cycle of birth and death, the concept of samsara, and the concept of liberation in the Indian tradition, were in part the creation of the non-Vedic Shramana tradition.[21] Another possibility are the prehistoric Dravidian traditions of South India.[22] Some scholars suggest that the idea is original to the Buddha.[23]

In Jainism, the soul and matter are considered eternal, uncreated and perpetual. There is a constant interplay between the two, resulting in bewildering cosmic manifestations in material, psychic and emotional spheres around us. This led to the theories of transmigration and rebirth. Changes but not total annihilation of spirit and matter is the basic postulate of Jain philosophy. The life as we know now, after death therefore moves on to another form of life based on the merits and demerits it accumulated in its current life. The path to becoming a supreme soul is to practice non-violence and be truthful.[24]

In Hinduism, the holy book Rigveda, the oldest extant Indo-Aryan text, numerous references are made to rebirths,[25] although it portrays reincarnation as "redeaths" (punarmrtyu).[citation needed] One verse reads "Each death repeats the death of the primordial man (purusa), which was also the first sacrifice" (RV 10:90).[26] Another excerpt from the Rig Veda states (Book 10 Part 02, Hymn XVI):

- "Burn him not up, nor quite consume him, Agni: let not his body or his skin be scattered. O Jatavedas, when thou hast matured him, then send him on his way unto the Fathers... let thy fierce flame, thy glowing splendour, burn him With thine auspicious forms, o Jatavedas, bear this man to the region of the pious... Again, O Agni, to the Fathers send him who, offered in thee, goes with our oblations. Wearing new life let him increase his offspring: let him rejoin a body, Jatavedas."[citation needed][27]

Indian discussion of reincarnation enters the historical record from about the 6th century BCE, with the development of the Advaita Vedanta tradition in the early Upanishads (around the middle of the first millennium BCE), Gautama Buddha (623-543 BCE)[28] as well as Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism.[29]

The systematic attempt to attain first-hand knowledge of past lives has been developed in various ways in different places. The early Buddhist texts discuss techniques for recalling previous births, predicated on the development of high levels of meditative concentration.[30] The later Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, which incorporated elements of Buddhist thought,[31] give similar instructions on how to attain the ability.[32] The Buddha reportedly warned that this experience can be misleading and should be interpreted with care.[33] Tibetan Buddhism has developed a unique 'science' of death and rebirth, a good deal of which is set down in what is popularly known as The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Early Greece

Early Greek discussion of the concept likewise dates to the 6th century BCE. An early Greek thinker known to have considered rebirth is Pherecydes of Syros (fl. 540 BCE).[34] His younger contemporary Pythagoras (c. 570-c. 495 BCE[35]), its first famous exponent, instituted societies for its diffusion. Plato (428/427 – 348/347 BCE) presented accounts of reincarnation in his works, particularly the Myth of Er.

Authorities have not agreed on how the notion arose in Greece: sometimes Pythagoras is said to have been Pherecydes' pupil, sometimes to have introduced it with the doctrine of Orphism, a Thracian religion that was to be important in the diffusion of reincarnation, or else to have brought the teaching from India. In Phaedo, Plato makes his teacher Socrates, prior to his death, state; "I am confident that there truly is such a thing as living again, and that the living spring from the dead." However Xenophon does not mention Socrates as believing in reincarnation and Plato may have systematised Socrates' thought with concepts he took directly from Pythagoreanism or Orphism.

Classical Antiquity

The Orphic religion, which taught reincarnation, first appeared in Thrace in north-eastern Greece and Bulgaria, about the 6th century BC, organized itself into mystery schools at Eleusis and elsewhere, and produced a copious literature.[36][37][38] Orpheus, its legendary founder, is said to have taught that the immortal soul aspires to freedom while the body holds it prisoner. The wheel of birth revolves, the soul alternates between freedom and captivity round the wide circle of necessity. Orpheus proclaimed the need of the grace of the gods, Dionysus in particular, and of self-purification until the soul has completed the spiral ascent of destiny to live for ever.

An association between Pythagorean philosophy and reincarnation was routinely accepted throughout antiquity. In the Republic Plato makes Socrates tell how Er, the son of Armenius, miraculously returned to life on the twelfth day after death and recounted the secrets of the other world. There are myths and theories to the same effect in other dialogues, in the Chariot allegory of the Phaedrus, in the Meno, Timaeus and Laws. The soul, once separated from the body, spends an indeterminate amount of time in "formland" (see The Allegory of the Cave in The Republic) and then assumes another body.

In later Greek literature the doctrine is mentioned in a fragment of Menander[39] and satirized by Lucian.[40] In Roman literature it is found as early as Ennius,[41] who, in a lost passage of his Annals, told how he had seen Homer in a dream, who had assured him that the same soul which had animated both the poets had once belonged to a peacock. Persius in his satires (vi. 9) laughs at this: it is referred to also by Lucretius[42] and Horace.[43]

Virgil works the idea into his account of the Underworld in the sixth book of the Aeneid.[44] It persists down to the late classic thinkers, Plotinus and the other Neoplatonists. In the Hermetica, a Graeco-Egyptian series of writings on cosmology and spirituality attributed to Hermes Trismegistus/Thoth, the doctrine of reincarnation is central.

In Greco-Roman thought, the concept of metempsychosis disappeared with the rise of Early Christianity, reincarnation being incompatible with the Christian core doctrine of salvation of the faithful after death. It has been suggested that some of the early Church Fathers, especially Origen still entertained a belief in the possibility of reincarnation, but evidence is tenuous, and the writings of Origen as they have come down to us speak explicitly against it.[45]

Some early Christian Gnostic sects professed reincarnation. The Sethians and followers of Valentinus believed in it.[46] The followers of Bardaisan of Mesopotamia, a sect of the 2nd century deemed heretical by the Catholic Church, drew upon Chaldean astrology, to which Bardaisan's son Harmonius, educated in Athens, added Greek ideas including a sort of metempsychosis. Another such teacher was Basilides (132–? CE/AD), known to us through the criticisms of Irenaeus and the work of Clement of Alexandria. (see also Neoplatonism and Gnosticism and Buddhism and Gnosticism)

In the third Christian century Manichaeism spread both east and west from Babylonia, then within the Sassanid Empire, where its founder Mani lived about 216–276. Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 AD. Noting Mani's early travels to the Kushan Empire and other Buddhist influences in Manichaeism, Richard Foltz[47] attributes Mani's teaching of reincarnation to Buddhist influence. However the inter-relation of Manicheanism, Orphism, Gnosticism and neo-Platonism is far from clear.

The Celts

In the 1st century BC Alexander Cornelius Polyhistor wrote:

The Pythagorean doctrine prevails among the Gauls' teaching that the souls of men are immortal, and that after a fixed number of years they will enter into another body.

Julius Caesar recorded that the druids of Gaul, Britain and Ireland had metempsychosis as one of their core doctrines:[48]

The principal point of their doctrine is that the soul does not die and that after death it passes from one body into another..... the main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed.

Judaism

In Judaism, Rabbi Isaac Luria was said to know the past lives of each person through his semi-prophetic abilities. This was also true of the Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, the Seer of Lublin, and other Hasidic masters and Sefardic Kabbalists.[citation needed]

Taoism

Taoist documents from as early as the Han Dynasty claimed that Lao Tzu appeared on earth as different persons in different times beginning in the legendary era of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors. The (ca. 3rd century BC) Chuang Tzu states: "Birth is not a beginning; death is not an end. There is existence without limitation; there is continuity without a starting-point. Existence without limitation is Space. Continuity without a starting point is Time. There is birth, there is death, there is issuing forth, there is entering in."[49]

Middle Ages

Around the 11-12th century several reincarnationist movements were persecuted as heresies, through the establishment of the Inquisition in the Latin west. These included the Cathar, Paterene or Albigensian church of western Europe, the Paulician movement, which arose in Armenia,[50] and the Bogomils in Bulgaria.[51]

Christian sects such as the Bogomils and the Cathars, who professed reincarnation and other gnostic beliefs, were referred to as "Manichean", and are today sometimes described by scholars as "Neo-Manichean".[52] As there is no known Manichaean mythology or terminology in the writings of these groups there has been some dispute among historians as to whether these groups truly were descendants of Manichaeism.[53]

Norse mythology

Reincarnation also appears in Norse mythology, in the Poetic Edda. The editor of the Poetic Edda says that Helgi Hjörvarðsson and his mistress, the valkyrie Sváfa, whose love story is told in the poem Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar, were reborn as Helgi Hundingsbane and the valkyrie Sigrún. Helgi and Sigrún's love story is the matter of a part of the Völsunga saga and the lays Helgakviða Hundingsbana I and II. They were reborn a second time as Helgi Haddingjaskati and the valkyrie Kára, but unfortunately their story, Káruljóð, only survives in a probably modified form in the Hrómundar saga Gripssonar.

The belief in reincarnation may have been commonplace among the Norse since the annotator of the Poetic Edda wrote that people formerly used to believe in it:

Sigrun was early dead of sorrow and grief. It was believed in olden times that people were born again, but that is now called old wives' folly. Of Helgi and Sigrun it is said that they were born again; he became Helgi Haddingjaskati, and she Kara the daughter of Halfdan, as is told in the Lay of Kara, and she was a Valkyrie.[54]

Renaissance and Early Modern period

While reincarnation has been a matter of faith in some communities from an early date it has also frequently been argued for on principle, as Plato does when he argues that the number of souls must be finite because souls are indestructible,[55] Benjamin Franklin held a similar view.[56] Sometimes such convictions, as in Socrates' case, arise from a more general personal faith, at other times from anecdotal evidence such as Plato makes Socrates offer in the Myth of Er.

During the Renaissance translations of Plato, the Hermetica and other works fostered new European interest in reincarnation. Marsilio Ficino[57] argued that Plato's references to reincarnation were intended allegorically, Shakespeare made fun[58] but Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake by authorities after being found guilty of heresy by the Roman Inquisition for his teachings.[59] But the Greek philosophical works remained available and, particularly in north Europe, were discussed by groups such as the Cambridge Platonists.

19th to 20th centuries

By the 19th century the philosophers Schopenhauer[61] and Nietzsche[62] could access the Indian scriptures for discussion of the doctrine of reincarnation, which recommended itself to the American Transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson and was adapted by Francis Bowen into Christian Metempsychosis.[63]

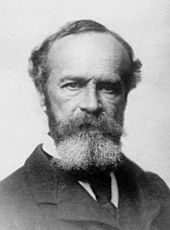

By the early 20th century, interest in reincarnation had been introduced into the nascent discipline of psychology, largely due to the influence of William James, who raised aspects of the philosophy of mind, comparative religion, the psychology of religious experience and the nature of empiricism.[64] James was influential in the founding of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) in New York City in 1885, three years after the British Society for Psychical Research (SPR) was inaugurated in London,[60] leading to systematic, critical investigation of paranormal phenomena.

At this time popular awareness of the idea of reincarnation was boosted by the Theosophical Society's dissemination of systematised and universalised Indian concepts and also by the influence of magical societies like The Golden Dawn. Notable personalities like Annie Besant, W. B. Yeats and Dion Fortune made the subject almost as familiar an element of the popular culture of the west as of the east. By 1924 the subject could be satirised in popular children's books.[65]

Théodore Flournoy was among the first to study a claim of past-life recall in the course of his investigation of the medium Hélène Smith, published in 1900, in which he defined the possibility of cryptomnesia in such accounts.[66] Carl Gustav Jung, like Flournoy based in Switzerland, also emulated him in his thesis based on a study of cryptomnesia in psychism. Later Jung would emphasise the importance of the persistence of memory and ego in psychological study of reincarnation: "This concept of rebirth necessarily implies the continuity of personality... (that) one is able, at least potentially, to remember that one has lived through previous existences, and that these existences were one's own...".[63] Hypnosis, used in psychoanalysis for retrieving forgotten memories, was eventually tried as a means of studying the phenomenon of past life recall.

Reincarnation research

Psychiatrist Ian Stevenson, from the University of Virginia, investigated many reports of young children who claimed to remember a past life. He conducted more than 2,500 case studies over a period of 40 years and published twelve books, including Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation and Where Reincarnation and Biology Intersect. Stevenson methodically documented each child's statements and then identified the deceased person the child identified with, and verified the facts of the deceased person's life that matched the child's memory. He also matched birthmarks and birth defects to wounds and scars on the deceased, verified by medical records such as autopsy photographs, in Reincarnation and Biology.[67]

Stevenson searched for disconfirming evidence and alternative explanations for the reports, and believed that his strict methods ruled out all possible "normal" explanations for the child’s memories.[68] However, a significant majority of Stevenson's reported cases of reincarnation originated in Eastern societies, where dominant religions often permit the concept of reincarnation. Following this type of criticism, Stevenson published a book on European Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Other people who have undertaken reincarnation research include Jim B. Tucker, Satwant Pasricha, Godwin Samararatne, and Erlendur Haraldsson.

Skeptics such as Paul Edwards have analyzed many of these accounts, and called them anecdotal,[69] while also suggesting that claims of evidence for reincarnation originate from selective thinking and from the false memories that often result from one's own belief system and basic fears, and thus cannot be counted as empirical evidence. Carl Sagan referred to examples apparently from Stevenson's investigations in his book The Demon-Haunted World as an example of carefully collected empirical data, though he rejected reincarnation as a parsimonious explanation for the stories.[70]

Objection to claims of reincarnation include the facts that the vast majority of people do not remember previous lives and there is no mechanism known to modern science that would enable a personality to survive death and travel to another body. Researchers such as Stevenson have acknowledged these limitations.[71]

Reincarnation in the West

During recent decades, many people in the West have developed an interest in reincarnation.[6] Feature films, such as The Reincarnation of Peter Proud, Dead Again, Kundun, Fluke, What Dreams May Come and Birth, contemporary books by authors such as Carol Bowman and Vicki Mackenzie, as well as popular songs, deal with reincarnation.

Recent studies have indicated that some Westerners accept the idea of reincarnation[6] including certain contemporary Christians,[72] modern Neopagans, followers of Spiritism, Theosophists and students of esoteric philosophies such as Kabbalah, and Gnostic and Esoteric Christianity as well as of Indian religions. Demographic survey data from 1999-2002 shows a significant minority of people from Europe and America, where there is reasonable freedom of thought and access to ideas but no outstanding recent reincarnationist tradition, believe we had a life before we were born, will survive death and be born again physically. The mean for the Nordic countries is 22%.[73] The belief in reincarnation is particularly high in the Baltic countries, with Lithuania having the highest figure for the whole of Europe, 44%. The lowest figure is in East Germany, 12%. In Russia, about one-third believes in reincarnation. The effect of communist anti-religious ideas on the beliefs of the populations of Eastern Europe seems to have been rather slight, if any, except apparently in East Germany.[73] Overall, 22% of respondents in Western Europe believe in reincarnation.[73] According to a 2005 Gallup poll 20 percent of U.S. adults believe in reincarnation. Recent surveys by the Barna Group, a Christian research nonprofit organization, have found that a quarter of U.S. Christians, including 10 percent of all born-again Christians, embrace the idea.[74]

Skeptic Carl Sagan asked the Dalai Lama what he would do if a fundamental tenet of his religion (reincarnation) were definitively disproved by science. The Dalai Lama answered; "if science can disprove reincarnation, Tibetan Buddhism would abandon reincarnation... but it's going to be mighty hard to disprove reincarnation."[75]

Ian Stevenson reported that belief in reincarnation is held (with variations in details) by adherents of almost all major religions except Christianity and Islam. In addition, between 20 and 30 percent of persons in western countries who may be nominal Christians also believe in reincarnation.[76]

One 1999 study by Walter and Waterhouse reviewed the previous data on the level of reincarnation belief and performed a set of thirty in-depth interviews in Britain among people who did not belong to a religion advocating reincarnation.[77] The authors reported that surveys have found about one fifth to one quarter of Europeans have some level of belief in reincarnation, with similar results found in the USA. In the interviewed group, the belief in the existence of this phenomenon appeared independent of their age, or the type of religion that these people belonged to, with most being Christians. The beliefs of this group also did not appear to contain any more than usual of "new age" ideas (broadly defined) and the authors interpreted their ideas on reincarnation as "one way of tackling issues of suffering", but noted that this seemed to have little effect on their private lives.

Waterhouse also published a detailed discussion of beliefs expressed in the interviews.[78] She noted that although most people "hold their belief in reincarnation quite lightly" and were unclear on the details of their ideas, personal experiences such as past-life memories and near-death experiences had influenced most believers, although only a few had direct experience of these phenomena. Waterhouse analyzed the influences of second-hand accounts of reincarnation, writing that most of the people in the survey had heard other people's accounts of past-lives from regression hypnosis and dreams and found these fascinating, feeling that there "must be something in it" if other people were having such experiences.

Contemporary religious philosophies

Hinduism

Reincarnation - known as Punarjanma is one of the core beliefs of Hinduism that is generally accepted by many of its practitioners.[79]

Reincarnation is the natural process of birth, death and rebirth. Hindus believe that the Jiva or Atman (soul) is intrinsically pure. Howevever, because of the layers of I-ness and My-ness, the jiva goes through transmigration in the cycle of births and deaths. Death destroys the physical body, but not the jiva. The jiva is eternal. It takes on another body[80] with respect to its karmas. Every karma produces a result which must be experienced either in this or some future life. As long as the jiva is enveloped in ignorance, it remains attached to material desires and subject to the cycles of births and deaths (Samsara).

There is no permanent heaven or hell in Hinduism. After services in the afterlife, the jiva enters the karma and rebirth system, reborn as an animal, a human or a divinity. This reincarnation continues until mokṣa, the final release, is gained.[81]

The Bhagavad Gita states;

Never was there a time when I did not exist, nor you, nor all these kings; nor in the future shall any of us cease to be. As the embodied soul continuously passes, in this body, from childhood to youth to old age, the soul similarly passes into another body at death. A sober person is not bewildered by such a change. (2: 12-13)

and,

Worn-out garments are shed by the body; Worn-out bodies are shed by the dweller within the body. New bodies are donned by the dweller, like garments. (2:22)[82]

According to the Hindu sage Adi Shankaracharya, the world - as we ordinarily understand it - is like a dream: fleeting and illusory. To be trapped in samsara (the cycle of birth and death) is a result of ignorance of the true nature of our existence. It is ignorance (avidya) of one's true self that leads to ego-consciousness, grounding one in desire and a perpetual chain of reincarnation. The idea is intricately linked to action (karma), a concept first recorded in the Upanishads. Every action has a reaction and the force determines one's next incarnation. One is reborn through desire: a person desires to be born because he or she wants to enjoy a body,[83] which can never bring deep, lasting happiness or peace (ānanda). After many births every person becomes dissatisfied and begins to seek higher forms of happiness through spiritual experience. When, after spiritual practice (sādhanā), a person realizes that the true "self" is the immortal soul rather than the body or the ego all desires for the pleasures of the world will vanish since they will seem insipid compared to spiritual ānanda. When all desire has vanished the person will not be born again.[84] When the cycle of rebirth thus comes to an end, a person is said to have attained liberation (moksha).[85] All schools agree this implies the cessation of worldly desires and freedom from the cycle of birth and death, though the exact definition differs. Followers of the Advaita Vedanta school believe they will spend eternity absorbed in the perfect peace and happiness of the realization that all existence is One Brahman of which the soul is part. Dvaita schools perform worship with the goal of spending eternity in a spiritual world or heaven (loka) in the blessed company of the Supreme Being.[86]

Reasons for Reincarnation

Hindus provide several reasons why the jiva takes on various physical bodies[87]:

- To experience the fruits of one's karmas: This is the main reason for rebirth. Sattvika (good or righteous) karmas reward one with the pleasures of Svarga. Rajas (pleasure-seeking) karmas reward one with mrutyuloka (mortal realm or earth). And Tamas karmas (actions related to inertia, laziness and evil) condemn one to patala-loka.

- To satisfy one's desires: When a person indulges in material pleasures, he or she subsequently develops a stronger desire to enjoy more of it (Vāsanā). This unending craving to satisfy one's desires causes the jiva to assume new physical bodies.

- To complete one's unfinished sadhana: When an aspirant making spiritual efforts for liberation from maya dies without attaining his or her goal, the jiva gets as a natural cause-effect another human body to complete its sadhana.

- To fulfil a debt: When a jiva is indebted to another jiva, it gets a human birth to fulfil its debt and receive what is owed to it. The jiva comes in the form of a relative, friend or an enemy.

- To undergo sufferings because of a great soul's curse: A person's grave error or sin may incur the wrath or displeasure of God or a Rishi. This results in the jiva of that person getting another birth, not necessarily into a human body.

- To attain moksha: By the grace and compassion of God or a God-realized guru, a jiva gets a human body to purge itself of the layers of base instincts.[88]

Jainism

Jainism is historically connected with the sramana tradition with which the earliest mentions of reincarnation are associated.[89]

Karma forms a central and fundamental part of Jain faith, being intricately connected to other of its philosophical concepts like transmigration, reincarnation, liberation, non-violence (ahiṃsā) and non-attachment, among others. Actions are seen to have consequences: some immediate, some delayed, even into future incarnations. So the doctrine of karma is not considered simply in relation to one life-time, but also in relation to both future incarnations and past lives.[90] Uttarādhyayana-sūtra 3.3–4 states: "The jīva or the soul is sometimes born in the world of gods, sometimes in hell. Sometimes it acquires the body of a demon; all this happens on account of its karma. This jīva sometimes takes birth as a worm, as an insect or as an ant."[91] The text further states (32.7): "Karma is the root of birth and death. The souls bound by karma go round and round in the cycle of existence."[91]

Actions and emotions in the current lifetime affect future incarnations depending on the nature of the particular karma. For example, a good and virtuous life indicates a latent desire to experience good and virtuous themes of life. Therefore, such a person attracts karma that ensures that his future births will allow him to experience and manifest his virtues and good feelings unhindered.[92] In this case, he may take birth in heaven or in a prosperous and virtuous human family. On the other hand, a person who has indulged in immoral deeds, or with a cruel disposition, indicates a latent desire to experience cruel themes of life.[93] As a natural consequence, he will attract karma which will ensure that he is reincarnated in hell, or in lower life forms, to enable his soul to experience the cruel themes of life.[93]

There is no retribution, judgment or reward involved but a natural consequences of the choices in life made either knowingly or unknowingly. Hence, whatever suffering or pleasure that a soul may be experiencing in its present life is on account of choices that it has made in the past.[94] As a result of this doctrine, Jainism attributes supreme importance to pure thinking and moral behavior.[95]

The Jain texts postulate four gatis, that is states-of-existence or birth-categories, within which the soul transmigrates. The four gatis are: deva (demi-gods), manuṣya (humans), nāraki (hell beings) and tiryañca (animals, plants and micro-organisms).[96] The four gatis have four corresponding realms or habitation levels in the vertically tiered Jain universe: demi-gods occupy the higher levels where the heavens are situated; humans, plants and animals occupy the middle levels; and hellish beings occupy the lower levels where seven hells are situated.[96]

Single-sensed souls, however, called nigoda,[97] and element-bodied souls pervade all tiers of this universe. Nigodas are souls at the bottom end of the existential hierarchy. They are so tiny and undifferentiated, that they lack even individual bodies, living in colonies. According to Jain texts, this infinity of nigodas can also be found in plant tissues, root vegetables and animal bodies.[98] Depending on its karma, a soul transmigrates and reincarnates within the scope of this cosmology of destinies. The four main destinies are further divided into sub-categories and still smaller sub-sub-categories. In all, Jain texts speak of a cycle of 8.4 million birth destinies in which souls find themselves again and again as they cycle within samsara.[99]

In Jainism, God has no role to play in an individual's destiny; one's personal destiny is not seen as a consequence of any system of reward or punishment, but rather as a result of its own personal karma. A text from a volume of the ancient Jain canon, Bhagvati sūtra 8.9.9, links specific states of existence to specific karmas. Violent deeds, killing of creatures having five sense organs, eating fish, and so on, lead to rebirth in hell. Deception, fraud and falsehood leads to rebirth in the animal and vegetable world. Kindness, compassion and humble character result in human birth; while austerities and the making and keeping of vows leads to rebirth in heaven.[100]

Each soul is thus responsible for its own predicament, as well as its own salvation. Accumulated karma represent a sum total of all unfulfilled desires, attachments and aspirations of a soul.[101][102] It enables the soul to experience the various themes of the lives that it desires to experience.[101] Hence a soul may transmigrate from one life form to another for countless of years, taking with it the karma that it has earned, until it finds conditions that bring about the required fruits. In certain philosophies, heavens and hells are often viewed as places for eternal salvation or eternal damnation for good and bad deeds. But according to Jainism, such places, including the earth are simply the places which allow the soul to experience its unfulfilled karma.[103]

Buddhism

The early Buddhist texts make it clear that there is no permanent consciousness that moves from life to life.[104] Gautama Buddha taught a distinct concept of rebirth constrained by the concepts of anattā, that there is no irreducible ātman or "self" tying these lives together (which serves as a contrast to Hinduism, where everything is connected, and in a sense, "everything is everything"),[105] and anicca, that all compounded things are subject to dissolution, including all the components of the human person and personality.

In Buddhist doctrine the evolving consciousness (Pali: samvattanika-viññana)[106][107] or stream of consciousness (Pali: viññana-sotam,[108] Sanskrit: vijñāna-srotām, vijñāna-santāna, or citta-santāna) upon death (or "the dissolution of the aggregates" (P. khandhas, S. skandhas)), becomes one of the contributing causes for the arising of a new aggregation. At the death of one personality, a new one comes into being, much as the flame of a dying candle can serve to light the flame of another.[109][110] The consciousness in the new person is neither identical to nor entirely different from that in the deceased but the two form a causal continuum or stream. Transmigration is the effect of karma (kamma)[111][112] or volitional action.[113] The basic cause is the abiding of consciousness in ignorance (Pali: avijja, Sanskrit: avidya): when ignorance is uprooted rebirth ceases.[114]

The Buddha's detailed conception of the connections between action (karma), rebirth and causality is set out in the twelve links of dependent origination. The empirical, changing self does not only affect the world about it, it also generates, consciously and unconsciously, a subjective image of the world in which it lives as 'reality'. It "tunes in" to a particular level of consciousness which has a particular range of objects, selectively notices such objects and forms a partial model of reality in which the ego is the crucial reference point. Vipassana meditation uses "bare attention" to mind-states without interfering, owning or judging. Observation reveals each moment as an experience of an individual mind-state such as a thought, a memory, a feeling or a perception that arises, exists and ceases. This limits the power of desire, which, according to the second noble truth of Buddhism, is the cause of suffering (dukkha), and leads to Nirvana (nibbana, vanishing (of the self-idea)) in which self-oriented models are transcended and "the world stops".[115] Thus consciousness is a continuous birth and death of mind-states: rebirth is the persistence of this process.

While all Buddhist traditions accept rebirth there is no unified view about precisely how events unfold after death. The Tibetan schools hold to the notion of a bardo (intermediate state) that can last up to forty-nine days. An accomplished or realized practitioner (by maintaining conscious awareness during the death process) can choose to return to samsara, that many lamas choose to be born again and again as humans and are called tulkus or incarnate lamas.[citation needed] The Sarvastivada school believed that between death and rebirth there is a sort of limbo in which beings do not yet reap the consequences of their previous actions but may still influence their rebirth. The death process and this intermediate state were believed to offer a uniquely favourable opportunity for spiritual awakening. Theravada Buddhism generally denies there is an intermediate state, though some early Buddhist texts seem to support it,[116][117] but asserts that rebirth is immediate.

Some schools conclude that karma continues to exist and adhere to the person until it works out its consequences. For the Sautrantika school each act "perfumes" the individual or "plants a seed" that later germinates. In another view remaining impure aggregates, skandhas, reform consciousness. Tibetan Buddhism stresses the state of mind at the time of death. To die with a peaceful mind will stimulate a virtuous seed and a fortunate rebirth, a disturbed mind will stimulate a non-virtuous seed and an unfortunate rebirth.[118] The medieval Pali scholar Buddhaghosa labeled the consciousness that constitutes the condition for a new birth as described in the early texts "rebirth-linking consciousness" (patisandhi).

Sant mystics and Sikhism

Reincarnation remained a tenet of the Sant Bhakti movement and of related mystics on the frontiers of Islam and Hinduism such as the Baul minstrels, the Kabir panth and the Sikh Brotherhood. Sikhs believe the soul is passed from one body to another until Liberation. If we perform good deeds and actions and remember the Creator, we attain a better life while, if we carry out evil actions and sinful deeds, we will be incarnated in “lower” life forms. God may pardon wrongs and release us.[119] Otherwise reincarnation is due to the law of cause and effect but does not create any caste or differences among people. Eckankar is a Western presentation of Sant mysticism.[120] It teaches that the soul is eternal and either chooses an incarnation for growth or else an incarnation is imposed because of Karma. The soul is perfected through a series of incarnations until it arrives at "Personal Mastery".

African Vodun

The Yoruba believe in reincarnation within the family. The names Babatunde (father returns), Yetunde (Mother returns), Babatunji (Father wakes once again) and Sotunde (The wise man returns) all offer vivid evidence of the Ifa concept of familial or lineal rebirth. There is no simple guarantee that your grandfather or great uncle will "come back" in the birth of your child, however.

Whenever the time arrives for a spirit to return to Earth (otherwise known as The Marketplace) through the conception of a new life in the direct bloodline of the family, one of the component entities of a person's being returns, while the other remains in Heaven (Ikole Orun). The spirit that returns does so in the form of a Guardian Ori. One's Guardian Ori, which is represented and contained in the crown of the head, represents not only the spirit and energy of one's previous blood relative, but the accumulated wisdom he or she has acquired through a myriad of lifetimes. This is not to be confused with one’s spiritual Ori, which contains personal destiny, but instead refers to the coming back to The Marketplace of one's personal blood Ori through one's new life and experiences. The explanation in The Way of the Orisa[121] was really quite clear. The Primary Ancestor (which should be identified in your Itefa (Life Path Reading)) becomes - if you are aware and work with that specific energy - a “guide” for the individual throughout their lifetime. At the end of that life they return to their identical spirit self and merge into one, taking the additional knowledge gained from their experience with the individual as a form of payment.

Islam

The idea of reincarnation is accepted by a few Muslim sects, particularly of the (Ghulat),[122] and by other sects in the Muslim world such as Druzes.[123] Historically, South Asian Isma'ilis performed chantas yearly, one of which is for sins committed in past lives.[124] (Aga Khan IV) Sinan ibn Salman ibn Muhammad, also known as Rashid al-Din Sinan, (r. 1162-92) subscribed to the transmigration of souls as a tenet of the Alawi,[125] who are thought to have been influenced by Isma'ilism.

Modern Sufis who embrace the idea of reincarnation include Bawa Muhaiyadeen.[126] However Hazrat Inayat Khan has criticized the idea as unhelpful to the spiritual seeker.[127]

Judaism

Reincarnation is not an essential tenet of traditional Judaism.[128] It is not mentioned in the Tanakh ("Hebrew Bible"), the classical rabbinical works (Mishnah and Talmud), or Maimonides' 13 Principles of Faith, though the tale of the Ten Martyrs in the Yom Kippur liturgy, who were killed by Romans to atone for the souls of the ten brothers of Joseph, is read in Ashkenazi Orthodox Jewish communities. Medieval Jewish Rationalist philosophers discussed the issue, often in rejection. However, Jewish mystical texts (the Kabbalah), from their classic Medieval canon onwards, teach a belief in Gilgul Neshamot (Hebrew for metempsychosis of souls: literally "soul cycle", plural "gilgulim"). It is a common belief in contemporary Hasidic Judaism, which regards the Kabbalah as sacred and authoritative, though unstressed in favour of a more innate psychological mysticism. Kabbalah also teaches that "The soul of Moses is reincarnated in every generation".[129] Other, Non-Hasidic, Orthodox Jewish groups while not placing a heavy emphasis on reincarnation, do acknowledge it as a valid teaching.[130] Its popularisation entered modern secular Yiddish literature and folk motif.

The 16th-century mystical renaissance in communal Safed replaced scholastic Rationalism as mainstream traditional Jewish theology, both in scholarly circles and in the popular imagination. References to gilgul in former Kabbalah became systemised as part of the metaphysical purpose of creation. Isaac Luria (the Ari) brought the issue to the centre of his new mystical articulation, for the first time, and advocated identification of the reincarnations of historic Jewish figures that were compiled by Haim Vital in his Shaar HaGilgulim.[131] Gilgul is contrasted with the other processes in Kabbalah of Ibbur ("pregnancy"), the attachment of a second soul to an individual for (or by) good means, and Dybuk ("possession"), the attachment of a spirit, demon, etc. to an individual for (or by) "bad" means.

In Lurianic Kabbalah, reincarnation is not retributive or fatalistic, but an expression of Divine compassion, the microcosm of the doctrine of cosmic rectification of creation. Gilgul is a heavenly agreement with the individual soul, conditional upon circumstances. Luria's radical system focused on rectification of the Divine soul, played out through Creation. The true essence of anything is the divine spark within that gives it existence. Even a stone or leaf possesses such a soul that "came into this world to receive a rectification". A human soul may occasionally be exiled into lower inanimate, vegetative or animal creations. The most basic component of the soul, the nefesh, must leave at the cessation of blood production. There are four other soul components and different nations of the world possess different forms of souls with different purposes. Each Jewish soul is reincarnated in order to fulfil each of the 613 Mosaic commandments that elevate a particular spark of holiness associated with each commandment. Once all the Sparks are redeemed to their spiritual source, the Messianic Era begins. Non-Jewish observance of the 7 Laws of Noah assists the Jewish people, though Biblical adversaries of Israel reincarnate to oppose.

Among the many rabbis who accepted reincarnation are Nahmanides (the Ramban) and Rabbenu Bahya ben Asher, Levi ibn Habib (the Ralbah), Shelomoh Alkabez, Moses Cordovero, Moses Chaim Luzzatto, the Baal Shem Tov and later Hasidic masters, and the Mitnagdic Vilna Gaon and Chaim Volozhin and their school, Ben Ish Chai of Baghdad and the Baba Sali. Rabbis who have rejected the idea include Saadia Gaon, David Kimhi, Hasdai Crescas, Joseph Albo, Abraham ibn Daud and Leon de Modena. Among the Geonim, Hai Gaon argued in favour of gilgulim.

Native American nations

Reincarnation is an intrinsic part of many Native American and Inuit[132] traditions.[citation needed] In the now heavily Christian Polar North (now mainly parts of Greenland and Nunavut), the concept of reincarnation is enshrined in the Inuit language.[citation needed][133]

The following is a story of human-to-human reincarnation as told by Thunder Cloud, a Winnebago shaman referred to as T. C. in the narrative. Here T. C. talks about his two previous lives and how he died and came back again to this his third lifetime. He describes his time between lives, when he was “blessed” by Earth Maker and all the abiding spirits and given special powers, including the ability to heal the sick.

T. C.’s Account of His Two Reincarnations

I (my ghost) was taken to the place where the sun sets (the west). ... While at that place, I thought I would come back to earth again, and the old man with whom I was staying said to me, “My son, did you not speak about wanting to go to the earth again?” I had, as a matter of fact, only thought of it, yet he knew what I wanted. Then he said to me, “You can go, but you must ask the chief first.” Then I went and told the chief of the village of my desire, and he said to me, “You may go and obtain your revenge upon the people who killed your relatives and you.” Then I was brought down to earth. ... There I lived until I died of old age. ... As I was lying [in my grave], someone said to me, “Come, let us go away.” So then we went toward the setting of the sun. There we came to a village where we met all the dead. ... From that place I came to this earth again for the third time, and here I am. (Radin, 1923)[134]

Christianity

Though the major Christian denominations reject the concept of reincarnation, a large number of Christians profess the belief. In a survey by the Pew Forum in 2009, 24% of American Christians expressed a belief in reincarnation.[135] In a 1981 Survey in Europe 31% of regular churchgoing Catholics expressed a belief in reincarnation.[136]

Geddes MacGregor, an Episcopalian priest who is Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the University of Southern California, Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, a recipient of the California Literature Award (Gold Medal, non-fiction category), and the first holder of the Rufus Jones Chair in Philosophy and Religion at Bryn Mawr, demonstrates in his book Reincarnation in Christianity: A New Vision of the Role of Rebirth in Christian Thought,[137] that Christian doctrine and reincarnation are not mutually exclusive belief systems.

New religious movements

Theosophy

The Theosophical Society draws much of its inspiration from India. The idea is, according to a recent Theosophical writer, "the master-key to modern problems," including heredity.[138] In the Theosophical world-view reincarnation is the vast rhythmic process by which the soul, the part of a person which belongs to the formless non-material and timeless worlds, unfolds its spiritual powers in the world and comes to know itself. It descends from sublime, free, spiritual realms and gathers experience through its effort to express itself in the world. Afterwards there is a withdrawal from the physical plane to successively higher levels of Reality, in death, a purification and assimilation of the past life. Having cast off all instruments of personal experience it stands again in its spiritual and formless nature, ready to begin its next rhythmic manifestation, every lifetime bringing it closer to complete self-knowledge and self-expression. However it may attract old mental, emotional, and energetic karma patterns to form the new personality.

Eckankar

Awareness of past lives, dreams, and soul travel are spiritual disciplines practiced by students of Eckankar. Eckankar teaches that each person is Soul, which transcends time and space. Soul travel is a term specific to Eckankar that refers to a shift in consciousness. Eckists believe the purpose of being aware of past lives is to help with understanding personal conditions in the present. Practicing students of Eckankar can become aware of past lives, through dreams, soul travel, and spiritual exercises called contemplations. This form of contemplation is the active, unconditional practice of going within to connect with the "Light and Sound of God" known as the divine life current or Holy Spirit.

Scientology

Past reincarnation, usually termed "past lives", is a key part of the principles and practices of the Church of Scientology. Scientologists believe that the human individual is actually an immortal thetan, or spiritual entity, that has fallen into a degraded state as a result of past-life experiences. Scientology auditing is intended to free the person of these past-life traumas and recover past-life memory, leading to a higher state of spiritual awareness. This idea is echoed in their highest fraternal religious order, the Sea Organization, whose motto is "Revenimus" or "We Come Back", and whose members sign a "billion-year contract" as a sign of commitment to that ideal. L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology, does not use the word "reincarnation" to describe its beliefs, noting that: "The common definition of reincarnation has been altered from its original meaning. The word has come to mean 'to be born again in different life forms' whereas its actual definition is 'to be born again into the flesh of another body.' Scientology ascribes to this latter, original definition of reincarnation."[139]

The first writings in Scientology regarding past lives date from around 1951 and slightly earlier. In 1960, Hubbard published a book on past lives entitled Have You Lived Before This Life. In 1968 he wrote Mission into Time, a report on a five-week sailing expedition to Sardinia, Sicily and Carthage to see if specific evidence could be found to substantiate L. Ron Hubbard's recall of incidents in his own past, centuries ago.

Meher Baba

The Indian spiritual teacher Meher Baba stated that reincarnation occurs due to desires and once those desires are extinguished the ego-mind ceases to reincarnate:

The power that keeps the individual soul bound to the wheel of life and death is its thirst for separate existence, which is a condition for a host of cravings connected with objects and experiences of the world of duality. It is for the fulfillment of cravings that the ego-mind keeps on incarnating itself. When all forms of craving disappear, the impressions which create and enliven the ego-mind disappear. With the disappearance of these impressions, the ego-mind itself is shed with the result that there is only the realisation of the one eternal, unchanging Oversoul or God, Who is the only reality. God-realisation is the end of the incarnations of the ego-mind because it is the end of its very existence. As long as the ego-mind exists in some form, there is an inevitable and irresistible urge for incarnations. When there is cessation of the ego-mind, there is cessation of incarnations in the final fulfillment of Self-realisation.[140]

See also

- Afterlife

- Bhavacakra

- Arthur Flowerdew

- Joan Grant

- Karmic astrology

- Life review

- Lifetimes True Accounts of Reincarnation

- Metempsychosis

- Past life regression

- Planes of existence

- Pre-existence

- Shanti Devi

- Soulmate

- Spiritism

- Subtle body

- Xenoglossy

- Zalmoxis

References

- ^ The Buddhist concept of rebirth is also often referred to as reincarnation.see Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper, Philip L. Quinn, A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. John Wiley and Sons, 2010, page 640, Google Books.

- ^ Gananath Obeyesekere, Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. University of California Press, 2002, page 15.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K (2007) [1924]. Origins of the Druze People and Religion, with Extracts from their Sacred Writings (New Edition). Columbia University Oriental Studies. 28. London: Saqi. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-86356-690-1

- ^ Heindel, Max (1985) [1939, 1908] The Rosicrucian Christianity Lectures (Collected Works): The Riddle of Life and Death. Oceanside, California. 4th edition. ISBN 0-911274-84-7

- ^ An important recent work discussing the mutual influence of ancient Greek and Indian philosophy regarding these matters is The Shape of Ancient Thought by Thomas McEvilley

- ^ a b c Template:PDFlink

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica". Concise.britannica.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Karl Sigmund. "Gödel Exhibition: Gödel's Century". Goedelexhibition.at. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ "Heart of Hinduism: Reincarnation and Samsara". Hinduism.iskcon.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Brodd, Jefferey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ Teachings of Queen Kunti by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Chapter 18 "To become Brahma is not a very easy thing.... But he is also a living entity like us."

- ^ "Reincarnation in Buddhism: What the Buddha Didn't Teach" By Barbara O'Brien, About.com

- ^ Transform Your Life: A Blissful Journey, pages 52-55), Tharpa Publications (2001, US ed. 2007) ISBN 978-0-9789067-4-0

- ^ "The Five Precepts". Urbandharma.org. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Mullasadra.org[dead link]

- ^ Says who ?

- ^ Diodorus Siculus thought the Druids might have been influenced by the teachings of Pythagoras. Diodorus Siculus v.28.6; Hippolytus Philosophumena i.25.

- ^ one modern scholar has speculated that Buddhist missionaries had been sent to Britain by the Indian king Ashoka. Donald A.Mackenzie, Buddhism in pre-Christian Britain (1928:21).

- ^ M. Dillon and N. Chadwick, The Celtic Realms, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, [page needed]

- ^ Ara, Mitra (2008). Eschatology in the Indo-Iranian traditions: The Genesis and Transformation of a Doctrine. Peter Lang Publishing Inc., New York, USA. ISBN 1-4331-0250-1. pp. 99-100.

- ^ Flood, Gavin. Olivelle, Patrick. 2003. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden: Blackwell. pg. 273-4. "The second half of the first millennium BCE was the period that created many of the ideological and institutional elements that characterize later Indian religions. The renouncer tradition played a central role during this formative period of Indian religious history....Some of the fundamental values and beliefs that we generally associate with Indian religions in general and Hinduism in particular were in part the creation of the renouncer tradition. These include the two pillars of Indian theologies: samsara - the belief that life in this world is one of suffering and subject to repeated deaths and births (rebirth); moksa/nirvana - the goal of human existence....."

- ^ Gavin D. Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press (1996), UK ISBN 0-521-43878-0 p. 86 - "A third alternative is that the origin of transmigration theory lies outside of vedic or sramana traditions in the tribal religions of the Ganges valley, or even in Dravidian traditions of south India."

- ^ Arvind Sharma's review of Hajime Nakamura's A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Jul., 1987), page 330.

- ^ T.U.Mehta,Path of Arhat - A Religious Democracy Pujya Sohanalala Smaraka Parsvantha Sodhapitha, 1993, Pages 7-8

- ^ R.D.Ranade. Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 108.

" But the culminating point of the whole doctrine is reached when the poet tells us that he himself saw (probably with his mind's eye) the guardian of the body, moving unerringly by backward and forward paths, clothed in collected and diffusive splendour, and that it kept on returning frequently inside the mundane regions. That this 'guardian' is no other than the soul may be seen from the way in which verse 31 follows immediately on verse 30 which mentions the 'breathing, speedful, moving life-principle'; moreover, the frequentative (varivarti) tells us the frequency of the soul's return to this world." (Interpretation of Rig Veda I.164.30-31)

- ^ P. 99 Religion and aging in the Indian tradition By Shrinivas Tilak

- ^ Provide reference(s) if this refers to rebirth?

- ^ "As is now almost universally accepted by informed Indological scholarship, a re-examination of early Buddhist historical material, ..., necessitates a redating of the Buddha's death to between 411 and 400 BCE." Paul Dundas, The Jains, 2nd edition, (Routledge, 2001), p. 24.

- ^ Karel Werner, The Longhaired Sage in The Yogi and the Mystic, Curzon Press, 1989, page 34. Wayman... traces them particularly in the older Upanishads, in early Buddhism, and in some later literature."

- ^ Paul Williams, Anthony Tribe, Buddhist thought: a complete introduction to the Indian tradition. Routledge, 2000, page 84.

- ^ Karel Werner, The Yogi and the Mystic. Routledge 1994, page 27.

- ^ Gavin D. Flood, The ascetic self: subjectivity, memory and tradition. Cambridge University Press, 2004, page 136.

- ^ Joanna Macy, Mutual causality in Buddhism and general systems theory: the dharma of natural systems. SUNY Press, 1991, page 163.

- ^ Schibli, S., Hermann, Pherekydes of Syros, p. 104, Oxford Univ. Press 2001

- ^ "The dates of his life cannot be fixed exactly, but assuming the approximate correctness of the statement of Aristoxenus (ap. Porph. V.P. 9) that he left Samos to escape the tyranny of Polycrates at the age of forty, we may put his birth round about 570 BCE, or a few years earlier. The length of his life was variously estimated in antiquity, but it is agreed that he lived to a fairly ripe old age, and most probably he died at about seventy-five or eighty." William Keith Chambers Guthrie, (1978), A history of Greek philosophy, Volume 1: The earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, page 173. Cambridge University Press

- ^ Linforth, Ivan M. (1941) The Arts of Orpheus Arno Press, New York, OCLC 514515

- ^ Long, Herbert S. (1948) A Study of the doctrine of metempsychosis in Greece, from Pythagoras to Plato (Long's 1942 Ph.D. dissertation) Princeton, New Jersey, OCLC 1472399

- ^ Long, Herbert S. (16 February 1948) "Plato's Doctrine of Metempsychosis and Its Source" The Classical Weekly 41(10): pp. 149—155

- ^ Menander, The Inspired Woman

- ^ Lucian, Gallus, 18 et seq.

- ^ Poesch, Jessie (1962) "Ennius and Basinio of Parma" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 25(1/2): pp. 116—118, page 117, FN15

- ^ Lucretius, (i. 124)

- ^ Horace, Epistles, II. i. 52

- ^ Virgil, The Aeneid, vv. 724 et seq.

- ^ The book Reincarnation in Christianity, by the theosophist Geddes MacGregor (1978) asserted that Origen believed in reincarnation. MacGregor is convinced that Origen believed in and taught about reincarnation but that his texts written about the subject have been destroyed. He admits that there is no extant proof for that position. The allegation was also repeated by Shirley MacLaine in her book Out On a Limb. Origen does discuss the concept of transmigration (metensomatosis) from Greek philosophy, but it is repeatedly stated that this concept is not a part of the Christian teaching or scripture in his Comment on the Gospel of Matthew (which survives only in a 6th-century Latin translatio): "In this place [when Jesus said Elijah was come and referred to John the Baptist] it does not appear to me that by Elijah the soul is spoken of, lest I fall into the doctrine of transmigration, which is foreign to the Church of God, and not handed down by the apostles, nor anywhere set forth in the scriptures" (13:1:46–53, see Commentary on Matthew, Book XIII

- ^ Much of this is documented in R.E. Slater's book Paradise Reconsidered.

- ^ Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010

- ^ Julius Caesar, "De Bello Gallico", VI

- ^ tr. Giles 1889, p. 304

- ^ "Newadvent.org". Newadvent.org. 1911-02-01. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Steven Runciman, The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy, 1982, isbn=0-521-28926-2, Cambridge University Press, The Bogomils, Google Books

- ^ For example Dondaine, Antoine. O.P. Un traite neo-manicheen du XIIIe siecle: Le Liber de duobus principiis, suivi d'un fragment de rituel Cathare (Rome: Institutum Historicum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 1939)

- ^ "Newadvent.org". Newadvent.org. 1907-03-01. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ "Bellow's translation of Helgakviða Hundingsbana II". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ "the souls must always be the same, for if none be destroyed they will not diminish in number." Republic X, 611. The Republic of Plato By Plato, Benjamin Jowett Edition: 3 Published by Clarendon press, 1888.

- ^ In a letter to his friend George Whatley written May 23, 1785: Jennifer T. Kennedy, Death Effects: Revisiting the conceit of Franklin's Memoir, Early American Literature, 2001. JSTOR

- ^ Marsilio Ficino, Platonic Theology, 17.3-4

- ^ "Again, Rosalind in "As You Like It" (Act III., Scene 2), says: I was never so be-rhimed that I can remember since Pythagoras's time, when I was an Irish rat" — alluding to the doctrine of the transmigration of souls." William H. Grattan Flood, quoted at Libraryireland.com

- ^ Boulting, 1914. pp. 163-64

- ^ a b Berger, Arthur S. (1991). The Encyclopedia of Parapsychology and Psychical Research. Paragon House Publishers. ISBN 1-55778-043-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schopenhauer, A: "Parerga und Paralipomena" (Eduard Grisebach edition), On Religion, Section 177

- ^ Nietzsche and the Doctrine of Metempsychosis, in J. Urpeth & J. Lippitt, Nietzsche and the Divine, Manchester: Clinamen, 2000

- ^ a b "Shirleymaclaine.com". Shirleymaclaine.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ David Hammerman, Lisa Lenard, The Complete Idiot's Guide to Reincarnation, Penguin, p.34. For relevant works by James, see; William James, Human Immortality: Two Supposed Objections to the Doctrine (the Ingersoll Lecture, 1897), The Will to Believe, Human Immortality (1956) Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-20291-7, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (1902), ISBN 0-14-039034-0, Essays in Radical Empiricism (1912) Dover Publications 2003, ISBN 0-486-43094-4

- ^ Richmal Crompton, More William, George Newnes, London, 1924, XIII. William and the Ancient Souls; "The memory usually came in a flash. For instance, you might remember in a flash when you were looking at a box of matches that you had been Guy Fawkes."

- ^ Théodore Flournoy, Des Indes à la planète Mars, Étude sur un cas de somnambulisme avec glossolalie, Éditions Alcan et Eggimann, Paris et Genève, 1900

- ^ Cadoret, Remi. Book Review: European Cases of the Reincarnation Type The American Journal of Psychiatry, April 2005.

- ^ Shroder, T (2007-02-11). "Ian Stevenson; Sought To Document Memories Of Past Lives in Children". The Washington Post.

- ^ Rockley, Richard. Book Review: Children who remember previous lives

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1996). Demon Haunted World. Random House. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-394-53512-8.

- ^ Shroder, Tom (2007-02-11). "Ian Stevenson; Sought To Document Memories Of Past Lives in Children". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Tony Walter and Helen Waterhouse, "A Very Private Belief: Reincarnation in Contemporary England". Sociology of Religion, Vol. 60, 1999

- ^ a b c "Popular psychology, belief in life after death and reincarnation in the Nordic countries, Western and Eastern Europe" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ China Regulates Buddhist Reincarnation[dead link]

- ^ Lynda Obst (2006). "Valentine to science - interview with Carl Sagan". Interview. p. 2. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ Jane Henry (2005). Parapsychology: research on exceptional experiences Routledge, p. 224.

- ^ Walter, T.; Waterhouse, H. (1999). "A very private belief: Reincarnation in contemporary England". Sociology of Religion. 60 (2): 187–197. doi:10.2307/3711748. JSTOR 3711748. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Waterhouse, H. (1999). "Reincarnation belief in Britain: New age orientation or mainstream option?". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 14 (1): 97–109. doi:10.1080/13537909908580854. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ Vivekjivandas, Sadhu. Hinduism: An Introduction - Part 1. (Swaminarayan Aksharpith: Ahmedabad, 2010) p. 33-36. ISBN 978-81-7526-433-5

- ^ "Bhagavad-Gita: Chapter 2, Verse 22". Bhagavad-Gita Trust. 1998–2009. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Jacobsen, Knut A. "Three Functions Of Hell In The Hindu Traditions." Numen 56.2-3 (2009): 385-400. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials. Web. 16 Sept. 2012.

- ^ Bhagavad Gita II.22, ISBN 1-56619-670-1

- ^ See Bhagavad Gita XVI.8-20

- ^ Rinehart, Robin, ed., Contemporary Hinduism19-21 (2004) ISBN 1-57607-905-8

- ^ Karel Werner, A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism 110 (Curzon Press 1994) ISBN 0-7007-0279-2

- ^ Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Translation by Swami Nikhilananda (8th Ed. 1992) ISBN 0-911206-01-9

- ^ Vivekjivandas, Sadhu. Hinduism: An Introduction - Part 1. (Swaminarayan Aksharpith: Ahmedabad, 2010) p. 46-47. ISBN 978-81-7526-433-5

- ^ Vivekjivandas, Sadhu. Hinduism: An Introduction - Part 1. (Swaminarayan Aksharpith: Ahmedabad, 2010) p. 47. ISBN 978-81-7526-433-5

- ^ "The sudden appearance of this theory [of karma] in a full-fledged form is likely to be due, as already pointed out, to an impact of the wandering muni-and-shramana-cult, coming down from the pre-Vedic non-Aryan time." Kashi Nsadcwath Upadhyaya, Early Buddhism and the Bhagavadgita. Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1998, page 76.

- ^ Kuhn, Hermann (2001) pp. 226–230

- ^ a b Krishan, Yuvraj (1997): p. 43.

- ^ Kuhn, Hermann (2001) pp.70–71

- ^ a b Kuhn, Hermann (2001) pp.64–66

- ^ Kuhn, Hermann (2001) p.15

- ^ Rankin, Aidan (2006) p.67

- ^ a b Jaini, Padmanabh (1998) p.108

- ^ The Jain hierarchy of life classifies living beings on the basis of the senses: five-sensed beings like humans and animals are at the top, and single sensed beings like microbes and plants are at the bottom.

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (1998) pp.108–09

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh (2000) p.130

- ^ Krishan, Yuvraj (1997) p.44

- ^ a b Kuhn, Hermann (2001) p.28

- ^ Kuhn, Hermann (2001) p.69

- ^ Kuhn, Hermann (2001) pp.65–66, 70–71

- ^ The many references in early Buddhist scriptures include; Mahakammavibhanga Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 136); Upali Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 56); Kukkuravatika Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 57); Moliyasivaka Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya 36.21); Sankha Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya 42.8). For an explicit rejection of this view in the early texts see David J. Kalupahana, Causality--the central philosophy of Buddhism. University Press of Hawaii, 1975, page 119.

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (London: Gordon Fraser Limited, 1990), p. 51

- ^ (M.1.256) "Post-Classical Developments in the Concepts of Karma and Rebirth in Theravada Buddhism." by Bruce Matthews. in Karma and Rebirth: Post-Classical Developments State Univ of New York Press: 1986 ISBN 0-87395-990-6 pg 125

- ^ Collins, Steven. Selfless persons: imagery and thought in Theravāda Buddhism Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-521-39726-X pg 215, Google Books

- ^ (D.3.105) "Post-Classical Developments in the Concepts of Karma and Rebirth in Theravada Buddhism. by Bruce Matthews. in Karma and Rebirth: Post-Classical Developments State Univ of New York Press: 1986 ISBN 0-87395-990-6 pg 125

- ^ Tucker, 2005, p.216

- ^ "PTS: Miln 71-72; 82-83; 84 (Pali Canon)". Accesstoinsight.org. 2010-06-30. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ His Holiness the Dalai Lama, How to Practice: The Way to a Meaningful Life (New York: Atria Books, 2002), p. 46

- ^ Bruce Matthews in Ronald Wesley Neufeldt, editor, Karma and Rebirth: Post Classical Developments. SUNY Press, 1986, page 125. Google.com

- ^ Rahula, p. 144

- ^ Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Accesstoinsight.org.

- ^ Peter Harvey, The Selfless Mind. Curzon Press 1995, page 247.

- ^ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 1, p. 377

- ^ The Connected Discourses of the Buddha. A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya, Bhikkhu Bodhi, Translator. Wisdom Publications

- ^ Transform Your Life: A Blissful Journey, page 52), Tharpa Publications (2001, US ed. 2007) ISBN 978-0-9789067-4-0

- ^ Reincarnation as understood by Sikh Religion[dead link]

- ^ Edwards, L. (2001). A Brief Guide to Beliefs: Ideas, Theologies, Mysteries, and Movements. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22259-5.

- ^ The Way of the Orisha by Philip John Neimark: Publisher HarperOne; 1st edition (May 28, 1993) ISBN 978-0-06-250557-6

- ^ Wilson, Peter Lamborn, Scandal: Essays in Islamic Heresy, Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia. (1988). ISBN 0-936756-13-6 hardcover 0-936756-12-2 paperback

- ^ Seabrook, W. B., Adventures in Arabia, Harrap and Sons 1928, (chapters on Druze religion)

- ^ Char Joog No Chanto - Seeking forgiveness for sins from past lives

- ^ Wasserman, James (2001). The Templars and the Assassins - The Militia of Heaven. Inner Traditions International. pp. 133–137. ISBN 0-89281-859-X.

- ^ see his To Die Before Death: The Sufi Way of Life

- ^ Gnostic liberation front The Sufi Message of Hazrat Inayat Khan

- ^ Reincarnation - Ask the Rabbi

- ^ Kabbalah for Dummies

- ^ Aish.com[dead link]

- ^ Sha'ar Ha'Gilgulim, The Gate of Reincarnations, Chaim Vital

- ^ Hare, John B. "Inuit Religion". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ Rink, Henry. "Tales and Traditions of the Eskimo". adapted by Weimer, Christopher, M. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ Jefferson, Warren (2008). Reincarnation beliefs of North American Indians : soul journeys, metamorphoses, and near-death experiences. Native Voices. ISBN 1-57067-212-1.

- ^ ANALYSIS December 9, 2009 (2009-12-09). "Pewforum.org". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Spiritual-wholeness.org". Spiritual-wholeness.org. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Cranston, Sylvia. "Reincarnation in Christianity: A New Vision of the Role of Rebirth in Christian Thought (Quest Books) (9780835605014): Geddes MacGregor: Books". Amazon.com. ASIN 0835605019.

{{cite web}}: Check|asin=value (help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Theosophy and reincarnation". Blavatskytrust.org.uk. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Does Scientology believe in reincarnation or past lives?

- ^ Baba, Meher, Discourses, Volume III, Sufism Reoriented, 1967, ISBN 1-880619-09-1, p. 96.

Further reading

- Alegretti, Wagner, Retrocognitions: An Investigation into Memories of Past Lives and the Period Between Lives. ISBN 0-9702131-6-6, 2004.

- Archiati, Pietro, Reincarnation in Modern Life: Toward a new Christian Awareness. ISBN 0-904693-88-0

- Atkinson, William Walker, Reincarnation and the Law of Karma: A Study of the Old-new World-doctrine of Rebirth and Spiritual Cause and Effect, Kessinger Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-7661-0079-0.

- Baba, Meher, Discourses, Sufism Reoriented, 1967, ISBN 1-880619-09-1.

- Faye, Louis Diène, "Mort et Naissance Le Monde Sereer", Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines (1983), ISBN 2-7236-0868-9

- Gravrand, Henry, "La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool", vol.2, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal, (1990) ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- Gravrand, Henry, "La civilisation sereer, Cosaan : les origines", vol. 1, Nouvelles Editions africaines (1983), ISBN 2-7236-0877-8

- Thiaw, Issa Laye, "La religiosité des Seereer, avant et pendant leur islamisation", in Éthiopiques, no. 54, volume 7, 2e semestre 1991

- Bache, Christopher M., Lifecycles, Reincarnation and the Web of Life, 1991, ISBN 1-55778-645-3

- Besant, A.W., Reincarnation, Published by Theosophical Pub. Society, 1892.

- Boulting, W. Giordano Bruno, His Life, Thought, and Martyrdom, London: Kegan Paul, 1914.

- Bowman, Carol, Children's Past Lives, 1998, ISBN 0-553-57485-X

- Bowman, Carol, Return from Heaven, 2003, ISBN 0-06-103044-9

- Cerminara, Gina, Many Mansions: The Edgar Cayce Story on Reincarnation, 1990, ISBN 0-451-03307-8

- Childs, Gilbert and Sylvia, Your Reincarnating Child: Welcoming a soul to the world. ISBN 1-85584-126-6

- Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (1980). Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03923-8.

- Doore, Gary, What Survives?, 1990, ISBN 0-87477-583-3

- Edwards, Paul, Reincarnation: A Critical Examination ISBN 1-57392-921-2

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Gyatso, Geshe Kelsang, Joyful Path of Good Fortune, pp 336–47, Tharpa Publications (2nd. ed., 1995) ISBN 978-0-948006-46-3

- Gyatso, Geshe Kelsang, Living Meaningfully, Dying Joyfully: The Profound Practice of Transference of Consciousness, Tharpa Publications (1999) ISBN 978-0-948006-63-0

- Head, Joseph and Cranston, S.L., editors, Reincarnation: The Phoenix Fire Mystery, 1994, ISBN 0-517-56101-8

- Jefferson, Warren. 2009. “Reincarnation Beliefs of North American Indians: Soul Journeys, Metamorphoses, and Near-Death Experiences.” Summertown, TN: Native Voices. ISBN 978-1-57067-212-5

- Heindel, Max, The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception (Part I, Chapter IV: Rebirth and the Law of Consequence), 1909, ISBN 0-911274-34-0

- Leland, Kurt. The Unanswered Question: Death, Near-Death, and the Afterlife. Hampton Roads Publishing (2002). ISBN 978-1-57174-299-5

- Klemp, H. (2003). Past lives, dreams, and soul travel. Minneapolis, MN: Eckankar. ISBN 1-57043-182-5