Mike Tyson

Mike Tyson | |

|---|---|

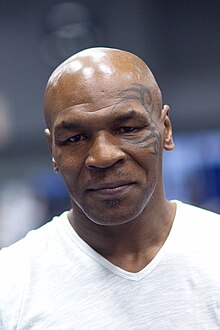

Tyson at SXSW 2011 | |

| Born | Michael Gerard Tyson June 30, 1966 Brooklyn, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Kid Dynamite[1] Iron Mike The Baddest Man on the Planet[2] |

| Statistics | |

| Weight(s) | Heavyweight |

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (178 cm) |

| Reach | 71 in (180 cm) |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 58 |

| Wins | 50 |

| Wins by KO | 44 |

| Losses | 6 |

| Draws | 0 |

| No contests | 2 |

Michael Gerard "Mike" Tyson (also known as Malik Abdul Aziz) (born June 30, 1966) is a retired American professional boxer. Tyson is a former undisputed heavyweight champion of the world and holds the record as the youngest boxer to win the WBC, WBA and IBF heavyweight titles at 20 years, 4 months, and 22 days old. Tyson won his first 19 professional bouts by knockout, 12 of them in the first round. He won the WBC title in 1986 after defeating Trevor Berbick by a TKO in the second round. In 1987, Tyson added the WBA and IBF titles after defeating James Smith and Tony Tucker. He was the first heavyweight boxer to simultaneously hold the WBA, WBC and IBF titles, and the only heavyweight to successively unify them.

In 1988, Tyson became the lineal champion when he knocked out Michael Spinks after 91 seconds. Tyson successfully defended the world heavyweight championship nine times, including victories over Larry Holmes and Frank Bruno. In 1990, he lost his titles to underdog James "Buster" Douglas, by a knockout in round 10. Attempting to regain the titles, he defeated Donovan Ruddock twice in 1991, but he pulled out of a fight with undisputed heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield due to injury. In 1992, Tyson was convicted of raping Desiree Washington and sentenced to six years in prison but was released after serving three years. After his release, he engaged in a series of comeback fights. In 1996, he won the WBC and WBA titles after defeating Frank Bruno and Bruce Seldon by knockout. After being stripped of the WBC title, Tyson lost his WBA crown to Evander Holyfield in November 1996 by an 11th round TKO. Their 1997 rematch ended when Tyson was disqualified for biting Holyfield's ear.

In 2002, he fought for the world heavyweight title at the age of 35, losing by knockout to Lennox Lewis. He retired from professional boxing in 2006, after being knocked out in consecutive matches against Danny Williams and Kevin McBride. Tyson declared bankruptcy in 2003, despite having received over US$30 million for several of his fights and $300 million during his career. Tyson was well known for his ferocious and intimidating boxing style as well as his controversial behavior inside and outside the ring. Tyson is considered one of the best heavyweights of all time.[3] He was ranked No. 16 on The Ring's list of 100 greatest punchers of all time.[4] and No. 1 in the ESPN.com list of "The hardest hitters in heavyweight history".[5] He has been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the World Boxing Hall of Fame.

Early years

Tyson was born in Brooklyn, New York City. He has a brother, Rodney, who is five years older than he. His sister, Denise, died of a heart attack at age 25 in 1991.[6] Tyson's father, Jimmy Kirkpatrick, abandoned his family when Tyson was 2, leaving his mother, Lorna Smith Tyson, to care for them on her own.[7] The family lived in Bedford-Stuyvesant until their financial burdens necessitated a move to Brownsville when Tyson was 10 years old.[8] Tyson's mother died six years later, leaving 16-year-old Tyson in the care of boxing manager and trainer Cus D'Amato, who would become his legal guardian. Tyson later said, "I never saw my mother happy with me and proud of me for doing something: She only knew me as being a wild kid running the streets, coming home with new clothes that she knew I didn't pay for. I never got a chance to talk to her or know about her. Professionally, it has no effect, but it's crushing emotionally and personally."[9]

Throughout his childhood, Tyson lived in and around high-crime neighborhoods. According to an interview in Details, his first fight was with a bigger youth who had pulled the head off one of Tyson's pigeons.[10] Tyson was repeatedly caught committing petty crimes and fighting those who ridiculed his high-pitched voice and lisp. By the age of 13, he had been arrested 38 times.[11] He ended up at the Tryon School for Boys in Johnstown, New York. Tyson's emerging boxing ability was discovered there by Bobby Stewart, a juvenile detention center counselor and former boxer.[7] Stewart considered Tyson to be an outstanding fighter and trained him for a few months before introducing him to Cus D'Amato.[7]

Tyson was later removed from the reform school by Cus D'Amato.[12] Kevin Rooney also trained Tyson, and he was occasionally assisted by Teddy Atlas, although he was dismissed by D'Amato when Tyson was 15. Rooney eventually took over all training duties for the young fighter.

Tyson's brother is a physician assistant in the trauma center of the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center.[13] He has always been very supportive of his brother's career and was often seen at Tyson's boxing matches in Las Vegas, Nevada. When asked about their relationship, Mike has been quoted saying, "My brother and I see each other occasionally and we love each other," and "My brother was always something and I was nothing."[14]

Education

Mike Tyson dropped out of high school as a junior and never graduated. In 1989, along with Don King, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from Central State University, in Wilberforce, Ohio by university President Arthur E. Thomas.[15][16]

Career

Amateur career

Tyson won gold medals at the 1981 and 1982 Junior Olympic Games, defeating Joe Cortez in 1981 and beating Kelton Brown in 1982. Brown's corner threw in the towel in the first round. He holds the Junior Olympic record for quickest knockout (8 seconds). He won every bout at the Junior Olympic Games by knockout.

He fought Henry Tillman twice as an amateur, losing both bouts by close decision. Tillman went on to win heavyweight gold at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Rise to stardom

Tyson made his professional debut as an 18-year-old on March 6, 1985, in Albany, New York. He defeated Hector Mercedes via a first round knockout.[7] He had 15 bouts in his first year as a professional. Fighting frequently, Tyson won 26 of his first 28 fights by KO or TKO; 16 of those came in the first round.[17] The quality of his opponents gradually increased to journeyman fighters and borderline contenders,[17] like James Tillis, David Jaco, Jesse Ferguson, Mitch Green and Marvis Frazier. His win streak attracted media attention and Tyson was billed as the next great heavyweight champion. D'Amato died in November 1985, relatively early into Tyson's professional career; some speculate that his death was the genesis of many of the troubles Tyson was to experience as his life and career progressed.[18]

Tyson's first nationally televised bout took place on February 16, 1986, at Houston Field House in Troy, New York against journeyman heavyweight Jesse Ferguson. Tyson knocked down Ferguson with an uppercut in the fifth round that broke Ferguson's nose.[19] During the sixth round, Ferguson began to hold and clinch Tyson in an apparent attempt to avoid further punishment. After admonishing Ferguson several times to obey his commands to box, the referee finally stopped the fight near the middle of the sixth round. The fight was initially ruled a win for Tyson by disqualification (DQ) of his opponent. The ruling was "adjusted" to a win by technical knockout (TKO) after Tyson's corner protested that a DQ win would end Tyson's string of knockout victories, and that a knockout would have been the inevitable result. The rationale offered for the revised outcome was that the fight was actually stopped because Ferguson could not (rather than would not) continue boxing.

On November 22, 1986, Tyson was given his first title fight against Trevor Berbick for the World Boxing Council (WBC) heavyweight championship. Tyson won the title by second round TKO, and at the age of 20 years and 4 months became the youngest heavyweight champion in history.[20] Tyson's dominant performance brought many accolades. Donald Saunders wrote: "The noble and manly art of boxing can at least cease worrying about its immediate future, now [that] it has discovered a heavyweight champion fit to stand alongside Dempsey, Tunney, Louis, Marciano and Ali."[21]

Because of Tyson's strength, many fighters were intimidated by him.[22] This was backed up by his outstanding hand speed, accuracy, coordination, power, and timing. Tyson was also noted for his defensive abilities.[23] Holding his hands high in the Peek-a-Boo style taught by his mentor Cus D'Amato, he slipped and weaved out of the way of the opponent's punches while closing the distance to deliver his own punches.[23] One of Tyson's trademark combinations was a right hook to his opponent's body followed by a right uppercut to his opponent's chin; very few boxers would remain standing if caught by this combination. Jesse Ferguson and Jose Ribalta were among the boxers knocked down by the combination.

Undisputed champion

Expectations for Tyson were extremely high, and he embarked on an ambitious campaign to fight all of the top heavyweights in the world. Tyson defended his title against James Smith on March 7, 1987, in Las Vegas, Nevada. He won by unanimous decision and added Smith's World Boxing Association (WBA) title to his existing belt.[24] 'Tyson mania' in the media was becoming rampant.[25] He beat Pinklon Thomas in May with a knockout in the sixth round.[26] On August 1 he took the International Boxing Federation (IBF) title from Tony Tucker in a twelve round unanimous decision.[27] He became the first heavyweight to own all three major belts – WBA, WBC, and IBF – at the same time. Another fight, in October of that year, ended with a victory for Tyson over 1984 Olympic super heavyweight gold medalist Tyrell Biggs by knockout in the seventh round.[28]

During this time, Tyson came to the attention of gaming company Nintendo. After witnessing one of Tyson's fights, Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa was impressed by the fighter's "power and skill", prompting him to suggest Tyson be included in the upcoming Nintendo Entertainment System port of the Punch Out!! arcade game. In 1987, Nintendo released Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!!, which was well received and sold more than a million copies.[29]

Tyson had three fights in 1988. He faced Larry Holmes on January 22, 1988, and defeated the legendary former champion by a fourth round KO.[30] This was the only knockout loss Holmes suffered in 75 professional bouts. In March, Tyson then fought contender Tony Tubbs in Tokyo, Japan, fitting in an easy two-round victory amid promotional and marketing work.[31]

On June 27, 1988, Tyson faced Michael Spinks. Spinks, who had taken the heavyweight championship from Larry Holmes via a 15-round decision in 1985, had not lost his title in the ring but was not recognized as champion by the major boxing organizations. Holmes had previously given up all but the IBF title, and that was eventually stripped from Spinks after he elected to fight Gerry Cooney (winning by a 5th-round TKO) rather than IBF Number 1 Contender Tony Tucker, as the Cooney fight provided him a larger purse. However, Spinks did become the lineal champion by beating Holmes and many (including Ring magazine) considered him to have a legitimate claim to being the true heavyweight champion. The bout was, at the time, the richest fight in history and expectations were very high. Boxing pundits were predicting a titanic battle of styles, with Tyson's aggressive infighting conflicting with Spinks' skillful out-boxing and footwork. The fight ended after 91 seconds when Tyson knocked Spinks out in the first round; many consider this to be the pinnacle of Tyson's fame and boxing ability.[32][33] Spinks, previously unbeaten, would never fight professionally again.

Controversy and upset

During this period, Tyson's problems outside boxing were also starting to emerge. His marriage to Robin Givens was heading for divorce,[34] and his future contract was being fought over by Don King and Bill Cayton.[35] In late 1988, Tyson parted with manager Bill Cayton and fired longtime trainer Kevin Rooney, the man many credit for honing Tyson's craft after the death of D'Amato.[23][36][37][38] Following Rooney's departure, critics alleged that Tyson began to stop working the body, relying less on the jab to get inside, clinching more, using the Peek-a-Boo style sporadically and throwing few combinations.[39] Tyson insisted he hadn't altered the style that made him a world champion.[40] In 1989, Tyson had only two fights amid personal turmoil. He faced the popular British boxer Frank Bruno in February. Bruno managed to stun Tyson at the end of the 1st round,[41] although Tyson went on to knock out Bruno in the fifth round. Tyson then knocked out Carl "The Truth" Williams in one round in July.[42]

By 1990, Tyson seemed to have lost direction, and his personal life and training habits were in disarray. In a fight on February 11, 1990, he lost the undisputed championship to Buster Douglas in Tokyo.[43] Tyson was a huge betting favorite, but Douglas (priced at 42/1) was at an emotional peak after losing his mother to a stroke 23 days prior to the fight; Douglas fought the fight of his life.[43] Contrary to reports that Tyson was out of shape, sources noted his pronounced muscles, absence of body fat and weight of 220 and 1/2 pounds, only 2 pounds more than he had weighed when he beat Michael Spinks 20 months earlier.[44][45][46] Mentally, however, Tyson was unprepared. Tyson failed to find a way past Douglas's quick jab that had a 12-inch (30 cm) reach advantage over his own.[47] Tyson did send Douglas to the floor in the eighth round, catching him with an uppercut, but Douglas recovered sufficiently to hand Tyson a heavy beating in the subsequent two rounds. (After the fight, the Tyson camp would complain that the count was slow and that Douglas had taken longer than ten seconds to get to his feet.)[48] Just 35 seconds into the 10th round, Douglas unleashed a brutal combination of hooks that sent Tyson to the canvas for the first time in his career. He was counted out by referee Octavio Meyran.[43]

The knockout victory by Douglas over Tyson, the previously undefeated "baddest man on the planet" and arguably the most feared boxer in professional boxing at that time, has been described as one of the most shocking upsets in modern sports history.[49]

After Douglas

After the loss, Tyson recovered with first-round knockouts of Henry Tillman[50] and Alex Stewart[51] in his next two fights. Tyson's victory over Tillman, the 1984 Olympic heavyweight gold medalist, enabled Tyson to avenge his amateur losses at Tillman's hands. These bouts set up an elimination match for another shot at the undisputed world heavyweight championship, which Evander Holyfield had taken from Douglas in his first defense of the title.

Tyson, who was the number one contender, faced number two contender Donovan "Razor" Ruddock on March 18, 1991, in Las Vegas. Ruddock was seen as the most dangerous heavyweight around and was thought of as one of the hardest punching heavyweights. Tyson and Ruddock went back and forth for most of the fight, until referee Richard Steele controversially stopped the fight during the seventh round in favor of Tyson. This decision infuriated the fans in attendance, sparking a post-fight melee in the audience. The referee had to be escorted from the ring.[52]

Tyson and Ruddock met again on June 28 that year, with Tyson knocking down Ruddock twice and winning a 12 round unanimous decision.[53] A fight between Tyson and Holyfield for the undisputed championship was arranged for the autumn of 1991. The match between Tyson and reigning champion Holyfield was scheduled for November 8, 1991 at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, but Tyson pulled out after sustaining a rib cartilage injury during training.

Rape conviction, prison, and conversion

Tyson was arrested in July 1991 for the rape of 18-year-old Desiree Washington, Miss Black Rhode Island, in an Indianapolis hotel room. Tyson's rape trial took place in the Indianapolis courthouse from January 26 to February 10, 1992.

Desiree Washington testified that she received a phone call from Tyson at 1:36 am on July 19, 1991 inviting her to a party. Having joined Tyson in his limousine, Washington testified that Tyson made sexual advances towards her. She testified that upon arriving at his hotel room, Tyson pinned her down on his bed and raped her despite her pleas to stop. She ran out of the room and asked Tyson's chauffeur to drive her back to her hotel.[citation needed] Partial corroboration of Washington's story came via testimony from Tyson's chauffeur, Virginia Foster, who confirmed Desiree Washington's state of shock. Further testimony came from Thomas Richardson, the emergency room physician who examined Washington more than 24 hours after the incident and confirmed that Washington's physical condition was consistent with rape.[54]

Under lead defense lawyer Vincent Fuller's direct examination, Tyson claimed that everything had taken place with Washington's full cooperation and he claimed not to have forced himself upon her. When he was cross-examined by lead prosecutor Gregory Garrison, Tyson denied claims that he had misled Washington and insisted that she wanted to have sex with him. Because of Tyson's hostile and defensive responses to the questions during cross-examination, some have speculated that his behavior made him unlikable to the jury who saw him as brutish and arrogant.[55] Tyson was convicted on the rape charge on February 10, 1992 after the jury deliberated for nearly 10 hours.[56]

Alan Dershowitz filed an appeal on Tyson's behalf alleging that the victim had a history of at least one false accusation of rape[57] and that the judge had blocked testimony from witnesses who would have contradicted Washington. The Indiana Court of Appeals ruled against Tyson in a 2–1 vote.[58]

On March 26, he was sentenced to six years in prison followed by four years on probation.[59] He was assigned to the Indiana Youth Center (now the Plainfield Correctional Facility) in April 1992,[60] and he was released in March 1995 after serving three years.[61] During his incarceration, Tyson converted to Islam.[62]

Comeback

After being paroled from prison, Tyson easily won his comeback bouts against Peter McNeeley and Buster Mathis Jr.. Tyson's first comeback fight grossed more than US$96 million worldwide, including a United States record $63 million for PPV television. The fight was purchased by 1.52 million homes, setting both PPV viewership and revenue records.[63] The 89-second fight elicited criticism that Tyson's management lined up "tomato cans" to ensure easy victories for his return.[64] TV Guide included the Tyson-McNeeley fight in their list of the 50 Greatest TV Sports Moments of All Time in 1998.[65]

Tyson regained one belt by easily winning the WBC title from Frank Bruno in March 1996. It was the second fight between the two, and Tyson knocked Bruno out in the third round.[66] Tyson added the WBA belt by defeating champion Bruce Seldon in one round in September that year. Seldon was severely criticized and mocked in the popular press for seemingly collapsing to innocuous punches from Tyson.[67]

Tyson–Holyfield fights

Tyson vs. Holyfield I

Tyson attempted to defend the WBA title against Evander Holyfield, who was in the fourth fight of his own comeback. Holyfield had retired in 1994 following the loss of his championship to Michael Moorer. It was said that Don King and others saw former champion Holyfield, who was 34 at the time of the fight and a huge underdog, as a washed-up fighter.[68]

On November 9, 1996, in Las Vegas, Nevada, Tyson faced Holyfield in a title bout dubbed "Finally." In a surprising turn of events, Holyfield, who was given virtually no chance to win by numerous commentators,[69] defeated Tyson by TKO when referee Mitch Halpern stopped the bout in round 11.[70] Holyfield became the second person to win a heavyweight championship belt three times. Holyfield's victory was marred by allegations from Tyson's camp of Holyfield's frequent headbutts[71] during the bout. Although the headbutts were ruled accidental by the referee,[71] they would become a point of contention in the subsequent rematch.[72]

Tyson vs. Holyfield II and aftermath

Tyson and Holyfield fought again on June 28, 1997. Originally, Halpern was supposed to be the referee, but after Tyson's camp protested, Halpern stepped aside in favor of Mills Lane.[73] The highly anticipated rematch was dubbed The Sound and the Fury, and it was held at the Las Vegas MGM Grand Garden Arena, site of the first bout. It was a lucrative event, drawing even more attention than the first bout and grossing $100 million. Tyson received $30 million and Holyfield $35 million, the highest paid professional boxing purses until 2007.[74][75] The fight was purchased by 1.99 million households, setting a pay-per-view buy rate record that stood until the May 5, 2007, De La Hoya-Mayweather boxing match.[75][76]

Soon to become one of the most controversial events in modern sports,[77] the fight was stopped at the end of the third round, with Tyson disqualified[78] for biting Holyfield on both ears. The first time Tyson bit him, the match was temporarily stopped. Referee Mills Lane deducted two points from Tyson and the fight resumed. However, after the match resumed, Tyson did it again; Tyson was disqualified and Holyfield won the match. One bite was severe enough to remove a piece of Holyfield's right ear, which was found on the ring floor after the fight.[79] Tyson later stated that his actions were retaliation for Holyfield repeatedly headbutting him without penalty.[72] In the confusion that followed the ending of the bout and announcement of the decision, a near riot erupted in the arena and several people were injured.[80]

Tyson's former trainer, Teddy Atlas, had predicted that Tyson would be disqualified. "He planned this," Atlas said. "That's the only reason he went through with this fight. This was a charade so he could get out and live with himself as long as in his world he would be known as savage and brutal. In his world, he was the man who attacked like an animal and people would say he was trying to annihilate Holyfield, trying to kill him, when nothing could be further from the truth."[81]

As a subsequent fallout from the incident, US$3 million was immediately withheld from Tyson's $30-million purse by the Nevada state boxing commission (the most it could legally hold back at the time).[82] Two days after the fight, Tyson issued a statement,[83] apologizing to Holyfield for his actions and asked not to be banned for life over the incident.[84] Tyson was roundly condemned in the news media but was not without defenders. Novelist and commentator Katherine Dunn wrote a column that criticized Holyfield's sportsmanship in the controversial bout and charged the news media with being biased against Tyson.[85]

On July 9, 1997, Tyson's boxing license was rescinded by the Nevada State Athletic Commission in a unanimous voice vote; he was also fined US$3 million and ordered to pay the legal costs of the hearing.[86] As most state athletic commissions honor sanctions imposed by other states, this effectively made Tyson unable to box in the United States. The revocation was not permanent, as the commission voted 4–1 to restore Tyson's boxing license on October 18, 1998.[87]

During his time away from boxing in 1998, Tyson made a guest appearance at WrestleMania XIV as an enforcer for the main event match between Shawn Michaels and Steve Austin. During this time, Tyson was also an unofficial member of D-Generation X. Tyson was paid $3 million for being guest enforcer of the match at WrestleMania XIV.[88]

1999 to 2005

After Holyfield

In January 1999, Tyson returned to the ring to fight the South African Francois Botha, in another fight that ended in controversy. While Botha initially controlled the fight, Tyson allegedly attempted to break Botha's arms during a tie-up and both boxers were cautioned by the referee in the ill-tempered bout. Botha was ahead on points on all scorecards and was confident enough to mock Tyson as the fight continued. Nonetheless, Tyson landed a straight right-hand in the fifth round that knocked out Botha.[89] Critics noticed Tyson stopped using the bob and weave defence altogether following this return.[90]

Legal problems caught up with Tyson once again. On February 5, 1999, Tyson was sentenced to a year's imprisonment, fined $5,000, and ordered to serve two years probation and perform 200 hours of community service for assaulting two motorists after a traffic accident on August 31, 1998.[91] He served nine months of that sentence. After his release, he fought Orlin Norris on October 23, 1999. Tyson knocked down Norris with a left hook thrown after the bell sounded to end the first round. Norris injured his knee when he went down and said he was unable to continue the fight. Consequently, the bout was ruled a no contest.[92]

"I'm the best ever. I'm the most brutal and vicious, the most ruthless champion there has ever been. No one can stop me. Lennox is a conqueror? No! I'm Alexander! He's no Alexander! I'm the best ever. There’s never been anyone as ruthless as me. I'm Sonny Liston. I'm Jack Dempsey. There's no one like me. I'm from their cloth. There is no one who can match me. My style is impetuous, my defense is impregnable, and I'm just ferocious. I want his heart! I want to eat his children! Praise be to Allah!"

Tyson's post fight interview after knocking out Lou Savarese 38 seconds into the bout in June 2000.[93]

In 2000, Tyson had three fights. The first was staged at the MEN Arena, Manchester, England against Julius Francis. Following controversy as to whether Tyson should be allowed into the country, he took four minutes to knock out Francis, ending the bout in the second round.[94] He also fought Lou Savarese in June 2000 in Glasgow, winning in the first round; the fight lasted only 38 seconds. Tyson continued punching after the referee had stopped the fight, knocking the referee to the floor as he tried to separate the boxers.[95] In October, Tyson fought the similarly controversial Andrzej Gołota,[96] winning in round three after Gołota was unable to continue due to a broken jaw. The result was later changed to no contest after Tyson refused to take a pre-fight drug test and then tested positive for marijuana in a post-fight urine test.[97] Tyson fought only once in 2001, beating Brian Nielsen in Copenhagen with a seventh round TKO.[98]

Lewis vs. Tyson

Tyson once again had the opportunity to fight for a heavyweight championship in 2002. Lennox Lewis held the WBC, IBF, IBO and Lineal titles at the time. As promising amateurs, Tyson and Lewis had sparred at a training camp in a meeting arranged by Cus D'Amato in 1984.[99] Tyson sought to fight Lewis in Nevada for a more lucrative box-office venue, but the Nevada Boxing Commission refused him a license to box as he was facing possible sexual assault charges at the time.[100]

Two years prior to the bout, Tyson had made several inflammatory remarks to Lewis in an interview following the Savarese fight. The remarks included the statement "I want your heart, I want to eat your children."[101] On January 22, 2002, the two boxers and their entourages were involved in a brawl at a New York press conference to publicize the planned event.[102] The melee put to rest any chance of a Nevada fight, but alternative arrangements were made. The fight eventually occurred on June 8 at the Pyramid Arena in Memphis, Tennessee. Lewis dominated the fight and knocked out Tyson with a right hook in the eighth round. Tyson was respectful after the fight and praised Lewis on his victory.[103] This fight was the highest-grossing event in pay-per-view history at that time, generating $106.9 million from 1.95 million buys in the USA.[75][76]

Late career, bankruptcy and retirement

In another Memphis fight on February 22, 2003, Tyson beat fringe contender Clifford Etienne 49 seconds into round one. The pre-fight was marred by rumors of Tyson's lack of fitness. It was said that he took time out from training to party in Las Vegas and get a new facial tattoo.[104] This would be Tyson's final professional victory in the ring.

In August 2003, after years of financial struggles, Tyson finally filed for bankruptcy.[105][106] In 2003, amid all his economic troubles, he was named by Ring Magazine at number 16, right behind Sonny Liston, among the 100 greatest punchers of all time.

On August 13, 2003, Tyson entered the ring for a face-to-face confrontation against K-1 fighting phenom Bob Sapp immediately after Sapp's win against Kimo Leopoldo in Las Vegas. K-1 signed Tyson to a contract with the hopes of making a fight happen between the two, but Tyson's felony history made it impossible for him to obtain a visa to enter Japan, where the fight would have been most profitable. Alternate locations were discussed, but the fight never came to fruition.[107] It is unknown if he actually profited from this arrangement.

On July 30, 2004, Tyson faced British boxer Danny Williams in another comeback fight, this time staged in Louisville, Kentucky. Tyson dominated the opening two rounds. The third round was even, with Williams getting in some clean blows and also a few illegal ones, for which he was penalized. In the fourth round, Tyson was unexpectedly knocked out. After the fight, it was revealed that Tyson was trying to fight on one leg, having torn a ligament in his other knee in the first round. This was Tyson's fifth career defeat.[108] He underwent surgery for the ligament four days after the fight. His manager, Shelly Finkel, claimed that Tyson was unable to throw meaningful right-hand punches since he had an elbow injury.[109]

On June 11, 2005, Tyson stunned the boxing world by quitting before the start of the seventh round in a close bout against journeyman Kevin McBride. After losing the third of his last four fights, Tyson said he would quit boxing because he felt he had lost his passion.[110]

Exhibition tour

To help pay off his debts, Tyson returned to the ring in 2006 for a series of four-round exhibitions against journeyman heavyweight Corey "T-Rex" Sanders in Youngstown, Ohio.[111] Tyson, without headgear at 5 ft 10.5 in and 216 pounds, was in great shape, but far from his prime against Sanders, with headgear at 6 ft 8 in and 293 pounds, a loser of his last seven pro bouts and nearly blind from a detached retina in his left eye. Tyson appeared to be "holding back" in these exhibitions to prevent an early end to the "show". "If I don't get out of this financial quagmire there's a possibility I may have to be a punching bag for somebody. The money I make isn't going to help my bills from a tremendous standpoint, but I'm going to feel better about myself. I'm not going to be depressed," explained Tyson about the reasons for his "comeback".[112]

Legacy

A 1998 ranking of "The Greatest Heavyweights of All-Time" by Ring magazine placed Tyson at No.14 on the list.[113] Despite criticism of facing underwhelming competition during his unbeaten run as champion, Tyson's knockout power and intimidation factor made him the sport's most dynamic box office attraction.[114] Many believe Tyson was the last great heavyweight champion.[115]

In Ring Magazine's list of the 80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years, released in 2002, Tyson was ranked at No. 72.[116] He is ranked No. 16 on Ring Magazine's 2003 list of 100 greatest punchers of all time.[117]

On June 12, 2011, Tyson was inducted to the International Boxing Hall of Fame alongside legendary Mexican champion Julio César Chávez, light welterweight champion Kostya Tszyu, and actor/screenwriter Sylvester Stallone.[118]

After professional boxing

On the front page of USA Today on June 3, 2005, Tyson was quoted as saying: "My whole life has been a waste – I've been a failure." He continued: "I just want to escape. I'm really embarrassed with myself and my life. I want to be a missionary. I think I could do that while keeping my dignity without letting people know they chased me out of the country. I want to get this part of my life over as soon as possible. In this country nothing good is going to come of me. People put me so high; I wanted to tear that image down."[119] Tyson began to spend much of his time tending to his 350 pigeons in Paradise Valley, an upscale enclave near Phoenix, Arizona.[120]

Tyson has stayed in the limelight by promoting various websites and companies.[121] In the past Tyson had shunned endorsements, accusing other athletes of putting on a false front to obtain them.[122] Tyson has held entertainment boxing shows at a casino in Las Vegas[123] and started a tour of exhibition bouts to pay off his numerous debts.[124]

On December 29, 2006, Tyson was arrested in Scottsdale, Arizona, on suspicion of DUI and felony drug possession; he nearly crashed into a police SUV shortly after leaving a nightclub. According to a police probable-cause statement, filed in Maricopa County Superior Court, "[Tyson] admitted to using [drugs] today and stated he is an addict and has a problem."[125] Tyson pleaded not guilty on January 22, 2007 in Maricopa County Superior Court to felony drug possession and paraphernalia possession counts and two misdemeanor counts of driving under the influence of drugs. On February 8 he checked himself into an inpatient treatment program for "various addictions" while awaiting trial on the drug charges.[126]

On September 24, 2007, Mike Tyson pleaded guilty to possession of cocaine and driving under the influence. He was convicted of these charges in November 2007 and sentenced to 24 hours in jail, 360 hours community service and 3 years probation. Prosecutors had requested a year-long jail sentence, but the judge praised Tyson for seeking help with his drug problems.[127] On November 11, 2009, Mike Tyson was arrested after getting into a scuffle at Los Angeles International airport with a photographer.[128] No charges were filed.

Tyson appeared in the 2009 film The Hangover as a caricature of himself and has continued to appear in the WWE.

In September 2011, Tyson gave an interview in which he made comments about former Alaska governor Sarah Palin that included crude and violent descriptions of interracial sex. These comments were then reprinted on the Daily Caller website. Journalist Greta van Susteren criticized Tyson and the Daily Caller over the comments, which she described as "smut" and "violence against women".[129]

In April 2012, Tyson gave an interview in which he made comments about the Trayvon Martin case, telling Yahoo News that "It's a disgrace George Zimmerman hasn't been dragged out of his house and tied to a car and taken away. That's the only kind of retribution that people like that understand. It's a disgrace that man hasn't been shot yet. Forget about him being arrested—the fact that he hasn't been shot yet is a disgrace. That's how I feel personally about it."[130]

Tyson started in his own one-man show on Broadway in August 2012.[131][132]

In October 2012, Tyson launched the Mike Tyson Cares Foundation.[133] The mission of the Mike Tyson Cares Foundation is to “give kids a fighting chance” by providing innovative centers that provide for the comprehensive needs of kids from broken homes. Tyson will guest star in a 2013 episode of the long-running NBC legal drama, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit as a murderous death row inmate. Andre Braugher portraying his defense counsel.[134]

Personal life

Tyson has been legally married three times and has eight children with several different women.

His first marriage was to actress Robin Givens from February 7, 1988 to February 14, 1989.[34] Givens was known for her work on the sitcom Head of the Class. Tyson's marriage to Givens was especially tumultuous, with allegations of violence, spousal abuse and mental instability on Tyson's part.[135] Matters came to a head when Tyson and Givens gave a joint interview with Barbara Walters on the ABC TV newsmagazine show 20/20 in September 1988, in which Givens described life with Tyson as "torture, pure hell, worse than anything I could possibly imagine."[136] Givens also described Tyson as "manic depressive" on national television while Tyson looked on with an intent and calm expression.[135] A month later, Givens announced that she was seeking a divorce from the allegedly abusive Tyson.[135] They had no children but she claims to have had a miscarriage; Tyson claims she was never pregnant and only used that to get him to marry her.[135][137] During their marriage, the couple lived in a mansion in Bernardsville, New Jersey.[138][139]

His second marriage was to Monica Turner from April 19, 1997 to January 14, 2003.[140] At the time of the divorce filing, Turner worked as a pediatric resident at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington DC.[141] She is the sister of Michael Steele, the former Lieutenant Governor of Maryland and former Republican National Committee Chairman.[142] Turner filed for divorce from Tyson in January 2002, claiming that he committed adultery during their five-year marriage, an act that "has neither been forgiven nor condoned."[141] The couple had two children, Rayna and Amir.

On May 25, 2009, Tyson's 4-year-old daughter Exodus was found by her 7-year-old brother Miguel, unconscious and tangled in a cord, dangling from an exercise treadmill. The child's mother untangled her, administered CPR and called for medical attention. Exodus was listed in "extremely critical condition" and was on life support at St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix. She died of her injuries on May 26, 2009.[143][144]

Eleven days after his daughter's death, Tyson wed for the third time, to long-time girlfriend Lakiha "Kiki" Spicer, age 32, exchanging vows on Saturday, June 6, 2009, in a short, private ceremony at the La Bella Wedding Chapel at the Las Vegas Hilton.[145] Spicer was a resident of nearby suburban Henderson, Nevada. County marriage records in Las Vegas show the couple got a marriage license 30 minutes before their ceremony. Spicer is the mother of Tyson's daughter Milan and son Morocco. His other children include Mikey (born 1990), Miguel (born 2002) and D'Amato (born 1990). He has a total of eight children including the deceased Exodus.

Tyson has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder.[146] While on the American talk show The View in early May 2010, Tyson revealed that he is now forced to live paycheck to paycheck.[147] He went on to say: "I'm totally destitute and broke. But I have an awesome life, I have an awesome wife who cares about me. I'm totally broke. I had a lot of fun. It (losing his money) just happened. I'm very grateful. I don't deserve to have the wife that I have; I don't deserve the kids that I have, but I do, and I'm very grateful."

In March 2011, Tyson appeared on The Ellen DeGeneres Show to discuss his new Animal Planet reality series, Taking on Tyson. In the interview with DeGeneres, Tyson discussed some of the ways he had improved his life in the past two years, including sober living and a vegan diet.[148]

Popular culture

At the height of his fame and career in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Tyson was one of the most recognized sports personalities in the world. Apart from his many sporting accomplishments, his outrageous and controversial behavior in the ring and in his private life has kept him in the public eye and in the courtroom.[149] As such, Tyson has appeared in myriad popular media in cameo appearances in film and television. He has also been featured in video games and as a subject of parody or satire.

Published in 2007, author Joe Layden's book The Last Great Fight: The Extraordinary Tale of Two Men and How One Fight Changed Their Lives Forever, chronicled the lives of Tyson and Douglas before and after their heavyweight championship fight. The book received positive reviews and claimed the fight was essentially the beginning of the end of boxing's popularity in mainstream sports.

In 2008, the documentary Tyson premiered at the annual Cannes Film Festival in France. The film was directed by James Toback and has interviews with Tyson and clips of his fights and from his personal life. It received high critical praise, scoring an 86% approval rating on the website Rotten Tomatoes from a pool of over 100 film critics.

Professional boxing record

Boxing championships and accomplishments

Tyson established an impressive list of accomplishments, mostly early in his career:[151]

Titles

- Junior Olympic Games Champion Heavyweight 1982

- National Golden Gloves Champion Heavyweight 1984

- Undisputed Heavyweight champion (held all three major championship belts; WBA, IBF, and WBC) – August 1, 1987 – February 11, 1990

- WBC Heavyweight Champion – November 22, 1986 – February 11, 1990, March 16, 1996 – September 24, 1996 (Vacated)

- WBA Heavyweight Champion – March 7, 1987 – February 11, 1990, September 7, 1996 – November 9, 1996

- IBF Heavyweight Champion – August 1, 1987 – February 11, 1990

Records

- Youngest Heavyweight champion – 20 years and 4 months

- Junior Olympic quickest KO – 8 seconds

Awards

- Ring Magazine Fighter of the Year—1986 & 1988

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year Overseas Personality—1989

- Ring magazine Prospect of the Year—1985

Professional Wrestling

- WWE Hall Of Fame (Class Of 2012) [152]

References

- ^ SI article on Mike Tyson. Sportsillustrated.cnn.com (September 9, 1991). Retrieved on 2011-11-25.

- ^ Boyd, Todd (2008). African Americans and Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 235. ISBN 9780313064081. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Eisele, Andrew (2007). "50 Greatest Boxers of All-Time". About.com. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Eisele, Andrew (2003). "Ring Magazine's 100 Greatest Punchers". About.com. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Houston, Graham (2007). "The hardest hitters in heavyweight history". ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (May 21, 2002). "Boxing: Tyson Remains an Object of Fascination". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Puma, Mike., Sportscenter Biography: 'Iron Mike' explosive in and out of ring, ESPN.com, 2005-10-10. Retrieved March 27, 2007

- ^ "Mike Tyson Biography". BookRags.

- ^ Mike Tyson Quotes. Kjkolb.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-25.

- ^ "Mike Tyson Interview, Details Magazine".

- ^ Mike Tyson, St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture via findarticles.com. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Roberts & Skutt (1999), The Boxing Register:Cus D'Amato, via International Boxing Hall of Fame, McBooks Press.. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (May 21, 2002). "Tyson Remains An Object of Fascination". The New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ Berkow, Ira., Tyson Remains An Object of Fascination, The New York Times, 2002-05-21. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing. 1989. p. 28.

- ^ "SPORTS PEOPLE: BOXING; A Doctorate for Tyson". The New York Times. April 25, 1989. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "Iron" Mike Tyson, Cyberboxingzone.com Boxing record. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ Hornfinger, Cus D'Amato, SaddoBoxing.com. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Oates, Joyce C., Mike Tyson, Life Magazine via author's website, November 22, 1986. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Pinnington, Samuel., Trevor Berbick – The Soldier of the Cross, Britishboxing.net, January 31, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Graham Houston. "Which fights will Tyson be remembered for?". ESPN. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ Para, Murali., "Iron" Mike Tyson – His Place in History[dead link], Eastsideboxing.com, September 25. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c Richmann What If Mike Tyson And Kevin Rooney Reunited?, Saddoboxing.com, February 24, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), "Tyson Unifies W.B.C.-W.B.A. Titles", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 5, Page 1, Column 4, March 8, 1987.

- ^ Bamonte, Bryan., Bad man rising[dead link]. The Daily Iowan, 2005-10-06. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), "Tyson Retains Title On Knockout In Sixth", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 5, Page 1, Column 2, May 31, 1987.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), "Boxing — Tyson Undisputed And Unanimous Titlist", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 1, Page 51, Column 1, August 2, 1987.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1987), "Tyson Retains Title In 7 Rounds", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 1, Page 51, Column 1, October 17, 1987.

- ^ "Profile: Minoru Arakawa". N-Sider. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1988), "Tyson Keeps Title With 3 Knockdowns in Fourth," The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section 1, Page 47, Column 5, January 23, 1988.

- ^ Shapiro, Michael. (1988), "Tubbs's Challenge Was Brief and Sad", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section A, Page 29, Column 1, March 22, 1988.

- ^ Berger, Phil. (1988), "Tyson Knocks Out Spinks at 1:31 of Round 1", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section B, Page 7, Column 5, June 28, 1988.

- ^ Simmons, Bill (June 11, 2002). "Say 'goodbye' to our little friend". ESPN. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ a b SPORTS PEOPLE: BOXING; Tyson and Givens: Divorce Is Official, AP via New York Times, 1989-06-02. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ SPORTS PEOPLE: BOXING; King Accuses Cayton, New York Times, 1989-01-20. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Dettloff, William (December 20, 2010). "Great fighters make great trainers, not the other way around". The Ring. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ Too late to save Tyson – boxing – ESPN. Sports.espn.go.com (2002). Retrieved on 2012-06-19.

- ^ Woods, Michael (August 1, 2012). "Rooney Jr. hangs up the gloves". ESPN. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ Hoffer, Richard (June 24, 1991). "Where's The Fire?". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ Berger, Phil (November 20, 1991). "BOXING; Whatever It Takes, Holyfield Delivers". NY Times. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Bruno vs Tyson, BBC TV. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1989), "Tyson Stuns Williams With Knockout in 1:33," The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition-Final, Section 1, Page 45, Column 2, July 22, 1989.

- ^ a b c Kincade, Kevin., "The Moments": Mike Tyson vs Buster Douglas, Eastsideboxing.com, 2005-07-12. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Reilly, Rick (April 18, 2012). "Tyson: I just liked morphine". ESPN. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ Schaap, Jeremy. "Busting the myths of Tyson-Douglas". ESPN.

- ^ Graham, Bryan (February 11, 2010). "One writer's ultimate prediction". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ Phil, Berger (February 13, 1990). "Tyson Failed to Make Adjustments". NY Times. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Bellfield, Lee., Buster Douglas – Mike Tyson 1990, Saddoboxing.com, 2006-02-16. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Staff, Page 2's List for top upset in sports history, ESPN.com, May 23, 2001. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1990), "TYSON WINS IN 1st ROUND", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition-Final, Section 8, Page 7, Column 4, June 17, 1990.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1990), "BOXING; Tyson Scores Round 1 Victory", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition-Final, Section 8, Page 1, Column 5, December 9, 1990.

- ^ Bellfield, Lee., March 1991-Mike Tyson vs. Razor Ruddock, Saddoboxing.com, March 13, 2005. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (1991), "Tyson Floors Ruddock Twice and Wins Rematch", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition-Final, Section 1, Page 29, Column 5, June 29, 1991.

- ^ Peter Heller (August 21, 1995). Bad Intentions: The Mike Tyson Story. Da Capo Press. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-0-306-80669-8. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ Great American Trials; The Mike Tyson Trial, 1992; ISBN 1-57859-199-6; Copyright 1994; New England Publishing Associates Inc.

- ^ Muscatine, Alison., Tyson Found Guilty of Rape, Two Other Charges, The Washington Post via MIT-The Tech, February 11, 1992. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ "Mike Tyson's attorneys claim Desiree Washington cried rape previously". Jet. 1993.

- ^ "Indiana court upholds Tyson rape conviction – Mike Tyson". Jet. 1993.

- ^ Shipp, E. R. (March 27, 1992). "Tyson Gets 6-Year Prison Term For Rape Conviction in Indiana". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Mike Tyson Assigned To Indiana Youth Center." Orlando Sentinel. April 16, 1992. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (1995), "BOXING; After Three Years in Prison, Tyson Gains His Freedom", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition – Final, Section 8, Page 1, Column 2, March 26, 1995.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (November 13, 1994). "The Tyson, Olajuwon Connection". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ SPORTS PEOPLE: BOXING; Record Numbers for Fight, AP via New York Times, 2005-09-01. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (1995), "TV SPORTS; Who Must Tyson Face Next? A Finer Brand of Tomato Can", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late Edition – Final, Section B, Page 8, Column 1, August 22, 1995.

- ^ "50 Greatest TV Sports Moments of All Time", TV Guide, July 11, 1998

- ^ Bellfield, Lee., March 1996 – Frank Bruno vs. Mike Tyson II, Saddoboxing.com, 2005-03-18. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Gordon, Randy., Tyson-Seldon 1–1–1–1–1, Cyberboxingzone.com, 1996-09-04. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Cohen, Andrew., Evander Holyfield: God Helps Those Who Help Themselves[dead link], What is Enlightenment Magazine, Issue No. 15, 1999. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ Shetty, Sanjeev., Holyfield makes history, BBC Sports, 2001-12-26. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ^ Katsilometes, John., Holyfield knocks fight out of Tyson, Las Vegas Review-Journal, 1996-11-10. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Tyson camp objects to Halpern as referee, AP via Canoe.ca, 1997-06-26. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Tyson: 'I'd bite again', BBC Sports, 1999-10-04. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ Lane late replacement, center of action, AP via Slam! Boxing, June 29, 1997. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Holyfield vs. Tyson – 'fight of the times', AP via Slam! Boxing, 1997-06-25. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c Dahlberg, Tim. De La Hoya-Mayweather becomes richest fight in boxing history, AP via International Herald Tribune, May 9, 2007. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ^ a b Umstead, R. Thomas (February 26, 2007). "De La Hoya Bout Could Set a PPV Record". Multichannel News. Variety Group. Retrieved March 25, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ ESPN25: Sports Biggest Controversies, ESPN.com. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Tyson DQd for biting Holyfield, AP via Slam! Boxing, 1997-06-29. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Buffery, Steve., Champ chomped by crazed Tyson, The Toronto Sun via Slam! Boxing, June 29, 1997. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Dozens injured in mayhem following bout, AP via Slam! Boxing, June 29, 1997. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ "Atlas Shrugged, He Knows What's Eating Tyson", Michael Katz, New York Daily News, June 30, 1997

- ^ Buffery, Steve., Officials may withhold Tyson's money, The Toronto Sun via Slam! Boxing, 1997-06-29. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ The text of Mike Tyson's statement, AP via Slam! Boxing, July 30, 1997. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Tyson: "I am sorry", AP via Slam! Boxing, July 30, 1997. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Dunn, Katherine. DEFENDING TYSON, PDXS via cyberboxingzone.com, July 9, 1997. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ Tyson banned for life, AP via Slam! Boxing, July 9, 1997. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ Mike Tyson timeline, ESPN, January 29, 2002. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Biography for Mike Tyson at IMDb

- ^ Rusty Tyson finds the perfect punch, BBC News, January 17, 1999. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ [1], "CNN" June 1, 2002, Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- ^ Tyson jailed over road rage, BBC News, February 6, 1999. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Feour, Royce., No-contest; more trouble, Las Vegas Review-Journal, October 24, 1999. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Mike Tyson. YouTube (February 4, 2006). Retrieved on 2011-11-25.

- ^ Tyson wastes little time, BBC Sport, 2000-01-30. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ Tyson fight ends in farce, BBC Sport, June 25, 2000. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ Gregg, John., Iron Mike Makes Golota Quit[dead link], BoxingTimes.com, October 20, 2000. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. (2001), "PLUS: BOXING; Tyson Tests Positive For Marijuana", The New York Times, Sports Desk, Late City Final Edition, Section D, Page 5, Column 4, January 19, 2001.

- ^ Brutal Tyson wins in seven, BBC Sport, October 14, 2001. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ Rafael, Dan., Lewis vs. Tyson: The prequel, USA Today, June 3, 2002. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Mike Tyson rap sheet, CBC.ca, January 12, 2007. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ York, Anthony., "I want to eat your children, ..., Salon.com, 2000-06-28. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ AP, Tyson media circus takes center stage, ESPN.com, January 22, 2002. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ Lewis stuns Tyson for famous win, BBC Sport, June 9, 2002. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ Etienne's night ends 49 seconds into first round, AP via ESPN.com, February 22, 2003. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Tyson files for bankruptcy, BBC Sport, August 3, 2002. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ In re Michael G. Tyson, Chapter 11 petition, Aug. 1, 2003, case no. 03-41900-alg, U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York.

- ^ K-1 Reports Official Mike Tyson Fight. Tysontalk.com (April 15, 2004). Retrieved on 2011-11-25.

- ^ Williams shocks Tyson, BBC Sports, 2004-07-31. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Tyson camp blames injury, BBC Sports, 2004-07-31. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Tyson quits boxing after defeat, BBC Sport, 2005-06-12. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ "Mike Tyson World Tour: Mike Tyson versus Corey Sanders pictures". Tyson Talk.

- ^ Rozenberg, Sammy. "Tyson Happy With Exhibition, Fans Are Not". Boxing Scene. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ The Editors of Ring Magazine. (1999). The 1999 Boxing Alamanac and Book of Facts. Ft. Washington, PA: London Publishing Co. p. 132. ISSN 10849410.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check|issn=value (help) - ^ Campbell, Brian (June 8, 2011). "Taking a true measure of Tyson's legacy". ESPN. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ Quenqua, Douglas (March 14, 2012). "The Fight Club Generation". New York Times. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ "Ring Magazine's 80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years". Boxing.about.com. April 9, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Ring Magazine's 100 Greatest Punchers". Boxing.about.com. April 9, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Boxers Chavez, Tszyu and Tyson Elected to Int'l Boxing Hall of Fame –. Ibhof.com (December 7, 2010). Retrieved on 2011-11-25.

- ^ Saraceno, Jon., Tyson: 'My whole life has been a waste', USAToday.com, 2005-06-02. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Tyson has flown coop in new home, AP via MSNBC.com, 2005-06-22. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Henderson, Kenneth., A Look at Mike Tyson's Life after Boxing[dead link], ringsidereport.com, 2002-06-20. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ Saraceno, Jon., Tyson shows good-guy side with kids, USA Today, 2002-06-06. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ Birch, Paul., Tyson reduced to Vegas turn, BBC Sports, 2002-09-13. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ Debt-ridden Tyson returns to ring, BBC Sports, 2006-09-29. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ Gaynor, Tim., Mike Tyson arrested on cocaine charges[dead link], Reuters via Yahoo.com, 2007-12-30. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Khan, Chris., Boxing: Tyson enters rehab facility, AP via The Albuquerque Tribune, 2007-02-08. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ^ BBC NEWS, Tyson Jailed on Drugs Charges, news.bbc.com, 2007-11-19. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ Joyce Eng. "Mike Tyson Arrested in Airport Scuffle". TVGuide.com.

- ^ "Greta Van Susteren: Tucker Carlson's a 'pig' for Palin story".

- ^ "Mike Tyson on George Zimmerman: 'It's a disgrace he hasn't been shot yet'". Yahoo! News. April 12, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Weiner, Jonah (August 30, 2012). "Mike Tyson speaks out". Rolling Stone Magazine. p. 28.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Scheck, Frank (August 2, 2012). "Mike Tyson:Undisputed Truth:Theater Review". Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ {{|title=Mike Tyson Cares Foundation |url=http://www.miketysoncares.org |}}

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (January 10, 2013). "Mike Tyson To Play Convicted Murderer On 'Law & Order: SVU'". Deadline. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Ebony (1989). "Mike Tyson vs. Robin Givens: the champ's biggest fight". Find Articles at BNet. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ Wife Discusses Tyson, AP via New York Times, 1988-09-30. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ Berger, Phil (October 26, 1988). "Boxing Notebook; Lalonde-Leonard: It's Same Old Hype". The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ^ Gross, Ken. "As Wife Robin Givens Splits for the Coast, Mike Tyson Rearranges the Furniture", People, October 17, 1988. Retrieved March 21, 2011. "The food lies untouched. The only sounds across the breakfast table in the Bernardsville, N.J., mansion are the loud silences of words being swallowed.Finally, Robin Givens, 24, star of the ABC-TV sitcom Head of the Class, pushes herself away from the table and announces, 'I have to pack.' 'Me, too,' says her husband, Mike Tyson, 22, the world heavyweight boxing champion. Suddenly the Sunday morning atmosphere is tense and full of menace."

- ^ via Associated Press. Mike Tyson Chronology, USA Today, June 12, 2005. Retrieved March 21, 2011. "Oct. 2, 1988 – Police go to Tyson's Bernardsville, N.J., home after he hurls furniture out the window and forces Givens and her mother to flee the house."

- ^ Jet (2003). "Tyson finalizes divorce, could pay ex $9 million". Find Articles at BNet. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ a b The Smoking Gun: Archive, The Smoking Gun. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff; Lorber, Janie. "Profile of Michael Steele". The New York Times.

- ^ "Police: Tyson's daughter on life support". CNN. May 26, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Tyson's daughter dies after accident, police say". CNN. May 27, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Mike Tyson Marries Two Weeks After Daughter's Death". TVGuide.com. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ Schaap, Jeremy (September 13, 2006). "Who is the new Mike Tyson?". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Mike Tyson – Tyson: 'I'm Totally Broke'. Contactmusic.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-25.

- ^ "Mike Tyson Talks Sobriety and Vegan Life with Ellen DeGeneres". UrbLife.com. March 8, 2011.

- ^ ESPN25: The 25 Most Outrageous Characters, ESPN25.com. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ "Mike Tyson Professional boxing record". BoxRec.com.

- ^ "Press Office - Sports Personality Of The Year: overseas winners key facts". BBC. January 1, 1970. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "WWE Hall of Fame 2012 - Mike Tyson induction: photos". WWE.com. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Boxing record for Mike Tyson from BoxRec (registration required)

- Mike Tyson's Amateur Boxing Record

- Mike Tyson at IMDb

- Joyce Carol Oates on Mike Tyson, 1986–1997

- June 2005 SI Tyson Retrospective Photo Gallery

- Profile at Online World of Wrestling

- "The Suburbanization of Mike Tyson," New York Times Magazine, March 15, 2011

- Mike Tyson. Title Fight Stats – Reference book

- Mike Tyson Film Takes a Swing at His Old Image by Tim Arango, The New York Times, May 11, 2008

- 1966 births

- African-American boxers

- African-American Muslims

- American male professional wrestlers

- American people convicted of assault

- American rapists

- American sportspeople in doping cases

- American vegans

- Boxers from New York

- Converts to Islam from Christianity

- Converts to Sufism

- D-Generation X members

- African-American professional wrestlers

- Doping cases in boxing

- International Boxing Federation champions

- International Boxing Hall of Fame inductees

- Living people

- National Golden Gloves champions

- People convicted of drug offenses

- People convicted of rape

- People from Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn

- People from Bernardsville, New Jersey

- People with bipolar disorder

- Vegan sportspeople

- World Boxing Association champions

- World Boxing Council champions

- World heavyweight boxing champions

- WWE Hall of Fame